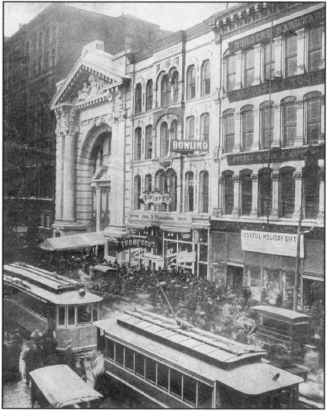

Main entrance of the Iroquois shortly after the fire broke out. Trolleys and other vehicles are stopped in Randolph Street but there is no sign of fire apparatus. (Author’s Collection)

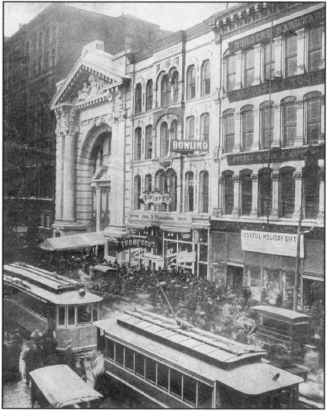

Intersection of Randolph and Dearborn Streets showing theater entrance to the right of the Delaware Building, the rear of the theatre to its left and the Northwestern building across Couch Place alley. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

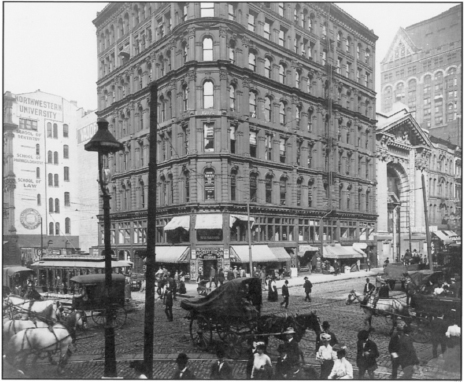

The Iroquois opening night souvenir booklet. (Billy Rose Theater Collection, New York City Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center)

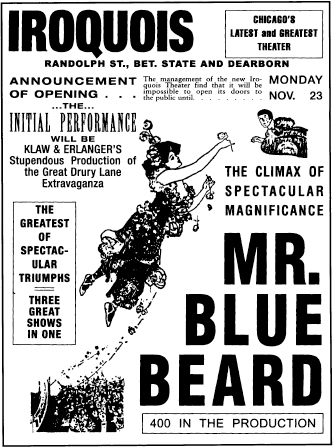

A full-page Chicago Tribune advertisement for the show, showing the ballet girl “floating above the heads of the audience.” (Author’s Collection)

Newspaper cartoon of Foy appearing in “drag” with the Pony Ballet girls in “The Old Woman Who Lived in the Shoe” routine from Mr. Bluebeard. (Collection of Armond Fields)

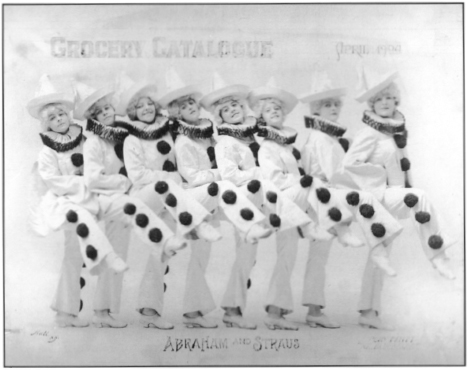

The Pony Ballet. (Billy Rose Collection)

Nellie Reed, star of the aerial ballet, lost her life in the fire. (Author’s Collection)

Bonnie Maginn, Bluebeard’s lead dancer. (Author’s Collection)

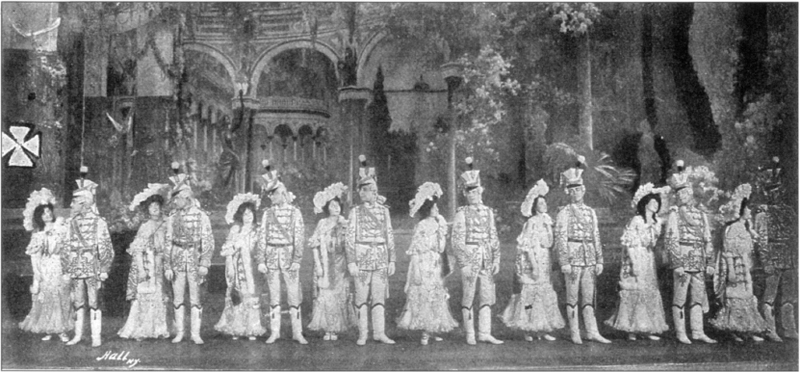

The scene onstage when the fire started [the X to the left marks the position of the faulty spotlight]. The actors continued to perform the double octet as burning fabric fluttered down. (Author’s Collection)

Carter H. Harrison, Mayor of Chicago, hurriedly returned from out of state when he learned of the disaster. (Author’s Collection)

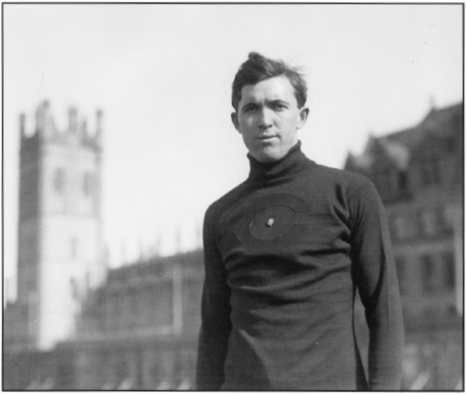

Clyde Blair, Captain of the University of Chicago Track Team, escaped from the theatre with his friends. Other students were not as lucky. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

Eddie Foy, the star of Mr. Bluebeard who tried to calm the audience, became an international hero overnight. (Collection of Armond Fields)

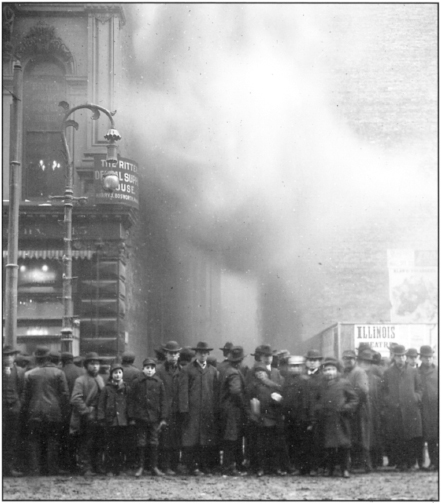

Smoke obscures the planks spanning Couch Place from the Northwestern building (left) to the theatre (right). At least 125 people jumped or fell to their deaths on the cobblestones below. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

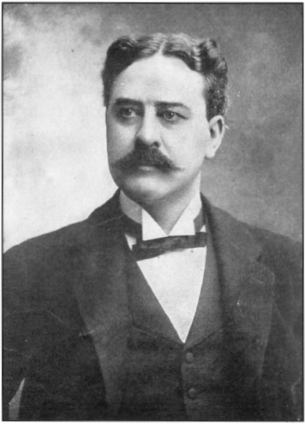

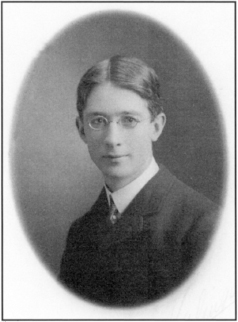

Charles W. Collins in 1903, the cub reporter who covered the theatre’s opening and returned to report on the disaster. (Author’s Collection)

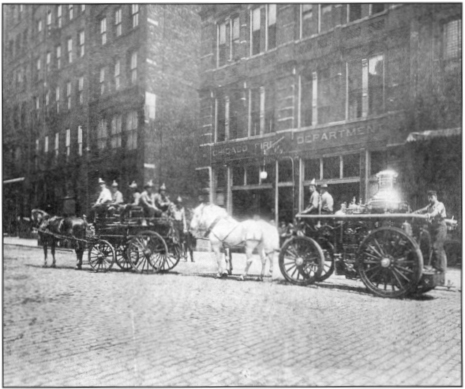

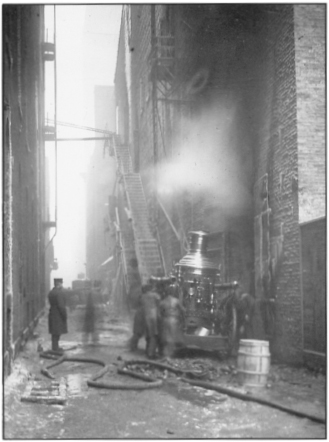

A typical engine company, Chicago Fire Department, circa 1903. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

Couch Place, the morning after the fire. The Plank bridges can be seen spanning muddy “Death Alley” while a fire engine next to the scenery doors pumps tons of water out of the theatre’s basement. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

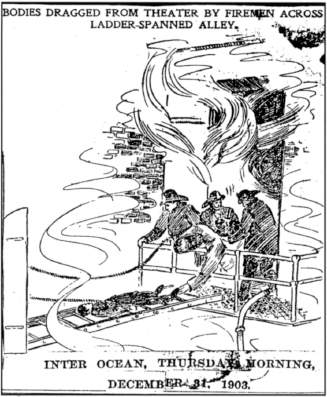

Without the benefit of spot photography to record the tragedy, newspaper sketch artists were used to depict the terror in “Death Alley” behind the theatre. (Author’s Collection)

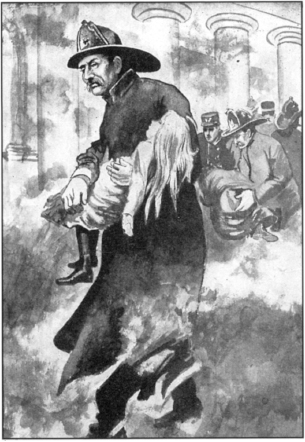

One weeping fireman told his boss, “I’m sorry, Chief, but I’ve got a little one like this at home. I want to carry this one out.” (Author’s Collection)

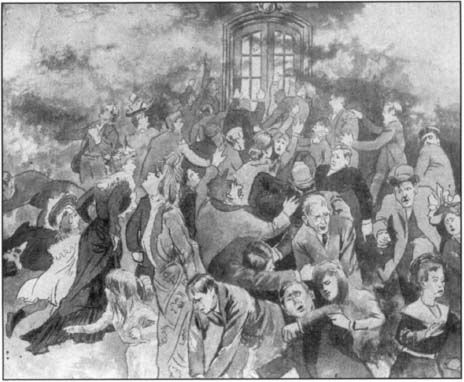

The New York Times described the victims as being caught in a human “whirlpool” and the Roman correspondent said that they perished “as if swept by … a Gatling gun.” (Author’s Collection)

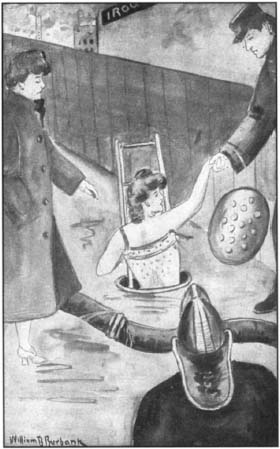

Many half-dressed chorus girls escaped from the theatre’s basement through a coal hole in Couch Place, helped out by one of Chicago’s thirty police department matrons. (Author’s Collection)

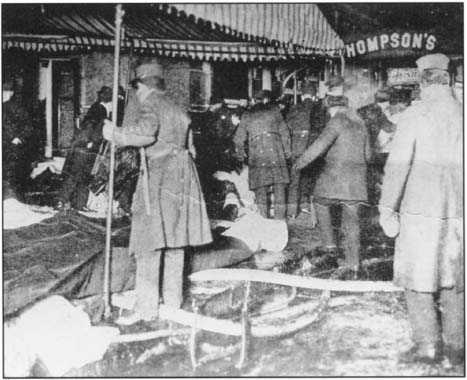

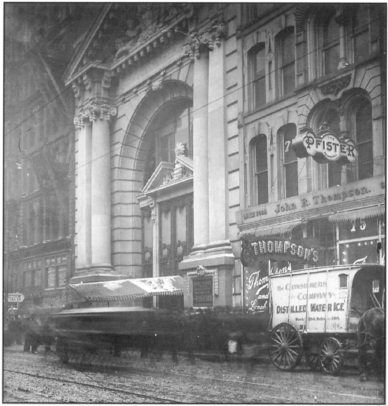

The scene on the sidewalk at the Randolph Street entrance as Collins saw it. Some victims lay in the slush. A few steps away in the background is Thompson’s Restaurant, which instantly became a first aid receiving station. (Brown Brothers photograph)

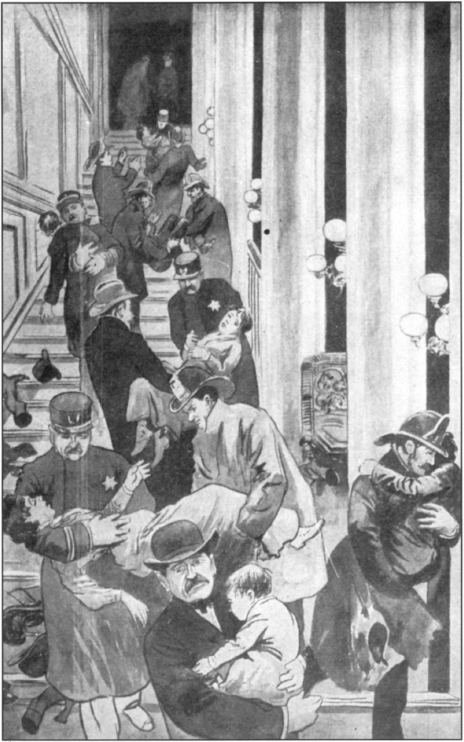

Civilian volunteers, including the first arriving newsmen, helped to carry victims down the staircases of the theatre’s Grand Promenade. (Author’s Collection)

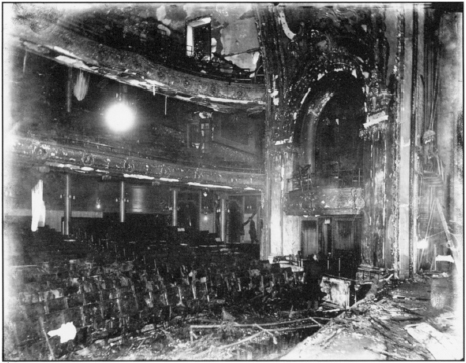

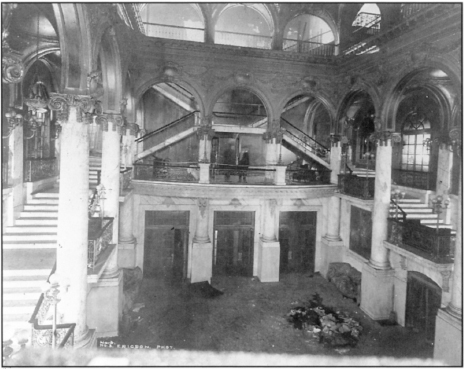

The Iroquois’ once-opulent interior. The fire started on the right-hand side of this photograph about 15 feet above the stage floor. It was from here that Eddie Foy repeatedly begged the audience to be calm. (David R. Phillips Collection)

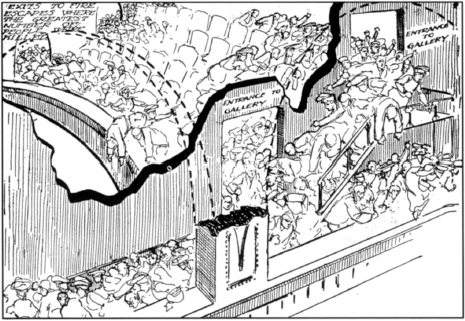

One newspaper diagramed the jamming at the gallery exits. (Author’s Collection)

As they groped their way toward the auditorium the smoke was thick and impenetrable to lanterns, but as it lifted fire and policemen could see piles of corpses in doorways. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

A line of victims awaiting identification. Blankets and sheets had been rushed to the theatre by major department stores. (Author’s Collection)

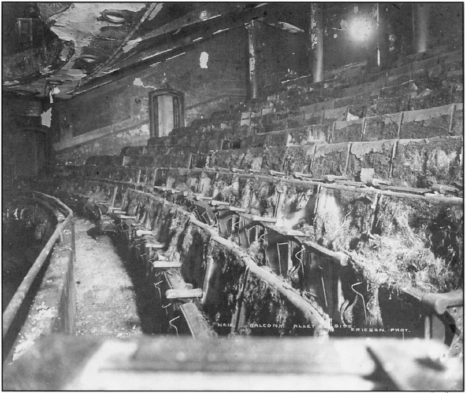

View of the balcony, alley side. Many of those in the balcony and gallery were trapped where they sat, in plush seats stuffed with hemp. (Author’s Collection)

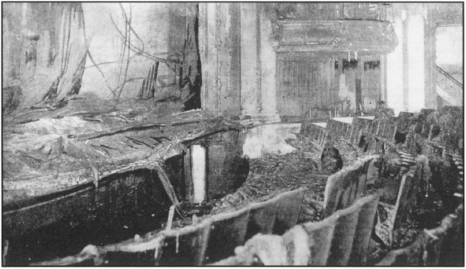

Flame-swept orchestra pit and front row seats. Many on the main floor escaped because the fireball that shot from the stage under the jammed curtain swept over their heads. (Brown Brothers photograph)

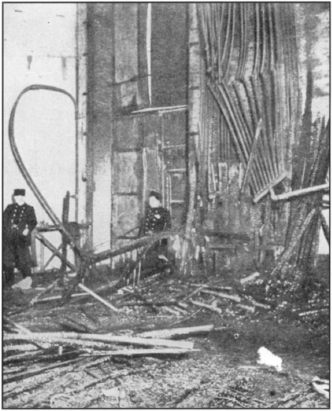

The scenery and rigging crashed to the stage with the force of a bomb, instantly knocking out the switchboard and plunging the house into darkness. (Author’s Collection)

The stage in ruins. A sudden illumination came from the stage when the safety curtain, jammed halfway down on a lighting fixture, burst into flames. (Author’s Collection)

A main exit from the balcony where victims piled up in the jammed doorways. (Author’s Collection)

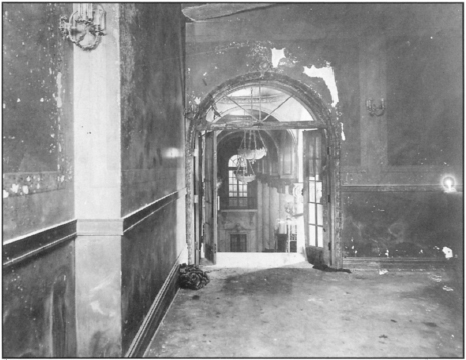

The Grand Promenade of what had been advertised as “The best theatre on Earth.” (Author’s Collection)

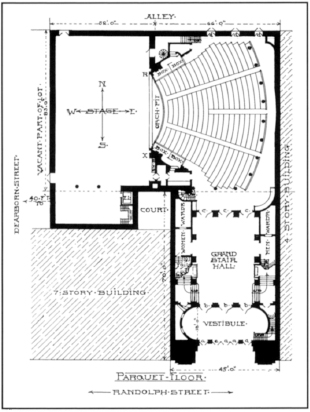

A diagram of the parquet floor of the Iroquois shows the location of the Grand Stair Hall, the main floor seating and the stage. (Courtesy Theatre Historical Society)

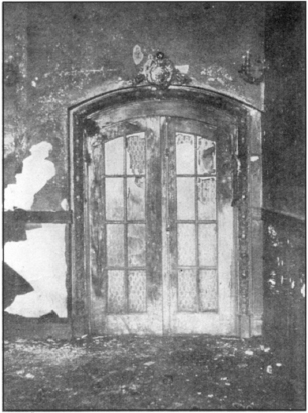

A door to a fire escape that could not be opened. Many died here. (Author’s Collection)

Top alley exits. The paint-blistered ceiling and walls of the gallery where Emil Von Plachecki said that it felt “like breathing a hot blast from a furnace.” (Author’s Collection)

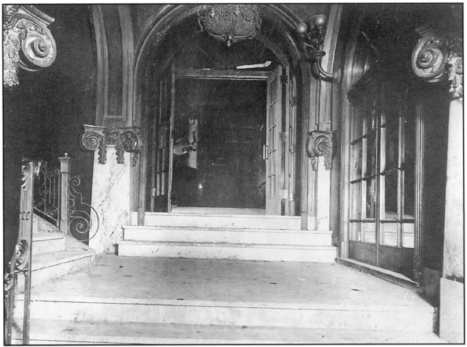

Converging stairways and a confusing mirrored door that was not an exit led to many fatalities here. (Author’s Collection)

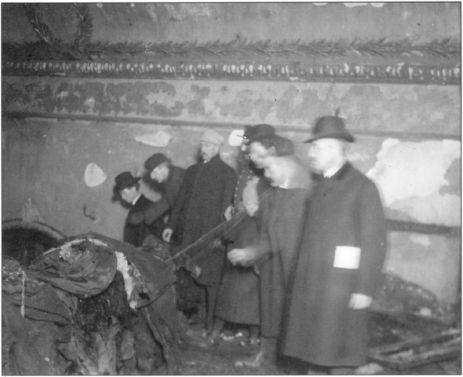

Inspection teams of city aldermen and other officials visited the theatre immediately after the fire. Many of them blamed one another for the tragedy. (Author’s Collection)

A passageway leading to a blind exit, where over 200 were found dead. (Author’s Collection)

This news photo was captioned “Looking for her children among the dead.” (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

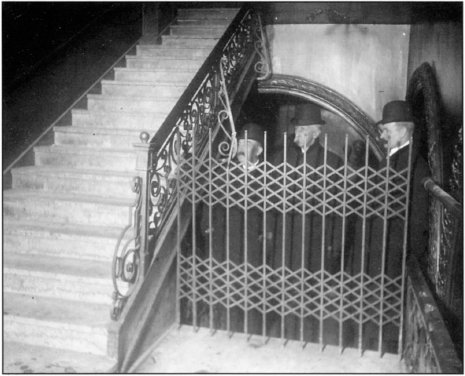

One of the theatre’s accordion gates that was locked to prevent those in the upper tiers from occupying empty seats in the more expensive downstairs parquet. (Author’s Collection)

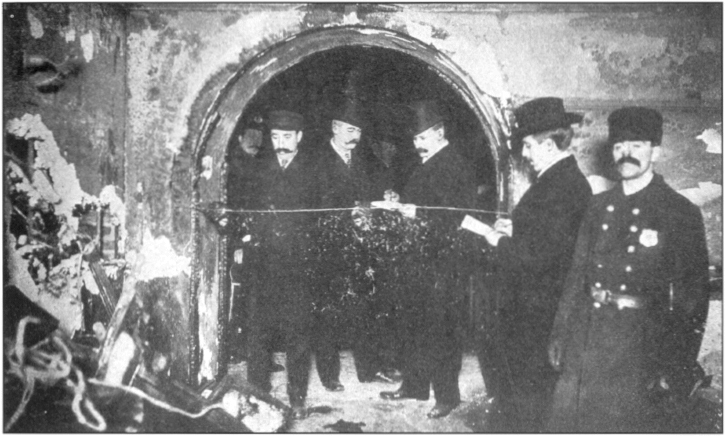

Officials inspecting the width of one of the main doorways leading from the balcony. (Author’s Collection)

The incomplete roof ventilation system, which was nailed down above the stage, forcing smoke, flames and toxic fumes into the audience. (Author’s Collection)

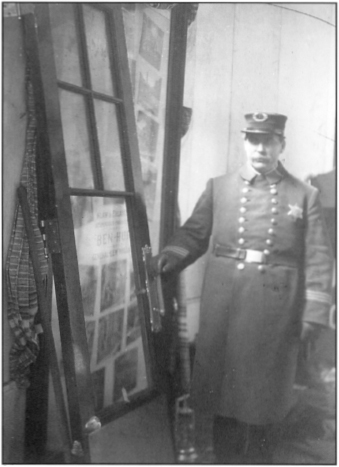

One of the locked doors that was smashed open as the audience attempted to get out of the theatre. (Author’s Collection)

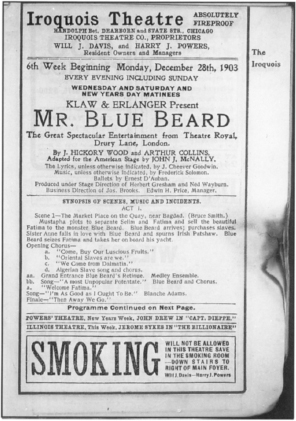

Partly burned program for Mr. Bluebeard. Note “Absolutely Fireproof” in the upper right corner. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

The Iroquois entrance the day after the fire. Note the absence of police or fire vehicles. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

This “extra” also contained a small announcement from a trans-Atlantic steamship company. (Author’s Collection)

Fireman Corrigan said: “People were jammed in the exits. We got a ladder and extended it from the fire escape to the [Northwestern University building]. We got a few [fatalities] out.” (Armond Fields Collection)

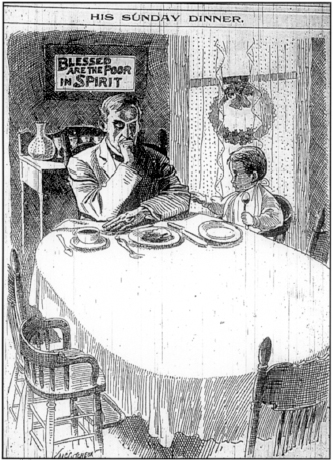

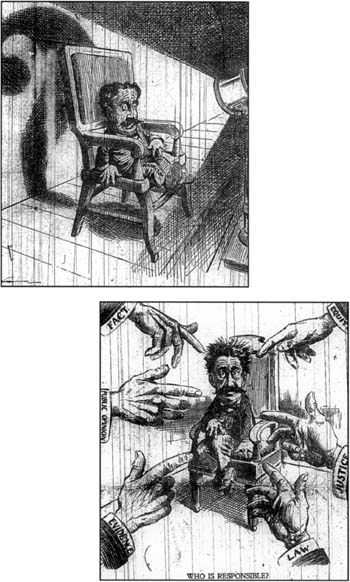

John T. McCutcheon drew a series of front page editorial cartoons about the tragedy, but none moved Chicagoans and out-of-town readers so much as this, which appeared during the first week of 1904. (Author’s Collection)

The Record-Herald’s Ralph Wilder also captured the anguish. The caption of this page one cartoon, “The Vacant Seat,” said it all. (Author’s Collection)

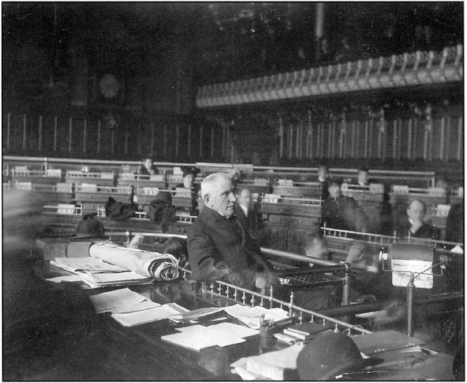

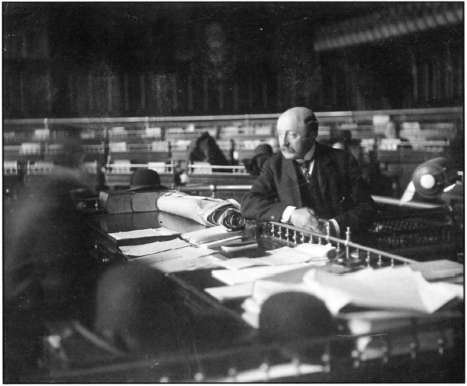

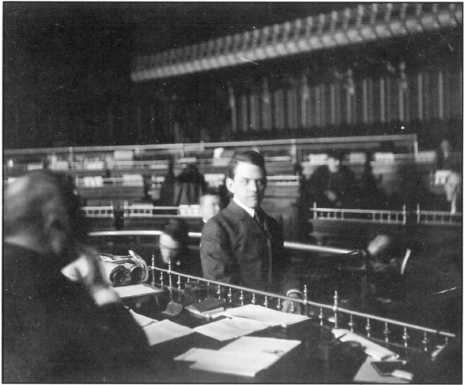

The coroner’s inquest was held in Chicago’s City Hall. The owners of the theatre, Will J. Davis (ABOVE) and Harry Powers (BELOW) were among 200 witnesses who testified. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

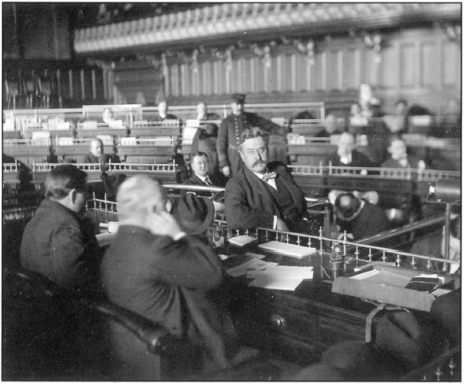

Mayor Carter Harrison (ABOVE) was a star witnesses. The Iroquois architect, Benjamin H. Marshall (BELOW), said he studied every theatre disaster in history to avoid errors in the design. (Courtesy Chicago Historical Society)

Mayor Harrison, who was vilified by many of the nation’s newspapers, moved quickly to tamp down criticism of his administration, with little effect. (Author’s Collection)

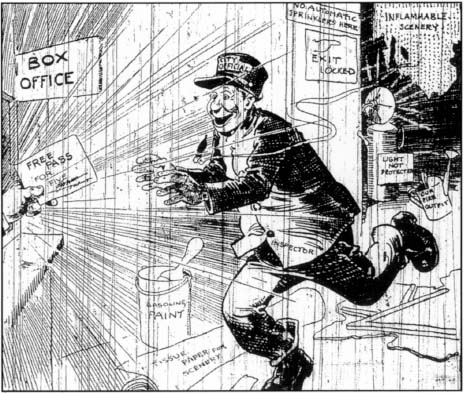

Chicago building inspectors were ridiculed. This cartoon shows one official grabbing for a free pass to the show, oblivious to the obvious dangers. (Author’s Collection)

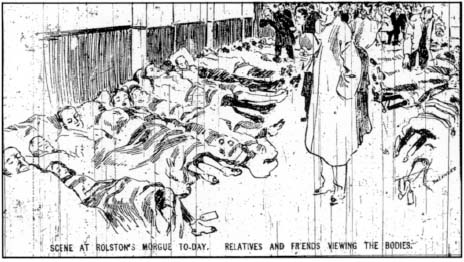

In some funeral parlors, victims were laid out neatly on floors and over New Year’s 1904 thousands of friends and relatives stood in the cold waiting their turn to make identifications. (Author’s Collection)

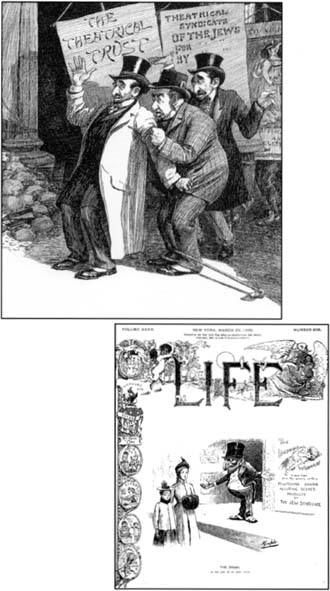

Years before the fire occurred, New York’s Life magazine attacked the Theatrical Trust in a series of vicious anti-Semitic cartoons including this detail (above) from a centerfold which parodied words from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. In the cartoon at right, the “hooknosed theater owner is inviting passersby to see ‘The Immoral Woman’…. Produced by The Jew Syndicate.” (Author’s Collection)