CHAPTER 2

How a Noble Sales Purpose (NSP) Changes Your Brain

Great minds have purpose, others have wishes.

—Washington Irving, short‐story writer

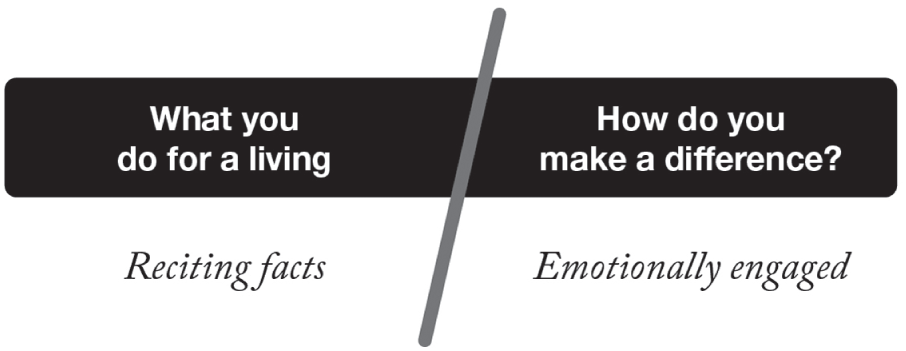

Imagine you're at a neighborhood party or standing on the sidelines of a kid's soccer game. You engage in a conversation with the person next to you, and he asks the age‐old question: “What do you do for a living?”

How do you answer? You've likely been asked the question a hundred times, so you probably have a standard job description‐type answer. If you're alone right now, say it out loud. If you're reading this book on a plane or in a coffee shop, just mumble your answer under your breath.

Pay attention to how you feel saying those words.

If you're like most people, you probably give a fairly rote response that doesn't require much thinking: something along the lines of, “I sell software” or “I'm regional manager for XYZ Company.” If you work for an impressive firm or you have an impressive title, you may have said, “I run a sales team for Google” or “I'm the VP of Sales at Clorox.” But it's usually still a pretty standard answer.

Again, remember how it feels to say those words out loud. This is your baseline.

Now, to give you an understanding of what Noble Purpose does to your mind, we're going to go a bit deeper.

I'd like you to think about a time when you made a difference to another person at work. Perhaps you helped someone on your team, did something great for a customer, or lent an ear when a colleague needed to talk. It may have happened in your current job, or it may have been in a past job. Either one is fine.

- What was the situation?

- How did you make a difference?

- What did the other person say?

- How did he or she look?

- How did you feel afterward?

Imagine yourself telling this story out loud. In fact, if you have a colleague or friend nearby, tell them your story.

Compare how you felt in the first scenario, when you described what you did for a living, with how you felt in the second scenario, where you told a story about making a difference.

What do you notice?

How was the second time different from the first time? Which one did you enjoy talking about more? Which one was more engaging? Which one makes you prouder? And here's the key question: which story would you rather listen to if you were on the other end?

Most people experience a pretty dramatic shift when they move from function‐based conversation to a more purposeful “make a difference” conversation.

When I pose these questions in keynotes, I ask people: “Tell the person next to you what you do for a living.” The room is a low‐level buzz. Then, when you ask people to describe a time you made a difference to another person at work, the whole room lights up. The physical and emotional difference between the two scenarios is startling. When I ask groups to compare them, I hear things like:

“The first time was a no‐brainer, but the second time I was totally into it.”

“The first time was boring; the second time was more emotional.”

“I was on autopilot the first time, but the second time it was like I was reliving the experience again.”

“The first time I thought it; the second time I felt it.”

That's a fairly accurate description of what happens to your brain. The first time—when you describe your job—you're using your brain at a very basic level, almost on autopilot. The second time, when you describe making a difference, you ignite your frontal lobe. This is the part of the brain associated with reasoning, planning, problem‐solving, language, and higher‐level emotions such as empathy and altruism.

Describing the meaningful impact you had on another person engages a higher‐level part of your brain than when you describe your job function. Here's what I observe when people do this exercise: When people talk about what their basic job function, they:

- Smile politely

- Use rote language, such as reseller, provider, end‐to‐end solutions, implement, and so on

- Sit relatively still

And their listeners nod nicely.

When people describe making a difference, they:

- Smile with their whole faces

- Use colorful details, such as describing the look on someone's face or the setting

- Become much more animated and describe the impact they had on someone

And their listeners lean in and ask questions.

People share the two experiences—what they do for a living versus making a difference—within five minutes of each other. When you stand on the stage, watching people respond, you'd think it was a completely different day. They look like an entirely different group of people.

The first time, it's just a regular crowd of businesspeople politely speaking to one another in low voices. The second time, volume cranks up. The people get engaged. They start laughing. Some people even stand up when they tell the second story. They can't help themselves.

There's more energy and enthusiasm in the air. When you watch them the second time, you'd think they'd just won the lottery or heard some great news. And in a way, they did. By describing how they made a difference to someone, they got the best payoff a human being can have: they were reminded of just how much their life matters.

These are the kind of powerful emotions that selling with Noble Purpose can ignite.

Customer Centricity Is Not Enough

A lot of organizations prioritize customer centricity. It sounds good in theory. Let's rally our organization around customer needs. Go team! But customer centricity as it's typically implemented is missing a crucial element: impact.

Meeting the customer's needs is certainly better than ignoring your customer's needs. But it can put your team in a reactive position, one that is no different from any of your competitors. If customers are telling you their needs, they're also telling your competition. Most customer‐centric strategies as they're practiced today rely on the unspoken assumption that the customer has the best and most accurate understanding of their needs. In many cases, this isn't true. As Henry Ford famously said, “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

It's not that sellers should be arrogant and ignore customers' needs. But they should have expertise that the customer does not. Exceptional sellers have insights into how customers can achieve their goals: insights customers may not have thought about.

Telling your team to simply focus on the customer could mean anything from helping the customer achieve their goals, to giving the customer a lower price. Without clarity about the impact the organization wants to have on customers, people can wind up feeling like indentured servants. Consider the difference between an organization that says, “Our goal is to meet our customer's every need,” versus an organization whose stated purpose is “We improve the way our customers do business.” Which organization feels more empowered? Trying to please the customer is nice, but it's hardly galvanizing, and it's rarely differentiated. When you have clarity about how you want to improve the customer, you create a more innovative organization.

When your people understand that we are here to improve our customer's lives and businesses in ways they may not have even known were possible, your team has a clear North Star. The customer is at the center of the business, but instead of merely reacting to customers, the team is proactive about helping customers get to an even better place.

The stakes become higher, and the role of everyone on the team becomes more important.

The Two Big Human Needs: Belonging and Significance

Once you get beyond basic needs like food and shelter, human beings have two core emotional needs: belonging and significance. We want to be connected to other people, and we want to know that what we're doing matters to someone. The need for belonging and significance transcends age, culture, sex, race, and socioeconomic status.

We don't just want to make a difference in our personal lives or through philanthropic activities. We want to make a difference at work. We spend the better part of our waking hours at work. Those hours ought to mean something. When you know that your job matters to people, you come alive. Your frontal lobes light up, and you have greater access to problem solving, language, and empathy.

Yet for some reason, many teams seem to operate as though some bizarre memo went out years ago saying, “Please don't bring any emotions to work.” This mentality is entirely unhelpful. When was the last time you heard a CEO say, “I wish my people weren't so motivated and excited”? Any good leader knows, achieving peak performance requires emotional buy‐in. The reasons people resist addressing emotion at work is because:

- Emotions are messy and hard to understand. When you bring in the good emotions, you're also going to have to deal with negatives. This can feel like Pandora's box; people resist opening it.

- People aren't skilled at dealing with other people's emotions. Even the silent, stoic boss is generating an emotional response from his or her team. It may not be acknowledged, but it's there. It feels safer to back away from other people's emotions rather than owning the role you may play in creating them.

- We delude ourselves into believing our business decisions are logical. One look inside any merger or acquisition will tell you that emotion plays a role in every business decision. Logic makes you think; emotion makes you act.

Ignoring the emotional element doesn't make it go away; it simply prevents you from leveraging it. When we acknowledge the role emotions play, we can learn to tap into them for good. If you want to create a highly engaged team, you can start by strengthening their emotional connection to their work.

You read in the introduction about a top‐performing biotech salesperson who outsold every other rep in the entire country three years running. She achieved this because every day when she went on calls, she remembered a grandmother she had helped. Thinking about the grandmother did more than just motivate this sales rep to make extra sales calls on a rainy Friday afternoon. It ignited her frontal lobe, which made her a better problem‐solver and strategic planner, more skilled with language, and more empathetic with her customers.

Is it any wonder that she was the number‐one rep three years running? Her peers and competitors were likely conducting sales calls with the basic parts of their brain, going through the motions mechanically without igniting any kind of purpose in themselves or their customers.

But because the top rep was thinking about the person she had helped—the grandmother who, because of her product, could now play with her grandkids—she was leveraging both her intellect and her emotions to their fullest extent.

A Noble Sales Purpose ignites that type of higher‐level thinking with everyone on your team. It serves as an organizing element for your sales force and keeps you focused on the big picture. It's your version of the grandmother.

Sellers who carry a clear picture of the impact they want to have on customers in sales calls are more powerful. They're more creative, they're higher energy, and they're more resilient in the face of setbacks. Your job as a leader is to proactively help them generate that mental picture and keep it alive on a daily basis.

An NSP answers three questions for your team:

- What impact do you and your company have on customers?

- How are you different from the competition?

- On your best day, what do you love about your job?

An NSP is not “We're going to be the number one provider of end‐to‐end solutions.” That's your goal, but it doesn't speak to how you make a difference in clients' lives. An NSP isn't about your desired position in the market. It's about how you impact your clients today.

A 10‐Degree Shift Can Change Your Direction

Imagine you're sitting in a jet parked on a runway. If you alter your direction 10 degrees north, you wind up at a totally different destination. This is how just a small shift at the start of the journey puts you on an entirely new trajectory.

Establishing your NSP is the seemingly small shift on the runway that takes you to a more exciting destination. You may already have a clear purpose statement, or your NSP may be found inside your existing mission and vision. Or you may be starting from scratch. Whatever the case, as you read this section, notice how these organizations use their NSP as a starting point to create competitive differentiation, ignite emotional engagement, and drive revenue growth.

The following are examples of organizations driving exceptional results by using an NSP. Keep in mind as you read these examples that crafting your NSP is the start of the process.

Atlantic Capital Bank: From Transactional Banking to Fueling Prosperity

Atlantic Capital Bank (ACB) is an Atlanta‐based commercial bank founded in 2007 with approximately $3 billion in assets. CEO Doug Williams and his team founded ACB to create an exceptional bank. In an industry mired in negative press, they wanted to establish themselves as honest bankers who truly care about customers. Yet after a decade of solid growth, they found themselves becoming just like other banks.

In the day‐to‐day drumbeat of the financial industry, it's challenging to keep the focus on client impact. With pressure to hit financial metrics, the numbers can often become the only story anyone talks about. But Williams knew a numbers‐only story is a recipe for a transactional relationship with clients and becoming a commoditized brand. He wanted to differentiate.

When we interviewed teammates, managers, customers, and the executive team to uncover ACB's points of competitive differentiation, we discovered that others shared Williams' sentiment. Working with the executive team, we crafted ACB's Noble Purpose: We fuel prosperity.

In an industry where other banks talk about building personal wealth, ACB chose prosperity because they wanted to communicate a shared commitment to a more holistic ideal.

The executive leadership team got specific about how their purpose drives strategy. We created purpose maps articulating ACB's Noble Purpose, target customers, points of differentiation, and leading indicators of success. For every employee, the story was clear: we are the team who fuels prosperity.

The activation plan included personal messages from Williams, leadership coaching, and integrating ACB's Noble Purpose into recruiting, hiring, onboarding, marketing, and sales behavior. A critical element of the rollout was training the sales team and the sales managers. Instead of the traditional product‐focused approach, the team learned how to connect with clients in a deeper, more meaningful way. ACB cofounder and Executive VP Kurt Shreiner says, “We changed the way our people think. You focus on the client and helping them achieve their dreams, versus I'm going to sell another product. Our internal and external conversations are entirely different.”

In a matter of months, the culture shifted. The team became more engaged. Fueling prosperity was at the core of customer conversations, decision‐making, and daily operations.

A year after launching their Noble Purpose initiative, ACB's year‐over‐year continued operations before-tax income increased by 81%. Williams and his team say there's a new energy in the air. Clarity about ACB's purpose enabled the executive team to make a smart divesture without belaboring the process. Backstage teams are more customer‐oriented, and bankers are proactively pursuing new clients.

In 2019 ACB was voted a Best Place to Work in Atlanta, based on anonymous employee surveys. They were also chosen as one of the Best Banks in America by American Banker Magazine. As mentioned earlier, Williams was featured on the cover of American Banker with a story describing his team's dramatic transformation.

Supportworks: Redefining the Home Contracting Industry

Attracting and keeping top talent is a business imperative. It's even more challenging when you're hiring blue‐collar workers, in the middle of Nebraska, to muck out people's basements.

Supportworks (and their sister company, Thrasher) is an Omaha‐based concrete and foundation repair firm that wanted to establish competitive differentiation for their brand in a bigger, bolder way. Their products aren't sexy, but they're the best in the business. The leadership team needed to help their national network of dealers break out of the price trap that is so common in the home service industry.

In our first session, the leadership team talked about how the contracting industry had a bad reputation. When you call a contractor, you never know whether they're going to show up or not. Pricing is often sketchy. Contracting firms are also notoriously poor employers.

Supportworks wanted to change that. They wanted to redefine the home contracting industry for the better. They wanted to set a new standard for how customers are treated in the industry. We landed on their Noble Purpose: We redefine our industry.

Supportworks decided they were going to be the company that changed the frame for what customers expect, and the company wanted to become a destination employer in the process.

Because they sell through dealers, Supportworks couldn't mandate a top‐down approach. They had to get their dealers excited about implementing the Noble Purpose with their own teams. We created a plan to help dealers link each employee's job to the greater purpose of the business, and gave them tools to establish differentiation in their markets.

Convincing a rough and tough crew of predominately male leaders to talk about purpose and praise their teams was no small task. We knew the connection between purpose and recognition had to be accessible, be easy, and not require a long speech. Supportworks created Purpose Citations: peel‐off pads for managers in the field to give quick positive feedback about how employees were living their purpose. Managers could check off things like “enviable smarts” or “contagious do‐goodery.”

As of this writing, Supportworks' purpose training is lauded as some of the most differentiated training in the contracting world.

Supportworks has also become a destination employer. They've been voted a Best Place to Work multiple times. Employee engagement has soared. Revenue has exploded as they've added dealers across the country who want to become part of their movement. Their team will tell you, Supportworks is unstoppable.

CMIT Solutions: From Techies to Trusted Advisors

CMIT Solutions is a franchise organization that provides managed IT services for small businesses. When CEO Jeff Connally took over the business in 2006, he began to shift the team from hourly billing to a managed services, fixed‐fee model.

Most of CMIT's franchisees have a technical background. They were used to being on call and billing their time for client requests. Few of them had any sales experience.

When asked to describe themselves, they typically say, “We provide IT service.” Yet our interviews with their most successful franchisees revealed that CMIT does much more than simply provide IT services. The best franchisees were advisors to their clients; advisors who alleviate and prevent some of the biggest headaches in business: system problems. Their team landed on an NSP that reflected their aspirations for their customers: We help make small businesses more successful.

Connally says, “When we went from ‘We sell IT services’ to ‘We help make small businesses more successful,’ it changed everything. That seemingly simple reframe pointed our team in an entirely new direction. Now our guys feel like the white knights of the IT world. They're going after new business with a zeal they never had before.”

CMIT launched their Noble Purpose during the recession. Despite a tough economy where clients were cutting back on outside vendors, they grew sales by 35% the first year. Changing their focus from the services they provide to the impact they have on clients created a shift in the way their team approaches customers. Connally says, “Our people are technical, so their tendency is to jump right into the tech stuff. Now, instead of [taking that approach], we take a step back and address the situation from a business perspective.”

He continues, “We pulled our NSP to the front and center of everything we do. It helped move our franchisees from simply being IT providers into a trusted advisor/partnership role.”

Post‐recession, CMIT held fast to their NSP, using it to drive exponential revenue growth. In a world where organizations aspire to increase earnings by 10x, CMIT's earnings have increased by a multiple of 36x. They're driving outsize earning because they're attracting and holding on to the right franchisees.

CMIT's franchise churn rate has gone from 39% when they launched their NSP to below 4%—an almost unheard‐of number in the franchise world, where anything below 12% is considered very good. The team went from selling franchises to awarding them. They've now become the largest managed services provider in the mid‐market space.

G Adventures: Igniting Passion and Purpose in Resellers

Make no mistake, G Adventures is a sexy company (no offense, banking, basements, and IT). As the global leader in adventure travel, they take people everywhere from African safaris to cycling in Tuscany to trekking the Inca Trail. Their team is committed to changing lives through travel. The company had experienced 20% year‐over‐year sales growth for over two decades.

Yet as exciting as G Adventures is, they needed to translate their passion to their resellers: travel agents who book trips for their clients. The sales team knew their trips were life‐changing, but the travel agents often saw G Adventures as just another vendor.

To help you understand the business model, many travelers still turn to travel agents for advice about where to go and for help with complex trips. Agents direct a large number of travel decisions and dollars. Because of this, every tour company, hotel, and travel vendor on the planet wants agents to love them. The agents themselves typically join the industry because they are passionate about travel. Yet as they progress in their careers, agents often find themselves booking dream trips for others while they sit at their desks.

The sales team at G Adventures wanted to do more than sell trips: they wanted to help their agents rediscover their own sense of purpose. They landed on their NSP: We help people discover more passion, purpose, and happiness.

In this case, “people” extended to agents. This required transforming the sales process. Instead of showing agents photos and videos of trips, the team created interactive sales experiences. They used everything from inspirational card decks and music to an actual magic trick to help their agents, people sitting at their desks, reconnect to the power of changing lives through travel.

The sales team even went so far as to change their job titles from account executives to Global Purpose Specialist, or GPS for short. They wanted to make it clear that their job is to help agents discover more passion, purpose, and happiness in their jobs, so they can help people discover more passion, purpose, and happiness on trips.

G Adventures' impressive year‐over‐year 20% sales growth has now become 35% growth. Their annual event, the Change Makers Summit—held for the agents who change the most lives—has garnered international recognition as one of the most innovative events in the industry.

Orange County Court: Simple Elegance

Many companies tend to try to “kitchen sink” their NSP—that is, to throw in every single thing you could possibly do for customers. It's important to fight the temptation to overdescribe; a simple statement is much more powerful.

One of my favorite examples of simple elegance comes from California's Orange County Court system. Their NSP is: We unclog the wheels of justice.

You might not think of a court system as having customers, but the Orange County Court believes they do. They consider the plaintiffs, the defendants, the jurors, and the lawyers all their customers. Their NSP speaks to their desire to make a difference in people's lives during times of conflict and stress. They strive to implement the principles of our country in a just, fair, and efficient way for all parties involved.

Interestingly, Orange County's NSP didn't come down from the executive team. It came from a single person. During a leadership program, the 60 top managers, divided among 8 tables, discussed how Orange County makes a difference to customers. When the teams reported back their results, one of the in‐house attorneys stared at the lists on the flip charts and said, “You know what we do? We unclog the wheels of justice.”

You could have heard a pin drop in that room after she said it. Sixty people sat taller in their chairs, smiling because they knew their jobs mattered. I swear that I even saw some of them start to get misty‐eyed.

These words spoke to the highest aspirations of everyone in the room. That single powerful statement contained what Jim Collins refers to in his book Good to Great as “the quiet ping of truth like a single, clear, perfectly struck note hanging in the air in the hushed silence of a full auditorium at the end of a quiet movement of a Mozart piano concerto.”

An ideal NSP is not full of bravado or bluster; it's not something you hope to do. It's something you can do right now. It's fully within your grasp, and every person in the room knows it. It doesn't require explaining or defending, because it taps into what you're already doing and what you want to do more of. Your NSP names who you are on your best day as an organization.

You Don't Have to Create World Peace

You'll notice that none of the preceding examples include discovering lifesaving new drugs or creating world peace. They come from five very different organizations in industries whose products (commercial banking, foundation repair, IT support, travel, and court services) don't always scream “Noble Purpose.”

I intentionally chose these organizations to demonstrate how seemingly ordinary companies are harnessing the power of purpose. These examples demonstrate that no matter what you sell, you can always find your NSP.

You might also notice that when we talk about these firms, we don't use impersonal pronouns. Instead of saying “The company uses its NSP to differentiate,” we say “The company uses their NSP to differentiate.” Our words create worlds. Referring your company as an “it” is as impersonal as referring to customers as its. The best teams don't talk about the company and the customers; they talk about our company and our customers.

Why Mission and Vision Aren't Enough

Mission and vision statements can be compelling. But more often than not, they're internally focused. In Grow: How Ideals Power Growth and Profit at the World's Great Companies, former Procter & Gamble (P&G) CMO Jim Stengel writes, “When you strip away the platitudes from those documents, what's left typically boils down to: ‘We want our current business model to make or keep us the leader of our current pack of competitors in current and immediately foreseeable market conditions.’”

In today's more socially aware times, mission and vision have expanded to include other stakeholders. Yet many don't amount to much more than: we want to serve our customers, our employees, and our communities, make as much money as possible, and be nice people while we're doing it.

This is the blah blah blah formula for mediocrity.

Even the largest organizations benefit from a succinct purpose. I was a sales manager for P&G early in my career. During my tenure, I saw our stock rise and split, delivering a 199% return. But by 2000, P&G was in trouble. The company lost $85 billion in market capitalization in only six months. Jim Stengel says, “P&G's core businesses were stagnating and its people were demoralized.”

Great brands weren't enough. P&G's people needed a purpose.

A.G. Lafley, then the CEO, asked Stengel to take on the role of global marketing officer to help transform the culture of the company to one wherein “the consumer is boss.”

Stengel says, “To hit these big targets, we needed an even bigger goal: identifying and activating a distinctive ideal, a purpose. Improving people's lives would be the explicit goal of every business in the P&G portfolio.”

Stengel writes, “A.G. Lafley and I—along with the rest of the senior management team—expected each business leader to articulate how each brand's individual identity furthered P&G's overarching mantra of improving people's lives. We also had to model the ideal ourselves. And we had to measure all our activities and people in terms of the ideals of our brands and the company as a whole. The success of that effort brought P&G's extraordinary growth from 2001 on.”

Notice, each one of the brands had to clarify its alignment toward the purpose. Identifying a larger purpose put P&G back on course. The 175‐year‐old consumer giant remains one of the most admired companies in the world. The company's story demonstrates that no matter how big you are or how long you've been in business, you can always reclaim your Noble Purpose.

Southwest Airlines is another commonly cited example of a company founded on a Noble Purpose. Since you've already seen how Noble Purpose is being used by several less‐high‐profile firms, I'll use Southwest here to illustrate the difference between mission, vision, and purpose. Roy Spence, who worked with Southwest on their purpose in the early days, explains in his book, It's Not What You Sell, It's What You Stand For:

- Purpose is the difference you're trying to make.

- Mission is how you do it.

- Vision is how you see the world after you've done your purpose and mission.

He illustrates how it works at Southwest:

- Purpose: “Southwest Airlines is democratizing the skies.”

- Mission: “We democratize the skies by keeping our fares low and spirits high.”

- Vision: “I see a world in which everyone in America has the chance to go and see and do things they've never dreamed of—where everyone has the ability to fly.”

Their purpose, democratize the skies, trumps everything. It doesn't make Southwest immune from market pressure or potential hazards in the high-stakes, high‐risk game of air travel. What their purpose does do is point their team and act as a lens for decision‐making. If your mission and vision are vague, or you don't have them, don't worry. The right purpose is the most important thing for pointing your team.

Spence tells a famous story from several years ago. Consultants came into Southwest and said that if they started charging for bags, they would immediately add $350 million to the bottom line. “All the other airlines are doing it,” the consultants said. Southwest could make a fast profit if they did the same.

Senior leaders Dave Ridley, Gary Kelly, and others said, “No, that violates the purpose of our company,” and instructed the team to “go find the money.” Charging for bags wouldn't give more people the chance to fly; in fact, it would make the skies less accessible.

“But you'll make more money,” said the consultants and finance team. The answer was still, “No. It doesn't serve our purpose.” Ultimately, Southwest's refusal to stray from their purpose made them money instead of costing them money. Southwest launched an ad campaign called “Bags fly free.” Nine months later, the financial team reported the results. By running the ad campaign and sticking to their purpose, Southwest drove $1 billion in new revenue, taking additional share from their competitors.

Preventing Your Personal Wells Fargo

The primary purpose of an NSP is to create competitive differentiation and emotional engagement, and to give you a North Star during times of challenge and uncertainty. Having said that, an NSP can also keep you safe from costly mistakes and ethical lapses. Your NSP keeps your team from going down a rabbit hole of unethical behavior simply to hit their numbers.

The Harvard Business Review 2019 issue's lead article, “Are Metrics Undermining Your Business?,” describes a problem the authors refer to as strategy surrogation. Surrogation occurs when the metric of a strategy replaces the strategy itself.

Using Well Fargo to illustrate, authors Michael Harris and Bill Taylor describe how employees at Wells Fargo opened 3.5 million deposit and credit card accounts without customers' consent in an effort to implement its now‐famous cross‐selling strategy. CEO John Stumpf frequently told his team, and the press, cross‐selling is the centerpiece of Wells Fargo's strategy.

To be fair, sometimes Stumpf added that cross‐selling was the result of serving customers well. But Wells Fargo didn't spotlight daily measurements of how well they served customers. Instead, they measured and rewarded cross‐selling. In effect, the metric became the strategy. And we all know how that turned out.

The HBR piece says, “The costs from that debacle were enormous and the bank has yet to see the end of the financial carnage. In addition to paying fines ($85 million) reimbursing customers for fees ($6.1 million) and eventually settling a class action lawsuit to cover damages as far back as 2002 ($142 million).” The authors note, “Wells Fargo faces strong headwinds in attracting new customers.” The reputational damage will follow the company for at least a decade, and probably closer to a generation.

Surrogation: When the Metric of the Strategy Takes the Place of the Strategy

While Wells Fargo may be the current poster child for bad behavior, they're hardly the first firm to focus on the metric instead of the strategy or to look inward, at objectives, versus outward, at customer impact. That's why you want to make your NSP—the impact you have on clients—as clear and present as you do your sales targets.

Surrogation occurs in even the most well‐intentioned organizations because client impact is hardier to codify than sales numbers. Leadership authentically proclaims, “We want to be customer‐driven.” But when they try to find a way to measure the success of their strategy, it's easier to double down on a single indicator, like cross‐selling.

Organizations driven by a Noble Purpose measure cross‐selling and other typical revenue‐driven metrics. But they use a multitude of additional metrics. They assess leading indicators—which tend to be more qualitative—rather than relying solely on sales numbers, which are more quantitative lagging indicators.

For example, Atlantic Capital Bank, which you read about earlier, measures the number of referrals they get from clients. Rich Oglesby, President of the Atlanta division, says, “It's an imperfect number, but it tells us how well we're delivering on our Noble Purpose—we fuel prosperity.” The team does not get individual bonuses on the number, so there's no incentive to cheat or say you got a referral when you didn't or steal someone else's referrals. Instead, the team tracks referrals and celebrates them as a metric of how they're performing in live time as a team.

Revenue is a lagging indicator: it tells you how well you did in the past. Client referrals are a more leading indicator. They tell you what clients are experiencing with your organization right now. When they love doing business with you, your clients become your best ambassadors. Part of a purpose‐driven strategy is to identify the leading indicators that tell you how you're doing with clients today. These vary by industry and organization. Once you're clear about your NSP—the impact you want to have on customers—it's easier to find the metrics that will measure your progress.

Business is a series of qualitative behaviors and beliefs that produce quantitative results.

The leadership opportunity is at the beginning of the process to shape the language and beliefs of the organization. Those are 100% within leadership's control. If you focus on the lagging quantitative indicators, the team will scurry around to hit them, but often at the expense of customer trust. As Doug Williams of ACB said earlier, while you may manage the back‐end numbers, you want to lead to the purpose, which is more qualitative.

Imagine if Wells Fargo had a NSP similar to Atlantic Capital Bank's. Picture their CEO telling the team, “Our purpose is fueling prosperity for our clients and our communities.” Envision a division leader saying, “If you're a banker, our purpose should be your North Star. All of our products should be designed with client prosperity in mind. When you speak with clients, find out what prosperity means to them, and then use our solutions to help them get there.”

If Wells Fargo leadership had articulated a Noble Purpose like that, and they had cascaded down through management, it's unlikely the company would have experienced the widespread problems it did. If an individual banker did create fake accounts, their colleagues probably would have reported it, because it was out of alignment with the stated organizational purpose.

John Stumpf initially claimed the Wells Fargo employees creating fake accounts were outliers. He tried to lay the blame on a few overly aggressive managers. But it didn't ring true. It didn't ring true for the market, or employees, or customers. Stumpf's much‐repeated directives about cross‐selling and his reputation for pressuring sales teams made it obvious that he may not have committed the crime, but his language and strategy laid the foundation for it to occur.

How NSP Drives Shareholder Value

Picture two firms in the software space. One is the leader in the employment market. The other is a software company that serves schools, foundations, and non‐profits.

The firm in the talent space was founded for the purpose of helping people find great jobs. They've driven exponential sales growth for over 20 years. They're a top‐performing tech stock, and their client engagement is high. Their new CEO has big plans to take the firm to an even higher level.

The other firm, which helps non‐profits connect with donors and improve contributions, is also the leader in their space. But unlike the first firm, they're not growing. Several of their flagship products have stagnated, and their team is having trouble differentiating themselves. Top performers are leaving, and morale in the sales team is low. This company also has a new CEO, who they hope will reinvigorate the team.

Which company do you think is most likely to improve stock price? The organization with highly engaged clients, who is clear about their purpose? Or the organization with lagging products and low engagement?

Both of these firms actually exist. The first firm is Monster.com, based in Boston. In the early 2000s, Monster was the top‐performing tech stock of the year and the market leader in the employment space. Monster was founded on the belief that everyone deserves a great job. The team was on fire to help people find better jobs. Then, after several years of stellar growth, the original founder and several of the early days' employees went on to new ventures. The new CEO, Sal Iannuzzi, arrived in 2007, and his challenge was to take the business to the next level. When you track the language in their public town halls and Iannuzzi's earnings calls, you can see a clear change.

The leadership team stopped talking about helping people find better jobs. Instead, their focus was on scaling and driving stock price. They went from a business focused on customer success to a business focused on itself. With no conversations about clients, innovation failed, and clients disengaged. After years of being the industry leader, Monster lost their mojo. Their revenue fell, earnings declined, the stock price tanked, the CEO was fired, and a company once worth billions was sold for pennies on the dollar. Ouch.

The other firm is Blackbaud, based in Charleston, SC. In 2014, when their products and stock price were lagging, they brought in Mike Gianoni as their new CEO. Gianoni came out of the financial services industry; he understood the product challenges and the business financials. But instead of focusing exclusively on the numbers, Gianoni did something different. He focused on the impact Blackbaud had on customers, who were schools, non‐profits, and foundations. He says, “When I first started at Blackbaud leaders would stand on stage and in a 1‐hour meeting they would spend 45 minutes on financials.” Gianoni flipped the model. He now spends only 5 minutes on financials. His new format is “What's our purpose, how does our work impact clients, are we being effective in serving them, and are we doing OK financially?”

President and General Manager of Blackbaud's Nonprofit Division Patrick Hodges says, “Most software companies want mercenaries, people who will just sell the heck out of your stuff. Instead, we continue to pull on our Noble Purpose.” The Blackbaud sales teams were trained to bring their purpose to the center of their sales efforts, and when they did, it was like unleashing the power of a thousand suns. Hodges, who was the VP of Sales for General Markets at the time, led the charge to amplify the purpose.

Since embracing their Noble Purpose in 2014, Blackbaud's customer base has grown 55%; recurring revenue has more than doubled and now comprises 90% of total revenues; the addressable market has increased by over $4 billion through acquisition and organic product builds; and the company has risen to one of the top 30 largest cloud software companies in the world. As of this writing, Blackbaud's stock price has more than doubled. Blackbaud was voted a best place to work. Gianoni was named one of the top 50 SaaS CEOs and named to Forbes' 2019 list of America's Most Innovative CEOs.

People often wonder if a concept like Noble Purpose can drive value in a quarterly capitalism‐driven stock market. The previous two stories demonstrate that not only does it drive value (Blackbaud), but the absence of a Noble Purpose also erodes value (Monster).

These two stories are not isolated incidences. They're a side‐by‐side comparison of what happens when leadership focuses on the money story versus the meaning story.

Noble Purpose is hardly the only thing Blackbaud got right. They adjusted their business model, they created new products, they hired the right people, and they made hundreds of decisions that drove their success. Their Noble Purpose served as a lens for making those decisions and became the force multiplier that propelled the company forward.

Shareholders vs. Stakeholders

Shareholders are not stakeholders. It's crucial that every leadership team recognize this. Shareholders don't make sales calls; they're not required to go the extra mile, and they don't interact with customers. Shareholders invest because they expect a return on their money. Passion is not a requirement for shareholders; it's a must for stakeholders. The stakeholders are the employees responsible for delivering shareholder value.

A strong NSP doesn't distract you from delivering shareholder value. In fact, as you saw with Blackbaud and other firms we discussed, it enables you to do an even better job of it.

Beyond the obvious financial benefits, having a purpose gives more meaning to your job, which, in turn, gives more meaning to your life. When you have a purpose that matters, you become more effective and productive on every level.

Selling with Noble Purpose makes you money. It also makes you happier.