CHAPTER 4

COLD WARRIOR

When Roy joined the Texas National Guard at the age of sixteen, he stood only five feet six inches tall and weighed 129 pounds. He was no one’s idea of a model soldier. But soon Roy was folded into the ranks of the millions of American men and women charged with maintaining combat readiness during the early stages of a burgeoning global Cold War. Roy joined the military at a time when the entire planet seemed on the edge of conflict. As a colonel in the Texas National Guard forewarned, “The United States is on the verge of a crisis. We must face the facts, no matter how brutal. All Americans must prepare for service.”1

In fact, America was already at war. When Roy signed up in 1952, American soldiers were fighting in Korea to prevent the spread of communism in Asia. The United States committed troops to Korea based largely on the “domino theory,” the widely accepted belief that developing countries, especially in Asia, could fall one by one like a line of dominoes to the influence of communism. A communist revolution in one country, American statesmen warned, would embolden communist revolutionaries in the next, and so on. To prevent such a communist wave, the United States in the 1950s embraced the approach of “containment” that called for American forces to stop the spread of communism nearly anywhere in the world. This foreign policy was guided by a lesson from World War II, that the United States must never again allow a potential adversary to gain control of such a vast wealth of resources in Europe and Asia as did the Nazis and Japanese Empire in the 1930s. Communism, insisted American leaders, would not be allowed to spread as had fascism in the 1930s.2

Roy was mustered into the Headquarters and Service Company of the 136th Heavy Tank Battalion, a unit of 156 men out of El Campo. His three-year commitment would begin with training in basic military skills including fitness and weaponry. After this initial training, he would be responsible for appearing in uniform one weekend per month and two weeks every summer to maintain his skills. For this, he was paid a few dollars per training session, increasing with his rank. The other benefit was that he would not be eligible for the draft when he turned eighteen, fourteen months after his initial enlistment.3

Roy was assigned to basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky. While many cadets agonized over boot camp, Roy made light of the training by comparing it to the difficult experiences of his childhood. “It reminded me of being back in the labor camps of my youth, only easier,” he wrote. “I never could figure out what a lot of the other guys were complaining about. We ate good, most nights we slept under a roof, only one to a bed, and we got a lot of exercise.” The conditions were likely more challenging than Roy later let on. The previous year, military inspectors at Fort Knox had reported “low morale” and a “deplorable situation.” Still, perhaps his timing was the most fortunate factor. Either way, Roy had a point about getting to sleep in his own bed, a luxury he didn’t always enjoy during his time as a migratory laborer.4

Roy liked the National Guard. Always outgoing, he enjoyed meeting new people and hearing stories of their lives. He was glad that his fellow soldiers came from “a variety of backgrounds” and “worked together as a team,” he wrote. Such diversity helped show Roy that cooperation between people of different races was possible. “It opened my eyes to the opportunities for a half-Mexican, half-Indian dropout from South Texas,” he remembered.5

Roy did well in the Guard. He completed boot camp and earned promotion to corporal, giving him a little extra pay and a sense of accomplishment. The promotion was his first notable achievement in life, and he was excited to come home to tell Uncle Nicholas. The boy who had known only rejection and disadvantage was proud of his success. “I was really starting to feel good about myself,” he explained.6

Initially, the Guard was only a small part of his life. When he wasn’t training with the Guard, Roy worked at the auto shop. He was earning about fifty-five dollars per week, nearly twice the average weekly income for workers in Texas at that time. The job was challenging, not just in terms of labor but also intellectually. Roy’s boss and mentor, Art Haddock, was continuously pushing him to dream of more. Roy listened. The boy who had lost his father at such a young age was still impressionable, especially when it came to older men who paid him attention, and he respected and responded to Haddock’s guidance. Haddock pointed out that Roy’s peers by then were graduating high school and starting their careers. “This is not a bad job,” Roy remembered Haddock saying, “but is it going to be a good job for you when you’re twenty-nine or thirty-nine?” Roy wrestled with this question.7

Those were good years. Roy began feeling a new sense of optimism about his future. At one point, he was fortunate to meet Audie Murphy, the legendary World War II hero and movie star who had joined the Texas National Guard two years before Roy. Roy had seen Murphy’s biographic film, To Hell and Back, a dozen times by his count. He was drawn to Murphy because they were both undersized, poor Texas kids who had grown up picking cotton. Roy admired Murphy’s life story and appreciated that the famed hero “talked to us as if we were his buddies.” “Audie Murphy became my idol and role model,” he wrote. His appreciation for the military and its soldiers deepened as he experienced life in the Guard. The military provided structure and clearly defined values of courage and integrity. Hungry for direction, Roy soaked it in.8

It was not all serious. Roy shared some funny memories of various gaffes during his time in the Guard. One day he came down with a bad case of diarrhea while driving a superior to a meeting. The ailment kept forcing Roy to pull off the road and scramble behind some bushes to squat. After a few such stops, the lieutenant colonel lost patience and jumped behind the wheel, speeding off as Roy was defecating on the side of the road. But Roy had forgotten to check the gas gauge, so the officer didn’t get very far before having to walk himself.9

Roy still carried what he called “a bad attitude” that sometimes exploded in overreactions to perceived slights. “If I thought some guy was looking down at me,” he remembered, “I’d try to put him down on the ground so I’d be looking down at him.” Such an attitude, combined with his “smart mouth” and penchant for goofing off, got him in trouble a couple of times. He twice lost his corporal stripes for minor infractions and had to earn them back. But for the most part, he was a pretty good soldier. One of the guys who enlisted with Roy remembered him as “a little hard to manage, but generally an excellent soldier with much pride in himself, his unit and his country.”10

Roy stayed in the Guard until May of 1955 when he was nineteen years old. During his time in the Guard, some of his fellow guardsmen would talk about the possibility of joining the regular Army. It was a heavy topic, considering that tensions between the global superpowers appeared as if they could burst into conflict at any moment. Increasing numbers of American soldiers were stationed across the globe, the first line of defense in a worldwide struggle against communism. Anyone who joined the Army in the 1950s understood that there was a good chance of seeing action.

The idea of joining the Army appealed to Roy’s sense of adventure and toughness. He could see the world, his friends said, and he could help defend America from those who wished for her demise. One day, Roy’s buddies insisted, he would be able to tell his grandkids about his incredible adventures. “The recruiters omitted some of the less glamorous aspects…,” Roy remembered, “but they convinced me that I wanted to be army and to be a special part of it.”11

As Roy considered the Army, he imagined the possibilities of a future spent in El Campo. All he could see in that future was a life working in the fields or the tire shop, and an existence polluted by the same racial epithets and disadvantages that framed his early life. “What was there for me if I spent the rest of my life in El Campo?” he thought. “Just another poor Mexican in a small Texas town full of them.” The Army offered an escape from the deepest depths of a difficult youth.12

Roy was leaning toward enlisting, but he felt that he couldn’t make a final decision without the approval of Uncle Nicholas. One day, the pair sat down in the family living room to talk about the possibility of Roy joining the United States Army. It was a heavy conversation. Roy remembered Nicholas telling him, “I believe that the Guard has done a lot to increase your confidence in yourself; and I think that it has begun to teach you a sense of responsibility; but I want you to be certain that this is what you want to do.” Roy listened carefully to the man who had raised him. He had thought a great deal about the level of commitment the Army demanded and what it could mean for his life. Roy told Nicholas that he was sure he wanted the military to be his future. A pang of emotion passed between the men. Nicholas’s voice cracked when he said, “I’m very proud of you.” Roy was going to join the Army, taking a potentially dangerous path in a frightening world.13

Roy rode a bus more than seventy miles to the military entrance processing station in downtown Houston. He entered the old United States Custom House at 701 San Jacinto Street, a gray, three-story office building where Muhammad Ali would famously refuse military induction twelve years later. Roy walked up the steps and looked for the Army desk, crossing “that creaky old wooden floor and [feeling] as if I were running a gauntlet.” He described himself approaching the Army recruiter “like a cocky little rooster with all of my papers from the Guard and all of my records tucked under my arm.”14

Roy’s Army career officially began on May 17, 1955. He signed up for a three-year enlistment, starting at the rate of $86.80 per month. He was allowed to leave the Texas National Guard a month early because he was enlisting in the United States Army. He swore an oath to serve the United States “honestly and faithfully against all their enemies whomsoever.” His National Guard experience did not count toward his new rank in the Army. He began again at the rank of private, meaning he was not eligible to start an advanced program such as infantry school or airborne training. He had to do basic training again.15

By the time Roy joined the Army, the Cold War had dramatically shifted. From the United States perspective, the Korean War had ended. Both regimes survived the conflict, leaving no clear winner. North and South Korea remained separate, divided at the very same 38th parallel established at the end of World War II. The war was incredibly costly. In just over three years, thirty-six thousand American troops had died. South Korea was left mired in devastating poverty, while North Korea was almost completely leveled by American bombing. But communism had been contained to the North. Although this one domino had not fallen, the United States committed to maintaining a massive troop presence in South Korea to help stave off any further potential threats.16

Meanwhile, another major crisis was developing in the wake of France’s defeat by communist forces in Vietnam. Since the 1880s, the French had held and managed the colony known as French Indochina, a territory that included modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. For decades, France profited from Indochina by exploiting the region’s resources and laborers. This control began to waver in 1940 when the Vichy government of France granted Japanese access to Vietnamese territory during World War II. The ensuing years were catastrophic for many Vietnamese citizens as Japan’s war machine consumed many of their people and supplies. French and Japanese food policies during World War II led to a famine that killed as many as two million Vietnamese citizens.17

During those catastrophic years, a small nationalist group known as the Viet Minh began to appeal to the masses. They helped poor, starving peasants capture and distribute rice from storage sheds. They also recruited Vietnamese to a cause rooted in communist liberation ideology, promising to lead a renewed revolutionary struggle after the war to overthrow the imperial powers and establish an independent Vietnamese nation.18

The Viet Minh were led by Ho Chi Minh, a longtime anti-colonialist who for decades had dreamed of Vietnamese sovereignty. Minh had been active in this cause since the 1910s. In 1920, he told an audience of French socialists, “We have not only been oppressed and exploited shamelessly, but also tortured and poisoned pitilessly.” “We have neither freedom of press nor freedom of speech,” he testified. “Thousands of Vietnamese have been led to a slow death or massacred to protect other people’s interests.” By the early 1930s, Ho Chi Minh was openly calling for revolution, insisting, “If the French imperialists think that they can suppress the Vietnamese revolution by means of terrorist acts, they are utterly mistaken.”19

The opportunity for that revolution finally emerged with the end of World War II. In September of 1945, within hours of Japan’s formal surrender to the United States, Viet Minh leaders declared independence from France. In doing so, they borrowed directly from language in the United States Declaration of Independence, invoking the storied phrases of a powerful nation that had once fought its own revolution to win sovereignty from a colonial power. “All men are created equal,” the Vietnamese declaration similarly read, “they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” In another speech later that autumn, Ho Chi Minh cited the language of the Allies in World War II. “Not only is our act in line with the Atlantic and San Francisco Charters, solemnly proclaimed by the Allies,” he argued, “but it entirely conforms with the glorious principles upheld by the French people.” Vietnamese nationalists hoped for American support by appealing to the creed of the United States and the stated principles of the victorious Allies who had just won a global war in the name of democracy and self-determination.20

But the French wanted their colony back. When the Viet Minh organized to resist, the United States backed the French. As it turned out, America’s foreign policy did not align with its global rhetoric of self-determination when the people fighting for freedom were socialists or communists. And so began a long war between Vietnamese liberation forces and a French military aided by the United States. The French lost that war in 1954, with peace established by an agreement to split Vietnam into two, North and South, and a plan for later elections that would unify the nation under one government. Ho Chi Minh’s party was heavily expected to win that vote. By the time Roy joined the Army, the United States was staring down the possibility of a united communist Vietnam, thus triggering fears of the domino theory and the spread of communism across Asia.21

Before Roy left for Army basic training, his family threw him a going-away party. Roy was warmed by his family’s send-off. These were the people who had taken him in and raised him as their own, and he was forever grateful for their love. He later reflected, “I was too immature at the time to understand the pride that people of my culture take when a member of their family chooses to serve our country.”22

Roy boarded a train headed for Fort Ord near Monterey, California. He was taking a big step, venturing out into the world. He had never been to the West Coast and was “excited” for the “adventure.” The three-day trip also gave the nineteen-year-old time to reflect. He replayed memories of other trips in his life, and he thought about the people who had shaped his journey to that point. The train was packed with other enlistees and officers, charged with “herd[ing] us like cattle,” he wrote, “through the dining cars and the stops and stations along the way.” Roy noticed that most of the other recruits had very different expectations for the Army. The other young men talked about its temporality, expecting “two or three years” in the service before leaving to cash in on the GI Bill by going to college or starting a business.23

Roy was different. He already knew that he would be in the Army for the foreseeable future. He couldn’t go to college; he hadn’t even finished ninth grade. The Army was going to be his life. He was banking on a long career in the military, one that would provide a secure job, bring pride to his family, and help give him a sense of belonging in a nation that offered limited opportunities. “I saw it,” he wrote, “as my single chance to be successful. If I was not, I knew I could never look Uncle Nicholas in the eyes again.”24

At basic training, the drill sergeants prepared the men for combat. They were “pretty tough characters,” Roy recalled of the battle-tested instructors, many of whom were veterans of World War II and/or Korea. At that time, the United States was not officially at war, but the possibility of military intervention loomed over every new enlistee. It was still the nascent days of the Cold War, when the world seemed likely to crack open at the slightest provocation. These new recruits needed to be ready to fight anywhere on the globe, and they were trained with the seriousness and urgency of men headed off to war.25

Roy’s basic training included lessons in weapons, aptitude, and discipline. He and the other enlistees spent hours learning how to use their service rifles, taking them apart and reassembling them over and over again. They were also instructed in the use of machine guns, mortars, and a variety of other combat weapons. Teamwork and military discipline were drilled into the cadets through an endless array of exercises and inspections. The men were challenged physically and mentally. They ran hills and did push-ups, preparing their bodies and minds for combat. “I was trained as a warrior,” Roy said.26

The seasoned soldiers picked and prodded the new enlistees, which didn’t always bode well for the short-tempered teenager from South Texas. One drill sergeant made fun of Roy’s given name of Raul, the name he was given at birth and under which he was baptized. This drill sergeant mocked the name, drawling it out—“Ra-oooool”—in a loud, mocking yell. Roy hated the teasing nature of the sergeant’s pronunciation. Afterward, he made sure the name Roy, not Raul, appeared on every bit of his paperwork and was used in introductions.27

Roy also had a dispute with a cook who routinely picked on him. Roy at one point hit the guy, causing him to fall on a hot grill. “The drill sergeant chewed me up one side and down the other,” Roy remembered of the incident. He also had a “few scrapes,” Roy noted, off base. One evening he got into trouble when he and a buddy got lost in the dark during a night maneuver. Roy and the other soldier were trying to take a shortcut across some fields when they were sprayed by a couple of skunks. The men were ordered to strip off and burn their clothes while their comrades howled with laughter. The pair was then ordered to march to the football field where they slept all night naked in the cold. It was funny in hindsight; “I’ve had a grudge against skunks ever since,” Roy later quipped.28

Roy spent two months at Fort Ord before moving on to advanced infantry training at Fort Carson near Colorado Springs, his first time back in the state since he was a kid picking sugar beets. This next stage of training began on his twentieth birthday. At Fort Carson, Roy was able to enter a classroom again, where he relished the opportunity to become a good student, unlike the public school experiences of his youth where he remembered having “felt like a dumb ‘Mezikin’ kid who wasn’t expected to do more than take up a chair.” He’d never had a chance to do well in school before because his family’s migratory farmwork stole so much of his academic year. In the Army, he was able to sit for all the classes just like everyone else. “I discovered what a real kick it was,” he remembered, “to sit in the front of the class and have the first answer rather than to hide in the back and hope I didn’t get called on.”29

At Fort Carson, Roy had the pleasure of watching a famous athlete excel at his craft. Billy Martin, the New York Yankees second baseman and Most Valuable Player of the 1953 World Series, had been drafted into the Army in 1954. His training at Fort Carson overlapped with Roy’s for about a month. Martin had a terrific career in baseball, winning four World Series titles as a player and another as a manager. One of his peers later called him “the most brilliant manager I ever saw.” In the summer of 1955, that talent was employed as the player-manager of a ball club at Fort Carson, where he led a squad of cadets to a championship season. Reporters were all over the place, following Martin’s exploits before the major leaguer returned to the Yankees later that season to help Mickey Mantle and the rest of the Bronx Bombers capture the American League pennant. Roy had some interesting ball games to watch during his recreational time.30

After nearly two months of training at Fort Carson, Roy received orders sending him to Korea, his first overseas assignment. But first he had a chance to visit El Campo. He took a bus over five hundred miles from Fort Carson to El Paso where he transferred to another bus that carried him more than six hundred additional miles to Cuero, the place where he was born. Roy wanted to see his half-sister, Lupe, who was just thirteen at the time. After a brief visit with her, Roy returned to El Campo a much different man than the nineteen-year-old who had left for the Army less than five months before.31

When Roy exited the bus, he saw the cab driver he used to work for as a translator. Roy’s family had not known exactly when he would arrive, so no one was waiting for him at the station. But his old cabbie friend gave Roy a ride to Uncle Nicholas’s sheriff’s office. Roy walked in and waited for his uncle. When Nicholas entered a few moments later, the sheriff stopped in the doorway and stared at his nephew. Roy remembered Nicholas’s expression as “unsmiling but happy.” Roy knew that he looked different. Men who go to basic training as teens come home with broader shoulders, thicker chests, and sharp haircuts, appearing as if they’ve made a transition from postpubescent adolescents into grown adult men. As Nicholas looked him over, Roy thought he could sense his uncle swelling with pride. For Roy, making Uncle Nicholas proud was perhaps the most important thing in the world. He was no longer the skinny punk who fought other kids in the streets. “Seeing him look at me that way,” Roy later wrote of the moment, “made any discomfort I had endured during training completely worthwhile.” They shook hands and went home.32

Roy was able to spend about two weeks with his family. Those were good times. The entire clan would gather around Roy to listen to his stories of Army adventures in California and Colorado. Even Grandpa Salvador, the old storyteller himself, “begged me to tell them about my experiences.” They assembled around Roy just like Roy and his cousins had once congregated around Salvador. Roy had become a point of pride in their family. He believed in himself and what he was doing. “People were looking up at me,” he described, “without my having to knock anybody down first.” The time with his family made Roy think deeply about his life. “God had given me a ‘song in the night,’” he wrote, referencing one of the old ballads his father had sung, “after I had lost my father and mother.”33

When his time at home ended, Roy traveled to Seattle where he boarded a boat that took him across the Pacific Ocean. After a weeks-long journey, he joined the 17th Infantry Regiment, a famous unit that was part of the 7th Infantry Division. The 7th Infantry had been in the thick of fighting during the Korean War, having suffered more than fifteen thousand casualties. When Roy arrived, the unit was stationed at Camp Casey, between Seoul and the 38th parallel. As Roy wrote, “the real shooting war had just ended” by the time he arrived. Thankfully, the roughly sixteen months he spent in Korea were mostly peaceful, yet nevertheless transformative.34

Roy had two primary impressions of his time in Korea. The first was that he was no longer so much shorter than everyone else. “I stood taller than most Koreans,” he remembered. “I liked to walk around without having to look up at everybody.” The second observation was more difficult. Roy was struck by the devastating poverty and horrible conditions facing the South Korean people. The locals had been left destitute by the preceding war. Some were literally starving. People would go to trash dumps to find discarded chicken bones that hadn’t been picked completely clean. Others turned to prostitution and theft to feed themselves and their families.35

Roy was no novice to poverty. As the child of Hispanic sharecroppers in Great Depression Texas, he grew up as a member of one of the poorest groups of people in the United States. But Roy’s hard life was unlike anything the twenty-year-old saw in Korea. “The living conditions of the Koreans shocked me profoundly,” he wrote. He described Seoul as a “bombed-out city” and observed that houses in the rural areas were “constructed from the refuse of the army. The roofs were often made of flattened beer cans and pork-and-beans cans.” He remembered the people plucking building materials from the trash heaps and women and children collecting feces out of Army latrines to fertilize their fields.36

Roy also had a tough time with the winters. He had never known cold like in Korea. The men had to “hack foxholes out of that frozen, snow-covered, rocky soil,” he described. The rainy season brought monsoons that created other difficulties. “We squished about our duties wearing wet socks, and most of us developed foot fungus so severe that we thought our toes were going to rot.” “We couldn’t decide which was worse,” Roy wrote in comparing the two extremes.37

Roy was sympathetic toward the Korean people. There were unpleasant cases of robbery and prostitution, but he remembered the local people generously and fondly. He praised those he met as “proud” and “independent.” And he was inspired by their massive, battle-tested army. “The Korean soldiers I worked with were excellent,” he described. Many American GIs stationed in Korea married and had children with Korean women. Some left behind kids, the abandoned offspring serving as “a horrible reminder of the price paid for occupying foreign lands,” Roy wrote. Roy himself formed a relationship with a local Korean boy named Kim. He would pay Kim to run little errands, just like the cowboys of Cuero had once paid Roy.38

Something else happened to Roy in Korea. He learned lessons about duty, honor, and fairness, especially when it came to race. As an active-duty member of the military, he worked alongside men of other races. “Maybe I was a little shorter, or a little darker, or had a different-sounding name from some,” he recalled, “but to the other troops I was just one of them.” The armed forces helped insulate him from racial discrimination. The Army was certainly not free from racism, but its structures, rooted in rank and orders, offered a unique form of equity that Roy had not experienced elsewhere in society. “I felt more a part of something than I ever had,” he wrote. “I was equal.”39

Roy’s time in Korea ended in January of 1957. Upon returning to the United States, he was stationed at Fort Riley in Kansas and then allowed some leave to return to El Campo before his next assignment. While back at home, Roy reconnected with Lala Coy. In 1957, Roy was still only twenty-one years old and Lala just twenty-two. According to Roy, their romance really began to blossom during a lunch break she took from her job at a local clothing store. After that, they began spending as much time together as possible before Roy’s next deployment. But Lala’s family was very strict and required that most of their dates be supervised. They were rarely alone, spending their time among her family or his. Going out with “only one chaperone,” Roy later kidded, pushed the boundaries of propriety. Supervised or not, Roy and Lala established a connection during that short time. “Our feeling for each other was something special,” he wrote of those few days. When Roy received orders for another deployment, they agreed to write letters to each other while he was away.40

In April of 1957, Roy was assigned to Berlin. Like the rest of Germany, Berlin was divided into four spheres by the Potsdam Agreement of 1945. Russia controlled the east, and the United States, England, and France occupied the west. For decades, Berlin served as a proxy for the global struggle between capitalism and communism. It was one of many such locations, but unlike places such as Korea and Vietnam, Berlin was one of the very few sites where Americans and Soviets faced off in direct confrontation, separated by mere feet across a narrow border that was later demarked by the Berlin Wall. With roughly 180,000 United States troops in West Germany and 500,000 Soviet soldiers in East Germany, the occupied nation in the middle of Europe promised to be a site of major conflict if the world’s superpowers ever did declare war. “It was a strange city to be in during the heart of the Cold War,” Roy wrote of Berlin. “There was constant tension…” he recalled. “We were never at ease.”41

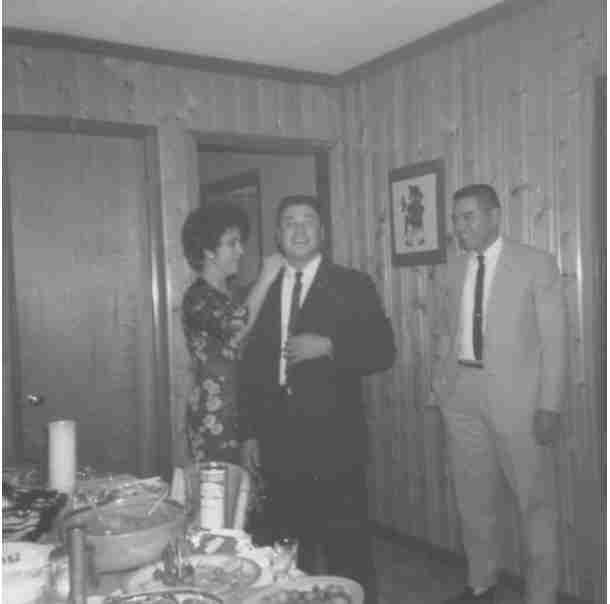

Roy in Germany. Roy P. Benavidez Papers, camh-dob-017318_pub, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

That international tension motivated Roy to become what he called a “model soldier,” joking, “Any misstep of mine was a direct reflection on the entire U.S. Army and could launch World War III.” But he was far from perfect. Roy committed some blunders in Germany while out drinking at night. On one occasion, he claimed to have peeked under a “Scotsman’s kilt” as part of a prank and was punched as retribution. Luckily, Roy quickly realized that he had deserved the blow and dismissed the attack before the conflict could further escalate. On another occasion, Roy was the one throwing punches when he struck a drunken lieutenant who had insulted him. This was a major problem because of rank. Roy was deeply concerned about the consequences, but he was ultimately spared from severe punishment by the mercy of another commanding officer. Once Roy was reported as being absent without leave (AWOL) from his unit from 6:15 p.m. to 2:55 a.m., most likely because he was out drinking with friends. He was docked a rank for that violation, going from Specialist Third Class, a rank he had achieved while in Korea, to Private First Class.42

Despite some setbacks, Roy’s service in Germany resulted in a net positive for his career. In September of 1957, he received a letter of appreciation from a captain for his “display of effort enthusiasm and professional competence.” “Your effort and hard work,” the captain wrote, “reflect great credit upon yourself and your unit.” He also received the Army of Occupation Medal for his time in Berlin, one of many medals to come.43

Perhaps the greatest personal highlight of Roy’s time in Germany was his burgeoning love affair with Lala Coy. “We dated through the mail,” he explained, “carrying on a pretty hot love affair.” Their relationship began to develop greater depth. Roy shared with Lala the frustrations with race and class that had defined his early life. “She understood the hatred and bitterness that caused my fierce temper,” he wrote. “From the first letter I knew that she knew more about me than I knew about myself.” Roy grew increasingly serious about pursuing Lala as a possible wife, and he told Uncle Nicholas about his intentions. Back in El Campo, Nicholas acted on his nephew’s behalf. He visited Lala’s family to request that Roy be allowed to formally court her upon his return home. Lala’s father, influenced by Uncle Nicholas’s stellar reputation, gave his blessing for the relationship to proceed, and the pair continued to write, excited to continue their courtship in person when Roy returned from Germany.44

Lala also came from a working-class Latino family, but there were a few major differences between her and Roy. She wasn’t as wild or angry in her youth, and her calm demeanor was a good influence on Roy. She also had more formal education. While Roy was starting his Army career, Lala graduated with the El Campo High School class of 1955. In high school, she had belonged to Future Homemakers of America, the book club, the garden club, and the school choir. She was a smart, reserved, and hardworking student. After graduation, she took a job at Zlotnik’s clothing store.45

In April of 1958, Roy returned to the United States just as his three-year commitment to the Army was about to end. He arrived at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas just weeks after Elvis Presley had been inducted there and received one of the most famous haircuts in human history. While at Fort Chaffee, Roy underwent a physical examination. He was in excellent health. He had picked up some weight while in the Army and now measured feet five eight inches and 165 pounds. His build was still classified as medium, and his vitals—blood pressure, resting heart rate, vision, and hearing—were all normal or better than average. Overall, the physician who examined Roy deemed his health to be “Excellent.”46

Roy was in great shape, had a steady career, and was falling in love with a woman he admired and respected. He even bought himself a car. His life was becoming ever more promising. He had pulled himself out of the tailspin of trouble that had infected his youth and found purpose through the military, the one place in American society where he finally felt equal. Most importantly, he had gained the admiration of his family, especially Uncle Nicholas. “The year 1958 was a good one for me,” he remembered.47

Roy arrived home from Germany with “an eagerness I had never felt before,” he wrote. He was excited to spend time with Lala and explore the affection growing between the pair. He was twenty-two years old at the time, the same age his father had been when he met Roy’s mother at the Lindenau Rifle Club. Roy brought back from Germany a special gift for Lala, a music box he claimed to be over one hundred years old. The box depicted the Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus and played the song “Ave Maria.” He told her that he would like to give the box to their first child.48

That spring, the young couple began their formal courtship. At first, they attended social functions that were chaperoned. Like many young people in their community, they dated in groups with friends and family, spending little time in private and almost no time alone. “Eventually,” Roy wrote, “we were granted the privilege of being allowed to talk privately on her front porch.” But Lala’s sister would still sit by a window, “watching us lest our hearts begin to rule our heads.”49

Roy was honorably discharged from the Army on June 9, 1958. He officially reenlisted the very next day and signed up for military police training that would take him to Fort Gordon near Augusta, Georgia. By then, he was earning about $160 per month. For the next nine months, he trained as a military policeman. He did well and stayed out of trouble. According to Roy, he finished first in his class but was bumped to second place after ordering some cadets to throw away clothes that other soldiers had left out after a night of partying. Ironically, the wild-teen-turned-disciplinarian was incensed at his fellow soldiers for goofing off and neglecting protocol. He, too, still liked to have fun, but he took military duties extremely seriously. But punishing these men by tossing out their property went a bit too far. “I was still working on that temper of mine,” Roy explained.50

Roy at Fort Gordon, May 1959. Courtesy of the Benavidez family.

As often as he could, Roy drove his Chevy the more than one thousand miles back to El Campo to visit Lala. The young couple spent hours talking. “When all you’re allowed to do is talk, boy, do you talk,” he explained of their closely monitored courtship. Lala listened to Roy’s perspective about race and discrimination. He recalled that she was understanding but also helpful in softening the deep-seated resentment he carried from his formative years. “She helped me kill all of those old dragons,” he wrote of the angry storms of his youth, even though he would never fully move past the pain of those difficult days. At times, they managed a little more intimacy, sneaking in some kissing and handholding in the darkness of a movie theater. This lasted for about six more months before Roy proposed marriage to Lala, on December 30, 1958.51

Roy and Lala were married in a traditional ceremony on June 7, 1959, at St. Robert Bellarmine Catholic Church in El Campo. Lala wore a beautiful ball gown with long sheer lace sleeves and a crown of white flowers on top of her veil. She walked down the aisle on her father’s arm, carrying an orange lace bouquet. Roy sported a fresh crew cut and was decked out in a black tuxedo with a white corsage. He looked as handsome as he ever had in his life. He could see that Lala was “smiling shyly” at him from behind her veil. They were a beautiful, beaming couple, surrounded by eighteen attendants, including the flower girl and ring bearer. More than 150 guests watched the nuptials. They celebrated afterward with a barbeque reception in the parish hall.52

Roy and Lala’s wedding, 1959. Courtesy of the Benavidez family.

Roy and Lala took a honeymoon to Monterrey, Mexico, about a 380-mile drive from El Campo. They stayed just outside the city near the base of the Sierra Madre Mountains, close to a waterfall known as Cascada Cola de Caballo—“Horsetail Falls.” Roy remembered stopping at San Juan, Texas, in Hidalgo County on the way home, where the young couple visited the Shrine of La Virgen de San Juan del Valle and made their secret “promesas” for their marriage.53

After their honeymoon, the newlyweds made their home at Fort Gordon, where Roy had been stationed for about a year. During his time there, he earned marksmanship badges in rifle, carbine, and pistol. In August of 1958, he had finished his military police training and was assigned as a chauffeur to the base commander. What seemed like a cushy job was a bit more involved than merely sitting behind the wheel. Being a driver also included doing personal favors for the general and his family. “As ‘driver,’” Roy wrote, “I have babysat, prepared meals, and run errands.” At one point, he was assigned to be the driver for William Westmoreland, who at the time was the commander of the 101st Airborne and who would later become the head of the United States armed forces in Vietnam. Roy recalled Westmoreland asking him, “Have you ever thought of going Airborne?” Roy and Lala remained at Fort Gordon for another year and ten months, the remainder of his second three-year enlistment in the United States Army.54

On March 24, 1961, Roy reenlisted again, this time for six more years. He had risen to the rank of sergeant, a promotion that came with a monthly salary of more than $200 (about $1,900 today). Roy was sent to Army Airborne School, an assignment he had long desired and one that would increase his pay. Roy and Lala packed up and headed to Fort Bragg in Fayetteville, North Carolina. “I planned on being the best trooper they ever had go through that jump school,” he remembered.55

In North Carolina, Roy and Lala lived in a tiny rental house located about thirty minutes from Fort Bragg. Roy remembered getting up every morning “before the sun came up” to drive to the base, only to return in the darkness of night. The training began with jumping off a tower. “I almost killed myself,” Roy recalled of that first jump. “I felt like a drunk puppet on a string.” “I never had been so tired in my whole life,” he explained of those first days of airborne training.56

Jump school was hard, “tougher than anything I had done since joining the army,” Roy reflected. He considered quitting to return to his old job at Fort Gordon. But as an advanced soldier, he was tasked with leading a platoon. As a leader, it was his responsibility to help get the younger troops through the difficult course. “I met my men and saw what they looked like,” he resolved. “I knew when I saw them that I couldn’t quit, and I determined that none of my soldiers would quit either.” Roy and his men made it through the rigors of airborne training. They were soon up in planes and jumping out over the pine forests of central North Carolina. On May 12, 1961, he received his certificate of completion.57

Roy in jump school at Fort Bragg. Courtesy of the Benavidez family.

Roy spent much of the next four years hopping out of airplanes. He was part of the 82nd Airborne, one of the most storied units in the United States military. The 82nd had been among the troops who parachuted behind enemy lines during the 1944 D-Day invasion of Normandy. In the early 1960s, they were battle ready and on alert. If the United States ever did go back to war, it was almost certain that the 82nd would be among the first units dropped into combat. Some considered it the most important unit in the entire United States military. As their commander bragged in 1962, “These are the world’s best soldiers.… They know it, and they’re proud of it.” “Tough, hardy and led by battle-seasoned officers,” noted a Los Angeles Times feature from that same year, “the 82nd is therefore preparing for warfare in any area—from the Arctic to desert to jungle.”58

There was probably never a time when the 82nd was on higher alert than during the Cold War in the early 1960s. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion in April of 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962 pushed the United States to the brink of war with Russia. The Berlin Crisis of 1958 to 1961 also frayed relations between the United States and the Soviets, evidenced most distinctly by the erection of the Berlin Wall in 1961. That same year, the American-backed Dominican Republic president Rafael Trujillo was assassinated in Santo Domingo, spinning that country into a civil war. Other potentially volatile episodes arose in places such as Venezuela, Brazil, Vietnam, Iraq, and Algeria. By 1962, the United States military covered a larger expanse of the globe than any military in the history of the world, with roughly 850,000 people stationed in more than one hundred countries.59

Lala pinning St. Christopher medal on Roy at Fort Bragg, 1965. Courtesy of the Benavidez family.

Between April of 1961 and December of 1965, Roy was stationed primarily at Fort Bragg. During that time, he was able to pass the General Educational Development (GED) exam. Thirteen years after dropping out of school, Roy finally earned the equivalent of a high school diploma, a proud moment in his life that helped rectify his lack of formal education. He spent a little time in Alabama and a bit more back at Fort Ord in the spring of 1965, but Fort Bragg was otherwise home for him and Lala. “The peacetime military is a hard enough life for a wife,” Roy acknowledged. “Many can’t take the constant moving and the instability.” “I look at the pictures that were taken of us then and realize how young and inexperienced we were,” he reminisced of those first years of marriage.60

Toward the end of 1965, Lala became pregnant with their first child. Even with this blessing, their lives were about to become much more difficult. That autumn, Roy received new orders that would take him back overseas. He was going to Vietnam, where the United States was rapidly increasing its military presence to contain the spread of communism. At age thirty, with more than thirteen years of experience in the military, Roy was headed into his first war.