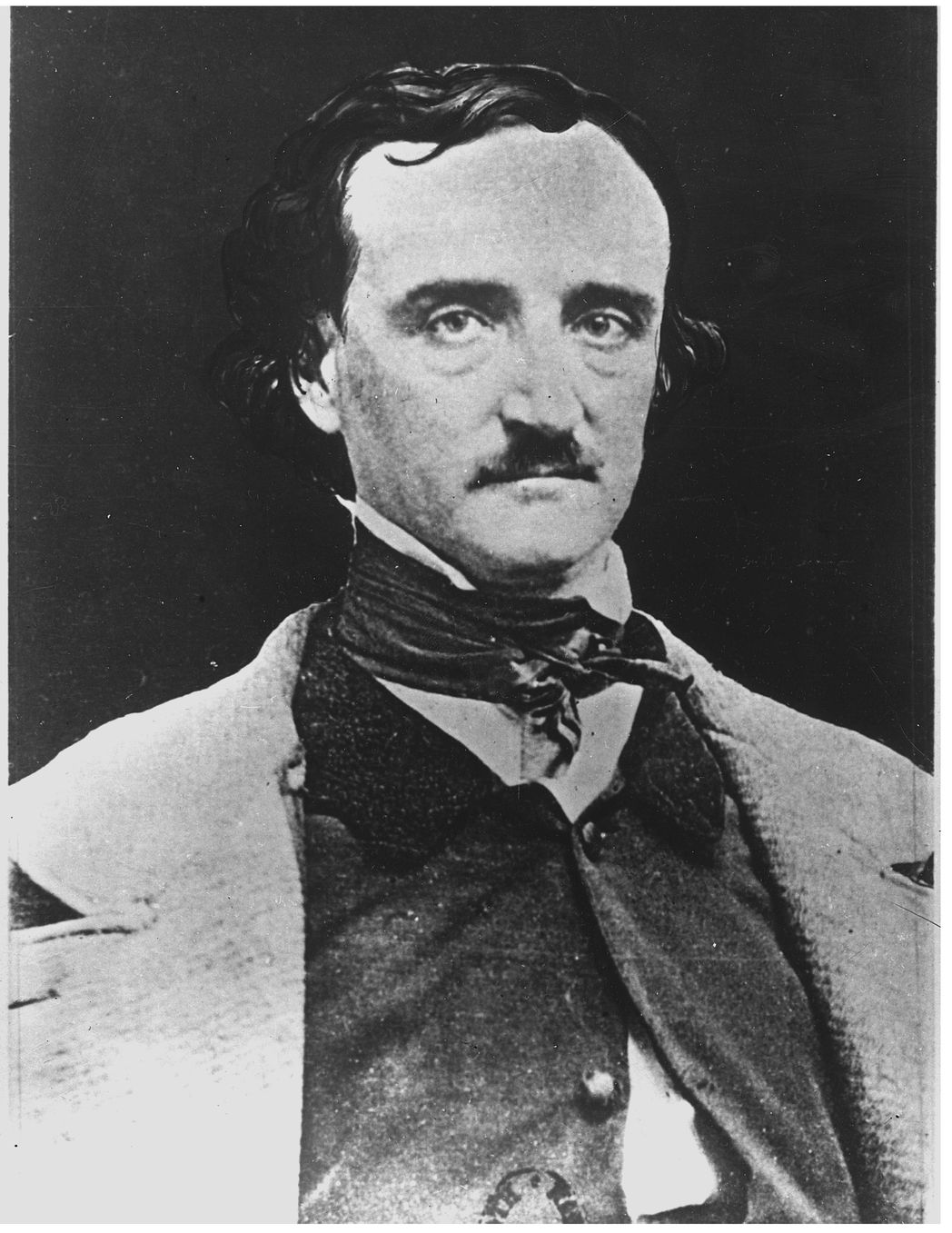

Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49) (daguerreotype) by Whitman, Sarah Ellen (19th century) © Biblioteque Nationale, Paris, France/The Bridgeman Art Library

3

POLAR GOTHIC: REYNOLDS AND POE

AFTER PARTING COMPANY WITH JOHN CLEVES SYMMES in Philadelphia, J. N. Reynolds continued lecturing on his own for the remainder of 1825 and into the next year. Unlike Symmes, he had considerable success, often charging fifty cents a head—roughly the equivalent of ten dollars today—and usually packing them in.

23 But his delivery wasn’t much snazzier than Symmes’. “According to our memory,” wrote historian Henry Howe, “he was a firmly built man, of medium stature, with a short nose, and a somewhat broad face. His delivery was monotonous, but what he said was solid, and his air in a high degree respectful and earnest and withal very sad, as though some great sorrow lay upon his heart, which won our sympathy, and this without knowing anything of his history.”

24 Reynolds’s first book-length publication,

Remarks on a Review of Symmes’ Theory, appeared in 1827, so his association with Symmes’ ideas continued for a time. But by degrees Symmes’ Holes began to close up or disappear in his talks, as increasingly he discarded Symmes’ theory and warmed to his true subject: the country’s vital need for a polar expedition. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that Reynolds was the one mainly responsible for churning up national enthusiasm for such an enterprise.

One eager enthusiast was Edgar Allan Poe.

There is continuing speculation regarding whether Poe and Reynolds knew each other personally. Their careers and interests intersected again and again. Poe took repeated literary inspiration both from Symmes’ theory and Reynolds’s speeches and writings, to the point of lifting certain passages from Reynolds wholesale. The question takes on extraliterary interest because of Poe’s enigmatic final words. On the night of October 7, 1849, Poe lay writhing in fear and pain on his deathbed, a ruin at forty. Over and over as he died, a single word came repeatedly to his lips: “Reynolds . . . Reynolds . . . Reynolds . . .”

25 No one knows why. Whether they actually knew each other has never been established, though my guess is that they must have.

When Reynolds began barnstorming the eastern states, Poe was a sixteen-year-old living in Richmond. In 1826, he spent eleven infamous months at the University of Virginia, chiefly devoting his time to gambling, unsuccessfully. While Poe was at the university, Reynolds wasn’t far away. “The center of Reynolds’s activities at first appears to have been Baltimore,” Robert Almy wrote in the February 1937 Colophon. “He delivered and repeated his course of lectures there in September and October 1826. At Baltimore Reynolds received not only a favorable press but offers of financial aid in fitting out an expedition to the South Pole.”

Stealing a leaf from his erstwhile mentor, in 1826 Reynolds began agitating for a national polar expedition. His focus was now on the Southern Ocean. The Antarctic was the larger unknown and the promise both of scientific discovery and commerce the greater for it. Although the main goal of such an expedition would be scientific, the scientists might turn up commercially useful information, such as the whereabouts of more seals and whales. New sources were needed to maintain the annual 4 million barrels of whale oil produced by New England. Almost 7 million whales had been killed by then, primarily to keep parlor lights burning on long winter nights.

Part of his campaign included speaking to state legislatures to persuade them to submit “memorials” to Congress—endorsements of the polar expedition idea urging government action. He also enlisted the interest of the open polar sea crowd. As already noted, the idea that open navigable sea lay beyond an icy rim was an ancient notion that continued to have great currency among prominent scientists and others you’d think would have known better. Like the Northwest Passage, it was an idea that people wanted to be true. Reynolds, like Symmes before him, mined the existing literature on polar exploration for anecdotal gems to place gleaming in his argument for the open polar sea and the bright possibilities it offered.

Finally, he called on national pride. The American republic itself was a green new enterprise, with many scoffers just waiting for it to fail; a national expedition would be a way to show the world what America was made of. There was no time to waste. Even this great southern unknown was beginning to give up its secrets to others.

The continent was first sighted in 1820, with three different contenders for the honor. Russians are certain it was their Admiral Bellingshausen, who was the first to circumnavigate Antarctica since Cook. The British are convinced it was Edward Bransfield and William Smith, who were on a mission to chart the South Shetland Islands. And Americans claim it was sealer Nathaniel B. Palmer, who in November 1820, as the twenty-one-year-old commander of the sloop Hero, sailed into Orleans Strait at about sixty-three degrees, forty-one minutes south and came within sight of the continent. The former teenage War of 1812 blockade runner is also credited with discovering the South Orkney Islands and later spent part of the 1820s transporting troops to help Simon Bolivar in South America. British sealing captain John Davis had made the first landing on Antarctica at Hughes Bay on February 7, 1821; but as there were no seals in sight, his party only stayed an hour and then split. That same year had marked the first Antarctic overwintering, when eleven men from the wrecked British ship Lord Melville toughed it out on King George Island. British explorer and sealer James Weddell, in three successive voyages—1819–1821, 1821–1822, and 1822–1824—was almost single-handedly turning the Southern Ocean into his private pond, having surveyed and named a number of the major Antarctic island groups, and, on the third voyage, encountering unusual ice-free conditions (more fodder for OPS believers), reaching seventy-four degrees, fifteen minutes south, beating Cook’s record by more than three degrees, in the sea presently named for him. Even as Reynolds was stumping for an expedition, the French were preparing to mount one of their own.

Should the United States be left behind?

On May 21, 1828, a resolution passed the House asking the president to devote a government ship to exploring the Pacific—if it could be accomplished with no extra appropriation of funds. President Adams told Reynolds he was pleased it had passed. Reynolds was named a special Navy Department agent to round up all the information he could. He interviewed every whaling and sealing captain he could find and sought out scientists for the voyage. He oversaw the rebuilding of the war sloop Peacock at the New York Navy Yard, which was launched to great hoopla in September 1828. But then things started to go wrong. A tangled series of reverses followed, due largely to the Adams’ administration’s lame-duck status. On taking office in March 1829, after handily beating Adams in the 1828 election, Democrat Andrew Jackson killed it for political reasons. Not only was it a leftover from the old administration, but Reynolds had been outspoken about his pro-Adams views. The expedition was canceled.

But Reynolds had a backup plan. One argument against the expedition during the legislative backpedaling that killed it had been a minimalist construction of the Constitution: it wasn’t the government’s business to be sponsoring and paying for such tomfoolery. As the prospects of a government expedition curdled, Reynolds formed the South Sea Fur Company and Exploring Expedition and went about rounding up backers and interested scientists. He was helped in this by Edmund Fanning, a longtime sealer and explorer (several discoveries in the central Pacific are credited to him) who had been proselytizing for a national Antarctic expedition since before the War of 1812. President Madison had commissioned him to lead a voyage and the ships were about to leave when war was declared against England, putting an end to that idea. Too old now to join himself, Fanning nevertheless helped Reynolds stir up interest in a private expedition.

A wealthy New Yorker named Dr. Watson came to the rescue, putting up most of the money for outfitting a ship and two small tenders. The kicker was that he got to go along. The Annawan and the Seraph, both brigs, and the Penguin, a schooner, sailed in October 1829 with Reynolds aboard—he’d gotten his polar expedition. Nathaniel Palmer captained one of the ships. Benjamin Pendleton, who as a sealer had often sailed into the unforgiving Southern Ocean, skippered another. James Eights of Albany, an accomplished artist and scientist, was resident naturalist. In a voyage that proved thin on accomplishments, Eights’s contributions stood out. In articles afterward he described a trilobite relative in the South Shetlands that wasn’t described again for seventy years. As they sailed west of the Antarctic Peninsula, he observed erratic boulders that differed geologically from the local rock, correctly surmising that they had hitched a ride here embedded in icebergs sheared from the Antarctic mainland. Eights also discovered the first fossils in the Antarctic, specimens of petrified wood, and a peculiar creature, a pyncnogonid, a ten-legged sea spider, the first so described.

The trip began inauspiciously, and got worse. Planning to sail south together, the ships quickly lost sight of each other and didn’t meet up again until they reached Staaten Island (Isla de los Estados), their rendezvous point just east of Tierra del Fuego. As they headed southeast for the South Shetlands, just north of the Antarctic Peninsula now partly named for Palmer, science and commerce found themselves at odds. The sailors had hired on for shares in the sealing take and became increasingly testy as the holds did not fill up. When they got to Antarctica, they found no sign of Symmes’ welcoming verges, open water, and balmy temperatures: “They at length arrived in sight of land,” Robert Way wrote shortly after the expedition, “which they afterward discovered to be a southern continent, which seemed completely blockaded with islands of ice.”

26 They attempted a landing in a long boat, but in the rough, stormy water it went careening for a considerable distance, out of sight of the ship, before they could reach the shore. They found themselves stuck there, without provisions. “Starvation seemed to stare them in the face.” Way continues:

But behold! Providence seemed to provide the means of support in the sea lion. He exhibited himself at the mouth of a cave, and ten men, in two squads, were sent out to bring him in. They soon returned with his carcass, which weighed 1,700 pounds. His flesh was excellent eating. By an accurate astronomical observation, they found their latitude to be eighty-two degrees south, exactly eight degrees from the South Pole. After some ten days of anxious delay on land, the sea becoming calm, they put out to sea in their long boat to endeavor to discover the ships. They sailed on and on for nearly forty hours. At length, being very weary, late in the night, they drew their boat upon a high inclined rock. All, in a few minutes, were sound asleep except Reynolds and Watson. They stood sentinels over the boat’s crew, and felt too anxious to sleep. About 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning, they saw a light far distant at sea. The crew was soon wakened, and all embarked in their boat and rowing with might and main for the ships. They soon arrived, and the meeting of the two parties was full of enthusiastic joy. They were convinced that they could not enter the South Pole, as it was blocked up with an icy continent; hence they were willing to turn their faces homeward. Here the seamen mutinied against the authority of the ship, set Reynolds and Watson on shore, and launched out to sea as a pirate ship.

Reynolds didn’t seem to mind. For many months he traveled all over Chile, and earned himself a footnote in American literary history—one of several—by hearing a supposedly true story about a renegade white whale in the Pacific off Chile, which he later wrote up for the May 1839 issue of

Knickerbocker magazine under the title “Mocha Dick, or the White Whale of the Pacific.” Guess who read it?

27Reynolds finally joined the warship USS Potomac in October 1832 at Valparaiso, Chile, as the commodore’s private secretary, remaining in that capacity during a two-year voyage and publishing a several-volume account of it in 1835 that made his reputation as an explorer and a writer.

In 1835 Poe was twenty-six years old and had already put together a pretty checkered track record. Born in Boston to a pair of itinerant actors, he lost his mother when he was two and then was bounced around from place to place. He attended the University of Virginia for eleven months in 1826, where he lost so much money gambling that his guardian yanked him out of school. Returning home, he learned that his sweetheart had dumped him and was engaged to another guy. In 1827 Poe landed in Boston, where he self-published a volume of poems, dripping youthful Byronic angst, called Tamerlane and Other Poems, to little notice. Dead broke, he enlisted in the army under an assumed name; his guardian apparently took pity on him, buying him out of the army and arranging an appointment to West Point. Poe got himself expelled by pulling a Bartleby and refusing to attend classes or drills. Before entering West Point, he’d published another volume of poems, Al Araf, Tamerlane, and Minor Poems, in 1829. After leaving West Point he went to New York City, where he published another volume, simply called Poems. These volumes contained some of his best work but nobody was buying, so he moved to Baltimore in 1831 and began to write stories.

By then he’d settled into the peculiar domestic arrangement that continued for many years—living with his devoted widowed aunt, Mrs. Maria Clemm, and his first cousin, her young daughter Virginia, whom he married in 1835 when she was thirteen years old. They had cramped barren rooms in a Baltimore boardinghouse and were desperately low on money. His aunt took in sewing to help pay the bills. Poe had long since begun his fatal dance with alcohol and opium. Certainly his brain was wandering through untraveled realms, but not of gold. His terrain was the “blackness of darkness.”

And he found inspiration in Symmes’ Hole.

Thanks largely to Symmes and Reynolds, the idea of the hollow earth had become linked with the fascinating mystery of the poles. Nobody had ever been there, at least to live and tell about it, so they offered complete artistic freedom, a tabula rasa on which anything could be written—made even more inviting by the imaginative addition of Symmes’ Holes.

Poe entered a literary contest sponsored by the Baltimore Sunday Visiter in 1833. First prize was $50—the equivalent of $750 today. Instead of submitting just one story, Poe sent several, which he had bound together in a makeshift book. The youngest of the judges, delegated as first reader of the “slush pile,” was so knocked out by one of the stories, “Ms. Found in a Bottle,” that he insisted on reading it aloud to the others, who agreed that it was a winner. The prize was announced and the story published in the October 19, 1833, issue. It was reprinted in the December 1835 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger.

Passing strange, this little tale. The world-traveling narrator begins with a disclaimer, saying that he has “often been reproached” for “a deficiency of imagination”—to make his bizarre account the more believable. He sails on a ship from Batavia, Java, bound for the Sunda Islands, “having no other inducement than a kind of nervous restlessness which haunted me as a fiend.” For days the ship is becalmed and then suddenly caught in the mother of all storms, a terrible “simoom”—“beyond the wildest imagination was the whirlpool of mountainous and foaming ocean within which we were engulfed.” Its first blast sweeps everyone on deck overboard and drowns those below, leaving only the narrator and an old Swede alive. The storm rages ceaselessly for five days, driving “the hulk at a rate defying computation” ever south, toward polar seas, “farther to the southward than any previous navigators.” The sun disappears and all is black; the seas remain dizzying, towering watery peaks and great chasms. While at the bottom of one, they spot a huge black ship far above, hurtling downward right at them. The crash propels the narrator into its rigging. He soon discovers the ship’s crew to be ancient ambulatory zombies who “seemed utterly unconscious of my presence” and “glide to and fro like the ghosts of buried centuries.” The floor of the captain’s cabin is “thickly strewn with strange, iron-clasped folios, and mouldering instruments of science, and obsolete long-forgotten charts.” This ship too races due south, borne by wind and a strong current, “with a velocity like the headlong dashing of a cataract.” And then, with just enough time for him to pop his manuscript into a bottle and cork it, the end: “Oh, horror upon horror! The ice opens suddenly to the right, and to the left, and we are whirling dizzily, in immense concentric circles, round and round the borders of a gigantic amphitheatre, the summit of whose walls is lost in the distance . . . we are plunging madly within the grasp of the whirlpool—and amid a roaring, and bellowing, and thundering of ocean and of tempest, the ship is quivering, oh God! And—going down.”

Poe’s debt to Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner is evident, but he owes his ending to Symmes’ Hole, sending his unfortunate narrator to his reward down its epic drain. Whirlpools seem to have been swirling through his mind at this time because another of the stories he submitted to the contest was “A Descent into the Maelstrom.” In this one, the narrator and a Norwegian fisherman sit high on a cliff’s edge overlooking the sea in northern Norway, and the tale consists of the fisherman relating how his ship was sucked down into the legendary maelstrom just offshore from where they’re sitting, and how he lived to tell the tale. Poe for purposes of verisimilitude inserts into the narrative a long description by Jonas Ramus, dating from 1715, which was reprinted in the 1823 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. The whirlpool here had long been noted by sailors, appearing on Dutch charts as early as 1590 and turning up on Mercator’s 1595 atlas. The Lofoten Islands lie entirely within the Arctic Circle on Norway’s northeastern shoulder, and a treacherous current, frequently whipped into a whirlpool, rushes between two of them, Moskenesøya (north) and Mosken (south). The hydrodynamics aren’t entirely understood—seemingly a combination of the current slamming into tidal shifts, with high winds sometimes thrown in. Poe amplifies the whirlpool to mythic proportions in his tale and suggests it may be the opening to a great abyss—citing no less an authority than Athanasius Kircher: “Kircher and others imagine that in the centre of the channel of the Maelstrom is an abyss penetrating the globe, and issuing in some very remote part—the Gulf of Bothnia being somewhat decidedly named in one instance. This opinion, idle in itself, was the one to which, as I gazed, my imagination most readily assented.” Kircher had argued that the maelstrom marked the entrance to a subterranean channel connecting the Norwegian Sea, the Gulf of Bothnia, and the Berents Sea, believing that such whirlpools were an important part of ocean circulation. “A Descent into the Maelstrom,” for all its stürm und drang, is less exciting than its companion piece, possibly because the fisherman lives through it, something the reader knows at the beginning.

One of the contest judges had been Maryland congressman and author John Pendleton Kennedy, whose Swallow Barn had been published pseudonymously in 1832, and who would become “the Maecenas of Southern letters”—with Poe being the first notable recipient of his patronage. As a result of the contest, they struck up a friendship, and Poe wasn’t shy about bemoaning his financial straits. Kennedy put him in touch with Thomas White, owner of the new, struggling Southern Literary Messenger. Poe began contributing to it. His first story appeared in March 1835 and more tales and poems followed. In August 1835, Poe moved to Richmond to become the magazine’s editor. He also wrote reviews, essays, and stories, as many as ten an issue. Under his editorship the circulation quadrupled in a year to around five thousand.

Poe didn’t last long as editor. Owner Thomas White fired him in January 1837 for erratic behavior caused by depression and drinking, though the parting probably had some mutuality to it. Poe had ideas about establishing a truly national magazine, and the natural place to try that was Philadelphia or New York. In late February, Poe, Virginia, and Mrs. Clemm had taken lodgings in an old brick building at Sixth Avenue and Waverly Place. Reynolds was also living in New York at this time. Poe contributed to the Southern Literary Messenger until he died; his final contribution, the poem “Annabel Lee,” ran in the November 1849 issue, a month after his death.

During his tenure at the magazine, Poe’s interest in Reynolds and things polar repeatedly showed itself. Before he took over as editor, in fact, a favorable review of Reynolds’s Voyage of the Potomac appeared in the June 1835 issue. The anonymous reviewer remarks that Reynolds “will be remembered as the associate of Symmes in his remarkable theory of the earth, and a public defender of that very indefensible subject, upon which he delivered a series of lectures in many of our principal cities.” Though apparently not a believer, the reviewer goes on to note that there’s “very valuable information scattered through the book,” and that “he writes well, though somewhat too enthusiastically, and his book will gain him reputation as a man of science and accurate observation. It will form a valuable addition to our geographical libraries.” The August 1835 issue notes that Reynolds’s Potomac has been “highly praised in the London Literary Gazette.”

The “Critical Notices” in the December 1835 issue—almost certainly written by Poe—contain an extensive detailed summary of what’s in the July 1835 issue of the

Edinburgh Review, a standard practice of the time revealing both slim literary pickings to write about and the ongoing American inferiority complex regarding things British. One article summarized is a review of Sir John Ross’s

Narrative of a Second Voyage in search of a North-West Passage, and of a Residence in the Arctic Regions during the years 1829 . . . 1833 . . . Including the Reports of Commander, now Captain, James Clark Ross . . . and the Discovery of the Northern Magnetic Pole. The

Edinburgh reviewer takes issue with calling it a “discovery,” quibbling in regard to whether his observations are entirely accurate. Poe agrees: “The fact is that the Magnetic Pole is

moveable, and, place it where we will, we shall not find it in the same place tomorrow.” He adds:

Notice is taken also by the critic that neither Captain nor Commander Ross has made the slightest reference to the fact that the Magnetic Pole is not coincident with the Pole of maximum cold. From observations made by Scoresby in East Greenland, and by Sir Charles Giesecké and the Danish Governors in West Greenland, and confirmed by all the meteorological observations made by Captains Parry and Franklin, Sir David Brewster has deduced the fact that the Pole of the Equator is not the Pole of maximum cold: and as the matter is well established, it is singular, to say no more, that it has been alluded to by neither the Commander nor the Captain.

This little tirade flaunts a flurry of knowledge about the subject—revealing an ongoing interest on Poe’s part—and echoes Symmes, Reynolds, and others who believed in the warmer open polar sea at the top and bottom of the world, an idea that would figure greatly in The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, his only published attempt at book-length fiction.

Another lengthy notice in the same issue, occupying three columns of eyestrain-size type, is a review of A Life of George Washington, in Latin Prose, by one Francis Glass, published by the reputable firm of Harper and Brothers, and edited, with a glowing introduction, by none other than J. N. Reynolds. One presumes that Poe had his tongue firmly planted in cheek when he wrote, “We may truly say that not for years have we taken up a volume with which we have been so highly gratified, as with the one now before us.” Glass too was from southwestern Ohio—he’d been Reynolds’s mentor. Poe has great (and uncharacteristically gentle) fun here, saying, “Mr. Reynolds is entitled to the thanks of his countrymen for his instrumentality in bringing this book before the public.”

In the February 1836 issue, Poe had asked a number of literary lights to contribute samples of their autographs for sportive analysis; included among James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, and John Quincy Adams was J. N. Reynolds.

A lengthy notice titled “South-Sea Expedition” appeared in the August 1836 issue, commenting on the publication in March of a “Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs, to whom was referred memorials from sundry citizens of Connecticut interested in the whale fishing, praying that an exploring expedition be fitted out to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas, March 21, 1836.” The review enthusiastically endorses the idea, calling it “of paramount importance both in a political and commercial point of view,” quoting Reynolds at length in several places. A news item appended to the end reports that the expedition has been given the go-ahead by the president, and that Reynolds has been named the expedition’s corresponding secretary, which the anonymous reviewer (in all likelihood, Poe) says is “the highest civil situation in the expedition; a station which we know him to be exceedingly qualified to fill.”

In April 1836 Reynolds had made a three-hour address to Congress offering reasons the country should underwrite such an expedition. He had shifted his public arguments to the economic benefits that would accrue. As far as the earth being hollow, “it might be so.” He was no longer very interested in the question. His own “bold proposition” now was that there could be an icy barrier around both poles, but “being once passed, the ocean becomes less encumbered with ice, ‘and the nearer the pole the less ice.’” In May 1836 Congress appropriated $300,000 for the enterprise. Reynolds’s address was subsequently published as a book by Harper’s, which Poe reviewed in a lengthy essay for the January 1837 issue of the Southern Literary Messenger. Again he heaps lavish praise on Reynolds—“the originator, the persevering and indomitable advocate, the life, the soul of the design.” Poe says it is needed because the fishery is of such importance to the country, but “the scene of its operations, however, is less known and more full of peril than any other portion of the globe visited by our ships.” The “full of peril” part suggests what is to come in Pym: “The savages in these regions have frequently evinced a murderous hostility—they should be conciliated or intimidated” (though in Pym those savages will have other ideas). There follows a detailed history of Reynolds’s efforts leading up to this, which notes that “the motives and character of Mr. Reynolds have been assailed.” But “we will not insult Mr. Reynolds with a defense. Gentlemen have impugned his motives—have these gentlemen ever seen him or conversed with him half an hour?” This last is the strongest indication we have that Poe and Reynolds actually knew each other.

Unfortunately for Reynolds, these “gentlemen” had the final say. Before the sailing date, he was dismissed from the post, and did not accompany the expedition that was largely his creation. It had partly to do with an ongoing antipathy on the part of the Navy to having civilians of any stripe aboard their ships; also, as delay began to follow delay, with the appropriation rapidly dwindling, Reynolds had been making his opinions known a little too loudly, and got on the wrong side of Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson. But the dismissal also showed the hand of Charles Wilkes, the expedition’s eventual leader, who had been clashing with Reynolds ever since the aborted 1828 effort.

28 From here on, perhaps understandably after such disappointment as a reward for such prolonged effort, Reynolds’ interests shifted away from the sea. He continued to write about earlier adventures—two such pieces appeared in the

Southern Literary Messenger, in 1839 and 1843, and “Mocha Dick” in

Knickerbocker in 1839—but he devoted the rest of his life to law and politics.

In 1840 he hit the boards in Connecticut as a campaign speaker for the Whigs, and in 1841 began a law firm on Wall Street, where he worked primarily on maritime law. In 1848, ever entrepreneurial, he organized a stock company for a mining operation in Leon, Mexico. The sketch of Reynolds in The History of Clinton County Ohio concludes: “He was elected president of the company, and, after a few years of persistent effort, he made quite a success in the field; but his health soon failed, and he died near New York City in 1858, aged fifty-nine years. He was buried in that city.”

Poe liked Reynolds and the address so much that he stole parts of it for

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, whose opening chapters were published serially in the January and February 1837 issues of the

Southern Literary Messenger. Poe also lifted details from Reynolds’s earlier

Voyage of the Potomac. Reynolds wasn’t alone in the honor. Poe ransacked existing seagoing literature for his tale about Pym, appropriating left and right, and returned to Symmes’ Hole for his big finale.

29Poe’s timing in writing Pym showed his good commercial instincts—he was a magazine editor, after all. The voyage had captured the national imagination and was just under way when Poe’s novel came out, which left him free to cook up the grisly possibilities he envisioned for his own Antarctic excursion. Even so, the book didn’t sell very well, and Poe returned to the shorter work at which he was far more accomplished.

Literary historian Alexander Cowie summed up Pym as “a plotless, nightmare-ridden book.” Right on both counts, but it nonetheless holds a certain fascination, however morbid. For all its faults, which are many, it is a lot of gruesome fun. A seeker of extreme sensation in life, it makes sense that Poe would push every boundary he could think of in his writing. One literary form of pushing limits is parody, and Pym is arguably that as well, a ghastly gothic send-up of that literary staple, the journal of a polar voyage. It bears an uncanny resemblance to one polar voyage in particular—Symzonia. A number of scholars have pointed to Symzonia as a likely model. In Pilgrims Through Space and Time, J. O. Bailey, citing a long list of parallels, suggests that it might have been called Pymzonia. But with all its debts to Symzonia—and Poe truly seems to have used it as a template for his own tale—Pym takes these elements to the outer limits. And it’s all done deadpan, with a straight face. Poe admired Robinson Crusoe for its seeming verisimilitude, and all that ransacking of marine literature, with the occasional outright theft for good measure, at first gives the book the superficial aspect of being just another voyager’s account of his travels; the realistic, matter-of-fact journalistic tone continues as events get more and more outrageous. Poe loved hoaxes, and he does his damnedest in Pym to carry it off.

But there are hints early on. Before the voyage is under way, the young narrator rhapsodizes about his hopes for the trip: “For the bright side of the painting I had a limited sympathy. My visions were of shipwreck and famine; of death and captivity among barbarian hordes; of a lifetime dragged out in sorrow and tears, upon some grey and desolate rock, in an ocean unapproachable and unknown.” Mind you, this is what he hopes will happen. And does he ever get his wish!

Pym is sneaked onboard by his friend Augustus, deposited as a stowaway in a dark claustrophobic hold, from which he soon finds he cannot get out, beginning the voyage in a sort of burial alive, one of Poe’s favorite terrors. While he’s stuck in this fetid compartment, up on deck the crew is mutinying. For days he nearly starves and goes mad, and is threatened by man’s best friend, a dog trapped in there with him. Finally Augustus springs him. Joined by thuggish-looking half-breed Dirk Peters, the three kill all the mutineers but one and retake the vessel. But, wouldn’t you know it, a protracted gale reduces the ship to a floating wreck, kept from sinking by its buoyant cargo of oil. They can’t get at the food in the hold, so it’s either death by starvation or being washed overboard.

Then a ship approaches with what proves to be an ex-crew. “Twenty-five or thirty human bodies, among whom were several females, lay scattered about . . . in the last and most loathsome state of putrefaction.” On one sits a seagull, “busily gorging itself with the horrible flesh, its bill and talons deeply buried, and its white plumage spattered all over with blood.” A tip of the hat to Coleridge for that scene. Another vessel comes by but doesn’t see them.

Dirk Peters, as imagined by artist René Clarke, looking cheerfully sinister and ready to rock with his bottle of rum and shiv on his belt, in a 1930 edition produced by Heritage Press for the Limited Editions Club. (© 1930 by The Limited Editions Club [George Macy Companies, Inc.])

Now they’re really starving. They begin sizing each other up as possible entrees. They draw lots, and Parker, whose idea it was, gets the short straw. Dirk Peters, living up to his first name, stabs him. For the next four days the others nosh on Parker’s diminishing remains. Finally Pym figures out a way to cut a hole into the storeroom, which is filled with water, so they have to dive repeatedly to bring up whatever they can—a bottle of olives, a bottle of Madeira, and a live tortoise. Augustus has injured his arm, which begins turning black, and he wastes away, a mere forty-five pounds when he dies. When Peters tries to pick him up, one of Augustus’s legs comes off in his hands. Can things get worse? Of course. The hulk rolls over. But the three survivors manage to clamber up on it, and, in one of those ironies that made Poe smile, what do these starving men find on the hull? Plenty of nutritious barnacles. They catch rainwater in their shirts.

It’s brutally hot, but they can’t cool off in the ocean because of the sharks endlessly cruising around them. They’re dying. But then another ship approaches, the Jane Guy, and this time they are saved—briefly. This whaler heads farther south, piercing the southern ice barrier into temperate seas. As the climate becomes increasingly warmer—just as it does in Symzonia—they come upon an island near the South Pole populated by seemingly friendly savages. But it turns out to be one of the strangest and most sinister islands in literature. Everything, every plant and creature, even the water, is black. The woolly-haired natives even have black teeth—and not from not brushing. White in any form is unknown to them, except for the strange white animal (with red teeth) they worship as a terrible totem. The natives come out to meet the Jane Guy in large sea canoes, greeting them with cries of Anamoo-moo and Lama-Lama. For a few days everything is swell. But then they set an ambush for the crew, killing them in a landslide; they head out in canoes to burn the Jane Guy, which proves a miscalculation when the gunpowder in the hold explodes, sending body parts flying. All the crew are dead but Pym and Peters, fortuitously semi-buried alive (again) in a rock chamber during the landslide. They manage to escape in a native canoe, abducting one Nu-Nu to accompany them as a guide, but he proves useless, lying in the canoe bottom writhing in fear and dying a few days later. A persistent current draws their little craft ever southward. A gray vapor is seen rising above the horizon.

Boat adrift. “The wind had entirely ceased, but it was evident that we were still hurrying on to the southward, under the influence of a powerful current.” (© 1930 by The Limited Editions Club [George Macy Companies, Inc.])

The seawater becomes hot to the touch and takes on a milky hue. “A fine white powder, resembling ashes—but certainly not such—fell over the canoe and over a large surface of the water.” A day later, “the range of vapor to the southward had arisen prodigiously in the horizon, and began to assume more distinctness of form. I can liken it to nothing but a limitless cataract . . . we were evidently approaching it with a hideous velocity.” Not counting a short afterword, which Poe provides to continue the pose that this has been an actual nonfiction account, these are the final lines:

Many gigantic and pallidly white birds flew continuously now from beyond the veil, and their scream was the eternal Tekeli-li! as they retreated from our vision . . . and now we rushed into the embraces of the cataract, where a chasm threw itself open to receive us. But there arose in our pathway a shrouded human figure, very far larger in its proportions than any dweller among men. And the hue of the skin of the figure was of the perfect whiteness of the snow.

Go figure. He says in the afterword that the final two or three chapters have been lost, regrettable because they no doubt “contained matter relative to the Pole itself, or at least to regions in its very near proximity; and as, too, the statements of the author in relation to these regions may shortly be verified or contradicted by means of the governmental expedition now preparing for the Southern Ocean.”

Pym’s abrupt ending has puzzled and annoyed readers and critics alike. Did Poe simply weary of a bad business, as many have suggested? Could be. But its very abruptness adds a final element of ambiguity missing from the rest of the book. Toward the end Poe begins toying with the symbolic possibilities of whiteness and, less happily, blackness. Critic Leslie Fiedler has argued persuasively that taking his white characters way down south to the all-black island represents southern racist dreaming, nightmare division, a macabre South Seas rendering of that deepest slaveholder dread—a slave insurrection. “The book projects his personal resentment and fear,” says Fiedler, “as well as the guilty terror of a whole society in the face of those whom they can never quite believe they have the right to enslave.”

Whiteness doesn’t fare too well either. In The Power of Blackness, Harry Levin sees in that final whiteness “a mother-image.” Levin says “the milky water is more redolent of birth than of death; and the opening in the earth may seem to be a regression wombward.” But Fiedler finds in the engulfing womblike whiteness of the cataract a perverse twist on the great mother symbol. Clearly, despite the postscript, Pym and Peters are sucked down to their deaths, and Fiedler sees this final and fatal embracing whiteness as “the Great Mother as vagina dentata.” Ouch! And Poe uses Symmes’ Hole to chew up his hapless hero! “From the beginning,” Fiedler says, “a perceptive reader of Gordon Pym is aware that every current sentimental platitude, every cliché of the fable of the holy marriage of males is being ironically exposed.”

I would suggest an even wider reading—that Pym is also a send-up of the mania for polar exploration and the bright sunny possibilities being trumpeted by Reynolds & Co. Was Poe among the enthusiasts? Yes. Could he help seeing the dark humor in all this optimism? Or resist sticking it to the whole bunch, even though he admired Reynolds and thought the expedition was cool? It would seem not. The book’s commercial failure may have had less to do with its gory excesses and/or artistic deficiencies (it really is better and more fun to read than it’s supposed to be) than its naked subversiveness regarding this particular scene in the American Dream.

Interestingly, Poe found an ally in Henry David Thoreau, who also had something to say about the national enthusiasm Reynolds generated for exploration of the South Pole and about Symmes’ Hole too, though his comments in the concluding chapter of

Walden (1854) were typically contrarian and transcendental, making metaphysics of it all:

What was the meaning of that South-Sea Exploring Expedition, with all its parade and expense, but an indirect recognition of the fact that there are continents and seas in the moral world to which every man is an isthmus or an inlet, yet unexplored by him, but that it is easier to sail many thousand miles through cold and storm and cannibals, in a government ship, with five hundred men and boys to assist one, than it is to explore the private sea, the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean of one’s being alone . . . It is not worth the while to go round the world to count the cats in Zanzibar. Yet do this even till you can do better, and you may perhaps find some “Symmes’ Hole” by which to get at the inside at last.

Good old Henry, ever marching along to that different drummer. Explore the Symmes’ Hole within you—it is more mysterious and profound.