CHAPTER 12

GLORY DAYS

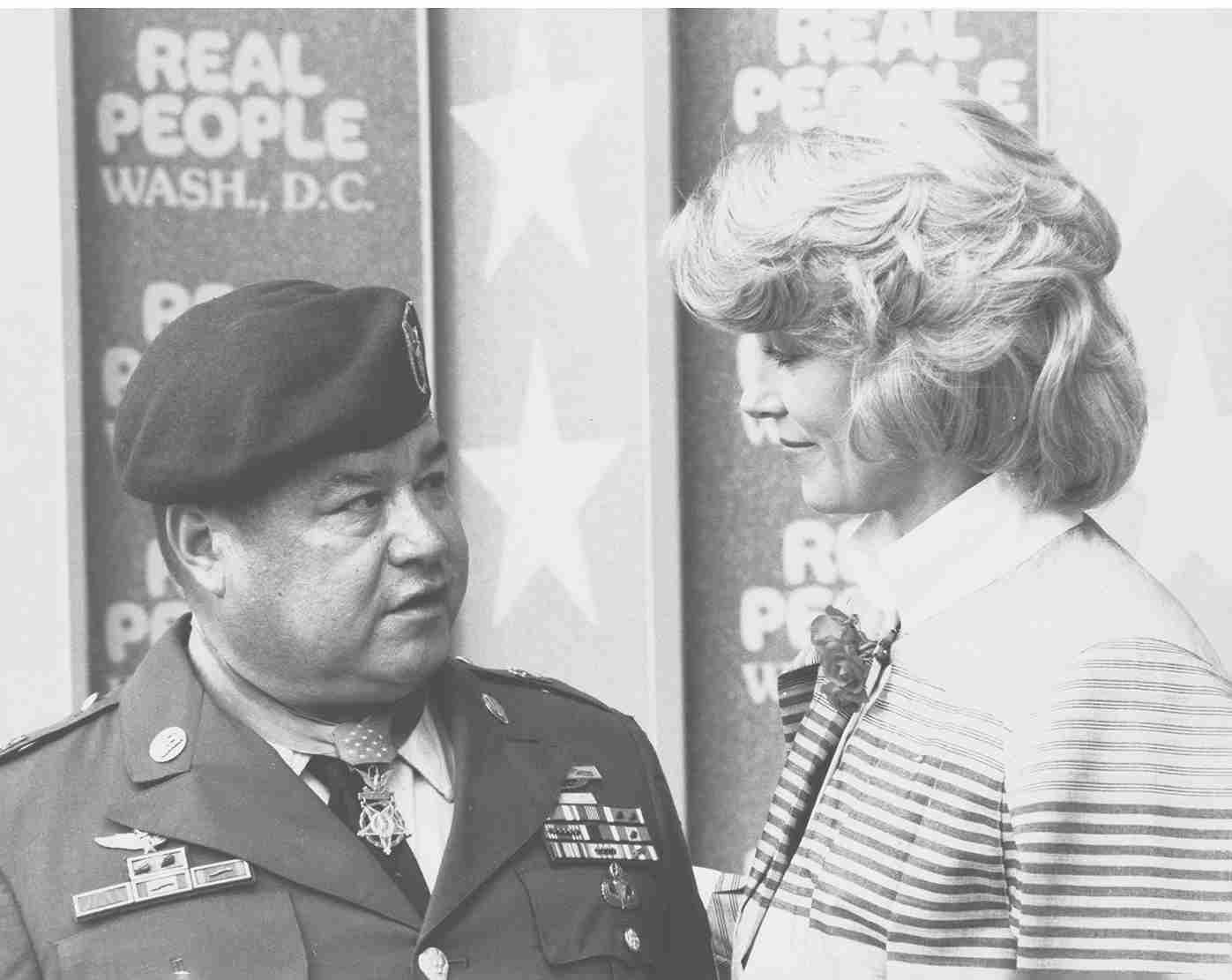

On November 9, 1983, Roy was featured in a Veterans Day episode of the primetime NBC television program Real People. Considered one of the first successful reality shows in the United States, Real People was a series of hour-long programs comprising short segments featuring fascinating everyday individuals. Most of the filming for Roy’s segment had been completed months earlier in El Campo and Washington, DC.1

The episode opened with one of the show’s hosts standing in the courtyard of the Pentagon recounting Roy’s 1981 ceremony as “a very impressive event commemorating an almost unbelievable story of courage and bravery.” The scene then changed to a clip of Roy greeting hospitalized veterans. “The men here are honored by his visit,” stated the narrator, “because to anyone in the military Roy Benavidez is a living legend.”2

This segment offered a general overview of Roy’s journey toward heroism—from a migrant worker to soldier—everything leading up to the combat story of May 2, 1968. A host interviewed Roy in his living room, where he sat in his armchair explaining his heroic actions. “There was no turning back,” he said. “You either fight, doggonit, or die right there. And I was gonna fight to the last damn minute I had.” The episode included interviews with the pilot Roger Waggie, Roy’s old commander Ralph Drake, and Congressman Joe Wyatt.3

Roy on Real People, 1983. Roy P. Benavidez Papers, camh-dob-017311_pub, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

The next portion of the episode highlighted Roy’s commitment to speaking in schools. “Roy feels that the honor of receiving the medal carries with it a great responsibility,” said the narrator. “To that end, he has traveled to schools all over this country to meet with and speak to the people he calls the future leaders of this nation.” It showed footage of an interaction between Roy and a student who asked, “When you were running through there and getting shot and everything, did giving up ever run through your mind?” “No honey,” Roy told her, “An American never gives up.” The room erupted in applause.4

Real People also arranged for a White House meeting between Roy’s family, a representative from the Reagan administration, and the hosts of the show. This portion of the episode was filmed during Roy’s SSDI fiasco. The final minutes showed clips from the White House, where Roy’s family met with Reagan’s director of public affairs. The show also included footage of the parade and ceremony marking the rededication of the Roy P. Benavidez National Guard Armory in El Campo. The last scene in Roy’s segment was of his family being honored on an outdoor stage in front of a live Real People audience who greeted them with a standing ovation. An estimated 13.4 million people watched the episode in its Wednesday prime-time slot. The episode was rerun twice the following year, including on the Fourth of July.5

The year 1983 marked the height of Roy’s fame. The Social Security saga of that year kept his name in the news and further elevated his status as a national hero. Roy’s case had been featured numerous times on every major network’s evening news program and in widely circulating dailies including the New York Times, Washington Post, and Los Angeles Times. Reader’s Digest had published a feature on him earlier that year, and millions saw the Real People episode. Roy was quite famous; not like a movie star or politician, but famous enough that millions of people across the country knew who he was. It was rare that he went somewhere in public without being recognized.

With his Social Security case settled, Roy went back out on the road, speaking to tens of thousands more people in 1984. There was no typical event—only Roy’s message remained the same. He would arrive at a venue and greet the organizers, who almost always wanted to shake his hand and pose for pictures. Sometimes, there would be a dinner. Other times, there would be drinks and socializing. The event might take place in a classroom, a cafeteria, or even a stadium. Roy spoke everywhere. Wherever he was, he was always ready to go with his life story and positive messages about patriotism and education.6

Roy was most popular in schools and military installations and at veterans’ events. He was busiest in Texas, especially around Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, and Veterans Day. A sampling of his 1984 events includes speaking at a Vietnam Veterans Day ceremony in New Jersey; appearing at a POW/MIA ceremony in Bay City, Texas; and speaking at the American GI Forum convention in June in Kansas City, where he spent two hours touring the local VA hospital. “I think it’s great he came here,” one of the patients told a reporter. Other events included a speech at the Dallas Rotary Club, flying to Washington for Hispanic Heritage Week, and another appearance in New Jersey to speak with college students. In November, he attended groundbreaking ceremonies for an armed forces reserve center in Corpus Christi that was dedicated in his honor. When a journalist asked Roy why he spent so much time on the road, Roy said, “The military molded me into the person I am today, so if the phone rings and somebody says, ‘I need you here,’ I leave my wife a note and go.”7

Roy kept track of his many appointments by writing them into the date boxes of a large monthly calendar. The 1984 version is filled with scribbles detailing the places and times of his events, along with the phone numbers of local contacts. The schedule is packed with speeches to all types of groups—Boy Scouts, students, veterans, and so forth. That year, he usually had two or three speaking engagements every week, mostly in Texas.8

Roy didn’t like to travel alone. By then, he had recruited a couple companions who drove him to events. One was the newspaper man Chris Barbee. The other was a new friend named Jose Garcia, whom Roy met in 1984 when delivering the keynote address at a LULAC event in Houston. Garcia was also a Hispanic veteran, and he had military security clearances that Barbee did not, which allowed him to travel nearly anywhere with Roy. Garcia was also retired, so he had a lot more free time than Barbee. Soon after they met, Roy asked Garcia to serve as his escort to some of the speaking events.9

Garcia worked as a handler of sorts for Roy. He was much better organized than Roy and helped plan trips and protect him from overbearing admirers. Roy was quite extroverted and grateful for all the attention he received. People fawned over him. They wanted to meet him, shake his hand, ask him questions, and even hug and kiss him. He spent hours after his talks meeting new people and signing autographs. Roy loved these interactions, but they consumed so much of his time, which could be a challenge if he had to run to another event. Garcia would pull him out of a crowd. He could say no when Roy was seemingly incapable of doing so himself. Roy was like a rock star catering to adoring fans, and Garcia served as his manager. When Roy had a hard time saying no, he could tell admirers, “Go talk to my escort.” Jose Garcia was happy to decline on Roy’s behalf.10

Garcia also watched out for folks who tried to take advantage of Roy. “Sometimes people would try to abuse him or take pictures with him and then use those pictures… for advertising for political reasons,” Garcia recalled. “So I needed to let people know that they could not abuse him in any way, shape, or form, especially women who wanted to get close to him.” Some people did shady things. There were cases of event organizers collecting cash at the door to hear Roy speak—ten or fifteen dollars a plate to hear Roy Benavidez over dinner—and then insisting they had no money to offer an honorarium. Some organizers invited Roy for one purpose and then asked for more of his time and energy upon arrival—piling on to Roy’s duties by requesting an extra meeting, talk, or meal. Garcia was there to advocate on Roy’s behalf.11

He also helped keep Roy out of trouble. A lot of military guys wanted to take Roy out drinking, and Garcia tried to make sure their activities didn’t get too out of hand. “Every time people took him to go sit down and discuss something, everybody was drinking,” Garcia remembered. “I mean, soldiers get together, they’re always drinking every time.” Garcia often stepped in to say no or “Don’t overdo it,” but Roy “drank sometimes a little bit more than I wanted to see him do.” The fact of the matter is that Roy liked to party a bit on the road; he liked to cut loose and socialize, especially with his fellow soldiers.12

With Chris Barbee, Roy had an agreement that “what happens in the field stays in the field.” They had a lot of fun on the trips. Roy loved meeting his admirers, and he was extremely social. But even beyond that, he enjoyed being out on the road, meeting interesting people and hearing their stories. “He was always going up and talking to people, you know,” Barbee recalled. Strangers would approach Roy, Barbee says, almost always asking “the exact same words: ‘Excuse me, sir. Aren’t you Sergeant Benavidez?’ or, ‘Aren’t you Sergeant Roy Benavidez?’” “It always amazed me how many people knew Roy, knew of Roy, and appreciated Roy,” Barbee said of his old friend. “It made him feel good.”13

Roy with Fred and Chris Barbee. Roy P. Benavidez Papers, camh-dob-017319_pub, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Roy had not sought the Medal of Honor to become famous. He had first begun fighting for it in 1974 and would gladly have accepted it then. It took seven frustrating and uncertain years for him to finally receive the commendation he deserved. One could argue that this itself was an injustice. Even the producers at Real People told their audience they were “bewildered why it had taken so long for him to receive his medal.” The delay also cost him thousands of dollars, both in personal funds he spent pursuing the medal and in the missing monthly Medal of Honor stipends he would have received throughout those years of delay.14

Yet the delay also cleared a lane to fame. Had Roy received the Medal of Honor in the 1960s or 1970s, he would have been just one of more than two hundred recipients from the Vietnam War, and his fame likely would have faded away during the military malaise of the 1970s. By receiving the medal in 1981, Roy got to be a hero in the long memory of the war, in the days when the nation once again started celebrating its military heroes without becoming overwhelmed by the collective national guilt and moral injury left in the wake of Vietnam.

In the early 1980s, writes historian Christian Appy, “there developed a powerful need to identify heroes who might serve as symbols of a reconstituted national pride.” The soldiers were pulled apart from the war, separated from the cause for which they had fought. The blame for the failures of the war was pinned on the politicians and not the military. As historian Patrick Hagopian has observed of the era, “the idea took hold that veterans’ and society’s wounds had to be healed together.”15

The tragic Vietnam films of the 1970s were replaced by a resurgence of patriotic movies like Rocky IV and Top Gun, films that set aside the complex issues of diplomacy in favor of a paradigm that celebrated America’s cold warriors. Part of the failure of Vietnam, audiences came to recognize, became the unwillingness to celebrate those who fought it. The veteran was the victim, the forgotten hero like John Rambo—the half–Native American Medal of Honor–recipient Special Forces veteran of the 1980s film franchise—who, after being shunned by his country, asked his former commander, “Do we get to win this time?”16

For some, Roy was the living embodiment of a nation that had turned its back on its troops. Like Rambo, he was a Special Forces veteran who had operated deep behind enemy lines under mysterious circumstances. And he had been the victim of a government that had not only sent him into harm’s way but also failed to later recognize his sacrifice. By the end of the decade some were openly calling him “The Mexican Rambo.” The difference was that Roy was real.17

The timing of Roy’s award also meant that he was alone. Other living veterans had received the Medal of Honor, but for the rest of Roy’s life, he was the most recent living recipient. And his ceremony had come at a turning point—in fact his ceremony was the turning point—for the resuscitation of the American military in the eyes of the public. As the admirers and media circled, Roy sought to further capitalize on his own story.

One could argue that Roy had always been self-promoting, ever since beginning his quest to pursue the medal. He doggedly pursued the medal for years, aligning dozens of influential allies who worked through more than six years of Army denials to constantly advocate for Roy’s Distinguished Service Cross to be upgraded to a Medal of Honor. But that pursuit was largely about proper recognition within the military. Roy mostly wanted only what he thought he had earned. He had certainly asked for the medal but not the attention that came along with it in the 1980s. The same could be said of the Social Security appeal. The fame that accompanied his story outpaced even Roy’s wildest dreams, and it began to reveal to him just how powerful his story could be. He always knew that his story was inspirational, but now he was coming to imagine it could also be profitable.

Although Roy enjoyed prominence, none of his activities generated a significant amount of income. He did most of the events and interviews for free. His travel was usually paid for by whoever made the invitation. Jose Garcia sometimes helped him secure an honorarium, but Roy was so committed to this type of service that he rarely pressed the issue of payment. But Roy’s speaking engagements were laborious. Public speaking was work, and traveling was hard. Roy’s commitments consumed countless hours of his life. He was willing to do it; in fact it made him happy. But at the same time, it was clear by 1983 that others were using Roy’s story for their own benefit, be it political or financial. He was grateful for the treatment and honorifics, but he also, understandably, wanted a bigger cut of the take. Plenty of others were clearly benefiting from his story in their magazines and television programs. Prompted by an endless stream of suggestions from friends and strangers alike, Roy began searching for ways to turn his life story into a book that he hoped could become a movie.

To do this, he needed help. Roy could work a crowd, but he didn’t know the first thing about authoring a book or making a movie. To accomplish this task, he tried to draw on some of the many connections he had made as a celebrity. One of the first people he contacted was Ronald Reagan, the movie star president. It was Reagan who had helped make Roy famous in the first place with the gaudy Medal of Honor ceremony. Based on the president’s reception to him, Roy thought they might be able to work together in the future. “Although we spent such a short time together,” Roy wrote to the president in 1982, “I still feel the closeness of those cherished moments.” When Roy first began considering a movie, he viewed Reagan as a natural ally. He wrote to the president seeking help with contacting a movie producer, and he asked Reagan to consider writing a foreword if Roy were to produce a book. But the president’s counsel declined, noting that “the President does not participate in any commercial ventures.”18

The following year, Roy wrote to the owner of a New York bookstore asking for help finding “a good ghost writer.” “I am told it will make such a good book and movie material,” he said of his life story. America’s growing Hispanic population, he argued, provided a natural audience. “There never has been a book or movie written by a Hispanic American MOH Winner. 22 million Mexican Americans and the rest of this country await such a good story.” He also wrote to the owner of a major New York literary agency asking if she’d be interested in representing him, but she declined, noting, “Your story is an important one, but I am currently unable to take on new projects.”19

Roy did not have the skills to write a book himself, nor did he have a solid understanding of the publishing marketplace. He made a good point about Hispanic audiences, but the New York publishing industry seemingly wasn’t very interested in attracting broad Hispanic audiences. The industry was, and remains, overwhelmingly white. White agents and editors sought books they believed white audiences would buy. Some very famous African American figures, especially Bill Cosby and Michael Jackson, used their fame to elbow their way onto bestseller lists, but mainstream publishers printed very few books about non-white subjects. There is no smoking gun that proves that race limited Roy’s commercial appeal, but the prevalence of other veterans’ stories—especially the mountains of books published by lesser-known white veterans—suggests there may be some connection. Regardless, Roy struggled to gain a foothold in the worlds of books and movies in Manhattan and Hollywood.

Speaking engagements came more naturally to Roy, and he continued these as he searched for more recognition in other forms of media. Roy understood how to craft his own persona with in-person audiences. He came across as an unassuming, modest soldier who just loved his country. Roy was a deeply intelligent man and a gifted speaker, capable of holding thousands of people on his every word. But he would begin his speeches by disarming his audiences, telling them he was a high school dropout and speaking with a thick accent and measured cadence. He’d recount his life story, starting with his parents and poverty-stricken childhood before describing his early days in the Army and eventually his time in Vietnam. Next, he would tell them how he recovered in the hospital, and then he’d talk about completing jump school training and joining the Green Berets. He didn’t need any outline or script because he was just telling the story of his life. All public speakers perform in some regard, but Roy’s persona tracked so closely to his actual personality and life story that he never strayed very far from who he truly was. He didn’t have to be anyone else when he had the Medal of Honor hanging around his neck.20

Roy almost always wore his uniform when giving speeches, allowing the decorations to establish his credentials. His ability to speak without notes made his lectures naturally conversational in tone. He was humble and kind, deflecting credit with lines like, “I am not a hero, the real heroes are those who never came back.” And he was ever so funny. He infused the grim details of his life with well-timed lighthearted quips that always drew a laugh from audiences. His humor was a gift to his crowds, a moment of levity in an otherwise weighty tale of poverty, war, and death. When explaining that he had mistakenly loaded three enemy soldiers on the aircraft during the May 2 battle, he’d pause and say, “I didn’t want to leave anybody behind,” and the audiences would erupt in laughter. The only thing that truly bothered him was when strangers asked, “How many people did you kill?” Of course, he didn’t know the answer. He never let on that taking so many lives bothered him. His emotions around those actions were private, discussed only with others who had had similar experiences. Otherwise, Roy’s message was simple, one wrapped in layered themes of patriotism and sacrifice that made his audiences feel good about their country. And he always told them, “I’m proud to be an American.”21

Roy’s brand was patriotism and service. His product appealed most to those who wanted to feel good about the United States of America. The message was always overwhelmingly positive, filled with sayings such as “An American never gives up” and “It’s great to be an American, so you can never do enough to help a fellow American.” He lived by the mantra of “Duty, Honor, Country,” and he committed to memory the patriotic poem “Remember Me?,” a sonnet about the fading reverence of Old Glory. He recited it often during his speeches.22

For those watching, Roy’s patriotism became the stuff of legend. In 1981, one columnist observed, “I understand this man… is so patriotic that he actually stands at attention and salutes even while watching television in his livingroom [sic], and the American flag is shown or the national anthem played.” “It’s hard to know,” wrote a Houston journalist, “just how to take a man so completely occupied with patriotism. You wonder if battle scarred his mind as well as his body. You wonder if he’s for real.” “That kind of intense patriotism,” wrote another Texas journalist, “just isn’t espoused by mainstream America anymore.” “You might meet someone as patriotic as Roy,” noted another author, “but nobody more patriotic.”23

Roy’s own life story carried immense patriotic power. He had every right to be bitter about the obstacles he’d faced along his journey, but he didn’t blame anyone or anything for the conditions of his youth, instead framing his early struggles as his own individual failure. Dropping out of school, he commonly told audiences, was a personal mistake. He told them that it was his fault, at times calling himself a “a fool” for doing so. But anyone who really knew Roy’s story understood that his leaving school was not his own fault. Of course, his audiences didn’t know that, making his capacity to absorb blame for his own disadvantage all the more remarkable. Roy made light of his obstacles in life to make his story more digestible for others.24

After establishing his supposed shortcomings, Roy praised the military for his salvation, telling audiences that the United States Army—and by extension the nation itself—gave him a chance in life after the mistakes of his youth. The story of his ascension at once gave hope to similarly disadvantaged youths and reassured the most privileged people in his audiences that America was a land of economic mobility. Roy’s story appealed to Reagan conservatives by emphasizing the opportunities America had to offer instead of dwelling on the inequalities he faced. People who support cutting federal programs for the poor so often commit themselves to the belief that those at the bottom simply don’t have the talent or drive to succeed. In fact, they even claim that the reason people are poor is because they have become too reliant on those same programs that provide basic necessities such as food and housing. But many Americans are poor not from a lack of talent or ambition but because their families didn’t have equal opportunities to build wealth. Racial segregation was not merely the separation of the races, it was also a systematic way of creating financial inequalities between white people and everyone else. It was the policies and legal practices of the United States government that made and kept Roy’s family poor. But Roy only gave America credit for helping to lift him up.

Roy also carefully sidestepped the issue of race, for both his audiences and himself. By virtually any measure, race had been the single greatest factor in creating the challenges of Roy’s family’s lives. Roy didn’t completely ignore the issue of race, but he repackaged it with sayings such as “True Americans do not look at the color of the skin, the only colors they look at are red, white, and blue.” For his audiences, his messaging softened the historical realities of race that, in truth, deeply affected the fate of his family.25

Roy also felt compelled to explain the origins of his mindset. Like the origin story of a politician or the conversion story of a prophet, Roy was called to explain the inspiration for his extreme patriotism. Like many politicians do, Roy said that the origins of his commitment to service were rooted in a meeting with a great American icon. For Roy, this was Audie Murphy, the famous World War II hero turned movie star. For years, Roy told audiences and reporters that he had become inspired to join the military by reading Audie Murphy’s book, To Hell and Back, and seeing the film as a child. He later recounted meeting Murphy while in the Texas National Guard, telling audiences that Murphy was his “idol and role model” and explaining that he was drawn to Murphy because they shared a similar background as poor cotton-picking kids from Texas.26

What Roy didn’t quite let on was that Audie Murphy was more than just a source of inspiration; he was a model—a poor Texas farmworker turned famous Medal of Honor winner. Roy wanted to be like him not only as a soldier but as a public figure. Audie Murphy had the book, the movie, and the fame, and Roy wanted the same. He essentially wanted to become the Audie Murphy of the 1980s, a newer, Hispanic version, repackaged and celebrated for another generation.

Roy’s approach worked in the speaking circuits. He was always in demand. There would be no film, and the books were years in the making, but he did successfully curate a very fulfilling life as a public speaker based on his accomplishments, messaging, and persona. Throughout the 1980s, the speaking engagements never stopped, and he spent much of the decade on the road, a traveling war hero for audiences across the nation.

Military folks particularly loved him. It was with them that Roy was most himself. They generally understood his experiences, and he seemed most relaxed in their presence. He counseled young men and women about their military careers, and he regularly visited VA patients during his speaking tours. One man who served as Roy’s guide at Fort Meade noted, “I have escorted him in the presence of general officers, senior civilian officials and tough warrant officers and enlisted personnel. It is always the same. They all hang on his every word, they salute him, they are moved to high emotion and they seek to learn from this quiet man.”27

In 1984, Roy’s travels included several visits back to Washington, DC, for military-related events involving President Reagan during the election year. In March, Roy attended a White House luncheon where Ronald Reagan awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Dr. Héctor Garcia, the founder of the American GI Forum. Roy was one of eight Hispanic Medal of Honor recipients invited to the event. They enjoyed a reception hosted by the president and were asked to weigh in on a speculative design for a new stamp honoring Hispanic American veterans.28

In May, Roy flew back to Washington to attend a Memorial Day tribute to the “Unknown Soldier” of the Vietnam War organized by the Reagan administration. An estimated 250,000 people lined the streets of Washington, DC, to watch the procession of a symbolic empty casket to Arlington National Cemetery, where an additional four thousand special guests, including Roy, attended a funeral service. Reagan offered a eulogy, for those “who served us so well in a war whose end offered no parades, no flags, and so little thanks,” and adorned the casket with a Medal of Honor. At the ceremony, a photographer snapped a picture of Roy wiping away a tear, an image that was picked up by the Associated Press and reprinted in newspapers across the country.29

In late October, Roy was back at the White House for an event in the Rose Garden where President Reagan unveiled a new stamp honoring Hispanic American servicemen and women. “I’ve always been aware of the many contributions Americans of Hispanic descent have made to our country,” Reagan said during the quick fifteen-minute ceremony. “It was my honor,” Reagan reminded the audience, “to have presented the Medal of Honor, the last one awarded to an Hispanic American, to Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez.” The new stamp depicted seven Hispanic Americans proudly standing in front of an American flag. It included four Hispanic veterans in uniform, three adorned with Medals of Honor, a woman in uniform, and two Hispanic youths on each flank, signifying the next generation of Latino leadership.30

The timing of the stamp ceremony was an obvious political stunt to many in the media. Reporters were skeptical when it was hastily announced a week before the 1984 presidential election. A widely syndicated column by journalist Dominic Sama noted, “Politics got mixed up in philately,” as “there were plaints that Reagan was tampering with philately to get some Hispanic voters in his column.” “The surprise move,” observed a reporter in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, “was, in part, an 11th-hour bid to increase the administration’s minority vote share.” New Jersey columnist George W. Brown called it “a bid for votes from the nation’s growing Hispanic population.” “Politics permeates even stamp world,” lamented a column in the Akron Beacon Journal. A Washington Post reporter also recognized the implications but argued that “earlier action might have provided greater political capital for Reagan.”31

The director of the White House Office of Public Liaison warned, two years earlier, that the president’s “initial upsurge [among Hispanics] has since reversed itself and is now declining at an alarming rate.” “Hispanics,” the same administrator warned that spring, “are beginning to view the Administration as racist and as one with little concern for the poor.” Some conservative Republican Hispanic devotees existed, but they were largely Floridians of Cuban descent. Republicans were very unpopular with the rapidly growing population of Hispanic voters in places like New York, Texas, and California. The Congressional Hispanic Caucus had formed in the late 1970s, and several major Hispanic organizations formed a lobbying group named the National Congress of Hispanic American Citizens. With their influence growing, the Reagan administration tried to appeal more directly to these groups to gain support among this crucial demographic.32

Roy didn’t say much publicly about politicians using him as political prop. He likely didn’t know the full extent. In any event, his enjoyment of the bright lights and big stages seemed to trump any concerns he may have had about the matter. He certainly never shied away from an event where a politician would honor him. Roy usually voted Democrat, but he worked with political leaders on both sides of the aisle, so long as they helped promote his message and, quite frankly, him. Whatever Roy may have said about Reagan during the Social Security conflict, he never missed a chance to be by the president’s side.

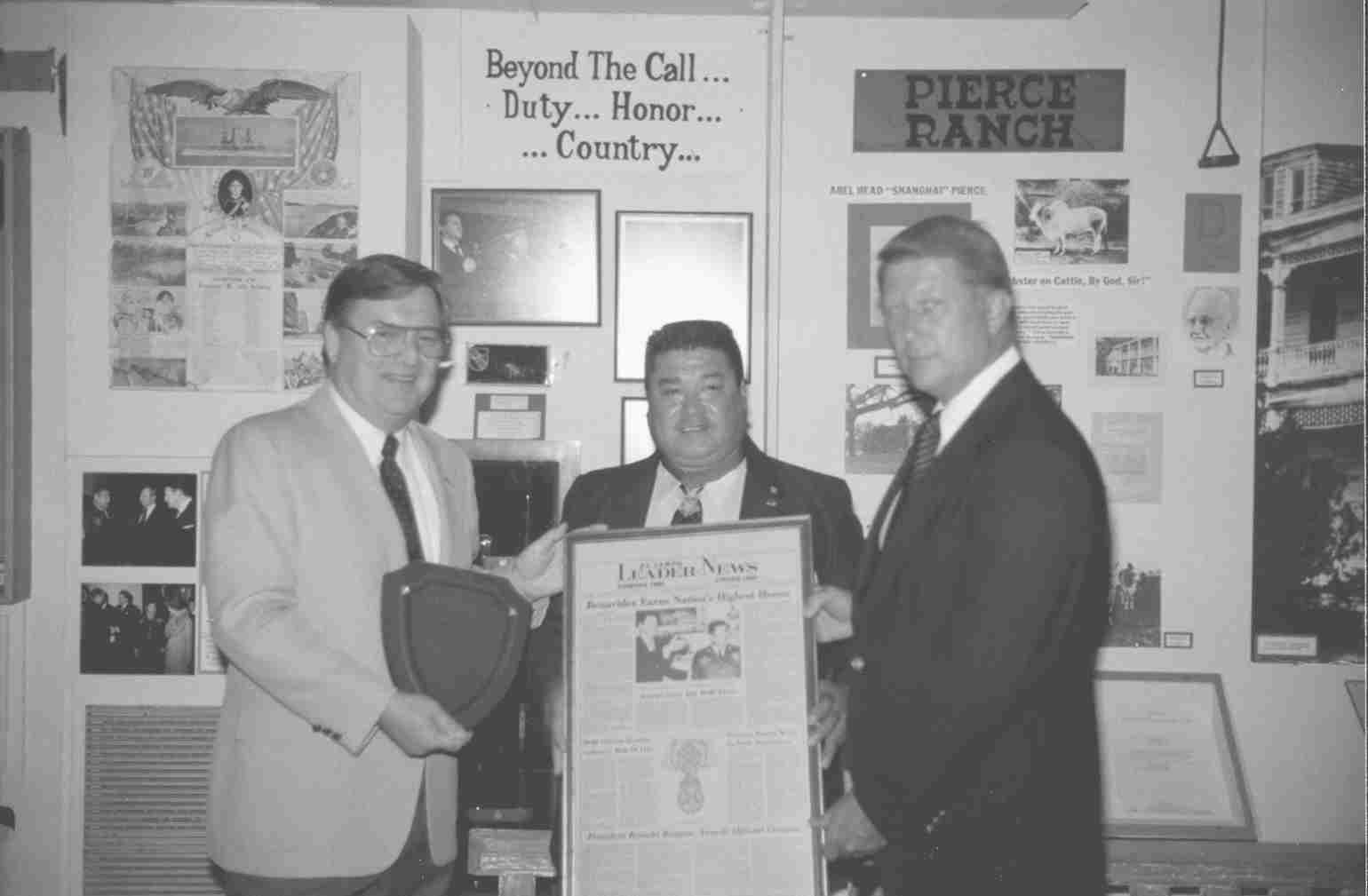

In January of 1985, Roy returned to Washington, DC, with Chris Barbee to attend Reagan’s second presidential inauguration. Every inauguration, the Presidential Inaugural Committee hosts the members of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, holding a special reception to honor these decorated veterans. Roy was close with many of the other Medal of Honor recipients and enjoyed these occasions with his friends. Barbee wrote about the event in the El Campo Leader-News. “Wherever we went,” he noted, “Sgt. Roy Benavidez was recognized, and respected.… Many asked for his autograph, others wanted to take his picture. Most just wanted to say ‘thank you.’”33

In 1985, Roy began openly talking about Vietnam-era foreign policy for the first time. He had previously avoided dealing with broad questions about the war, choosing instead to focus on his own individual experience and that of his fellow servicemen. But that spring, Roy made the rare move of telling an interviewer, “It wasn’t the soldiers who lost the war. It was the politicians and Congress.” “We weren’t defeated,” he said in a statement reminiscent of a Reagan talking point, “we just weren’t given permission to win.”34

The following year, Roy finally managed to publish an autobiography. The Three Wars of Roy Benavidez was published on Veterans Day in 1986. “Three wars” refers to Roy’s difficult youth, his fighting in Vietnam, and then his quest for the Medal of Honor. The book is a retelling of Roy’s time in combat and his pursuit of the Medal of Honor, interspersed with brief flashbacks to military training and his youth in Jim Crow–era Texas. Roy wrote the book with Oscar Griffin, a Texas-based journalist, businessman, and Army veteran who had won a Pulitzer Prize for local reporting in 1963. It was published by Corona Publishing Company, a small firm based in San Antonio. A press release quoted Roy as stating that writing the book was “like being in the Army again—we worked day and night.”35

The book provided another space for Roy to offer his feelings toward the war. It was a challenging subject. Roy’s criticisms, like those of a lot of miliary boosters in the 1980s, were aimed at unnamed politicians who, he said, denied the real soldiers the ability to win. But the policies he criticized were not merely political concerns or the Cold War theories like containment or the domino theory. He criticized the nature of the war itself. Here, Roy had to tread very lightly. The fact of the matter is that the problems with the war’s strategy were not solely the fault of political leaders. It was, after all, the Department of Defense and Roy’s superiors in the Army who designed and orchestrated much of the war. Roy’s most direct critiques were aimed at the South Vietnamese Army and the small cards with “Nine Rules” distributed to all American servicemen upon arrival in Vietnam, offering guidelines on how to “govern our conduct while in South Vietnam.” “The naiveté,” Roy wrote of the cards, “involved in their preparation is phenomenal.”36

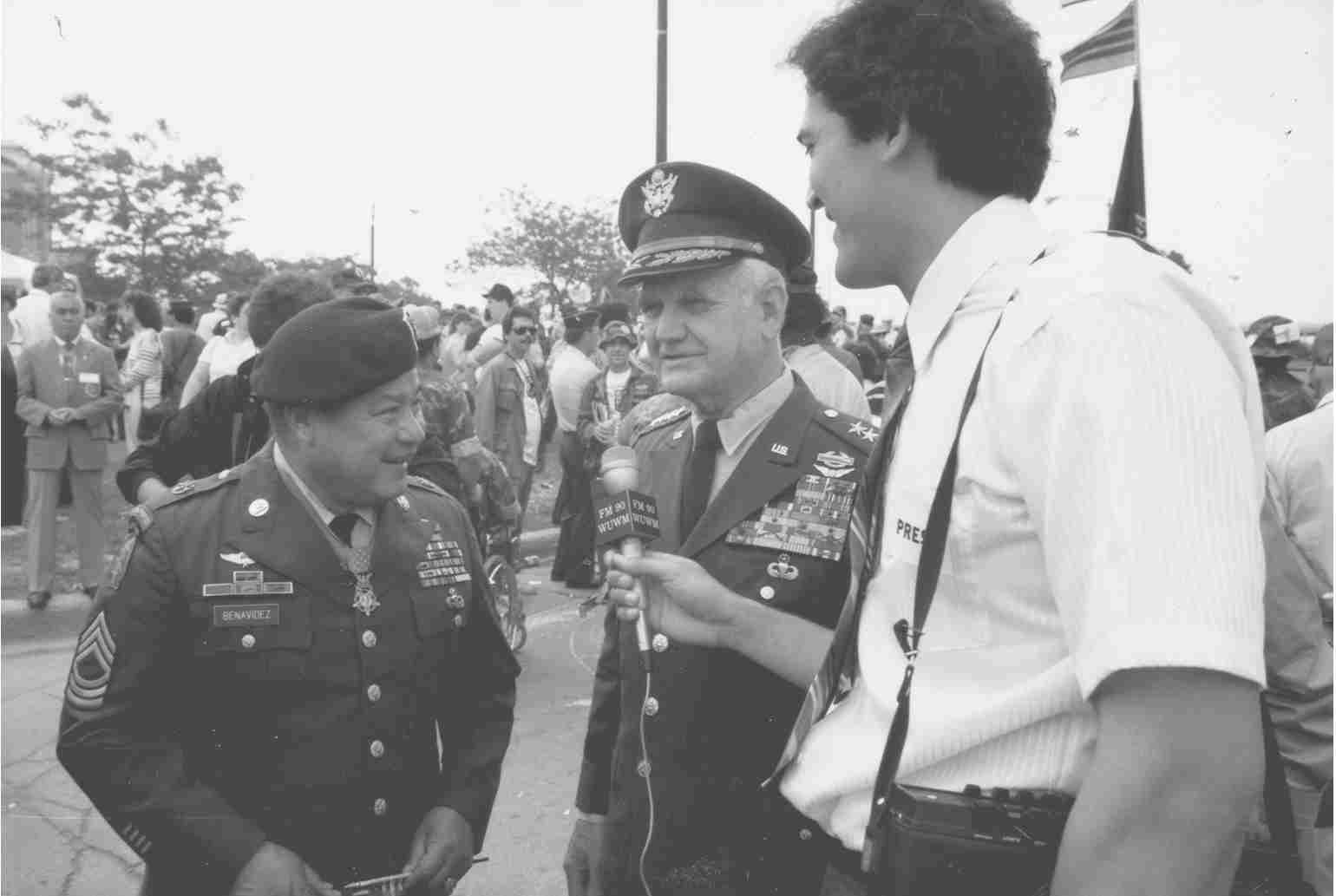

Much of the blame for the American limitations in Vietnam could have been laid at the feet of William Westmoreland, the United States military commander in Vietnam between 1964 and 1968. It was Westmoreland who influenced many of the misguided strategies that led to America’s failures in Vietnam. This was no secret, and Westmoreland was emphatically criticized by others. Westmoreland was also the person who designed the “Nine Rules” cards. While Roy indirectly critiqued Westmoreland by bashing the cards, he likely didn’t know that Westmoreland himself had ordered them to be produced and distributed. Roy would never have knowingly publicly criticized his former commander, a posture undoubtably influenced by his own personal relationship with Westmoreland. The men knew each other. They had crossed paths several times during the 1960s and again in the 1980s. In fact, a few months before Roy’s book was released, they marched together along with two hundred thousand other veterans at a “Welcome Home Veterans” parade in Chicago.37

Roy and William Westmoreland at veterans’ parade, Chicago, 1986. Courtesy of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

Like many military boosters of his day, Roy also had to deal with the challenging problem of celebrating the American military while addressing its shortcomings in Vietnam. To suggest that the military itself had failed in Vietnam would be to indict America’s armed forces as sometimes misguided, perhaps even immoral or weak. Like Reagan, Roy scapegoated politicians—the nameless, faceless softies who had limited America’s ability to win in Southeast Asia. He did so as he celebrated veterans for protecting American freedoms.

But neither Roy nor Reagan ever openly engaged with the question of whether America should have been in Vietnam in the first place. While many American citizens have long rooted military service and sacrifice in the name of freedom and liberty, the hard truth is that no one from Vietnam was ever coming to the United States to threaten any American’s freedom. The proof is in the past. The fall of South Vietnam and Cambodia to communist forces in 1975 did not present a direct threat to the national security of the United States or the individual liberties of its citizens. But that’s not something Roy ever wanted to explore or that his audiences would have liked to hear. It was much easier for him to question the tactics of the war than its entire premise.

For Roy, the matter was also so personal. He couldn’t possibly resign himself to the idea that his sacrifices and those of his friends had been made for the sake of a misguided cause. Psychologically, it would have been devastating to suggest that these sacrifices had been for naught. That would have been emotionally crushing and liable to cast doubt on the American military—the thing he believed in most in life. So Roy simplified his analysis, concluding that the war was lost by the idealistic politicians who cared too much about what other people might think. No one will ever really know what else Roy might have thought about the war. It is clear, however, why he could only critique it in a particular way.

The Three Wars of Roy Benavidez didn’t get a great deal of national attention. Kirkus Reviews recommended it for “lovers of war stories and meat-and-potatoes virtues,” noting, “It is direct and honest like its author.” But it also dismissed the prose as “forgivable.” The Associated Press ran an article mentioning the book, but its story read more like one of the many human-interest pieces on Roy rather than a review of his book. The book’s best review was published in the Austin American-Statesman, which praised Roy’s text for providing “details of one of the most incredible combat situations anyone has ever lived to tell about.” “Occasional overwriting aside,” the review concluded, “the book is a good read. And an inspiration for ordinary people.”38

A handful of local promotional events took place. Roy published a related op-ed in the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, emphasizing the important roles Hispanic Americans have played in America’s military. “I hope—no, I pray,” Roy wrote, “for the day that an American will simply be an American, and no hyphens will be necessary to describe that person.” The San Antonio Daily Star printed excerpts from the book, as did the magazine Vista, a Sunday newspaper insert distributed to newspaper subscribers in zip codes with large Hispanic populations.39

Roy received some positive letters in response to the book. One woman wrote, “In reading for nearly 20 years about the Vietnam war [sic], nothing that I have read has touched me quite the way your book has. Your courage and great humor shine on every page.” A man from El Paso praised, “I read your book and found it to be emotionally absorbing. It was also inspiring and epitomized the true American spirit.” Roy even received a note from Vice-President George H. W. Bush. “I have now read your story, and it really ‘came alive,’” Bush wrote. “I will treasure the volume you sent me.”40

But Roy’s book did not meet his own expectations. It did not lead to a film, nor did it sell a large number of copies. In the months that followed, he still searched for a connection to someone in the film industry, and he wrote often to his publisher, imploring the company to find ways to sell more copies. He even convinced Jose Garcia to write to the sergeant major of the United States Army to help him with sales, suggesting that the book should be “standard Army historical literature.” In 1989, an exasperated representative from the publisher responded to one of Roy’s inquiries, writing, “I’ve explained this several times before but I’m going to try one more time: we cannot force bookstores or any other retailer of books to order copies.”41

Meanwhile, Roy’s in-person public appearances carried on as they had for years. The Los Angeles Times called him a “professional military hero,” and the Austin American-Statesman noted, “The public won’t leave him alone.” Roy spoke at dozens of events, ranging from school assemblies to receptions hosted by small-town Chambers of Commerce and Rotary clubs. He carried around color eight-by-ten-inch photos, ready to sign for autographs. By 1989, his El Camino had 190,000 miles on it.42

During those years, Roy was still convinced there was going to be a movie made about his life. It wasn’t only him who thought this. People around him brought up the idea of a movie or documentary constantly. His audiences asked about it often, and his friends floated the idea through their various networks. In 1987, one of Roy’s old Green Beret buddies wrote to director Luis Valdez, whose film La Bamba, about rock star Ritchie Valens, had achieved mainstream success. “The Hispanic community desperately needs role models,” Roy’s friend asserted. At one point, Roy worked with a writer on a movie script that they submitted to the Department of Defense for official approval, but the military found several problems in the description of the combat and suggested major revisions. This effort ended shortly thereafter. There was seemingly always talk of some agent or director who might be able to get the movie made, and in the late 1980s, Roy constantly told his audiences and journalists across the country that a film would be produced. Alas, it was never to be.43

Still, the late 1980s saw some big highlights for Roy. In May of 1987, he was inducted into the LULAC Hispanic Hall of Fame during a black-tie event in downtown Los Angeles. A few weeks later, he traveled to West Point, New York, to visit the United States Military Academy. The events of that weekend included the dedication of “The Benavidez Room,” a conference room named in Roy’s honor. The following year, Roy traveled to Panama over the Fourth of July along with Willard Scott, the weatherman on NBC’s daily morning series Today. Perhaps the most special event of those years was Roy’s trip to Silvis, Illinois, a town where the local Mexican American community had renamed a street “Hero Street” in honor of a small neighborhood that had sent over one hundred men and women into the armed forces, almost all of them Hispanic. Roy spoke there and served as grand marshal of their 1987 Memorial Day parade.44

In 1989, Roy and Chris Barbee attended the presidential inauguration of George H. W. Bush, whom Roy had known since his Medal of Honor ceremony in 1981. President Bush once told a writer of Roy, “Every time I see him I get goose pimples, realizing all of the wounds he received while defending our country.… Barbara and I think the world of this man.”45

Roy addressing a group of young soldiers. Courtesy of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

Barbee was particularly excited by the inauguration of “a Texas president and we were Texans and all the Texans were struttin’ their stuff in Washington.” Roy was among 146 of the 225 living Medal of Honor recipients who gathered in Washington for the inauguration. Barbee was honored when the president-elect and his wife, Barbara, stopped to visit with Roy. He was also thrilled when Barbara Bush, “with a glow on her face,” flashed him a “Hook ’em, Horns” sign, the hand gesture of the University of Texas. “It was a grand inaugural for a Texan!” Barbee told readers back home. Roy sat on the podium during Bush’s swearing in at the United States Capitol. “I tell you,” he said to a reporter covering the ritual, “it puts a lump in your throat. It really does.”46

Roy was less active when in El Campo. While his days on the road were filled with receptions, parades, and ceremonies, at home he was more relaxed. He truly loved being a war hero, and he enjoyed the pomp and circumstance, the decorum and salutes, and the nights drinking and joshing with his military buddies. But it was also nice for him to be at home where he didn’t have to play that role. It was easier and more comfortable, and he’d be under less pressure. He could goof off and have fun with his family. His youngest daughter, Yvette, called him “very funny, a gentle giant.”47

Roy’s children entered high school age in the 1980s. Denise, the oldest, graduated from El Campo High School in 1984 and matriculated at Texas Lutheran College (now University) just outside of San Antonio, where she majored in music for three years before leaving school to start her own family. She later went back to college and earned her degree. Yvette graduated from El Campo High School in 1988, and Noel two years later in 1990. The 1980s were Roy’s kids’ teen years, the days of high school, first loves, and self-discovery. Roy was there for a lot of it, but it was Lala who raised their children during the many days he spent on the road. When he was home, he was involved, driving them to school, enjoying family dinners, and helping them with their teenage struggles, however big or small. “I could always go to him if I had an issue or a problem,” remembered Yvette, “and he always just knew the right things to say.” His greatest weakness as a father was that he was gone so much, but it was also that very role of a traveling war hero that provided him so much sustenance, both emotionally and financially, and peace of mind during the time he was home.48

Lala was a quiet but fierce woman. She commanded discipline and respect. Denise called her mother “strict” but noted that “she didn’t have to raise her voice at us. She had that look.… She wasn’t going to take any crap from anybody, and if you did let her down, if we made her disappointed in us, you could just tell by that look.”49

Like his Uncle Nicholas and Aunt Alexandria, who passed away in 1990 at the age of eighty-nine, Roy and Lala tried to teach their kids how to behave through their own example. They were exceedingly positive. They didn’t loudly argue or complain, and they didn’t gossip in front of their children. “They never said anything hateful or mean,” remembers Yvette, who insists “they had every right” to be bitter toward the local people who publicly criticized her father. “I never saw him yell at anybody,” Noel recalled. “I know he had disagreements, but it was just an adult conversation.” It set an important example that their children continue to follow.50

Roy and Lala also tried to instill in their kids a strong work ethic, a difficult task when neither parent has a traditional full-time job. Their children heard stories about Roy’s work as a child and of the difficult Army trainings. He didn’t bombard them with constant lessons from the military, but they perceived from his heroics and esteem that he was a very hardworking man. That work, Roy and Lala insisted, would pay off in the long term. “We knew the value of a dollar,” remembered Yvette, “and we knew that hard work will get you the finer things in life.” The Benavidez kids, like Roy decades before, were also schooled in the significance of their family name. “We knew we had a name that needed to be respected,” Yvette recalls, “and so I just didn’t want to bring dishonor to the name.”51

Noel had a tougher time with his dad than the girls. He was the youngest and the only boy, and Roy kept the closest eye on him. “He was strict,” Noel remembers of his dad. “Everything had to be done the right way.” Roy stayed on Noel about small things like proper manners and good grades. As someone who lectured kids about education and good behavior, he didn’t tolerate any signs of alcohol or tobacco use. If Roy heard about one of Noel’s friends drinking or smoking, he tried to forbid his son from hanging out with the boy. “You can’t ruin the family name,” Roy told Noel, echoing the lessons Uncle Nicholas once said to Roy.52

Noel did engage in some questionable behavior. As one of their family friends recalled, “Noel pushes his dad a lot.” Roy caught wind of him drinking on a couple occasions. Noel’s argument, he recalled, was “You do it. Why can’t I?” Of course, that didn’t exactly fly with the war hero. They butted heads, with Roy becoming angry at Noel anytime he heard rumors about his son’s misbehavior. Roy couldn’t possibly know all that Noel did in high school, but people around town would tell him if Noel was seen buying alcohol or attending a party. Noel remembered some rough early mornings when he was awoken by his father to answer for some accusation. “I don’t think my sisters had to deal with that,” Noel remembers.53

The greatest perk of being the youngest and only male sibling was that Noel had the pleasure of traveling with his dad. As Noel matured into his teenage years, Roy began to take his son along as his travel companion. The pair would mostly fly, but they also took some long road trips in Roy’s El Camino. Noel was fifteen when they drove to Virginia and spent nearly two weeks on the road. He credits the trip with helping him learn to drive.54

Roy liked to have some fun with his kids, sometimes at their own expense. He used to drive Yvette to school in an old red pickup truck that she found embarrassing. Roy “never bought anything brand new,” his daughter recalled. “He had this old jalopy of a truck, and I hated it because I was embarrassed.” She despised the old vehicle so much that she asked her father, “When you pick me up, can you pick me up in the car, please?” But when the school bell rang and Yvette walked out, “he’d be outside of his truck with the window down going, ‘Yoohoo! Yvette, over here!’ honking the horn.” “He was teaching me a lesson,” she remembered. “You should never be embarrassed at what you have.” Roy got a major kick out of such antics. He had enjoyed schoolyard pranks ever since he was a kid himself.55

As for Roy and Lala, they were close but independent. She had her own interests and group of friends. Plus, she often played the role of both parents when her husband was traveling. Still, they embraced traditional gender roles. Lala was a supportive wife who enabled her husband’s itinerant lifestyle, despite so many of those trips taking him away from the family. She respected his vision of his duty. In return, he trusted her with making major decisions about the children while he was away.56

They were also a very private couple. In public, they didn’t cover each other with constant kisses and hugs. Theirs was more of a quiet intimacy. Roy would flirt with her in front of the kids, teasing that she had almost dumped him when they were young. Denise remembered, “Dad would say silly things like he was trying to court Mom and Mom was trying to quit him,” referring to Roy’s pursuit of Lala in the 1950s. They would tease and flirt, sharing inside jokes about their past. They were old-fashioned. One could see it when it came time to dance. “My mother always loved dancing with him,” said Noel. “My mother didn’t dance with me at my wedding. She said the only man that she would dance with was my father.”57

The family loved having meals together. They were “really big breakfast eaters,” described Yvette of her parents. Lala did most of the meal preparation. When Roy did cook on his own, he made odd dishes that filled his children with wonder and disgust. Roy “liked anything” his daughter remembered. “He would mix pudding and ice cream and cereal and yogurt,” said Yvette. “I mean just weird things.… I think he’d do it more for the shock value.”58

There is little to suggest that Roy took much heed of his physician’s continuous orders to lose weight. For years, even before he left the Army, every doctor he saw said he was too heavy. The reasons were his diet, age, and disability. Roy loved to eat, and he liked beer, especially when he was hanging out with his best friends. He struggled to manage his weight, which was all the more difficult for a man with his injuries and travel schedule. But he was committed to his exercise routine. Almost every day that Roy was in El Campo, he walked the path around Friendship Park. People would see him out there every morning, rain or shine, in the heat or the cold. He was religious about walking that unshaded path around the playgrounds, picnic shelters, and ball fields. He’d spend hours there, walking and thinking. His walks were some of the only time he truly spent alone.59

Financially, Roy and his family were healthier in the late 1980s. After the problem with the Social Security office, Roy was never again removed from the disability rolls. Those payments, along with his Medal of Honor stipend, allowed the Benavidez family to live a fairly comfortable life in small-town Texas. El Campo was an affordable place to live, and they lived modestly. They only had one credit card, an American Express, and they always paid it off at the end of the month. “They had no debt,” Yvette remembered. “Their mentality was if we didn’t have money to get it, we weren’t going to buy it.” “They were very simple people,” recalled a friend. “They weren’t flamboyant in their decor or their furnishings.” When the kids really wanted an expensive item, they could ask for it for Christmas.60

Roy took trips with his family that were much different from his typical journeys. “My dad was actually a big proponent of family vacations,” said Yvette. They would pack up a red cooler with sandwiches and drinks and enjoy a family picnic at rest stops along the way. They went out west to Yellowstone and Utah. They also traveled to Big Bend National Park in western Texas. On other trips, they went to Alaska; Hawaii; Seattle; Washington, DC; and Philadelphia. Roy wanted them to “see the sights,” exposing his children to the iconic places of the country he loved so much.61

At home, Roy didn’t watch much television, mostly news shows like 60 Minutes and Nightline. He also enjoyed Benny Hill specials and some sitcoms. He didn’t like movies, especially those about the Vietnam War, except for the John Wayne film The Green Berets, which depicted America’s involvement in Vietnam as overwhelmingly positive. He listened to country music, having first fallen in love with the genre during his days as a migrant laborer. He particularly liked Johnny Cash, Charley Pride, and Freddy Fender, the Tejano country singer born in South Texas just two years after Roy. He also read a lot. “He always had a book in his hand,” remembers Yvette. It was common for him to read thrillers by authors such as John Grisham and Tom Clancy, whom he met on several occasions. Roy enjoyed comic strips like Beetle Bailey and Hägar the Horrible.62

He loved when people would visit. Those who knew him best stopped by El Campo whenever they were nearby. Roy “kept his inner circle very tight,” described one of his friends. But those who were in that circle received his full attention. When “it was time to visit,” recalled one of his buddies, “there was no outside obstacles like a television or the phones. It was all on whoever was visiting him.” They would sit and talk about current events or the military. He shared memories of combat with those who served. “He had a hell of a memory,” said one of his military buddies. Roy would often offer to help his friends and their families if they needed a letter of recommendation for a job or school. His name carried a lot of weight in Texas. As Roy once told a reporter, “I can’t snap my fingers and get something done, but it [his endorsement] does open a few doors.”63

His best friends at the time were other veterans, especially Hispanic ones who had been Airborne or members of the Special Forces. At this stage in his life, his best friend was probably Benito Guerrero, a veteran of the 82nd Airborne who was born near San Antonio the same year as Roy. Guerrero was also a decorated noncommissioned officer, like Roy. They had served together at Fort Sam Houston during Roy’s final months in the Army. The two men shared similar backgrounds based on their Texas upbringings and experiences in the Army and war. Both were very involved with veterans’ causes, and they became tight friends in the 1980s and 1990s, when they and other Hispanic Airborne veterans would spend a great deal of time at the Drop Zone Cafe outside of Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, an Airborne bar, popular with Hispanic veterans who would gather near the base to enjoy beers, tacos, and war stories.64

Roy’s home life was peaceful and he was surrounded by his family and close friends. He was happy and relaxed in his daily routine. He enjoyed the slow days in El Campo, running small errands and eating suppers with his family. At home, he could be himself and enjoy his family’s little world. But at any moment, the phone in the den might ring again, and the hero would pack up and head back out on the road.