Photo of Cyrus Reed Teed (“Koresh”) on the grounds of his utopian community in Estero, Florida, along with a Koreshan promotional card. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

5

CYRUS TEED AND KORESHANITY

AROUND MIDNIGHT, EARLY AUTUMN 1869. Yellow wavering kerosene light dances off jars of colorful compounds, retorts, odd electrical devices, and other singular equipment in a little “electro-alchemical” laboratory near Utica, New York. Thirty-year-old Cyrus Teed has been working here all day and into the night, with great result.

As he later wrote in The Illumination of Koresh, he had discovered “the secret law and beheld the precipitation of golden radiations, and eagerly watched the transformation of forces to the minute molecules of golden dust as they fell in showers through the lucid electro-alchemical fluid . . . I had succeeded in transforming matter of one kind to its equivalent energy, and in reducing this energy, through polaric influence, to matter of another kind . . . The ‘philosopher’s stone’ had been discovered, and I was the humble instrument for the exploiter of so mag-nitudinous a result.”

Discovering the philosopher’s stone—figuring out the age-old mystery of turning base metal into gold—would seem to be enough for one day’s work. But Teed wasn’t done for the night. “I had compelled Nature to yield her secret so far as it pertained to the domain of pure physics. Now I deliberately set myself to the undertaking, of victory over death . . . the key of which I knew to be in the mystic hand of the alchemico-vietist.” Hard to say exactly what he meant by alchemico-vietist, but a likely deconstruction is an alchemist working on the mysteries of life forces. In any case Teed considered himself one. He next explains his view of the universe, which leads to his greater immediate goal:

I believed in the universal unity of law. I regarded the universe as an infinitely (the word is here employed in its commonly accepted use) grand and composite structure, with every part so adjusted to every other part as to constitute an integrality, constantly regenerating itself from and in itself; its structural arrangement in one common center, and its forces and laws being projected from this center, and returning to the common origin and end of all. I had taken the outermost degree of physical and material substance, that in which was the lowest degree of organic force and form, for my experimental research. Having in this material sphere made the discovery of the law of transmutation, law being universally uniform, I knew, by the accurate application of correspondential analogy to anthropostic biology, that I could cause to appear before me in a material, tangible, and objective form, my highest ideal of creative beauty, my true conception of her who must constitute the environing form of the masculinity and Fatherhood of Being, who quickeneth.

Teed loves nine-dollar words and isn’t shy about making up new ones. Whatever he might mean about applying correspondential analogy to anthropostic biology (anthroposophy was a current term for knowledge of the nature of man), it seems he’s trying to say that what he had achieved in transforming material substances he now intended to apply to the spirit, to make manifest his “highest ideal of creative beauty,” though saying that she would be the embodiment of the “Fatherhood of Being” seems a little foggy. He sits in a thoughtful attitude and concentrates with all his might.

I bent myself to the task of projecting into tangibility the creative principle. Suddenly, I experienced a relaxation at the occiput or back part of the brain, and a peculiar buzzing tension at the forehead or sinciput; succeeding this was a sensation as of a Faradic battery of the softest tension, about the organs of the brain called the lyra, crura pinealis, and conarium. There gradually spread from the center of my brain to the extremities of my body, and, apparently to me, into the auric sphere of my being, miles outside of my body, a vibration so gentle, soft, and dulciferous that I was impressed to lay myself upon the bosom of this gently oscillating ocean of magnetic and spiritual ecstasy. I realized myself gently yielding to the impulse of reclining upon this vibratory sea of this, my newly-found delight. My every thought but one had departed from the contemplation of earthly and material things. I had but a lingering, vague remembrance of natural consciousness and desire.

36It has been suggested that this illumination was nothing more than an accidental near-electrocution from the electricity he was so fond of fiddling with, a zzzolt! to the brain that, instead of killing him, produced this vision. Ye of little faith!

Suffused by this ocean of electro-magneto-spiritual energy, he lies back on it, as if on a mystical water bed, drifting away into an unknown ecstasy. He has lost his body. “I started in alarm, for I felt that I had departed from all material things, perhaps forever. ‘Has my thirst for knowledge consumed my body?’ was my question.” A touch of Faust here. He can’t feel his body. He opens his eyes but can’t see anything at first. Then he hears “a sweet, soft murmur which sounded as if thousands of miles away.” He tries to speak, but it is in a voice he has never heard before. “Yet it was my own effort, and I knew it came from me. I looked again; I was not there.”

“Fear not, my son,” he finds himself saying in this strange voice, “thou satisfactory offspring of my profoundest yearnings! I have nurtured thee through countless embodiments . . .” The voice continues its revelations, taking him on a journey through his many past lives, good, bad, and horrible. The voice then tells him to look and “see me as I am, for thou has desired it. Offspring of Osiris and Isis, behold the revailing [sic] of thy Mother.”

He sees a “light of dazzling brilliancy” appear. A sphere of luminescent swirling purple and gold, and “near the upper portion of its perpendicular axis, an effulgent prismatic bow like the rainbow, with surpassing brilliancy. Set in this corona or crown were twelve magnificent diamonds.” This acid trip light show gradually resolves into human form—a beautiful woman. A very beautiful woman. Standing on a silvery crescent, holding a winged staff with entwined serpents—a caduceus, symbol of the medical profession—she wears a royal purple and gold gown, has “golden tresses of profusely luxuriant growth over her shoulders,” and “exquisite” features. It is God herself! She reveals that she is the Father, the Son, and the Mother, all in one. “I have brought thee to this birth,” she says, “to sacrifice thee upon the altar of all human hopes, that through thy quickening of me, thy Mother and Bride, the Sons of God shall spring into visible creation.” And she has a lot more to tell him.

At last the vision ends and Teed finds himself lying on the couch in his laboratory. He closes the

Illumination by recounting his achievement in demonstrating the “law of transmutation”:

I had . . . demonstrated the correlation of force and matter. I had formulated the axiom that matter and energy are two qualities or states of the same substance, and that they are each transposable to the other . . . In this I knew was held the key that would unlock all mysteries, even the mystery of Life itself.

What’s eerie about this is that through the most occult, electro-alchemical path, Teed has arrived at an idea—matter is energy, energy matter, simply different forms of the same thing—that would shortly become an essential scientific truth.

But then he says he made this transmutation spiritually as well:

I had transformed myself to spirituous essence, and through it had made myself the quickener and vivifier of the supreme feminine potency . . . While thus inherent and clothed upon with the femininity of my being, how vividly was awakened in my mind the memory of the passage of Scripture found in Jeremiah xxxi: 22: “How long wilt thou go about, O thou backsliding daughter? For the Lord hath created a new thing in the Earth, a woman shall compass a man.”

Through force of will Teed not only summoned God to appear to him, but he

really got in touch with his feminine side! The main points of Teed’s

Illumination are summarized in Sara Weber Rea’s

The Koreshan Story (1994):

• The universe is a cell, a hollow globe, eternally and perpetually renewing itself by virtue of involution and evolution, and all life exists on its inner concave surface.

• God being perfect is both male and female—a biune being, and personal to every individual.

• Matter and energy are inter-convertible. Matter is destructible resulting in transmutation of its form to energy and conversely, from energy to form.

• Reincarnation is the central law of life—one generation passing into another with all humanity flowing down the stream of life together.

• Heaven and hell constitute the spiritual world. That is, they are mental conditions and within mankind.

• The Bible is the best written expression of the Divine Mind but is written symbolically. The symbolism must be interpreted by a prophet who would appear in every age and in the context of that age.

• Man lives best by communal principles to correspond with the primitive Christian church. The Koreshan form of socialism would be the expression of the natural laws of order, to include the elimination of money power and wage slavery.

• Equity, not equality, is a natural law for women as for men. There is no equality, and to say any two people are equal is merely trying to enforce uniformity.

Amazing that Teed got all this down without taking notes. And that wasn’t all. Rea adds, “Dr. Teed indicated there was a great deal more knowledge that had been imparted to his mental consciousness, but he felt the ordinary minds of mortals could not immediately comprehend or evaluate it. It would be presented to the world in time.”

So: the earth is hollow and we all live inside. Teed is the second coming of Christ. God is male and female. Matter and energy are interchangeable. Reincarnation is a fact of existence. Heaven and hell are within us. The Bible should be read symbolically, not literally. People should live according to communal socialist principles—no money. Equity for men and women.

These ideas are part of a mainstream of American millenarian thinking that goes back to the Pilgrims and the Boston Puritans. Eschatological details varied, but the thread of the last days being upon us shines through the fabric of American history, with new messiahs practically a dime a dozen. What sets Teed apart is his insistence that the earth is hollow and that we all live inside a “cosmic egg.” Robert S. Fogarty briefly summarizes Teed’s cosmology:

He discovered that the universe is all one substance, limited, integral, balanced and emanating from one source, God. The Copernican theory of an illimitable universe was false because the earth had a limited form: it was concave . . . The sun is an invisible electro-magnetic battery revolving in the universe’s center on a 24 year cycle. Our visible sun is only a reflection, as is the moon, with the stars reflecting off seven mercurial disks that float in the sphere’s center. Inside the earth there are three separate atmospheres: the first composed of oxygen and nitrogen and closest to the earth; the second, a hydrogen atmosphere above it; third, an aboron

37 atmosphere at the center. The earth’s shell is one hundred miles thick and has seventeen layers. The outer seven are metallic with a gold rind on the outermost layer, the middle five are mineral and the five inward layers are geologic strata. Inside the shell there is life, outside a void. One can then understand why the Koreshan group was reported to have sported badges which proclaimed “We live on the inside.”

38

Chart depicting Koreshan cosmogony from an 1880s edition of the Flaming Sword. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

These details were elaborated over time and remained central to Teed’s theology, even though his insistence on the earth’s hollowness and our interior living arrangements got him branded a crackpot and worse. Ready to take his lumps, he declared, “To know of the earth’s concavity is to know God, while to believe in the earth’s convexity is to deny Him and all His works.” No ambiguity there.

Although Teed’s conviction that the earth is hollow had antecedents in the work of Edmond Halley, Cotton Mather, John Cleves Symmes, and Jules Verne, he was the first to claim we’re living in it.

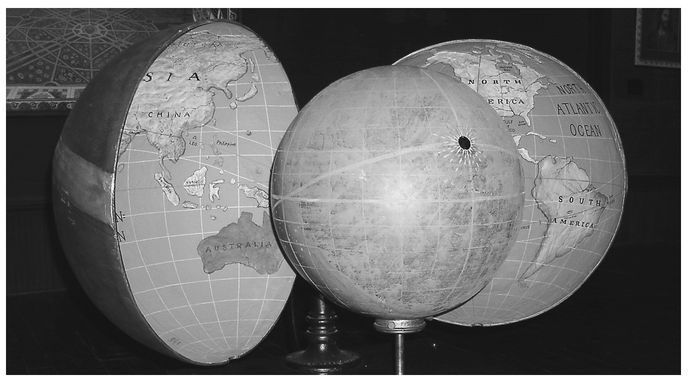

Teed’s hollow globe, on display in Art Hall at the Koreshan Historic Site in Estero, Florida. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

A “scientific” book supporting the earth’s hollowness appeared in 1871 and went through several editions in the next few years. Whether Teed read it isn’t known. But it contains notable parallels to his ideas, particularly in regard to their inspiration and electromagnetism. It had the slightly askew title

The Hollow Globe; or The World’s Agitator and Reconciler. The title page writing credits are revealing:

Presented through the Organism of

M. L. SHERMAN, M.D.,

And Written by

PROF. WM. F. LYON

As Professor Lyon humbly relates in the preface, he had little to do with the “original, natural and startling ideas, which seem to be entirely irrefutable,” since they were channeled from the spirit world through Dr. Sherman, and Professor Lyon simply wrote them down. He says that in September 1868, he was sitting in his Sacramento office “when a strange gentleman made his appearance” and told Lyon that he had repeatedly “been thrown into a semi-trance condition becoming partially unconscious of his earthly surroundings” (sound familiar?). During this trance spirits gave him scientific information about the nature of the world. Over the next months, Sherman conveyed these ideas “in broken fragments” to Lyon, who organized them. In some respects they are a further iteration of existing hollow earth ideas and in others represent a new departure.

Like many hollow earth theorists going back to Halley, the authors in chapter 1 insist on divine purpose but give it a peculiarly American manifest destiny twist. After charting the American movement westward and citing the human universality of this drive, they point out that America is filling up and people will soon have nowhere to go. (This is actually forward-looking, since historian Frederick Jackson Turner didn’t declare the frontier a goner until 1893.) But an all-wise spirit wouldn’t permit this thwarting of human need and so, voilà, the paradisiacal hollow earth awaits! Humanity not only needs it to be there, it would be a horrible waste of space if it weren’t.

39 But how to get inside? Here the authors fall back on Symmes (without naming him): a vast opening at the pole. What about all that ice? Chapter 2 takes up another standby, the open polar sea. It definitely exists, and a passage will be found through the ice, probably through the Bering Straits. What about the burning heat that’s supposed to be down there, per prevailing geological thinking? Chapter 3, “The Igneous Theory,” demolishes that folly. Okay, then what about volcanoes and earthquakes? These occupy chapters 4 and 5. And here’s where we see a new wrinkle in hollow earth thinking. Lyons goes to great pains, and into frightening detail, to show that what causes them—as well as what holds the fabric of the earth together—is a complex electromagnetic matrix that I won’t even attempt to describe. This insistence on electromagnetism as the essential force at work is something new, and it’s also essential in Teed’s formulation.

Electromagnetism was a hot topic in science at the time. The nineteenth century could be designated the Electrical Century, starting in 1800 with the first electric battery developed by Alessandro Volta, followed by the discovery of electro-magnetism by Hans Christian Oersted in 1820. Samuel F. B. Morse was granted a patent on the electromagnetic telegraph in 1837, and this heralded all the electric wonders to come before century’s end: incandescent light, the telephone, phonograph records, movies, radio. So it makes sense that electromagnetism would also be incorporated into the most trendy and up-to-date metaphysics, both by Sherman/Lyon and Cyrus Teed.

Promulgating these ideas would be a large order for a young man whose life so far had been undistinguished at best. Teed had been born in 1839 in the village of Trout Creek, New York, one of two sons among eight children. The family moved north to the Utica area when he was just a year old. By an odd coincidence, he was a distant cousin to Joseph Smith, whose own vision (a pillar of fire that turned into God and Jesus) as a teenager in 1820, just three hundred miles from Utica, led to the founding of the Mormon Church.

As a child, Teed showed no particular spark. He quit school at age eleven to work on the Erie Canal, as a driver on the towpath of the canal, which had been completed twenty-five years earlier. At some point he started to study medicine with a physician uncle. At twenty-two he enlisted in the Union army as part of the medical corps; he had already married Delia M. Row, a distant cousin, and fathered a son, Douglas. After Teed was released from the army, he returned to New York to continue studying medicine at the Eclectic Medical College—an esoteric institution that emphasized what would be called alternative remedies today. As Fogarty characterizes it, “Eclectic practitioners were more poorly educated than regular physicians, combined a variety of methods derived from regular and homeopathic medicine and, in the main, had their practices in smaller communities. Some eclectics were disreputable charlatans while others worked in the botanical drug tradition and served their communities as well as the other sects.”

After graduating in 1868, Teed moved to Deerfield, New York, to join his uncle in practice. According to Peter Hicks, they hung out a sign saying, “He who deals out poison, deals out death.” Hicks explains: “They were referring to drugs— a very busy pharmacy . . . an half block away shows no record of the Teeds ever writing a prescription. However, below the doctors’ office was a tavern, and people found this reference to poison very humorous.”

40 Teed called his approach to medicine “electro-alchemy,” blending “modernized” alchemy with strategically placed zaps of electric current and doses of polar magnetism, a mixture of science (of a sort) and mysticism that would continue in his religious efforts. During his illumination, the lovely manifestation of God had also told him, as Hicks puts it, “that he would interpret the symbols of the Bible for the scientific age.”

After this profound spiritual experience, Teed couldn’t resist adding his metaphysical insights to the other restoratives he offered his patients. But most didn’t want to hear about how we’re living inside the hollow earth and that Copernicus had it all wrong from someone they were trusting to take care of their ailments. His practice, barely a year old when his illumination occurred, began to suffer, and the Teed family made the first of many moves in hopes of doing better somewhere else. He next tried his peculiar amalgam of doctoring and cosmic revelation in Binghamton, New York.

In 1873 he and Dr. A.W.K. Andrews—a close friend and one of his first true believers—visited the Harmony Society in Economy, Pennsylvania, a few miles above Pittsburgh. It was his first close-up look at a utopian religious community, and the experience put a gleam in his eye. As it happened, Harmonist founder George Rapp had been a fellow alchemist.

In their time, the Harmonists were among the more successful of the communal religious societies that sprouted like wildflowers all over the Northeast and Midwest during the nineteenth century. There were so many in New York alone that a swath through the center of the state was known as the “burned-out area” for the fervent religiosity and communal experiments it had seen. Teed’s spiritual revelation, leading him to create his own religious sect and utopian community, was not some isolated sport. His ideas about living inside the hollow earth were novel, but he was hardly alone in cooking up a new religion and establishing a community based on his ideas. It was going around. As Emerson famously wrote in a letter to Carlyle in 1840:

We are all a little wild here with numberless projects of social reform. Not a reading man but has a draft of a new community in his waistcoat pocket . . . One man renounces the use of animal food; and another of coin; and another of domestic hired service; and another of the State.

The Harmonists had gathered to lead lives that would prepare them for the Second Coming of Christ, which they were certain was right around the corner. The society was communist, with no privately held property, and all worked for the common good. They felt they were following the model of the primitive Christian church—“united to the community of property adopted in the days of the apostles,” said their Articles of Association. They also practiced celibacy, believing it to be a higher state than marriage. Both these ideas would turn up in Teed’s program.

Teed continued, reluctantly, to stay on the move, trying various towns in New York and Pennsylvania. Around the time he visited the Harmonists, his wife’s health took a bad turn, and she went with their son, Douglas, to live with her sister in Binghamton, where she remained until her death in 1885. Teed seems to have largely put them behind him to become the new hollow earth messiah. After his wife’s death, Douglas was taken in by a Mrs. Streeter, who supported him emotionally and financially and also provided the means for him to study art in Italy. Teed had other things on his mind.

In 1878, he visited another successful utopian community, the Shaker enclave at Mount Lebanon, New York, near the Massachusetts border just west of Pittsfield. According to Peter Hicks he was admitted as a member in the North Family there. This was the first formal Shaker community, consisting then of almost four hundred people, and one of fifty-eight such Shaker groups scattered as far west as Kentucky.

The Shakers had come together around Ann Lee, an Englishwoman born in 1736. At twenty-three she joined a Quaker society of a spirited sort that earned them the nickname “Shaking Quakers” because of the way they shook, whirled, and trembled to be rid of evil. They suffered persecution, and in 1770 Ann Lee had her illumination in jail. “By a special manifestation of divine light the present testimony of salvation and eternal life was fully revealed to her,” as a Shaker history from 1859 puts it. Ann Lee learned that she was the Second Coming of Christ, and in 1773 “she was by a direct revelation instructed to repair to America” to establish “the second Christian Church.” (It was also revealed that the colonies would win the coming war and that “liberty of conscience would be secured to all people.”) With seven followers (including her soon to be ex-husband and brother), Mother Ann, as she was now known, came to New York in 1774 and eventually settled in the wilderness a few miles northwest of Albany. Their numbers swelled in 1780 when seekers from a Baptist religious revival in nearby New Lebanon found them and then brought others to hear Ann Lee speak, and then to remain as part of the community. But their troubles weren’t over. Accused of being “unfriendly to the patriotic cause,” several of their number, including Mother Ann, were jailed in Albany until December 1780, when they were finally pardoned by Governor George Clinton. Mother Ann died at Watervliet in 1784 at forty-nine, on the land she had first settled, but the society she began continued to thrive.

Teed would have found much to admire and ponder about the Shakers at Mount Lebanon. Like him, Ann Lee had been the Second Coming of Christ. She had received no special instruction about the earth being hollow and people living inside the cosmic egg, but she too believed God has a dual male and female nature. Like the Harmonists, the Shakers practiced communalism as it seemed to derive from the primitive church, were celibate, and believed in equality of the sexes—all ideas that Teed incorporated into his Koreshan community. Like the Quakers, the Shakers were pacifist nonresisters. Two things chiefly set them apart. One was their spiritualism. “We are thoroughly convinced,” wrote Shaker Elder George Lomas in 1873, “of spirit communication and interpositions, spirit guidance and obsession. Our spiritualism has permitted us to converse, face to face, with individuals once mortals, some of whom we well knew, with others born before the flood.”

41 The other was their exuberance when this spirit struck them. In the main, their services were sober and restrained. But when the spirit moved—shaking, quaking, talking in tongues, ecstatic screaming, foaming at the mouth, jerking with convulsions, rolling about the floor, and swooning weren’t unheard of. Teed didn’t incorporate such flamboyance into his church. But he did take inspiration from the Shakers’ orderly prosperity. Like the Harmonists, the Shakers had created a self-contained, self-sustaining community. Unlike the Perfectionists led by John Humphrey Noyes at Oneida, New York, whose economic success lay primarily in manufacturing—Oneida was built on a better bear trap of their invention and handsome flatware—the Shakers did it mainly through agriculture, plus a few small cottage industries. Teed duly noted this profitable mixture.

Around this time Teed’s parents had relocated to Moravia at the southern tip of one of the lesser Finger Lakes, where they had started a mop-making venture, and invited him to work at it with them, probably hoping to distract him from the arcane religious notions his Baptist father didn’t accept. Teed joined them but continued to pursue his interest in religion. With a small number of followers he established the first of his celibate Koreshan communities. He adopted the name Koreshanity for his beliefs and renamed himself Koresh (Cyrus in Hebrew). Both the mop business and the communal venture in Moravia failed after two years. “He alienated the residents of the town,” according to Howard D. Fine, “and moved his community to Syracuse. There he established the Syracuse Institute of Progressive Medicine. In circumstances similar to those of his earlier move, he and his followers left Syracuse for New York City in the mid-1880s,”

42 ahead of charges by Mrs. Charles Cobb that Teed had defrauded her (and her mother) out of a sum of money by claiming he was the new messiah. It seems to have been a case of heated religious enthusiasm burned to cold ashes, but the publicity was enough to force Teed to pack up and leave town, in such pinched financial circumstances that he had to ask his friend Dr. Andrews for a loan to do so. A

New York Times account of the Cobb business also said that while in Moravia Teed had encouraged the wife of a liveryman to run off with him, and that

that small scandal had made moving to Syracuse seem like a very good idea to him.

In New York City Teed established another modest commune, this time in a third-floor walkup apartment on 135TH Street near Eighth Avenue, where he was living with four women (two being his sister and his cousin). He was forty-six years old and had been the new messiah of the hollow earth for sixteen years, but he was unable to sustain even this little enclave.

Everything changed in 1886. The National Association of Mental Science was holding a convention in Chicago in September, and Teed got an offer to give an address. Once again, an enthusiastic woman was involved. Mrs. Thankful H. Hale, a member of the convention, had heard Teed in New York and urged the organization to bring him to Chicago to speak—all expenses paid by Mrs. Hale. Teed jumped at the chance. His speech was apparently such a barn burner (the text doesn’t survive) that he followed it the next day with one on the brain.

The brain lecture concluded with faith healing, and a woman so fat she could hardly walk made it home on foot. Teed was a hit. He soon moved to Chicago, using the association as a springboard for his many plans and schemes. Soon he had established a metaphysical school called the World College of Life. Its first graduates in June 1887 were fourteen women, who had earned Psychic and Pneumic Therapeutic Doctorates, making them, it seems, Ph.D.s in brain and soul therapy. He also set up the Guiding Star Publishing House to get the word out, beginning the first of a long torrent of Koreshan publi-cations. The monthly Guiding Star (“a magazine devoted to the science of being”) commenced in December 1886. It became the more kinetic Flaming Sword in November 1889. And, of course, he started a church, the Assembly of the Covenant (Church Triumphant). Chief among the church leaders, theoretically coequal with Teed, Mrs. Annie G. Ordway (yet another Mrs.) was named Dual Associate, and later rechristened Victoria Gratia. Teed had been promised a feminine counterpart during his illumination, and Mrs. Ordway filled the bill. She remained a close associate to Teed until his death—too close, some thought, as she was persistently rumored to be his mistress as well.

Mrs. Annie G. Ordway, Teed’s alter ego and coleader of the Koreshans. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

He had at last begun to attract more followers, most of them women, educated, middle-class, married. It is hard to understand at this distance how he gained any converts to the idea that we’re all living inside the concavity of a hollow earth. Indeed, it is hard to understand why the hollow earth business was such an important part of Teed’s creed in the first place. Possibly the women just thought it an incidental quirk, forgiving this further evidence of male weirdness, focusing instead on his belief in a male/female God, his insistence on equality of the sexes, and a peaceful life of chastity outside the dungeon of marriage. By this time he had also added another appealing promise—his followers would enjoy personal immortality. Possibly, too, it was a certain sexy charisma on Teed’s part. He wasn’t big, about 5’6” and 165 pounds, but he had square-jawed good looks, a deep resonant voice, and an unwavering focus to his eyes usually described as “forceful” and “penetrating.”

By 1888 the number of believers had so grown that he signed a lease on “a large double brick house on the corner of 33rd Place and College [Cottage] Grove Avenue,” where he set up his largest celibate community to date.

43 The numbers continued to increase in a modest way, and four years later the core group moved into expanded quarters. By then Teed counted 126 followers in Chicago, nearly three-quarters of them women, almost all living in or near a South Side Washington Heights enclave of eight and a half acres containing a mansion, cottages, beautiful gardens and shady walks, and two ponds big enough for ice skating in the winter. They called the compound Beth-Ophra. An 1894 article in the

Chicago Herald described it as “a fine property . . . surrounded by broad, shady verandas and magnificent grounds thickly studded with old trees and made attractive by grass plats and flower beds. With . . . [Teed] in the same fine building live some of the prominent angels [of his church]. There are seven cottages besides in which other members of the Koreshan community live, and an office building—formerly a huge barn—in which is the printing office.”

44 Today this once peaceful spot lies beneath the Dan Ryan Expressway, thundered over nonstop by trucks pounding along, except during rush hour gridlock.

Eventually Teed began looking around for an unspoiled pastoral place to build a new community from scratch, where his New Jerusalem might arise. And how would he recognize the right place? It would be at “the point where the vitellus of the alchemico-organic cosmos specifically determines,” another of those recondite locutions Teed was so fond of. He also called this special spot “the vitellus of the cosmogenic egg.” By cosmogenic egg he meant the earth, and the more common word for vitellus is yolk—though here he was probably using it in the sense of “embryo.” The yolk is inside the egg, of course, its center. In other words, in Koreshan cosmology, they were seeking to locate their magnificent city at the center of the center, inside the earth.

Teed set off from Chicago in 1893 with an entourage of three women—Mrs. Annie G. Ordway, Mrs. Berthaldine Boomer, and Mrs. Mary C. Mills. They followed an itinerary set by prayer. Robert Lynn Rainard says that “each night the group sought in devotions guidance for the following day’s journey. Spiritual direction ‘guided’ them into Florida and to their ultimate destination.”

45 In January 1894, they found themselves in Punta Rassa on the southwest coast, a few miles west of Fort Myers at the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River. Today the peninsula is occupied by the Sanibel Harbour Resort and Spa near the causeway to toney Sanibel Island. Punta Rassa was a former cattle shipping town that had died after the Civil War, reborn in the 1880s as a sportfishing resort for the wealthy, complete with its own fancy hotel, the Tarpon House Inn. Teed and his attractive spiritual helpmeets were stopping there when they had a momentous encounter. Rainard says:

At Punta Rassa the Koreshans met an elderly German named Gustav Damkohler, and his son Elwin, who were on their way back from their Christmas visit to Fort Myers. Teed engaged Damkohler in conversation which led to the Koreshans being invited to visit Damkohler’s homestead at the Estero River, twenty miles down the coast from Punta Rassa. Damkohler, who had been a Florida pioneer since the early 1880s, had lost his wife in child-birth, and all but one child to the treacheries of pioneer life. A man in need of companionship, Damkohler was receptive to the fellowship of the Koreshans and the pampering of their women. At Estero Dr. Teed came to the realization that he had been directed to the remote Florida wilderness by the Divine Being.

The Koreshan Story, a more “official” account, though not necessarily a more accurate one, has this fortuitous meeting taking place differently. According to it, a prospective seller had sent Teed train tickets to inspect a property on Pine Island, Florida, just north of Punta Rassa, and in December 1893 he and the three women went to check it out. It proved prohibitively expensive, but while in Punta Gorda, Teed had taken the opportunity to give a few lectures and distribute a few pounds of Koreshan pamphlets, and some of this literature found its way to Damkohler, who wrote a letter to Teed—in German, sent in a Watch Tower Society envelope covered with biblical quotes. The Koreshan Story has it, “as Victoria Gratia (Annie Ordway) held the letter (unopened) she seemed to know that it would lead them back to Florida that winter to the right place to begin.” Back in Florida in January 1894, the momentous meeting took place in Punta Rassa. Teed lit right into expounding his doctrines, and Damkohler soaked it all in like a sponge: “Tears of joy rolled down the man’s cheek, and he exclaimed repeatedly, ‘Master! Master! The Lord is in it!’ He then besought them to come with him and see the land he had held for the Master.”

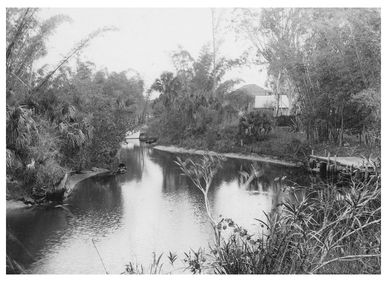

This early view of the Estero River facing east reveals the wild tranquility of the setting Teed selected for his New Jerusalem. The roof in the middle distance belongs to Damkohler’s original cottage. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

Except for their mutual religious fervor, Damkohler and Teed were a study in contrasts. Teed, sleek, meticulously groomed, given to custom-tailored suits, cultured, sophisticated, silver-tongued. And Damkohler, an aging swamp rat, though a handsome one, with forceful features, silvery hair, and an abundant white beard, lacking sight in one eye, more at home speaking German than his halting English.

Damkohler wanted them to see his land right away. They set out down the coast in a borrowed sailboat. At Mound Key they stopped for supper around a fire. Navigating through coastal mangrove thickets, they used two rowboats to make their way up the small sinuous Estero River, captivated by the wild serene beauty of the place, its solemn stillness, sand pines and cabbage palms rising more than forty feet above the placid coffee-colored river, alligators snoozing on the banks, the occasional bright chirp and chatter of tropical birds. They reached Damkohler’s little landing around ten o’clock at night on New Year’s Day 1894. The circumstances were rather more spartan than Teed was accustomed to. The only building was Damkohler’s one-room board cabin, where all camped out. As

The Koreshan Story describes their arrangements,

The cabin also had a front and back porch, but furnishings were scant. They sat on boxes to eat their meals from a broad shelf built into the back porch. The chief bed was in the cabin’s living room and was assigned to the three sisters. The ladies lay cross-wise with the tall Victoria’s feet resting on boxes along side the bed. Dr. Teed, Mr. Damkohler and the boy slept on cots and piles of old sails on the floor of the attic. This old cabin still stands in Estero today.... Dr. Teed busied himself grubbing and clearing land, while the women were occupied with improving the cabin, preparing meals and other activities about the place. For food and supplies they were obliged to row and sail to Pine Island. The river provided fish and Damkohler’s beehives produced excellent honey.

It sounds like a pleasant idyll. Teed remained three weeks before returning to Chicago, possibly because Damkohler needed additional convincing when it came to turning over the land. Damkohler seems to have been ready to give the Koreshans half his 320 acres, but Teed was urging him to deed over the other half as well—for a token price of one dollar. Thrifty German Damkohler wasn’t so sure about that, but in the end he gave in. The deal they finally struck was $200 for three hundred acres, with Damkohler holding on to twenty for himself. He would later have second thoughts.

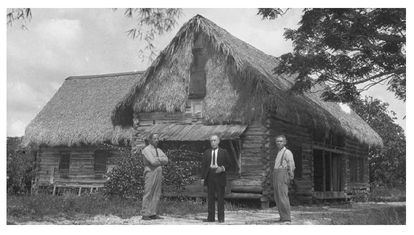

The women stayed on—their company no doubt added inducement to Damkohler—while Teed took the train back to Chicago to put together a group of recruits. A few weeks later twenty-four Koreshans arrived from Chicago and began constructing a two-story L-shaped log building with a thatched roof (known as the Brothers House) as a temporary shelter while they built the first of the community’s permanent buildings. They also put up white canvas “tent-houses” beneath groves of live oaks, with overhangs to create shady front porches with raised wooden floors and decorated with cheery trailers of flowering plants; they were big enough for a few wicker rockers and canvas deck chairs—quite inviting looking in the surviving photographs.

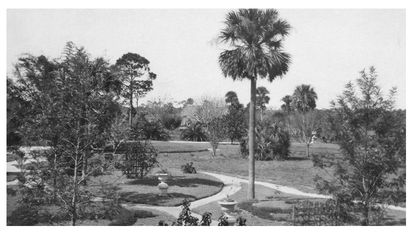

Over the next years they gradually turned Damkohler’s wilderness (he had cleared only one of his 320 acres) into a charming tidy community consisting of over thirty buildings, extensive gardens, and pleasing walkways laid out in a radial pattern from the community’s center. Estero never became the mighty megalopolis of Teed’s dreams. It was to be, he wrote, “like a thousand world’s fair cities. Estero will manifest one great panorama of architectural beauty . . . Here is to exist the climax, the crowning glory, of civilization’s greatest cosmopolitan center and capital . . . which shall loudly call to all the world for millions of progressive minds and hearts to leave the turmoil of the great time of trouble, and make their homes in the Guiding Star City.” Estero would be the primary city on earth—or rather

in it—with a population of 10 million. His plan called for a star-shaped radial geometry reminiscent of Pierre L’Enfant’s graceful design for Washington, DC, boasting grand avenues four hundred feet across, “with parks of fruit and nut trees extending the entire length of these streets,” as an 1895 Koreshan publication describes it. It continues:

The construction of the city will be of such a character as to provide for a combination of street elevation, placing various kinds of traffic upon different surfaces; as for instance, heavy team traffic upon the ground surface, light driving upon a plane distinct from either, and all railroad travel upon distinct planes, dividing even the freight and passenger traffic by separate elevations. There will be no dumping of sewage into the streams, bay or Gulf. A moveable and continuous earth closet will carry the ‘debris’ and offal of the city to a place thirty or more miles distant, where it will be transformed to fertilization and restored to the land surface to be absorbed by vegetable growth. There will be no smudge or smoke. Power by which machinery will be moved will be by the utilization of the electromagnetic currents of the earth and air, independently of steam application to so called ‘dyanmos.’ Motors will take the place of motion derived from steam pressure. The city will be constructed on the most magnificent scale, without the use of so called money. These things can be done easily once the people know the force of co-operation and united life, and understand the great principles of utilization and economy.

46

Brothers House, one of the first structures the Koreshans built on the tangled Florida wilderness they bought from Gustav Damkohler. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

Koreshan manicured grounds, with walkways meandering through beautiful plantings and the occasional stone urn overflowing with flowers in bloom—truly a garden in the wilderness. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

Futurama! The multiple divisions of the roadway seem unduly complicated, but the ecological concern shown here is definitely enlightened for the time, even if it’s hard to envision the continuously moving “earth closet.” Not dumping sewage into waterways and recycling for fertilizer were practically unheard of then. And proclaiming “no smudge or smoke” is definitely utopian, as is the plan to achieve it by using a new Koreshan form of clean energy—“the electromagnetic currents of the earth and air.” Ditto accomplishing all of this “without the use of so called money”!

Estero never quite got that far, but in its prime it was pretty nice, if decidedly smaller and more homey than it appeared in Teed’s fertile imagination. As a visiting Shaker described it around 1904:

The buildings are mostly set in a park along the right bank of the Estero River for about a mile. This park contains sunken gardens filled with flowers, banana trees loaded with fruit, paw-paw trees in fruit, palm trees of many varieties, the tall and stately eucalyptus, the bamboo waving its beautiful foliage, and many flowering trees and shrubs. Mounds are cast up, and crowned with large urns or vases for flowering plants. Steps lead down into the sunken gardens and to the water’s edge at the river. This land, where the park and the buildings are located, was at times swallowed with water before the Koreshans came. They expended $3,000 or more in dredging the river, besides making a deep ravine to carry off the surplus water into the river. The ravine is now beautified with Para and Guinea grasses, both native of Cuba, and is crossed by several artistic foot-bridges made of bamboo and other woods. Almost every kind of tropical fruit possible to grow in Florida can be found in this delightful garden, flowering vines cover the verandas of the houses and the foot-bridges in the park. Steps leading down to the boat landing, made of concrete colored with red clay, are quite grand, and were made and designed by the brethren. In fact, all the work in this magnificent garden is the product of home brains and industry. Koresh says he intends parking the river on both sides down to the bay, a distance of five miles.

47Shortly after 1900, at its height, Estero had a population of about two hundred people, who engaged in all sorts of self-sustaining enterprises. Among the first of these was a Fort Myers sawmill they bought in 1895 and moved to nearby Estero Island, where they produced lumber both for their own construction purposes and for sale to others. Members working the mill also built houses on the island, and soon there was a small satellite colony there. A substantial three-story dining hall went up in 1896, with a large eating area on the first floor (where seating arrangements were sexually segregated), while the floors above served as dormitories for the “sisters.” Next came the Master’s House, a snazzy residence for their visionary leader, along with structures to serve their many cottage industries. They also had their own post office, and the general store they opened where the Estero River crossed the trail that would become Route 41 did a brisk business. (The old frame building is still standing, just off the highway, seeming to cringe from the traffic roaring by.) The Koreshans were a busy, productive bunch.

One of the most ambitious Koreshan buildings at Estero was Art Hall, which included an expansive stage where plays, concerts, and musicales were regularly performed. Music and art were important to the Koreshans, as were aesthetics of every sort. Those ornamental urns set on mounds around the property, aglow with flowering plants, were emblematic. Nearly everyone was musical in some way. The Koreshan orchestra gave weekly concerts at Art Hall, and the brass band took first prize at the state fair one year—an expensive pair of well-bred horses. “Victor concerts” were another musical diversion. One of the female members had a collection of two hundred or so records, and getting together ’round the old Victrola was a popular pastime. “Picnics were frequently organized and held in the woods around Estero, or on one of the islands in the bay,” writes Elliott Mackle Jr. “These were ‘enlivened with music by the band, speeches, jokes, and the playing of various games’ . . . Pleasure boating added to the enjoyment of life at Estero, and moonlight cruises were often organized. Assembling the brass band in one boat, the Koreshans would follow in others, music filling the night as the little flotilla cruised up the river and around the bay. There were, in addition, fishing and hunting expeditions, classes, rehearsals, and trips to various points of interest in the area.”

48

Koreshan children dressed in costumes, standing in front of the Tea House. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

They also had a little riverside outdoor theater. As Carl Carmer, a

New Yorker writer who visited Estero in 1948, describes it in

Dark Trees to the Wind, They built a floating stage at a bend where the river had made from its banks a natural amphitheater and there they played dramas by Lord Dunsany and other modern playwrights . . . Some evenings their string and wood-wind orchestra gave programs of classical music on the stage of their raft theater and the audience, sitting under the palms beside the star-reflecting river, found life as good as they had thought it would be when they left their northern homes to follow Koresh.

49Sounds pleasant, doesn’t it? Almost utopian. The peaceful scenes Mackle and Carmer depict go a long way toward explaining why these two hundred or so people were willing to leave Chicago and follow Teed into the Florida wilderness—even given his peculiar messianic hollow earth theology. Koreshanity, and Estero as its physical incarnation, provided sanctuary. Teed’s belief that we are living inside the earth, beyond which there is nothing, can be seen as a sort of ultimate metaphysical retreat to the womb—the entire universe as a small enclosed protective egg, finite, comprehensible, safe. And in the later innings of the nineteenth century, there was a lot to retreat from.

Teed’s illumination had come in October 1869, just four years after the Civil War ended. Teed had seen its horrors firsthand as a member of the medical corps. Reconstruction and the fate of freed slaves was not a pretty picture, and President Grant’s administration set new standards for incompetence and corruption. The transcontinental railroad, completed in May 1869, seemed a tangible symbol of the way things were racing along. That it had been “financed by a group of crooked promoters who hired Congressmen to do their bidding” was a sign of the times as well.

50 America had been largely rural in 1860, and businesses were mainly farms and small private enterprises. But in the 1870s and 1880s, greed, materialism, and the application of Darwinism to the social fabric inspired the first of the robber barons to suit up and begin constructing the vast impersonal corporate trusts that would dominate the American economy by 1900, amassing profits in the multimillions while their factory workers living in grimy cities grubbed along at sixteen-hour days for crummy wages. Darwinism itself seemed the second hit of a one-two punch after Copernicus had eighty-sixed the formerly supreme earth and its solar system to an obscure corner of an obscure galaxy; now in 1871 Darwin announced that we were all descended from monkeys. Teed’s theology repudiated both these assaults on human self-esteem.

The primarily Anglo ethnic makeup of the United States was being altered as Germans, Italians, and Eastern Europeans poured in—nearly 12 million between 1870 and 1900, and this out of a total population in 1900 of 76 million. Overcrowded Italy alone provided over 650,000 immigrants, two-thirds of them men, between 1890 and 1900. These new arrivals sent cultural jolts through the formerly homogeneous communities where they settled, as well as giving unwanted competition for jobs. Most landed in cities; between 1880 and 1900 urban populations grew by 16 million. The cities became noisy, overcrowded rats-warrens, darkened by smoke, painted black by coal dust. The Koreshans knew about this firsthand, having lived in Chicago for ten years before moving to Estero. It was also a period of political upheaval, bracketed by the assassination in 1865 of Lincoln and President McKinley’s 1901 shooting at the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition by anarchist Leon Czolgosz, with the assassination in 1881 of President Garfield by that infamous Disappointed Office Seeker in between. Garfield himself had commented on “the general tendency to fast living, increased nervousness, and the general spirit of rush that seems to pervade life and thought in our times.” Much of the upheaval during this time was fueled by economic problems, the two largest manifestations being the Panic of 1873, which dragged into a prolonged depression, and the worse Panic of 1893, whose effects were being felt even as Teed negotiated with Damkohler for his remote Florida land. Nearly a fourth of the country’s railroads went bankrupt, and in some cities, unemployment hit 25 percent. The so-called Coxey’s Army of disgruntled unemployed workers marched on Washington, arriving on April 30, 1894, and briefly camped out under the Washington Monument before the leaders were arrested and the others dispersed. Not two weeks later, workers for the Pullman railroad car works in Chicago—only a few miles from Teed’s South Side headquarters—went on strike and were soon joined by 50,000 sympathetic rail workers who refused to handle Pullman cars, which promised to shut down the nation’s rail system. Federal troops were called in to keep the trains moving, as rioting, bloodshed, and looting broke out in Chicago. On July 6, several thousand rioters destroyed seven hundred railcars, to the tune of $340,000 damage, and the next day a fire demolished seven buildings at the Columbian Exposition. National Guardsmen were assaulted and fired into the crowd, killing or wounding dozens. And all of this practically in Teed’s backyard.

So to Teed’s adherents, sitting about on a soft warm evening listening to a string quartet down by the riverside beneath the palms probably seemed like the best place to be. It was a peaceful existence, far from the turmoil of what passed for modern life elsewhere. “They saw a world in chaos,” writes Robert S. Fogarty in his introduction to a 1975 reprint of Teed’s The Cellular Cosmogony, “with force and greed central elements in that universe; therefore, they constructed a static world that closed in on itself, denied progress and affirmed man’s place in that world. Cyrus Reed Teed may have been a lunatic, a fraud, and a swindler; however, to his followers he was Koresh, the prophet whose philosophy was a divine mandate to cultivate the earth and save it for future generations.”

Teed hadn’t forgotten about the hollow earth. Starting in 1896, after his little colony was well established in Florida, he began orchestrating a series of experiments to prove scientifically his contention that we are living inside—that the earth around us is concave, not convex, as most people believed in their delusion. In 1898 he produced, in collaboration with Professor Ulysses Grant Morrow, a definitive volume combining a long section by himself about Koreshan cosmology with a detailed account by Morrow of their “geodesic” experiments. It’s revealing to reproduce the entire title page from the 1905 edition:

THE

CELLULAR COSMOGONY

…OR…

THE EARTH A CONCAVE SPHERE

CYRUS. R. TEED

PART I

The Universology of Koreshanity

(WITH ADDENDUM: “ASTRONOMY’S FALSE FOUNDATION.”)

BY KORESH

THE FOUNDER OF THE KORESHAN SYSTEM OF RELIGIO-SCIENCE; AUTHOR

OF VOLUMES OF KORESHAN LITERATURE

PART II

The New Geodesy

BY PROFESSOR U. G. MORROW

ASTRONOMER AND GEODESIST FOR THE KORESHAN UNITY,

AND EDITOR OFTHE FLAMING SWORD

Judging from the defensive tone of his introduction, it would appear that one common question asked of Teed was, Well, if we’re inside the earth like you say, and from that perspective it’s concave, why does it look convex, curving downward in the distance? And what about all those stars and galaxies that sure seem like they’re millions of miles away? Huh, Koresh?

He leaps right into refuting “that dangerous fallacy, the Copernican system”:

Deity, if this be the term employed to designate the Supreme Source of being and activity, cannot be comprehended until the structure and function of the universe are absolutely known; hence mankind is ignorant of God until his handiwork is accurately deciphered. Yet to know God, who, though unknown by the world is not ‘unknowable,’ is the supreme demand of all intellectual research and development.

If we accept the logical deduction of the fallacious Copernican system of astronomy, we conclude the universe to be illimitable and incomprehensible, and its cause equally so; therefore, not only would the universe be forever beyond the reach of the intellectual perspective of human aspiration and effort, but God himself would be beyond the pale of our conception, and therefore beyond our adoration.

The Koreshan Cosmogony reduces the universe to proportionate limits, and its cause within the comprehension of the human mind. It demonstrates the possibility of the attainment of man to his supreme inheritance, the ultimate dominion of the universe, thus restoring him to the acme of exaltation—the throne of the Eternal, whence he had his origin.

This is sweet, really. Copernicus can’t be true because his theories produce an unfathomable, limitless universe we humans cannot understand; God wouldn’t do that to us because then we couldn’t understand him. Koreshan cosmogony restores us to our true and rightful place—the center of the universe, sitting on the throne of the Eternal, right where we belong. The demotion we all suffered thanks to Copernicus regarding our importance, locationwise, continues to sting. Teed rectified that by returning us to the center of things, albeit inside them. In this regard and others, Koreshanity was deeply conservative.

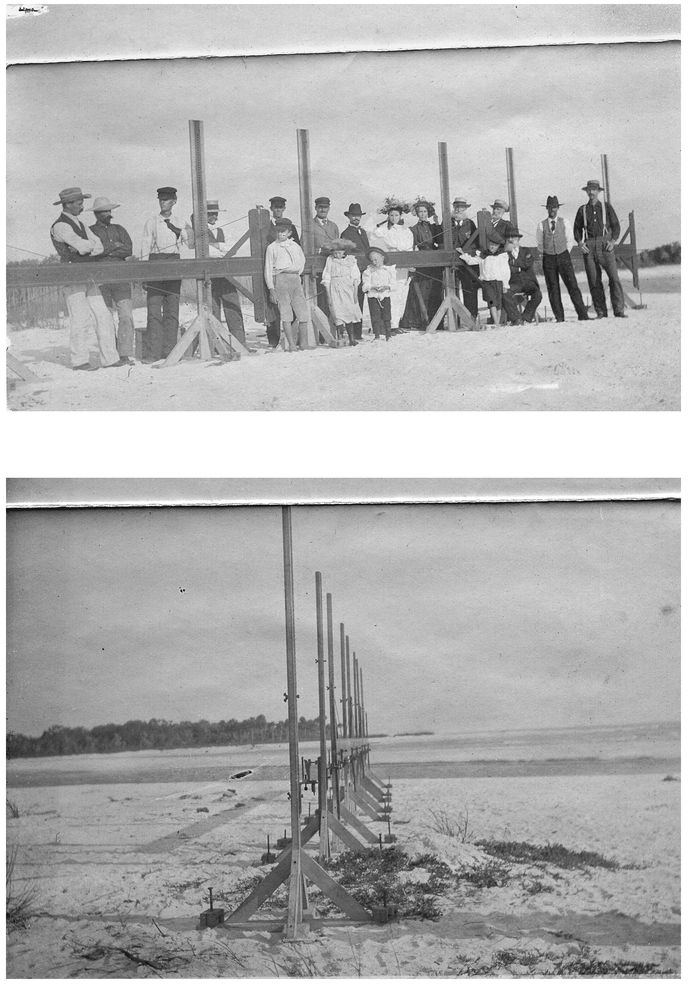

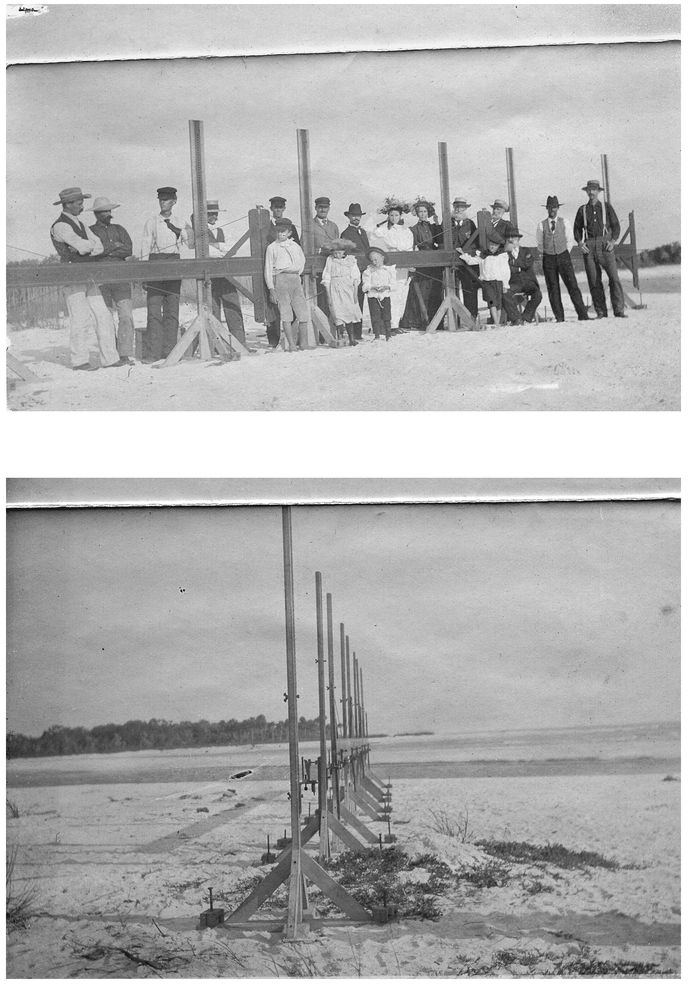

Next he says that he established the “cosmogonic form” of the universe, which he “declared to be cellular,” determining that the surface of the earth is concave, with an upward curvature of about eight inches to the mile. Even though he ascertained all this with theoretical rigor, still people scoffed. What else for this avatar of “religio-science” to do but conduct experiments proving his theory true? He says, “The suggestion urged itself that we transpose, from the domain of optical science to that of mechanical principles, the effort to enlighten the world as to cosmic form.” The idea was simple. If the earth’s curvature were convex, a straight line extended for any distance would touch at only one point; but if it were concave and the line long enough, it would eventually bump into the upcurving surface. So Professor Morrow invented the Rectilineator. As he described it in

The Cellular Cosmogony: The Rectilineator consists of a number of sections in the form of double T squares [|————|], each 12 feet in length, which braced and tensioned cross-arms is to the length of the section, as 1 is to 3. The material of which the sections of the Rectilineator are constructed of inch mahogany, seasoned for twelve years in the shops of the Pullman Palace Co., Pullman, III.

Visitors to the Koreshan State Historic Site can still see a section of it inside Art Hall, sun-bleached and dusty, leaning against the back of the stage. Morrow and some fellow religio-scientists had tried a few tests in Illinois, along the shore of Lake Michigan on the grounds of the Columbian Exposition and on the Illinois & Michigan Canal between the Chicago and Illinois rivers, but neither provided the requisite uninterrupted spaces needed. The plan was to construct a perfectly straight line . . . four miles long.

Koreshan experiment involving the Rectilineator. (Koreshan State Historic Site)

This experiment was another reason Estero attracted Teed. Florida’s Gulf Coast then offered endless empty beaches stretching for miles. In January 1897 they began the undertaking near Naples because the coast there offered the needed distance. They set up shop in Naples at a beachfront enclave belonging to Colonel W. N. Haldeman, owner/publisher of the Louisville

Courier Journal, which says something about Teed’s connections. The Rectilineator sections were transported from Estero in the

Ada, a small sloop Teed had acquired in 1894. Work on the experiment continued until May. After an “air line” was established, segments of the Rectilineator were meticulously aligned and connected, the trailing section then removed and carefully attached to the front, the lengthy double T square apparatus laboriously hopscotching along the beach while measurements were constantly made. By April 1 they’d gone one mile and by April 16 two, but they took until May 5 to make it another half mile. Elliott Mackle Jr. describes the progress from there:

On May 5, another half mile had been covered and the line’s distance from the fixed water line was 54 inches closer than at the beginning, a difference of 4 inches from calculation. At this point, however, the beach curved away and, in any case, the vertical bar of the double T square was within seven inches of the ground, and so it was necessary to employ another method of survey. Using telescopes, poles in the water, and the sloop Ada, the line was projected another mile and five-eighths on May 5 and repeated on May 8. Return surveys were performed on May 6 and 11. This projected line met the water four and one-eighth miles from the starting point, indicating to Morrow that the earth’s surface had curved upward 128 inches . . . the earth had, according to the terms of his experiment, curved upward, proving the validity of the cellular theory.

The care and precise exertion involved were prodigious, although surviving pictures suggest they had fun while they were at it. Needless to say, their efforts were rewarded—as Professor Morrow attests for a dense 140 pages or so in The Cellular Cosmogony. They determined the earth’s concavity to their complete—and scientific—satisfaction.

Things at Estero sailed along serenely for the next few years except for a couple of blips. The first came from Gustav Damkohler. In 1897 he sued to get his land back. The reasons are a little obscure. He may have believed that Teed promised him a fine house in the community’s center that never materialized. If so, he probably got increasingly peeved as he watched the impressive residence for Teed and Mrs. Ordway (where they would presumably live together in cozy chastity) going up. Damkohler got fed up with Teed and his grandiose plans and took him to court. He found a clever lawyer who used an ingenious gambit—placing the Koreshans’ unconventional beliefs into evidence, essentially trying to get a judgment against them for their odd views.

But Teed understood public relations and from the start had gone out of his way to be sure his Estero community was both friendly and accommodating to its neighbors, especially people in growing Fort Myers, fourteen miles to the north. It paid off. The lengthy trial commenced in April 1897 but was eventually settled out of court. Damkohler got half of his original 320 acres back, but none that affected the Koreshan community.

Koreshan leadership at Estero, probably in the late 1890s, with Cyrus Teed and Mrs. Annie G. Ordway front and center. Note the ceremonial faux medieval halberd bearers on either side.

A considerably more flamboyant attack came the next year, swooping down on them in the form of Editha Lolita, one of the many names and titles she trailed behind her like a long feather boa. According to Rainard, “She claimed to be the Countess Landsfeld, and Baroness Rosenthal, daughter of Ludwig I of Bavaria, and Lola Montez, god child of Pius IX, divorced wife of General Diss Debar, widow of two other men, bride of James Dutton Jackson, and the self-proclaimed successor to the priestess of occultism, Madame Blavatsky.”

51 She showed up in southwestern Florida with current hubby Jackson, whom she’d married in New Orleans on November 13, 1898, her maiden name listed on the official marriage record as Princess Editha Lolita Ludwig. Knowing nothing about him, we would have to suppose James Dutton Jackson a brave man. Editha had come to Florida to establish her own backwoods utopia, the Order of the Crystal Sea, on several thousand acres Jackson apparently owned in Lee County—where they would all live on fruits and nuts (appropriately, Rainard notes), while kicking back to await the millennium. But this was near the Koreshan community, and Editha Lolita decided there wasn’t room for two utopias in one county. She launched into attack mode against Teed and his followers, adroitly using the

Fort Myers Press as her chief outlet for innuendo and abuse, expressing her shock that a “scoundrel” like Teed could be permitted to live among the decent folk of Fort Myers. “Day after day,” says Rainard, “she reported to the

Fort Myers Press stories of Teed’s allegedly sordid past.” This went on for months. When the Koreshans decided enough was enough, they revealed to the Fort Myers paper that Editha had been a Koreshan in Chicago but left and then tried to break up the community in ways that had drawn the attention of the police and the Chicago newspapers. In a follow-up story Editha Lolita admitted belonging to the Chicago enclave but had only joined them, as Rainard says, quoting her, “after she had been ‘released by the Jesuit priest’ who had ‘kidnapped her.’” Not long after these revelations, Editha Lolita and her husband faded out of the picture, heading on to greener delusional pastures elsewhere.

Estero was calm as the new century began. Its population dropped to twenty-eight at one point, in part because Teed had returned to Chicago to begin closing out the operation there, while his esteemed counterpart, Victoria Gratia, was in Washington, DC, helping set up a new Koreshan colony in the heart of the beast. The last of the Chicago crowd moved lock, stock, and fifteen railway cars full of stuff to Florida in 1903, raising the population to around two hundred—hardly 10 million, but not bad. Everything was peachy at Estero until 1904 or so. Their various enterprises were humming along, and all was going so well that Teed decided to incorporate as a town, mainly because it would qualify them for tax money to improve the roads. This first step into the local political realm proved to be the beginning of the end. Non-Koreshans in the lightly populated county were understandably apprehensive about the influence of this relatively large group of people, all of whom were pledged to vote in a bloc. Pronouncements such as “I am going to bring thousands to Florida . . . and make every vote count in Florida and Lee County,” reported in the increasingly hostile Fort Myers Press, didn’t help. Also, Fort Myers—or at least the newspaper—began feeling it might have more to lose after the railroad was extended there in 1904, and dream balloons of great growth and prosperity began inflating. They didn’t want a bunch of crazy hollow earthers spoiling their prospects.

The editor of the Fort Myers Press, Philip Isaacs, played a major part in what followed. He had political ambitions and offered Koreshans a weekly news column (written by Rectilineator inventor U. G. Morrow) in exchange for a pledge to vote for him for county judge in the 1904 Democratic primary and general election. They kept their end of the bargain, and he was elected. This was back in the heyday of the “solid South,” meaning solidly Democratic. But the election of 1906 proved more troublesome. It became known that in 1904 the Koreshans had defected from the Democratic party and voted as a group for Teddy Roosevelt, though he was the only Republican they voted for. This peeved local Democrats, who came up with a scam to bar them from voting in the 1906 Democratic primary—a pledge each voter was required to sign affirming that he had supported all Democratic candidates in 1904. The Koreshans, not easily scared off, simply amended the pledge before signing it and voted anyway.

The Democratic Committee, chaired by Philip Isaacs, then proceeded to toss out all votes from the Estero precinct. Okay, said the Koreshans, watch this. They announced they would support non-Democratic candidates in November and set about putting together their own new Progressive Liberty party, in which, Elliott Mackle Jr. says, “Koreshans, Socialists, Republicans, dissatisfied Democrats, and other dissidents (but, notably, not Negroes) could band together in opposition to the Democratic organization.” Since they couldn’t hope to get fair coverage from Isaacs’ paper and since they had the equipment handy anyway, they started their own weekly newspaper, the American Eagle, in June 1906. The first issues were almost entirely devoted to politics, both stumping for the candidates they were endorsing and pounding on the incompetence and corruption of their opponents. A main target, not surprisingly, was Philip Isaacs. Naturally the Fort Myers Press blasted right back. The Progressive Liberty party began staging political rallies in various towns around Lee County, bringing along the Koreshan brass band to churn up enthusiasm and get everybody in the mood for the speechifying.

By October tempers on both sides were getting frazzled, and a disputed telephone call triggered an ugly encounter like something out of the Old West orchestrated by Monty Python.

52 It began when W. W. Pilling arrived in Fort Meyers on his way to join the Koreshan community. Finding no one there to pick him up, he sent a note to Estero and repaired for the night to a hotel belonging to a Colonel Sellers and his wife. The next morning someone called from Estero asking for him but was apparently told by Mrs. Sellers, “He is not here.” What she meant by that wasn’t made clear to the caller—whether he was still upstairs, or out, or what. She definitely did

not mean that he wasn’t registered there, a point that didn’t get through to the Estero caller. During a second call later in the day, when Mrs. Sellers said she would get Pilling, the caller said, “I thought you told me no one by that name was stopping there.” Pilling later said that Mrs. Sellers didn’t seem upset by this exchange.

Two weeks later, W. Ross Wallace, a Koreshan, and the only one running for office in the election, was accosted by Colonel Sellers on a Fort Meyers street. Sellers accused Wallace of calling Mrs. Sellers a liar, and, without waiting for a reply, began beating on him. Wallace tried to defend himself and begged the mayor of Fort Myers, who was standing nearby impassively watching this, for help, which wasn’t forthcoming. Wallace prudently fled. One week later, on October 13, Cyrus Teed, dressed as always in a spiffy black suit, was in town to meet a group of new Koreshans arriving by train from Baltimore. As he was walking down the street toward the station, he encountered Wallace, Sellers, and town marshal S. W. Sanchez in front of R. W. Gilliam’s grocery store. They’d gotten together to discuss Sellers’ attack—though why they were doing so on the street is a good question. Wallace was explaining that he was out of town campaigning on the day in question and couldn’t have been the caller. Sellers was saying that wasn’t what he had heard when Teed walked up to them and jumped into the discussion, offering that people often misunderstand telephone conversations but then repeating what people in Estero had overheard their caller saying.

“Don’t you call me a liar!” exclaimed Sellers, slugging Teed three times in the face, whap! whap! whap! Like the mayor before him, the town marshal stood there watching, making no move to stop it. Teed raised his hands to protect his face without fighting back. Sellers pulled a knife, but someone grabbed his arm and persuaded him to put it away.

Any good fight draws a crowd. Meanwhile, the train had arrived, and the Koreshans, including several young men, came upon this scene. Estero resident Richard Jentsch, seeing Teed being pummeled, slugged Sellers and was knocked down by the crowd for his trouble. Then the boys jumped in, fighting until they were bloody and their luggage dumped into the gutter.

Marshal Sanchez at last leaped into action, grabbing Teed by the lapel and shouting, “You struck him and called him a liar!”

“I did not strike him, nor call him a liar,” said Teed.

“Don’t tell me you did not strike him,” said Sanchez, slapping Teed across the face and knocking off his glasses.

Sanchez then grabbed Teed and one of the Baltimore Koreshans, telling them they were under arrest. At this moment irrepressible Jentsch, somehow shaking loose from the crowd, threw himself at Sanchez and landed a good punch. Taking his nightstick to Jentsch, Sanchez hissed, “You hit me again and I will kill you!” clubbing him repeatedly until he fell to the ground. Placing Teed, Jentsch, and Wallace under arrest, Sanchez hauled them off to jail, where each had to post a $10 bond for a court appearance the next Monday—an appearance none of them, sensibly, ever showed up for.

Fort Myers politics, circa 1906.

Teed never recovered fully from this beating. His Progressive Liberty party didn’t win a single office, but some candidates drew over 30 percent of the vote—a respectable showing given that in previous elections Democratic candidates had a virtual lock on winning. The PLP vowed they’d get ’em next time but didn’t. Teed withdrew from public view and spent the winter of 1906–1907 writing a

novel. Its title was

The Great Red Dragon, or, The Flaming Devil of the Orient, a book at once millenarian (no surprise there), anticapitalist, and apocalyptically racist (the bad guys are an invading Oriental army). Elliott Mackle Jr. summarizes the plot as follows:

The leaders of capitalism and of western governments unite in agreement to enslave the masses, thus ensuring higher profits for themselves. The masses within the United States are organized by a partially-messianic general to meet this threat, and the forces of the capitalist-dominated United States government and its allies are eventually brought to terms. Japan, in the meantime, at the head of a Chinese horde, has begun a conquest of the world. Rome and Russia have been laid waste, and the Oriental forces, threatening to encircle the world, have gathered off all the coasts of the United States. The American navy is defeated, America begins to fall to the invaders, and the army of the masses—the only bulwark between Western civilization and Oriental savagery—withdraws to northern Florida. The Orientals are eventually defeated by an aerial navy of “anti-gravic” platforms which fire ball bearings upon the invaders. By the use of the platforms, which were manufactured at Estero, together with high ideals and truth, the forces of righteousness conquer the world. Assisted by a beautiful young woman, the triumphant leader of the masses ushers in a new dispensation. The Divine Motherhood rules over this dispensation—she is the duality of the miraculously unified leader and his assistant. Peace and tranquillity reign in the perfected New Jerusalem. And the world follows principles identical to Koreshan Universology.

By 1908 Teed had returned to his usual busy schedule, although he was in constant pain; the beating he suffered in 1906 caused lasting nerve damage that made his left arm ache, sometimes excruciatingly so. In May he and Mrs. Ordway went to Washington, DC, and spent the summer helping the new colony there, probably in part because even muggy Washington was more comfortable than summertime in pre-air-conditioning Florida. The Koreshans participated in the political activity leading up to the fall elections, but in a subdued way. When Teed and Mrs. Ordway returned to Estero in early October, he was clearly in decline. For the first time Mrs. Ordway prayed for him before the gathered assembly; there was no longer an attempt to keep his condition secret. Gustav Faber, a Koreshan living in Washington State who was a nurse during the Spanish-American War, came all the way to Estero to care for him. Teed was moved to La Partita, a house the Koreshans had built on the southern tip of Estero Island, and there Faber gave Teed saltwater baths and tried to cure him with an “electrotherapeutic machine” he had invented.

53 During these last days, Teed was heard to exclaim, “O Jerusalem, take me!”

He died at this island cottage on December 22, 1908.

Teed had preached reincarnation and, beyond that, physical immortality for himself. He claimed to be capable of what he called theocrasis, “the incorruptible dissolution of the physical body by electro-magnetic combustion.” This is yet another of his opaque coinages and definitions, but it seems to mean that through this mysterious electromagnetic combustion, his body would renew itself. He would come back!

His more devout believers were certain this was true—and wouldn’t Christmas, three days later, be perfectly apt? They refused to bury him, and his body was returned to Estero, where it was placed in state and the vigil began. Christmas came and went, and Teed’s body was showing no signs of reviving. To the contrary, it was beginning to get pretty ripe in the unseasonably hot weather. Health officials from Fort Myers showed up, took one look, pronounced him dead, and insisted that he be buried immediately. A simple concrete tomb was prepared on Estero Island, and Teed was interred there. Some of the more fanatical believers, however, were unsatisfied with this outcome, and one dark night tried to break into the tomb to get a look, convinced he wasn’t really gone for good. A watchman was put on nightly duty. As Carl Carmer relates it:

Night after night, among the wild mangroves and the coconuts and mango trees, Carl Luettich stared into the blackness that surrounded the circle of light in which he sat. Once, just before dawn, he fell asleep and the fanatics came again and opened a side of the tomb before sunlight frightened them away. Carl Luettich was more alert after that, but watching the tomb was not necessary much longer.

This was because a hurricane and tidal wave hit the island on October 23, 1921, washing both the mausoleum and the cottage out to sea. Only the headstone was recovered, which is now on display in the auditorium of the Koreshan Unity Headquarters Building. It says simply:

CYRUS

Shepherd Stone of Israel

The aftermath of Teed’s death was a predictable scramble for power with certain black humor flourishes. Nurse Gustav Faber claimed to be Teed’s successor, saying Teed had named him the new leader with his final breaths and transferred authority through “theocrasis.” But the Estero Koreshans weren’t having it, and Faber departed early in 1909. Strangely, Teed’s longtime spiritual companion, Mrs. Ordway, had been off in Washington during Teed’s final days and didn’t make it back to Estero until December 27. She would seem his natural successor, but this was resisted, possibly by sexist elements who wouldn’t abide a woman leader, possibly because a Koreshan furniture works in Bristol, Tennessee, named for her, was going under, and the debt weighed on the community. In any case, she rather rapidly packed up and left with a few of her more dedicated followers to start up her own Koreshan commune in Seffner, Florida. It soon failed, and she married Charles A. Graves, recently mayor of Estero. They eventually settled in St. Petersburg, where she remained until her death in 1923.

The Estero community continued in diminishing circumstances for many years, until the land was finally given to the state by the last four members in 1961. The grounds are now the Koreshan Historic Site, which opened to the public in 1967. Across Highway 41 from the Koreshan Historic Site, in a modest building, the Koreshan Unity Foundation is still engaged in keeping Cyrus Teed’s legacy and ideas alive.

Teed’s tomb on Estero Island. (Koreshan State Historic Site)