Ifá Comes to Cuba

There was once a prince who had been exiled in disgrace from his father’s kingdom. Destitute and desperate, he went for Ifá divination to find a solution to his woes. Ifá told the young prince that he must offer sacrifice by going into the forest to burn his last remaining possessions, which were the very clothes off his back. Only through this final loss would he come to achieve the great destiny that awaited him.

Meanwhile, in a neighboring kingdom, the obá had died without children to carry on his reign. The obá’s babalawos consulted Ifá to seek a successor to the throne and were told they would find their new king naked in a forest next to a fire. With this, the babalawos quickly dispatched soldiers to the four directions in search of this man.

After wandering for days, plumes of smoke led the soldiers to the man they were seeking, where they found him just as Ifá had foretold. The soldiers clothed the young prince and brought him back to their kingdom to be crowned as the new obá.

Years later the banished prince returned home at the head of a huge army. His father went forward and knelt before the obá who then revealed himself to be his own exiled son. After a tearful reunion, the obá returned to his adopted home to reign in peace and prosperity for many years.1

“The patient man will be made King of the World.”

Adechina had little time to waste. Through Ifá divination, the young babalawo from the crumbling empire of Oyó had been warned about the slavers who were on their way to capture him and drag him away in chains to a life of slavery. Adechina pushed away thoughts of making a run for it as he prepared to feed his Ifá tools with the blood from the two dark hens in anticipation for the daunting task that lay before him. He was resigned to his fate, as Ifá had already warned him any attempt to escape would be futile. And his own oddun in Ifá, which had appeared on the day of his initiation, foretold that he was to lose everything in order to achieve his true destiny. Adechina knew what he needed to do and he was determined to do it, no matter the cost.

Adechina tore feathers from the back of the birds’ necks and let them fall onto Ifá as he chanted a traditional song we use in preparation for the sacrifice, “Yakiña, yakiña ikú Olorun, bara yakiña.” 2 He pulled on the skin on his throat in acknowledgment that one day his life would be taken just as surely as that of the little hen he was dispatching to the other world. “Ogún chorochoro (Ogún’s work is very difficult).” He then proceeded to pour the warm blood of the hens over his Ifá, adding palm oil and honey over his ekines to finish nourishing the material representation of the god of wisdom and knowledge he worshiped as a priest. “Epó malero, epó malero. Ayalá epó malero,” 3 he sang as he added the final ingredients to the mix.

Finally, with his Ifá now properly fed, he got down to the grueling task at hand. One by one he began to take the blood-covered oil palm nuts and proceeded to swallow them, the blood and palm oil now acting as a much-needed lubricant to help choke them down. In this way he would be taking his Ifá, hidden within his own body, to accompany him on the grim journey that awaited him. His plans were already set. Once on board the slave ship he would sooner or later pass the ekin nuts, whereupon he would set about painstakingly cleaning them and hiding them on his body. Through pain and prophecy and animal sacrifice, as well as determined self-sacrifice, Ifá made the arduous journey to Cuba smuggled within Adechina’s own body.

The Yorubaland of Adechina’s time was quite different than it is today in a number of important ways. In Adechina’s day there was no such thing as a Yoruba nation, but merely a group of people and nations in the Southwestern part of what is now Nigeria. Up until the mid-1800s there was not a Yoruba identity, only a large number of nations organized in the form of city/states that spoke various dialects of the same root language. They also claimed a shared origin in the spiritual capital of Ilé Ifé, whose progenitor, Oduduwa, had come to Ilé Ifé from somewhere in the East. Finally, they shared the belief in a large pantheon of gods and goddesses, called orichas, who rule over the forces of nature and various human endeavors. Instead of a Yoruba nation there was the Egbado, the Egba, the Ijebu, Ibadan, the Owo, the Ijesha, and Oyó, among others, who were in a constant state of flux with shifting alliances and antagonisms being the norm.

Christian missionaries first conceived the idea of a Yoruba identity in an effort to unite these disparate peoples, and the word Yoruba itself is a term borrowed from the Hausa peoples to the North, who used it to describe the people of Oyó. These same missionaries also created the first Yoruba dictionaries in their bid to mold the various city/states into a single, albeit Christian, Yoruba identity.4 In each area they would often worship different orichas, or the same oricha might even have a completely different name. Each oricha cult competed with all the others, and priests of different orichas never formally interacted with each other or participated in each other’s ceremonies. Each oricha sect also had their own religious center in the form of igbos (sacred groves) where major ceremonies and initiations were performed. These igbos carried the name of the oricha, so you would have an igbo Ochún, an igbo Yemayá, an igbo Obatalá, and so on. These igbos were extremely private, and only priests of the oricha were allowed to enter. Not even the priests of other orichas were permitted entrance. The only exceptions were the babalawos and the obá who were considered high priests to all the oricha groups.

The orichas who enjoyed a wide popularity had their religious centers, or capitals, as well. For example, the worship of Ochún, who in Africa is considered the oricha of the river bearing her name (in Cuba she is regarded as the owner of all fresh or sweet waters), was based in Oshogbo in what is now known as Ogun State, even though she was worshipped in igbos all over Yorubaland. And Changó, the Warrior oricha of fire, thunder, and dance hailed from the great empire of Oyó. Some orichas, like Oshossi, might be extremely popular in one area, but travel a hundred miles, and he might be completely unheard of.

The ceremonies and rituals for the worship of each of the orichas differed from one another, and the priesthoods of the various oricha groups didn’t intermingle often, nor would they share their secrets with one another. The worship of even the same oricha might differ from area to area, with rituals specific to each area being incorporated. New rituals and changes to current rituals sometimes arose, not out of whim or convenience, but most often to commemorate an important event where the oricha had intervened on behalf of the people of that particular city or out of great need. One became a worshipper of an oricha in one of three ways: through family lineage where one’s parents, grandparents, or other relatives were worshippers of that oricha, by becoming possessed by an oricha, or if directed to worship an oricha by Ifá.

Ifá divination, which speaks for all the orichas as well as Olodumare, was by far the most important and most trusted oracle in Yorubaland. Followers of the different orichas, including their priests, would regularly consult with babalawos on every major aspect of life. Infants were regularly brought to an Ifá priest a few days after birth to learn the innermost nature of the child and which oricha the child should grow up to worship. While the oricha cults employed their own form of divination called merindilogún using sixteen cowrie shells specially consecrated for this purpose, it was mainly used on ritual occasions to learn the will of the particular oricha being consulted. Although the sixteen cowrie shell divination system was derived from Ifá, it was far simpler, having only sixteen odduns of which only twelve could be read, with clients being sent to a babalawo if one of the other four odduns appeared.5

In fact, Ifá was the one thread that held these separate cults together as a systematic whole. Only within the body of knowledge called Ifá did the various orichas and their worship exist together in one place or achieve a cohesive whole. Histories, prayers, orikis (prayers in the form of praise chants), and rituals for the various orichas were all recorded in the massive compendium of oral tradition that was Ifá. This would later prove crucial when the Yorubas were forced to re-create these practices as slaves in the harsh, alien world called Cuba.

An old Chinese curse, “May you live in interesting times,” is supposed to be one of the worst curses that can be inflicted on a person, and most eras that are interesting to historians are indeed horrific to those who are unfortunate enough to live in them. The 1820s Yorubaland that Adechina was living in was one of the most interesting times in the entire history of Yoruba culture. The great Oyó Empire was actively involved in the European slave trade and tearing itself apart from the inside, with the royal family engaging in intrigues that would make Machiavelli or the Roman Caesars blush, having gone through five Alafins (Emperors) in less than twenty years. Many of the nations who had lived peacefully under Oyó rule for so many years were now in open revolt. When not warring amongst themselves and the kingdom of Dahomey, they were making regular incursions into Oyó territory in search of slaves and conquest. From the north the Muslim Fulani were attacking, and the dark hand of European colonialism was reaching toward Oyó, grasping at the neck of Yoruba culture. Ambition and greed became so overwhelming in the Oyó Empire that the Alafin Awole, who had come into power by murdering his own father, went so far as to violate the sacred oath made by every Alafin never to attack their spiritual homeland of Ifé, by sending his top general Afonje to lay siege to the market town of Apomu in 1795. This led to a mutiny led by Afonje himself.

This order pushed the popular and powerful Afonje over the threshold, and the general and his army mutinied against the Alafin. Soon after, the Alafin Awole was sentenced to death by suicide by the babalawos of the Royal Council, known as the Oyó Mesi, for his crimes after consulting with Ifá. An unrepentant Alafin Awole cursed his own people by shooting arrows into the four directions and damning his own rebellious subjects to be carried off as slaves to the four directions, just as the arrows that he had dispatched. In short, the Yoruba world was collapsing.

The number of Yoruba slaves brought to the New World primarily came in two waves. The first took place around the 1770s, and the second and greater of the two occurred in the 1820s, which is almost certainly when Adechina was brought to Cuba. The first wave, which coincided with the opening of the slave port in Lagos, had Yorubas comprising fifty-eight percent of the slaves being brought over. The collapsing Oyo Empire was largely responsible for the second wave where Yorubas made up eighty-one percent of the slaves being sent to Havana.

Although the Spanish signed a treaty with the British to end the slave trade in 1817, illegal slave ships regularly evaded British and Spanish blockades to deliver slaves to Cuba. Though officially illegal, the slave trade to Cuba was burgeoning, and between 1826 and 1850 more than 65,000 Yoruba slaves were brought to Cuba, and it wasn’t until 1867 that the last slave ship landed in Cuba.

As we saw, when the slavers came to drag Adechina off to a life of slavery, he swallowed his Ifá implements, concealing them inside his own body. Who were the slavers who captured Adechina? Were they invaders from Dahomey or another Yoruba kingdom, or was the raid perpetrated from Oyó itself? If so, was this act produced from the Alafin’s unbridled greed or was it caused by yet another palace intrigue in revenge for some slight, real or imagined? Sadly, we may never know.

We don’t know the exact year Adechina arrived in Cuba, as the slave ship that carried him was illegal and undocumented, but it was most likely in the late 1820s. We do know that upon his arrival in Cuba he was given the name Remigio Herrera, his surname being taken from Miguel Antonio Herrera, who owned the massive Samson y Unión plantation. We also know that with his exceptional intelligence Adechina was eventually able to win the favor of his masters and insinuate himself into their good graces. This was rewarded by him being allowed enough freedom to serve as a courier, running errands between his owners’ plantation near Matanzas and the capital of La Habana. It was on one of his trips that he stumbled upon another enslaved babalawo, Adé Bí, who had arrived some time after Adechina.

Adé Bí, whose own oddun was Ojuani Boka, had also gained favor with his masters, but in his case, it was directly through his abilities as an Ifá diviner. He had gained the trust of his own masters through the use of an ecuele he had constructed out of dried orange peels and a string taken from a majagua bush, which he used to advise his masters on their various business negotiations. Because of the accuracy of his predictions, Adé Bí gained the full trust of his masters and was permitted to come and go almost at the will. Eventually, he was given his freedom because of his help in predicting the outcome of a particularly large deal for his owners through Ifá divination.

During their conversation, Adechina informed Adé Bí that he had managed to smuggle his Ifá into Cuba and that it needed to be ritually washed and fed. Due to the esteem that Adé Bí’s owners held him in, it was not difficult for the babalawo to procure the basement of a bodega in which to do the cleaning and feeding. Two days later, Adechina divined with the newly washed and fed ekin nuts as is traditionally done, and the oddun that came up was his own sign, Obara Meyi.6 Probably sometime in the late 1820s, other Lucumí slaves recognizing Adechina’s stature as an Ifá priest got together and bought his freedom. Soon afterward he founded a cabildo (religious council) in the Simpson district of Matanzas, where he worked as a babalawo and began his meteoric rise among the Lucumí religious community in Cuba.

The babalawos’ training had imparted in them an encyclopedic knowledge of the various orichas, their rites, prayers, and the relationships between them. This became the crucial link necessary in recreating the complex religious world among the Lucumí slaves whose cultural and spiritual identity had been shattered by the institutionalized terrorism of slavery. Central to achieving these ends was the institution known as the cabildo de nación (ethnic councils).

The Spanish encouraged them to form these cabildos and saw them as a means of control and to prevent the possibility of slave uprisings. For the Lucumís the cabildos became central to the survival and re-creation of their culture and religion on the island. They served as mutual aid organizations, amassing funds to buy their brethren out of slavery and to aid the sick, the infirm, the elderly, and those in need. Just as they had done in Africa and in many indigenous cultures throughout the world, the babalawos and the santeros did much of their rituals and work on behalf of the community in which they served. This is underscored on the Ifá side by the vow to serve humanity made by every babalawo during their initiation. For example, leading up to the New Year, the babalawos gather to perform a number of ceremonies and feed the different positions of the world for the Opening of the Year ceremony. This is done to ensure the well-being of the community and the whole world.

We conduct special rituals for Orun, the sea, the river, the sun, the moon, the stars, the wind, the hills, the rainbow, the dawn, the cemetery, waterspouts, certain sacred trees, and so on, and they are all fed in the process. These huge ebbós are called Olubo Borotiri Baba Ebbó, or Father of All Sacrifices, as they are for the entire world. This all culminates in the babalawos performing deep divination to find out the Ifá oddun that rules the year, which is now published by many of the world’s newspapers. After weeks of ceremonies, a tambor begins for the orichas, and everyone is welcome to this party. The cabildos became a little piece of Africa with the focus always on the well-being of the community and the world. These cabildos exerted a tremendous amount of influence on how the religion is practiced, even to this day. Nearly all of the Lucumí cabildos were founded and run by a commanding combination of babalawos and powerful santeras who conducted the vast majority of ceremonies up until the 1930s, many of whom were also married to babalawos. Later, as the age of the cabildos faded to a close great babalawos such as Tata Gaitán, who would later become installed as the obá over the religion, operated their own homes under the same principle of aid to the community that had guided the great cabildos.

The reconstruction of oricha worship in Cuba entailed great changes from the independent, competitive oricha cults of Africa. In Africa most priests did not receive orichas to take to their homes upon their initiation. Instead the orichas remained at the main igbo center of their particular oricha. This form is now all but non-existent in Cuba. Those who did directly receive orichas received only their oricha and Elegguá, a practice called cabeza y pie (head and foot) in Cuba. This head and foot initiation eventually gave way to the kariocha (initiation ceremony), introduced by the powerful Havana santera Efunché, where Eleggua (Elegba), Obatalá, Ochún, Yemayá, and Changó were received along with the initiate’s Olorí (tutelary oricha).7 In Cuba’s new compressed initiation process, the initiations to the various orichas, which were often very different from one another in Nigeria, were now all performed using the initiation to Changó as a model with minor variations to accommodate the various orichas. The babalawos participated heavily in these ceremonies, at times being charged with performing everything from the pre-initiation consultation and Ebbó de Entrada (Entering Sacrifice) to cleanse the initiate-to-be before entering the initiation room, to shaving the neophyte’s head, blessing the plants used in the ceremony, and performing the animal sacrifice.8 The very name of the room where oricha initiations are held, igbodún, is a testament to the enormous influence of these babalawos. Igbodún is what they called the Ifá grove in Africa.

Of course, with great change comes great struggles between different factions, and babalawos played their part in those as well. Miguel Ramos’s fascinating paper La Division de la Habana, depicts in great detail one such epic war between the great priestess Ma Monserrate (Obatero) who battled for supremacy against the combined forces of two other exceptionally powerful priestesses, Latuán and Efunché. When Ma Monserrate lost the war, it was Adechina who accompanied her to Matanzas and installed her at the helm of the cabildo he had founded soon after gaining his freedom. He topped it off by commissioning a set of batá drums from the babalawo and co-founder of the drumming tradition Atanda, playing them in a tambor to commemorate her inauguration as the new head of the cabildo.

The babalawos were instrumental in reviving the sacred music of Africa as well. The batá drumming tradition was created in Cuba when the babalawo Atanda partnered with another drummer, Aña Bí, to consecrate the first batá drums in Cuba, and teach others in the religion the complex rhythms needed to praise and bring down the orichas to possess their initiates. In Matanzas the oral tradition insists the drumming tradition there was transmitted by none other than Adechina himself.

Of course, Ifá itself had to be reconstructed on the island, but here the babalawos had an almost insurmountable hurdle to overcome. The babalawos now realized they had an immense problem on their hands. If they didn’t initiate new babalawos, the secrets of Ifá in Cuba would go to the grave with them. The physical secrets of Odun (commonly referred to as Olófin), a manifestation of the Supreme Being and the highest power in Ifá are, like the orichas, received physically by the initiate and are absolutely necessary for the initiation, but they didn’t exist in Cuba. Therefore, it was impossible to initiate a new babalawo without her being present in the igbodún (igbo Odun or Odun’s grove), the initiation room named after her. Not only would any attempt to initiate a new babalawo without her presence be a grave disrespect and sacrilege to her, the ceremony would not be recognized by Ifá and would therefore be worthless. So the only way new babalawos could be initiated in Cuba was for a babalawo to risk everything to return to Africa to receive Odun, and then attempt to sneak back into Cuba with her. Even the best possible scenario would involve months of enduring the difficulties of sea in each direction. And there was the very real possibility of jail or death if anything went wrong. Although the attempt to return to Africa and smuggle Odun back into Cuba was incredibly dangerous, plans began to be hatched and refined in secret. Most babalawos agree it was Adechina himself who made the attempt using the code name Odun, and in fact received Odun/Olófin twice while he was in Africa.

The first babalawos to come to Cuba knew Odun was absolutely essential to the initiation of new Ifá priests. If you add to this the extreme hardships these babalawos were willing to endure in order to bring Odun to Cuba, it becomes much easier to understand why Cuban babalawos are adamant in refusing to recognize any Ifá Priest initiated without her being in the room. That point is simply non-negotiable for us, and it is difficult for us to view it as anything but an outrageous insult, not only to our traditions, but also to the early babalawos such as Adechina who went to such lengths to preserve them. To us, the lives of the slaves who acted with such courage and brilliance have worth, and we are offended by those who imply that they don’t.

Once Odun was smuggled into Cuba it was possible for new babalawos to be initiated, and Adechina initiated several Africans such as Ño Akonkón Oluguery (Oyekun Meyi) and Ño Blas Cárdenas (also Oyekun Meyi), as well as one or two Cuban-born Creoles.9 In turn, Oluguery initiated the famous Eulogio Rodriguez “Tata” Gaitán, who is considered the head of the particular rama (Ifá line or branch) I belong to, with Adechina acting as the oyugbona, or second padrino. Unfortunately, Oluguery was not able to fully train Tata Gaitán as he left Cuba to return to Africa, dying in Mexico during the attempt, which left Tata Gaitán to get much of his training from Oluguery’s brother in Ifá, Ño Blas Cárdenas.

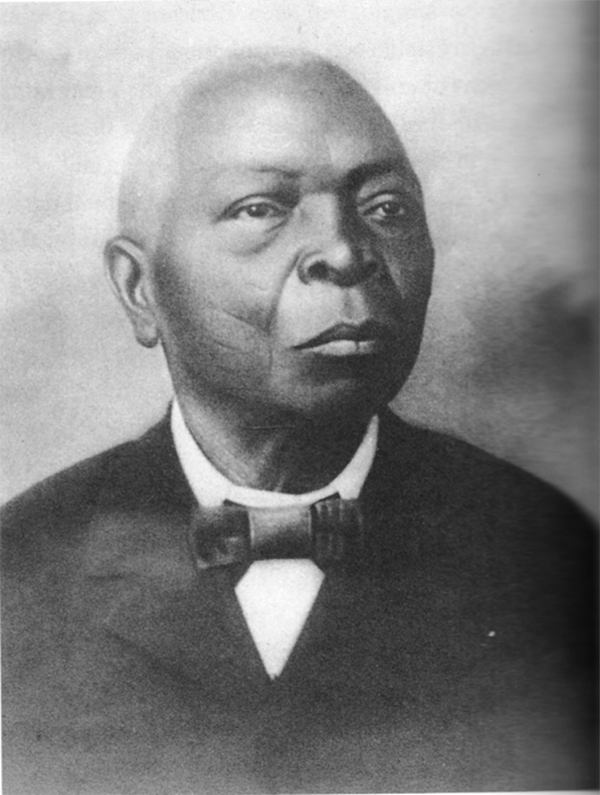

During this same period in the 1860s, Adechina moved to Regla, which is across the bay from Havana. There he founded the famous cabildo de la Virgen de Regla, the saint associated with the oricha of the sea Yemayá, thus helping to give root to Ifá in the Havana area with it eventually becoming the stronghold of Ifá in Cuba. Over the years, Adechina became such a revered and powerful babalawo that people from all walks of life were known to spontaneously kneel and kiss his hand when they would encounter him on the street. Up until his death on January 27, 1905, Adechina selflessly taught his godchildren and their godchildren. After his death, Adechina’s cabildo was led by his daughter Josefina, affectionately known as Pepa, and became famous for the massive processions they would hold for Yemayá every September 7 (the feast day for the Virgin de Regla) with batá drums layered with the songs sung in her honor.

I chose to put the patakí taken from Adechina’s oddun at the beginning of this chapter to illustrate how closely Adechina’s life followed his oddun in Ifá, Obara Meyi. Every babalawo is born as a child or personification of one of the Ifá odduns. As expected, the child of Obara Meyi is almost certainly predestined to lose everything up to, and even including, their very clothes, only to rise again over time like a phoenix from its ashes to become even greater than before. Adechina lost everything when he became enslaved and drug off to Cuba, but over time he was able to achieve a greatness and success in Cuba that he may not have achieved if he had remained in Africa. Obara Meyi is also an oddun of wisdom where the chain of learning from teacher to pupil was born just as most of Cuban Ifá comes from Adechina’s teachings. This oddun is also one of the principle signs of commerce and financial success that certainly came to the ex-slave Adechina, giving us an outstanding example of how the events and traits in a person’s life will reflect the oddun they embody.

Adechina was truly a great babalawo not merely due to his seemingly inexhaustible wealth of knowledge, wisdom and compassion, but because Ifá and babalawos would not even exist in Cuba if it weren’t for his selfless actions. His willingness to risk life and limb—not once but twice—to give birth to Ifá in Cuba and nurture it to fruition is just now bearing fruit. Thanks to him, Santería is now a world religion and a treasured part of Cuban heritage and culture.

In an ironic twist, Santería has now come to the aid of the religion in Africa itself, as the explosion of interest in Santería has led more and more people to explore the religion’s roots. In turn, the sudden leap in interest from outsiders has caused many Yorubas, taught to look upon their own religious roots as backwards and primitive, to look at their heritage with new eyes and with a renewed sense of pride. Oricha worship in Yorubaland, which was in serious decline due to the effects of colonialism and the attitudes that came with it, is now growing by leaps and bounds.

Adechina (Obara Meyi)