The Goddess of Atvαtαbαr (1892) by William R. Bradshaw was one of many hollow earth novels that appeared toward the end of the nineteenth century. This is a map of that interior world, reached by explorer Lexington White through a convenient Symmes’ Hole at the North Pole.

6

HOLLOW UTOPIAS, ROMANCES, AND A LITTLE KIDDIE LIT

TOWARD THE END OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, the hollow earth began turning up regularly in fiction. Symmes’ famous holes were well-known, if widely ridiculed, and Verne’s A Journey to the Center of the Earth became a perennial best seller that moved the idea from the esoteric fringe into mainstream culture. Writers found it had many uses—as a handy place to set utopias, or their dark or satiric mirror opposite, dystopias; as somewhere to set improbable romances now that formerly remote, unknown corners of the earth were becoming less believable as settings the more they were explored and reported upon; and as a convenient fairyland where magical adventures could take place to amuse younger readers. Some used it for several of these ends at once.

The period between the Civil War and the beginning of the twentieth century saw the scribbling of more utopian fiction than any other time before or since. Jean Pfaelzer, in The Utopian Novel in America, 1886–1896, says that more than one hundred such fictions were written in the United States in that ten years alone. There were only a few before the Civil War—Symzonia comes to mind—because the culture hadn’t needed utopian literary productions before then. From the beginning America was seen as its own meta-utopia, one coming into actual existence. European settlers, dating back to the Pilgrims, had thought of it that way, and generations of new arrivals after them carried on the belief. If one forgot about those inconvenient Indians (and most tried to), North America’s bounteous landscape and democratic vistas were an empty canvas on which to paint actual utopian experiments. It was a perfect society aborning—the City on the Hill, a moral beacon to the world—no need to create literary counterparts.

Before the Civil War America seemed bright with this promise of perfectability, of a utopia being realized. But in the years following the war, for many, that promise shattered in bewildering, demoralizing ways. The industrialization of the United States, begun in earnest during the Civil War, went roaring on, bringing with it huge change, for better and worse. A grid of shining steel rails was being laid on the country, making movement easy in unprecedented ways. The Gilded Age (so named by Mark Twain) saw the rise of the first cyclopean corporations and the multimillionaire robber barons who headed them. Monopolies and trusts, new mutant financial creatures, ran roughshod over economic life. With all that money, corruption was inevitable, and it reached the inner sanctums of the White House. Factories multiplied like mushrooms after rain, and people poured out of the countryside to work in them, creating a huge urban laboring class that hadn’t existed before. Most worked long hours for little pay—another source of social difficulty. This population shift gave rise to big cities, with all their attendant pleasures and problems.

54 It was a qualitative change, from tranquil, uneventful village life where everyone knew everyone else, to the anonymous, crowded, uncaring, fast-paced metropolis. Waves of new immigrants were also rolling into the cities looking for work.

And the stuff these factory workers were turning out! It was a period of galloping materialism fueled by almost overwhelming technological change—telegraph, telephone, electric lights, automobiles, movies, even air conditioning—and everyone seemed to be out to get his share (or more), using whatever methods came to mind. Darwinism, chiefly as interpreted by Herbert Spencer, was being applied to the social organism, and survival of the fittest became the ringing slogan of the day (it helped the robber barons sleep peacefully at night). Forget milquetoast Sunday school lessons about loving thy neighbor and treating him as you would yourself. It was a ruthless, bloodthirsty world, and only the strong survived. Poverty simply meant you were inferior.

All of this was a long way from the America of Jeffersonian dreams. It added up to major-league culture shock on a national scale. But social upheaval, disruption, disillusionment, and confusion weren’t confined to the United States. The shock wave was worldwide. And one response writers had was to create literary utopias offering solutions to the rampant social problems they saw all around them. They began constructing ideal, alternate societies and/or dystopic satires on the evils they saw proliferating in their own. Most of these are forgotten, or nearly so, and for good reason—they were generally pretty bad. But some have lasted, most notably Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (1872) and Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward (1888). Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) can arguably be tossed in here as well, as could H. G. Wells’ still nicely creepy The Time Machine (1895). Others that haven’t quite fallen off the cultural charts into oblivion include William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890), William Dean Howells’ A Traveler from Altruria (1894), and Wells’ When the Sleeper Wakes (1899). The list of novels that only academic utopian specialists remember would run to many pages.

It was a dark and stormy night . . . inside the hollow earth.

Well, it wasn’t

really dark and stormy down there. But the writer who kicked off this thirty-year fling with utopias and dystopias inside the hollow earth with

The Coming Race (1871) is best remembered for those timelessly dopey opening words to his 1830 novel,

Paul Clifford, made famous by Snoopy at his typewriter atop his doghouse.

55Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873) was a prolific, popular author in his lifetime. Of his many books, only The Last Days of Pompeii (1834) is remembered, largely because it was filmed in 1908, 1913, 1935 (Basil Rathbone as Pontius Pilate), and 1960 (Steve Reeves as Marcus), and made into a miniseries in 1984 (Ernest Borgnine as Marcus). He was born in London as just plain Edward Bulwer and added the hyphenate Lytton, his mother’s surname, after inheriting her ancestral family manse.

Compared to the pace in Verne, the narrator in The Coming Race, an American, gets below in nothing flat. Once he is out in the well-lit, carefully groomed landscape of the inner earth, he is discovered by members of a serene, advanced civilization. They take him home and commence teaching him about their society—in fairly alarming detail.

They are the descendants of surface dwellers who fled from prehistoric floods by descending into caverns. In this The Coming Race is only a semi–hollow earth novel, in that the interior space, while vast, is a cavern system further enlarged by vril, to which they owe everything from their living space to their social perfection. It’s a versatile source of energy, both physical and mental, created from focused willpower and directed by wands that the An-ya carry—the essence of Nietzsche turned into an all-purpose laser zapper.

You name it, vril can do it: “It can destroy like the flash of lightning yet, differently applied, it can replenish or invigorate life . . . by this agency they rend their way through the most solid substances, and open valleys for culture through the rocks of their subterranean wilderness. From it they extract the light which supplies their lamps.”

Bulwer-Lytton was a politician who started out as a liberal member of Parliament in 1831 but resigned in 1841 over the government’s Corn Law policies. He returned in 1852 as a conservative Tory, and The Coming Race reflects both his political interests and his somewhat conflicted views on social ideals.

Vril has created a society of perfect harmony. No competition or ego-driven striving for power or fame. No poverty—robots do all the work. No crime. No lawyers. All worship the same Creator—there are no pointless theological disputes and religious services are short. They have flying boats and detachable vril-powered wings they use to flit from place to place. Like the Symzonians, they’re all handsome and beautiful, strict vegetarians and teetotalers, most living well beyond one hundred years. Everyone’s kind to everyone else and nobody’s rude—not even the kids (truly utopian!). The economy is a sort of laissez-faire socialism. They’ve moved beyond base, lowest-common-denominator democracy, which they consider a barbaric social structure. You can be rich and have vast estates if you feel like it. But most don’t bother, preferring to live modestly, kick back, and smell the roses. Working as an obscure artisan is as valued as being a muckety-muck, and not working at all is just fine. “They rank repose among the chief blessings of life.”

Women down here have equal rights—and then some. The beautiful Gy, as the women are called, are bigger and stronger than the men (“an important element in the consideration and maintenance of female rights”) and generally smarter, exercising a better control of vril, “her will being more resolute than his, and will being essential to the direction of the vril force.” Most work is performed by children as a form of training. One job generally given to the little girls is “the destruction of animals irreclaimably hostile” because the girls are “by constitution more ruthless under the influence of fear or hate.” The Gys initiate courtship, which leads to most of the narrator’s troubles while he’s there. One Gy named Zee falls in love with him, pursuing him so avidly it scares the hell out of him, largely because her important father doesn’t like this inferior creature from above and has plans to vaporize him with vril to eliminate the problem. At the end she selflessly helps him escape back to the surface world. He writes this book to warn people about the An-ya’s plans to come to the surface and kill humans and start over—The Coming Race of the title.

The Coming Race draws on two important ideas of the time: evolution and the emerging machine age. The An-ya are an evolutionary step ahead of surface people and have solved the problems of the nineteenth century. But their superior, rational society comes at a price, and is ultimately seen as a threat. They’re coming to get us! So is evolution, even if true, a good thing or not? Maybe not so good if you happen to be the Neanderthals and the brainy Cro-Magnons are coming. As regards the machine age, the novel suggests that science, and the technology it produces, will eliminate all difficulties. As J. O. Bailey puts it in

Pilgrims Through Space and Time, “By gaining control over such forces as electricity . . . man will establish a civilization in which there will be no toil, struggle, or poverty.” Again and again, science will be the savior, and electricity the chief instrument of salvation. It’s presented as a virtual religion in many of these novels.

56

One such is Mary Bradley Lane’s Mizora: A Prophecy. When the visitor-narrator voices shock that the inhabitants of Mizora have no religion, a resident replies, “Oh, daughter of the dark ages, turn to the benevolent and ever-willing Science. She is the goddess who has led us out of ignorance and superstition; out of degradation and disease, and every other wretchedness that superstitious degraded humanity has known. She . . . has placed us in a broad, free, independent, noble, useful and grandly happy life.”

The goddess Science has worked wonders in Mizora, but She had a little help. The critical factor in making their perfect society possible has been the total elimination of men. Mizora is all-female. Men have been extinct for 2,000 years, and with their disappearance all social ills have disappeared as well.

Mizora seems to have been the first feminist utopia—certainly the first set in the hollow earth. Originally published under a pseudonym as “The Narrative of Vera Zarovitch” in the

Cincinnati Commercial between November 6, 1880, and February 5, 1881, it didn’t appear in book form until 1890.

57 Its author was a Cincinnati housewife. The story takes its geography directly from John Cleves Symmes. The Cincinnati area was his old stomping ground, and his devoted son Americus had just written a summary defense of his father’s ideas.

The Symmes Theory of Concentric Spheres appeared in 1878, two years before Lane’s story began serialization.

As the novel opens, Vera, an aristocratic Russian, has been sentenced to life in the Siberian mines for her revolutionary opinions. Bribing her way free, she escapes northward in disguise on a whaling ship, which crashes into an ice floe and sinks in Arctic waters. She and other survivors make their way to an Eskimo encampment, but she wakes up one day to find the others in her party gone. She overwinters with the Eskimos and accompanies them in the spring as they head north to hunt. At about eighty-five degrees latitude, they come upon the open polar sea. Vera feels an overpowering desire to sail farther north on it. The accommodating Eskimos build her a boat on the spot, and she sets off.

Soon she drifts right into the closing pages of

Arthur Gordon Pym: her boat is caught in a fast current and travels in an accelerating circle, while before her rises “a column of mist,” spreading into “a curtain that appeared to be suspended in midair . . . while sparks of fire, like countless swarms of fire-flies, darted through it and blazed out into a thousand brilliant hues”—as if she’s sailing through the aurora borealis itself. Not inconveniently, “a semi-stupor, born of exhaustion and terror, seized me in its merciful embrace.” She later awakes along a broad river flowing through paradise:

The sky appeared bluer, and the air balmier than even that of Italy’s favored clime. The turf that covered the banks was smooth and fine, like a carpet of rich green velvet. The fragrance of tempting fruit was wafted by the zephyrs from numerous orchards. Birds of bright plumage flitted among the branches, anon breaking forth into wild and exultant melody, as if they rejoiced to be in so favored a clime. And truly it seemed a land of enchantment.

Some hollow earth novels are practically Cook’s tours, devoting considerable space to imaginative geographical descriptions, but Lane gives only token sketches of the landscape, brushstrokes of physical detail, little more. Mizora seems to be a large continent surrounded by a forbidding ocean; it is populated enough to have a few large cities and many towns, but these, too, are given only glancing mention. The only real indication that we’re inside the hollow earth comes early on, when Vera observes, “The horizon was bounded by a chain of mountains, that plainly showed their bases above the glowing orchards and verdant landscapes. It impressed me as peculiar, that everything appeared to rise as it gained in distance.”

Lane’s interest lies in elaborating her utopian program. Action is virtually nonexistent. Once Vera gets to Mizora, virtually nothing happens. Drama, conflict, romance, and adventure are elbowed off the stage by an endless examination of the Mizorans’ social mores and technical achievements. The only real plot question pulling a reader through the narrative is, What happened to the men? and the closely related mystery, How do you reproduce without them?

Vera encounters a boat shaped like a fish carrying Mizorans, all of whom are young, female, beautiful, and blond. Brunette Vera soon discovers that dark hair and complexions don’t exist in Mizora. Late in the novel Vera finds that just as Mizora formerly had men, some people had swarthy complexions as well. She presses her guide, the Preceptress, about this, who replies first with a policy statement: “We believe that the highest excellence of moral and mental character is alone attainable by a fair race. The elements of evil belong to the dark race.” Are these utopian Nazis? Vera asks what happened to the dark complexions. The terse reply, not elaborated on, is: “We eliminated them.”

Lane presumably does not endorse this solution, but it’s revealing that a feminist society got rid of men to achieve a state of perfection and did away with troublesome dark-skinned types as well. This was written in a time when race was arguably even more troublesome than it is today. Millions of former slaves were technically free, but Radical Reconstruction had collapsed, Jim Crow laws were created to keep blacks in “their place,” and they were facing a future filled with difficulty and hardship as second-class citizens. American Indians were being shooed west to reservations on land deemed worthless (though not without a fight—the Battle of Little Big Horn took place just four years before Mizora appeared). Millions of European immigrants were causing cultural upheaval of yet another sort. Color difference, then as now, was a huge social problem. Eliminating it entirely was a magic-wand solution, though hardly utopian. Vera’s take is that the Mizorans’ “admirable system of government, social and political, and their encouragement and provision for universal culture of so high an order, had more to do with the formation of superlative character than the elimination of the dark complexion.”

How did they achieve this social paragon?

Thousands of years ago, men ran everything and women were regarded as inferior. A revolution toppled the original aristocracy, but the new republic had one fatal flaw: a portion were slaveholders, and a civil war soon followed. Sound familiar? The war should have ended quickly, but the corrupt government prolonged it for profit. At war’s end the slaveholders collapsed and the former commander in chief of the free government, “a man of mediocre intellect and boundless self-conceit,” was made president. Could this be a parallel universe U. S. Grant? In Mizora he became a despot, assuming all the prerogatives of royalty he could manage, elevating “his obscure and numerous relatives to responsible offices.” When in a rigged election he is proclaimed President for life, all hell breaks loose. Soldiers called out to protect the government refuse to do so, chaos and faction reign.

Now, up until this point, women had been kept out of government. But in this anarchic time, “they organized for mutual protection from the lawlessness that prevailed. The organizations grew, united and developed into military power. They used their power wisely, discreetly, and effectively. With consummate skill and energy they gathered the reins of Government in their own hands.” And threw all the men out. The new Constitution, the Preceptress tells Vera, “provided for the exclusion of the male sex from all affairs and privileges for a period of one hundred years. At the end of that time not a representative of the sex was in existence.” Italics courtesy of the Preceptress. The men aren’t killed off. Instead, when they can no longer run things, spend their time and energy wheeling and dealing and being important, they simply wither away!

With them out of the picture, Mizoran society soars toward perfection.

And the key to it all, indeed, the key to the novel’s purpose, is female education.

Prior to their takeover of Mizora’s government, “colleges and all avenues to higher intellectual development had been rigorously closed against them. The professional pursuits of life were denied them”—just as they were in the United States at the time.

Women in 1880 were largely still supposed to be only mothers and homemakers. But things were changing in small ways. One effect all those new factories popping up had, for better or worse, was to give women jobs working in them, taking them out of the home in previously unthought-of numbers. Emancipation of former slaves by constitutional amendment added impetus for women’s suffrage as well, and such leaders as Elizabeth Cady Stanton (who had organized the first women’s rights convention in 1848), and Susan B. Anthony had started the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869 and repeatedly petitioned Congress to give women the vote. Higher education was still primarily male. Oberlin College had been one of the first to admit women in the 1830s. The first all-women’s college opened in 1836 as Georgia Female College (now Wesleyan College), and Mount Holyoke had begun as a female seminary in 1837. Vassar didn’t come along until 1861, Hunter College in 1870, and Smith and Wellesley in 1875, making them brand-new institutions when Lane was writing. But most women were stuck at home, doing housework and raising kids, stuck, too, up on that pedestal, where sentimental worship, far from elevating them, kept them from acting on any professional aspirations they might entertain. Educated, accomplished women were in the main regarded as “unnatural.” Anything beyond a little schoolmarming was suspect, and that was regarded as the province of unfortunate spinsters unable to perform women’s “true calling”—childbearing and housekeeping. The pressures to restrict women to their “special province”—the home—were still tremendous in 1880.

Lane envisioned a life for women with none of these restrictions.

Vera is ensconced in the National College to learn their musical language and soon finds that universal education is of the highest importance to the Mizorans—and that teachers are not only the highest-paid profession of all, they represent the pinnacle of Mizora’s intellectual aristocracy. Dream on, Mary Bradley. “The idea of a Government assuming the responsibility of education, like a parent securing the interest of its children, was all so new to me,” Vera thinks, “and yet, I confessed to myself, the system might prove beneficial to other countries than Mizora.” She reflects that in her world, “education was the privilege only of the rich. And in no country, however enlightened, was there a system of education that would reach all.”

The rest of the novel details the fabulous rewards of Mizora’s education policy.

One has been to provide a terrific standard of living for all. The Preceptress admonishes Vera regarding the potential benefits of universal education for her world: “The bright and eager intellects of poverty will turn to Chemistry to solve the problems of cheap Light, cheap Fuel and cheap Food. When you can clothe yourselves from the fibre of the trees, and warm and light your dwellings from the water of your rivers.” They’ve figured out how to create cheap energy by reducing water to its two separate elements by zapping it with electricity, then burning the result. “Eat of the stones of the earth, Poverty and Disease will be as unknown to your people as it is to mine.”

Better living through chemistry.

Lane does come up with a number of nifty sci-fi devices. The preferred conveyance is a low carriage “propelled by compressed air or electricity.” They also have airplanes—this nearly twenty-five years before successful heavier-than-air flight, though many at the time were working on it. More predictive is the Mizorans’ “elastic glass” (plastic by any other name) “as pliable as rubber.” Almost indestructible, among its many uses, “all cooking utensils were made of it” and “all underground pipes were made of it.” It’s also spun into “the frailest lace,” which “had the advantage of never soiling, never tearing, and never wearing out,” sort of a precursor of that old Alec Guinness movie, The Man in the White Suit. Other gizmos anticipate television, e-mail, and holography. The key to most of these advances is electricity, and naturally all of the living spaces and city streets in Mizora are bathed in bright artificial lighting. This was more a sign of the times than some visionary stroke, since even as Lane was writing, tireless Thomas Alva Edison was slaving away in his lab looking for the perfect filament for his revolutionary incandescent lightbulb, and in 1879 the first electric streetlights in the United States were turned on around Public Square in Cleveland, Ohio.

Such gadgets are a commonplace in the futuristic hollow earth novels from this time. What sets Mizora apart is its vision of an ultimate matriarchy, where women have done away with men entirely. Here mothers produce only daughters and live with them in harmony until the daughters in turn become mothers. Lane is vague about how this asexual procreation is achieved. She says they have discovered “the secret of life” and suggests something like in vitro conception.

Like the narrator of The Coming Race, Vera at last decides to go back home with her friend Wauna, the Preceptress’s daughter, to show her world a shining example of Mizoran society and to proselytize for universal free education. But it doesn’t work. Vera finds that her husband and son, who had migrated to the United States, are both dead. The brutality of the surface world overwhelms Wauna, and she dies attempting to return to Mizora. Nearly her last words are: “The Great Mother of us all will soon receive me in her bosom. And oh! my friend, promise me that her dust shall cover me from the sight of men.” True to her school to the very end.

In 1882, just a year after Lane’s story was serialized, a novel titled

Pantaletta appeared. It described a comic dystopia written with broad-stroke vaudeville flourishes that reads like a send-up of the serious feminism in

Mizora. The author was Mrs. J. Wood, likely the pseudonym of a man unappreciative of efforts toward women’s rights.

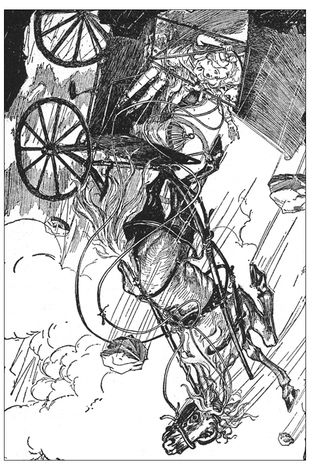

58The narrator is an American named Icarus Byron Gullible. After demolishing the family fortune starting a newspaper but fortuitously marrying a wealthy young woman, he devotes his time after serving in the Civil War to invention, and the result is an aircraft he calls the American Eagle.

Gullible’s goal? The North Pole. He wants to get there “to stop the further sacrifice of heroic lives by polar expeditions.” With success he plans to “patent my invention and organize a company” to manufacture his Eagle airships, these to “carry all kinds of passengers to the new American possessions, at remunerative rates.” His Eagle flies, but not very fast, so the trip to the pole takes days. He passes “leagues of glistening ice” and then “below me, apparently boundless in diameter, rolled the gulf of gulfs,” a combination of the open polar sea and the great polar abyss. He flies on, the temperature rises, he sights land unknown on maps, and comes to earth at last, of course, in some Edenic country—“a spot which rivalled the garden of our first parents in beauty.” He is immediately nabbed by a group of martial women wearing strange garb and taken prisoner. His chief captor is the Pantaletta of the title, a half-mad virago given to loony, disjointed Lady Macbeth soliloquies who’s also captain of the army. Gullible is drugged and dragged off to meet the president of the Republic of Petticotia, a topsy-turvy land where women have assumed power as well as men’s clothing, while the remaining men (millions have fled) are forced to wear what were formerly women’s clothes and perform all the duties formerly relegated to women. Petticotia is a cross-dresser’s paradise, where transvestitism has the rule of law. The word “man” has been banned as well. Former “men” are now called “heshes,” while women are “shehes.” The absurdity of this is a clear indication of the writer’s attitude toward women’s equality.

The novel ends with Gullible popping up out of the interior world at the North Pole and winging his way south toward Greenland, eager to report that “the North Pole is discovered and is ours.” Filled with emotion, he rhapsodizes, “Oh, my native land, my soul goes out to thee . . . Long seems the time since I stretched me under thy umbrageous trees and felt the gentle influence of thy emerald face.”

After

The Coming Race, Mizora, and

Pantaletta, novels of the 1880s and 1890s set in the hollow earth both multiplied and took on a certain sameness. It would be tedious to consider every one in detail. Indeed, it would be impossible, since several of them, while continuing to exist on various bibliographical lists, have proved impossible to turn up despite considerable searching. But the number of hollow earth novels produced between 1880 and 1915 is remarkable. The list includes:

Mizora by Mary Bradley Lane (1880).

Pantaletta: A Romance of Sheheland by Mrs. J. Wood (1882).

Interior World, A Romance Illustrating a New Hypothesis of Terrestrial Organization &c by Washington L. Tower (1885).

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder by Anonymous [James DeMille] (1888).

Under the Auroras, A Marvelous Tale of the Interior World by Anonymous [William Jenkins Shaw] (1888).

Al-Modad; or Life Scenes Beyond the Polar Circumlfex. A Religio-Scientific Solution of the Problems of Present and Future Life by Anonymous [M. Louise Moore and M. Beauchamp] (1892).

The Goddess of Atvatabar by William R. Bradshaw (1892).

Baron Trump’s Marvellous Underground Journey by Ingersoll Lockwood (1893).

Swallowed by an Earthquake by Edward Douglas Fawcett (1894).

The Land of the Changing Sun by Will N. Harben (1894).

From Earth’s Center, A Polar Gateway Message by S. Byron Welcome (1894).

Forty Years with the Damned; or, Life Inside the Earth by Charlies Aikin (1895).

The Third World, A Tale of Love & Strange Adventure by Henry Clay Fairman (1895).

Etidorhpa by John Uri Lloyd (1895).

Through the Earth by Clement Fezandie (1898).

Under Pike’s Peak; or Mahalma, Child of the Fire Father by Charles McKesson (1898).

The Sovereign Guide: A Tale of Eden by William Amos Miller (1898).

The Last Lemurian: A Westralian Romance by G. Firth Scott (1898).

Through the Earth; or, Jack Nelson’s Invention by Fred Thorpe (1898).

The Secret of the Earth by Charles W. Beale (1899).

Nequa; or, The Problem of the Ages by Jack Adams [pseud. of Alcanoan O. Grigsby and Mary P. Lowe] (1900).

Thyra, A Romance of the Polar Pit by Robert Ames Bennet (1901). Intermere by William Alexander Taylor (1901-1902)

The Land of the Central Sun by Park Winthrop (1902).

The Daughter of the Dawn by William Reginald Hodder (1903).

My Bride from Another World: A Weird Romance Recounting Many

Strange Adventures in an Unknown World by Rev. E. C. Atkins (1904).

Mr. Oseba’s Last Discovery by George W. Bell (1904).

Under the World by John DeMorgan (1906).

The Land of Nison by C. Regnus [pseud. of Charles Sanger] (1906).

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz by L. Frank Baum (1908).

The Smoky God by Willis George Emerson (1908).

Five Thousand Miles Underground, or The Mystery of the Centre of the Earth by Roy Rockwood [pseud. of Howard Garis] (1908).

Upsidonia by Archibald Marshall (1915).

Published anonymously in 1888, A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder is an example of a creeping sameness in hollow earth novels of the time. Various amounts of Symmes, Poe, and Verne are stirred together to concoct warmed-over hollow earth stew, including the requisite sea monster shown here on the cover of a pirated British edition.

Let’s look at a small sample of the titles.

The opening sections of

A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, published anonymously in 1888, exemplify the creeping sameness. Various amounts of Symmes, Poe, and Verne are stirred together to concoct a warmed-over hollow earth stew. Adam More (Adam Seaborn was Symmes’ hero, you will remember; and More wrote the first

Utopia), shipwrecked with a companion in the Southern Ocean, lands on an island peopled by ferocious black cannibals who promptly eat his pal. More escapes on a small boat, drawn ever southward by a strong current until his craft is sucked downward into a black tunnel and pops up in a calm, warm sea lapping against a paradisiacal countryside. Here the author reaches even farther back in his ransacking, giving us a turned-on-its-head society that seems inspired by those in

Niels Klim. As Steve Trussel summarizes the action,

Upon landing, he finds a strange race very much resembling Arabs. They take him to their underground city, where he is taught a language similar to Arabic by the beautiful Almah, and discovers that the cultural and moral values of this peculiar race are weirdly inverted. These pseudo-Arabs see better in the dark than in daylight. They seek poverty, giving their possessions to whomever will take them; they long for death as the highest blessing of their lives; and, although peaceful, they practice human sacrifice on hundreds of willing victims. Adam and Almah fall in love, and find that they are destined to be given the honor of dying for her people. At the last moment, More kills several of the populace with his rifle, and the multitudes, awe-stricken, fall down and worship him as a god who can bring the greatest good—death—instantly.

59This novel is at best an orientally embroidered celebration of life over death, an exotic romance without much redeeming value. Perhaps most interesting is that this story appeared serially in nineteen installments in one of the most popular American magazines of the time—Harper’s Weekly (which billed itself as “A Journal of Civilization”)—an indicator of how mainstream the idea of the hollow earth had become. The anonymous author turned out to be a Canadian college professor named James de Mille (1833–1880), a prolific and popular novelist in his day. He’s pretty much forgotten now, though he lives on in Ph.D. dissertations and academic criticism, and a surprising number of his novels are available online as e-texts. A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder, published posthumously, is considered the first Canadian science fiction novel and was reprinted by Insomniac Press in 2001.

William R. Bradshaw (1851–1927) wrote The Goddess of Atvatabar, first published in 1892. This hollow earth novel has an almost overwhelming sumptuousness and richness of detail. An Irish immigrant who settled in Flushing, New York, Bradshaw was a regular contributor to magazines, edited Literary Life and Decorator and Furnisher, and was associated with Field and Stream as well. At his death in 1927 he was a Republican district captain in Flushing and president of the New York Anti-Vivisection Society.

A number of new elements show themselves here. One is revealed in the full title:

THE

GODDESS OF ATVATABAR

BEING THE

HISTORY OF THE DISCOVERY

OF THE

INTERIOR WORLD

AND

CONQUEST OF ATVATABAR

Earlier hollow earth novels such as Symzonia had land-grabbing imperialism as a subtext, but here it is announced blazing right in the title. This novel came at a time when America was running out of open land and the easy promise (seldom realized) of riches on the frontier. What had been called Seward’s Folly—the vast tract of Alaska purchased from Russia in 1867—was looking visionary by the end of the century. And 1892 was just a few years before American policy changed to engage in a little empire building in the form of the Spanish-American War, which on slim excuse not only kicked Spain out of the New World but occupied the Philippines as well. So the conquest of Atvatabar is imaginatively predictive of geopolitical forces starting to simmer in the real world.

And wouldn’t you know it? The name of the narrator/hero/chief conqueror is Commander Lexington White. The story opens aboard the Polar King, with White and his crew on a mission to discover the North Pole—something very much in the news at the time. Even as Bradshaw was writing, Admiral Robert Peary was making his second expedition to Greenland, a prelude to the one that would take him successfully to the pole on April 6, 1909—or so he believed and claimed. Toward the end of the nineteenth century and in the early years of the twentieth, the idea of reaching the pole became a sort of frenzy, with explorer after explorer obsessed with gaining the dubious “glory” of being the first to do so. Just as Poe had tried to cash in on a polar mania fifty years earlier, Bradshaw’s polar framing for his hollow earth novel was quite timely.

On the Polar King, frustrated at trying to find an opening in the ring of polar ice, they fire one of their powerful guns containing shells of “terrorite” at it—a supergunpowder of White’s invention—cleaving the mountain of ice and creating a narrow passage to, yes, the open polar sea lying beyond. As they sail into it, White reflects, “I was romantic, idealistic. I loved the marvelous, the magnificent, and the mysterious . . . I wished to discover all that was weird and wonderful on the earth.” And does his wish ever come true.

White says he became absorbed in this polar quest after learning about the failure of a recent expedition whose ship was frozen in at Smith’s Sound in Baffin Bay, but had tried for the pole in a “monster balloon,” failing when the balloon’s car smashed into an iceberg. This reminded him of “the ill-fated Sir John Franklin and

Jeannette expeditions,” which in turn led him to read “almost every narrative of polar discovery” and to converse “with Arctic navigators both in England and the United States.” His polar homework fits neatly into a tradition of hollow earth novels going back to Symmes and Poe. He says he found it strange that modern sailors “could only get three degrees nearer the pole than Henry Hudson did nearly three hundred years ago,” and when his father opportunely dies and leaves him a huge fortune, he decides to try for the pole. He builds the

Polar King according to his own advanced specs, one being a handy device also of his own invention, an “apparatus that both heated the ship and condensed the sea water for consumption on board ship and for feeding the boilers.” As he’s listing the other provisioning details, the first hint of the novel’s deep eccentricity appears. Along with “the usual Arctic outfit to withstand the terrible climate of high latitudes,” White has a special item of clothing made for all:

Believing in the absolute certainty of discovering the pole and our consequent fame, I had included in the ship’s stores a special triumphal outfit for both officers and sailors. This consisted of a Viking helmet of polished brass surmounted by the figure of a silver-plated polar bear, to be worn by both officers and sailors. Each officer and sailor was armed with a cutlass having the figure of a polar bear in silver-plated brass surmounting the hilt.

White sets out with his ace crew, not via Greenland and Baffin Bay as so many had before him, but through the Bering Straits, despite the

Jeannette expedition’s horrific experiences while attempting the same route.

60 They encounter the open polar sea and the usual abundance of wildlife up there, and at last Professor Starbottle, the chief scientist aboard, proclaims, “I am afraid, Commander, we will never reach the pole . . . we are falling into the interior of the earth!” After predictable shouts of “Turn back the ship!” the pilot observes that they are still sailing along nicely. “If the earth is a hollow shell having a subterranean ocean, we can sail thereon bottom upward and masts downward, just as easily as we sail on the surface of the ocean here.” Here, as in other hollow earth novels, ideas of gravity are conveniently cockeyed. They press on into the polar opening. “The prow of the

Polar King was pointed directly toward the darkness before us, toward the centre of the earth.” A dozen of the more fearful sailors are permitted to take a boat and head back where they came from.

About 250 miles down into the abyss they begin to experience lessened gravity, while getting their first glimpse of “an orb of rosy flame”—Swang, the inner earth sun. Professor Starbottle exclaims, surveying the scene with his telescope, “The whole interior planet is covered with continents and oceans just like the outer sphere!”

“‘We have discovered El Dorado,’ said the Captain.”

“‘The heaviest elements fall to the centre of all spheres,’ said Professor Goldrock. ‘I am certain we shall discover mountains of gold ere we return.’” Ideas of profit never lag far behind the excitement of discovery.

A storm comes up after a week’s subterranean sailing, providing the first real taste of the sensuous detail to come:

The sun grew dark and appeared like a disc of sombre gold. The ocean was lashed by a furious hurricane into incredible mountains of water. Every crest of the waves seemed a mass of yellow flame. The internal heavens were rent open with gulfs of sulphur-colored fire . . . a golden-yellow phosphorescence covered the ocean. The water boiled in maddening eddies of lemon-colored seas, while from the hurricane decks streamed cataracts of saffron fire. The lightning, like streaks of molten gold, hurled its burning darts into the sea. Everything bore the glow of amber-colored fire.

There is a sumptuous, painterly quality to the writing throughout the book. This is a hollow earth paradise of exquisite detail described in exquisite detail, literally reveling in it, though after a while it almost becomes overwhelming, like one too many bites of a thirteen-layer German chocolate cake. This hyperestheti-cism is part of Atvatabar’s larger purpose—to show a society as devoted to art and spirituality as most are to profit and power. It’s as if Bradshaw is straining to take the visual ideas and aesthetics of newly developing art nouveau—a style that had just come along in the 1880s, breaking with classicism, emphasizing rich organic qualities—and render them in prose. One goal of art nouveau (which had its origins in the 1860s with William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement) was to integrate beauty into everyday life, to make people’s lives better by greater exposure to it, and this is a main pillar of the civilization White & Co. encounter—before they begin crashing around in it ruining everything, anyway.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s son, Julian, wrote the introduction to

The Goddess of Atvatabar, in which he raves about the novel as a fine example of portraying the “ideal” in fiction, taking the opportunity to beat such “realists” as Zola and Tolstoy about the head and shoulders and claiming that their day has come and gone—a singularly wrongheaded judgment that served his own writerly purposes. Like Bradshaw’s novel, Julian Hawthorne’s fiction chiefly dealt with the fantastic and the supernatural. After citing Symmes, Verne, and Bulwer-Lytton’s

The Coming Race—proof he’s done his hollow earth homework—Hawthorne declares that Bradshaw “has not fallen below the highest standard that has been erected by previous writers,” and in fact “has achieved a work of art which may rightfully be termed great.” It’s actually superior to Verne, who, “in composing a similar story, would stop short with a description of mere physical adventure.” Bradshaw goes beyond this, creating “in conjunction therewith an interior world of the soul, illuminated with the still more dazzling sun of ideal love in all its passion and beauty.” This world of the soul lies at

Atvatabar’s core:

The religion of the new race is based upon the worship of the human soul, whose powers have been developed to a height unthought of by our section of mankind, although on lines the commencement of which are already within our view. The magical achievements of theosophy and occultism, as well as the ultimate achievements of orthodox science, are revealed in their most amazing manifestations, and with a sobriety and minuteness of treatment that fully satisfies what may be called the transcendental reader.

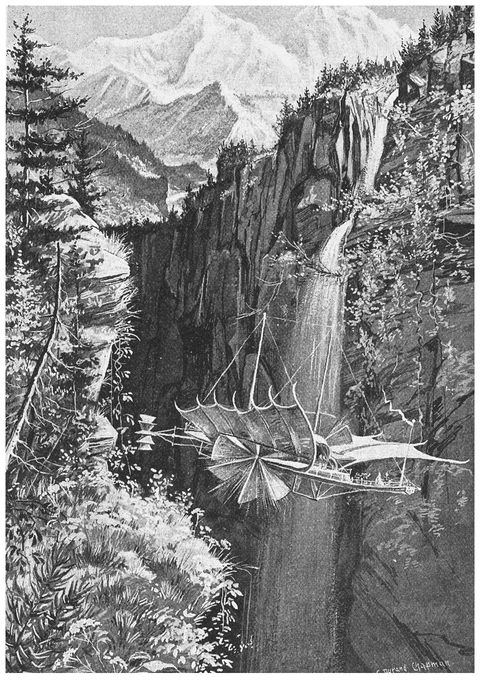

While it strives for a certain high-mindedness, The Goddess of Atvatabar is shot through with elements of Gilbert and Sullivan–style comic opera. The Polar King’s first encounter with the people down here comes when the crew sees several flying soldiers, hovering above the ship like large bumblebees, wearing strange uniforms and flapping mechanical wings. Flathootley, the resident buffoon, makes a leap at one, who flits out of the way, leaving Flathootley to plop into the ocean, from which he is rescued by one of the flying soldiers, who deposits him back on deck—and is promptly captured as a reward for his kindness. Examining the captive’s wings, they discover that a small “dynamo” powers them, consisting “of a central wheel made to revolve by the attraction of a vast occult force evolved from the contact of two metals . . . a colossal current of mysterious magnetism made the wheel revolve.” Here again electromagnetism appears as the occult force that propels all sorts of ingenious gadgets down here in Plutusia, as the realm is known.

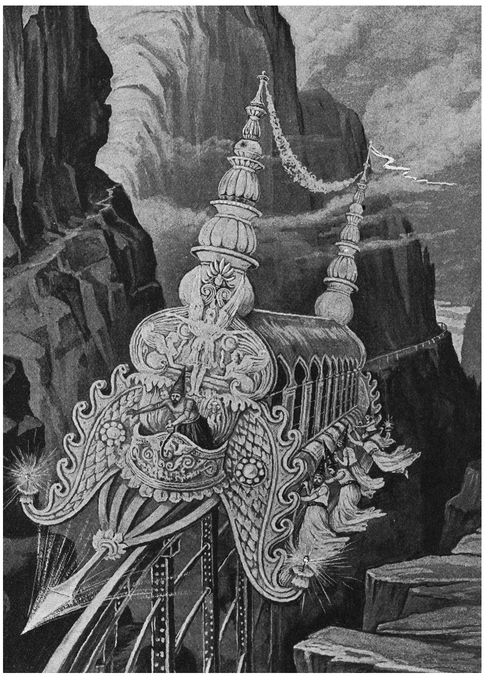

Lyone, the goddess of Atvatabar, in all her over-the-top splendor.

They learn Atvatabarese from the two flying soldiers, who direct the

Polar King to Atvatabar’s principal port and fill them in on the basics of the geography and social structure. The layout of the interior world is analogous to the known surface world—its map is reproduced here on page 186. The government is an elective monarchy, with a king and nobles elected for life. “The largest building in Calnogor was the Bormidophia, or pantheon, where the worship of the gods was held. The only living object of worship was the Lady Lyone, the Supreme Goddess of Atvatabar. There were different kinds of golden gods worshipped, or symbols that represented the inventive forces, art, and spiritual power.” The summary continues: “The Atvatabarese were very wealthy, gold being as common as iron in the outer world.” As always, luxury beyond imagination is the rule down here. Things are really up-to-date in Atvatabar:

There were plenty of newspapers, and the most wonderful inventions had been in use for ages. Railroads, pneumatic tubes, telegraphs, telephones, phonographs, electric lights, rain makers, seaboots, marine railroads, flying machines, megaphones, velocipedes without wheels, aërophers, etc., were quite common, not to speak of such inventions as sowing, reaping, sewing, bootblacking and knitting machines. Of course printing, weaving, and such like machines had been in use since the dawn of history. Strange to say they had no steam engines, and terrorite and gunpowder were unknown. Their great source of power was magnicity, generated by the two powerful metals terrelium and aquelium, and compressed air their explosive force.

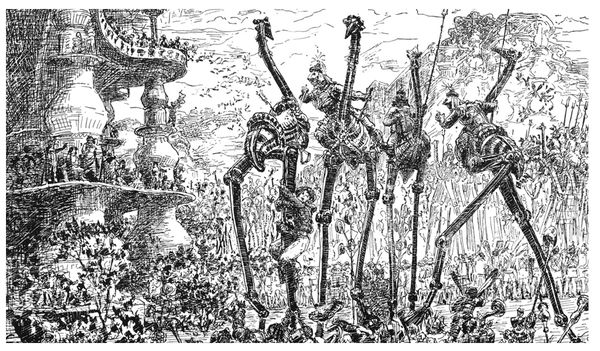

The bockhockids, shown here towering above the crowd, are “immense walking machines” reminiscent of ostriches. These are the ungainly mounts of the Atvatabarese cavalry and police force.

The lillipoutum, shown here, “was another wonderful creature, half-plant, half-bird.”

“They were a peaceful people, and Atvatabar being itself an immense island continent, lying far from any other land, there had been no wars with any external nation, nor even civil war, for over a hundred years.” As soon as virile Commander White lays eyes on Lyone, not only fetching but a goddess to boot, Atvatabar’s comfortable tranquillity is doomed.

The Polar King pulls up to the wharf—constructed of white marble—to a huge festive greeting by the governor and welcoming throngs that include regiments of cavalry mounted on mechanical ostriches. “They were forty feet in height from toe to head . . . The iron muscles of legs and body, moved by a powerful magnic motor inside the body of the monster, acted on bones of hollow steel.” As the sailors scurry up the legs to mount them, “a military band composed of fifty musicians, each mounted on a bockhockid, played the March of Atvatabar in soul-stirring strains . . . A brigade of five thousand bockhockids fell into line as an escort of honor,” and it’s off in procession through the beautiful all-marble city. These ungainly, not to say wildly unlikely, bockhockids would suggest this is satire, but given all the other oddball stuff in the book, I’d have to say it’s not. Rather it seems to be evidence that Bradshaw was letting his imagination sprout any strange fruit it might—and may have had a little help from his chemical friends as well. There’s a distinctly druggy cast to the whole business. Another such example from a little farther on is a little botanical garden containing specimens merging the plant and animal kingdoms, flowers blooming kitten heads, flitting birds trailing aerial roots. A spoof on Darwin? Or just trippy flashes? My vote goes to the latter. There’s a hypersensuous quality, a reveling in minute physical detail and description practically for its own sake—along with these stoner ideas—that suggests Bradshaw may have been indulging in some writer’s little helpers.

Boarding the Sacred Locomotive, after appropriate preparatory prayers (“Glorious annihilator of time and space, lord of distance, imperial courier”), White and a few officers are whisked five hundred miles inland to Calnogor for a reception with the king and queen. Between heady glasses of squang, the king explains Atvatabar’s religion to White. “We worship the human soul,” he says, “under a thousand forms, arranged in three great circles of deities.” These are the gods of invention, the gods of art, and a third group containing “the spiritual gods of sorcery, magic and love.” Together “this universal human soul forms the one supreme god Harikar, whom we worship in the person of a living woman, the Supreme Goddess Lyone.”

(above) Lyone’s Aerial Yacht (left) and The Sacred Locomotive (right). Note too Atvatabar’s dramatic, picturesque landscape.

The king drones on, detailing the various religious divisions. After the obligatory tour of religious temples, they’re taken to meet the living goddess Lyone, who is lovely, with bright blue hair and “firm and splendid” breasts. “I was entranced with the appearance of the divine girl . . . All at once she gazed at me! I felt filled with a fever of delicious delight, of intoxicating adoration.”

“Our religion is a state of ecstatic joy,” Lyone says, “chiefly found in the cultured friendship of counterpart souls, who form complete circles with each other.” They are known as “twin-souls,” and there are twenty thousand in Egyplosis, where Lyone and these devotees live.

When Lyone is called to Egyplosis to oversee the installation of a twin-soul, White is invited to go along on her aerial yacht, another ornate contraption powered by magnicity. This seat of worship is a city consisting of a great temple carved from a single block of pale green marble, with “one hundred subterranean temples and labyrinths” beneath it, having “the enchanted charm of Hindoo and Greek architecture, together with the thrilling ecstasy of Gothic shrines.” Bradshaw can’t resist voluptuous descriptions that amount to aesthetic heavy breathing:

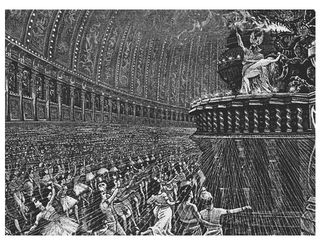

The chief temple at Egyplosis was interiorly of semi-circular shape, like a Greek theatre, five hundred feet in width. It was covered like the pantheon with a sculptured roof and dome of many-colored glass. The roof was one hundred and thirty feet above the lowest tier of seats beneath. The walls were laboriously sculptured dado and field and frieze, with bas-reliefs of the same character as the golden throne of the gods that stood at the centre of the semi-circle.

The Living Battery consists of hundreds of twin-souls.

The dado was thirty-two feet in height, on which were carved the emblems of every possible machine, implement or invention that conferred supremacy over nature in idealized grandeur. Battles of flying wayleals [soldiers] and races of bockhockids were carved in great confusion. It was a splendid reunion of science and art...

Above all rose the dome whose lights were fadeless. The pavement of the temple had been chiselled in the form of a longitudinal hollow basin, containing a series of wide terraces of polished stone, whereon were placed divans of the richest upholstery. In each divan sat a winged twin-soul, priest and priestess, the devotees of hopeless love. On the throne itself sat Lyone, the supreme goddess, in the semi-nude splendor of the pantheon, arranged with tiara and jewelled belt and flowing skirt of sea-green aquelium lace. She made a picture divinely entrancing and noble. Supporting the throne was an immense pedestal of polished marble, fully one hundred feet in diameter and twenty feet in height, which stood upon a wide and elevated pavement of solid silver, whereon the priests and priestesses officiated in the services to the goddess. On crimson couches sat their majesties the king and queen of Atvatabar, together with the great officers of the realm. Next to the royal group myself and the officers and seamen of the Polar King occupied seats of honor. Behind, around and above us, filling the immense temple, rose the concave mass of twin-souls numbering ten thousand individuals, each seated with a counterpart soul. The garments of both priests and priestesses were fashioned in a style somewhat resembling the decorative dresses seen on Greek and Japanese vases, yet wholly original in design. In many cases the priestesses were swathed in transparent tissues that revealed figures like pale olive gold within.

Stop him before he describes more!

Afterward, in a private audience, Lyone and White at last get down to it. “The pleasure we aspire to is superior to any physical delight,” she insists. “It is the quintessence of existence. We are willing to pay the price of hopelessness to taste such nectar.” She explains that at one time in its past, Atvatabar experimented with a form of free love, but the result was disastrous: “unbridled license devastated the country.” So the lawmakers reestablished marriage as “the only law suitable to mankind.” But some of these married couples chose to remain celibate, and “for these Egyplosis was founded, for the study and practice of what is really a higher development of human nature and in itself an unquestionable good.” This higher state of celibacy, of course, echoes the practices of many nineteenth-century utopian communities, from the Rappites to the Koreshans.

But White isn’t convinced. “Hopeless love seems to me one of the most disquieting things in life. Its victims, happy and unhappy, resisting passion with regret or yielding with remorse, are ever on the rack of torture.” Is everyone content with their celibate state here? he asks. Just then they hear a terrible commotion, shouts, a woman shrieking. Two twin-souls are brought before Lyone, and the woman of the pair is carrying a beautiful baby. Apparently not everyone. “Did you not think of your lifelong vows of celibacy?” asks Lyone. “We have,” says the youth. “Such vows are a violation of nature. Everything here bids us love, but the artificial system under which we have lived arbitrarily draws a line and says, thus far and no further. Your system may suit disembodied spirits, if such exist, but not beings of flesh and blood. It is an outrage on nature. We desire to leave Egyplosis.” And furthermore, he says, “There are thousands of twin-souls ready to cast off this yoke. They only await a leader to break out in open revolt.”

The next day Lyone makes a confession to White. She came to Egyplosis a true believer in ideal love and found it in a chaste, loving connection with a twin-soul. But then he died. Heartbroken, she was elevated to the throne of goddess, but “I continually long for something sweeter yet . . . at times I know I could forgo even the throne of the gods itself for the pure and intimate love of a counterpart soul.” What would be the punishment for this? White asks. “A shameful death by magnicity. No goddess can seek a lover and live.” And yet, moments later, White can control himself no longer:

I sprang forward with a cry of joy, falling at the feet of the goddess. I encircled her figure with my arms and held up my face to hers. Her kiss was a blinding whirlwind of flame and tears! Its silence was irresistible entreaty. It dissolved all other interests like fire melting stubborn steel. It was proclamation of war upon Atvatabar! It was the destruction of a unique civilization with all its appurtenances of hopeless love. It was love defying death. Thenceforward we became a new and formidable twin-soul!

But before they actually declare war, Lyone takes White below to the Infernal Palace to meet the Grand Sorcerer. Twenty thousand twin-souls appear, all carrying wands connected to “fine wires of terrelium.” They commence a “strange dance” beneath a huge statue of a golden dragon, and “a shower of blazing jewels issued from its mouth. There were emeralds, diamonds, sapphires, and rubies flung upon the pavement.” To impress White and amuse Lyone, the sorcerer sets these hard-dancing ecstatic souls to creating an entire island, whose existence can only be maintained “so long as the twin-souls support it by never-ceasing ecstasy.” During this idyll their love grows, but on their return they find they’ve been spied on. But rather than give up White and send him packing back to the surface, Lyone tells the king that she’s seen the light. The whole system they’ve been living by is wrong and rotten. “The true union of souls is not artificial restraint.” When Lyone renounces her throne and calls for religious reform, the king proclaims that the penalty for this is “death on the magnetic scaffold.” White is ordered out of Atvatabar. Not a chance. This means war!

Of the population of 50 million, 20 million are for Lyone and reform. Soon civil war rages, with casualties on both sides. Just as White’s forces are losing a sea battle, two fighting ships under the flags of the United States and England show up and save the rebels. After a torturous trek through arctic wastes, those fearful sailors who left the ship had spread the word about the existence of the interior world. Bradshaw reproduces a headline from a New York newspaper:

AN ASTOUNDING DISCOVERY!

The North Pole Found To Be An Enormous Cavern,

Leading To A Subterranean World!

The Earth Proves To Be A Hollow Shell One Thou-

Sand Miles In Thickness, Lit By An Interior Sun!

Oceans And Continents, Islands And Cities Spread Upon

The Roof Of The Interior Sphere!

Tremendous Possibilities For Science And Commerce!

The Fabled Realms Of Pluto No Longer A Myth

Gold! Gold! Beyond The Dreams Of Madness!

The American and British ships that steam into view and save the day for White’s forces are the first of many rushing to check out the interior world and claim a piece of the pie: “All civilized nations immediately fitted out vessels of discovery . . . for the benefit of their respective governments.” The blithe imperialism in all of this couldn’t be more blatant. The assumption is that Atvatabar is there to be exploited, no matter what the inhabitants might have to say about it. And there’s a parallel attitude regarding its culture and religion. Lyone is ready to stop being a

goddess because she’s so attracted to White, and willing to let her country plunge into bloody civil war, the result of which is an utter wreckage of the value system that had been in place there for centuries. It’s all presented as reform. Six years after

Atvatabar was published, the United States marched into Cuba and the Philippines. Certainly the Spanish government in Cuba “had long been corrupt, tyrannical, and cruel,” but intervention in the long Cuban civil war had as much to do with economic considerations and a national spirit of empire building as with altruism.

61

John Uri Lloyd’s Etidorhpa, published in 1895, is easily the weirdest hollow earth novel of all. “To say that it is one of the strangest books of the century is to put it mildly,” wrote a contemporary reviewer in Lloyd’s hometown Cincinnati Enquirer. Another for the Chicago Medical Times gushed that “It excels Bulwer-Lytton’s Coming Race and Jules Verne’s most extreme fancy. It equals Dante in vividness and eccentricity of plot . . .” The Western Druggist, also published in Chicago, called it “a book like to nothing ever before seen; a book in which are blended, in a harmonious whole, romance, exact science, alchemy, poetry, esoterism, metaphysics, moral teachings and bold speculation.”

Lloyd’s novel was reviewed in these medical papers because he was a pharmacist who’d made a reputation writing on pharmacological subjects before the publication of Etidorhpa (Aphrodite spelled backwards). “Psychedelics Lloyd must have had contact with include marijuana and opium poppies,” wrote Neal Wilgus in the introduction to a 1976 reprint, “belladonna containing plants such as nightshade, henbane and jimsonweed . . . ergot, an LSD containing fungus . . . most likely of all perhaps are the Psilocybe mexicana and other psilocybin producing mushrooms of Mexico which act very much like LSD and mescaline in producing just the kind of ‘head trip’ which Lloyd calls Eternity without Time.” Lloyd appears to have been the Carlos Castaneda of the hollow earth. As a more recent reviewer put it, “Etidorhpa recounts one of the earliest and most intensely evoked hallucinatory journeys in literature.”

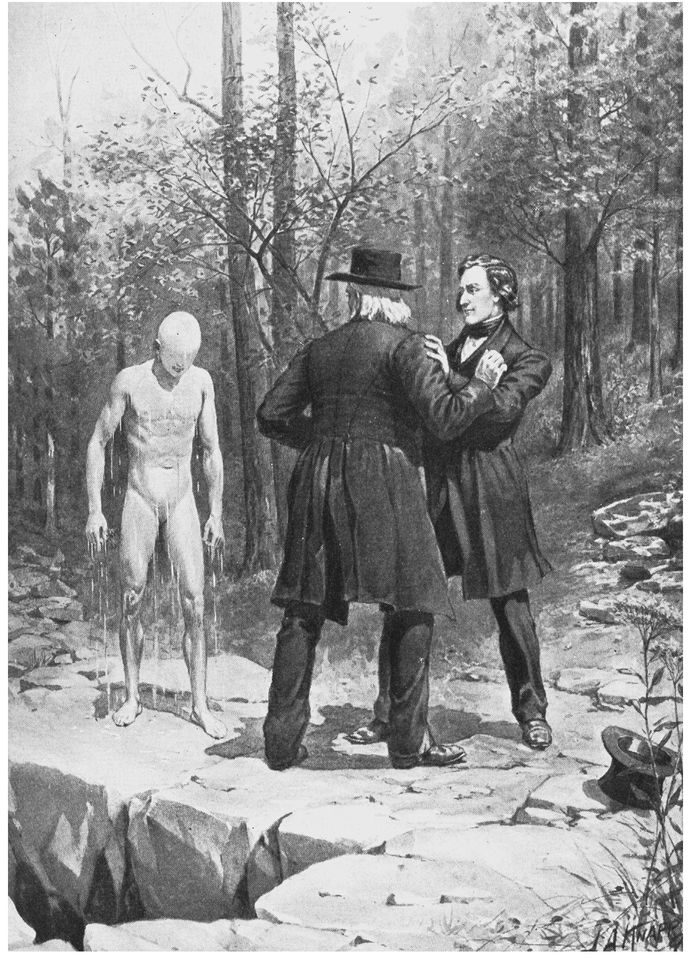

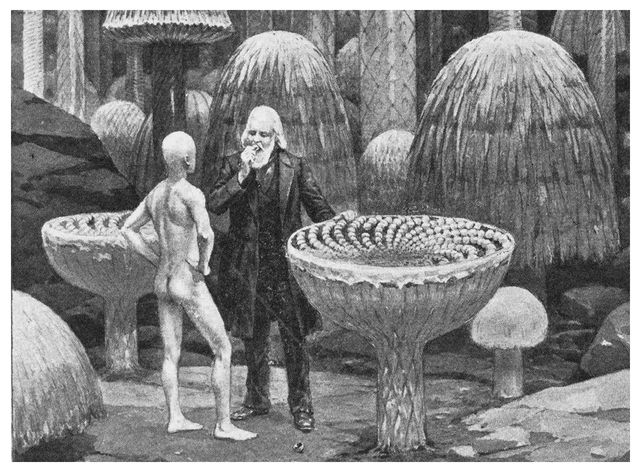

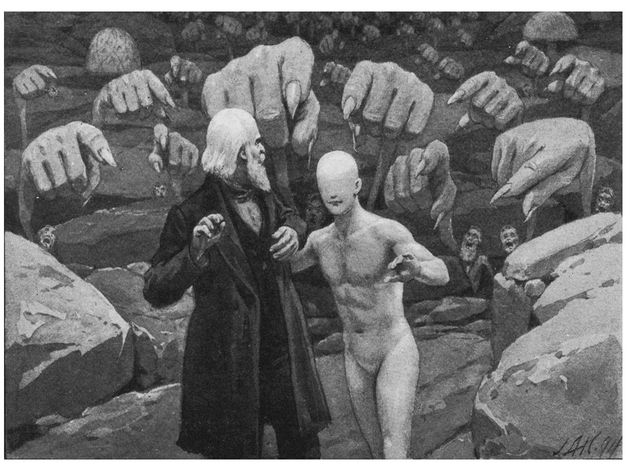

John Uri Lloyd’s Etidorhpa (1895) includes this eyeless humanoid creature that looks like a cross between E.T. and a cave fish.

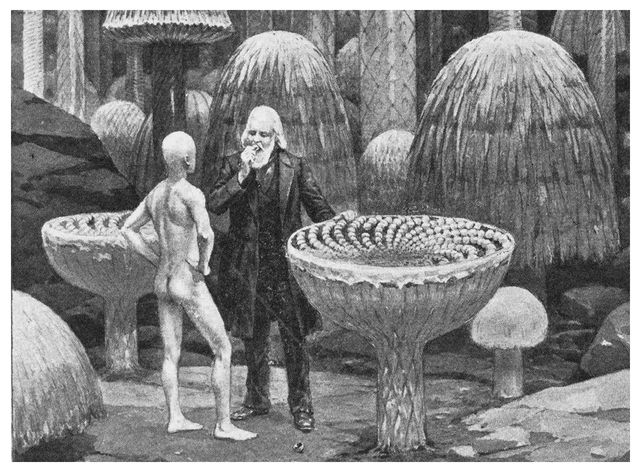

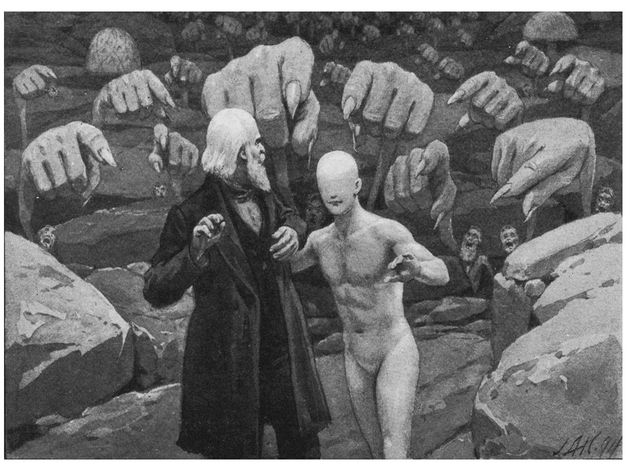

The narrator appears at Lloyd’s doorstep as an old bearded man and forces him to listen as he reads the manuscript he’s written. He has violated an occult society’s secret taboo, and his punishment is to be taken on a forced pilgrimage through a vast labyrinth leading down to the earth’s hollow center. He’s transported to a cave opening in Kentucky, where he is met by his guide—a gray-skinned eyeless humanoid creature who looks like a cross between E.T. and a cave fish. But the trip, while physical, is largely spiritual. He’s on his way to personal enlightenment and he is scared—suggestive of a line from Herman Hesse’s Demian: “Nothing in the world is more distasteful to a man than to take the path that leads to himself.”

Deep in the cavern, they pass through a forest of giant mushrooms and then zoom across a vast lake at nine hundred miles an hour in a metal boat with no seeming means of propulsion. The guide tries to explain that it taps an invisible “energy fluid,” but the narrator doesn’t understand. The lake is contained by a stone wall, beyond which looms “an unfathomable abyss.” Returning from this excursion, they continue downward. Gravity decreases to near zero, and his breathing slows until it stops; still he lives. The narrator is terrified and feels “an uncontrollable, inexpressible desire to flee.” His guide explains that breathing is just a “waste of energy,” that the closer you get to pure spirit it’s not needed. They’re in another mushroom forest. The guide breaks one open, and insists that he drink its “clear, green liquid.”

As the guide delivers a short history of drunkenness worldwide from the earliest times, they enter a cavern “resonant with voices—shrieks, yells, and maniacal cries commingled.”

“I stopped and recoiled, for at my very feet I beheld a huge, living human head. ‘What is this?’ I gasped. ‘The fate of a drunkard,’ my guide replied. ‘This was once an intelligent man, but now he has lost his body, and enslaved his soul, in the den of drink.’ Then the monster whispered, ‘Back, back, go thou back!’ . . . Now I perceived many such heads about us . . . I felt myself clutched by a powerful hand—a hand as large as that of a man fifty feet in height. I looked about expecting to see a gigantic being, but instead beheld a shrunken pygmy. The whole man seemed but a single hand. Then from about us, huge hands arose; on all sides they waved in the air. ‘Back, back, go thou back.’ . . . The amphitheater was fully a thousand feet in diameter, and the floor was literally alive with grotesque beings. Each abnormal part seemed to be created at the expense of the remainder of the body. Here a gigantic forehead rested on a shrunken face and body, and there a pair of enormous feet were walking, seemingly attached to the body of a child, and yet the face was that of a man.” “This is the Drunkard’s Den,” his guide tells him. “These men are lost to themselves and to the world. You must cross this floor. No other passage is known.” He adds, “Taste not their liquor by whatever form or creature presented.” If they offer inducements, he must refuse to drink or he’ll end up one of them.

(above) The subterranean pilgrim in Etidorhpa visits a mushroom forest (top); and tiny tormented people (bottom).

Abruptly he’s borne aloft by one of the huge hands and carried to a stone platform in the center of the cavern. Amid the grotesques, a handsome man appears to him, insisting he’s a friend, a deliverer, saying that all the deformities he’s seeing aren’t real, are produced in his imagination by the influence of an evil spirit (his guide), they’re really happy normal people. “They seek to save you from disaster. One hour of experience such as they enjoy is worth a hundred years of the pleasures known to you. After you have partaken of their exquisite joy, I will conduct you back to the earth’s surface whenever you desire to leave us.” Drink this! Tempted, the narrator begins to drink but then dashes the cup on a rock. Suddenly the twisted creatures and the handsome persuader vanish. Slowly they are replaced by beautiful vocal and instrumental music. And “by and by, from the corridors of the cavern, troops of bright female forms floated into view. Never before had I seen such loveliness in human mold.”

The following scene could have been choreographed by Busby Berkeley on acid.

Carrying “curious musical instruments and beautiful wands, they produced a scenic effect of rare beauty that the most extravagant dream of fairyland could not surpass. The great hall was clothed in brilliant colors. Flags and streamers fluttered in breezes that also moved the garments of the angelic throng about me.” They begin to dance around him to “music indescribable,” group after group of them, each singing “sweeter songs, more beautiful, and richer in dress than those preceding.” The narrator nearly swoons in ecstasy. “I was rapt, I became a thrill of joy. A single moment of existence such as I experienced, seemed worth an age of any other pleasure.”

Can he get any higher? Yes. The music ceases and Etidorhpa herself appears. “She stood before me, slender, lithe, symmetrical, radiant. Her face paled the beauty of all who preceded her.” She announces that “love rules the world, and I am the Soul of Love Supreme”—and that he can have her all to himself forever. She and her beautiful minions have appeared to him as a preview of things to come. But first he must undergo a few more trials. “You can not pass into the land of Etidorhpa until you have suffered as only the damned can suffer,” she says, offering him a cup filled with green liquid. Again, he almost drinks but dashes that cup to the floor too. Etidorhpa disappears along with all the chorus girls. The narrator finds himself back on the surface, surrounded by endless desert sand. For days he struggles along in the fiery heat, without food or drink. He’s dying of thirst when he encounters a caravan whose leader offers a lifesaving glass of clear green liquid. “No. I will not drink.” The caravan abruptly vanishes, and a cool, refreshing breeze begins to blow. Soon he is nearly freezing, and days pass without number. He curses God and prays for death. He wishes he’d given in to one of the tempters—but then, no. “I have faith in Etidorhpa, and were it to do over again I would not drink.”

The magic words! Suddenly he is once again back in the cavern with his guide. It’s all been a brief hallucination, occurring in the moment after he sipped the magic mushroom cocktail. Their journey continues, literally downhill for them and for the reader as well. They get to the end of a shelf of rock overhanging an unfathomable abyss—the enormous hollow center of the earth—and his guide bids the narrator to jump. Are you crazy? he asks. The guide says that here lies Enlightenment, grabs him, and they leap into nothingness. Instead of falling, they seem to float, and after a time they reach the very center, “the Sphere of Rest.” Here the narrator experiences a midair satori. “Perfect rest came over my troubled spirit. All thoughts of former times vanished. The cares of life faded; misery, distress, hatred, envy, jealousy, and unholy passions, were blotted from existence. I had reached the land of Etidorhpa—THE END OF THE EARTH.”

He’s achieved a moment of spiritual awakening. His guide tells him:

It has been my duty to crush, to overcome by successive lessons your obedience to your dogmatic, materialistic earth philosophy, and bring your mind to comprehend that life on earth’s surface is only a step towards a higher existence, which may, when selfishness is conquered, in a time to come, be gained by mortal man, and while he is in the flesh. The vicissitudes through which you have recently passed should be to you an impressive lesson, but the future holds for you a lesson far more important, the knowledge of spiritual, or mental evolution which men may yet approach; but that I would not presume to indicate now, even to you.

He stands on the edge of “The Unknown Country”—but cannot reveal what comes next. It would be too mind-blowing for mere mortals. And so ends the novel’s action.

Etidorhpa is horribly flawed as novels go—I’ve left out the frequent long tedious asides in which Lloyd challenges the writer of the manuscript about seemingly impossible aspects of his story, which he then explains/defends at “scientific” and philosophical length. But it is certainly a landmark departure from the usual hollow earth novels, using the conceit not for mere adventure, or as the device for concocting some new sociopolitical utopia. The utopia it presents, if it can be called that, is purely spiritual—however deeply weird.

Arguably the most boring hollow earth novel ever, in a couple of respects, is Clement Fezandie’s Through the Earth (1898). Fezandie (1865–1959) was a math teacher in New York City and eventually wrote science fiction for Hugo Gernsback (1884–1967), the pioneering editor who invented sci-fi magazines, starting with Amazing Stories in 1926. Through the Earth qualifies only marginally as a hollow earth novel. It tells of a project to bore a tunnel between New York City and Australia to carry goods and people between the two places, like the world’s longest freight elevator. Most of the book is occupied by an account of the first test ride, essayed by a brave impoverished lad for the prize money of £100 (offered because no one was willing to try it for free). As he plunges through the tube, he relates scientific observations of gravity, temperature, and distance. At the end, the tunnel self-destructs, but the plucky volunteer lives through it, sells his story to a New York newspaper for $100,000, tours the country as a celebrated hero, and marries the inventor’s pretty daughter. Horatio Alger meets the hollow earth. But it’s another example of how writers of every period have used the notion for purposes appropriate to their time. The first attempts at building subways went back to the 1840s in London, where underground railways were first pioneered, but by the turn of the new century a certain mania for subway building was taking place in major cities worldwide. The first practical subway line in the United States was under construction in Boston while Fezandie was writing Through the Earth, as was New York’s (which would officially open in 1904), and it seems likely that Fezandie simply used these as a jumping-off point. Why not a really long one?

The Secret of the Earth by Charles Beale (1899) features two characters who have invented an airplane that they fly to the North Pole and into a Symmes’ Hole into the interior. They find a paradise that was mankind’s first home and then fly out through the hole in the South Pole. Their airship beats the Wright Brothers by four years, of course, but in the 1890s, trying to come up with one was all the rage with inventors. It’s often forgotten that the Wrights had serious competitors racing with them to develop a reliable design, and that one incentive was a large cash prize offered by France to the inventor of the first one that really worked—which is to say that the idea of airplanes was, well, in the air at the time Beale’s Secret of the Earth appeared.

William Alexander Taylor’s Intermere (1901) is like a bad rewrite of Symzonia. It too uses the hollow earth as a vehicle for current ideas. This otherworldly society has solved all earthly problems. It is a perfect democracy—almost. Women are supposedly equal, but their “chosen” role is generally that of housewife, and those who work don’t make as much money as men. They receive five fewer years of education than men do, and they’re not allowed to own real estate. But everybody’s pretty and handsome, nobody’s poor, there’s a four-hour workday, the communities are lovely and idyllic, crops go from planting to harvest in ten days, all marriages are happy and harmonious, and the food is fabulous but nobody has to cook. They have Medocars, Aerocars, and Merocars—autos, airplanes, and ships—which zip silently about at “a rate of speed that makes our limited railway trains seem like lumbering farm wagons.” They are powered by a force derived from electricity, which proves to be the secret behind their social and economic perfection.

The Intermerans also have a device that’s rather like an online fax machine. When the displaced narrator asks for news from home, his host goes to a cabinet and opens it: “Soon his hands began to move with rhythmic rapidity over the curiously inlaid center of the flat surface of the open cabinets. At the end of ten or fifteen minutes his manipulations ceased, a compartment noiselessly opened, and eight beautifully printed pages, four by six inches, bound in the form of a booklet, fell upon the table. The pages before me comprised a compendium of yesterday’s doings of the entire world.” In their opinion, surface events, which they keep close track of, are really stupid. “Selfishness, oppression, slaughter, pride, conquest, greed, vanity, self-adulation and base passions make up ninety-nine one-hundredths of this record,” sighs the host. This leads him into a tirade against surface world newspapers. He says this objective compendium “is to promote wisdom. The newspaper [exists] to feed vicious or depraved appetite, as well as to convey useful information. This is the cold, colorless, passionless record of facts and information, from which knowledge and wisdom may be deduced to some extent. Your newspaper is the opposite, taken in its entirety. It consists of the inextricable mingling together of the good and the bad, of the useful and the useless, and the elevating and the degrading, the latter always in the ascendant.”

Sounds like he’s been reading the papers, all right. In fact, this critique comes from someone who spent much of his career writing them. Taylor was an Ohio lawyer born in 1837 who turned to newspaper work in 1858, and was associated with various papers (chiefly the Cincinnati Enquirer) until 1900. So he knew the failings of American newspapers from the inside.

Gabriel de Tarde’s

Underground Man, first published in 1896, appeared in English translation in 1905 with a preface by H. G. Wells. This hollow earth novel by a French sociologist set in the thirty-first century is a satire on prevailing sociological thinking. It tells the story of how a near-utopia had been created on the surface, until the sun began sputtering out and dying, killing nearly all of mankind. Those remaining are driven beneath the surface, where they establish yet another utopia, bristling with thoroughly modern machines and techniques: thermal power, electric trains, monocyles, and other gizmos. But the main idea is that being driven underground has “produced, so to say, a purificaton of society.” It has, in effect, changed human nature. He writes:

Secluded thus from every influence of the natural milieu into which it was hitherto plunged and confined, the social milieu was for the first time able to reveal and display its true virtues, and the real social bond appeared in all its vigor and purity. It might be said that destiny had desired to make in our case an extended sociological experiment for its own edification by placing us in such extraordinarily unique conditions.... The mental space left by the reduction of our needs is taken up by those talents—artistic, poetic, and scientific—which multiply and take deep root. They become the true needs of society. They spring from a necessity to produce and not from a necessity to consume.

Worth noting is that this perfect society has been produced by “the complete elimination of living nature, whether animal or vegetable, man only excepted.” This idea of completely overcoming nature, subduing and totally dominating it, was one that had been growing during the nineteenth century. And how could it not, given the ceaseless succession of scientific and technical marvels that just kept unfolding? So in Underground Man de Tarde pushes such hubris to the limits, by getting rid of nature entirely!

The Smoky God (1908) by Willis George Emerson has a familiar structure but is more charming than many, thanks to the narrator’s voice, as told to Emerson, the putative editor. Ninety-five-year-old Norwegian Olaf Janson had this adventure in 1829 when he was a teenager, so the telling combines the innocence of a young boy with an old man’s nostalgia. Olaf and his father set off on a fishing voyage to the north in a small sloop and sail over the long gradual curve of a Symmes’ Hole into the interior. There they encounter a beautiful, verdant land lit and warmed by a reddish central sun—the smoky god—and peopled by a race of gentle giants who live to be six hundred years old. They’re twelve feet tall and dress like medieval Scandinavian peasants, with big gold buckles on their shoes—gold being common as beach pebbles there.

The argument for the existence of this inner paradise is the same one that Edmond Halley made over two hundred years earlier: it is demanded by God’s purpose and parsimony regarding waste. It had to be there. The Smoky God goes farther. The inner earth is “the cradle of the human race,” the original Eden. In fact, “God created the earth for the ‘within’—that is to say, for its lands, seas, rivers, mountains, forests and valleys, and for its other internal conveniences, while the outside surface of the earth is merely the veranda, the porch . . . in the beginning this old world of ours was created solely for the ‘within’ world.” It’s not so far from the beliefs of Cyrus Teed, except he thought we were all still inside.