Chapter Four

Blessed Are the Barren

Lynching, Reproduction, and the Drama of New Negro Womanhood, 1916–1930

I think the loveliest thing of all the lovely things in the world is just being a mother! —Angelina Weld Grimké, Rachel (1916)

Nothing lies nearer the heart of the colored woman than the children. —Mary Church Terrell, “Lynching from a Negro’s Point of View” (1904)

On March 9, 1892, there were lynched in this same city [Memphis] three of the best specimens of young since-the-war Afro-American manhood. —Ida B. Wells, On Lynching: Southern Horrors (1892)

Agnes Milton had taken a pillow off of my bed and smothered her child. —Angelina Weld Grimké, “The Closing Door” (1919)

This is not a story to pass on. —Toni Morrison, Beloved (1987)

African American women have, from the start, been vulnerable in their reproductive lives. Contemporary theorists, historians, and novelists—as well as nineteenth-century slave narrators and abolitionists—have repeatedly examined and analyzed that vulnerability. Hortense Spillers succinctly argues that, in a context of slavery, “the customary lexis of sexuality, including ‘reproduction,’ ‘motherhood,’ ‘pleasure,’ and ‘desire,’” is “thrown into unrelieved crisis.”1 In her 1861 Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Harriet Jacobs experienced and clearly understood that crisis, explaining that even had she been granted permission by her master to marry her free black lover, their children would have had to “‘follow the condition of the mother.’ What a terrible blight that would be on the heart of a free, intelligent father!”2 At first, Jacobs’s focus in this passage on her lover’s emotional state, rather than her own, might seem misplaced. But we must take into account, as did she, the complexities both of her particular situation as a fertile black slave woman in love with a free black man—and of the intertwining of race, gender, and reproduction within a slave economy. Gendered and raced experiences of parenthood within such an economy call for precise analyses like Jacobs’s. She points out (radically, for her time) that white women in slave-holding families did sometimes quite willingly bear children by their male slaves, but that those children were treated differently than children born to black women impregnated by white men:3 “In such cases [white mother and black father] the infant is smothered, or sent where it is never seen by any who know its history. But if the white parent is the father, instead of the mother, the offspring are unblushingly reared for the market” (52). Frederick Douglass offered a similarly cogent analysis of the capitalist, patriarchal, and white supremacist dynamics underpinning such reproductive and sexual politics, an analysis that has yet to be improved on: “Slaveholders have ordained, and by law established, that the children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers; and this is done too obviously to administer to their own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for in this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.”4 Douglass, like Jacobs, offers his own family’s history as an example of such politics of race, sex, and capital. In speaking of his grandmother, Douglass explained: “She had been the source of all his wealth; she had peopled his plantation with slaves; she had become a great grandmother in his service.”5 In other words, black slave women become the lineal vehicles for the production of white wealth in the form of their children, regardless of the identity of the father. Thus the domestic-familial space that mid-nineteenth-century white, middle-class social ideologies viewed as private and sanctified was anything but that for unfree African Americans. As Hazel Carby has shown, conventional constructions of womanhood, domesticity, and motherhood were not designed to fit black women in the nineteenth century.6 Jacobs could not possibly locate secure subjectivity through maternity: “There was a dark cloud over my enjoyment,” she says of her infant son; “I could never forget that he was a slave. Sometimes I wished that he might die in infancy” (62). Indeed, according to Angeletta Gourdine, black infanticide in the context of slavery becomes “paradoxically an ultimate protection of life.”7

But the end of slavery did not mean that motherhood and fertility became substantially less vulnerable or troubled states for black women. Likewise, the trope of an African American woman’s wishing for her children’s death did not disappear with emancipation.8 Long before Toni Morrison recovered the tragic history of Margaret Garner in Beloved (1987), African American women characters began again, as of the 1910s and 1920s, to imagine and even hope for their children’s deaths, with lynching’s emergence as the paradigmatic modern form of the oppression of black people in this country—what Jacqueline Goldsby terms “the image that compresses the horrific brutality of America’s racial history with regard to African-Americans into a singular act.”9 The return of the nineteenth-century trope of black women’s choosing childlessness—or, even more grim, committing infanticide—in response to lynching suggests that childbearing becomes a renewed site of trauma for African Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With at least 5,125 lynchings taking place in the United States between 1882 and 1939,10 such repeated acts, across generations, of ultimate home invasion threw into relief the impossibility of treating even the post-emancipatory black home as a refuge, or modern versions of domesticity and childbearing as effective “allegories of political desire,” to use Claudia Tate’s apt phrase.11 However, while Mary Church Terrell famously and persuasively argued that lynching was “the aftermath of slavery,”12 it is important to note that it was not therefore identical with slavery. Lynching functions as a specifically modern means of racial terrorism—quite distinct from slavery. As a kind of extra-institutional complement to Plessy v. Ferguson, lynching served on a local, familial level to block African Americans’ from achieving full citizenship and secure middle-class subjectivity. African American women writers responded to this new, modern form of racial-domestic violence by stretching literary form to—and beyond—its limits in order to enact their protests against it and against a modernity that permitted it.

The cross-generational trauma of lynching was represented by women writers of the Harlem Renaissance through what I would term “allegories of domestic and political protest,” in a genre invented by New Negro women writers during the 1910s: antilynching drama. Angelina Weld Grimké, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Alice Dunbar Nelson, Mary Burrill, and Myrtle Livingston all wrote antilynching plays between 1916 and 1930. Significantly, Grimké also repeatedly wrote on the subject of birth control and maternity for black women, often within her antilynching plays and short stories. Gloria Hull has observed of Grimké: “Lynching and the sorrow of having children are the dual themes of the drama and fiction that she produced before the Renaissance heyday, so much so that even a radical partisan wonders about her absolute fixation upon these subjects.”13 Grimké did in fact return again and again to those two subjects—lynching and maternity—to the dismay of both Hull and Tate; the latter has observed that “had it not been for Grimké’s obsession with rendering lynching . . . and . . . pathetic repudiations of motherhood, her writing might have had a broader creative plateau on which to develop.”14

But Grimké was not alone in her “fixation,” her “obsession,” and the repetition Hull and Tate note constitutes not so much an aesthetic failing as a stark literary-formal and performative protest. Indeed, the three most compelling—and interrelated—features of New Negro women’s nearly compulsive representations of lynching are, one, their psychoanalytic underpinnings (note the critics’ own terms: “fixation,” “obsession”); two, their function as specifically modern and literary forms of protest; and, three, their linkage of lynching and black motherhood as symbolic and literal—that is, as psychosocial—structures. Whereas most analyses of lynching—both period and contemporary—have emphasized white women’s and black men’s (and sometimes white men’s) sexuality, it is the sexuality and reproductive lives of modern black women that centrally concern Grimké and all of the other antilynching dramatists; neither their writings nor lynching itself can be understood apart from those concerns.15 As we have begun to acknowledge the centrality of lynching in twentieth-century U.S. psychosocial and political history, there has been developing a body of scholarship on lynching and on lynching protest. A number of historians have acknowledged the central role black women played, especially through their club work, in agitation against lynching and for the Dyer bill (never passed), which was to have designated lynching a federal crime.16 But, so far, there has been relatively little literary-critical scholarship on black women’s antilynching plays of the 1910s and 1920s, works that represent perhaps the period’s clearest and most literal enactments of protest, not only against lynching, but also against the intense institutionalized and ritualized forms of racism and sexism that shaped modern black women’s lives, especially their reproductive lives.17

The antilynching plays offer a scathing indictment of an entire racist, morally inverse modern social order, a social order in which the best black women repeatedly renounce motherhood as a result of the repeated lynching of the best black men. In her notes about the process of writing and revising her best-known work, Rachel (1916), Angelina Weld Grimké declared: “I drew my characters, then, deliberately from the best type of colored people.”18 In addition to Rachel, Grimké’s short stories “Goldie” and “The Closing Door,” Mary Burrill’s play Aftermath (1919), Myrtle Livingston’s play “For Unborn Children” (1926), and Georgia Douglas Johnson’s plays A Sunday Morning in the South (1925) and Safe (1929) all represent the finest sons, brothers, and husbands as becoming victims of lynch mobs. Conversely, much New Negro women’s writing, in particular Nella Larsen’s novel Quicksand (1928) and Mary Burrill’s play “They That Sit in Darkness” (1919), represents “Old Negro” women of the South as not only rural and unsophisticated but also disproportionately fertile and prolific. In the context of anti-lynching fiction and drama, repetition thus is not an individual psychological response or symptom and certainly not a writerly error; it is a shared representation of the social symptoms of a modern lynching culture that perversely selects against the “fittest,” generation after generation. As a result, antilynching dramas, indeed a wide range of New Negro women’s writings, use and rely on the vocabulary of such characteristically modern discourses as psychoanalysis and eugenics, even as they challenge their “truth,” their applicability to the lives of modern African Americans. According to Grimké, Burrill, Livingston, Douglas Johnson, and Larsen, the New Negro Renaissance—a movement whose very title signified the birth of newly fit, modern African American subjects—could not be sustained in the modern United States. The project of creating improved black subjectivity (the intraracial uplift of the Harlem Renaissance) and the counterweight of lynching (the simultaneous interracial enforcement of white supremacy) combined to produce modern African American and mixed race characters who are made crazy, again and again, by dominant social formations that select against them. All the antilynching dramas and stories register, through their repetitions and ruptures of literary form, the damage to individual and collective black subjectivities and psyches rendered by such unnatural selection.

As I argued in chapter 1, racial uplift in the 1910s and 1920s was, for “race men” such as W. E. B. Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson, clearly intertwined with eugenics. In a feminist analysis, Du Bois argued that “only at the sacrifice of intelligence and the chance to do their best work can the majority of modern women bear children,”19 but as a eugenicist Du Bois insisted that Negro “families of the better class” should have more children.20 New Negro women thus faced the paradoxical duties of simultaneously being and reproducing the New Negro. Of course, one could argue that black women had, from the start in the Americas, been treated as functional reproducers in a way that, if not explicitly eugenic, was certainly unrelated to “pleasure” and “desire.”21 Black slave women were positioned as “breeders” whose children would by law follow their mother’s condition and thus expand their master’s property. Because of that specific history surrounding their reproductive and sexual lives, modern African American women were positioned quite differently than were white women in relationship to the discourses and debates of the 1910s and 1920s surrounding New Womanhood, free love, and birth control. As Michele Mitchell concisely argues, “Stereotypes concerning black sexual appetites kept many aspiring and elite race members from engaging in” the period’s “social emancipations” regarding sexuality.22 But eugenics, on the other hand, affected the meaning of childbearing for all modern women; regardless of race, all became potential vehicles of national and racial improvement during the peak years of American eugenics (not coincidentally, also the era of antilynching drama).

The scientific notion of breeding better human beings did not emerge explicitly until the end of the nineteenth century and was not fully articulated by American and English social scientists until the early twentieth century. Astonishingly widespread and accepted by many activists and intellectuals of a variety of political outlooks and across racial lines, eugenics inevitably left its mark on the thought and discourse of modern African American women as well. But they were far more likely to resist its allure. A number of New Negro women writers and activists, although generally in favor of black women’s access to and voluntary use of birth control,23 expressed suspicion about the scientific or social regulation of reproduction (not surprisingly, given the legacy of slavery’s politics of fertility), while they offered in their antilynching writings a remarkable challenge to the period’s competing and complementary discourses of white supremacy, eugenics, psychoanalysis, and bourgeois racial uplift.24 Writers like Grimké and Burrill were clearly protesting interracial oppression, as were Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglass in the nineteenth century, but they were protesting, as well, a specifically modern intraracial and gendered oppression—that is, African American ideologies of uplift that emphasized black women’s domestic and reproductive value. For example, in Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, when James Vayle, the ex-fiancé of protagonist Helga Crane, insists that she have children in order to improve the race, she replies: “I, for one, do not intend to contribute any to the cause.” In just this way, Larsen, Grimké, and a number of other early-twentieth-century African American women writers rejected the role of breeder both literally and literarily, supplementing their “express explicit and unreserved racial protest,” as Tate puts it,25 with feminist protest against the regulation or restriction of black women’s bodies and lineages by men of any color. And they regularly linked the two—racial protest and feminist protest—through their repeated representations of lynching in relation to reproduction.

For Grimké, Burrill, Douglas Johnson, and Livingston, lynching represented a kind of extract of racial oppression that violently performed a moral and juridical inversion at the same time that it dramatically revealed the wholly ideological, gendered, and racially determined nature of much of the period’s ways of knowing modernity itself. In condemning lynching, they implicitly challenged the fundamentally modern discourses of eugenics and psychoanalysis, discourses that emerged out of and described a crazy-making social order that at once permitted lynching and promoted the breeding of better human beings. Thus, if nineteenth century African American writers had had to reconstruct womanhood,26 early-twentieth-century African American writers had to reconstruct modernity itself. Their first task was to expose that inversion within the modern social order, and, for many of them, a focus on lynching did just that. There is, for example, a deeply troubled and troubling passage in James Weldon Johnson’s 1911 Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man, a passage that makes sense only in the context of such an inversion. Johnson’s nameless mulatto narrator has decided not to pass for white—although he can—and has traveled south on his mission to collect Negro spirituals in order to reinterpret them as classical music. In the countryside outside Macon, Georgia, he witnesses a lynching. He describes his response to the savage scene: “I walked a short distance away and sat down in order to clear my dazed mind. A great wave of humiliation and shame swept over me. Shame that I belonged to a race that could be so dealt with; and shame for my country.”27 Feeling “as weak as a man who had lost blood,” the narrator decides at this moment to abandon his Negro identity and his musical mission—that is, to lose specifically his black blood, in order to pass as white. What was “driving me out of the Negro race,” he explains, is “shame” (499). Although the logical response to witnessing a lynching would seem to be shame at his whiteness, the narrator is in fact ashamed “at being identified with a people that could with impunity be treated worse than animals” (499). The inverted psychological response of the narrator mirrors the inversion of legal and moral order embodied in the practice—indeed the “brutal public ritual” and performance—that is lynching;28 the modern mixed-race individual cannot interiorize a justice that fits the crime, because the individual mind and its internal sense of justice is sacrificed to the collective immorality of an institutionally condoned racial vigilantism.

By exploring the intersection of lynching and reproduction, Angelina Weld Grimké, Mary Burrill, Georgia Douglas Johnson, and Myrtle A. Smith Livingston add another layer to James Weldon Johnson’s “inversion” analysis of white supremacy and racial terrorism, one that relates directly to black women’s sexuality and fertility. Indeed, it is not coincidental that two of Grimké’s lynching/motherhood stories were published in the Birth Control Review: “The Closing Door” in 1919 and “Goldie” in 1920. Grimké’s exposure and exploration of the psychological impossibility of healthy black motherhood in the 1910s and 1920s at once marks her as a modern thinker and her characters as highly civilized—and explicitly raced and gendered—discontents who repeatedly challenge and complicate the era’s most prominent social and scientific discourses. Both Carolivia Herron and Claudia Tate have analyzed Grimké’s own psyche in relationship to her thematics of frustrated black maternity, linking Grimké’s apparent lesbianism with her choice never to marry or have children.29 But such psychoanalysis of the author may not be as productive as analysis of the ways that her characters and plots are, in turn, analyzing their own social milieu.

Grimké’s antilynching play Rachel, including its setting, characters, speech, plot, and structure, enacts an especially clear “allegory of domestic and political protest,” with ellipses, pauses, silences, repressions, and repetitions working as literary signifiers of familial trauma and of social dissent against an unjust modern social order. Rachel was first produced in Washington, D.C., in 1916; it takes place entirely within the top-floor flat of the allegorically named Lovings,30 an African American family—Rachel, the daughter; Tom, the son; Mrs. Loving, the mother; and Jimmy, a neighbor boy adopted by Rachel. The other main character, John Strong, is Tom’s friend and Rachel’s eventual suitor. The play traces how Rachel eventually breaks down after being, at the beginning of the play, a high-spirited teen whose primary goal in life is to become a mother: “I think the loveliest thing of all the lovely things in the world is just being a mother!”31 Rachel and Tom’s sentimentalized and apparently happy domestic life is disrupted, almost from the start, by their mother’s confession that, ten years earlier to the day, their father and older half brother had been lynched. By play’s end, with repeated instances of racial discrimination afflicting each of the characters, an adult Rachel hysterically renounces marriage to John Strong and childbearing in general, refusing to bring any more black children into the world to suffer as her family has.

The play’s investment (or, more precisely, disinvestment) in eugenic thinking emerges early on. Four years after their mother’s confession, on the anniversary of their father’s and brother’s death, Tom bitterly considers the family’s current situation: “Rachel is a graduate in Domestic Science; she was high in her class; most of the girls below her in rank have positions in the schools. I’m an electrical engineer—and I’ve tried steadily for several months—to practice my profession. It seems our educations aren’t of much use to us: we aren’t allowed to make good—because our skins are dark. (pauses) In the South today, there are white men [he is referring to the men who lynched his father and half brother]—(controls himself) They have everything; . . . With ability, they may become anything; and all this will be true of their children’s children after them. . . . Our hands are clean;—theirs are red with blood—red with the blood of a noble man—and a boy. They’re nothing but low, cowardly, bestial murderers. The scum of the earth shall succeed” (49). Lynching represents, then, a most unnatural form of selection, one designed to reinforce white supremacy and sustain black powerlessness, regardless of the quality and education of either whites or blacks. “Low” whites can murder “noble” blacks, and the result—that the lynchers, the worst of humanity, will “succeed”—is decidedly dysgenic for both races. Grimké’s play thereby exposes the ways that social Darwinist and eugenic thinking is at best irrelevant, and at worst both morally and scientifically backward—given the racial injustice, white hegemony, and racial terrorism of the 1910s and 1920s. At the same time, Tom’s barely controlled speech—with its dashes, pauses, and ellipses—reflects lynching’s damage to modern individual and collective subjectivities and psyches as well as the concomitant ruptures and “fixations” in the play’s language and structure.

The lynching that had taken place before the beginning of the play’s action stands as the original traumatic and dysgenic event in the Loving family. In recounting the events that led up to the lynching, Mrs. Loving describes their father to Rachel and Tom as “a man among men,” a “big-bodied-big-souled” man who “was utterly fearless” (40). Outraged at a lynching by whites (“a mob of the respectable people in the town”) of an innocent black man, their father had “published a most terrific denunciation of that lynch mob” and stood by his denunciation, despite death threats (40). As a result, a lynch mob came to their house.32 Mrs. Loving describes the scene: “We were not asleep—your father and I. They broke down the door and made their way to our bedroom. Your father kissed me—and took up his revolver. It was always loaded. They broke down the door. . . . (pauses) Your father was finally overpowered and dragged out. In the hall—my little seventeen-year-old George tried to rescue him. . . . It ended in their dragging them both out. My little George—was—a man!” (41). This highly suggestive scene shows the absolute termination of one lineage: George was Mrs. Loving’s only child from a prior marriage (as she explains, when she married Mr. Loving, she was a widow and her son George by her first marriage was seven). But her odd reference to their not being asleep, though it may simply suggest the Lovings’ apprehension, could also suggest that the lynch mob was interrupting love-making; as such, they may have been interrupting another lineage as well, forcing Mr. Loving to substitute violent resistance/gun/“revolver” for reproduction/ phallus/“loving” in a kind of socially compelled “choice” of Thanatos over Eros. Indeed, as the play figures it, to be a “man among men” constituted a death wish for African American men in the United States in the South in the 1910s and 1920s.

Lynchers are repeatedly represented (not only in Grimké’s plays but also in nearly all black women’s antilynching stories and dramas of the 1910s and 1920s) as victimizing the very best black men and fathers33—and as leading the very best black women and mothers to choose, or at least to consider, childlessness or infanticide. Tom, the young son/ brother in Georgia Douglas Johnson’s A Sunday Morning in the South, announces his plan to fight lynching: “I mean to go to night school and git a little book learning so I can do something to help—help change the laws . . . make em strong” (105). The energetic and promising Tom is, of course, eventually lynched, falsely accused of raping a white girl. Lynching represents, then, not just a weak but an inverted legal (and moral) order that leads in turn to inversions of other orders: eugenic, maternal, familial, psychological, and so on. Perhaps worst of all, in its very unnaturalness, lynching leads to unnatural selection: not only through its direct annihilation of the best African Americans by whites, but also through the reaction of self-annihilation by the best African Americans—at least as represented in much modern black women’s drama and fiction.34

In the 1910s and 1920s, that perverse social order showed little promise of improvement for African Americans. Jim Crow was the law of the land, and what Kirk Fuoss describes chillingly as the “peak years of lynching” stretched from 1880 to 1935.35 The repetitiveness that Hull and Tate note should be viewed, therefore, not as an aesthetic or thematic failing but as a necessary corrective to, and protest against, the repeated, cross-generational performance of lynching itself. As Tate herself has observed, in another context, “Unremitting racial trauma demands an unending supply of stories.”36 Thus, inasmuch as lynching constituted a protracted form of terrorism taking place generation after generation in a kind of “lynching cycle,”37 lynching protest, too, lent itself to repeated performance and so to drama.

The representation of such ultimate, and repeated, familial and racial trauma necessarily stretches literary form itself. The performance of lynching forms the play as it deforms conventional dramatic form. Indeed, the cyclical/generational nature of racial oppression in general, and of lynching in particular, is often represented and commented on explicitly within the antilynching plays. In Grimké’s Rachel, when Rachel brings home a neighbor child she has befriended and will eventually adopt, Mrs. Loving cries out: “Rachel, he is the image of my boy—my George!” Such reimaging and reimagining, mirrored by repetitions, dashes, and pauses, constitute lynching’s psychological and literary representational forms. Indeed, the play’s plot and action are, throughout, structured according to the anniversaries of that original lynching of George and Mr. Loving. Analogously, again and again, tragic African American heroines of antilynching fiction and drama observe that to bear children, especially boy children, is to provide fodder for lynchers’ insatiable, ongoing appetite for racial violence. As a result, in terms of classical theories of drama, there can be no catharsis in lynching plays for the characters,38 for African American playwrights, or for their audiences.39 As Andrew Ford convincingly defines it, “Tragic katharsis would be the specific form of [“pleasing and relaxing emotional”] response that attends the arousal of our emotions of pity and fear in an environment made safe by the fact that the tragic spectacle is only an imitation of the suffering.”40 We must realize that these plays offer, instead of an “imitation,” a representation of a profoundly unsafe and ongoing social reality. As long as performances of lynching continue, antilynching dramas must also repeat the representation of lynching in a perpetual absence of release or purgation.

The repetition among and within antilynching plays subverts not only conventional theories of drama, but also conventional psychoanalytic (both Freudian and Lacanian) theories regarding trauma and its aftermath, theories that owe much to the notion of catharsis and to classical drama in general.41 As Cathy Caruth concisely explains, “In its general definition, trauma is described as the response to an unexpected or overwhelming violent event or events that are not fully grasped as they occur, but return later in repeated flashbacks, nightmares, and other repetitive phenomena.”42 Thus, according to psychoanalytic theory, repetition results from the inability to have expected or the failure to have fully known the original trauma. Without full knowledge and understanding, the traumatized individual repeatedly returns—in dreams, nightmares, or flashbacks—to the original traumatic experience (96). But modern African American playwrights, along with their characters and audiences, did in fact “fully grasp” lynching because it was an external, predictable, often-repeated form of violent trauma that, in certain ways, was not only fully known but fully expected.

As William Storm has noted, black women’s plays of the modern era generally “featured domestic situations in which mothers and children were prominent, with the husband either deceased or absent,” and with “the event of a lynching . . . significant in the . . . action” so frequently that these elements may be considered “conventions.”43 But among the conventions of the antilynching plays is not simply the absent husband but the male—be it husband, father, son, or brother—whose return home has been delayed. When black men are late in these plays, lynching stands as the most feared and the most logical explanation. In Myrtle Livingston’s 1926 play, “For Unborn Children,” the grandmother, “a gentle, well-bred old lady” from “a refined family [of Negro descent], evidently of the middle class,” worries about her past-due grandson, crying, “it’s awful for him to keep us in this terrible suspense!”44 Likewise, in Georgia Douglas Johnson’s play Safe (1929), Liza, the pregnant wife of the hero John, and her mother, Mandy, repeat in a kind of unbearably anxious refrain: “I wonder where John is—,” “He oughter been back here before now,” “John ain’t back,” “Oh, where is John? Where is John?”45 Although John is not lynched in the play, another black man is, and the entire family, including Liza, can hear the “hoarse laughter” of the lynch mob outside (113). Immediately after the lynching has taken place, Liza gives birth, then strangles her newborn son. The doctor in attendance reports that “she kept muttering over and over again: ‘Now he’s safe—safe from the lynchers! Safe!’” (113). Men’s lateness in the plays thus brings with it a gruesome doubled suspense—a dramatic kind that lends itself particularly well to the stage and the temporality of performance, reinforced by a literal and horrifying tension. Given this second sense of “suspense” within the plays—black men may be attacked and hung by white mobs at any time for any reason—Liza’s and Mandy’s repetitiveness and Liza’s hysterical infanticide, like Rachel’s “convulsive laughter” as John Strong kisses her at the end of Grimké’s play, cannot be understood as conventional hysterical responses of the modern stage. “Hysteria,” as Elin Diamond argues, “in effect created the performance text for dramatic modernism.”46 But the abnormal symptoms here are not Liza’s or Mandy’s or Rachel’s, but the modern lynching culture’s. As Anne Cheng cogently argues in The Melancholy of Race, “The psychical experience of [racial] grief . . . is not separate from the realms of society or law but is the very place where the law and society are processed.”47 Yet the women in antilynching plays cannot truly be considered melancholic or neurotic individual subjects; the allegorical names of Grimké’s characters—the Lovings, John Strong—suggest that Rachel and her family represent, not diagnosable bourgeois modern individuals, but model modern African Americans afflicted, indeed annihilated, by racism. Rachel and her family, just like Liza and her family, cannot afford the luxury of personal, highly contingent neuroses; they must contend with the external, racialized pathologies of the modern United States—and as long as the lynching culture’s symptoms persist, so will the need for the antilynching plays and their representations of black women’s hysteria, compulsive repetition, and infanticide.

The antilynching plays written and produced between 1916 and 1930 thus depend on, while they also complicate, a then-emerging popular vocabulary of psychoanalysis, just as they both depend on and complicate the even more popular modern vocabulary of eugenics. In a compelling analysis of contemporary “feminist theory and practice in theatre and film,”48 Barbara Freedman has argued that a truly feminist

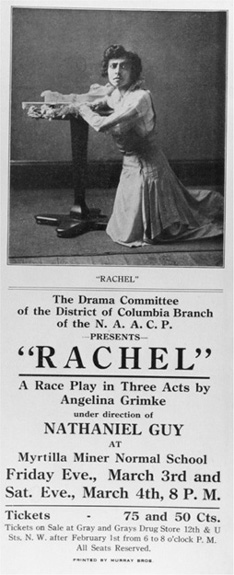

Playbill from a performance of Angelina Weld Grimké’s Rachel in 1916. Courtesy of Angelina Weld Grimké Papers, Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

conjuncture of “feminism, psychoanalysis, and theatre” is one that will “reflect and effect change” (60); to do so, it must “insert a difference in our construction of the subject and so . . . make a difference,” in part by undoing “the figuration of difference as [a] binary opposition” that is articulated through “phallocentric vocabulary” (56–57). But New Negro women playwrights disrupt not only “phallocentric vocabulary” but also white supremacist ideology, and they do so by means of a combination of difference (a black female central subject) and sameness (repetition). Grimké and Douglas Johnson neither believe in nor rely on a “binary opposition” of black and white; but they and their characters must nevertheless contend with that ongoing opposition as it was encoded in the 1920 U.S. census, in Jim Crow, and most especially in lynching. To put this more bluntly, the “castration” that is imagined by Freudians and Lacanians—and challenged by the white feminist psychoanalytic theory described by Freedman (58)—was not imaginary for African Americans between 1880 and 1930. They were fully conscious of both maintained “difference” and sustained punishment for that difference (a penalty that was anything but metaphorical). In response, antilynching dramatists offered sustained protest, with their repetitions serving to diagnose the nation rather than black women.

Grimké wrote a number of lynching plays and stories, and she also drafted several complete versions of Rachel, each with a different title.49 Her notes about this revision process suggest the intentional use of literary form to offer a psychosocial analysis of lynching centered on black women. For example, she explains that, in revising the passage in which Mrs. Loving decides to tell Rachel and Tom about the lynching of their father and stepbrother,

I have changed from “I believe it to be my duty.” to this:

MRS. LOVING.

“Yes.—I see now it is—my duty.”50

Indeed, over the course of several rewritings of the play, Grimké repeatedly revised Mrs. Loving’s story of the lynching and her decision to tell that story—in this instance by adding dashes and a time frame (“now”) which together express the elisions, silences, and pauses symptomatic of past trauma and of the process of telling and retelling that trauma in the present. But it is perhaps her revision of the play’s title that is most provocative, particularly in the context of New Negro womanhood and reproduction. Her next to last title for the play, Blessed Are the Barren, suggests that choosing not to have children becomes a positive action for African American women under the consistently hostile conditions of modernity. Lynching renders the feminist psychoanalytic project of re-centering and performing femininity in general, and mother-child relations in particular, irrelevant and impossible for modern black mothers: blessed are the barren. Grimké’s repetition is thus not so much with a difference, as Lacanian theory would have it, but repetition with a depressing, even hysteria-producing sameness. She and the other antilynching dramatists, were, therefore, “fixated” on lynching and maternity for good reason.

In the antilynching plays of Grimké, Burrill, and Douglas Johnson, black female protagonists repeatedly perform their maternal renunciations and infanticides. Because of this repeated juxtaposition of lynching and “barrenness,” there emerges an obvious thematic link between lynching and infanticide/sterility. But the repetition also points to an even deeper structural (and literary-formal) connection between lynching and reproduction. First, modern representations of black infanticide necessarily refer to a long legacy of crisis surrounding African American women’s reproductive lives, registering the unrelieved pressures on black female fertility even after the end of slavery. But there is, as well, a specifically modern dimension to the barrenness in the antilynching plays. Black women’s repeatedly traumatic experiences surrounding childbearing stands in symbolic correspondence to black men’s being lynched in the modern era; each is a gendered, generational oppression produced by white supremacy and patriarchy. As long as black women are not free both to control and to express their sexuality and fertility, they will be oppressed; as long as black men are at risk of being lynched, they will be oppressed. At the intersection of these oppressions reside black children, male and female, who must, generation after generation, contend with an unjust social order. Modern African American women’s antilynching plays understand and protest that still-living political economy of race and reproduction.

But the dramas of New Negro women challenged not only white-dominated social forms and discourses; there was an intraracial politics of reproduction being challenged as well. Indeed, many New Negro men were trying to set an agenda for black reproduction and thus to establish control over modern black women’s fertility. In an often overlooked passage in Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, Helga Crane’s ex-fiancé, James Vayle, urges her to breed:

James was aghast. “But Helga! Good heavens! Don’t you see that if we—I mean people like us—don’t have children, the others will still have. That’s one of the things that’s the matter with us. The race is sterile at the top. Few, very few Negroes of the better class have children, and each generation has to struggle again with the obstacles of the preceding ones, lack of money, education, and background. I feel very strongly about this. We’re the ones who must have the children if the race is to get anywhere.”

“Well, I for one don’t intend to contribute any to the cause.”51

James Vayle had his real-life counterpart in male race leaders such as W. E. B. Du Bois, who cautioned in a 1926 Crisis: “There are to be sure not enough children in the families of the better class.”52 E. Franklin Frazier concurred, arguing: “The whole social system in the South favors the propagation of the least socially desirable (in a civilized environment) among Negroes. The less energetic and resourceful fit easily into the rôle the white man has assigned the Negro, while the more energetic and resourceful leave or often fail to reproduce.”53 Although Du Bois and Frazier are not speaking explicitly either to or about middle-class black women—that is, New Negro women—their (pregnant) presence is necessarily implicit. Here lies the deep structural link between lynching and black women’s reproductive lives, regardless of class. If the essence of racial and gender oppression for African American men is the lynching cycle, for black women the essence of their oppression is the cycle of repeated childbirth within a racist and lynching nation; in other words, childbirth for modern black women is intimately connected to both gender and racial oppression (just as lynching is intimately connected to both gender and racial oppression for black men). First, black women bear the children who will surely suffer from some form of racism, if not lynching; second, repeated childbirth will just as surely prevent the women themselves from attaining true modernity in the form of middle classness, independence, and “New Negro” status.54

This bleak inter- and intraracial economy of fertility and lynching, sexism and racism, reproduction and tragedy, is one that not only the antilynching plays, but an even wider range of modern African American women’s writing expresses. Trouble seems inevitably to result from New Negro women’s having children. In Nella Larsen’s novel Quicksand, protagonist Helga Crane, despite her early declaration—“Well, I for one don’t intend to contribute any [children] to the cause”—ends up dying as a result of repeated childbirth. As the last line of the novel states: “And hardly had she left her bed and become able to walk again without pain, hardly had the children returned from the homes of the neighbors, when she began to have her fifth child” (135). The ending’s inconclusiveness (suspense) points to the endless, cyclical nature of the New Negro woman’s dying in and from childbirth. By contrast, Quicksand represents other women—those who might be termed “Old Negro”—as less at risk from the repeated childbirth that is lethal for the modern, urbane Helga Crane. From her first pregnancy, Helga never fits her final identity as rural southern pastor’s wife and serial reproducer. Nauseous and weak, she wonders, “How . . . did other women, other mothers, manage?”

“Tain’t nothin’, nothin’ at al, chile,” said one, Sary Jones, who, as Helga knew, had had six children in about as many years. “Yuh all takes it too ha’d. Jes remembah et’s natu’al fo’ a ‘oman to hab chillluns an’ don’ fret so.”

“But,” protested Helga, “I’m always so tired and half sick. That can’t be natural.” (125)

The passage suggests that childbearing comes as naturally as dialect to the southern, rural African American woman, whereas multiple childbirth is unnatural for the modern, New Negro woman. Linguistic “primitiveness” and fertility are thereby linked via an economy of geo-racial family politics. Sary functions almost as Helga’s contemporary ancestor; she resides in a still agrarian, premigration African American history. In other words, Sary’s incomplete diction—with the apostrophe as signifier—discloses her necessarily inadequate subjectivity in any authentically modern setting. She represents the rural and premodern, just as Helga (along with her complete command of standard English) represents the urban, the alienated: that is to say, the modern and the paradoxically unfit—another kind of unnatural selection. Middle-class, New Negro women like Helga were in fact far less likely to die from childbearing than were their working-class and poor sisters. Historian Michele Mitchell points out that while African American women’s overall fertility rate saw a decrease “beginning with the end of Reconstruction and lasting until at least 1930,” middle-class northern women were likely to bear fewer children than women in the “agricultural South.”55 Indeed, many of the prominent women of the Harlem Renaissance remained childless, including Hurston, Larsen, and Grimké. This is not to say, however, that middle-class black women writers were wholly unsympathetic to the plight of poor and working-class, or of southern and rural, fertile women.

Like Helga Crane, Mrs. Malinda Jasper in Mary Burrill’s short play “They That Sit in Darkness” (published in the Birth Control Review’s special “Negro Number” in September 1919),56 becomes a victim of repeated childbirth. Mrs. Jasper is the mother of a poor black family “in a small country town in the South in our own day” (5). She suffers from a “weak heart” (7) and is having difficulty recovering from the birth of her most recent child just a week earlier, yet she continues to work at her laundry business. At the same time, her daughter Lindy is packing a trunk in preparation for attending Tuskegee, her tuition having been sponsored by a northern white philanthropist. Mrs. Jasper’s husband Jim never appears in the play; we are told that he works from before the children wake in the morning until after they are asleep at night. Besides members of the Jasper family, the only other significant character is Miss Elizabeth Shaw, a visiting nurse–social worker who provides milk for the new baby, along with health advice for Malinda Jasper.57 Miss Shaw admonishes Mrs. Jasper for going back to work so soon after the delivery: “You will have to stop working so hard. Just see how exhausted you are from this heavy work! . . . I heard the doctor tell you very definitely that this baby had left your heart weaker than ever, and that you must give up this laundry work” (7). Mrs. Jasper replies with a dose of reality: “’deed, Miss ‘Liz’beth, we needs dis money whut wid all dese chillern” (7). We then discover that in addition to the seven Jasper children left at home, two other children have died and one daughter who “warn’t right in de haid” was impregnated by a white employer (rape, or at the very least coercion, is implied) and ran way. Not only that, but Mary Ellen, one of the seven left at home, has tuberculosis. As Miss Shaw puts it, “Well, Malinda, you certainly have your share of trouble!” (7). But what distinguishes this potentially eugenic drama from the thoroughly elitist and eugenic writings of most white women birth control and sterilization advocates is its profound sympathy for Mrs. Jasper, along with its awareness of the shortcomings of Miss Shaw’s advice. When Mrs. Jasper wonders “what sin we done that Gawd punish me and Jim lak dis,” Miss Shaw replies: “God is not punishing you, Malinda, you are punishing yourselves by having children every year. . . . You must be careful!” Malinda answers: “Be keerful! Dat’s all you nu’ses say! . . . You got’a be tellin’ me sumpin’ better’n dat, Mis’ Liz’beth!”58 Miss Shaw’s reply gets to the heart of the matter and the title of the play: “I wish to God it were lawful for me to do so! My heart goes out to you poor people that sit in darkness, having, year after year, children that you are physically too weak to bring into the world—children that you are unable not only to educate but even to clothe and feed. Malinda, when I took my oath as nurse, I swore to abide by the laws of the state, and the law forbids my telling you what you have a right to know!” (7). Soon after this exchange, Mrs. Jasper’s heart condition suddenly worsens; she dies, and, as a result, her daughter Lindy realizes that she must abandon her plan of attending Tuskegee in order to take her mother’s place in caring for the rest of the children.

This play’s complex attitudes toward poor and working-class fertility are neither wholly progressive nor wholly elitist. Clearly, poor people’s “troubles” cannot be neatly resolved by birth control, as Miss Shaw’s vague admonition and explanation imply. To paraphrase Dorothy Roberts, there are distinct dangers in promoting reduced reproduction as the means to social justice or economic equality.59 Moreover, like Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, Burrill’s play problematically juxtaposes the standard English diction and unmarried, childless state of the professional Miss Shaw with the dialect and hyperfertility of the working-class Mrs. Jasper, seeming to lend support to Du Bois’s view that “there are to be sure not enough children in the families of the better class.” On the other hand, there is no suggestion in this play that the Jaspers—or the poor in general—are naturally inferior; indeed, Lindy seems clearly on the road to upward mobility as she packs her bag. Unlike Nella Larsen’s “Sary Jones,” Mrs. Jasper does not survive, yet she has an acute awareness of her own plight, along with a desire to change it. With education and family planning, Burrill seems to be arguing, Mrs. Jasper, like all African Americans regardless of class, can be uplifted, can become “New” Negroes; their problems stem from social conditions (including a perverse legal system that prevents the dissemination of birth control information to those who most need it), not their nature.60 Birth control in this context offers a way out of the oppressive burdens of poverty and therefore a way up the social ladder. Indeed, knowledge of birth control corresponds with professional, middleclass status in Burrill’s play: the ability to control female fertility, a commodity already possessed by Miss Shaw, is desperately needed by Mrs. Jasper. As Roberts puts it: “White eugenicists promoted birth control as a way of preserving an oppressive social structure; Blacks promoted birth control as a way of toppling it.”61 Even modern black club women, some of whom were prone to an elitism that could shade into eugenic thinking,62 adopted “Lifting as We Climb” as their motto, connoting a belief in the improvability of all black women; there is no natural inferiority, then, just socially produced inferiority. This is elitist, to be sure, but not hereditarian.

As all the antilynching plays demonstrate, modern African American women knew, if anyone did, that the modern United States was not a meritocracy. Grimké’s Rachel is fundamentally about the inability of the most educated and talented black people to rise professionally to the level of their abilities and the attendant inability of the fittest black people to reproduce happily and successfully. It makes perfect sense that New Negro women writers would not view poverty or racial violence solely as the lot of the unworthy or the naturally inferior.63 Social Darwinism could only be true given prior social, economic, educational, and professional equality; African Americans were quite clear that such equality did not obtain in the modern United States. As I will discuss in the following chapter, New (white) Women birth control advocates and eugenics field workers, by contrast, viewed poverty, feeblemindedness, and tuberculosis, among a host of other conditions, as the natural states of lower-class dysgenic white folks; sterilization was therefore deemed a natural prescription. “Blessed” barrenness and sterility carry a wholly different valence in the writings of modern black women: they are the particular burdens of female blackness, a modern prescription issued by a sick lynching culture.

If not children, then, what can the New Negro woman pass on? In the absence of literal progeny, Grimké and Burrill pass on the tragedies of black motherhood, the drama of an African American family history that includes lynching. Repeatedly, their black women characters choose what to tell and when to do so, thereby intervening in and rewriting what Hortense Spillers calls “an American grammar” founded on the captivity and mutilation of African American men’s and women’s bodies (261–62). In Grimké’s Rachel, Mrs. Loving holds on to her knowledge of the lynching of her second husband and her son from a prior marriage until her children, Rachel and Tom, are themselves of an age when they are likely to be lynched or to begin producing children. In Mary Burrill’s antilynching play Aftermath (1919), plot, suspense, and characterization all flow from the withholding of the truth of lynching by Millie, a young African American woman.64 A “slender brown girl of sixteen,” Millie cannot bear to write to her brother John, who is away at war, about the lynching of their father. John unexpectedly returns home, soon discovers that Millie has been hiding the real reason for their father’s absence, and begs her to reveal the truth, crying, “Come, Millie, for God’s sake don’ keep me in this su’pense!” (90). In response, Millie ends one form of suspense—explaining that “them w’ite devils came in heah an’ dragged him—. . . . They burnt him down by the big gum tree!”—only to create another: the play ends with John’s rushing out of the family cabin to exact revenge on his father’s lynchers. Readers and audiences know that John, too, will surely be lynched, although the ending keeps us nominally “in suspense,” with the son’s lynching perpetually about to be performed.

Contemporary African American women continue to pass on such almost unbearable stories of lynching and infanticide, suspense and barrenness, loving and burning. That is, they are repeatedly relating the repetitive trauma within modern African American history. In her essay “Traumatic Awakenings,” Cathy Caruth revisits Freud’s well-known analysis of a bereaved father’s dream—a dream that awakens him—of his dead child standing by his bed and saying, “Father, don’t you see I’m burning?” As the father is dreaming, the child’s corpse, lying in the next room, has in reality been lit afire by an overturned candle. Caruth argues that both Freud’s analysis of this dream and Lacan’s later revision of that analysis fall short: “The full implications of such a transmission [the dead child’s speaking to the father in his dream] will only be fully grasped, I think, when we come to understand how, through the act of survival, the repeated failure to have seen in time—in itself a pure repetition compulsion—can be transformed by, and transmuted into, the imperative of a speaking that awakens others” (103). Caruth believes that the father’s dream, along with its embedded message from the burning child and the resultant awakening of the father, represents the “ethical burden of . . . survival” (103). Repetitive performance, then, “transmits the ethical imperative of an awakening that has yet to occur” (104). To put this plainly, in the aftermath of traumatic loss, the father bears the burden of awakening, telling, and acting. The difference between the father’s dream and the nightmare of lynching is that the father need not expect the death and burning of his children, or of his children’s children, to occur again and again in his family history. The mothers, sisters, and daughters in Rachel, Aftermath, “For Unborn Children,” Safe, and A Sunday Morning in the South repeatedly do in fact “see in time,” but can do nothing to stop the burning, even though they have been awake all along. As Karla Holloway argues, “For black women, the kind of stress Lacan associates with the unconscious is not buried at all.”65 The “ethical imperative” to be awake and to tell is one that Grimké, Burrill, Livingston, and Douglas Johnson—to be followed by Toni Morrison and Michon Boston and Suzan-Lori Parks66—willingly accept, again and again, as they pass on a story that is, in the final words of Beloved, not to be passed on.