10

THE ANGLO-NORMAN PERIOD

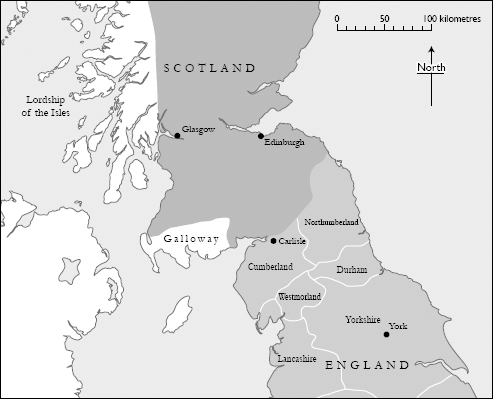

MAP 17 Southern Scotland and northern England in the late twelfth century

The county of Cumberland

Gospatric’s Writ suggests that the southernmost portion of the kingdom of Strathclyde, the region between the Solway Firth and the River Eamont, was restored to English rule sometime around the middle of the eleventh century. Earl Siward, who was probably the architect of this reconquest, seems to have appointed Northumbrians such as Gospatric to positions of authority previously held by Cumbrian lords who answered to the kings of Strathclyde. The English king Edward the Confessor thus gained a strategic foothold in the north-west, on the edge of the volatile Irish Sea zone. In the ensuing redistribution of estates, many of the boundaries established in the era of Cumbrian rule were respected and preserved. Gospatric’s great lordship of Allerdale, for example, almost certainly originated as a British territorial unit in the tenth century. One change introduced by the English after their takeover was the splitting of large estates into smaller ones which were often named after the beneficiary of the division. This process has left its mark on modern maps, where the new estates are indicated by place-names in which a personal name is followed by the Danish suffix -by.1 Such names do not appear to belong to an earlier period of Scandinavian settlement and are seen as creations of the eleventh century. They probably reflect a landholding pattern first introduced by Siward’s Anglo-Danish henchmen who crossed the Pennines from the earldom of York. The pattern was later continued by the Normans when they consolidated their hold on the region in the 1100s.2

Siward died in 1055 and was succeeded as earl of Northumbria by Tostig Godwinesson whose brother Harold hoped to succeed Edward the Confessor as king of England. After Edward’s death in 1066, Duke William of Normandy invaded England and destroyed Harold at the battle of Hastings. Tostig was already dead, having been slain three weeks earlier at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire where, in alliance with King Harald Hardrada of Norway, he had marched against his own brother. In the wake of Harold Godwinesson’s death, William became the first Norman king of England and the founder of a new French-speaking dynasty.3 The raid on Cumbreland by the Northumbrian earl Gospatric, an event discussed in the previous chapter, came four years after William’s victory. By then, Cumbreland – the land of the Strathclyde Britons – had already been conquered by the Scottish king Máel Coluim. South of the Solway, Strathclyde’s southern provinces – described in the earlier Gospatric’s charter as ‘lands that were Cumbrian’ – had probably been in English hands since Siward’s time and must have lain outside the area conquered by Máel Coluim between 1058 and 1070.

William’s grip on the English throne was hindered by unrest stirred up by rival claimants, the most persistent of these being Edgar the Aetheling, a great-grandson of Aethelred the Unready. Edgar’s allies included his brother-in-law Máel Coluim of Alba, King Sweyn II of Denmark and various members of the English aristocracy. A series of revolts by Edgar’s supporters in Northumbria eventually prompted William to launch a campaign of devastation, the so-called ‘Harrying of the North’, in the winter of 1069–70. In the ensuing years, the Normans tightened their grip on northern England by building castles and establishing new lordships.4 By consolidating their power in lands close to the Scottish border they seem to have unsettled Máel Coluim who, in 1091, crossed the River Tweed to invade Northumbria. He laid siege to Durham but withdrew in the face of a Norman counter-offensive and eventually agreed a peace treaty with William Rufus, the son and heir of William of Normandy.5 In the following year, William Rufus came north with an army, his objective being to seize the old Roman city of Carlisle. The expedition was described in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

In this year King William with a great army went north to Carlisle and restored the town and built the castle; and drove out Dolfin, who ruled the land there before. And he garrisoned the castle with his vassals; and thereafter came south hither and sent thither a great multitude of peasants with women and cattle, there to dwell and till the land.6

Basing their ideas on an assumption that the district around Carlisle was the part of Cumbreland conquered by Máel Coluim before 1070 and raided by Earl Gospatric in that year, some historians see Dolfin as a subject of the Scottish king.7 There is, in fact, no warrant for believing that Carlisle and its environs or any territory south of the Solway lay under Scottish rule in 1092, or that these erstwhile Cumbrian lands were ever conquered by Máel Coluim.8 It is more likely that Dolfin was a rebellious Northumbrian lord who stubbornly refused to submit to William Rufus. His authority in the Carlisle district, like Gospatric’s in Allerdale, had probably originated in Earl Siward’s takeover of the ‘lands that were Cumbrian’. Dolfin may have been the son or grandson of a Northumbrian nobleman to whom Siward had granted a unit of lordship formerly held by a Strathclyder. It has been suggested that he was the son of Gospatric of Bamburgh – the earl who raided Cumbreland in 1070 – but this is just a guess based on the fact that Gospatric did have a son of this name who fits the chronological context. Alternatively, Dolfin of Carlisle may have belonged to the family of an earlier Dolfin who is known to have fought and died in Siward’s campaign against Macbethad in 1054.9

Norman control of the Carlisle area was strengthened by the granting of estates to new landowners whose names were of Continental origin. By the early 1100s, during the reign of King Henry I in England, a number of Anglo-Scandinavian -by place-names had become associated with this new elite. Examples include Botcherby and Rickerby which were granted, respectively, to Bochard and Richard – men with French names – who were responsible for maintaining two gates in Carlisle’s city walls (Botchergate and Rickergate).10 In Henry’s time, the area known as the ‘land of Carlisle’ encompassed not only the city and its hinterland but also other lands as far west as Allerdale and as far south as Appleby. Henry granted this entire region to a powerful Norman nobleman, Ranulf le Meschin, who made his mark by establishing two baronies centred on Burgh by Sands on the Solway coast and at Liddel Strength on the Scottish border.11 To each of these baronies Ranulf appointed one of his own henchmen. He seems to have tried to impose his brother William on an older barony at Gilsland, east of Carlisle, but failed to dislodge its incumbent lord. The latter was Gille, son of Boite, a mysterious figure of whom little is known. In 1120, Ranulf became Earl of Chester and returned the ‘land of Carlisle’ to direct royal control. King Henry then enlarged the area with the addition of the parish of Alston before splitting it into two sheriffdoms or ‘shires’ separated by the River Eamont. The northern shire was centred on Carlisle and was known as Chaerlolium, taking its name from the city. The southern shire was called Westmarieland, ‘the land west of the moors’, with an administrative centre at Appleby.12 New baronies were created within the bounds of Chaerlolium and, in 1133, a bishopric was established at Carlisle. After Henry died in 1135 his nephew Stephen became king of England and a volatile period followed the accession. Stephen’s hold on the crown was later contested by Henry’s daughter Matilda in a bitter civil war but the first major crisis of his reign was an invasion by the Scottish king David I, one of the sons of Máel Coluim, in late December 1135. David seized Carlisle and much adjacent territory and managed to hold onto these gains under the terms of a peace treaty negotiated with Stephen.13 David’s son, Prince Henry, was made earl of Carlisle and David himself died there in 1153. Four years after David’s death, his grandson King Máel Coluim IV was forced to relinquish the new earldom to Henry II of England.14 It was during Henry’s long reign (1133–87) that the shire of Chaerlolium became known as the county of Cumberland, being first recorded under this name in 1177.15

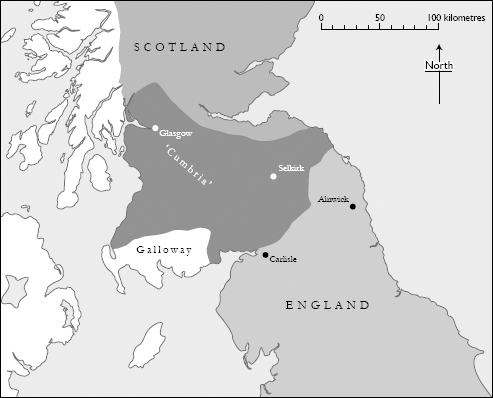

The prince of the Cumbrians

The Scottish king Máel Coluim, conqueror of Strathclyde, died in 1093 in a battle against Anglo-Norman forces at Alnwick. His death sparked a power-struggle which eventually brought his son Edgar to the throne. Edgar’s designated heir was his brother, Alexander, to whom he gave an earldom in lands north of the River Forth. To David, his youngest brother, Edgar allocated a substantial territory south of the Forth–Clyde isthmus, intending that David should take control of it when Alexander succeeded to the Scottish throne.16 At that time, however, David was based in England, having fled there with his brothers in 1093 after their uncle Domnall Bán had seized the throne in the wake of their father’s death. David remained in England long after Edgar and Alexander returned home. He became close to the court of Henry I, his brother-in-law, and was regarded as a prominent member of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy. When Edgar died in 1107, Alexander succeeded him as king but was reluctant to honour his bequest to their younger sibling, perhaps fearing that the wealth of a large lordship in the southern part of the kingdom might give David too much power.17 David was probably in no position to demand his inheritance at that time, for his patron Henry I was embroiled in a long-running war in Normandy which dragged on until 1113. With Henry’s attention distracted by the war, David would have had little hope of backing up any demands he might make on his brother. Moreover, David himself was part of Henry’s entourage and would have been obliged to take part in the Normandy campaign.18 It is possible that he had to wait six years before being in a position to claim the lands bequeathed to him by Edgar. By then, Henry was able to support the claim by threatening to invade Alexander’s kingdom if it was refused. Alexander was left with little choice, so David came home to take his inheritance. Edgar’s generous bequest placed David in control of a very large domain which he ruled as an autonomous province within the Scottish realm.19 He was not given one of the usual titles, such as earl, but was known instead as princeps Cumbrensis, ‘prince of the Cumbrians’ and Cumbrensis regionis princeps, ‘prince of the Cumbrian kingdom’. The lands under his control comprised much of what is now south-west Scotland, from Loch Lomond to the Solway Firth, with the exception of Galloway and some other territories. What his elder brother had in fact bequeathed to him was the former heartland of Strathclyde.

David’s principality stretched along the River Tweed from its source in the hills of Dumfriesshire to Teviotdale. Other parts of Tweeddale further east also lay within his domain but his authority was more limited there because Alexander ruled more directly. To the south-west, David’s domain bordered the ‘land of Carlisle’ which was then part of England. This region, although once ruled by the kings of Strathclyde, was not part of David’s inheritance. The exclusion of this erstwhile Cumbrian territory south of the Solway Firth was mentioned in one of his charters, where a scribe observed that he ‘was not, in truth, lord of the whole Cumbrian kingdom’.20 What David did have in common with the Cumbrian kings of old was a long frontier with the English. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, this border had frequently been crossed by armies intent on plunder or conquest. In the early twelfth century it may have been somewhat less volatile, for Henry I knew that his Scottish friend David now controlled the northern side.21 The bond between the two men, already strengthened by Henry’s marriage to David’s sister, was now reinforced by David’s own marriage to Matilda de Senlis, a wealthy Anglo-Norman widow who happened to be Henry’s second cousin. As a granddaughter of Earl Siward by his son Waltheof, Matilda had a family connection which gave David a potential advantage in future dealings with Northumbria. Through her, for instance, he could make a valid claim on the former Cumbrian lands south of the Solway, these having been part of the enlarged Northumbrian earldom held by Siward and Waltheof in the second half of the eleventh century. Although the earldom itself, as a formal rank or title, had been phased out in 1095 its territorial bounds were not forgotten.

David’s rule had a significant impact on what had once been the kingdom of Strathclyde. In 1113, soon after taking up his inheritance, he established a monastery at Selkirk in Tweeddale, granting it to monks of the Tironensian Order whose headquarters lay in France.22 The following year saw another ecclesiastical development: the revival of a bishopric at Glasgow in the heart of the old Cumbrian realm. This bishopric had evidently been defunct for a long time and was described in one contemporary text as ‘old but decayed’.23 The description suggests that the last Cumbrian bishop had been ousted during the Scottish conquest in the previous century and had followed his royal patrons into oblivion. In resurrecting the bishopric, David claimed to be restoring spiritual and moral guidance to the inhabitants of his principality. While such pious intentions might indeed have played a role, they were undoubtedly accompanied by political motives. The revived bishopric strengthened David’s hold on the Cumbrian lands by creating a spiritual authority which mirrored and supported his secular rule.24 He had good reason to consolidate his position in this way for, although he had the favour of the English king, he had less influence at the Scottish court at that time and was not yet his brother’s designated heir.

David’s inquest

Reviving the defunct bishopric of Glasgow necessitated a survey of its former possessions. To gather this information, David commissioned an inquisitio or ‘inquest’ of ecclesiastical landholdings within his principality. The resulting document, compiled between 1117 and 1124, was essentially a survey of church property within the old kingdom of Strathclyde. Indeed, the bishops later made an explicit link between their diocese and the Cumbrian kingdom by promoting themselves as the legitimate successors of its royal dynasty.25 The geographical limits of the inquest are a useful indicator of the extent of the kingdom, with the exclusion of Renfrewshire and Ayrshire suggesting that these areas were not part of it at the time of the Scottish takeover.26 They may have been seized from the Cumbrians by a neighbouring power, perhaps the Gall-Gáidhil, during the kingdom’s final phase. However, the inclusion of both areas within David’s wider domain indicates that they were in Scottish hands when King Edgar created the bequest for his younger brother, so they had probably been annexed during or after Máel Coluim’s conquest of Strathclyde. Unsurprisingly, the inquest excludes any territory south of the Solway Firth, despite the likelihood that the authority of bishops on the Clyde had formerly extended to the River Eamont in the days of the Cumbrian kings. In the early twelfth century, the spiritual needs of this region were already being met by Anglo-Norman clerics whose secular lord was the king of England. David obviously regarded it as belonging to Henry I and therefore made no claim on it while Henry lived, perhaps because any such claim would have required him to give homage to Henry.27 The inquest also sheds light on dealings between Cumbrian and English clergy after the collapse of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria in the late ninth century. It identifies the monastery of Hoddom, an important Northumbrian religious house from the seventh century onwards, as a possession of the bishop of Glasgow and thus, by implication, as an ecclesiastical centre within Strathclyde. Hoddom’s fate in the Viking period is undocumented but archaeological evidence suggests continuity into the tenth century when the surrounding area was certainly under Cumbrian rule. In the inquest, Hoddom heads a list of places in Annandale which were probably its dependent churches at the time of the Scottish conquest in the eleventh century.28 Nowhere in the inquest is there any sense that an ethnically distinct Cumbrian population remained identifiable within David’s domain. This is consistent with the scant survival of Cumbric place-names in the core territory of the old kingdom. Even in Clydesdale such names are quite scarce, their rarity suggesting a major upheaval in which the Cumbric language was swiftly replaced by Gaelic.29 If any members of the Cumbrian aristocracy managed to retain their lands into the twelfth century they can only have done so by assimilating with the Scottish and Anglo-Norman lords to whom David now granted substantial estates between the firths of Clyde and Solway. If any residual Cumbric-speaking communities still existed in this region in the early 1100s, their days were undoubtedly numbered. Two or three generations had probably passed since the fall of Strathclyde and there was no longer any incentive for anyone to maintain the Cumbric language or a Cumbrian identity. All important matters were now conducted in Gaelic, the language of the Scottish royal family and of the new landholding elite. ‘Scottishness’ therefore replaced ‘Britishness’ as the preferred cultural affiliation for people of ambition and was eventually adopted by everyone. There is thus no need to regard a contingent of Cumbrenses who fought in the Scottish army in 1138 as a remnant of the Britons.30 These soldiers may have been Englishmen from the part of ‘Cumberland’ around Carlisle, marching under David’s banner after his seizure of the city three years earlier. Nor should we take at face value the statement, made by an English archbishop of Canterbury in 1119, that the Glasgow diocese was served by a ‘bishop of the Britons’. While this shows awareness of the former existence of the kingdom of Strathclyde, it does not imply that anyone living within the new Scottish diocese still spoke Cumbric or maintained a Cumbrian identity.31

MAP 18 David’s principality: ‘Cumbria’ in the Scottish kingdom, c.1120

The Cumbrian legacy

Cumberland, the English county, continued in existence until a major reorganisation of local government in the United Kingdom in 1974. Since then, together with neighbouring Westmorland, it has been subsumed within the larger county of Cumbria. Both the older name and the new are found in medieval texts as synonyms for the kingdom of Strathclyde. Ironically, neither is preserved in the landscape of Clydesdale, the core of the kingdom, nor is there a general awareness that this was once the very heart of ‘Cumbrian’ territory. There are, of course, a number of place-names of Cumbric origin around Glasgow and in other parts of south-west Scotland, each a reminder of the language spoken in these districts a thousand years ago, but place-names commemorating the Cumbrians themselves are rare. The most familiar is probably ‘The Cumbraes’, a collective name for a pair of islands off the coast of North Ayrshire, which derives from Old Norse Kumreyiar (‘isles of the Cumbrians’).32 Cumbernauld in North Lanarkshire and Cummertrees in Dumfriesshire seem, at first glance, to have names derived from Old English Cumber (‘Cumbrian’ in the sense of ‘North Briton’) but the first element in both names is more likely to mean ‘confluence’ (Gaelic comar and the Cumbric equivalent of Welsh cymer respectively).33 To find Old English Cumber in place-names we must look across the Solway Firth to the lands around Carlisle. Here, the Cumbric-speaking settlers of the tenth century are still remembered by the continuing use of ‘Cumbrians’ to describe the inhabitants of the post-1974 county. The term now encompasses not only the people of the former county of Cumberland but those who dwell in the erstwhile Westmorland south of the River Eamont, together with neighbouring communities in the Cartmel and Furness peninsulas that were formerly within Lancashire. Another reminder of the Viking Age survives on the southern outskirts of Carlisle, where the village of Cummersdale has a name in which Old English Cumber is attached to Old Norse dalr to denote ‘the valley of the Britons’.34

Although present-day Cumbrians are indistinguishable from folk in other parts of England, in terms of language and national identity, they maintain a sense of regional distinctiveness in which memories of the ancient kingdom play a role. The local legends of King Dunmail and Ewen Caesarius have already been mentioned, but other links with the distant past might also be preserved. One possible ‘survival’ is a system of counting which uses numbers that appear to derive from a Brittonic language. In the nineteenth century, when it was first documented, this was used as a method for counting sheep in the Lake District and in other parts of the old counties of Cumberland and Westmorland. Observers noted that the numbers or ‘scores’ were not only used by shepherds but were also found in children’s rhyming games. Certain linguistic similarities with Welsh and Cornish numerical systems were identified and the idea of a connection with the ancient past soon arose. In truth, the situation is rather more complex. Variant forms of the counting system have been found in other parts of northern England – both east and west of the Pennines – and also in Scotland, with a few examples from southern England. Nonetheless, although their precise history is unknown, the numbers have been seen as originating in northern Britain in areas where the Cumbric language was once spoken. This might turn out to be the best explanation, in spite of a more sceptical idea that they were brought to English and Scottish sheep-farming districts by itinerant shepherds from Wales. How and why such a counting system would have survived the otherwise complete disappearance of Cumbric speech are questions that remain unanswered.

Sheep-counting in Cumbric?

The numbers in the left-hand column below were recorded in the Lake District valley of Borrowdale in the nineteenth century.

Modern Welsh

| 1 = yan | 1 = un |

| 2 = tyan | 2 = dau |

| 3 = tethera | 3 = tri |

| 4 = methera | 4 = pedwar |

| 5 = pimp | 5 = pump |

| 6 = sethera | 6 = chwech |

| 7 = lethera | 7 = saith |

| 8 = hevera | 8 = wyth |

| 9 = devera | 9 = naw |

| 10 = dick | 10 = deg |