“At the Earth’s Core,” published in All-Story magazine, which featured a pensive-looking Dian the Beautiful on the cover. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

7

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS AT THE EARTH’S CORE

THE NUMBER OF HOLLOW EARTH NOVELS dropped off drastically after 1910, largely because polar exploration revealed no Symmes’ holes. Consequently it was harder for readers (and writers) to create the suspension of disbelief needed to make such stories work. Something similar happened in the 1960s in regard to Venus. Its thick atmosphere and proximity to the sun had allowed generations of science fiction writers to create stories set in a steamy tropical wonderland of mysterious jungles and strange creatures. But then the facts intruded: under all those clouds Venus is too hot for life and too dry. And so the fetching bosomy Venusian maidens that routinely adorned pulp magazine covers from the 1930s through the 1950s disappeared. And although they didn’t disappear completely, stories set in the hollow earth began to seem too far-fetched once science established the geophysical impossibility of a hollow earth.

But one writer remained undaunted by facts to the contrary.

Edgar Rice Burroughs liked the idea of a hollow earth well enough to set six novels and several short stories in what he called Pellucidar, starting with At the Earth’s Core, first published serially in 1914 in All-Story Weekly.

Burroughs’s life before turning to writing at the age of thirty-five was like Baum’s compounded for the worse—a study in lack of direction and repeated failure. He was born into a prosperous Chicago family in 1875. His father was a wealthy whiskey distiller, which proved ironic given Burroughs’s later struggle with alcoholism. As a teenager he’d been sent to the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and was elected class president in 1892—but got yanked out of school by his father that same year for low grades and was forcibly relocated to the Michigan Military Academy north of Detroit, where he remained for five years. In 1896, he joined the army, but soon found himself bored stiff at the Arizona fort where he was stationed and began writing to his father, begging him to get him out. Special discharge papers signed by the secretary of war arrived early in 1897.

Years of upheaval followed. His brother Harry owned a cattle ranch in Idaho, and Burroughs’s first job after leaving the army was as a cowboy, helping his brother drive a herd of starving Mexican cattle from Nogales to Kansas City. By summer he had enrolled as a student at Chicago’s Art Institute, but it didn’t last. Early in 1898, with things heating up in Cuba, Burroughs wrote Teddy Roosevelt offering to join his Rough Riders—but was rejected. By June of that year he’d opened a stationery shop in Pocatello, Idaho, but he was back to cowboying with his brother the following spring, and then landed in Chicago again in June as treasurer of his father’s American Battery Company—the distillery burned down in 1885, and his father, resilient, had shifted to supplying the nascent automobile industry.

Burroughs married Emma, his longtime sweetheart, in 1900, and stayed with dad’s battery company for three more years—but then a roller-coaster ride of jobs followed. By then he was beginning to do some writing and cartooning, but hadn’t figured out how to make a living at it. He joined his brother Harry in an Idaho gold dredging operation in 1903, but that went bust in less than a year. On to Salt Lake City, where he became a railroad policeman for a time, and then it was back to Chicago. There, for the next seven years, poor Burroughs tried everything he could think of to support Emma and his growing family: high-rise timekeeper, door-to-door book salesman, lightbulb salesman, accountant, manager of the stenographic department at Sears, partner in his own short-lived advertising agency, office manager for a firm selling a supposed cure for alcoholism called Alcola, and a sales agent for a pencil sharpener company. This last job involved monitoring ads in pulp magazines—but Burroughs found himself more interested in reading the stories in these magazines than the ads he was supposed to be tracking. And the lightbulb lit. I can do this! In 1911, as the company was heading under, using the backs of letterhead stationery from his former failed businesses, Burroughs began handwriting what became Under the Moons of Mars, featuring John Carter, the first of his invincible heroes. He sent it out, and in August came a letter of acceptance from the editor of All-Story. Though Burroughs was still writing in his spare time—or stealing time from his latest job, working for brother Coleman’s stationery manufacturing company on West Kinzie Street, Chicago—by December 1911, he’d started writing Tarzan of the Apes, which he also sold to All-Story (for $700).

He began work on the first of his Pellucidar novels in 1912 while the manuscript of Tarzan of the Apes was still making the rounds of book publishers, collecting rejection slip after rejection slip as it went. His working title was “The Inner World.” All-Story ran it serially in four issues starting on April 4, 1914. It didn’t appear as a book until 1922, when A. C. McClurg, Burroughs’s publisher for many years, brought it out with a wonderful cover, both menacing and sexy, by J. Allen St. John, the best illustrator of Burroughs’s early work.

The first edition of At the Earth’s Core (1922) was illustrated by J. Allen St. John; the cover shows David Innes rescuing Dian the Beautiful. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

His hollow earth story’s most obvious debt was to Jules Verne’s novel A Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864). Another likely influence was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, which was a best seller in 1912. In Doyle’s novel, the lost world, discovered by British explorers, lay not in the hollow earth but on a vast plateau surrounded by cliffs rising above the South American jungle, isolated for eons, unchanged since the Jurassic Period. This remote, unapproachable tableland was crawling with prehistoric life—huge, scary dinosaurs in particular. The clashing prehistoric reptiles in Verne’s Journey played only a minor part in the novel overall. As we’ve seen, dinosaurs had captured the popular imagination ever since their “invention” in the early nineteenth century and the coining of the term by Sir Richard Owen in 1841. Life-size reconstructions featured at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London (and the splashy formal dinner thrown by sculptor/promoter Waterhouse Hawkins inside a half-constructed Iguanodon) cemented popular interest, which Verne drew on for his prehistoric novel.

In 1884 the discovery of a fossil herd of articulated Iguanodon skeletons in a Belgian coal mine further heightened dinosaurmania, as did the 1886 publication of Le monde avant la creation del ’homme, by Camille Flammarion (1842–1925), which pictured an Iguanodon rampaging in the streets of Paris—the precursor to all those Godzilla movies. In the late 1890s, the New York Museum of Natural History bought famed dinosaur hunter Edward Drinker Cope’s collection and commenced creating dramatic displays that were enthusiastically attended. Dinosaurs hadn’t been used much in literature except by Verne, and then only in a minor role. In The Lost World they take center stage for the first time. Although Verne was the first to use them in fiction, the real origins of our ongoing pop cult love affair with dinosaurs—which reached an apotheosis of sorts in the Jurassic Park movies—can be traced to Doyle’s novel, which remains so popular that an adventure series based on it ran for several years on television starting in 1999. While The Lost World was still on top of the best-seller lists, Burroughs was casting around for a new writing project. He seems to have combined Verne’s hollow earth premise with Doyle’s teeming prehistoric world, adding quite a few brainstorms of his own.

The landscape, ecology, and cosmology of Pellucidar are delightfully wacky and definitely all-American, starting with the way mining magnate David Innes and inventor Abner Perry got there: in an experimental mining machine run amok. Perry has invented an “iron mole,” a “mechanical subterranean prospector” consisting of “a steel cylinder a hundred feet long, and jointed so that it may turn and twist through solid rock if need be. At one end is a mighty revolving drill.” It’s a sort of segmented steam locomotive with a huge Roto-Rooter attached to the front. Burroughs may well have been inspired to create this curious device based on his gold mining days, and also by reading the

Chicago Tribune comics page. Dale R. Broadhurst says in an article in

ERBzine, A likely source for the “Iron Mole” may be found in 1910 issues of the Sunday

Chicago Tribune, where cartoonist M. L. Wells chronicled in color his “Old Opie Dilldock’s Stories.” In one of these 1910 illustrated Sunday full-pages, Opie plans a trip to the south pole and constructs an “earth borer” in his secret workshop, in order to make the trip there by way of a straight line through the Earth. Utilizing a hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell for power, the ingenious inventor propels his contraption to “the center of the earth.” There he discovers strange intelligent beings . . . one of which he takes with him on his return to the planet’s surface. While I doubt very much that Edgar Rice Burroughs sat down with a pile of “Opie Dilldock’s Stories,” in order to write out his 1913 “Inner World” adventure, some story elements from this set of locally published cartoons may well have entered into the would-be author’s inner fantasies, and from there flowed out onto his pages of fiction, probably more by happenstance than through his conscious design.

63Innes and Perry have built this machine not to advance knowledge and exploration, but to extend the frontiers of coal mining beyond those of mortal men—and make tons of money while they’re at it. But on its trial run, the steering freezes and the damn thing won’t stop—commencing to bore its way like crazy straight for the center of the earth.

After tearing through five hundred miles of rock, the iron mole pops out in sunny, tropical Pellucidar. “Together we stepped out to stand in silent contemplation of a landscape at once weird and beautiful.” But in nothing flat, “there came the most thunderous, awe-inspiring roar that ever had fallen upon my ears.” It’s a colossal bearlike creature the size of an elephant—a dyryth—and it’s after them. But it’s distracted by the sudden appearance of a wolf pack a hundred strong, quickly followed by their masters, black “manlike creatures” with dracula teeth and long, slender tails, “grotesque parodies on humanity.” These are but one of several races of varying intelligence inhabiting Pellucidar. They capture Innes and Perry and race through the treetops to their arboreal bough-village high in the trees.

Pellucidar is a busy, complicated place. As the ERBzine puts it, “The land teems with plant and animal life. A veritable melting pot where animals of nearly all the geological periods of the outer crust exist simultaneously. The land’s races are just as varied as its animal life.” Burroughs seems to have adopted the kitchen sink theory of the hollow earth, throwing in everything he can think of. More is more.

Innes and Perry escape from the tree creatures only to be captured by another vaguely hominid species called the Sagoths. They look like gorillas and are slave masters to yet another species—Stone Age humans. Innes and Perry are added to the chain gang and get to know a few of the enslaved humans—Ghak the Hairy One, Hooja the Sly One, and Dian the Beautiful. They’re on a forced march to the village of the evil Mahars.

The dominant species on Pellucidar, the Mahars are a master race of super-intelligent lizards. They “are great reptiles, some six or eight feet in length, with long narrow heads and great round eyes. Their beaklike mouths are lined with sharp, white fangs, and the backs of their huge lizard bodies are serrated into bony ridges from their necks to the end of their long tails, while from the fore feet membranous wings, which are attached to their bodies just in front of the hind legs, protrude at an angle of 45 degrees toward the rear, ending in sharp points several feet above their bodies.”

Voiceless and unable to hear, the Mahars “communicate by means of a sixth sense which is cognizant of a fourth dimension.” Whatever that may mean. Their capital is an underground city called Phutra, where they’re served by the gorilla-like Sagoths and keep crowds of humans as cattle, since the Mahars consider human flesh quite a delicacy. They enjoy watching Roman-style combat in their great amphitheater between vicious beasts and lowly humans, on whom they also perform “scientific” experiments à la Joseph Mengele. A really nasty bunch, the Mahars, sort of like brainy flying Komodo dragons with Nazi proclivities.

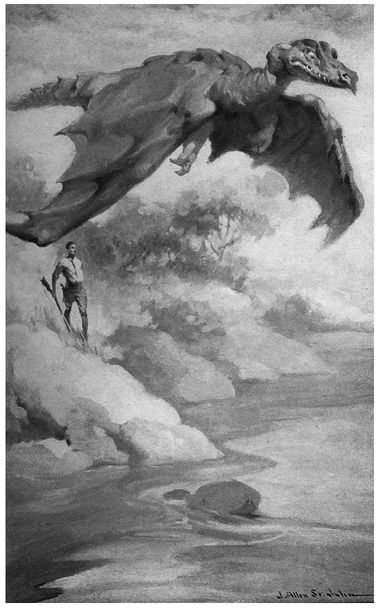

A Mahar in flight, in a drawing by St. John from the first edition of At the Earth’s Core. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

But oddest about them—and telling in regard to Burroughs, whether he intended it or not—is that the Mahars are an all-female society. These reptilian incarnations of evil are all girls! Like the Mizorans, many generations ago the Mahars learned how to procreate without the unnecessary complication of having males around—“a method whereby eggs might be fertilized by chemical means after they were laid.” The implication, however unintentional, is that the twisted evil Mahars are what you get if women are left to their own devices. There’s a definite undercurrent of misogyny here, despite all the praises heaped on noble, pure-as-the-driven-snow Dian the Beautiful (whose characterizing epithet is also revealing in regard to Burroughs’ ideas about women—she’s not Dian the Smart, or Dian the Resourceful, or Dian the Independent).

The secret of the Mahars’ parthenogenesis is kept in a single book stored in a vault deep beneath Phutra. There’s only one copy, and none of the high-I.Q. Mahars seems to have memorized the formula, which gives Perry an idea. As they wait around in their cell, Perry prays continually and has a flash: “David, if we can escape, and at the same time take with us this great secret, what will we not have accomplished for the human race within Pellucidar!”

“Why, Perry! You and I may reclaim a whole world! Together we can lead the races of men out of the darkness of ignorance into the light of advancement and civilization. At one step we may carry them from the Age of Stone to the twentieth century.”

“David, I believe that God sent us here for just that purpose!”

“You are right, Perry. And while you are teaching them to pray I’ll be teaching them to fight, and between us we’ll make a race of men that will be an honor to us both.”

Note the grandiosity—they’ll be doing this to honor themselves. Probably just hasty, imprecise writing (at another point Burroughs has a character say he won’t “stand supinely” watching), but also revealing of what’s to come.

By this time Perry has figured out Pellucidar’s cosmology. Its provenance encompasses hollow earth thinking going all the way back to Edmond Halley. Centrifugal force has caused the hollowness. As the spinning earth cooled, matter was thrown out to the edges, except for a “small superheated core of gaseous matter” that remained in the center as Pellucidar’s never-setting sun. This is a slap in the face of Newtonian physics, of course, since a sun existing in the center of the earth would either burn the whole globe to a cinder, and/or its gravity would cause the hollow sphere to collapse. But it’s both futile and somehow unfair to insist on plausibility in such a mixed bag of fantasy. There is no mention of a polar opening in At the Earth’s Core, but Burroughs uses it in the third book, Tanar of Pellucidar, to explain the presence of the dastardly Korsars, yo-ho-ho descendants of seventeenth-century Spanish pirates who accidentally sailed over the rim into Pellucidar and have been wreaking havoc there ever since. He also uses the polar opening in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core to get Tarzan down there to help rescue David Innes, who’s been captured for about the nineteenth time.

Since the interior cooled more slowly than the surface, life started later on Pellucidar, making it “younger” than our world—thus all the prehistoric flora and fauna running riot there. The weird twists life has taken on Pellucidar can be explained by alternate evolution. Life forms from different geologic periods exist simultaneously owing to the absence of the cataclysms that have affected life on the surface. Pellucidar has considerably more land; the proportions of ocean to earth are reversed, so that the land area there is three times greater than above, “the strange anomaly of a larger world within a smaller one!” But the greatest anomaly—which Burroughs never successfully explains—is that time doesn’t exist on Pellucidar. Nobody can tell how long anything takes. It’s supposedly because the sun never sets, but why that would make a difference defies explanation, even though Burroughs insists on it again and again, in book after book. Why this was so important to his conception of Pellucidar is a mystery. But it’s his world, and he can do what he wants.

Toward the end of At the Earth’s Core, after his second escape from the Mahars, while wandering through uncharted territory, Innes comes on a lovely valley that he describes as a “little paradise.” The chapter is titled “The Garden of Eden.” But Eden wouldn’t be complete without an Eve—or a serpent of sorts. Innes comes across a girl standing terrified on a ledge—his long-lost Dian the Beautiful—who’s being attacked by “a giant dragon forty feet in length,” with “gaping jaws” and “claws equipped with terrible talons.” Never a dull moment on Pellucidar. Innes saves her, realizing, finally, that he loves her. Their brief idyll is interrupted by Jubal the Ugly One, who’s been sniffing after Dian from the beginning. In their bloody duel to the death, crafty Innes prevails and has an inspiration in the moment of triumph: “If skill and science could render a comparative pygmy the master of this mighty brute, what could not the brute’s fellows accomplish with the same skill and science. Why all Pellucidar would be at their feet—and I would be their king and Dian their queen.”

The sociopolitics of Pellucidar from here on are an eccentric amalgam of Arthurian legend, liberal Progressivism, and Teddy Roosevelt–style speak-softly-and-carry-a-big-stick democratic imperialism—an ideological stew representing Burroughs’s own jumbled worldview.

Innes and Dian make their way back to Sari, her homeland, and in nothing flat everyone agrees to his plan. An intertribal council is called and “the eventual form of government was tentatively agreed upon. Roughly, the various kingdoms were to remain virtually independent, but there was to be one great overlord, or emperor. It was decided that I should be the first of the dynasty of the emperors of Pellucidar.”

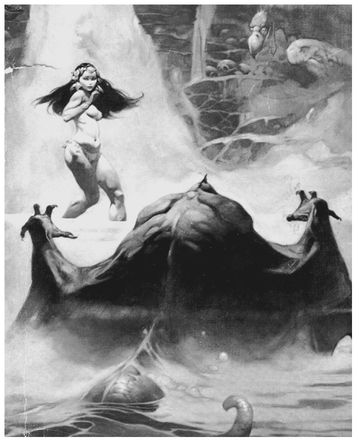

Dian the Beautiful as shown being menaced by Mahars on this 1970s Ace Paperback cover by Frank Frazetta. (© Frank Frazetta)

His goal? Freedom for enslaved humanity, achieved by the extermination of the Mahars. “How long it would take for the race to become extinct was impossible even to guess; but that this must eventually happen seemed inevitable.”

And how would this ethically dubious end be achieved? Superior weaponry. Perry has been experimenting with “various destructive engines of war—gunpowder, rifles, cannon and the like” but hasn’t been as successful as he hoped. Still, “we were both assured that the solution of these problems would advance the cause of civilization within Pellucidar thousands of years at a single stroke.”

In bringing civilization to Pellucidar, they plan to start with guns and genocide.

Innes will make a return trip to the surface in the iron mole to bring back weapons—along with books on such useful subjects as mining, construction, engineering, and agriculture. An arsenal of information to bring Pellucidar into the twentieth century, for better or worse. Works of literature do not appear on the wish list.

“What we lack is knowledge,” Perry exclaims. “Let us go back and get that knowledge in the shape of books—then this world will indeed be at our feet.” Yet another revealing slip. For all their supposed humanitarianism, Perry and Innes talk like megalomaniacs.

Innes plans to take Dian to the surface with him and show her the sights, but Hooja the Sly One, living up to his cognomen, pulls a switch, and Innes finds himself boring headlong upward with a creepy Mahar as a companion, not Dian the Beautiful. The iron mole comes out in the Sahara, and the novel ends with Innes and the bewildered Mahar waiting for someone to find them.

Nearly two years passed before Burroughs began work on Pellucidar, the second book in the series. Innes returns to Pellucidar in the iron mole with its cargo of guns and knowledge, but the steering still isn’t working right, so when he gets there, he’s lost. More captures, escapes, battles with terrible creatures. Hooja is on a rampage; he has raised a rebel force and has again kidnapped Dian. Innes is paddling away from Hooja’s ships in a small dugout. All seems hopeless, as usual, when the empire’s new fleet, fifty ships strong, sails onto the scene and defeats Hooja’s inferior forces. Ecstatic, Innes cries, “It was MY navy! Perry had perfected gunpowder and built cannon! It was marvelous!” They cream Hooja’s inferior forces. Plans for the empire shift into high gear and progress, of a sort, strikes poor Pellucidar.

Like every boy of his time, Burroughs grew up on the medieval romances of Sir Walter Scott, but unlike most, he apparently hadn’t outgrown them by 1915—at the age of forty. Part of his charm, I guess. It seems safe to consider Innes an alter ego for Burroughs, and he indulges in some knights-in-shining-armor dreamin’ here. After the battle, Emperor David’s “fierce warriors nearly came to blows in their efforts to be among the first to kneel before me and kiss my hand. When Ja kneeled at my feet, first to do me homage, I drew from its scabbard at his side the sword of hammered iron that Perry had taught him to fashion. Striking him lightly on the shoulder I created him king of Anoroc. Each captain of the forty-nine other feluccas I made a duke. I left it to Perry to enlighten them as to the value of the honors I had bestowed upon them.”

Perry updates Innes on the improvements he’s made at Sari. Everyone has joined the cause against the Mahars, but beyond that Perry says, “they are simply ravenous for greater knowledge and for better ways to do things.” They mastered many skills quickly, and “we now have a hundred expert gun-makers. On a little isolated isle we have a great powder-factory. Near the iron-mine, which is on the mainland, is a smelter, and on the eastern shore of Anoroc, a well equipped shipyard.”

So the Pellucidarians, in a single bound, have leaped into the Industrial Age, and have been introduced to the joys of mines scarring the landscape, factories billowing smoke, and long, tedious work days.

Innes responds, “It is stupendous, Perry! But still more stupendous is the power that you and I wield in this great world. These people look upon us as little less than supermen. We must give them the best that we have. [You can practically hear the patriotic music begin to swell and see the flag proudly flapping in the breeze.] What we have given them so far has been the worst. We have given them war and the munitions of war. But I look forward to the day [music really swelling now, possibly a visionary tear in his eye] when you and I can build sewing machines instead of battleships, harvesters of crops instead of harvesters of men, plow-shares and telephones, schools and colleges, printing-presses and paper! When our merchant marine shall ply the great Pellucidarian seas, and cargoes of silks and typewriters and books shall forge their ways where only hideous saurians have held sway since time began!”

But before this grand vision can be realized, first they have to deal with those “haughty reptiles”—the evil Mahars. A council of kings convenes and decides to commence “the great war” against them immediately.

As Burroughs was writing this in January 1915, the real Great War was spreading like a terrible brushfire on the surface. In 1912–1913 small wars in the Balkans had begun bursting into flames out of seeming spontaneous combustion. Then on June 28, 1914, Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo. By summer’s end, declarations of war flying like dark, dry leaves, country after country found itself involved, and within months the fighting was burning its way through Europe with a ferocity unprecedented in history.

One might expect to see at least a glimmer of these events in “the great war” against the Mahars; and there is, though not much more, beyond the fact that Burroughs decided to make it part of the story in the first place. The main parallel is that Emperor David quickly gains many allies—nearly all the known tribes of Pellucidar are united for the first time against one enemy. The plan? “It was our intention to march from one Mahar city to another until we had subdued every Mahar nation that menaced the safety of any kingdom of the empire”—starting with Phutra, the Mahar capital.

The Battle of Phutra is a pretty good one. Burroughs didn’t entirely waste those years in military school and the army. A phalanx of Sagoths and Mahars engages the Empire’s forces outside the city but is “absolutely exterminated; not one remained even as a prisoner.” On to the city and its “subterranean avenues,” where the allies are temporarily stymied—the morally corrupt Mahars are using poison gas. But Perry jury-rigs a few cannon bombs, dumps them down the holes like oversize grenades, and blam! Mahars by the hundreds come streaming out of their underground lair like dazed wasps and, taking wing, flee to the north. After the fall of Phutra, victory follows victory—the Mahars are less tenacious than the Germans. Emperor David’s armies march “from one great buried city to another. At each we were victorious, killing or capturing the Sagoths and driving the Mahars further away.” The menace isn’t eliminated—“their great cities must abound by the hundreds and thousands [in] far-distant lands”—but they’ve at least been forced far from the Empire.

At the end of Pellucidar, David and Dian settle in to enjoy royal life in their “great palace overlooking the gulf.” Perry is working like a beaver on further “improvements,” laying out a railway line to some rich coalfields he wants to exploit. Sea trade between kingdoms proceeds apace, the profits going “to the betterment of the people—to building factories for the manufacture of agricultural implements, and machinery for the various trades we are gradually teaching the people.”

Today we have nearly a hundred years of hindsight to wonder about the ultimate value of what Burroughs clearly sees as progress for Pellucidar. As Emperor David sums it up at the novel’s close, “I think that it will not be long before Pellucidar will become as nearly a Utopia as one may expect to find this side of heaven.”

Burroughs took fourteen years off from writing about Pellucidar, but in 1928–1929, in a burst, he produced Tanar of Pellucidar and Tarzan at the Earth’s Core. Both represented a falling-off from the earlier books. Whatever improbable coherence this inner territory had in the first two begins flying apart in these. Pellucidar increasingly seems less an intact world than an imperfect collection of shards, broken pieces lacking cohesion. Part of this is due to overcomplication. Savage countries, races, and creatures multiply like prehistoric rabbits in Burroughs’s attempts to ever increase the excitement by concocting yet another new kind. As Brian W. Aldiss observes in Billion Year Spree, “Burroughs never knew when enough was enough.” Just among the races, by series end there are Stone Age men, Sagoths (gorilla men), Mahars (brainy evil reptiles), Horibs (lizard or snake men), Ganaks (bison men, humanoid bovines), Gorbuses (humanoid cannibalistic albinos), Coripies (or Buried People; blind underground dwellers with no facial features, large fangs, webbed talons), Beast Men (savage vegetarians with faces somewhere between a sheep and a gorilla), Ape Men (black hairless skins, long tails, tree dwelling), Sabretooth Men, Mezops (copper-colored island dwellers), Korsars (descendants of pirates who accidentally sailed into the polar opening), Yellow Men of the Bronze Age—and I may be leaving some out. The overcomplication diminishes their impact. It is impossible to keep all these creatures and their various domains straight, and it’s arguable whether or not Burroughs managed to do so himself. With all these races always at odds with each other, there’s a growing feeling of fragmentation. Here in the center of the earth there’s no center, as one or the other of these squabbling races takes the stage to provide trouble for our various heroes, and everything else all but disappears from view. In both Tanar and Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, for instance, the evil Mahars, the chief scourge of Pellucidar in the first two novels, are hardly mentioned, even though they were only driven off, not exterminated as Perry had hoped. And the Empire that Perry and Innes have forcibly cobbled together also remains far offstage in these later two novels. Most of Tanar, essentially a rock ’em sock ’em adventure-filled love story between the title character and imperious Stellara, takes place among the Korsars, and in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, everybody spends most of their time lost in the jungle, fighting off one or another prehistoric monster—which Burroughs multiplies right along with the savage races. Especially in Tarzan at the Earth’s Core there’s a sameness to the attacks, captures, escapes, followed by more attacks, captures, and escapes—as if Burroughs were operating more on autopilot than not.

Cover art for Tanar of Pellucidar, the third Pellucidar novel. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

Splendid St. John cover for Tarzan at the Earth’s Core. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)

In

Tarzan at the Earth’s Core, young Jason Gridley of Tarzana, California, has a special radio that receives signals from Pellucidar. He hears that David Innes has been captured by the Korsars and is being held captive by them, and decides that only Tarzan can free him. Gridley goes to Africa to plead his case, saying that he’s just learned about an opening at the pole that leads to Pellucidar. Tarzan says, hmm, we’ll need a Zeppelin, and just happens to know of an ultralight, ultrastrong metal in nearby mountains that no one else has discovered, so they have a bunch of it mined and go to Germany to construct the airship. As the Zeppelin drops through the polar opening and drifts lower toward Pellucidar’s surface, Tarzan looks approvingly over the landscape and exclaims, “This looks like heaven to me.” As soon as they land, Tarzan decides to take a jungle stroll, and doesn’t reconnect with the others until the book’s end, when almost as an afterthought Innes is sprung from the Korsars’ captivity. Tarzan wasn’t kidding about heaven. Pellucidar is even more unspoiled and primitive than his own jungle at home. And Tarzan loves it:

In the first flight of his newfound freedom Tarzan was like a boy released from school. Unhampered by the hated vestments of civilization, out of sight of anything that might even remotely remind him of the atrocities with which man scars the face of nature, he filled his lungs with the free air of Pellucidar, leaped into a nearby tree and swung away through the forest, his only concern for the moment the joyousness of exultant vitality and life. On he sped through the primeval forest of Pellucidar. Strange birds, startled by his swift and silent passage, flew screaming from his path, and strange beasts slunk to cover beneath him. But Tarzan did not care; he was not hunting; he was not even searching for the new in this new world. For the moment he was only living.

This is a beautiful existential moment, in some ways a crystallization of the ethos running throughout all of Burroughs’s work. Tarzan is somewhere else, in a place of beauty and adventure, with no noise or bus fumes or electric bills—or responsibilities. Born free . . .

Seconds after this peaceful epiphany,

thwap! Tarzan is caught in a rope snare, and finds himself hanging upside down, slowly spinning, as a ferocious sabretooth tiger slinks toward him. But even facing death, Tarzan is not afraid. “He had looked upon death in so many forms that it held no terror for him.” He is, however, moved to rare metaphysical introspection. The interior lives of Burroughs’s characters go largely unexplored beyond visceral reactions to whatever the situation is at hand. But here, dangling, about to be a sabre-tooth’s lunch, Tarzan thinks of First and Last Things. It’s the closest to a spiritual creed I’ve found in the Tarzan books and presumably isn’t too far from Burroughs’s own views on these matters:

Tarzan of the Apes would have preferred to die fighting, if he must die; yet he felt a certain thrill as he contemplated the magnificence of the great beast that Fate had chosen to terminate his earthly career. He felt no fear, but a certain sense of anticipation of what would follow after death. The Lord of the Jungle subscribed to no creed. Tarzan of the Apes was not a church man; yet like the majority of those who have always lived close to nature he was, in a sense, intensely religious. His intimate knowledge of the stupendous forces of nature, of her wonders and her miracles had impressed him with the fact that their ultimate origin lay far beyond the conception of the finite mind of man, and thus incalculably remote from the farthest bounds of science. When he thought of God he liked to think of Him primitively, as a personal God. And while he realized that he knew nothing of such matters, he liked to believe that after death he would live again.

Maybe it’s just as well Burroughs kept this sort of thing to a minimum. Tarzan reveals a sort of homegrown deism combined with a vaguely born-again fundamentalism—Thomas Jefferson meets George Bush. Naturally Tarzan doesn’t have to worry about the next life because just as the sabre-tooth strikes, upsy-daisy —the Sagoths who had set the snare yank him upward into the trees.

We get another glimpse into Burroughs’s attitudes a little farther on from young Jason Gridley, who’s cowering in a tree himself, watching “hundreds” of sabre-tooths slaughtering the game they’ve herded into a deadly roundup circle. Gridley sees in this a development of intelligence on the cats’ part that will lead to their extinction—in their cunning savagery they will eventually wipe out all their prey, and then turn on each other—which leads him to reflect on the future of mankind:

Nor did Jason Gridley find it difficult to apply the same line of reasoning to the evolution of man upon the outer crust and to his own possible extinction in the not far remote future. In fact, he recalled quite definitely that statisticians had shown that within two hundred years or less the human race would have so greatly increased and the natural resources of the outer world would have been so depleted that the last generation must either starve to death or turn to cannibalism to prolong its hateful existence for another short period . . . What would be next? Gridley was sure that there would be something after man, who is unquestionably the Creator’s greatest blunder, combining as he does all the vices of preceding types from invertebrates to mammals, while possessing few of their virtues.

Italics mine. This pessimistic blast comes out of the blue, and has a ring of conviction, all the more so because it seems so uncharacteristic of youthful gung-ho boy scientist Gridley, and feels like a peek behind the curtain into Burroughs himself. Burroughs, among his often wacky enthusiasms, was an early Greenie, ahead of his time in realizing the earth’s fragility. He gave a speech on ecology to a group on Arbor Day, 1922, and discussed conservation issues in a 1930 radio interview, so it was a lifelong concern. And “the Creator’s greatest blunder” business—well, Burroughs carried a weight of bitterness despite his huge popular success. His drive to produce—writing, movie ideas, moneymaking schemes, endless Tarzan spin-offs (among them comic strips, kids’ clubs, Tarzan bread, Tarzan ice cream cups, Tarzan belts, Tarzan bathing suits, Tarzan jungle helmets, Tarzan yoyos, Tarzan candy, etc., etc.) has in it a nervous mania, a constant thirsty seeking for something that none of this frantic activity ever managed to quench. In 1934 as his long marriage to Emma crumbled, largely due to her drinking, compounded by his own fondness for the stuff, he decided learning to fly would be just the thing, commenced taking lessons, and bought his own airplane, while also courting Florence Ashton, his second wife-to-be, and scribbling away (well, dictating away) at his nineteenth Tarzan novel, Tarzan and Jane (Tarzan’s Quest), which on completion on January 19, 1935, was rejected by Liberty, Collier’s, and others before Blue Book finally bought and began serializing it in October. It’s interesting that just as the Tarzan manuscript was being rejected, Burroughs turned again to Pellucidar, starting on Back to the Stone Age in late January. Possibly just a coincidence, but possible, too, that thinking about Pellucidar was a pleasant retreat for him, more fun than grinding out yet more Tarzan. (He said in a 1938 radio interview that he had originally planned to write only two Tarzan novels.) Back to the Stone Age marks a further drop in quality. A long flashback to the Tarzan expedition, it relates the adventures of Von Horst, a crew member who becomes separated from the others. However, Von Horst’s story is anything but memorable—just another sequence of near-death scrapes, captures, and escapes, with the usual beautiful prehistoric maiden as a love interest. This manuscript collected rejection slip after rejection slip before being bought by Argosy magazine for $1,500 and serialized as Seven Worlds to Conquer from January 9 through February 13, 1937, then published in book form under its original title by ERB in September of that year.

In 1938 Burroughs again returned to Pellucidar, writing the 60,000 words of Land of Terror between October and April 1939 while juggling other projects. The story was rejected by every magazine it was sent to. It wasn’t published until 1944, when it appeared as a book under ERB’s own imprint.

Land of Terror is told by David Innes, who begins by reflecting on how old he and Perry are, something that may have been on the author’s mind, since he was sixty-three while writing this amiable nonsense, still churning it out. David is on his way back home to Sari with some of his minions as the story opens, and, wouldn’t you know it, they are attacked as they’re crossing a river, and captured. “They were heavy-built, stocky warriors with bushy beards, a rather uncommon sight in Pellucidar where most of the pure-blood white tribes are beardless.” Odder still, “As I looked more closely at my bearded, hairy captors, the strange, the astounding truth suddenly dawned upon me. These warriors were not men; they were women.” One of these he-women comments, “Who wants any more men? I don’t. Those that I have give me enough trouble—gossiping, nagging, never doing their work properly. After a hard day hunting or fighting, I get all worn out beating them after I get home.”

Yes, we’re hearing an echo of

Pantaletta, with Burroughs indulging in the same role-reversal comedy found in the earlier novel, without superior results. Innes is dragged to Oog, their primitive village, where he encounters “a hairless, effeminate little man,” the husband of Gluck, the leader, she of the “legs like a pro-football guard and ears like a cannoneer.” Away from the women, hubby and a few other men grouse about the women. “‘If I were bigger and stronger than Gluck, I’d beat her with a stick every time I saw her.’ ‘You don’t seem very fond of Gluck,’ I said. ‘Did you ever see a man who was fond of a woman?’ demanded Foola. ‘We hate the brutes.’” David is tossed under guard into a hut, where he meets Zor, a fellow prisoner, who tells him, “‘They have none of the natural sensibilities of women and only the characteristics of the lowest and most brutal types of men,’” another sentiment that might be straight out of

Pantaletta. A few sleeps later (no one ever knows what time it is in Pellucidar) David, slaving and starving in Gluck’s garden, can’t resist grabbing a tuber and gnawing ravenously on it. This enrages a female sentry, but he manages to coldcock her before she can do him in with her bone knife. Gluck turns up, angered that the sentry tried to beat one of her men, and they struggle—until at last Gluck kills the other woman. David watches it all and is moved to philosophy:

There followed one of the most brutal fights I have ever witnessed. They pounded, kicked, clawed, scratched and bit one another like two furies. The brutality of it sickened me. If these women were the result of taking women out of slavery and attempting to raise them to equality with man, then I think that they and the world would be better off if they were returned to slavery.

One of the sexes must rule; and man seems temperamentally better fitted for the job than woman. Certainly if full power over man has resulted in debauching and brutalizing women to such an extent, then we should see that they remain always subservient to man, whose overlordship is, more often than not, tempered by gentleness and sympathy.

At the time Burroughs’s second marriage was in trouble. And despite his tireless effort and the ubiquity of Tarzan (published in thirty-five countries, translated into fifty-eight languages), he still struggled financially; the dark shadows of the coming war were falling as well over his little empire and sales were dropping. Soon paper rationing and shortages would force major cutbacks in his book publications. Perhaps worse, Burroughs was losing faith in himself as a writer. I can think of no other writer of his established popularity whose work was so routinely rejected; and it galled him, too, that he was little more than a joke to the literary community—his would-be peers. All this wore on him, led him into bouts of depression and the dubious fleeting solace of whiskey. In June 1939 Florence underwent major surgery, and, in August of that year, primarily to cut down expenses, they decided to move to Hawaii. Then in November Burroughs suffered several minor heart attacks. Arriving in Hawaii in April 1940, Florence seems to have hated it from the start, possibly since they had left a fairly luxurious Beverly Hills apartment for a scruffy Hawaiian beach shack also semi-inhabited by rats and scorpions. Burroughs made the garage his office. Friends began noticing the tension between him and Florence, along with signs of increased drinking on Burroughs’s part. Still he amassed stacks of pages, knocking off a new Pellucidar short story, “Hodon and O-AA,” in one week during September.

Burroughs would live until 1950, but for all practical purposes his writing career sputtered to an end right here. He would continue to write the occasional Tarzan novel or stray short story, but never again at the manic pace he had maintained since 1911. The marriage to Florence ended in March 1941 when she and the children sailed back to California; they were divorced and she remarried not long afterward. Depressed, turning even more to the bottle, he gained a reprieve of sorts when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941—soon he had gotten himself a gig as a war correspondent, and spent the war years reporting from all over the Pacific. After the war he moved back to the L.A. area, but his health was so shattered by angina, Parkinson’s, and arteriosclerosis that from 1947 on, when he bought his first television set, he spent much of his time in front of it watching sports. In 1948 he experienced severe painful angina. As the Hillman site puts it, “When the nitro-glycerine doesn’t work he turns to bourbon. Over the coming months there is a reliance on bourbon for all ills.” He spent much of 1949 rereading all his books—”to see what I had said and how I’d said it.” He died March 19, 1950, after breakfast in bed, while reading the Sunday comics. Shortly before his death he said, “If there is a hereafter, I want to travel through space to visit the other planets”—a dreamy kid to the very end.

Burroughs’s final (and forgettable) tales of Pellucidar were published in the early 1940s, in a sci-fi pulp magazine called Amazing Stories, then newly under the editorship of Ray Palmer—who in 1945 began using his magazine to create a major league flap about the hollow earth that came to be known as “The Shaver Mystery.”

These Ace paperbacks from the 1960s of the Pellucidar series, published decades after they were written, are tangible examples of its continuing appeal. (© Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.)