Question: Does China seek to drive US military forces out of Asia?

- No

- Yes

In many ways, this question brings us back to our discussion with Professor John Mearsheimer at the beginning of this book. Recall that he insists that over time, because of the dynamics of great-power politics, China must inevitably seek to be the regional hegemon in Asia as a matter of both self-defense and survival.

If Mearsheimer is right, the answer to the above question must inevitably be yes. That is, China can never be the hegemon of Asia as long as the United States remains the dominant power in the region.

The question, of course, about this particular question is whether there is any real evidence beyond the speculation of a mere political scientist to support the provocative assertion that China seeks to drive the US military out of Asia. Perhaps the best place to start looking for such evidence is in the actions, thoughts, and writings of one of the great military folk heroes of China—Admiral Liu Huaqing.

Vietnam best knows Admiral Liu as the commander who ordered the slaughter of Vietnamese sailors and soldiers during China's taking of the Paracel Islands in 1974. In a similarly dark vein, Chinese dissidents first think of Admiral Liu as the commander of the troops responsible for the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. These dark-prince clouds on his record notwithstanding, Admiral Liu will likely be best remembered as the father of the modern Chinese navy who once famously quipped that he would “die with his eyes wide open” if China did not have its own aircraft carrier before he passed away.1

Fig. 7.1. Admiral Liu Huaqing, the “father” of the modern Chinese navy and architect of the strategy to drive the US out of the Asia-Pacific, meets with Admiral James A. Lyons Jr., commander in chief of the US Pacific Fleet, in 1986 during a ceremony celebrating the first visit by US Navy ships to China in forty years. (Photograph by the Department of Defense, November 1, 1986, from the National Archives and Records Administration.)

For a figure as important as Liu, he is surprisingly obscure outside of China. However, during the 1980s, when Deng Xiaoping was famously converting China into a mercantilist global trader, it was Liu, as Deng's right-hand man, commanding China's navy.

At this propitious time of Deng's economic revolution, China was still primarily a continental power with little perceived need for the global projection of naval power. However, even as Deng was busily opening China to global trade, Admiral Liu was having a “parallel vision.”2 In this vision, Liu could see very clearly that it would eventually fall upon his own navy to protect the global trading routes Deng was busily building; Liu began working in earnest to forge a navy to rise to that globalized China occasion.

In this sense, Liu was very much what Professors James Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara of the US Naval War College have called a “Mahanian” figure. In the nineteenth century, it was Alfred Thayer Mahan—second president of the college and himself the forefather of the modern American navy—who pioneered the concept of global naval force projection as being critical to the economic prosperity of a nation.

In Mahan's world, it was only through the command of the seas that such prosperity could be assured. Such command, in turn, depended on two key parameters: (1) the industrial capacity of a nation to produce sufficient merchant ships and naval fleets to access vital trading routes, and (2) a system of forward bases that could service both merchant and military vessels.

According to Holmes and Yoshihara, while Liu staunchly denied being a follower of the Western imperialist Mahan, his actions have belied his Mahanian intentions.3 Indeed, it was Liu who first articulated the three-step Mahanian strategy that China appears to be closely following to this day.

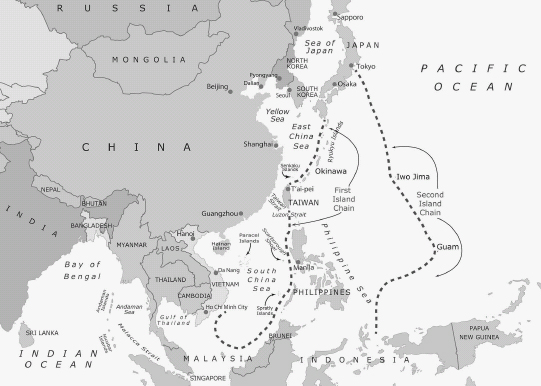

In Liu's vision, the critical first step was for China to break out of what he called the “near seas” and the “First Island Chain.” As has been noted, this First Island Chain runs from the northern tip of the Kuril Islands, down through the home islands of Japan, all the way to the southern tip of Japan's Okinawan territories. As the centerpiece and rough center point of the First Island Chain, the line defining this chain next passes through Taiwan and then across the Luzon Strait to the Philippines and down to Malaysian Borneo.

Of course, the “First Island Chain” metaphor is just that; there are no real chains strung across the waters of the East and South China Seas. Imaginary though the island chain may be, it is a metaphor that nonetheless weighed heavily on the mind of Admiral Liu, and it continues to be an obsession with Chinese strategists to this day.

In fact, China's focus on breaking out of the First Island Chain is entirely appropriate because of the very real constraints this chain poses for China's navy. One clear problem is that Liu's “near seas” are riddled with choke points; another is that China's surface ships are easily ranged by missiles or fighter jets from American forward bases in countries like Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea.

Map 7.1. Map of the First and Second Island Chains.

To Admiral Liu, therefore, it was painfully obvious that the first step to achieving global naval supremacy was to break the bonds of the First Island Chain. As to how that might be done, that will be the topic of our next chapter. For now, know that the second step in Admiral's Liu's recipe for Mahanian supremacy was breaking out of the “Second Island Chain.”

This Second Island Chain starts at the midpoint of the Japanese home islands. It then swings out into the Pacific over to the Northern Mariana Islands, which include most notably Saipan. The line of the Second Island Chain next travels to its rough midpoint at Guam. and from there it moves over to Palau, finally ending at Indonesia's Papua Province and Papua, New Guinea.

What each of these Pacific Island links in the Second Island Chain have in common is their strategic importance as “stepping stones” that were used by the US Navy to fight its way back from a bloodied and battered Hawaii through the Pacific to eventually be in a position to bomb the Japanese home islands, and thereby force the Japanese to surrender. This is a history that was certainly not lost on Admiral Liu. Today, Guam—once the site of one of the costliest battles of World War II—looms particularly large as a strategic American base, anchoring the Second Island Chain in much the same way that Taiwan anchors the First Island Chain.

For Admiral Liu, the goal was to break out of this Second Island Chain by the year 2020, and the now-aircraft-carrier-equipped Chinese navy appears well on its way to hitting this target. Liu, no doubt, is lying in his grave both with his eyes firmly shut and a smile on his face.

As for the third step in Admiral Liu's strategy was for China to achieve global naval supremacy by the year 2050. In fact, the scope of Admiral Liu's vision was absolutely breathtaking given that he articulated this vision back in an era when the Chinese navy was more akin to a coast guard than a global fighting fleet.

Today, there is considerable evidence both from Chinese military documents and from Western military analysts that China's strategic path is closely following Admiral Liu's three-step blueprint.4 Unfortunately for the cause of peace, this is a blueprint that by definition is a zero-sum game. Indeed, if China succeeds in breaking out of the First and Second Island Chains and commanding global waters, it will only be able to do so through the defeat—or acquiescence—of the US Navy.