Chapter Five

New White Women

The U.S. Eugenic Family Studies Field Workers, 1910–1918

Committed to Bedford [Bedford Hills New York State Reformatory for Women] from town of Saugerties [N.Y.] on charge of impairing the morals of her children, Sept. 1912. She is a tall, big-boned girl with an abundance of dark brown hair, prominent masculine features, and large, conspicious [sic] teeth, black with tartar. To talk with her in the first days of her stay in Bedford one can get not the slightest idea why she was sent here. She asks frequently if she can go out tomorrow and offers me a crate of berries if I will take her away. . . . She tests 7 years by the Binet. —Notes of V. P. Robinson, eugenics field worker (c. 1914–17)

On account of this mental immaturity he should never have been allowed to become a father. It would have been a great economy for the community to have prevented his feeble-minded and criminalistic brood, by taking him into custody as a boy and keeping him segregated and at farm work all his life long. —Mary Storer Kostir, The Family of Sam Sixty (1916)

Scholars have begun to challenge the notion that the “New Woman” represented a thoroughly socially progressive and feminist icon.1 As quite a few historians have recently observed, nearly all feminist activism of the late 1800s to early 1900s was intertwined with the social purity movement and often with eugenics.2 Literary critic Angelique Richardson argues persuasively that the New Woman, once placed “securely in her historical context,” often emerges as having “perpetuate[d]” the mainstream elitism, gender essentialism, and biological determinism of her day.3 Historian Gail Bederman ably demonstrates that even model New Woman Charlotte Perkins Gilman advanced a “feminism [that] was inextricably rooted in the white supremacism of ‘civilization.’”4 Similarly, Dana Seitler has recently focused on the “coterminous ideologies of feminism and eugenics that [Gilman] engages.”5 Of course, then, as now, activist women occupied a range of political positions—some women reformers advocated what contemporary scholars readily acknowledge to be reactionary, racist, and elitist versions of “social purity”; others promoted what were then quite progressive versions of social and labor reform. Kathryn Kish Sklar suggests that at least some middle-class women reformers of the Progressive Era sometimes “transcended their own class interests.”6 But very few advocated anything resembling contemporary challenges to class, gender, or racial distinctions, and it is perhaps unreasonable to expect them to have done so.7 Indeed, some New Women did not even endorse women’s suffrage.8 Others willingly (and, in some cases, consciously and enthusiastically) established their professional freedom directly on the revocation of the bodily freedom of poor and working-class people.9

The many field workers for the U.S. eugenic family studies of the 1910s and 1920s are compelling, and largely neglected, New (white) Women whose professional and social mobility depended on, indeed could be defined by, the enforced immobilization of others, both women and men.10 The field workers traveled throughout the United States collecting genetically incriminating data about supposedly dysgenic, feebleminded rural white families—data that could then justify the compulsory institutionalization or sterilization of as many family members as possible.11 These workers were newly mobile, college-educated women—some professionals, some volunteers, but all clearly social reformers—even if the objective of their reform was not at all “progressive” according to present-day definitions, or even in comparison with other women’s reform agenda of their day. Unlike more liberal women reformers who were generally committed to the protection and support of poor mothers and children, the eugenics field workers were committed to their confinement or elimination. Despite the appalling nature of their politics, however, the field workers must still be considered New Women. In fact, they are in some ways paradigmatic New Women, whose work demands a new, more precise taxonomy and analysis of the “New Woman” and, indeed, of the “Progressive Era” in general.12 More reactionary paternalists than progressive maternalists,13 the eugenics field workers help buttress the view that the 1910s and 1920s were an era of radical, but sometimes quite regressive and dangerous, reform enacted by women.

Cultural historians have in the past decade generally relied on the concepts of maternalism and professionalization to describe women’s activism of the 1910s and 1920s, but the field workers’ explicit project—to protect the nation’s germplasm by institutionalizing and sterilizing dysgenic poor and working-class women and men—cannot be fully accounted for by either model. Scholars acknowledge that even the more socially progressive reformers, such as the settlement house workers, also benefited from constraints (albeit lesser ones) on others—generally immigrants, migrants, the poor, and the working class.14 To explain this phenomenon, scholars have begun to focus on the problematic maternalism of many professional women reformers between 1890 and 1920, arguing that to promote social welfare policies founded on an idealization of bourgeois motherhood was also effectively to consign other, poorer women to more restrictive, and generally quite unrealistic, gender roles.15 As Robyn Muncy observes, “In an era when constructions of gender would certainly not allow women any authority over men, those women who did gain authority wielded it over other women, and in many cases, used it not to liberate but to restrict their sisters” (122).16 Thus the “female dominion” that historians agree was instrumental in the creation of the welfare state ironically enough rendered many women even less free to pursue activities outside the private, domestic sphere. It was for the sake of their own professionalization that women reformers relied on a maternalism that did not always serve the interests of other women. As Muncy points out, “turn-of-the-century women searching for professional niches” soon realized “that their male counterparts were much more willing to cede professional territory, to acknowledge the female right to expertise in instances where women and children were the only clients” (xv). But because women and children were not their “only clients”—and because many were volunteers—the eugenics field workers complicate the maternalist-professionalization model. The field workers collected data on and exerted power over men as well as women. That expanded clientele in turn permitted them to exceed the feminine, domestic sphere and to participate in the period’s emergent and shifting discourses surrounding labor, social science, and medicine—that is, the “male dominion.”

It was also in part because of their reactionary politics that the eugenics field workers were able not only to enter the male dominion but also to sidestep, at least to a degree,17 the tangled interplay of professionalism and maternalism that plagued their more progressive sisters in reform. The idea that progressive women reformers had to finesse conflict between their professional ambitions and their often egalitarian ideals has become a focal point, indeed a commonplace, in much recent feminist scholarship concerning the reform era. As Muncy vividly puts it, even the most progressive reformers were “encouraged to blame their nonprofessional sisters for all children’s ills” and “to shorten the leash that tied most women to home and children” (xv).18 The eugenics field workers, by contrast, did not seek to protect poor women and their children or to level class differences; their aim was to protect the middle and upper classes from overpropagation by poor, nonproductive, and feebleminded men and women, as well as to maintain class differences. Therefore, unlike the socially progressive women reformers, the eugenics field workers occupied a “professional niche” quite compatible with their reform ideals; unhampered by social progressiveness, they were free to pursue their reactionary work apparently without ideological conflict between politics and profession.19

THE FIELD WORKERS’ primary work was the collection of data for the white family studies that formed the rhetorical and scientific centerpiece of the mainline, conservative eugenics movement in the United States during the 1910s and 1920s (the most famous such study was Henry Herbert Goddard’s 1912 The Kallikak Family).20 While most of the directors and credited authors of these studies were men—usually sociologists and physicians affiliated with the United States Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, the foremost eugenics institution in the nation in the 1910s and 1920s—the vast majority of the field workers who collected the data were college-educated women trained in biology, sociology, or social work. These field workers, all of whom were white, identified and documented the feebleminded members of supposedly inbred, generally rural, poor or working-class, usually white families—with the ultimate goal of reducing the families’ fertility by institutionalization and sterilization. Occasionally, some families or family members in the studies are described as being of mixed race (as in Arthur Estabrook’s 1926 study, Mongrel Virginians) or as having “bred” with other races. The studies invariably treated both whites’ willingness to breed with other races as well as the resultant racial hybridity as a priori evidence of the families’ genetic inferiority. But the organizers of the studies for the most part did not worry very much about the nonwhite dysgenic; for the eugenicists associated with the Eugenics Record Office (ERO), there was no urgency to establish the lesser genetic quality of nonwhite Americans, particularly black Americans. Their brand of eugenics took white supremacy as a given; they therefore concentrated on establishing, rather than an interracial hierarchy, an intraracial one. Indeed, the overall project of the family studies can be seen as a refinement and purification of a white Americanness so thoroughly parsed that “Scotch-English blood” generally occupied the top tier.21

Sociologist and historian Nicole Rafter has identified fifteen such studies of rural, predominantly white families that were published in the United States between 1877 and 1926. James Trent points out that a family study was published as late as 1936.22 Many of the studies were written for a lay audience; several of them became best sellers. The most widely read of the studies and the ones that remain the best-known today are Robert Dugdale’s The Jukes (1877), which was the first in the genre, Henry Herbert Goddard’s The Kallikak Family (1912), and Arthur Estabrook’s Mongrel Virginians: The Win Tribe (1926). But the published studies represent only a small fraction of the total number of studies conducted. Rafter’s 1988 book, White Trash, as important and insightful as it is, does not take into account the hundreds of additional, unpublished studies of “defective” families conducted by the ERO between 1910 and 1918, with the peak of family study research and publication occurring between 1915 and 1917. Both the timing and the sheer number of the studies testify to the urgent, overdetermined nature of their mission—one that could be bluntly summed up as “think nationally, sterilize locally.”

A wide range of political, economic, and social circumstances converged to create a national climate congenial for the widespread study of dysgenic U.S. families in the 1910s and 1920s. Eugenic discourse, with the family studies as its distinctive genre, accommodated and recorded collective U.S. class and racial anxieties resulting from World War I, unrest among colonized peoples, class rebellion and revolution, labor organization and unionism, suffragist activism and militancy, the fluctuation of national and racial boundaries, widespread immigration and migration, urbanization, industrialization, and economic uncertainty (the eugenics movement in the United States was, in a sense, bracketed by the depression of 1893 and the Great Depression).23 Indeed, a crucial, but underemphasized, context for the rise of eugenics in the United States was the prevailing national perception that a new, increasingly global form of economy had arisen—one that required new, more competitive kinds of American labor and of American laborers and their management.

Scholars’ recent reliance on maternalist and progressiveness-versus-professionalization models to understand the reform era has led both to the relative neglect of such broader (though still gendered) class and labor issues embedded in the U.S. eugenics movement and to the marginalization of reactionary (professional and volunteer) women reformers like the eugenics field workers. Granted, the family studies in particular, as well as eugenic discourse in general, call—and call loudly—for both the feminist and the new historical critical perspectives that underlie the maternalist and professionalization models.24 First, the field workers were limited both professionally and personally by the period’s restrictive notions of gender; women simply did not have equal access to, or equal power within, male-dominated professions. As Rafter succinctly puts it, because the field workers were permitted to collect data but rarely to function as directors or authors, the family studies were “simultaneously advancing and segregating women in science.”25 Second, the disciplinary aspects of the studies’ aims—diagnosis, involuntary institutionalization, and compulsory sterilization—are clear, as is eugenics’s imbrication with the period’s professionalization of medicine and the social sciences. Rafter has argued persuasively that the eugenic family studies “promised to further the interests of an emergent professional class,” including the college-educated white women who made up the vast majority of the studies’ field workers.26 But neither a professionalization–new historical paradigm nor a maternalist-feminist one, nor their combination, can fully account for the field workers, or for the content and conduct of the eugenic family studies of the 1910s and 1920s.

To begin with, the studies’ conservative, hereditarian eugenics effectively derailed a thoroughgoing maternalism. With nature favored over nurture in explanations of human behavior, fathers attain a (genetic) status equal to that of mothers. Just so, while the ERO and its field workers certainly worried about the sexuality and potential maternity of feebleminded and immoral women, they worried as well about the sexuality and potential paternity of feebleminded, criminal, and destitute men. Thus, Shawn Michelle Wallace’s compelling insight that “racialized discourses in the postbellum era situated white middle-class mothers at the locus of biological inheritance”27 is only partly valid; the class-based, intraracial eugenics typical of the 1910s and 1920s sought both to encourage middle-class women to select carefully the fathers of their children and to discourage the fertility of dysgenic lower-class women and men. First, as eugenics historian Mark Haller has shown, just as many men as women were compulsorily sterilized for eugenic reasons in the United States between 1909 and 1930; in some states, more men than women were sterilized in this period.28 And it perhaps goes without saying that these procedures were performed predominantly on the incarcerated and on the poor and the working class.29 Second, the studies were not conducted solely by professionals. During the 1910s and 1920s, many “volunteer collaborators,” lacking a direct professional stake in the matter, willingly submitted to the ERO documentation of the feebleminded in their communities. Finally, the emergence of new forms of labor control and methods of production (especially scientific management and the assembly line in the 1910s, at precisely the same time that family study activity reached its peak) represents a crucial historical and economic context for understanding the extraordinary pervasiveness of eugenic thinking during the reform era. Efficiency became a byword both in production and reproduction in the United States in the 1910s and 1920s, and the family studies appeared to hold the promise of increasing America’s economic and human efficiency. As Calvin Coolidge put it in his 1925 inaugural address: “The very stability of our society rests upon production and conservation.”30

Most eugenics advocates, regardless of their political orientation, acknowledged that “positive eugenics,” the promotion of births among the genetically desirable (generally from the middle/professional classes), had to remain voluntary, even purely theoretical.31 But “negative eugenics,” the prevention of births among those designated genetically toxic (generally from the poor and the working class), was not only widely endorsed but also actively practiced in the United States as early as the 1870s and 1880s, even before the term “eugenics” entered common parlance.32 While the endorsement of negative eugenics was widespread among reformers of the day across the political spectrum of the United States, the eugenics field workers, both professionals and volunteers, were unique in their central role, as women, in the enactment of negative eugenic practices on poor and working-class women and men. This activist role, however unsavory, played by some New Women suggests that we must attend more closely to the complex economic and social patterns of the reform era in general and of the U.S. eugenics movement in particular.

THE EUGENICISTS responsible for the ERO’s family studies—both male supervisors and female field workers—certainly had motivations beyond what Rafter terms “professional self-interest.”33 They truly believed in the scientific, national, social, political, and economic righteousness of their work; they considered themselves reformers, even progressives—not that they would be seen as such today. In their promotional materials, U.S. eugenics organizations often referred to eugenics as a charity that would end charities.34 Not surprisingly, many well-to-do Americans, professionals and nonprofessionals alike, responded favorably to such rhetorical tactics. Eugenics activities in the United States during the 1910s and 1920s (including the family studies, as well as the passage of state compulsory sterilization statutes) were made possible by a collaboration between members of the middle/ professional/managerial class and members of the upper/wealthy/ entrepreneurial class. What Jeffrey Weeks has said of the eugenics movement in Britain can thus be applied to the U.S. movement as well: “There is undoubtedly an emphasis in eugenics on the social importance of the middle-class expert. . . . But we cannot explain eugenics simply in these class reductionist terms, because though eugenics ideas may have had a class-specific origin, they were presented as a strategy for the whole ruling class to adopt, and support was gained from outside the professional classes, just as opposition to eugenics came from within it.”35 For example, the Eugenics Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor was founded in 1910 by Charles Davenport, holder of a Ph.D. in zoology and perhaps the nation’s most prominent eugenicist, with funding from Mary Harriman, widow of the railroad tycoon E. H. Harriman. John D. Rockefeller and the Carnegie Institution were early ERO sponsors as well.36 That such a synergistic, cross-class private collaboration would have public policy effects was, perhaps, inevitable.

The ERO, under the supervision of founder-director Charles Davenport and superintendent Harry Laughlin, developed an ingenious method for insinuating its privately funded eugenic ideology into the state apparatus. First, the ERO trained eugenics field workers during annual summer courses, conducted between 1910 and 1924. Some workers were then sent out across the country to conduct field work directly for the ERO by collecting data for the family studies or by administering “fitter family” contests at state and county fairs.37 The rest were assigned to various state institutions such as mental hospitals, colonies for the epileptic and feebleminded, reformatories for juvenile male criminals, and homes for delinquent girls. The ERO agreed to pay the institutional field workers’ salaries for a year, during which time only the workers’ “expenses [were to be] paid by various States.”38 The ERO hoped that, after the initial year, the institutions would voluntarily add the eugenics field workers to their payroll.39 In the 1910s, at least half of the institutions did in fact elect to keep the workers on staff. The Eugenical News, a bulletin published by the ERO for its staff and field workers, regularly published news of such permanent appointments of the field workers by the state institutions where they had been installed for the one-year “introductory trials.”40 Individual professional ambition was certainly being served by such a policy—at the same time, widely held, but nonetheless private, eugenic beliefs were also being publicized, institutionalized, and nationalized.

There was significant nonprofessional participation in the U.S. family studies as well. Hundreds of “volunteer collaborators” obtained family study kits from the ERO that included “Brief Instructions on How to Make a Eugenical Study of a Family,” along with “family pedigree charts” and “individual [genetic trait] analysis” cards.41 Private citizen-volunteers sometimes submitted information about eugenic families known to them (usually their own); but most submitted to the ERO unsolicited, informal assessments of the dysgenic in their communities, as is shown by a letter from Ida M. Mellen to Harry Laughlin, superintendent of the ERO, written in 1912: “I have been trying for some months to find out just why the child of my charwoman is feebleminded,—aside from the obvious fact that the woman herself is ‘cracked’ on religion. By getting one fact at a time I have finally drawn out about all that seems possible, and herewith enclose you the account and chart. I do not know that it is worth anything, but send it in any event, for, in a general way, it shows a relationship between religious insanity, violent temper &c., and feeblemindedness.”42 This letter attests to the class dialectic engendered by the family studies, a dialectic more complex than a professionalization model allows. Ida Mellen had attended the ERO summer course in 1912, but she did not become a field worker (she became secretary of the New York Aquarium) and therefore would not reap direct professional benefits from the data she submitted

Field worker training at the Eugenics Record Office, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 1910s. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

about her feebleminded maid.43 The letter provides clear evidence of the complex and disturbing interclass (as well as intragender) politics of the conservative eugenics movement in the United States. Quite a few women and men of the middle and upper classes volunteered to expose and document the feebleminded who worked in their homes or lived in their communities. During the 1910s, as many “volunteer collaborators” as professional field workers submitted information to the ERO about what they perceived to be the often alarming genetic makeup of American families.44

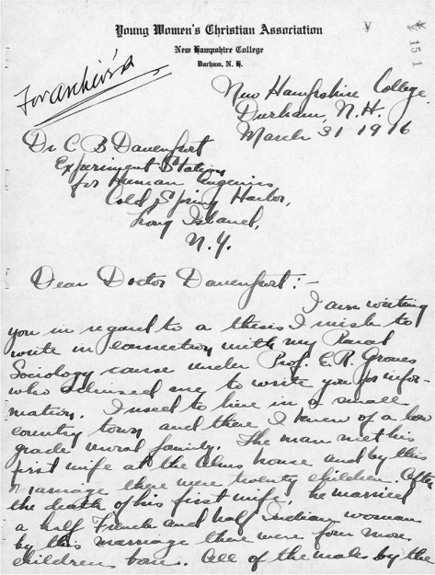

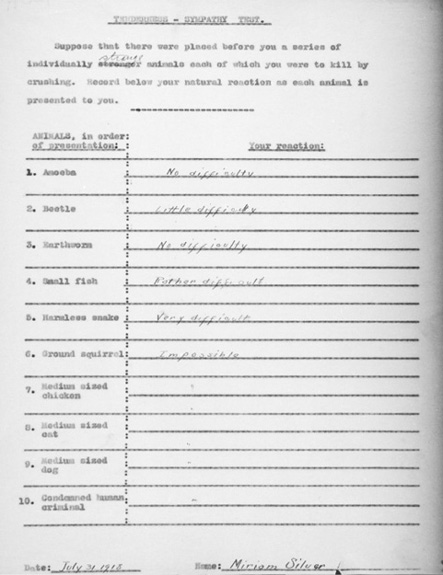

Granted, the professionalization model does work to the extent that the professional field workers’ individual careers were obviously being advanced by the family studies. Some of the workers’ ambitions were even quite explicitly established on the backs of the “feebleminded”—most often those whom they knew personally. Bernice Reed, a volunteer collaborator attending New Hampshire College with hopes of a professional future, wrote to Charles Davenport in 1916 about her knowledge of “a low grade rural family” in the “small country town” in New Hampshire where she “used to live.” According to Reed, the males in the family “have either been in reform school, prison or have been arrested at various times.” “The females,” she writes, “are all of a very low moral grade[,] nearly all of them being prostitutes at one time or another.” “The children,” she adds, “have been able to go only to a certain grade in school and are unable to make further progress.” Reed concludes her letter by asking Davenport, “Will you please tell me how to go to work in making my thesis?”45 Davenport encouraged Reed to send him her completed thesis, a family study she titled—using a pseudonym—“The Trix Family.”46 Reed resisted divulging the family’s real name for reasons explained in a letter to Davenport accompanying the study: “Public opinion and the writer’s personal acquaintance has to be relied upon to a great extent and much truth can be gained in this way as such people do not hesitate in telling their family and private affairs” (3). When Davenport nevertheless pressures her to reveal the family’s real name, Reed demurs: “I would be glad to send the real names if they would be held in confidence at the station and would not get back to the state as it might cause me some trouble for I had to compile my data very carefully.”47 She receives prompt reassurance from Davenport: “In case you send the names, as I trust, we will mark the copy ‘extra confidential. No names to be divulged to State Agents.’”48 Clearly, Reed aims to establish a professional life far from her rural New Hampshire roots, while using her knowledge of the town’s illegitimacy in order to lend legitimacy to her own professional status as researcher. But her real genius lies in her self-referential conclusion to “The Trix Family”: “Someone must be held responsible, and it is the state’s duty to assume responsibility. In the first place there should be a census taken yearly or oftener of the school children, and a test applied in order to determine each pupil’s mentality. This work should be done by expert workers employed by the state” (17). More significant than Reed’s self-promotion here (which could be subsumed under a conventional professionalization model) is her insistence on “the state’s duty”—the institutionalization and nationalization of a conservative eugenics platform thus comes to the fore even within an individual volunteer worker’s conclusion of her family study. Again, the aims of the family studies and the field workers are far broader than individual professionalization, reflecting and inscribing national anxieties regarding modern social formations and preoccupations as various (though also clearly connected) as morality, intelligence, ethnicity, urbanization, productivity, competitiveness, labor, and gender.

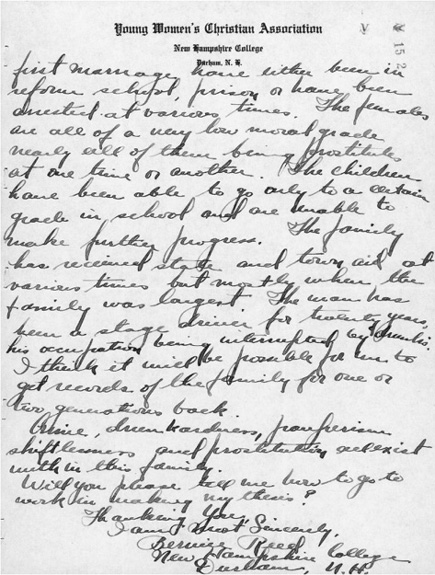

BERNICE REED WAS on the right track in her networking with Davenport. Although, as Nicole Rafter has observed, women were rarely the credited authors of published family studies, the male eugenicists at the ERO actively recruited them to become field workers. Superintendent Harry Laughlin conducted summer classes in field work at Cold Spring Harbor from 1910 to 1924—classes aimed specifically at college women. Of the 258 field workers trained, 219 were women.49 At the peak of the ERO’s family study activity, from about 1915 to 1917, at least 90 professional field workers were actively collecting and recording an enormous amount of data regarding families from at least 22 states; of these more than 90 workers, at least 80 were women.50 A pamphlet included in the ERO’s 1912 summer training course, “Directions for the Guidance of Field Workers,” suggests some of the reasons the male eugenicists of the 1910s sought female field workers: “First of all, unfailing courtesy and regard for and sympathetic (humanistic) attitude toward the persons you are interviewing are essential. . . . To get the truth requires great tact.”51 The field workers were being selected, then, according to stereotypical feminine criteria; among the field worker evaluation instruments, there was even a “tenderness-sympathy test.” In other words, the feebleminded women were not the only women being studied within the context of the family studies. In this instance, the field workers were clearly experiencing the period’s gender restrictions, just as the period’s more liberal women reformers did.

The role of the social scientific field worker, like the role of the settlement house worker or social worker, did represent a new professional alternative for middle-class, college-educated women (and one less conflicted between profession and politics), but clearly there was a catch. As Robyn Muncy puts it, if women “donned the behavioral garb appropriate to professional life, they invited criticism for being un-feminine,” but “if they refused to wear the suit, they lost the aura of professional authority” (xiii). “Qualities Desired in a Eugenical Field Worker,” a list prepared by Harry Laughlin in 1921, illustrates the quandary faced by the field workers. According to Laughlin, the ideal field worker would possess the positive stereotypical feminine traits—including “Industry,” “Loyalty,” “Social ability,” “Obedience”—yet lack the negative ones—such as “Gossip” and an absence of “Analytic” ability.52 Moreover, not only were the field workers expected to exploit their positive womanly attributes (industry, courtesy, tenderness, and so on), they were, as data collectors for the studies, also being replaced rather firmly within the context of the “family,” however dysgenic that family might be. Finally, like the newly professionalizing nurses of the same period, the eugenics field workers were assigned strictly limited duties by their male superiors. Dr. Davenport, director of the ERO, advised them during a summer 1915 field worker meeting: “Do not diagnose. Let the one studying the history diagnose, but make the case history complete so that diagnosis will be possible.”53 The ERO doctors and sociologists ranked analytic skills well below interpersonal skills for effective field work (in fact, they ranked number ten on the list of thirteen desirable field worker traits).

The male eugenicists were probably correct that courtesy and tact would be essential prerequisites for such work. The field workers traveled to generally rural study sites throughout the country, where they conducted interviews of family members and their neighbors, acquaintances, pastors, and physicians—taking notes all the while. The workers then recorded their own observations of dysgenic family members’ abilities and behaviors—all with the aim of documenting the genetic unworthiness of their subjects. Apparently, the field workers’ tested-and-proven “tenderness and sympathy” usually did work to elicit a great deal of genetically incriminating information, if not from the family members themselves, then from those who knew them. One field worker described her methodology in this way: “[Only] those all agreed were feebleminded were listed [as such]. In this way at least four persons passed [judgment] upon each family reported, which served to verify [their feeblemindedness when] . . . these people could not be

Letter from a volunteer collaborator to Eugenics Record Office director Charles Davenport, March 1916. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

“Tenderness-Sympathy Test” administered to field workers in training during the 1910s and 1920s. Courtesy of Harry H. Laughlin Collection, Pickler Memorial Library, Truman State University, Kirksville MO 63501.

visited personally.”54 Clearly, then, despite Dr. Davenport’s admonishment not to diagnose, the field workers frequently used whatever information they could get, from any source, to establish dysgenic diagnoses of the families they encountered.55

Sadie Devitt, ERO class of 1910, studied several rural Minnesota families and was one of the most successful and prolific data collectors as well as one of the most evocative and creative writers among the field workers. Her unpublished 1917 notes about a family in southeastern Minnesota, titled “Timber Rats” (the local nickname used for the family), demonstrate her remarkable narrative—as well as ideological—agility:

My first introduction to these people happened thus—It was a hot, summer’s day and we had driven from Preston to Whalan. At Whalan we found that the man I wished to see lived farther down the ravine. The road lead [sic] up for a ways and then we began going down and down. In reality we went down but about 200 feet but the horses had to seemingly sit down and slide over rocks most of the way so it seemed much farther. Then we drove along the rocky road at the foot of the ravine. . . .

Soon we met a wagon, drawn by one bony horse. The driver was a boy of about 17 years, with all the earmarks of a mental defective. Thinking he might be acquainted with the inhabitants of the valley I asked him if he could tell me where Hawkin Hawkinson lived. The answer came in one of the slowest drawls I’ve ever heard, “He-e don’t live here no more.” “Has he moved?” I asked. “Yes, he’s moved, he’s dead,” came the answer.

“Oh Lord!” my driver shouted and burst into convulsions of laughter. The boy drove on, wondering what had happened to the driver that he laughed. I have a suspicion that I smiled. However, I warned my driver he must be more careful next time, for no one’s feelings could be hurt. . . .

That day, in that sparcely [sic] settled ravine, I saw at least five feebleminded people so another trip, for more extensive study was planned. . . .

The first family visited was that of Halvor Hagen, an uncle who had married his own neice [sic].”

Devitt, apparently struggling to maintain her “courtesy and regard for and sympathetic (humanistic) attitude toward” the family, tracks down the niece who had married her own uncle and describes their encounter:

She is a feebleminded woman, of the moron type; who can neither read nor write. She is very slovenly in her appearance and neglects her home. . . .

Upon my return from visiting this family, I asked one of the citizens of Peterson how they came to allow such conditions to exist in their community. He said, “People don’t bother about that bunch for they are nothing but a lot of ‘timber rats.’”56

Devitt takes up the term, and she encounters a number of families in the region that she labels “timber rats”—so named for their means of survival in rural Minnesota in 1917: timber cutting, along with hunting and subsistence farming.

But the field workers’ travels were not always so arduous as Devitt’s. Sadie Myers, a volunteer worker in rural Utah in 1916, described in lively third-person narration, in another unpublished work, her data collection style: “As soon as the field secretary finished her work in one town, she usually took an automobile in order to save time, and in this way was able to make as many as three towns in one day.”57 Though her travels are easier than Devitt’s, Myers finds similarly appalling dysgenic families in her chosen region (three rural Utah counties): “Frequent cases of goitre were noticed,” she writes, and “in one small community three separate families of Cretins were found.” She also finds “incest and illegitimacy running rampant,” with many feebleminded children the result. She visits local schools in order to confirm this widespread feeblemindedness among the counties’ children, and she describes one particularly trying day: “While testing in one of the schools, the field worker was much annoyed by the janitress who kept dropping the mop and stumbling over the seats.” But overall, Myers seems quite upbeat about her job; it was not all about facing feeblemindedness in the field: “Many of the women’s clubs [in the area],” she reports, “invited the field secretaries to speak to them and all showed great interest in the work.”

The potentially feminist, intraclass, intergender politics of both Myers’s and Devitt’s studies (and of other unpublished studies) are certainly worth noting. First, both field workers have clearly wrested the power of diagnosis from their male supervisors. They readily note the “mental defectives” they encounter: the “feebleminded,” the “moronic,” the “Cretins.” Indeed, the women come across in their field notes as experts hard at work in an exciting field. But, with a salary of $600 a year in 1916, plus the requirement of frequent progress reports to the ERO, the women did not possess wide-ranging professional or economic freedom (Harry Laughlin’s salary that same year was $3,600).58 At the same time, the field workers’ ability to seize diagnostic power was limited by the ideological imperatives of their male supervisors and of eugenics itself.

The workers’ diagnoses would be permitted to stand only if they served to bolster the aims of the movement as a whole. The workers actually appear at times to be aware of eugenic ideology’s power to limit their revision of the studies’ conduct as well as any challenge of the eugenical “truth” they had been selected to “get.” For example, a Miss Kendig, a field worker assigned to study delinquent girls at Monson State Hospital in New Jersey, reported at a 1913 Field Workers Conference: “I was rather horrified that I was getting no results from the standpoint of heredity. There was no epilepsy, no feeble mindedness and no one became insane. I began to feel as if I had been careless. Even tho [sic] I tried to double my care I could not reproduce the same number of defectives that I had in adult cases. . . . There is a great danger of snap judgments. I want to avoid it. We must strive against premature publishing. The Binet tests should be given to all the members of the family and see if there are stigmata of degeneration.”59 No one at the conference takes up Kendig’s call for caution or careful testing; indeed, she is followed in discussion by a Miss Robinson, who asks, “What is the best avenue of approach to a family [of a delinquent girl] to get results? Our best entrance,” she decides, “is as a friend of the girl” (47).60

This remarkable moment in the field workers’ conference proceedings leads us away from their intraclass, intergender feminism and toward their interclass, intragender politics—which, as it turns out, are far less progressive. In the case of Robinson’s remarks, the field worker is decidedly not a “friend of the girl,” whom the worker is likely seeking to have compulsorily institutionalized or sterilized. The conduct and content of the studies depend on a dialectic of eugenic/college-educated/professional female field worker versus dysgenic/feebleminded/working-class family member. Occasionally, however, and perhaps not surprisingly, the field workers encountered resistance, as was reported by Lucile Field Woodward at the 1913 conference: “My work is with epileptics in New Jersey. . . . There is one town [there] made up almost entirely of mulattoes. They think the information I am trying to get is to be used against the Negro race. The children all go to one school. There are no children in the school who are not mulattoes. The teacher was also a member of this family. She has heard lectures on eugenics. She . . . said [to me], ‘I am proud of my ancestors and I do not care to give information against them’” (42). Here, Woodward recognizes the teacher’s overt resistance as “Negro” solidarity, although the teacher, if “mulatto,” has both white and black ancestors. The field workers frequently had trouble not only interpreting but also simply perceiving less overt acts of resistance. Even the possibility of more subtle, class-based forms of resistance seems not to have registered with the workers. Like Ida M. Mellen’s “charwoman,” Sadie Myers’s “janitress” can only be a stumbling, feebleminded sort—an inefficient, and thus dysgenic, working-class woman. Study subjects may either ease or hinder the investigation, but they can never function as agents for their own genetic vindication. Perhaps most chilling are the multiple instances in which inmates of state institutions have been called on to type up field workers’ notes. In 1914, volunteer collaborator Dorothy Gardner submitted a case history on a patient “who was in the New Jersey State Hospital from Nov. 19, 1913 to Jan. 9, 1914,” noting in longhand on the cover sheet that the report was “typewritten by a patient of the N.J.S.H.”61 Here, the institutionalized are literally inscribing, with the tools of modern record keeping, if not their own confinement, then the confinement of other study subjects much like them.

Feebleminded women were being placed in custodial care for eugenic reasons as early as 1878—not coincidentally, just as the New Woman was emerging. Although they established a new professional role for women, the family studies (along with mainline eugenics in general) also constituted part of a cultural backlash against the period’s feminist activism and against the idea of sexually, or politically or professionally, liberated women. Such a typically eugenic measure (one advocated by all of the studies and all of the field workers) as the institutionalization of feebleminded women stands, then, as a modern adaptation of long-used strategies for curbing women’s socially subversive behavior.62 As the following excerpts from two studies (among the few published family studies written or coauthored by women field workers) disclose, “feeblemindedness” attains identity with socially undesirable (often sexual) behavior by women, almost always in the absence of any “Binet tests” to establish their “stigmata”:

III 15 [genealogical code] is probably feebleminded. She appears of average intelligence, for she is sharp-tongued and voluble.63

A daughter [in the family] . . . has an uncontrollable temper and is subject to hysterical spells. Can read and write and has a fairly large vocabulary. Is dull of comprehension. Contrary and complaining, is probably on the borderline of feebleminded.64

Repeatedly, the field workers note the women’s “immorality,” their “slovenliness,” their failure to take good care of their homes and children. Here, the family studies do seem to be partaking of, and promoting, maternalism, with its values of female nurturance, higher morality, and dependency. Certainly the studies and the field workers tautologically interpret women’s failure to embrace appropriate, bourgeois feminine and maternal behaviors as a sign of feeblemindedness, and feeblemindedness itself as a sign of a proclivity toward such unacceptable behaviors. Unlike the progressive maternalists, however, the field workers are less concerned with the effect of feebleminded mothers and fathers on the welfare of the nation’s children than they are with the effect of such parents, along with their children, on the nation’s genetic makeup. The family studies do not aim to improve poor and feebleminded children’s lives so much as they aim to prevent them. Such final solutions do not fit comfortably under the rubric of “maternalism.”

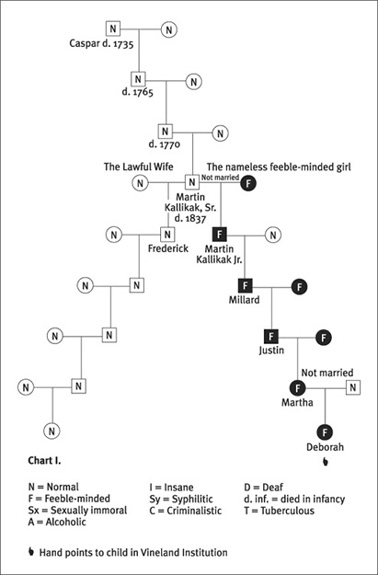

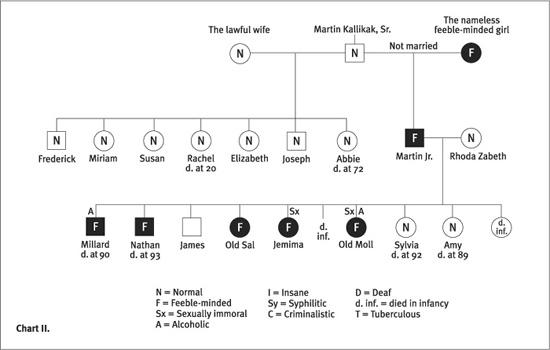

Ironically, the eugenics field worker herself is, to a degree, contained by the gendered national eugenics program she is helping to enact. The workers, too, have been “tested” for their adherence to acceptable standards of femininity—it is just that they have already passed a “tenderness-sympathy” (and eugenics) test that their subjects are presumed, always already, to have failed. In one of the most famous family studies, Mongrel Virginians: The Win Tribe (1926), one of its male coauthors, Arthur Estabrook (who had been one of the few male field workers, but who later became a successful study director and author), sums up the role and status of the field worker when he cites, in a single prefatory sentence, “the highly efficient college women who assisted in the field work” and “must remain unnamed.”65 The anonymous eugenics field worker thus represents a counterpart to the anonymous dysgenic mother; both sets of women—the field workers and the feebleminded mothers—are functionally responsible, indeed necessary, for the production of the family studies—even as they remain “unnamed” or pseudonymous. For example, “the nameless feeble-minded girl” in Henry Goddard’s famous family study The Kallikak Family (1912), who mothered the “kakos,” or the genetically bad/ugly line of the Kallikak family, has her eugenic counterpart in Goddard’s field worker, Elizabeth Kite, who collected the data for the study.66 The women of the Kallikak, Timber Rat, and other feebleminded families produce dysgenic progeny; the field workers in turn replicate those offspring in the form of the study data. Thus dysgenic mothers and female eugenics field workers together are accountable for the production and for the narrative reproduction of a contaminated lineage. To put this another way, the field workers laboriously produce exhaustive catalogs of family members in a metaphorical replay of the reproductive labors of the fertile women of the family. Eugenical News regularly published the number of pages of family study data that had been submitted each month by the field workers, setting up a kind of productivity competition among them:

Miss Helen Martin has reported 59 pages of single spaced notes, equivalent to somewhat over 100 pages of the usual double spaced form, collected mostly in Brooklyn, N.Y.

Miss Edith Douglass has sent in 23 pages of data, about half of which is single spaced, collected chiefly in Hartford, Conn., and vicinity.67

The workers’ productivity is always thoroughly entangled with the reproductivity of their dysgenic subjects. The field workers represent, as educated professionals, New Women (in stark contrast to the dysgenic women they observe); but their own work serves, in part, to re-contain them, as well as their subjects, on the grounds of parenthood.

That re-containment represents potential common ground between the field workers and their more liberal counterparts. Indeed, gender restrictions limited the professional options for reactionary New Women just as much as for progressive New Women, yet contemporary scholars of the New Woman and the reform era have not included the field workers in their studies. Granted, the field workers’ conscious, willing, and active restriction of others by gender and class distinguishes them from the period’s socially progressive reformers, and it perhaps renders them discomfiting exemplars of New Womanhood. Yet despite the fact that the field workers (unlike the settlement house workers) found that their social and political thinking meshed well with the nature of their work, they often found it just as difficult to reconcile their professional ambitions with their personal lives; the field workers, too, had to confront and cope with the period’s prevailing gender roles. On the one hand, the field workers were quite conscious of—and defended—their professional status, as in the following excerpt from the 1913 summer field worker conference proceedings:

Miss Brown;—Every field worker has a feeling of rebellion at being called a field worker. . . .

Miss Ruth Moxcey;—. . . The name of “field worker” is a silly term especially as it is confused so much with the name of “social worker.” It sounds amateur, trivial. I wish you too would bring it up at the Conference and see if they will change it. It is bad enough in the United States to be mistaken for an agriculturalist. (42–43)

On the other hand, the field workers, like many of their more progressive counterparts in the reform movement, were also reinforcing and enforcing some decidedly old-fashioned forms of womanhood and motherhood—certainly for their study subjects, and often even for themselves. For example, several of the field workers ended up marrying physicians and administrators at the institutions where they worked. The Eugenical News kept track of these and other blessed eugenic events—thereby setting up a reproductivity competition, both in addition to and in contradiction of, the productivity competition (regarding pages of data submitted), as in the April 1917 issue:

Mrs. Alan Finlayson, née Anna Wendt [a field worker], ’12 [the year that she took the summer course at the ERO], is the mother of a son, Malcolm Wendt, born January 24, 1917. On March 13 Mrs. Finlayson reported that the boy was growing splendidly and so far as temperamental traits were concerned she could diagnose only “hunger and a fondness for attention” as extraordinarily striking.

The engagement of Miss Edith Atwood, ’14, to Dr. Ralph E. Davis, one of the physicians at the Southeastern Hospital for the Insane, Cragmont, Madison, Indiana, is announced.68

These announcements must be understood in the context of longstanding concerns that college education and professional work for women led them to marry in smaller numbers and to have fewer children

Genealogical charts tracing feeblemindedness and normalcy in Martin Kallikak’s two lineages, one descended from a “nameless feeble-minded girl,” the other from “the lawful wife.” The charts appeared in the most famous family study, The Kallikak Family (1912) by Henry Herbert Goddard.

—a decidedly un-eugenic state of affairs. “The Fecundity of College Women” was a recurring feature in the Eugenical News. Field workers contended, in sometimes contradictory ways, with this notion, as the following excerpt from the October 1916 Eugenical News attests:

Fecundity of Collegians

“College Women as Wives and Mothers” by Miss Laura E. Lockwood of Wellesley in “School and Society” March, 1916, is a reply to the article by Prof. Roswell Johnson and Miss Stutzman in the “Journal of Heredity” based on the low marriage rate and fecundity of graduates of women’s colleges. Miss Lockwood adduces interesting testimony on the strength of the maternal instinct in college students. College life tends indeed to advance ideals of women’s work in the world to a point where they conflict with subordination to humdrum family life and the prosaic physiological processes of child-bearing and the cares of child rearing. Still the charge of inducing decreased fecundity can not be laid solely to the higher education of women. Collegian education in either sex appears to be a deterrent from the family ideal.69

The field workers easily endorsed and disseminated “negative eugenics”—that is, the curbing of the fertility of the genetically undesirable. But “positive eugenics”—promoting breeding among the genetically desirable—was troublesome for them. They had already been established as eugenic and should therefore breed—and breed a lot. Indeed, as historian Amy Sue Bix has shown, ERO director Charles Davenport explicitly wished to avoid hiring single women “as long-term workers,” because he believed they “would serve society better by producing children” (636). Yet having many children would rule out continuing their field work (and thus maintaining their New Woman status), which would nevertheless quite clearly serve to protect and improve the nation’s genetic quality. For Davenport, Bix points out, the solution seemed to lie in short-term employment of women in their reproductive years (636), an interesting inversion of the compulsory institutionalization of dysgenic women during their reproductive years.

Fortunately for aspiring professional field workers, the male eugenicists continued to rely on the skills and perceptiveness of college-educated women, especially in the late 1910s as family study activity peaked and as their criteria for mental normalcy simultaneously became more stringent. After 1929 and throughout the Depression, the ERO and other U.S. eugenics organizations suffered from lack of funds; as a result, the number of ongoing family studies dwindled, but volunteer women field workers (if not so many professionals) remained in demand. Harry Laughlin, in response to an inquiry from Kathryn Stein of the zoology department at Mount Holyoke, wrote to her in 1931: “There are so many interesting problems which advanced students, under direction, may tackle in the field of eugenics that I hardly know where to begin in making suggestions. There is always the opportunity for a student with interest in differences in people to seek out some trait in some accessible family, which trait is known by rumor ‘to run in the family.’ . . . Of course all these studies to be of value require extensive first-hand field work which involves careful description, diagnosis and measurement of human qualities.”70 Laughlin’s letter suggests that field workers are valuable in that they can, with care, detect dysgenic human qualities, such as feeblemindedness, even in their subtlest expressions; they also represent relatively cheap (and sometimes free) labor for the ever more precise business of measuring genetic quality. Stephen Jay Gould aptly described the increasingly stringent taxonomy of mental deficiency that U.S. and English eugenicists advanced from the 1910s to the 1930s:

Idiots and imbeciles could be categorized and separated to the satisfaction of most professionals, for their affliction was sufficiently severe to warrant a diagnosis of true pathology. They are not like us.

But consider the nebulous and more threatening realm of ‘high-grade defectives’—the people who could be trained to function in society, the ones who established a bridge between pathology and normality and thereby threatened the taxonomic edifice.71

Henry Herbert Goddard offered Deborah Kallikak, protagonist of The Kallikak Family, as an example of just such a taxonomic (and genetic) threat. He knows that Deborah looks normal.72 And he suggests that this is exactly the problem: “A large proportion of those who are considered feeble-minded in this study are persons who would not be recognized as such by the untrained observer. They are not the imbeciles or idiots who plainly show in their countenances the extent of their mental defect” (102–4). Just so, Deborah “has no noticeable defect” (7). For the modern white eugenicist, the menace of the “feebleminded” goes hand in hand with the menace of the mulatto. It is the unnoticeably mentally inferior, the feebleminded rather than the obviously retarded,

Frontispiece of The Kallikak Family (1912), a photograph of Deborah Kallikak, who was institutionalized at the Vineland Training School in New Jersey.

who constitute a national menace because they can pass for normal, just as the racially mixed threaten to pass for white.73 The family studies promise to eradicate the menace of the feebleminded, thereby restabilizing the “taxonomic edifice” of color and intelligence, along with the nation’s competitiveness. The field workers function as the trained observers who, even in the absence of the male eugenicist (trainer) himself, can always and everywhere detect, sometimes with just a glance, the intellectually liminal.74 And after detection comes treatment: institutionalization and sterilization. The June 1917 issue of Eugenical News sums up one such field worker’s extensive labor and its eugenical outcome: “Ethel H. Thayer, ’13, reports that at Letchworth Village from January 1, 1916, to April 1, 1917, she has spent 176 days in the field, has traveled about 10,000 miles, has interviewed 472 individuals and charted 1,984 and prepared 348 pages of descriptive material. . . . 7 were retained at the institution by the vote of the Board of Managers.”75 Here lies a (partial) solution for the eugenics field workers who must negotiate the conflicting demands of their own professional ambitions, the eugenic imperative that they breed, and the period’s gender restrictions. While they must be considered New Women, whose lives and labor challenge Victorian gender restrictions, the field workers are nevertheless able to “pass” as acceptable, conventionally feminine women because their work functions to restrict the unacceptable gendered and reproductive behaviors of others.76

The field workers, like all professional and activist women of the era, were at risk of being labeled by their critics as unfeminine or unnatural.77 The field workers’ particular professional activity—the identification and diagnosis of “feebleminded” women who otherwise would be “passing” for normal—permits them to “pass” for normal women themselves and concomitantly to help protect the nation, its gene pool, its womanhood, and its economy. In the context of the family studies, the primary perceived threat to healthy U.S. capitalism and its requisite gender roles is the mentally, rather than the racially, liminal; in other words, white feeblemindedness is the problem. And in fact, with the significant exception of Estabrook’s 1926 Mongrel Virginians, the family studies focus almost exclusively on the detection and elimination of those who are feebleminded rather than those who are of mixed race. There emerges in the family studies, then, an alternative version of the period’s “passing” narratives, with gender/class/intellect occupying the place customarily reserved for race. Authenticated as feminine by the “tenderness-sympathy” test and certified as intelligent by their college degrees, the field workers can thus legitimately test others for mental adequacy and for their adherence to middle-class gender roles.

WE MUST ACKNOWLEDGE that the field workers were expected to study and test dysgenic men as well as women; as a result, there are interclass, intergender politics embedded in the family studies as well—politics that have been largely overlooked.78 Perhaps because of scholars’ reliance on a maternalism-feminism model to theorize women’s activism in the reform era, we have been slow to theorize the ways that women exerted (sometimes damaging) power over men in the name of social reform in the 1910s and 1920s.79 The family studies show that the men in dysgenic families were also targets of eugenic gender policing and punishment often enacted, or at the very least enabled, by women field workers. Bernice Reed noted several “sissy” and “very feminine” men in the “defective” Trix family she knew from rural New Hampshire, men who were prone to “crime, drunkardness, and pauperism.”80 Typically in the family studies, a dysgenic woman was one who, as one woman field worker and study author put it, could not “order her life in accordance with the standards of morality in vogue in twentieth century society,”81 whereas the quintessential dysgenic man violated modern gender-economic-workplace standards, rather than gender-moral-domestic ones. In other words, while the tasks of the eugenicists were allotted according to a gendered division of labor (female field worker/data collector versus male author/diagnostician), dysgenic behaviors, too, were gendered. The earliest U.S. family study, Robert Dugdale’s The Jukes (1877) had from the start established this model of gendered dysgenics, which would characterize all the later family studies. Dugdale had argued that “prostitution in the woman is the analogue of crime and pauperism in the man.”82 Of course, these two aspects of eugenic prescriptiveness—the moral and the economic, the female and the male—were also inextricably linked from the start.

Photographs from The Kallikak Family of family members who were not institutionalized. The original 1912 captions read, on the left, “Great-grandson of ‘Daddy’ Kallikak. This boy is an imbecile of the Mongolian type”; and, on the right, “Malinda, Daughter of ‘Jemima.’” As Stephen Jay Gould first noted, the photographs have apparently been retouched, giving the subjects a menacing appearance.

The connection between a new form of economy and explicitly gendered forms of national subjectivity emerges quite clearly in the family studies. Both men and women in the increasingly post-rural/agricultural, industrial U.S. economy of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries must prove their fitness, their ability to add to national moral, economic, and genetic value in distinctly modern—and distinctly gendered—ways. In the family studies, the field workers are seeking reform within the social and historical context of this new economy and its new workplace. But, in contrast to the settlement house progressives who campaigned for antisweatshop legislation, the field workers sought to cull workers, like rural Minnesota’s “Timber Rats,” who appear incapable of surviving in such institutions of second-wave industrial capitalism as the sweatshop and the assembly line. James Knapp notes that as of “the end of the nineteenth century . . . it was widely believed that the advance of industry would not be able to continue at its past rate unless future improvements in the tools of work were accompanied by appropriate—and planned—changes in the workers themselves. Predictable uniformity was one of the changes most earnestly sought.”83 As of the 1910s, Fordism and Taylorism had conjoined to transform the nature of much American labor, as well as the ideal American laborer. Henry Ford’s Highland Park auto factory opened in 1910; it operated according to a production system (later termed Fordism) that “depended on standardization, mechanization, speed, efficiency, and careful control of production and workers.”84 Frederick Taylor published The Principles of Scientific Management in 1911. According to his principles, which came to be known as Taylorism, laborers were first to be selected to do work for which they were fit; they were then to be trained to perform ever more specialized tasks in an ever more tightly regulated and efficient system of manufacture.85 As a number of labor and cultural historians have noted, this system also effectively removes power and knowledge from the worker/craftsman and reassigns them to the managers, creating a self-perpetuating hierarchy of production and class.86

Granted, though Taylor’s system is certainly hierarchical, his emphasis on training appears decidedly anti-eugenic. However, his worker-selection process, as detailed below, sounds remarkably similar to the diagnostic process of the family studies. Here, Taylor describes his experiment in selecting one worker, from among a number of manual laborers, to haul pig iron: “A careful study was made of each of these men. We looked up their history as far back as was practicable and thorough inquiries were made as to the character, habits, and the ambition of each of them. Finally, we selected one from among the four as the most likely man to start with.”87 Taylor selects this person in part because he is “a man of the mentally sluggish type” (46), who “is suited to handle pig iron” and therefore “cannot possibly understand [the science behind producing and handling pig iron], nor even work in accordance with the laws of this science, without the help of those who are over him” (48). Like this particular expression of Taylorism, the family studies aim to select suitable modern male workers who can conform to the compartmentalized, fast-paced, and increasingly regulated workplace of the twentieth century. Unlike the family studies, however, Taylor’s hierarchical but at least partially progressive principles permit him to include immigrants and even the “mentally sluggish” in his ideal modern workplace. The family studies’ social conservatism, by contrast, leads them to construct both male producers and female reproducers according to an inherited nineteenth-century patriarchal, capitalist model: the family as the unit of consumption.88 In this view, the father, as worker, need only provide ever-increasing income, while the mother sustains home, morality, and ever-increasing spending.89 To the study authors and field workers, dysgenic families appeared mentally, behaviorally, and biologically unable to conform to such a “uniform, predictable” model of an ideal gendered economic unit—that is, the modern eugenic family first envisioned in Dugdale’s 1877 The Jukes.

The later family studies followed Dugdale’s original pattern of perceiving a gendered dysgenics in opposition to a mature, increasingly urban and industrial capitalist economy, but they also refined that pattern. As Rafter points out, in the “late family studies, disinterest in accumulation is a sure sign of feeblemindedness.”90 Their feebleminded subjects must not be maintained at the expense of a rapidly progressing nation; ever more people who cannot adhere to modern standards of either morality or production will necessarily be left behind. Calvin Coolidge, in his 1925 inaugural address, succinctly expressed these national imperatives: “The very stability of our society rests upon production and conservation. For individuals or for governments to waste and squander their resources is to deny these rights and disregard these obligations. The result of economic dissipation to a nation is always moral decay.”91 No other form of discourse more effectively accommodated a national platform of production, conservation, efficiency, and morality than did the family studies. As scientific management and assembly line production emerge as the predominant techniques of labor control, the family studies show a concomitant “tailoring” of the criteria for fitness.92 One such study, coauthored by a woman field worker and the male superintendent of the Minnesota School for the Feeble-Minded and Colony for Epileptics, Dwellers in the Valley of Siddem (1919), readily acknowledges this narrowing trend in the determination of mental fitness: “Our definition of feeblemindedness is a shifting one. A few years ago we did not recognize the high-grade moron as feebleminded. And, as Dr. Terman [reviser of the Stanford-Binet test] says, ‘. . . It becomes merely a question of the amount of intelligence necessary to enable one to get along tolerably with his fellows and to keep somewhere in sight of them in the thousand and one kinds of competition in which success depends upon mental ability. . . . It is possible that the development of civilization, with its inevitable increase in the complexity of social and industrial life, will raise the standard of mental normality higher still.’”93 Thus the family studies’ standards of normalcy, particularly for men, rose from the studies’ origin in 1877 to their peak in the late 1910s. Overall, the studies’ criteria become ever more stringent and more explicitly economic, as the ability to compete in the twentieth-century marketplace almost fully supplants appropriate moral behavior as their measure of male worth.

Family study author A. E. Winship, in his 1900 revision of Dugdale’s The Jukes, marks this transition by observing that “it is much easier to reform a criminal than a pauper.”94 In 1877, Dugdale had focused on the habitually criminal, whereas turn-of-the-century studies like Winship’s generally worried most about feeblemindedness and its possible results—immorality and sexual degeneracy among women, shiftlessness and unemployment among men. But even keeping a job becomes inadequate evidence to establish male genetic worth after the turn of the century and especially during World War I. A study coauthored by field worker Florence Danielson (published in 1912) focused on a “rural community of hereditary defectives” and noted about one dysgenic subject: “He was a good workman but lacked judgment and any idea of the value of money.”95 In 1918, field worker Mina Sessions published The Happy Hickories, a study of “the feeble minded in a rural county in Ohio.” She used a measure even more abstract and subjective than the IQ test to determine mental (and so genetic) adequacy. According to Sessions, those who were incapable “(a) of competing on equal terms with their normal fellows or (b) of managing themselves and their affairs with ordinary prudence” must be considered feebleminded.96 So by 1918, in order not to be labeled dysgenic, male study subjects had to be not only law-abiding and of at least average intelligence; they also had to know the value of a dollar and be competitive and prudent.97 World War I was clearly adding urgency to the project of establishing competitive national subjectivity; increasingly, international political and economic terms of engagement seemed to call for an ever purer and fitter nation.98 And some families were clearly not fit to produce or reproduce in a new global market, a new “Taylorized” workplace, or a new industrial economy. The danger lay in their continuing to reproduce anyway, in a kind of unnatural modern selection process. The field workers were thus essential for locating, diagnosing, and documenting those dangerously fecund dysgenic families who were, generation after generation, impairing the nation’s efficiency. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes remarked in 1927, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

THE EUGENICS field workers represent a group of reformers who cannot be fully understood via historians’ maternalism and professionalization-versus-reform paradigms for explicating women’s reform activism in the 1910s and 1920s. First, they were participating in what has been considered the “male dominion,” including discourse surrounding modern techniques of labor management and production, along with the concomitant discourse of economic and international competitiveness. Second, unlike the progressive women reformers, the field workers faced no contradiction between their professionalism and their politics; to restrict and confine their “clients”—through institutionalization and sterilization—precisely matched their reform agenda. Third, the field workers actually managed to finesse the period’s gender restrictions inasmuch as those restrictions might have conflicted with their own status as professionals; their eugenics work focused on improving American families even as it required the workers to possess and exercise their positive feminine attributes. As volunteers and professionals in a field that reinforced old-fashioned gender behaviors along with new-fashioned controls of population and labor, the field workers managed to remain “true” women even while they acted as New Women. The field workers must be viewed, then, as particularly successful examples of the New Woman who—though they always had to operate within the bounds of eugenic and capitalist ideologies and therefore remained constrained by a gendered family structure and a disciplinary economy—nevertheless exerted both discursive and literal power over women and men in a quite flexible and creative fashion. Indeed, in their unpublished writings, the field workers created a new genre. Combining personal narrative, travel narrative, interviews, genealogical data, and statistical analysis, the eugenics field workers wrote quintessentially modern national family stories.