The “Wrestling Renaissance” Wasn’t About to be Derailed by the Revelation That One of its Superstars Battered Women — One of Them to Her Death

In 1992 the Village Voice commissioned me to supplement my Jockbeat items about the WWF drug and sex scandals with a lengthy cover story. The article never ran, for complicated reasons, and I later won a court judgment against the Voice for payment of my full fee. Though the half-edited and obsolete main article doesn’t stand the test of time for inclusion in this volume, I present here the infamous and equally unpublished “sidebar.”

For Vince McMahon, the Hundred Million Dollar Man, Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka made for a challenging tag-team partner. The World Wrestling Federation’s second-most-popular star in the early eighties, Snuka was an illiterate immigrant from Fiji prone to bouts with the law that threatened the revocation of his green card, and a drug abuser who often missed bookings. During a Middle East tour in the summer of 1985, fellow wrestlers say, customs officials in Kuwait caught him with controlled substances taped to his body, and he was allowed to leave the country only after some fancy footwork.

But Snuka’s near–Midnight Express experience in the Persian Gulf was child’s play compared to what happened on May 10, 1983. That night, after finishing his last match at the WWF TV taping at the Lehigh County Agricultural Hall in Allentown, Pennsylvania, he returned to Room 427 of the George Washington Motor Lodge in nearby Whitehall to find his girlfriend of nearly a year, Nancy Argentino, gasping for air. Two hours later, this twenty-three-year-old wrestling fan — who’d worked as a dentist’s assistant in Brooklyn and dropped out of Brooklyn Community College to travel with Snuka — was pronounced dead at Allentown Sacred Heart Medical Center of “undetermined craniocerebral injuries.”

“Upon viewing the body and speaking to the pathologist, I immediately suspected foul play, and so notified the district attorney,” Lehigh County coroner Wayne Snyder told me on a recent trip to Allentown. In ’83 Snyder was deputy to coroner Robert Weir. Yet no charges were filed in the case, no coroner’s inquest was held, and no evidence was presented to a grand jury.

Officially the case is still open — meaning Argentino’s death was never ruled either an accident or a homicide — though the original two-month-long investigation has been inactive for nine years. Under Pennsylvania’s unusually broad exemptions from freedom of information laws, the Whitehall Township Police Department so far has refused my requests for access to the file.

Of particular interest would be two documents: the autopsy and the transcript of the interrogation of Snuka immediately thereafter. One local official involved in the investigation, as well as one of the Argentino family’s lawyers, told me the autopsy showed marks on the victim other than the fractured skull. And former Whitehall police supervisor of detectives Al Fitzinger remembered that the forensic pathologist, Dr. Isadore Mihalakis, confronted Snuka to ask him why he’d waited so long before calling an ambulance. Gerald Procanyn, the current supervisor of detectives who worked on the case nine years ago, maintained that Snuka cooperated fully with investigators after being informed of his right to have a lawyer present, and was accompanied only by McMahon.

Another investigator, however, saw things differently; he said Snuka invoked his naïve jungle-boy wrestler’s gimmick as a way of playing dumb. “I’ve seen that trick before,” the investigator said. “He was letting McMahon act as his mouthpiece.”

Another curious circumstance was the presence at the interrogation of William Platt, the county district attorney. According to experts, chief prosecutors rarely interview suspects, especially in early stages of investigations, for the obvious reason that they may become witnesses and hence have to recuse themselves from handling the subsequent trials.

Detective Procanyn gave me the following summary of Snuka’s story. On the afternoon before she died, Snuka and his girlfriend were driving his purple Lincoln Continental from Connecticut to Allentown for the WWF taping. They’d been drinking, and they stopped by the side of the road — the spot was never determined, but perhaps it was near the intersection of Routes 22 and 33 — to relieve their bladders. In the process, Argentino slipped on mossy ground near a guard rail and struck the back of her head. Thinking nothing of it, she proceeded to drive the car the rest of the way to the motel (Snuka didn’t have a driver’s license) and, after they checked in, picked up take-out food at the nearby City View Diner. Snuka had no idea she was in any kind of distress until he returned late that night from the matches at the Agricultural Hall.

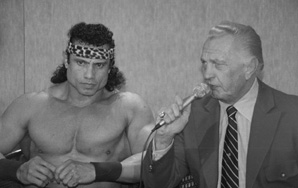

Jimmy Snuka and “manager” Buddy Rogers interviewed for a WWF TV taping

Procanyn said Snuka’s story never wavered, and no contradictory evidence was found.

Curiously, contemporary news coverage, such as the front-page account in the Allentown Morning Call, made no mention of a scenario of peeing by the roadside. It focused, instead, on the question of whether Argentino fell or was pushed in the motel room. Nine years later, the reporter, Tim Blangger, vividly recalled that at one point in his interview of Procanyn the detective grabbed him by the shoulders in a speculative reenactment of how Snuka might have shoved the woman more strongly than he intended.

Procacyn also claimed to have no knowledge of any subsequent action by the Argentino family, except for a few communications between a lawyer and D.A. Platt over settling the funeral bill. In fact, the Argentinos commissioned two separate private investigations, and it’s difficult to believe that Procanyn was unaware of them. The first investigator, New York lawyer Richard Cushing, traveled to Allentown, conducted extensive interviews, and aggressively demanded access to medical records and other files.

“It was a very peculiar situation,” Cushing told me. “I came away feeling Snuka should have been indicted. The police and the D.A. felt otherwise. The D.A. seemed like a nice enough person who wanted to do nothing. There was fear, I think, on two counts: fear of the amount of money the World Wrestling Federation had, and physical fear of the size of these people.”

Even so, Cushing declined to represent the family in a wrongful-death civil suit against Snuka. The lawyer cited the fact that Snuka and Argentino weren’t married, that they didn’t have children, and that she wasn’t working, which would make it difficult to establish loss of consortium. “Moreover, Vince McMahon made it clear to me that her reputation would be besmirched. As a lawyer, I had to determine if a contingency [fee] was in order; my business decision, not my moral judgment, was no. The family wasn’t pleased. They had a typical working-class family’s anger that justice wasn’t done.”

Through the generosity of Nancy Argentino’s father’s boss, the family then retained a Park Avenue law firm. The report filed by its private investigator shows that Snuka was as creative outside the ring as he was inside it:

• To the Whitehall police officer who responded to the first emergency call, Snuka said “he and Nancy were fooling around outside the motel room door when he inadvertently pushed Nancy and she fell, striking her head.”

• An emergency room nurse heard him state that “they were very tired and they got into an argument resulting in an accidental pushing incident. Ms. Argentino fell back and hit her head.”

• In the official police interrogation, Snuka first floated the peed-on-the-roadside theory.

• Finally, in a meeting with the hospital chaplain, he said he and Argentino had been stopped by the side of the road and had a lovers’ quarrel: “He accidentally shoved Ms. Argentino, who then fell backwards hitting her head on the pavement. They then arrived at the motel and went to bed. The next morning, Ms. Argentino complained that she was ill and stayed in bed. . . . When he came home from the taping, he observed that Ms. Argentino was clearly in bad shape.”

In 1985 the Argentinos obtained a $500,000 default judgment against Snuka in United States District Court in Philadelphia. The family never collected a dime; Snuka’s lawyers withdrew from the case, stating that they hadn’t been paid, and Snuka filed an affidavit claiming he was broke and unemployed and owed the IRS $75,000 in back taxes.

Since 1983, the forty-nine-year-old Snuka has been in and out of rehab centers and has wrestled off and on both in Japan and throughout this country. His original WWF stint extended two and a half years beyond Argentino’s death; his most recent ended earlier this year. According to the wrestling grapevine, he’s now trying to promote independent shows in, of all places, Salt Lake City, but my efforts to track him down there were unsuccessful.

Proving negligence, of course, is different from proving involuntary manslaughter or murder. But critics of the criminal investigation question the failure of the police to examine seriously Snuka’s history of drug abuse and violence against women.

Former wrestling great Buddy Rogers, who’d been hired by McMahon to serve as Snuka’s TV “manager” and get him to important matches on time, said he stopped driving with the Superfly after he brazenly snorted coke when they were in the car together. “Jimmy could be a sweet person, but on that stuff he was totally uncontrollable,” said Rogers, who was also Snuka’s neighbor on Coles Mill Road in Haddonfield, New Jersey. Snuka’s wife, with whom he had four children, befriended Rogers’ wife. “Jimmy used to beat the shit out of that woman,” Rogers said. “She would show up at our house, bruised and battered. But she couldn’t leave him — he had her hooked on the same junk he was using.”

Nancy Argentino’s younger sister remembered once being threatened by Snuka when they were alone at the family’s home in Flatbush. “I could kick you and put my hands around your throat and nobody would know,” he allegedly said. After Nancy’s death, family members said, they received a series of phone calls from a woman who identified herself as a former Snuka girl-friend who’d tried to warn Nancy away from him. Snuka, said the woman, had once broken her ribs, and had a thing about pushing women back against walls.

Finally, there was the incident involving Snuka and Argentino at a Howard Johnson’s in Salina, New York, outside Syracuse, just three months before Allentown. The motel owner, hearing noise from their room, called the police, who found Snuka and Argentino running naked down the hallway. It took eight deputy sheriffs and a police dog to subdue Snuka. Argentino sustained a bruise of her right thumb. Snuka pleaded guilty to violent felony assault with intent to cause injury, received a conditional discharge on counts of third-degree assault, harassment, and obstruction of a government official, and donated $1,500 to a deputy sheriffs’ survivors’ fund. Whitehall police later decided this was all the result of “a nervous desk clerk,” Detective Procanyn told me.

According to attorney Cushing, McMahon made a remark at one point in their discussions that was at once insightful and chilling.

“Look, I’m in the garbage business,” the promoter said. “If you think I’m going to be hurt by the revelation that one of my wrestlers is really a violent individual, you’re mistaken.”

Six months after Nancy Argentino died, the Village Voice ran a prescient article entitled “Mat Madness,” by the late columnist Arthur Bell, weather vane of the lower-Manhattan gay-arts demimonde. After attending a Madison Square Garden show head-lined by a bout between Superfly Snuka and The Magnificent Muraco, Bell — who knew next to nothing about wrestling — commented on the spectacle’s graphic references to bodily functions, and on its barely sublimated undercurrents of sexual dominance and sadomasochism.

“Take my word,” Bell declared with the confidence of a culture-monger paid to deliver big opinions, “by the end of 1984, wrestling will be the most popular sport in New York since mugging.”

Bell concluded with a vignette at the Garden stage exit, where a swarm of fans, led by a woman named Bea from West Orange, converged to taunt the wrestlers as they emerged in their street clothes.

Snuka throttles ECW founder Tod Gordon

“Hey, Superfly,” Bea shouted to Snuka. “You goddam fuckin’ murderer. When are you gonna kill another girl?”

Superfly Snuka, in his sixties, is still kicking around. In his most recent WWE stint (more recent than the one referenced in the above article from 1992) they even made a big deal out of his talking openly about past problems with substance abuse (the same ploy that would be used to help get Eddie Guerrero “over” just a year or so before Guerrero was found dead in a hotel room). But, needless to add, not even on this dose of “reality television” did Snuka or anyone else ever breathe a word about Nancy Argentino.

William H. Platt, district attorney of Lehigh County from 1976 to 1991, went on to become city solicitor of Allentown, and is now president judge of the County Court of Common Pleas.

Sgt. Slaughter wants you!