While I was specifically not rocking the casbah in Morocco, Matt was finishing the label for Origin, hand-drawing the art and emailing me drafts to review over mint tea and tagines. We planned to launch early that summer. We were evolving the idea of Genesis 10:10, our limited-edition anniversary beer, dropping the alcohol content to eight percent, having decided to produce a more “sessionable” imperial pomegranate amber ale. It would be the first new permanent addition to the lineup since Messiah Bold.

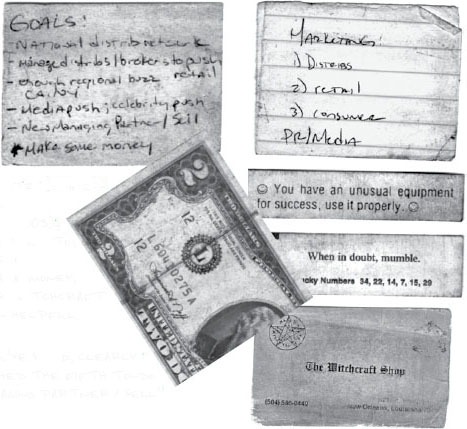

We had already started work on a new beer that I coined Rejewvenator. The entire idea hadn’t yet crystallized in my head, but I knew Rejewvenator would tie directly into the sacred species listed in Deuteronomy, by incorporating a different sacred fruit into the brewing each year. As I walked though foothills and valleys, towns and villages throughout Morocco, these same sacred fruits grew in abundance everywhere I went. Hiking through outposts of forgotten sand and stone fortresses, or on treks through the lush oases beyond the gorges and into mountain valleys high above the desert, every day revealed stunning vistas and even more beautiful groves, overflowing with all the sacred species — pomegranates, figs, dates, olives, grapes — everywhere I turned. Tiny tributaries pulled off the river coming out of the mountains, feeding small farmers’ plots and sustaining the strings of tiny villages that stretched far into the landscape. I assumed this was what Eden must have looked like.

For Shmaltz Brewing, Origin thematically represented a new beginning. Genesis was our flagship, our first creation. Genesis, Chapter 10, charts the descendants of Noah’s sons. We tend to think of ourselves as descendants of Adam and Eve, but in reality — or the reality of mythology — all people are more directly descended from Noah and the presumably hearty (and biblically unnamed) Mrs. Noah. When the dove brings the olive branch, revealing the dry ground after the receding of the flood waters, Noah first offers up a little charbroiled sacrifice, but then, immediately after receiving a renewed covenant from the divine, he plants a vine, the first act marking the renewal of life19.

After ten years of He’brew, we were moving into a new phase for the business, hopefully from a more established and experienced place. Origin would be our first permanent new product. (At the time, we didn’t realize that Bittersweet Lenny’s would become a year-round offering. But you just kept ordering it, so we just kept brewing it.) Today, with its balance of a big, rich malt profile, plenty of hop presence, and just a hint of unique tart and sweet from the pomegranates, Origin continues to be a real favorite of people at beer festivals and trade shows. The beer recently won People’s Choice Award at the wildly attended Atlantic City Beer Festival.

With Coney Island Lager coming for summer, we were preparing to go into the draft business in a much bigger way for the first time in the company’s history. At exactly that moment, we ran into a major crisis.

I’d had been working with Microstar, the only keg-leasing company in the business, for nearly a decade. I got an email from the C.E.O. saying they were canceling my contract.

I’d started taking a few kegs a month when I was with Anderson Valley, and I probably averaged ten or fifteen kegs a month over the seven years I’d been under contract, with an occasional bump from a round of seasonals. When they threatened to cancel, I had nothing but excuses: I was so bad at bookkeeping — living on the road, having mail forwarded, and writing checks from diner counters and friends’ coffee tables — that I was constantly behind on my payments.

Ken at Anderson Valley often thundered about the keg problem. I can hear every brewer thinking about how to track rogue kegs, how to pull empties out of basements or backyards, to load onto trucks to bring back to the brewery. Especially for a small producer with wide distribution, Microstar is simply the only option. If they don’t lease kegs, breweries have to buy their own. When they ship them around the country, they inevitably start losing them fairly quickly. They’re an asset that starts hemorrhaging.

New kegs cost about seventy or eighty dollars until 2003 or so, when the prices started going up. Even used kegs jumped from forty to fifty, mirroring the increase for new ones. In perfect shit-storm fashion, the minute Microstar started rumbling about my contract, the price of new kegs began to skyrocket. Part of the problem was that the scrap-metal value of a keg had gone up to thirty dollars, and bars and retail customers still only paid the ten-dollar deposit that was industry standard across the country. People were simply taking them to scrap yards to cash in. As a result, kegs were disappearing all over the country, every month.

At the same time, one of the major keg-manufacturing facilities closed down completely. Suddenly, buying a new keg rose from eighty dollars to a hundred twenty to one-eighty in a flash. Used keg prices followed suit. That meant if you were even selling a couple hundred kegs a month, you might need well over a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of kegs to maintain that float, many of which were likely going to be lost, stolen, or scrapped.

I, of course, freaked out. Then I got on the phone, and I managed to beg and plead and scrape together just enough kegs to prepare for Greenpoint’s first run. I bought old kegs in any condition from defunct breweries that were still sitting at some of my wholesalers around the country, and I paid the cost of shipping them to Brooklyn. (Any remaining inventory would all be gone shortly, when all the small brewers hit the same hysterical call buttons.)

At the height of the mayhem, in a dumb-luck moment of timing, Kelly and I happened to be online the same day, and we found out that a couple of German breweries had consolidated and were selling off old kegs. Rick at Schaefer, another in a long line of superheroes to save my butt at exactly the right moment, said, “We’ll sell you as many as you want, for X dollars a keg.” (Not that it was some profound trade secret, but I promised I wouldn’t mention it. Suffice to say it was way below new keg pricing, and significantly below any load of used kegs we could find.) We bought two container loads from them, which meant, for my portion, I had to come up with about a hundred grand — in thirty days.

Without owning a brewery, I certainly didn’t want to own my own kegs. We agreed that Kelly would start buying them back from me as we needed them for contract brewing, hopefully putting several hundred into rotation right away and growing from there.

At that point, Matt stepped up in a huge way and saved me. Several months before, after a beer fest and a few late-night samplers, I’d called him and blurted something I’d been thinking for some time: I think you should quit your job (of ten years, full benefits) and work with me full-time (way more than full-time, and no benefits). I’m not sure what the hell might happen, or when we’ll get health insurance (October, 2010), but come on, man! Let’s blow this thing up! Let’s make history!

Though Matt had been my creative partner for some time, crafting much of the visual character of the brands, he now threw himself all-in, becoming the other Shmaltz guy and my New York and east coast general. He also took out fifty thousand dollars from his and his incredibly indulgent wife’s home equity line, and he handed me a check for half the keg cost. I called every credit card balance-transfer option sitting in my P.O. box, fudged some income numbers to bump up my credit lines, and got the rest from zero percent offers that would last a year or so.

Without a brewery, or even an office, or a landline, Shmaltz Brewing owned fourteen hundred kegs, with nowhere to put them. So we stacked them to the rafters at the brewery at Greenpoint, and Ralph agreed to store them in a giant locked yard at S.K.I. We even stacked them in a parked big rig in Saratoga. At eight kegs to a four-foot-square pallet, fourteen hundred kegs made… a lot of stacks.

The keg issue was a big deal, even beyond my little universe. It was reported in the major media across the country. To its credit, the beer industry, led by the big beer companies and the big beer wholesalers, recognized the problem and moved on it quickly. Deposits were tripled, to thirty dollars per keg. Laws were passed making it illegal to sell kegs to scrap yards. Impressively, everyone pulled together, and the problem was soon overcome. Three years later I still own over a thousand kegs, though I will be selling them all shortly. Any takers?

Until that point, we were moving five or so kegs a month in New York City, and about twenty around the country. I knew draft was about to pick up for us, so I begged, pleaded and, most importantly, agreed to pay Microstar C.O.D. To their credit, and through the steady helmswomanship of Lauri, the C.E.O., they gave me another shot. We’ve grown our draft business substantially since, year after year, up from those twenty a month to well over four hundred per month with Microstar and another four hundred or so per month of my own kegs in New York.

Back in San Francisco at the end of that winter, the I.R.S. came knocking with my first official tax audit. For our first meeting, I was once again crashing at my mom’s for a few weeks. By our second, I’d found a sublet back in San Francisco, on the corner of 17th and Mission, just down from the rent-by-the-hour flophouses and two hundred feet from the donut shop that doubled as the local crack-addict and heroin-junkie encampment. Thanks to two musicians touring Europe and the magic of Craigslist, I actually had a great little apartment, just a few blocks from some of my favorite bars and restaurants in the city. But the auditor was, understandably, more than a little skeeved by the neighborhood. I told him not to leave anything in view inside his car, and to bring a lot of quarters for parking meters if he planned to stay awhile.

For 2005, I’d gotten my sales up to about $350,000, up from maybe a hundred and thirty grand at the height of my 22 ounce business days. All I had to show at year’s end, however, was $12,000 left over as profit — my “salary.” Michel, the I.R.S. investigator, who reminded me a little of Inspector Clouseau, came to my mother’s house for our initial meeting. He explained that I had a small business that was growing a lot, and there were certain things that set off investigations — the dreaded “red flags.” “You’ve gotten big enough for us to be curious,” he said. True, the business had grown, but I was still spending any gross profits, traveling constantly, and just scraping by.

Michel said, “Please let me take a look at the receipts, so I can start building a file.” I said, Here’s my tax return. Well, did I have my backup paperwork? No sir, that’s it. No bank statements, no credit card receipts. No invoices, no purchase orders, no proofs of payment. For the last couple of years I’d joked with Matt every time a receipt made an appearance. What’s the point? I figured, It’s just more stuff to shlep around. And break even is break even. I told the auditor, Seriously, I don’t have a single receipt. He was astounded.

“Er, this is somewhat of a unique situation for me,” he said. Most of the time, he joked, people were so angry with the auditors, they open the door to a dank basement stuffed with boxes containing years of receipts, none of them marked, and say, “Go ahead.”

Over the course of several meetings, we slogged through. I had the brewery run a report for the invoices I paid. I asked my vendors to send statements for the year, and I got my bank statements from Wells Fargo. I said, You can see how much went in and out of my business bank account. My personal bank account was equally unimpressive — a few grand here and there, matching up with the business profits.

It went back and forth like that for several months, a bit of a war of attrition, for some time before Michel and I finally came to a settlement. In the end it came down to about eight thousand dollars I couldn’t “prove” I’d spent. Michel got promoted and, having reported back about my mother’s guest room, the crack-corner sublet, and a reasonable effort to reconstruct an entire year of my life, they closed the file and moved on. The end result: $1252 in income tax for the I.R.S. locked and loaded, for weeks, if not months, of this guy’s attention.

QUITE A RUN FROM ‘97 - ‘05. NOT TO MENTION THE REST.

Happily, I survived my first audit with my sense of humor intact. And the episode did inspire me to start thinking about changing my bookkeeping practices.

I’ve begrudgingly learned to take better care of my paperwork. I tell all my vendors that I run a “paperless” company. Most are happy to use email, though somehow I still manage to get piles of unnecessary envelopes forwarded to me whenever I’m on the road for work.

Similarly, for ten years I received my depletion reports — wholesalers’ statements of the amount of our product they’re selling — and promptly threw them away. Again, neither trained nor predisposed as a sales manager, I figured I’m on the phone with these guys or selling beer in their cars with them fairly regularly, and I know if there’s a problem. Let’s just go sell as much as we can, and we’ll worry about the numbers one day, when I’m not just scrambling for survival.

After a basic template that Angela and I created to start tracking this “stuff,” and after probably two hundred phone calls just to get all the depletions sent monthly (you know who you are, you naughty non-reporting distributors), we evolved to the next step with the help of intern-turned-post-biz-school whiz Kevin Friedman. My old “vice president” helped his cousin Leah and me create a monster Excel file to track our wholesalers’ monthly, quarterly, and annual sales.

That spring, on Mother’s Day, I had a business meeting with a potential employee at a well-worn, well-loved, bike-messenger, dope-smoking, Mission beer garden called Zeitgeist (their motto: “Warm Beer, Cold Women”). Zak would end up becoming my west coast regional sales manager. The year before, he’d hired me for an event at U.C. Davis through Hillel, the on-campus Jewish student organization. After ordering pints of Racer 5, we had a great discussion about Jewish entrepreneurship. Later, we ran into each other at a beer festival in San Francisco, and Zak was putting out the feelers with tech companies. Within a few months I had hired him to work for me part-time, which quickly became full-time.

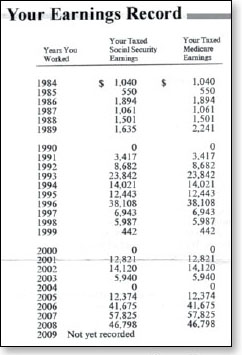

It was wonderful to have somebody so young, enthusiastic, and capable, someone who was also interviewing at Google and Yahoo, who somewhat astonishingly considering Shmaltz Brewing as a “legitimate” career direction. Compared to the days when Rob had the same thoughts, slowly but surely, Shmaltz was crawling toward becoming an actual company. We were starting to have enough products, revenue, and mojo in place. I still, however, had my entire marketing plan on a Post-it note in my wallet, where it had already been squirreled away for years.20

SHMALTZ BUSINESS PLAN #2 (CIRCA 2003):

1. MARKET TO PEOPLE,

2. MAKE MONEY,

3. USE WITCHCRAFT WHEN HELPFUL.

AS YOU’VE READ, CLEARLY I DITCHED THE FIFTH TO-DO “MANAGING PARTNER / SELL”

With fifty thousand dollars of his home equity at risk, Matt officially came on full-time as my art guru and east coast sales manager, better known as “the other Shmaltz guy.” He’d been working at a small Midtown design firm churning out trade show booths, UPC code changes on packaging for sample boxes, and anything that needed to be communicated by various members of extremely-corporate America. I said, It sounds like you could use a bit of creative inspiration — every day.

Typical of Shmaltz: The things that have been most successful for me have started casually and personally. Very rarely is there a well-thought-out, pre-planned business decision. I don’t necessarily advise this for everyone, but it’s worked for me.

Matt and I had been introduced by our mutual friend, Peter. They grew up together in Milwaukee and continued to watch every Packers game together at the Kettle of Fish in the West Village. One spring break, visiting Peter at college, Matt received a rush offer at a frat house at Stanford — though he was still a senior in high school. He was just visiting the campus, had not even applied to Stanford, and had no intention of going to school there. Repeated beer bongs filled with goldfish floaters and slash marks on faux-samurai headbands marked his “progress.” Making friends and drinking beer — early talents.

After redoing my website, Matt designed the first Jewbelation label for my eighth anniversary in 2004. By 2007, he had created more beer labels, business cards, sell sheets, posters, and postcards for the company than any other designer, and it continues to this day — twenty-three beer labels and counting. He has created the entire visual landscape of Shmaltz Brewing, and made it spectacular.

Matt had a friend in New York he’d grown up with who was an investment banker. We met this friend at the Kettle of Fish so I could ask him one question: How do I finance this business?

Sales were growing, and I simply needed more money to cover it all. I’d passed the “cusp” of breaking even every year for the past couple, and every month the bills for the contract-brewed cases increased as our sales continued to increase. Good problems to have, for sure, and certainly better than the alternative scenarios of my first seven years in business. However, with the keg purchase tying up so much of my working cash, I needed to find a solution to buy more beer — more inventory — so I could keep it rolling to my wholesalers and the market.

As I’d explored previously but couldn’t quite clarify in my head until those few pints with Matt’s buddy, my options were few. 1) I could gather my life savings — of which there were none; 2) I could raise equity by trying to sell a portion of the company, once again asking friends and family, or look for angel investors like I’d done in 1999 (though the memories of that first round were still painful, and I was far from clearing those assumed obligations); or 3), I could take on more debt.

In order to get a bank loan, a small business owner needs to personally guarantee that the lender can liquidate your life and all your assets, if necessary, to cover the nut. I had nothing to offer a bank other than a couple years of slightly profitable and aggressive growth. No house or brewing equipment, or anything else more tangible than my best intentions. So the only solution I could see was to crank up my credit cards once again.

There’s no question that if our country hadn’t been so ridiculously overzealous about feeding the economic bubble before the current recession, I never would have made this whole enterprise work. It’s the only way I survived. When I’d call about another credit card offer that came in the mail, they’d say, “Mr. Cowan, could you please tell me your annual income?”

And I’d say, Oh, sure. $286,000. “OK, great. Here’s a $37,000 credit limit.” Then I’d turn around and spend it all — on beer.

My old investor Russ - the same Russ whom I bailed on for breakfast in the year of the bender — once said something that sticks with me to this day: “To make any business work, you need to be prepared to do the everyday work, every day. So much of this kind of stuff is just doing the blocking and tackling.”

Blocking and tackling — that sounded to me like the worst possible part of the job. Reminds me of my head in the scrum in college, with a broken pinkie and a bloody schnozz.

By this time, I was routinely fighting the fact that the job demanded so much blocking and tackling. My friend Jon, who owns a wine company, has become a wonderful advisor over the years, and he’s heard me complain about it. To this day, he’ll call and ask for the “Blocking and Tackling Department” of Shmaltz Brewing, just to piss me off.

It’s simple stuff: checking in with customers, and reminding the market over and over about yourself and your products. Checking the costs of your ingredients, and packaging and negotiating better deals. Watching trucking costs. Keeping your receipts. Being consistent in your plans and demands from wholesalers and reps. Paying bills and, most importantly, getting paid on time — and then turning around to buy more beer and more packaging. And keeping a steady pace, without letting too much fall through the cracks.

In short, for a restless entrepreneur, brutal. But so important. Consistency and reliability — they’re no secret to so many success stories. I suppose the words are on those glossy corporate posters at Office Max for a reason.

Blocking and tackling doesn’t mean, however, that you’ve got to stand still. After many years of having one and then just two beers, that’s what made the more recent growth of the company so exciting. Yes, things were stressful, and we were constantly behind. Yes, the new products were likely creating distractions and spreading everyone way too thin. But the industry loves what’s new, and we loved whipping out what we considered fresh art projects in the form of beer.

Right from the beginning, we had a great response from the community for Coney Island. I had been selling maybe five or ten kegs of He’brew a month in New York City. In the first month with Coney Island, S.K.I. sold probably eighty kegs. The next month it was a hundred and ten, and the next one-twenty-five. Same distribution, same quality of product, just a different name and different shtick.

It did change our ability to reach a lot more people. The reputation and experience of He’brew made people respect and appreciate, and become aware of, Coney Island rather quickly. Conversely, the familiarity of the Coney Island name got us into a ton of bars, and we were able to bring He’brew into many of them. It was a good symbiotic relationship.

That summer, despite the unearned largesse, my buddy Craig’s close friend Cathleen rented me her Brooklyn apartment way below fair market cost. Her generosity landed me my best sublet ever: air conditioning, multiple bedrooms, elliptical machine — a huge advance in Shmaltz sublet history.

In this spirit of expansion, and with a guest bedroom to offer, I asked my friend Eva, who happened to be coming from Minneapolis to visit family in New York, to help me plan the entire future of Shmaltz Brewing… for free. A good friend from our New Orleans post-collegiate youth, Eva had worked for several consulting firms, and by this time she was running her own one-woman show, charging large sums of well-earned dollars. Again, angels share much more than I can repay.

She created a master spreadsheet for the company that connected the costs of all the products to sales dollars from each brand, and then she outlined the potential expenses necessary to achieve three scenarios. We plotted conservative to moderate to aggressive sales increases to get a sense of the money landscape that could roll out before Shmaltz Brewing. With many of the products in place or in the final planning stages, and with enough sales history to loosely ballpark what might happen if things went poorly, well, or gloriously, I saw a reasonably understandable bottom line emerge for the first time in over a decade. That blessed spreadsheet quickly became my Shmaltz Torah.

Armed with a little bit of knowledge, a lot more credit card debt, and very large sales growth, in the fall of 2007 I hired one more salesperson to cover the south and, I hoped, an even wider territory. Just when I was realizing the new hire wasn’t working out, one of the brewers from Olde Saratoga called me and told me he was moving to Atlanta. So Darren just kind of happened. Sometimes things work out perfectly — you get the feeling the universe is smiling down on you.

While brewing at Olde Saratoga, Darren had run the production for our first-ever barrel aging of Bittersweet Lenny’s. He’d grown up in Florida before landing in Atlanta, where he worked for a financial company. He was a homebrewer who wanted to go into the beer business, so he gave up his career-path job in the financial world to wash kegs at Sweetwater Brewing in Atlanta, where he started apprenticing. At Saratoga, he became a production brewer, and in addition to all his other full time responsibilities there, he single-handedly managed this great little barrel-aging project for me, pulling R.I.P.A. into Rittenhouse 100 rye whiskey barrels and babying that beer through to its glorious conclusion. That successful experiment grew into our current barrel-aging program kicking out R.I.P.A. on RYE, Vertical Jewbelation, Barrel Aged Blockhead, and 2011’s Genesis 15:15. Darren continues to be our special brewing project coordinator, and a key source of production knowledge to the company and to me personally.

While, on the one hand, the heavens seemed to be opening up for me on so many fronts, the other hand was preparing to spank my ass with a lot less love. In October I went to the brewery and had a meeting with Bob, the G.M., and Paul, the head brewer. That was the first time anyone mentioned the words “hop problem” to me.

As a contract brewer, I’d never taken the time to learn how hops were bought and sold. I knew that the intricate buds grew on vines, and I knew we used a huge array of them in our beers. I’d touched and smelled them whenever I was bouncing around the brewery “helping” brew up a batch of beer (read: staying out of the way). In the whole time I’d been in business, I’d never been involved in a single hop purchase, and I had no idea who the companies involved were. I had certainly never heard the two words that would haunt, in horrific fashion, myself and so many other small brewers: Hop Contract. Horrific, because we didn’t have one.

By November, people in the business were calling it a “hop crisis.”

Evidently, the year’s hop harvests in the U.S. and around the world had been exceptionally poor. To make matters worse, there had been a huge fire at a key hop supplier’s warehouse. On top of that, the craft industry had created a marked increase in demand for hops. Just about every small-to-regional-size microbrewery was making stronger single and double IPAs — Stone, Dogfish Head and so many others, creating the innovative products that new craft followers craved. Sierra Nevada, Sam Adams, even Red Hook and Goose Island had cranked up their hoppier offerings, slurping up pounds at a scale much beyond our modest annual needs. Suddenly, we had a big problem on our hands. And there was panic.

Conspiracy theories were rampant. For years, hops had been priced between two and four dollars a pound. Almost overnight they went up to ten, then sixteen, then twenty-three dollars. At the height of the situation, the only way I could get any Cascade hops (used in nearly all our recipes) was to touch my toes and evacuate thirty-six bucks per pound from my credit card — and that was for committing to pretty decent volumes of over a thousand pounds.

For a while, no matter how little quantity we wanted, it was impossible to get a full order. The brewery told me they weren’t even sure what they could get for their own beer, and they had no contract in place for mine. Like so many new waves of extreme (or just more flavorful) brews, most of our new beers used a lot of hops. The guys at the brewery said, “We don’t want to scare you, but you need to be terrified.”

Chanukah came early in 2007 - or, as my people like to say, Christmas came late on the Hebrew calendar that year. I’d been working with my PR guy, Jesse, for about a year at that point. Almost like a one-year anniversary present, we received an inquiry from the nationally broadcast program The Big Idea with Donny Deutsch on CNBC.

Though I’d never seen it, everyone I talked to seemed to know all about it and thought it was clever and fun. The week before Chanukah I shot the producer a follow-up email: What are you doing for the holiday? I think she lived in hyper-producer mode. I’d get three words from a Blackberry.

“Working on it.”

“You available?”

“Hold tight.”

“Dec. 11?”

It turned out the day she wanted me was the day of our eleventh anniversary party at the Toronado. I told them I had to get back in time for the party and they said, “No problem. We’ll fly you out on the red-eye and back that day. We shoot at three p.m. Wear something respectable. No logos.”

Before I went, I had to figure out what the show was. Evidently Donny Deutsch’s father had owned an ad agency that Donny took over. A hotshot kid, he blew it up and made it a widely recognized success. He cashed out of the business and started the show, which featured small business stories from around the country.

One of the guests who was going to be on the same episode with me reigned as the Mattress King of infomercials. A very hospitable guy in person, his business was grossing $800 million every year, selling mattresses, one at a time, on TV. The show also featured more modest entrepreneurs, like the couple from the Midwest who made sand candles in their garage.

Though I was excited to do the show, it proved to be a profoundly disturbing experience. By coincidence, I bumped into a guy at the airport bar who said, “Hey, aren’t you going to be on Donny Deutsch?” He was scheduled for the same show — he owned a guitar-pick company in the Central Valley. Talking to him relaxed me a bit; I found myself uncharacteristically nervous.

The car service picked me up from the corporate hotel where we were being put up during the day and brought me to the studio that afternoon. I was thrown into the makeup room with a couple of hotties, who tried to make me look acceptable for TV. It was the end of the Jewish holiday season. I’m sure I looked pretty damn tired. They coated my entire face with heavy brown foundation, then started recreating it from scratch, with a spray gun and wands of colors and creams.

So it was myself, the guitar-pick guy, and the mattress king. I was going to be on a segment called “Is This the Big Idea?” In it, the featured guests and Donny would discuss the idea of my business, and whether or not they felt it was a Million Dollar Idea. Very quickly (even for television), they go over some basic information about the business — gross sales, the business model, some information about the product, a little bit of past PR. They critique it, and then they give their “informed” judgment.

Meanwhile, the actual businessperson gets about nine words by way of introduction. The whole segment lasts maybe three minutes. I’m used to spouting off with the shotgun approach, usually with print writers, or even radio. You banter a bit, and eventually the right stuff will come out. I’d watched the last two guests, who got time for two quick sentences to define their life’s work.

Still, before we cut the segment, I thought it sounded like an amazing opportunity. Donny had just been in a very public pissing match with Ann Coulter, who was notorious for her “slash and burn” punditry. She’d been quoted as saying something to the effect that it would be a better world if everyone were Christian and Republican. When she went on his show, Donny called her on it. She’d said essentially that evangelical Christianity taught that Christians were “perfected” Jews, and she suggested that Donny give up Judaism and come to church with her. He was furious, and vehemently stood up to her.

Three weeks later, the whole episode was still coming up daily on media segments and blogs. I thought, well, perfect Chanukah present for us to chat about on national TV.

But I got to the set, and it was clear from the start that we were all just preprocessed fodder for the show. I could have been a guy selling garbage cans in New Jersey. There was nothing authentic about the moment or the content. It just filled the time.

I walked in, and the host didn’t even look up. I didn’t need a big hug and a “Hey, thanks for coming across the country on such short notice, in the middle of your busiest sales push of the year.” But some vaguely human gesture would have been appreciated.

I mumbled something about hoping to say happy Chanukah to my mom, and he said, “Yeah, fine.”

We ran through the segment, and it was eleven years of my life condensed into about eight seconds of me, and then these two guys and Donny. To his credit, the owner of the guitar-pick company did a great job of plugging for me, mentioning the high quality of the beers and pointing out how many awards we’d won. But they all agreed that He’brew would never be a million-dollar idea. They said, “You can’t make a product for such a niche market. You’ve got to expand your focus. If you want to make this beer, make it for everyone.”

Ironically, by the end of 2007 we would sell $875,000 of He’brew for the year. So the “million-dollar idea” we were apparently never going to hit on was already pretty fucking within reach.

My friends who were watching said they could see me steaming. I did force my way into a couple of exchanges. I argued, Well, you don’t need to be Irish to drink Guinness, and I slapped Donny on the back and made a wisecrack about him being my bar mitzvah boy. In the end, I was at least given a moment to wish my mom a happy Chanukah.

PR-wise, it was such an eye-opener. Jesse and I are constantly talking about trying to get on wider-audience TV shows such as this one. I specifically remember sitting up in bed with Tracy when we first started, thinking He’brew could surely get featured on Letterman. Leno, Oprah, The Daily Show — what better product are they going to bring out for Chanukah, or Rosh Hashanah, or Purim?

But it’s astounding how many people saw me on Donny Deutsch. For a while the episode ran in repeats, so my ignominy was saved for posterity.

That week, I saw another episode with a similar segment, a woman whose business had done about a million bucks in 2006. She came on gushing about how much she loved the show and how, inspired by Donny’s advice and enthusiasm, she was going to do a million and a half in ‘07. That’s fifty percent growth — pretty huge.

And Donny said, “Well, that’s great. But you gotta think BIG! Why not shoot for two million, five million, ten million!”

This poor lady was busting her ass to grow her company - her million-dollar company. Apparently it wasn’t enough to think, Wow, this woman is really succeeding. Did her expenses go up too? Net profits? Vacation time? Benefits for staff or investments for the future? Evidently, you just need to sell more and more. The why? is never addressed on the show. Are you going to work harder just to accomplish the same thing?

The year after I was on the show, we grew eighty percent. I made a little more and spent a lot more, building a foundation for the next phase of growth.

This guy was so blind to people’s real lives. In my opinion, it’s not about making a million dollars if it doesn’t make your life better, more dynamic, more interesting, if it doesn’t bring something better into your world. Let’s be honest: very often, work kinda sucks. Work is not the payback — it’s the pay. Donny Deutsch should have been celebrating this woman’s hard-won success. Instead, he was ranting about an abstract number.

Art should be for art’s sake, but money needs to be for something different. Something specific. Something meaningful. Something morally sound. Something worth earning.

I flew back to San Francisco that night, missed the party, but arrived for a couple of beers with Zak at midnight. Despite the vote of no confidence from Donny Deutsch, I believed we were onto something special. A few remaining friends and the Toronado beer posse were a better jury anyway.

Before soaking in my self-satisfied bowl of cherries, though, I pulled one last bonehead move for the holidays. Prior to hiring Darren, I’d hired a beer industry friend as my sales rep in the south who had clearly not worked out. I’d been struggling with the frustration through the last three months of the year. By the end of December, I was just burned out on the situation.

I worked myself into a frenzy, convincing myself that I needed to fire her immediately. Instead of taking a deep breath and waiting until the holidays were over, one night I wrote an email about how disturbed and upset I was. I told her I had to fire her. I hit “send” and walked to the shower. The momentary hot-water relief was shattered by a realization: It was Christmas Eve. She was half-Jewish, and I knew she celebrated Christmas with her significant other, her friends and family, even some work acquaintances.

I was overcome with a sickening sense of self-loathing. I wanted to crawl into the Internet and somehow get that email back.

Luckily, she managed to find a new job quickly, and we’ve remained friends from afar. I know we wish each other the best. But that doesn’t excuse my utter lack of judgment and my behavior. One more suggestion to do as I say, not as I did.

When the New Year began, all I could see was the black cloud of the hop crisis growing larger and darker. Paul, the head brewer, and I were on the phone pretty much all the time, emailing, calling, begging, and pleading with anyone who could find us some hops. Yet again, I had to inflate my credit card debt to stay afloat. I also hit up my mishpocha: Peter loaned me twenty-five grand, my mom cobbled together ten thousand, another friend offered fifteen more.

Paul was an absolute lifesaver. He worked overtime to help me keep in constant contact with the hop suppliers, desperately searching for anything that might become available. Through his contacts we eventually found half the hops we needed to keep brewing.

We were paying between five and ten times the cost, and we had to buy it all up front, something that was totally unheard of previously. Cascade, the mother of all Pacific Northwest hops, went from three to four dollars a pound to twenty, to thirty-six. All the other varieties we used across the brewing board went to eighteen, then twenty-four and up.

I got some very kind responses from several brewers I’d become friendly with over the years, including Brian at Dogfish Head, Matt from Magic Hat, and Jeff, the “Chief” at Ithaca. My buddy Brian, who was managing brewing for Spanish Peaks, did me a huge favor in the form of nearly five hundred pounds of Crystal. Still, what we got was nowhere near the many thousands of pounds I’d need.

After months of nail-biting and wrangling, Paul finally secured what became known as the “supplemental hop” purchase: sixty-five thousand dollars worth of hops that nine months before would have cost about nine grand — a few boxes of this, a few boxes of that, a load of insanely priced Cascade, and some other crucial varieties. I remember so clearly a very tense call with the brewery C.E.O., who gave me the final dollar amount while suggesting I should simply not go through with it — not introduce new products and stay smaller, for now.

But I really had no option. If we didn’t make this beer, we wouldn’t hit my projections. I’d already hired Darren, whose wife was pregnant with his boy Kane. Matt’s wife had just given birth to their first baby, Lillia, and at the moment he was the family breadwinner. Zak, Angela, and Jesse had all put their trust and labor toward the company, and toward me. I remember so clearly being on that call, outside a bar in Athens, Georgia, during a lunch stop on a ride-with the first time I visited Darren to get him started with Shmaltz. There was no choice. It simply had to happen.

So many voices pay so much lip service to the “market” in this country. We believe it will take care of everything. The saddest part about the whole disaster was that, in hindsight, it doesn’t look as though it needed to happen at all. There were clearly just enough hops to go around for a year or so. The following year there were even more, and now this year there are plenty for everyone — and hop prices have dropped fifty to seventy-five percent, with futures back down to prices from before the crisis occurred.

Of the fifteen hundred small breweries in the U.S., there were very few, if any, reports of people going out of business because of this enormous calamity. The people who could least afford the massive hit — the small guys who had not negotiated long-term contracts — had to severely limit the hops they used, change the recipes of some of their most important brands, and swallow the crazy price increases. People lost a huge amount of money.

With the panic, the uncertainty, and the lack of meaningful information from anyone who really should have known the situation, I desperately bought anything I could get my hands on, regardless of price. Perhaps I should have rolled even more risky dice and waited it out. Unlike one hop supplier who looks to have taken maximum advantage of the situation, thankfully, my primary vendor, who fought to get me enough to survive without gouging the little guys, literally saved my business. I’ve since signed a long-term contract, securing a big chunk of our future needs at much more reasonable prices.

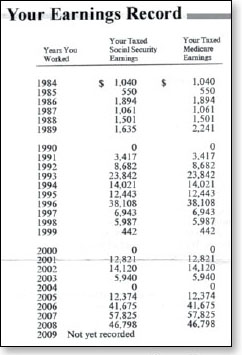

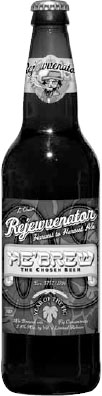

All said, however, in those two years of price insanity I lost almost $200,000. And that was just my little forty-five-hundred-barrel operation at the time, which grew to six thousand barrels by the time the crisis was on its back slope. Two hundred grand — and you’ve seen my Social Security statement. Many others must have lost much more.

The financial rules of the beer world have been set by much bigger companies than ours — much bigger, in fact, than even the biggest craft brewers. If a craft brewer is buying anything, from bottle caps to glass, paying for trucking, brewing equipment, or raw ingredients, the logic is set on a much bigger scale. Though not an M.B.A., I do understand the concept of economies of scale.

But for an industry as vibrant and multi-dimensional as the over-fifteen-hundred small brewers in the country selling an estimated $3.5 billion of product, it’s shocking to realize how few options — how few suppliers — really control the vast majority of materials needed to run this industry. Trying to scale that supply chain down to craft beer on the artisan side, the numbers barely make any sense.

Admittedly, I made a ton of bad decisions along the way. But even without a brewery and other overhead common to the industry, it took me nearly ten years to start making any profit — and what profit there is has been rather modest. From conversations with many fellow brewers — many of your and my favorite brands — this is not uncommon. That is one hell of a lot of risk and investment and labor with which to pursue one’s passions in a for-profit venture.

Still in the throes of survival mode, while reeling from the monster expense of the hop crisis, we amazingly managed to keep production rolling and barrel through to hit my “aggressive” sales targets from Eva’s master Excel file. Coming to the company with varying professional experience but a similar disposition for obsessive commitment, both Zak and Darren grew into their roles and responsibilities as regional sales managers in very different ways — but both to hard-earned stellar success. Their distributors were up big numbers, many well over one hundred percent. After my poor record of retaining past co-workers, I was relieved, then thrilled, that these guys threw themselves into the job with such vigor and focus. I have repeatedly told them I want them both to be so much better at the job than I ever was — and they seem to be working their asses off to make my demands come true.

The Coney success in New York City helped our overall growth significantly, and we somehow managed to pull through the shit-storm building stronger relationships, more excitement about our products, and a core team of over achieving staff. This seemingly basic idea — that if we simply had the ingredients to make more beer and the zealous staff that could push the hell out of it — was actually happening. By 2008, we were doing a little over $1.5 million in sales — still small, but up ten times what it had been just five year before. In 2009 we’d hit just shy of $2 million, and 2010 is looking like a similar trajectory. In my mind, at least, I can hear Donny Deutsch hollering, “I don’t care what the sales are. It’s still not a million dollar idea!”

It was finally time to roll out our first summer seasonal from He’brew: Rejewvenator. Originally, I’d planned to release it for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. (As the Los Angeles Times had riffed so many years before about He’brew, “This beer could give new meaning to the term ‘High Holidays.’”) But instead of creating an entire new release in such a short time period before our fall-release Jewbelation, I realized we could flip seasons between two beers by releasing Rejewvenator in spring and running it through the autumn High Holidays instead.

The seal for the deal came in the form a letter from a lawyer representing, of all people, Sierra Nevada Brewing Company, many months before our Rejewvenator was even planned to launch. With very uncharacteristic planning, Matt and I had already just about finished the label the year before. We’d printed an advance description with a tiny, mocked-up product shot, along with the rest of our lineup, on our small promo postcards, which we handed out at beer fests and other events. This was the only place the information appeared. I’d told Matt we needed a small secondary descriptor for Rejewvenator, a tidbit to clarify the seasonal as an alternative to Jewbelation, which we called our Anniversary Ale. I threw out the line “Annual Celebration Ale,” and he slapped it down.

Yes, of course I knew about Celebration Ale from Sierra Nevada. It had always been one of my favorite special releases, another “extreme” beer far ahead of its time. But the word celebration seems to be ubiquitous when it comes to beer-related fun. There’s Celebrator beer from Ayinger and Celebrator Beer News and… Honestly, it just never occurred to me.

The law firm representing Sierra clearly did not agree. “Dear Mr. Cowan: It has come to our attention… ipso facto… whereas aforementioned to the extent that… blah, blah, blah… Cease and Desist Now.”

I was shocked. Sierra Nevada? Couldn’t they have just sent an email? A quick note from the brewery — “Hey, wondering about this postcard we saw. How about we trade you a name change for a case of Celebration for Chanukah?” I would have been happy to oblige.

Instead, I got this series of aggressive and intimidating legalese missives, on expensive swanky law-firm linen paper, no less.

Late one night, I banged out an extraordinarily sarcastic response I thought I would send Sierra management and the beer media. But then, in an unusual show of restraint, I realized I’d better just shut up and change the name. Harvest to Harvest Ale, it is. No one’s trademarking that, gents.

Perhaps I should be grateful that the lawyer saved my shtick. Suddenly it all came together. From the label — “Jewish tradition celebrates two New Years: The first calendar month in Spring historically comes after the barley harvest. The High Holidays in Fall mark the creation of the world. Harvest to harvest — the perfect bookends for deliciousness!”

The mirroring of the new years, this doubling effect of the seasons, stirred my question to Paul: Could we use two yeast strains, a lager and an ale?

From the label of Rejewvenator Year of the Fig, 2008:

“The winter of bondage has passed, the deluge of suffering is gone,

the Fig tree has formed its first fruits, declaring all ready for libation.”

- Song of Solomon

Jewish tradition celebrates 2 New Years: The 1st calendar month in Spring historically came after the barley harvest. The High Holidays in Fall mark the creation of the world. Harvest to harvest - the perfect bookends for deliciousness! Arise noble Rejewvenator, infused for ‘08 with the sacred succulent Fig. O the history, O the shtick: Gen 3:7: “And their eyes were opened, and they knew that they were naked; they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons.” Time to get cooking! “Professed Wrestlers and Champions were in times past fed with figs.” -Pliny, Roman naturalist. Romulus, mythic founder of Rome, and his twin Remus were nursed by a wild she-wolf under a fig tree. In 1857, Queen Victoria commissioned an 18 inch plaster fig leaf to adorn her cast of Michelangelo’s David. “The statue that advertises its modesty with a fig leaf brings its modesty under suspicion.” -Mark Twain. Buddha gained enlightenment meditating beneath a fig tree. Zechariah/Micah: “Nations shall beat their swords into plowshares…all will sit with his neighbor under his fig tree, with no one to be afraid.” Fear not Shmaltzers - Grab your Newtons, rub your happy belly, strap on your fig leaf and your championship belt, and prepare to blow your shofar…tis a new HE’BREW Beer season to rejoice. L’Chaim!

I’ve always been a fan of malty, dark beers, with the thematically appropriate names doppelbock (often called “liquid bread,” a rich lager to help the German monks get through Lent) and Belgian dubbel (or double, a classic monastic strong brown ale). Why not pinch from acclaimed, sacred European brewing tradition to create some new Jewish brewing history, and an only-in-America craft beer?

The “-ator” ending for all beers in the style comes from the original doppelbock, Salvator, or savior, with its obvious religious connotations. We already had the He’brew Messiah, so it would be the Rejewvenator to begin the new year after Passover in the spring — liberated from bondage and ready to indulge in chametz (leavened or fermented grain, i.e., beer), which is forbidden till after the holiday.

The totem animal of the doppelbock style is a goat, usually with large horns reminiscent of (and genetically related) to the ram, which appears in Jewish text as the substitute for Isaac in Abraham’s near-sacrifice of his only son. The story of the binding of Isaac is read every year for Rosh Hashanah, when the ram’s horn, or shofar, blasts its annual spiritual wake-up call to the congregation. The shofar also looks a little like a small beer bong.

In keeping with the sacred species theme, Angela had sourced an exquisite fig concentrate, pressed straight from luscious mission figs near Indio, CA. I’d had the salesman’s contact information scribbled in a margin of an email buried in a folder. I sent him an note and didn’t hear back. I sent him another — no answer.

Suddenly we were only six weeks away from brewing the beer. I called the supplier and he said, “Sorry. I changed my email address.” One other thing: he could no longer get the concentrate.

We all started making desperate phone calls, and I soon reached a very cordial older gentleman grower, a broker in upstate New York. He informed me there apparently had been a “fig crisis” the year before, and there would be no fig juice until next harvest in the fall. I respectfully replied, Sir, the word “crisis” is currently reserved for hops. You’ll need to find a suitable substitution, such as catastrophe or apocalypse.

Miraculously (I don’t know how he does it), Paul called a company in California’s Central Valley and managed to procure the exact fig concentrate that we’d previously sourced. They’d already told us they were completely sold out, but Paul charmed them into selling us two fifty-five-gallon drums. Bob sent a truck, and they arrived three days before we were scheduled to brew.

The Rejewvenator series is now one of my favorite beer projects that we make. In 2008, it was the year of the fig. The following year was the year of the date, which was recently awarded a gold medal at the World Beer Championships. For 2010 it’s the bubbe of all sacred Jewish fruits, the Concord grape.

That leaves one sacred species we haven’t used yet — olives. Oily, and not even vaguely a flavor to pair with any beer we’ve thought of lately, olives will be a serious brewing challenge for everyone involved in the next round of Rejewvenator, slated for 2012. The fruit of the branch brought to Noah by that innocent dove, who never imagined how complicated she would make the lives of a handful of brewers trying to create a unique beer recipe with a product that is seemingly unusable in the brewing process: This is what it sounds like, when the brewers for contract-brewers cry…