CHAPTER 10

A HERO

Roy’s Medal of Honor ceremony was scheduled for February 24, 1981. There was much to do to prepare for the trip to Washington, DC. A few days before the ceremony, an Army officer named Captain Hayes came to El Campo to assist the Benavidez family with the arrangements. Hayes helped Roy submit the names of dozens of guests who would need to undergo background checks, and he spent hours briefing Roy on every detail of the coming ceremony. Hayes was with the family so often during those days that he started answering their telephone and greeting visitors at the front door. He even gave the kids rides to school. Fourteen-year-old Denise was tickled by the excitement. “It was mind-boggling,” she remembered. “Dad was going to be treated royally.”1

Receiving the Medal of Honor is like a coronation of sorts for American soldiers. It certifies their incredible heroics in combat and provides entry into a uniquely prestigious society with special benefits and honors. But the medal meant even more for a man like Roy Benavidez. To Roy, the Medal of Honor signified not just battlefield heroics but a triumph over the obstacles he’d faced across the broad sweep of his life. Roy couldn’t wait for the trip. He knew the ceremony would be his “proudest moment.”2

Many in El Campo were also excited. Over the years, some local residents had heard rumors about Roy’s military feats, but few could have fully appreciated the extent of his heroics before the Army verified his actions with the nation’s most prestigious military honor. Roy was going to the Pentagon to receive the Medal of Honor from the president. Small-town brushes with fame don’t get much more regal than that.

When Roy’s award was announced the previous December, a group of local elementary school students took up a collection to purchase a framed photograph of Roy for their classroom. Roy was deeply touched. “When I think about these kids,” he told a reporter, “when I realize how proud my fellow citizens are of me, its [sic] brings a lump to my throat.” The Pentagon let the kids keep their money by sending over a picture free of charge.

Throughout that December and January, the El Campo Leader-News kept readers abreast of Roy’s activities. The newspaper’s owners, the Barbees, had played a major role in helping Roy obtain the medal, and they remained close friends with him. “[Roy] was always making the news,” Chris Barbee reflected. He certainly appeared in their paper all the time. In their sleepy little town, he was the most interesting story of 1981. Three days before the ceremony, the El Campo Leader-News ran a front-page story previewing the Benavidezes’ trip. It showed a picture of Roy receiving a last-minute haircut from his barber and included a brief outline of his schedule. Talk of the upcoming ceremony buzzed across town, with locals discussing the event over coffees and lunches. Friends and strangers alike would stop Roy in public to express their appreciation. “Congratulations, Roy,” they would say. “We’re proud of you.”3

Not everyone was happy. A few days after Roy learned about the medal decision, he and Lala attended a Christmas dinner at the local American Legion. At one point, the club commander stood to greet everyone and introduce some of the legion officials and organizers of the event. In doing so, the commander also offered a “special welcome” to Roy and Lala, noting that Roy was soon to receive the Medal of Honor. A table away, an intoxicated man started booing loudly and yelling that Roy did not deserve the award. The man’s dinner party quickly shushed him, and the meal continued. The post commander later assured Roy that the man was drunk and out of line. But Roy was stung.4

Although most locals seemed to support Roy, he could always sense a slight chill, especially from some of his Anglo neighbors. Even though many years had passed, this was the same place where Roy was once called “greaser,” “spic,” and “taco bender,” and forced to eat his meals in the back of the restaurant where he worked. Some of the people from that era still lived in town. Times had changed, but there were still incidents and comments that invoked the same prejudices from the past. Unlike during his childhood, Roy generally managed to hold his tongue to avoid conflict.5

The social slights weren’t necessarily only about race. “To some,” Roy explained, “my efforts [to obtain the medal] had been no more than an arm twisting political campaign to pressure the army and the federal government into taking action where none was needed.” Roy’s detractors did not fully understand the process or standards for receiving a Medal of Honor. They suggested he was no war hero but rather an irritating opportunist who used personal connections to secure a recognition he did not deserve.6

Nevertheless, Roy carried on, buoyed by the coming ceremony at the Pentagon and other honors that started coming his way. In January, the Texas 82nd Airborne Association wrote to share that their members had unanimously voted to rename their museum for him. Roy was invited to be a speaker and guest of honor at the Wharton County DeMolay Club and the annual banquet of the El Campo Chamber of Commerce and Agriculture. He also received a letter from the Special Forces center at Fort Bragg, the place where he once trained, congratulating him on the forthcoming award and informing him that they planned to add his portrait to their JFK Hall of Heroes.7

During the week of the ceremony, ABC World News Tonight sent reporter David Ensor to El Campo to film a segment about Roy and the upcoming ceremony. After a brief introduction from lead anchor Sam Donaldson, Ensor narrated the three-minute story, which included several clips of Roy describing the battle of May 2, 1968, and of Roy walking through an El Campo neighborhood. “President Reagan is rolling out the red carpet,” Ensor told viewers. “By choosing to make the award himself,” Ensor observed, “President Reagan seeks to send a message to Vietnam veterans in towns like this one [El Campo] around the country that he will not ignore them, and he puts the Presidency behind an effort to renew American pride in military service.”8

Roy’s Medal of Honor ceremony presented the new president Ronald Reagan with an opportune moment. Although it was President Carter who had signed the law that enabled Roy to receive the medal, the newly inaugurated president Reagan had the pleasure of bestowing it upon Roy. Carter was a lame duck by the time Roy’s medal was approved. He had signed off on the legislation based on the recommendations of his staff and the Department of Defense, but he did not push to make the award himself because, according to Reagan’s secretary of defense, “the Carter Administration had not wanted to do anything that reminded people of Vietnam.”9

President Reagan, on the other hand, was thrilled for the opportunity to present a Medal of Honor to a Vietnam War veteran. In office barely more than a month, Reagan looked forward to demonstrating his administration’s commitment to the rejuvenation of the military. He learned in mid-February that Roy was due to receive the medal and jumped at the chance to hold a big ceremony. When Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger told Reagan that “a soldier with a trained voice” usually reads the citation, the president replied, “I have a trained voice.” Weinberger checked with the Pentagon to make sure that Reagan would not be breaking protocol by reading the citation himself. It is believed that Reagan became the first president to read the formal citation during a Medal of Honor ceremony.10

The United States, eight years removed from its involvement in the war, remained mired in Vietnam syndrome. Much of the country still felt a sense of collective national guilt, and many felt that the Vietnam War signified a troubling decline in American military power. Vietnam syndrome remained pervasive in the years after the war’s end, as countless books, magazine articles, and films depicted the American war effort in Vietnam as misguided and immoral. Movies like The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979) cast American military leaders and soldiers as bloodthirsty maniacs who had lied to the country’s public. The Iran Hostage Crisis, between 1979 and 1981, further crippled public confidence in the military and government, even among the most ardent supporters of the military who saw the response from the Carter administration as a sign of weakness.11

Ronald Reagan had long been a staunch supporter of the Vietnam War. In October of 1965, while running for governor of California, he declared that the United States military could use its overwhelming power to “pave the whole country [of Vietnam], put parking strips on it and still be home by Christmas.” While joking in tone, his statement was horribly misguided, dripping in the very same brand of American hubris that would cause the war to go so awry.12

As governor of California in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Reagan defended Nixon’s wartime policies. After the war, he routinely criticized Congress and President Lyndon B. Johnson for wartime strategies that, he argued, prevented American victory by forcing the military to operate “with their hands tied behind their back.” Throughout his political career, Reagan insisted that the United States should have won in Vietnam, even as he offered no specifics on how, or precisely what such a victory would have meant for Americans. Unlike much of the rest of the country, he seemed uninterested in reflecting on whether the United States should have been in Vietnam in the first place. In 1975, he argued that the war was lost because America’s politicians “gave up,” calling the American withdrawal from Vietnam more shameful “than any single event in our nation’s history.”13

When Reagan ran for president in 1980, he publicly defended what was still an unpopular war. That summer, he took the stage in front of five thousand attendees of the VFW Convention and told his audience exactly what many of them wanted to hear. The Vietnam War was a “noble cause,” Reagan insisted. “We dishonor the memory of fifty thousand young Americans who died in that cause when we give way to feelings of guilt as if we were doing something shameful.” “Let us tell those who fought in that war,” Reagan continued, “that we will never again ask young men to fight and possibly die in a war our government is afraid to let them win.” He told the VFW that Jimmy Carter ran an “anti-veteran administration,” and he promised to do more to help America’s veterans.14

Coverage of Reagan’s remarks appeared in virtually every major newspaper in America. Members of groups like the VFW and American Legion loved his message. The audience at the VFW Convention interrupted Reagan’s thirty-minute speech with twenty-six ovations. Reagan’s remarks drew a heap of criticism among those familiar with the war, but it was also welcomed by millions of Americans who refused to question the sanctity of the United States military.15

As a candidate during the 1980 election, Reagan worked to cast President Carter as weak and indecisive, likening him to the Democrat politicians who, he argued, had failed America in Vietnam. Reagan sought to separate the war’s soldiers from its architects, celebrating the fighting men while blaming political leaders for their lack of success. “It is time we purged ourselves of the Vietnam syndrome,” he insisted that March, “which has colored our thinking for too long.” Reagan worked to build support among veterans and military boosters, appealing to the pride and patriotism of people who wanted to see America restore its predominant role in the world and renew its fight against the threat of global communism. Whereas Jimmy Carter in 1977 had stated, “We are now free of that inordinate fear of communism,” the Republican party platform of 1980 argued, “The scope and magnitude of the growth of Soviet military power threatens American interest at every level, from the nuclear threat to our survival, to our ability to protect the lives and property of American citizens abroad.”16

Reagan saw the United States of America as an arbiter of good in a dangerous world threatened by the evils of communism. The Soviets, he argued, sought a “one-world Communist state.” He mocked Jimmy Carter’s 1977 remarks throughout the 1980 campaign, emphasizing the need to face down communism across the globe. “The West will not contain communism,” he promised, “it will transcend communism.” Reagan leaned into the conflict of the Cold War, rejecting his predecessors who had argued for détente, disarmament, and a cooling of tensions with Russia and other communist nations. In a press conference held just days into his term, Reagan quipped, “So far détente has been a one-way street the Soviet Union has used to pursue its own aims.” That same week, his secretary of state openly accused the Soviet Union of fostering “international terrorism.” And just ten days into Reagan’s term, the New York Times called his administration’s stance “an unprecedented verbal assault on the Soviet Union by a new Administration.”17

As promised in his campaign, Reagan sought to ramp up spending on pro-American propaganda and military expenditures. In doing so, he recognized the need to restore the prestige of the military. The pomp and circumstance of a Medal of Honor ceremony presented an opportune moment for a grand celebration of the armed forces. In office for barely more than a month before the Roy Benavidez Medal of Honor ceremony, the president couldn’t wait to call the Army back to center stage.18

The Benavidez family left for Washington on the morning of February 22. Roy took nearly his entire family with him, along with his friends from the newspaper, Chris and Fred Barbee and Steve Sucher. The entourage of more than forty guests left El Campo in a Greyhound bus that drove them the one hundred miles to Houston’s Intercontinental Airport (now George Bush Intercontinental Airport). From there, they flew into Washington National (now Reagan National) and stayed at the Crystal City Marriott in Arlington, Virginia. The Benavidez family and their friends occupied an entire floor of rooms, and the floors above and below their block were left empty. Roy and Lala’s suite was “decked out in flowers and baskets of fruit and cheese,” he remembered.19

On Monday the 23rd, Roy was fitted for two new dress uniforms while his family toured the nation’s capital. Later that afternoon, he met with government officials who explained the benefits attached to the Medal of Honor. As a recipient of the military’s highest award, Roy was entitled to a free seat on military aircraft flying within the United States, a supplemental uniform allowance, priority burial at Arlington National Cemetery, a lifetime invitation to presidential inaugurations, and several other privileges on military bases. He would also receive a supplementary pension of $200 per month. Roy submitted the pension paperwork the next day.20

That evening, Roy relaxed in his hotel room with his loved ones. As the night wore on, family gradually gave way to some of Roy’s Army buddies who had traveled to Washington for the ceremony and made their way to Roy and Lala’s suite to greet their friend. Some of the visitors were men involved with the May 2 mission. Colonel Ralph Drake came. Jerry Cottingham, the man who recognized Roy in the body bag and alerted the medic, was there. Chandler Carter, a helicopter pilot who had sat on standby listening over the radio as Roy directed supporting attacks, arrived from Alaska. Each of these men had completed notarized witness statements verifying Roy’s heroics and supporting his pursuit of the medal. It meant a lot to Roy for them to be there. He described that evening as filled with “a flow of old buddies coming to the suite to visit and shoot the bull just like the old days.”21

Later that night, after most everyone else had left, Drake returned to Roy’s door with another guest. Drake stepped aside to reveal that the man behind him was none other than Brian O’Connor. Roy and O’Connor locked in an embrace, fighting tears as they held onto one another. Each man was there because of the other. Roy had saved O’Connor’s life, and O’Connor’s testimony the previous July had proved to be the deciding factor in the Army’s decision to award Roy the Medal of Honor. Although the men had spoken on the phone, they still hadn’t seen each other since May of 1968, in that Saigon hospital. “Last time I saw him,” O’Connor told reporters, “he was floating in his own blood.”22

That night, Roy and O’Connor spoke of those who did not survive that dreadful day in Cambodia. They spoke of Leroy Wright, Lloyd Mousseau, and Larry McKibben, who would have turned thirty-three that year. Roy and O’Connor were deeply emotional, each remembering those terrifying hours spent surrounded by enemies. Either of them could have easily been among the dead. Neither man had ever completely left that jungle. Roy and O’Connor had not actually spent a great deal of time together in Cambodia, but those moments in the field defined their lives and bonded them as closely as brothers. The war would be with them always. “O’Connor and I had something in common,” Roy explained of their friendship. “We each knew that the other had been through hell.”23

The next morning, Roy enjoyed breakfast with his family in the hotel dining room. He was briefed once again about the day’s schedule. Only four years retired, Roy still appreciated the detailed plan of a day in the Army. He had always liked the organization of military life. The hierarchy made sense to him; it had provided order out of an otherwise unsteady youth. Unlike in his childhood, men in the Army were mostly judged by rank and accomplishments. It just so happened that on that day, February 24, 1981, the most accomplished man was him.24

The main action began just after 11 a.m. Roy traveled to the Pentagon to eat lunch with Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger and Secretary of the Army John March. The men shared a laugh when Secretary Weinberger followed Roy’s example of piling spoonfuls of pico de gallo on top of his steak, only to be rebuffed by the level of heat the spicy topping added to his beef. “I’ll never forget the look on his face,” Roy cheerfully recalled of the defense secretary. After lunch, he returned to the hotel.25

Throughout the day, Roy could feel the weight of the moment set against the backdrop of his forty-five years of life. Here, after all, was a lifelong underdog, one of America’s poorest sons, the offspring of a disadvantaged minority race, raised earning a living picking cotton and sugar beets for a nation that barely recognized his existence. Roy’s experiences had long suggested to him that he was among the most undeserving groups in America. His family worked hard and carried themselves with dignity, but he came from people who had no reason to expect much recognition.

In his youth, Roy had resented his status and craved respect. The Army provided a pathway toward social mobility, but it wasn’t an easy or equal path. Roy knew of many higher-ranking officers who’d entered the service under better circumstances, former high school superstars who had earned admission to West Point and gone on to become colonels and generals. Without a college degree, Roy lacked the same prospects. He had served in the Army because he saw no other opportunities; he understood that the blue bloods of the American military commanded more respect than a Hispanic eighth-grade dropout who had enlisted in his teens. But on that day, Roy would be feted by the entire government at the Pentagon. A devotee of tradition, he welcomed the attention and basked in the proceedings that brought him so close to eminency. On that day, he was more than just a war hero; he was the realized dreams of his family.

Just before one o’clock, Roy, Lala, and their children were driven to the White House to meet with the president and first lady. Roy looked sharp in his crisp new Army greens. Lala wore a blue dress suit with a white corsage pinned to her lapel. Denise and Yvette, aged fourteen and eleven, wore red jackets adorned with white corsages like their mother’s. Noel, just eight years old, was smartly dressed in a dark blue suit.26

Roy’s family met the Reagans in the Roosevelt Room and then proceeded into the Oval Office. Lala spoke with Nancy Reagan as Roy chatted with the president. It was a surreal experience. The extroverted war hero looked uncharacteristically nervous and awkward. Roy was rarely shy, but he was rendered starstruck by the commander in chief, and he quickly retreated to the decorum expected of a noncommissioned officer meeting a higher-ranking superior. President Reagan was new to this as well. He’d barely been in office a month and had certainly never been part of a military ceremony of this magnitude. The start of Roy’s conversation with the president consisted of a lot of small talk and “yes-sirring and no-sirring,” Roy recalled.27

Noel helped break the ice. As the solemn adults settled into the occasion, Roy’s son began eyeing Reagan’s now famous jelly bean jar. The president noticed Noel’s interest and offered him a piece of the candy. When Noel nodded enthusiastically, Reagan handed him the entire jar. Roy joked that he too wanted a jelly bean, and everyone chuckled as they passed around the container. “After that,” Roy recalled, the rest of their time in the Oval Office was “a breeze.” A few minutes later, the group was joined by Secretary of Defense Weinberger and Reagan’s advisor Ed Meese.28

After about fifteen minutes in the Oval Office, the president and first lady escorted the Benavidez family to the South Lawn, where vehicles were waiting to drive them to the Pentagon. Roy and Lala rode in the presidential state car with the Reagans and the secretary of defense. The Benavidez children followed in another vehicle. The quick ride in the presidential motorcade was thrilling. People along the sidewalks stopped to “watch and wave,” Roy recalled. As he and Lala rode through Washington, DC, with the president, the hero’s thoughts drifted back to his childhood. “It was literally more than I could conceive,” he remembered, “that a little ol’ barefoot Mexican-American farmboy from Cuero and El Campo, Texas could ever find himself in such company.” He “had to hold back tears,” he remembered, “thinking about how far this black taxi was from that little ‘jitney’ cab in El Campo.”29

The presidential party arrived at the Pentagon at about one thirty and was escorted to the Hall of Heroes, the long corridor filled with portraits of Medal of Honor recipients. They were greeted there by another group of high-ranking officials: Vice President George H. W. Bush and his wife, Barbara, Army Chief of Staff Edward C. Meyer, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the secretary of the Army, the sergeant major of the Army, and the secretary and deputy secretary of defense along with their wives. After the brief welcome, the entire party proceeded down a set of stairs into the central courtyard of the Pentagon. Roy and Reagan would enter last.30

It was a warm and windy winter day, with high temperatures in the mid-fifties. Neither Roy nor the president wore a coat. Everyone at the Pentagon was invited. “Every window on the Pentagon courtyard was jammed with onlookers,” observed a Washington Post reporter. Reagan was big on appearances, and his administration sought to reestablish acts of military decorum. He ordered all military personnel to don their service uniforms for the Benavidez ceremony. The Pentagon courtyard was a sea of caps, berets, and military service flags. “I haven’t seen so many uniforms around here in years,” one officer told a reporter.31

With horns blasting and the audience cheering, Roy and Reagan descended the stairs into the courtyard. Roy stood a head shorter than the six-foot-one president. Dozens of photographers snapped pictures as the pair walked together toward the center of the courtyard, pausing for a moment as the military band played “Hail to the Chief.” Then, an Army officer escorted the chief and the hero through the courtyard to inspect the Honor Guard. A throng of civilian onlookers, surrounded by cameras, clapped and waved as hundreds of uniformed men and women watched stoically.32

Roy, standing short and stout, looked out of place among the young, fit soldiers who were immaculately clad in their best dress uniforms. But on that day, he was the brightest hero of them all. And he knew it. One could see it in his walk. He strutted alongside the president with the swagger of a giant, strolling by the throng of onlookers, passing troops from every branch of the military, and stepping up onto a red carpeted platform, where chairs awaited him and the president. For the next few minutes, it was just Roy and Reagan in the middle of the stage.33

Roy and President Reagan inspect the troops, 1981. Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

Roy soaked it in. He and Reagan watched performances by the US Army Drill Team and the Fife and Drum Corps, outfitted in their colonial-era red coats and white pants. Roy looked on, watching the impressive unit twirl and shoulder their weapons, the courtyard filling with the rhythmic click-clack of their synchronized gun movements. Roy seemed attentive but anxious. He fidgeted in his chair and fiddled with his program. Later, he said that his leg began throbbing during the Honor Guard inspection. As the military drills wound down, Roy and Reagan glanced at each other and exchanged a smile. Then, the secretary of defense walked onstage to introduce the president.34

“Mr. President,” Secretary Weinberger said, “it is especially fitting that you honor us today with your presence here because of your clear and long-standing support for those who wear the uniforms of the United States armed forces.… And I share and support your pledge to restore the pride that we as a nation once felt, and should feel again, for those who serve all of us so selflessly and, in the case of Sergeant Benavidez, so magnificently.” The audience politely applauded.35

Reagan then took the podium as Weinberger sat down. “Several years ago,” he began, “we brought home a group of American fighting men who had obeyed their country’s call and who had fought as bravely and as well as any Americans in our history. They came home without a victory not because they’d been defeated, but because they’d been denied permission to win.” At this, the crowd in the Pentagon courtyard erupted in applause. They’d been craving such a message for years—through all the anti-war protests, through the endless hearings and mortifying revelations, and through the dishonorable departure from Saigon and the fall of South Vietnam. Many of those in the courtyard were members of a once-proud military who felt they had been unfairly shunned by their society. They soaked in the new president’s praise. Finally, they were getting the respect they felt they deserved. Reagan paused to let them finish clapping before he continued.36

“There’s been little or no recognition of the gratitude we owe to the more than 300,000 men who suffered wounds in that war.” The president mentioned “recent movies about that war” that showed negative depictions of the American forces in Vietnam, and he stated that he wanted to help set the record straight. He highlighted “examples of humanitarianism” that “none of the recent movies about that war have found time to show.” He talked about the number of schools and hospitals built by American troops. He shared stories of servicemen adopting Vietnamese orphans and building houses for lepers. For Reagan, Vietnam veterans were merely the misunderstood victims of an incompetent foreign policy and a misguided public. “It’s time to show our pride in them and to thank them,” he insisted.37

Reagan circled back to Roy. “I have one more Vietnam story,” he told the crowd. At this, Roy and Secretary Weinberger rose to face the president. The pair stood just off to Reagan’s right as the commander in chief read the full Medal of Honor citation himself, an unprecedented gesture for a president before Roy’s ceremony. It took the president a full five minutes to read the official citation describing Roy’s remarkable acts of valor. Roy stood in what he described as a “trance,” swaying ever so slightly, taking deep breaths, and occasionally scanning the crowd. His face held a serious look. Roy later explained that his mind was occupied by thoughts from that day in Cambodia.38

This moment was a preview of a scene that would repeat itself throughout the rest of Roy’s life. Honored as he was to receive the Medal of Honor, public recognition of his actions also often required him to relive the most traumatic experience of his life. Roy rarely described his own heroics in public, choosing instead to let others tell the story. One can only speculate why. Perhaps he was too humble. Or maybe it was simply too painful to discuss those experiences with people who have never seen combat. But others did speak about Roy’s actions in great detail. All they had to do was read the Medal of Honor citation. Those who sought to honor Roy, both during and after the Medal of Honor ceremony, unwittingly dragged his thoughts back to the violence of that Cambodian battlefield. It was another weight that Roy would have to carry, a burden of sorts that accompanied his new status as a national hero.

Roy and Reagan during 1981 Medal of Honor ceremony. Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

As Reagan finished reading the citation, a lieutenant colonel brought the medal onstage and stood behind the president. Reagan took the Medal of Honor and placed the award around Roy’s neck, allowing the officer to affix the ribbon to the back of Roy’s collar. The president then shook Roy’s right hand and gently touched Roy’s right elbow. As their hands unlocked, Reagan leaned toward Roy and pulled the hero closer. Roy was surprised. “It wasn’t exactly military protocol,” he later wrote. “I started to step back and salute the President, but before I could move, he reached forward and grasped me in a hug.” Unbeknownst to the audience, Roy stepped on the president’s shoe during their impromptu hug. But neither man seemed very bothered. When they separated, Roy stepped back and saluted. The president responded as he normally did, by placing his hand over his heart.39

The president looked at Roy, beaming, as the men stood for their photograph. They stood at attention, Roy in a salute and Reagan with his hand over his heart, as the military band played “The Star Spangled Banner.” Pictures of the two onstage were reprinted the next day in hundreds of newspapers across the United States. Reagan was deeply affected by the ceremony. “It was an emotional experience for everyone,” he wrote that night in his diary.40

Unsurprisingly, those in the crowd loved Reagan’s sentiment and remembered the ceremony for years to come. Colin Powell, a Vietnam veteran who would go on to become chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and later secretary of state, was in attendance. “That afternoon marked the changing of the guard for the armed forces,” he wrote in his 1995 memoir. “We no longer had to hide in civvies. A hero received a hero’s due. The military services had been restored to a place of honor.”41

Dozens of media outlets offered similar interpretations. With headlines like “President Reagan Lauds Vietnam Vets,” “Reagan Extends Overdue ‘Gratitude’ to Vietnam Veterans,” and “Reagan: Viet Vets Overlooked ‘Too Long,’” American newspapers also seemed to understand that this ceremony was meant to honor more than just a single veteran. So did Roy. “I know I’m a symbol in the eyes of the public,” he told a reporter that day. It was “a high honor,” he said, to serve as “a stand-in for all the millions who served over there.”42

After the thirty-minute ceremony in the courtyard, Roy and Reagan returned to the Hall of Heroes to take part in a receiving line. Roy and Lala stood with the president and first lady as attendees approached to pay their respects. Passersby shook the hand of the president, then Roy, then the first lady, and then Lala—the working-class Hispanic couple from South Texas receiving guests alongside the president and his movie star wife. By then, Roy’s nerves had steadied. He was acting more like himself, cheerful and playful, repeatedly tapping Reagan on the arm to share a comment and greeting those who passed by with a witty quip and a smile. Some people wanted to hug him, and he welcomed their embrace. Brian O’Connor came through the line and paused for a photograph with Roy and the president. The three of them shared a laugh over something Reagan said. The event lasted about ninety minutes before the president and first lady left to return to the White House.43

Afterward, Roy and his family were “exhausted,” he wrote. They enjoyed some downtime at their hotel, where they reflected on the day’s events. A few of Roy’s old military buddies came by that afternoon and evening to say farewell. The next day, Roy’s entourage went back to the White House for a group photograph on the White House steps. Then they all boarded a flight for Texas. Roy had no idea about the surprise that awaited his return.44

After Roy and his crew landed in Houston, they boarded a chartered bus that drove them back to El Campo with a police escort. Instead of taking Roy home, the bus went to El Campo High School. When Roy stepped off at about 7:45 p.m., he was met by school officials who welcomed him back from Washington, DC, with what they called a “public ‘surprise party’” at the high school gymnasium.45

Reagan and Roy with Brian O’Connor (center) at the Pentagon, 1981. Roy P. Benavidez Papers, camh-dob-017319_pub, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

That morning, the entire front page of the El Campo Leader-News was covered with stories about Roy. The Barbees had filed their firsthand accounts of the Washington ceremony from the road. Their articles were just two of five different stories covering Roy’s Medal of Honor ceremony. That morning’s newspaper also featured a photograph of Roy with President Reagan and a copy of the official Medal of Honor citation. The next page included another picture of Roy departing El Campo a few days prior and another story about his heroics and honors. On the third page appeared the notice of that night’s party and instructions for all who wanted to attend.46

Roy walked through a line of Boy Scout honor guards into the “Home of the Rice Birds,” a classic red-painted multipurpose high school gymnasium with fold-down basketball hoops, encircled by concrete seating and retractable bleachers. Waiting for Roy inside the gym was a raucous crowd of around 1,500 locals who had turned out to welcome home their hero. The El Campo High School band was in attendance, along with the Northside Elementary choir. Signs handmade by students hung from the walls.47

The event commenced with the high school band playing the national anthem. A priest from Roy’s church led an invocation before the emcee, a local reporter and radio man, took over the microphone. He began by playing a recording of President Reagan’s comments from the previous day. Next, a series of local dignitaries took the microphone to address the audience. Congressman Joe Wyatt spoke, as did the Wharton County judge and attorney and El Campo’s mayor, who declared the day “Roy Benavidez Day.” Two local citizens presented a special poem they had written to honor Roy, and the elementary school choir sang a song honoring Green Berets. Texas governor Bill Clements was unable to attend, but he called in to the rally on a rotary phone. An extension cord allowed Roy to hold the receiver up to a microphone so the crowd could hear the governor’s voice.48

Roy took the podium. He was thrilled and honored, practically glowing. In the years to come, Roy would appear in thousands of pictures. There is not one picture of him ever looking happier than he did in the photographs from that night at El Campo High School. “I certainly appreciate what you people have done for me, receiving me and my family this way,” he told the audience. “It’s really great to come back to people who really supported you.… And I appreciate even more those people who didn’t support me in this act because they encouraged me to fight.” “I’m proud to be a Texan,” he told them, “and I’m even prouder to have been given the privilege to serve my country.” After the event, Roy and his family returned home. Despite the ongoing celebrations, they could not have known just how much their lives were about to change.49

Roy Benavidez was suddenly famous. Coverage of his Medal of Honor ceremony appeared in almost every newspaper in the United States—from the Los Angeles Times and Boston Globe to smaller dailies like the Anniston (AL) Star and the Palm Beach Post. The story was everywhere. It was also broadcast on the nightly news of every major television station in the country.

The coming weeks and months were a whirlwind of recognition and adoration that helped give new purpose to Roy’s life. It started in Texas. In March, the city of Galveston welcomed Roy for its own “Roy Benavidez Day.” A week later, he visited the Texas Legislature, where Governor Bill Clements declared another “Roy Benavidez Day.” He met with members of the Texas House and Senate, who joined him for a private lunch at one of Austin’s most exclusive restaurants, followed by a special reception hosted by the governor.50

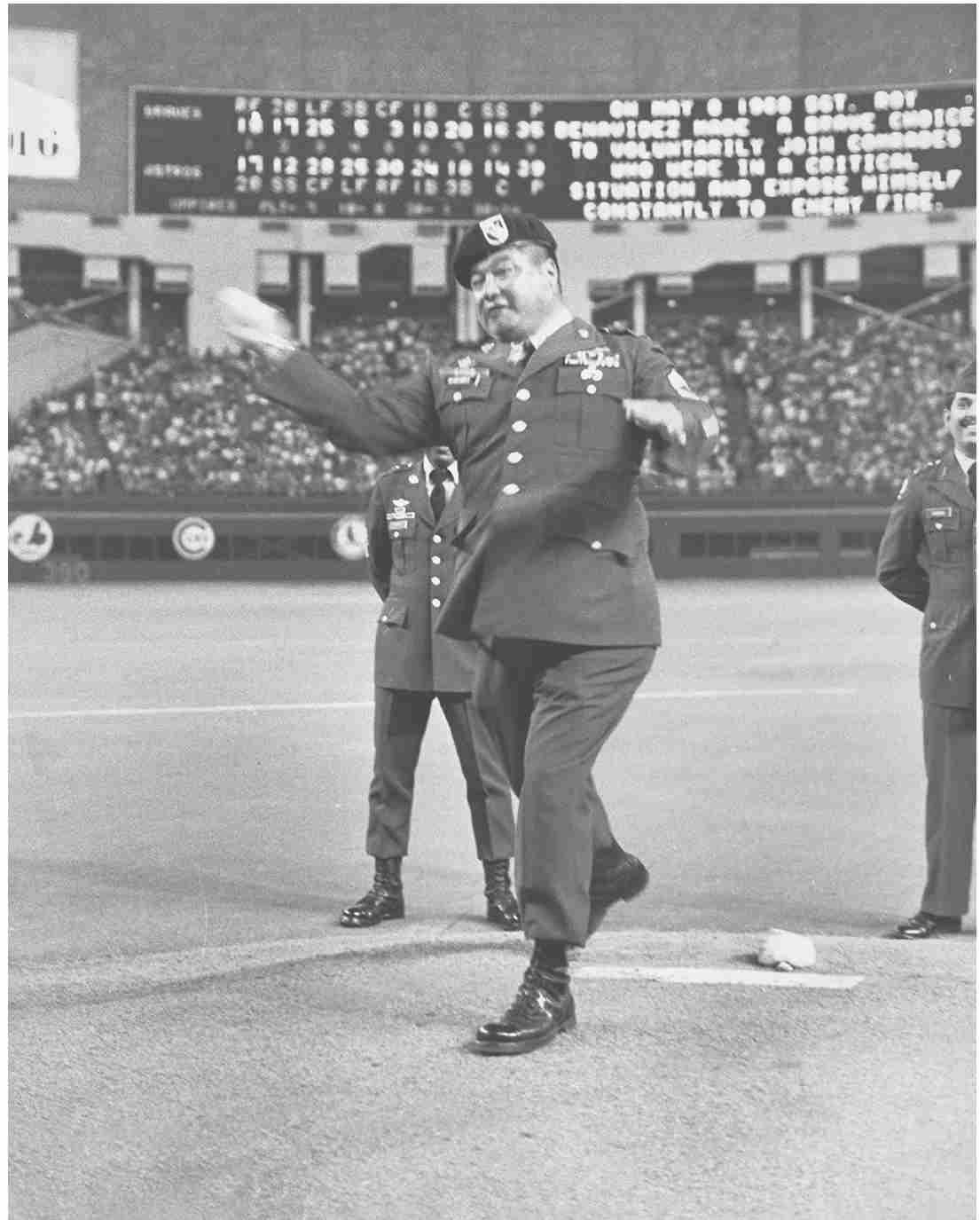

That spring was a good and busy one for Roy. He threw out the first pitch at the Houston Astros home opener, and his family visited the dugout to meet the team, including Hall-of-Fame pitcher Nolan Ryan. The Texas Press Association named Roy “Texan of the Year” and honored him and his family at a ceremony in Fort Worth. Wharton County Junior College, where Roy had briefly attended classes, awarded him an honorary degree.51

That spring, Roy began receiving dozens of invitations to speak. He spoke at rotary clubs, chambers of commerce, churches, hospitals, social clubs, and charity events. He served as grand marshal in several parades. In May, he traveled to Virginia where he spoke at an ROTC banquet at Virginia Tech before returning to Texas to speak at the commissioning ceremony for ROTC cadets at the University of Texas at Austin. “We’ve been having a tough time keeping up with El Campo Medal of Honor winner Roy Benavidez,” noted the El Campo Leader-News that spring.52

Roy was an inexperienced but extremely effective speaker. At every appearance, his message was simple: America was the greatest nation on Earth and patriotism was its most important value. When he spoke, he usually described the broad outline of a childhood mired in poverty and discrimination and talked about how he had dropped out of school. He then explained why he joined the military and credited the armed forces with pulling him off a dangerous path. Roy always had a few military jokes or lighthearted stories to make people laugh. He told his audiences how proud he was “to be an American,” which might have been the phrase he used most often. He’d often return to a handful of other sayings, such as “Quitters never win and winners never quit,” and “I am not a hero, the real heroes are those who never came back.” He loved to share that people often asked him if he’d do it all over again. “There will never be enough paper to print the money,” he’d answer himself, “nor enough gold in Fort Knox for me to have, to keep me from doing it all over again.” His commitment to the Army was cemented, as it was the service in that Army that first pulled him out of El Campo and now formed the backbone of his new identity as a war hero.53

Roy throwing the first pitch, Houston Astrodome, 1981. Roy P. Benavidez Papers, camh-dob-017307_pub, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Roy spoke with a thick South Texas accent. He had a deep voice with a twang, and his diction sounded like it came from the back of his throat. He used simple words. Few people would have called him elegant. But his timing was impeccable, and he was very funny. He commanded a room because of how he was introduced. Moderators would often share the story of his heroics, stunning audiences who became instantly fascinated by a man who had taken such punishment and demonstrated such courage. Kids who’d had no idea about the Vietnam War would be struck by the fact that Roy had been shot seven times. An alumnus of one of the high schools where he spoke remembered, “I was in that auditorium many times in my life, and I had never heard it so quiet.” Roy was a master of positivity and patriotism. He made other people feel proud to be American. And he complimented them and assured them all that they had a bright future.54

Roy loved to speak with young people more than any other group. “When it came to talking to kids, man, he was driven,” remembered Chris Barbee. “His mission was to tell every kid he could [get] hold of to mind their parents, stay in school, and go to church.” Roy would tell young people, “After what I’ve been through, I dedicated my life to come talk to you students. You’re the future of our country. You’re the future leaders.” “An education and a diploma,” he told them, “is the key to success.” He liked the kids, and the kids liked him. They would ask him silly questions that tested his wit—if he was scared or if it hurt when he got shot. He particularly enjoyed speaking with kids who came from backgrounds like his. He had read about poor high school graduation rates among Hispanic teenagers, and he wanted to show them a role model and encourage them to finish school. His speeches to youths were steeped in patriotism and flavored by the political messaging of the day: stay in school and stay off drugs. To the kids of the 1980s, he must have sounded like one of their D.A.R.E. officers.55

Roy would go on to give hundreds of talks in the years to come. He was reimbursed for his travel, but he almost always spoke for free. Even though traveling and speaking to large groups is time consuming and labor intensive, Roy did all of this, constantly and for the rest of his life, out of a sense of duty. As his close friend Chris Barbee recalled, Roy “felt the MOH carried with it a huge responsibility to continue to represent his country before young people, military personnel, and even prisoners.” Roy viewed those speaking engagements as part of his duty to the United States. This sense of duty compelled him to travel across the country and eventually the world, telling his story over and over, bearing all the trauma of his experiences and the difficulties of constant travel for a disabled man to share his message with other Americans.56

Roy’s sense of his duty also came from President Reagan, who had essentially asked him to help spread patriotism. At the Medal of Honor ceremony, Reagan had told Roy that he could help his country by telling youths about the greatness of America. A couple months later, Secretary of Defense Weinberger reached out to Roy to ask if the war hero would help with military recruitment. Roy accepted, and Weinberger informed the president that Roy would “be used in the Southwest Region Recruiting Command to speak to young people and educators on the importance of military service.” This role was never formalized, but Roy took the charge seriously. Ever the soldier, he viewed his speaking engagements as an order from his commander in chief. He rarely said no to an invitation. According to one regular travel companion, Roy also came to believe that speaking to young people had become his destiny, even “his purpose in life.”57

Roy ardently believed in the messaging. How could he not? This deeply personal faith in the military had been germinating since he was sixteen years old. He had staked his whole life to this faith in America and its military. When he spoke in the early 1980s, he was aware of the Vietnam syndrome Reagan referenced. “With old-fashioned patriotism in short supply…,” he later explained, “it didn’t seem too much out of line for one short, fat Mexican-American to stand up and publicly state that he was proud of the uniform he wore, the country he served, and considered it a privilege to wear its highest award.” He knew he was a symbol, one he hoped was capable of inspiring “the young people with whom I came in contact.”58

Roy’s approach invoked a strategy advocated by earlier generations of Latino veterans who belonged to groups like LULAC or the American GI Forum, which Roy later joined. His constant invocation of being “proud to be an American” was a reminder to others that he was one. It was an argument made before, both by his ancestors after the Texas Revolution and by Latino World War II veterans. But this time it had a chance to work.

Although Roy wasn’t typically paid for appearances, he received some nice perks. In April, a group of El Campo businessmen gifted Roy a brand-new Chevy El Camino for serving as grand marshal in a local youth parade. A month later, the State of Texas gave him customized Congressional Medal of Honor vanity license plates that entitled him to “free parking anywhere in the state” and free registration renewals for life. In the years to come, that car would take the hero all over the state, and the license plate ensured that everyone knew who he was. For years, folks on the Texas highways would smile, wave, and honk, yelling thank-yous and doling out handshakes as they encountered the military hero on the road.59

Roy’s appearances often served a political purpose. The 1981 Medal of Honor ceremony itself was the first of many examples of Roy being honored in a ceremony with deep political implications. Reagan put on such a show largely because he wanted the vote of veterans and those who supported the military. He and his advisors also sought the Latino vote. As Hispanic voters increased in number and political significance, both major political parties of the 1980s jockeyed for their support.

Dubbed “The Decade of the Hispanic” by contemporary commentators, the 1980s were revolutionary for Hispanic politics. America’s Hispanic population was growing faster than any other ethnic or racial group, making them major political players, especially in large states such as Texas, California, and Florida. Between 1974 and 1981, the number of Hispanic elected officials grew from 1,539 to 3,128. In 1981, Henry Cisneros became the first Hispanic mayor of a major US city after winning election in San Antonio. As one journalist observed in 1980, “The Hispanic giant in the United States is awakening.”60

In the early 1980s, most Latino voters, who are much more diverse than other ethnic groups, were solidly Democratic. In 1980, Reagan won more than 30 percent of the Hispanic vote, a record for a Republican, but his approval rating slipped early in his presidency. In 1982, over 75 percent of Hispanic voters said they were likely to vote Democratic in the next election, largely for economic reasons. Reagan responded by courting Hispanic voters over issues such as conservative family values, religion, education, and anti-communism, which played particularly well with Cubans in Florida. He touted Latinos as proud Americans, emphasizing the accomplishments of Hispanic immigrants and pointing toward representative heroes. He also appointed dozens of Hispanics to government positions.61

Ronald Reagan loved heroes, and in the early 1980s, Roy Benavidez was the president’s greatest Latino hero. Reagan mentioned Roy often when speaking to Hispanic groups. He toasted Roy when hosting the president of Mexico at Camp David in June of 1981. He mentioned Roy when speaking at a White House ceremony for Hispanic Heritage Week in 1982, calling the previous year’s Medal of Honor ceremony “an unforgettable experience.” He brought up Roy at a Cinco de Mayo ceremony in San Antonio in 1983, crediting the Medal of Honor recipient with helping to make America “free and independent.” Later that summer, he discussed Roy during an event with the American GI Forum in El Paso, and he spoke of giving Roy the Medal of Honor during a White House meeting of the National Hispanic Leadership Conference in 1984. “I had the pleasure of giving him his medal,” Reagan told the group. “I don’t know what had stalled it. It had been lying there, not delivered to him.”62

There was a similar dynamic in Texas. Roy was close with a handful of Texas state legislators, who appeared with him at rallies, parades, and various events related to veterans or the military. One of the first to latch on was Frank Tejeda, a Hispanic Vietnam veteran who served in the state legislature. So, too, did Republican governor Bill Clements, who reunited Roy and Reagan in 1982, the year after they first met, when he asked each to speak at a $1,000-per-plate fundraising dinner for his reelection. The pair shared another hug and photo op.63

Joe Wyatt, the congressman who sponsored the legislation that enabled Roy to receive the Medal of Honor, regularly mentioned his efforts in supporting Roy’s quest when he ran for reelection in 1982. At one debate with his opponent, Bill Patman, “tempers flared…,” observed a Victoria reporter, “when Patman made light of the importance of Wyatt’s effort to have El Campo veteran Sgt. Roy Benavidez receive the Congressional Medal of Honor.” Wyatt, trembling, pointed a finger at Patman and said, “I cannot believe, Bill, cannot believe, you would make that kind of remark. A distinguished and great American. And I worked for him and I’m proud of it.” Later, one of Patman’s supporters accused Wyatt of using Benavidez for his own personal gain. For a period of time, the level of support one gave to Roy Benavidez was a tangible political issue in Texas.64

Roy was aware of his status as a symbol, but he mostly stayed above the fray of partisan politics. In his first memoir, published five years after the Medal of Honor ceremony, he admitted, “I was a proper and convenient vehicle for the incoming administration to use as a demonstration of a new attitude of respect and understanding toward those who had fought and died in Vietnam.” Nevertheless, he always remained grateful to Reagan for the acknowledgment, even as he came to recognize that the theatrics of the ceremony provided political capital for the president.65

In the fall of 1981, Roy was busier than ever. In October, he went to West Point. The cadets were sitting down to dinner and listening to the typical announcements when a speaker called for their attention and began reading Roy’s Medal of Honor citation. “You had 4,000 people in the mess hall and it went silent,” recalled a member of the West Point class of 1982. “The citation just went on and on and you couldn’t believe one man could have accomplished this.” When Roy later spoke, “he had us spellbound,” remembered the cadet. “It made a huge impression on us. There wasn’t a dry eye. Of course, the applause was thunderous.”66

From West Point to elementary schools, Roy spoke to students of all ages. Back in Texas, he delivered lectures all over the state. He was particularly in demand in Austin, where the local branch of the American Legion helped organize events with local schools. During the 1981–1982 school year, Roy gave twenty-eight talks in Austin schools, interacting with tens of thousands of students. During one two-day stretch that October, he spoke to 7,500 students. After watching Roy speak, some of the students participated in essay contests based on a prompt asking them to describe what it means to be an American.67

After a 1982 lecture in Burnet, Texas, a special education teacher sent a stack of letters from her students to Roy. The kids all praised Roy’s speech, telling him how much they appreciated his courage and patriotism. Some of them shared lessons from his talk that they attached to their own lives. One young man wrote, “I was thinking about quitting school but you came along and after your speech I changed my mind.” Another wrote, “Your speech about quitting school help me a lot to stay in school.” Another student told Roy, “Your speech made me feel like a proud American.”68

One of the greatest highlights of 1982 for Roy came in November when he traveled to Washington for the dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Approved by Jimmy Carter in 1980 and completed with private funding in 1982, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial represented a watershed moment for the collective memory of the war. A group fundraising effort created the memorial, often referred to as “the wall,” uniting stakeholders in a new discourse that prioritized honoring veterans instead of rehashing the political fights of the 1970s that could never be fully resolved. The design of the wall was a highly contentious political issue, but the completed version, unveiled during a weeklong “National Salute to Vietnam Veterans,” helped refocus conversations about the war onto the sacrifices of those who fought. Many veterans appreciated the wall for the simple fact that it made them feel less invisible and more appreciated by a nation that had at times ignored their service.69

That November, Roy was asked by the governor of Texas to lead the state’s contingent of Vietnam veterans in a parade. Roy traveled to Washington, DC, where he led the Texas delegation in a demonstration of more than fifteen thousand veterans from across the country who marched down Constitution Avenue in front of a crowd of 150,000. The parade ended with the dedication of the wall, a twin set of two-hundred-foot black granite walls engraved with the names of the men and women who died serving their country in the Vietnam War. “I’m not the hero,” Roy told a reporter that day. “The names on that wall and those disabled in hospitals are the real heroes.”70

When Roy wasn’t on the road, he and Lala lived a simple life in their modest house with their three kids. Their love was the old-fashioned kind. They didn’t openly demonstrate physical affection in public, but they were deeply committed to one another, and they rarely fought. When they did, they argued in Spanish so the kids wouldn’t know; although Roy and Lala grew up in Spanish-speaking households, their own children didn’t learn Spanish, largely because Hispanic parents at that time were told to help their kids assimilate by speaking only English. The family went to church every Sunday, where they sat in the same section with their extended local family. They spent holidays at Aunt Alexandria’s house, the home where Roy and his cousins grew up. The entire extended family of sixty or more would pack into the small house, exchanging stories about Uncle Nicholas and sharing memories of their days on the road picking sugar beets and cotton. Roy had been away with the Army for most of the 1960s and 1970s, but he always remained close with his brother and cousins, who were successful members of El Campo society. His brother Roger worked as a realtor for thirty-nine years.71

Lala cooked family dinners, preparing beef and pork, even though she was vegetarian. She occasionally worked seasonal shifts at a local craft store, but that was the extent of her professional life. Lala otherwise didn’t work, nor did Roy want her to. She had her own circle of friends who played dominoes and bingo and took bus trips out of town. She was also involved with the children’s school, serving as a “room mom” who helped organize activities and supplies. When Roy was gone, Lala performed the daily work of raising three kids on her own.72

Denise, the oldest, remembers those times. She was impressed by the Medal of Honor ceremony, especially as it briefly elevated her status in school. “We were treated like rock stars,” she remembered of the night at the El Campo gymnasium. “Wow. That’s pretty cool,” thought the shy teen, who suddenly started getting autograph requests herself, despite being “just a nerdy freshman [who previously was] not getting much attention.”73

But it was also tough because their dad was so busy. After receiving the medal, Roy began to travel all the time. Lala was left home “helping us with homework,” remembers Denise, “taking us to various school activities that we needed to be [at], being the disciplinary person.” The family sometimes traveled with Roy, which they enjoyed, but even these trips were sometimes tarred by her dad’s celebrity status. Denise spent her sixteenth birthday at one of her dad’s speaking events in Louisiana. “I’m sixteen years old,” she remembered thinking, “and I don’t need to be in some swamp camp, Fort-something in Louisiana.… Of course I acted against it.” On another occasion, when Roy missed her birthday while traveling, Denise remembered a politician calling her to apologize for borrowing her dad. “Eventually I got over it,” Denise acquiesced. “It’s just going to be our lifestyle for a good while,” she remembered musing at the time. “It had its good moments and its bad moments.”74

Still, the kids were impressed by the way others responded to their father. Some people treated him like a movie star, asking for autographs and photographs. Others just wanted to shake his hand. Roy was big news in those days. When he boarded a flight, it was common for the pilot to tell the other passengers that Medal of Honor recipient Roy Benavidez was on the airplane, which always drew a cheer. During the flight, people would get out of their seats and walk over to greet him. It could get annoying, especially when someone would disrupt a family meal or private conversation to ask for an autograph. Roy rarely said no. He believed, one friend explained, that it was “his duty to oblige them with whatever they wanted.… Americans were his number-one priority, not his dinner.”75

Roy’s life had changed. This was a new existence. He was going to spend his days traveling around, giving talks to groups of admirers who would respond to him with standing ovations and long evenings of adoration. With all the trials Roy had faced, he was the happiest he had ever been. It’s hard to imagine his life without the Medal of Honor. It certainly would have been much worse without the recognition. Roy was a hero everywhere he went. People loved him. They wrote songs about him. He made them feel good. He told them about growing up poor and about his ascension to his heroic status. He was an outsider turned insider, a man who had ascended the height of American military lore.

To many in those audiences, America was great because it was a place that had provided such an opportunity for a kid like Roy. Certainly, some members of those crowds enjoyed a level of prosperity and stability bestowed upon them from birth. But Roy’s path to success had come from the other direction. He had once lived in a very different America, one in which he and his family couldn’t even sit in the front of a movie theater. Roy had earned his status not through the generosity of the country but rather because of his own willingness to sacrifice his life and health for a country that only later claimed him as one of its own. Still, Roy never made that point. Instead, he fed his audiences positive stories about the opportunities promised by life in the United States. In a way, his greatest gift to the nation, both in terms of what he had overcome as a boy and endured as a man, was his capacity to suffer for America. And the people loved him for it.