The Mystery of the Missing Artefacts

by Tim Symonds

Date: August 1916

Location: A dungeon under the Dolmabahçe Palace, Constantinople

I stared up at the patch of blue sky visible through a tiny grille high up on the wall. I was a prisoner-of-war in Constantinople, left to rot in a dank cell under the magnificent State rooms of Sultan Mehmed V Reşâd, my only distraction a much-thumbed copy of Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent. Near-permanent pangs of hunger endlessly recalled a fine meal I enjoyed with my old friend Sherlock Holmes at London’s famous Grand Cigar Divan restaurant some years earlier. What I would now give for such a repast, I reflected unhappily. Every detail came to mind: The Chef walking imposingly alongside the lesser mortal propelling a silver dinner wagon. Holmes ordering slices of beef carved from large joint, with a portion of fat. I chose the smoked salmon, a signature dish of the establishment. For dessert, we decided upon the famous treacle sponge with a dressing of Madagascan vanilla custard. And a Trichinopoly cigar to top it off.

I should explain how twists and turns of fate had brought me to my present state. I shall not go into exhaustive detail. It is irrelevant to the bizarre case soon to unravel in a small market town in the English county of Sussex. Suffice it to say that, at the start of the war against the German Kaiser and his Ottoman ally, I volunteered to rejoin my old Regiment. The Army Medical Corps assigned me to the 6th (Poona) Division of the British Indian Army, which had captured the town of Kut-al-Amara a hundred miles south of Baghdad, in the heart of Mesopotamia. I had hardly taken up my post when the Sultan retaliated by ordering his troops to besiege us.

Five desperate months left us entirely without food or potable water. Our Commanding Officer surrendered. The victors separated British Field Officers from Indian Other Ranks and transported us to various camps across the Ottoman Empire. I found myself delivered to the very palace where, ten years earlier, the previous ruler, Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II, received Sherlock Holmes and me as honoured guests.[1] Now I was confined to a dungeon under the two-hundred-eighty-five rooms, forty-six halls, six hamams, and sixty-eight toilets of the magnificent building. It was clear from the despairing cries of my fellow captives that I was to be left in squalor and near-starvation until the Grim Reaper came to take me to Life Beyond.

The heavy door of my cell swung open. Rather than the surly Turkish warder bringing a once-daily bowl of watery grey soup, a visitor from the outside world stood there. We stared at each other. I judged him to be an American from the three-button jacket with long rolling lapels and shoulders free of padding. The four-button cuffs and military high-waisted effect reflected the influence of the American serviceman’s uniform on civilian fashion.

The visitor spoke first. “Captain Watson, MD, I presume?” he asked cordially. He had a New England accent.

“At your service,” I said warily, getting to my feet. I was embarrassed by the tattered state of my British Indian Army uniform and Service Dress hat. “And you might be?”

Hand outstretched, the visitor stepped into the cell. “Mr. Philip,” he replied. “American Embassy. A Diplomatic Courier came from England with a telegram for you. I apologise for the time it’s taken to discover your whereabouts. At the American Embassy, we are all acquainted with the crime stories in The Strand magazine written by Sherlock Holmes’s great friend, Dr. John H. Watson. None of us realised the Ottoman prisoner of war ‘Captain’ Watson was one and the same.” The emissary’s gaze flickered around, suppressing any change of expression at the fetid air. The pestilential hole had been my home-from-home for more than a month. “Not the finest quarters for a British officer, are they?” he smiled sympathetically.

I pointed impatiently at the small envelope in his other hand. “Is that the telegram?” I prompted. Mr. Philip handed it to me with a nod. The envelope carried the words “From Sherlock Holmes, for the Attention of Captain Watson MD, Constantinople. To be delivered by hand.”

“I have no doubt,” Mr. Philip went on, “that it’s to inform you that your old companion is working energetically through the Powers-that-Be to have you released and returned to England.”

Nodding agreement, I tore open the envelope. My jaw dropped. I glanced up at my visitor and returned my disbelieving gaze to the telegram. “My dear Watson,” I read again, “Do you remember the name of the fellow at the British Museum who contacted us over a certain matter just before I retired to my bee-farm in the South Downs?”

I remembered the matter in considerable detail. Towards the end of 1903, a letter marked Urgent & Confidential arrived at Holmes’s Baker Street quarters. It was from a Michael Lacey, Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum. Some dozens of small items in the Ancient and Mediaeval Battlefield department had gone missing, artefacts ploughed up on ancient battlegrounds or retrieved from graves of tenth or eleventh Century English knights and bowmen. They were of no intrinsic value. The artefacts had spent some years in storage awaiting archiving, but due to a shortage of experts, no work had been carried out. Would Mr. Holmes come to see the Keeper at the Museum and investigate their disappearance? Holmes waved dismissively. “Probably an inside job - perhaps a floor-sweeper hoping to augment a pitiful salary. It would hardly prove even a one-Abdulla-cigarette problem.” My comrade clambered to his feet, reached for his Inverness cape and announced, “I plan to spend today at my bee-farm on the Sussex Downs, checking my little workers are doing what Nature designed for them, filling jars with a golden liquid purloined from the buttercup, the poppy, and the Blue Speedwell.”

He looked back from the door. “Watson, don’t look so crestfallen. It’s hardly as if the umbra of Professor Moriarty of evil memory has marched in and stolen the Elgin Marbles. Kindly inform this Keeper of Antiquities that I haven’t the faintest interest in the matter. Refer him to any Jack-in-office at Scotland Yard.” His voice floated back up from the stairwell. “No doubt Inspector Lestrade will happily take time away from chasing horse-flies in Surrey to check on an owl job of such little consequence.” With a shout to our landlady of “Good day, Mrs. Hudson!” Holmes stepped into the bustle of Baker Street and was gone.

Now, inexplicably, ten and more years later into retirement, he wanted to know the man’s name. Not one word on my desperate situation. I turned the telegram over and wrote, “Dear Holmes, The name of the Keeper at the British Museum was Michael Lacey. Why do you ask? I recall how rudely you refused to take up the case. You said that after ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, no ordinary burglary could ever be of interest to you.” With blistering sarcasm I added, “Would you do me a small favour? When you can find a moment away from whatever you’re pursuing, get me out of here as quickly as possible? If the rancid slop doesn’t do for me, cholera will.”

The days passed with agonising slowness. At last, Mr. Philip returned. He told me the American Ambassador would shortly be making a demarche to the Sublime Porte to get me released. He handed me a second communication from England. I wrenched it open. The envelope contained a cutting from a Sussex newspaper, The Battle Observer. Below an advertisement for the Central Picture Theatre (The Folly of Youth), Holmes had marked out a photograph of a corpse lying in a field below ancient ruins. The photograph was attributed to a Brian Hanson, using a Sinclair Una De Luxe No. 2 - a camera I was myself planning to purchase using the savings from my Army pay, forced on me by my incarceration. The headline blared “Strange Death of Former British Museum Keeper”.

The report continued:

Early this morning, a body was discovered by local resident Mrs. Johnson, walking her dog across the site of the Battle of Hastings. An arrow jutted out of the deceased’s left eye. The dead man has been identified as Michael Lacey, former Head of Antiquities at the British Museum. The police were called and the body removed to the Union Workhouse hospital. It is not known what the deceased was doing in the field in the night. It is a spot seldom frequented after dark. Local legend holds the land runs crimson with blood when the rain falls. Ghostly figures have made appearances - phantom monks and spectral knights, red and grey ladies. Furthermore, each October, on the eve of the famous battle, a lone ghostly knight has been reported riding soundlessly across the battlefield.

The article ended with:

The police describe Mr. Lacey as a well-known if controversial and isolated figure in the area since his retirement to a house on Caldbec Hill, over ten years ago. He was rumoured to hold to the widely-discredited theory that the Battle between William of Normandy and Harold Godwinson of England did not take place on the slopes below the present-day ruins of Battle Abbey, but at a location several miles away. What remains certain is that William’s victory and Harold’s death from an arrow in the eye changed the course of our Island’s history, laws, and customs.

An accompanying note in Holmes’s scrawl said, “Come soonest. SH.”

* * *

A week later, a Turkish Major-General fell into the hands of British forces outside Jerusalem. A prisoner-exchange was agreed. By early October, I was back in London, greeting the locum at my Marylebone surgery. In a matter of hours, the Chinese laundry on Tottenham Court Road restored my Indian Army uniform, topee, and Sam Browne belt to pristine condition. I would wear the uniform for my visit to Holmes to avoid the attention of the ladies of the Order of the White Feather.

I tarried further in the Capital just long enough to visit Solomon’s in Piccadilly to purchase a supply of black hothouse grapes, and Salmon and Gluckstein of Oxford Street, where I stocked up with a half-a-dozen tins of J&H Wilson No. 1 Top Mill Snuff and several boxes of Trichinopoly cigars. The train deposited me at Eastbourne. I boarded a sturdy four-wheeler to engage with the mud.

The ancient County of Sussex is rich in historical features and archaeological remains, including defensive sites, burial mounds, and field boundaries. Holmes’s bee-farm was tucked in rolling chalk downland with close-cropped turf and dry valleys stretching from the Itchen Valley in the west to Beachy Head in the east. Some miles later a lonely, low-lying black-and-white building with a stone courtyard and crimson ramblers came into view. Holmes was waiting to greet me. At the familiar sight a wave of nostalgia washed through me.

* * *

While I fumbled for money to pay the cabman, Holmes drummed his fingers on the side of the carriage. The payment made, at a touch of the driver’s whip the horses wheeled and turned away. Holmes reached a hand across to my shoulder. “Well done, Watson,” he said, adding in the sarcastic tone of old, “Prompt as ever in answering a telegraphic summons.”

“Holmes!” I cried. “You might remember I was rotting in a dungeon in the Sultan’s Palace two-thousand miles away when your invitation arrived. I was lucky to find a British warship in Alexandria, or I might have been incarcerated a second time. The Mediterranean bristles with the Kaiser’s dreadnoughts and battle-cruisers.”

To mollify me, Holmes said, “We must ask my housekeeper, Mrs. Keppler, to bring you a restorative cup of tea. You will be offered a very civilised choice of shiny black tea or scented green.”

We seated ourselves in the Summer-house. I handed over the tray of Solomon’s black grapes and a share of the Trichinopoly cigars. My comrade passed across a large copy of the newspaper picture I had first seen in the Turkish cell. “I obtained this at a modest charge from The Battle Observer,” he explained. “Now, Watson, you’re a medical chap. I need your help. My knowledge of anatomy is accurate, but unsystematic. Tell me, what do you think?”

“Think about what precisely?” I queried, staring at the corpse in the picture.

“The arrow in his eye, of course,” came Holmes’s reply. “The local police say he must done it to himself,” he continued. “King Harold was shot in the eye by a Norman arrow. They suggest Lacey chose to die the same death, maddened by his failure to disprove the true site of the battle. The citizens of the town are in a hurry to close the case. They most definitely do not wish for unfavourable publicity ahead of the commemorative events.”

“Which events?” I asked.

“The eight-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Hastings,” Holmes replied. “In a week’s time. Hundreds of visitors are expected. Le Tout-Battle wishes to make a lot of money from them.”

“If you mean did the arrow cause his death, I can answer that straight away, Holmes. No, the arrow was not the cause of Lacey’s death. The angle of entry is quite wrong. It would have slipped past any vital part of the brain. In Afghanistan, I administered to one of our Indian troops who caught an arrow in the eye. He lived on for months and probably years.”

“Could it have been self-inflicted?” Holmes asked.

“Unlikely,” I replied. “In my opinion, he was already dead when the arrow was pushed into his eye.”

Holmes asked, “So the fear and horror on his face?”

“Already frozen into it.”

“Therefore the real cause of death?”

“Undoubtedly a heart attack,” I replied. “From fright,” I opined. “Something spine-chilling must have happened to Lacey on that isolated spot. Whatever it was, a rush of adrenaline stunned his cardiac muscle into inaction. Think of Colonel Barclay’s death in the matter of the Crooked Man. He died of fright. There’s a close similarity here.” I went on, “Dying of fright is a rather more frequent medical condition than you may imagine. I estimate one person a day dies from it in any of our great cities.”

Holmes rose quickly. “You have me intrigued, Watson. We must hurry. Drink up your tea. I may not have displayed the slightest interest in the Keeper of Antiquities and his little problems while he was alive, but in death he presents a most unusual case.”

“Hurry where?” I asked, bewildered.

“Why, to the British Museum, where else! It’ll be like old times. The last time I was there, I read up on voodooism.”

We went into the house. Holmes picked up the telephone receiver to order a cab. As he waited, he remarked, “A small point but one of interest, Watson. The police outside London often asked for my assistance whenever I was in the neighbourhood. I am a mere twenty miles from Battle. The inspector knows I am here, yet despite a mysterious death on his patch, no request to meet me has arrived at my door. What do you make of that?”

* * *

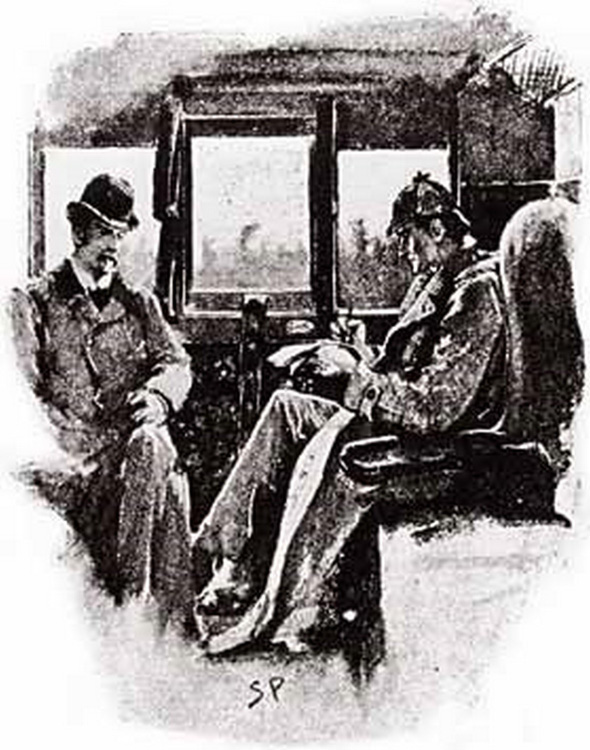

Within the quarter-hour a carriage arrived. As we jolted along, Holmes pulled out a packet of Pall Mall Turkish cigarettes and lit one, eyes narrowing against the smoke. He reached into his voluminous coat for the photographic print purchased from The Battle Observer. He stared at the image, puffing in thoughtful silence. “What is it, Holmes?” I asked at last. “Why the knitted brow and repeated drumming on your knee?”

“There’s something odd here, Watson. Something I quite missed at first. You have my copy of The Observer in your side-pocket. Can you pass it to me, please?” Holmes reached once more into his coat, withdrawing a ten-power silver-and-chrome magnifying glass. For a while it hovered over the newspaper. I was irresistibly reminded of a well-trained foxhound dashing back and forth through the covert, whining in its eagerness, until it comes across the lost scent...

Holmes gave a grunt. He passed the print and magnifying glass to me. “Tell me what you see,” he ordered. I stared down through the powerful glass.

“Nothing unusual, Holmes,” I said, looking up.

Holmes asked, “What about the grass under the corpse’s head?”

“The ground around the body gives no indication of a deadly struggle,” I replied. “Is that what you mean?”

He passed the newspaper back and commanded, “Now look again at the grass around the body as it appears in The Observer.”

Once more I looked through the magnifying glass. “Why, it’s nowhere near as clear as in the print, Holmes,” I replied. “In fact it’s quite grainy.”

“Precisely, Watson. Why would the grass be quite clearly defined in the print but look grainy when the same photograph appears in the newspaper? This is a three-pipe problem at the very least, Watson. I beg you not to speak to me for fifty minutes.”

Holmes flicked the cigarette butt out of the carriage window and produced his favourite blackened briar. I threw my tobacco pouch to his side and looked quickly out of the carriage window, blinking away a tear of happiness. The Sherlock Holmes of yesteryear was back.

* * *

After only one pipe, Holmes pointed at my Indian Army uniform. He shot me an unexpected question. “Watson, I presume sun-up would have had a vital role in your Regiment’s confrontation with Ayub Khan at the Battle of Maiwand. Isn’t that where you received an arrow in your right leg?”

“Left shoulder,” I replied. “And it was a Jezail long-arm rifle bullet, not an arrow.”

“My point is, Watson, did you become something of an expert on the daily motion of the sun?”

“I did,” I responded.

“To the point you can calculate the very moment of sunrise?”

“Yes, Holmes, but it’s far from as simple as you might think. First, you must decide upon your definition of sunrise - is it when the middle of the sun crosses the horizon, or the top edge, or the bottom edge? Also, do you take the horizon to be sea level, or do you take into account the topography? In addition, what of the Earth’s atmosphere? It can bend the light so that the sun appears to rise a few moments earlier or later than if there were no atmosphere.”

Holmes’s expression turned from one of interest to irritation. He tore the briar from his mouth. “Yes, Watson, yes,” he flared. “Take the arrow which stuck in your thigh. I consider a man’s brain is like an empty attic. We must stock it with just such furniture as we choose. I merely want to know whether - given a while with a note-book and pencil - you can calculate the exact time this photograph was taken?”

I replied, “If we say sunrise refers to the time the middle of the disc of the sun appears on the horizon, considered unobstructed relative to the location of interest, and assuming atmospheric conditions to be average, and being sure to include the sun’s declination from the time of the year-”

“Yes, yes, yes!” Holmes bellowed. “Take all of that into account, by all means!”

* * *

A telephone call from Holmes’s bee-farm ensured we were greeted at the Museum’s imposing entrance by Sir Frederick Kenyon, the Director. Sir Frederick was a palaeographer and biblical and classical scholar of the Old School. Our host led us to a small antechamber. The first drawer he opened revealed a glittering array of gold hoops and gold rivets, several silver collars and neck-rings, a silver arm, a fragment of a Permian ring, and a silver penannular brooch. Each was meticulously labelled. Sir Frederick picked out a sword pommel. “Mediaeval battles,” he announced. “This was Lacey’s life’s work - the Battle of Fulford, the Siege of Exeter... Never have I had a colleague who worked with such application. For years at a time, he would hardly leave to go home at night - that is, until...” He paused.

“Until?” I echoed.

Sir Frederick looked at Holmes. “I don’t know how else to put it - until Mr. Holmes failed to come to his help in finding the missing artefacts.” A flush of colour sprang to Holmes’s pale cheeks.

I interjected quickly, “Was it also from this drawer that the items of no intrinsic value were disappearing?” The Director shook his head.

“Not from here, no.” He pulled open a second drawer. “From here.”

The drawer was empty except for an envelope. It contained the letter I penned years earlier to the former Keeper of Antiquities, apologising for Holmes’s refusal to become involved in the investigation. I had reconstructed Holmes’s own words to read: “Mr. Sherlock Holmes sends his regrets. He is attending to his bee-farm in the South Downs and will not be taking cases for the foreseeable future.”

“The missing artefacts were in this drawer,” Sir Frederick continued. “Here’s where Lacey kept the more common or garden pieces found at various battle-sites. Broken sword-blades and the like. Miscellany too lacking in value or utility even for the local peasantry to pick up. Nevertheless he took the theft very hard.” Sir Frederick looked sympathetically at my companion. “Mr. Holmes, I understand your refusal. There wasn’t a gold or silver item or precious jewel among the lot.” Our host hesitated, then added, “Despite this, Lacey did seem unusually affected by Dr. Watson’s letter. His behaviour changed. He grew secretive. Now I reflect on it, it was as though he was developing a plan.”

Sir Frederick continued, “I noticed one other change... Other people’s fame began to obsess him. For example, when the antiquarian Charles Dawson declared the human-like skull he had uncovered near Piltdown to be the ‘missing link’ between ape and man, Lacey muttered something about making a discovery one day which would make his own name just as famous - not in anthropology but in the annals of English archaeology.”

I asked, “Did you have any idea what he meant?”

The Museum Director shrugged. “One day I came in upon him unexpectedly. He was bent over that table studying a drawing. Beyond saying it involved electrical theory, he would elaborate no further.”

“Electrical theory?” I heard Holmes repeat, asking, “Do you recall anything from the drawing itself?”

The Director shook his head. “I chanced only a quick glance before Lacey slipped it under some other papers. There were wires. I spotted a few words in French. I remember there were two large wheels, one at each end of the legs of a bipod. Oh yes, something about the wheels was odd. They weren’t upright like a dog-cart or other means of conveyance. They were flat on the ground.”

“What were the words in French?” I asked.

“‘Faisceau hertzien’,” came the reply. “I’m told that means wireless beam. My curiosity overcame me. “Lacey,” I said, ‘I’d be grateful if you kindly let me in on this secret of yours!’ But all he muttered was something about unexploded bombs. Then he got up from the table and said he’d been meaning to talk to me. About retirement. He said if Europe’s greatest Consulting Detective couldn’t be bothered to look into the theft of artefacts from the British Museum, his faith in human beings was gone. A month or so later, he handed in his resignation and quit.”

* * *

The great doors of the Museum shut behind us. I hailed a motorised hackney. “Waste of time coming all the way here, wasn’t it, Holmes!” I remarked, “I can’t say we learnt much about anything.”

Holmes’s eyebrows arched. “To the contrary, Watson, I think we learnt a very great deal. Take Lacey’s violent reaction when he received your letter. Even to hand in his resignation! I’d have expected him to be exercised if the priceless gold and jewelled artefacts had been filched. None of those went missing, despite being right next to the drawer containing quite ordinary relics. You’d have thought even the most common or garden sneak thief in something of a hurry can spot the difference between a gold torque and a rusty link from a dead Saxon’s chain-mail armour.”

The cab turned in response to my wave and halted at the kerb in front of us. Once seated, Holmes continued musing. “Why would the loss of a few worthless battlefield gew-gaws generate such a clamour from the Keeper?”

“Monomania perhaps?” I answered. “As you know, there’s a term the French novelist Honore de Balzac invented, ‘idée fixe’, describing how an obsession may be accompanied by complete sanity in every other way.”

Holmes asked, “What do you make of the other curious matter, the machine depicted in the blueprint? A bipod with two large wheels flat against the ground?”

“I haven’t the faintest idea, Holmes, nor why the subject of unexploded bombs would come up at the British Museum.”

“True,” Holmes responded thoughtfully. “It’s certainly an odd subject for a Keeper of Antiquities.”

We reached Victoria Station. The train trundled over the Thames. We were on our way back to Sussex. The last low rays of the setting sun sparkled against the cross atop the great dome of St Paul’s Cathedral.

* * *

After a lengthy walk in Holmes’s woods and fields that evening, we returned to the farmhouse. I struck a match on my boot and put it to the fire laid earlier by Mrs. Keppler to ward off the country damp. The ancient hearth blazed up as heartily as in our days at 221b Baker Street, fuelled from the abundant oak, the Weed of Sussex, rather than the sea-coal in our London fireplace. I opened my note-book and said, “Holmes, you asked where the sun was at the instant the camera shutter was released. Judging by the shadows in the photograph, I believe the photograph was taken when the geometric centre of the rising sun was eighteen degrees below low hills to the south-east. Around 6:40 a.m. was the first moment there would have been enough light.”

My companion absorbed this in silence. A few minutes later he asked in a sympathetic tone, “If Captain Watson of the Army Medical Department were to consult Dr. John H. Watson, MD, at the latter’s renowned medical practice in Marylebone, would Dr. Watson tell the Captain he has fully recovered from a frightful ordeal in Mesopotamia, followed by incarceration in a Turkish dungeon?”

“Thank you, Holmes,” I replied, touched by this rare concern. “You may take it the Captain’s heart would be certified as strong as that of the proverbial ox. Daily walks on the warship returning Captain Watson to these shores, combined with the fine food of the Naval Officer’s Mess, completely restored him.”

“Excellent!” my companion exclaimed, a trifle enigmatically. He leaned with his back against the shutters, the deep-set grey eyes narrowing. “Watson, we hold in our hand the threads of one of the strangest cases ever to perplex a man’s brain, yet we lack the one or two clues which are needful to complete a theory of mine. Ah, I see you yawning. I suggest you retire. I shall tarry over a pipe a while longer to see if light can be cast on our path ahead.”

The country air and the warmth of the log-fire had taken their effect. I hadn’t the slightest idea what Holmes was up to or whether or how the strength of “Captain Watson’s” heart could have anything to do with the present perplexing case. I fell into a comfortable bed and a restful sleep.

I was dreaming of I know not what when a loud rat-tat-tat came on the bedroom door. “Watson!” Holmes called out. “We must throw our brains into action. Dress quickly!” I opened an eye. Through the window, Venus and Mars were in close conjunction, bright in an otherwise cloudy night sky. “What is it, Holmes?” I returned indignantly. “Can’t it wait till dawn?”

The door flew open. My impatient host entered, dressed for the outdoors in Norfolk jacket and knickerbockers, with a cloth cap upon his head. “Watson, the genius loci. As you know, I’m a believer in visiting the scene of the crime. It is essential in the proper exercise of deduction to take the perspective of those involved. I have just returned from Battle. I must return there with you straight away. Just one thread remains, my dear fellow. You are the one person who can provide it.”

Scarcely an hour later, Holmes and I stood side by side on the spot where William the Conqueror’s knights crushed King Harold’s housecarls and his Saxon freemen. Holmes flapped a hand over a patch of grass. “I estimate the body lay here. Watson. How long before the geometric centre of the rising sun reaches eighteen degrees below the horizon?”

I looked to the south-east. “Not more than five minutes,” I replied, adding, “May I say I’m at a complete loss to know what in heaven’s name we’re doing here, Holmes. The dawn hasn’t even...”

“Then Watson, you must have your answer!” Holmes shouted. “Turn to face the Abbey!”

I whirled around. A terrifying apparition burst upon my startled gaze. With no sound audible above my stentorian breathing, a knight in chain-mail astride a huge charger was flying down the slope towards me, a boar image on his helmet, on an arm a kite shield limned with a Crusader cross and six Fleur De Lis. Behind, half-a-dozen cowled monks rose out of the ground, menacing, crouching, uttering strange cries. I broke into a cold, clammy sweat. My muscles twitched uncontrollably. I felt I was about to crash to the ground. The immense horse and rider passed by in a second, dashing on until the pair merged with the spectral mist rising from a clump of bushes a hundred yards down the slope. I turned to face the ghostly monks. There was no-one there. It was as though a preternatural visitation had returned to the Netherworld with the first shafts of the rising sun.

I dropped to all fours, dazed. Holmes’s voice came to me faintly, as though from a distant shore: “Watson, my dear fellow, are you all right? You’ve had a terrible shock.” The familiar voice brought me back to sanity.

“We can agree that I have, Holmes,” I panted. In the same reassuring tone, Holmes went on, “The phantoms have gone, my dear friend. They’ve returned to their rest. They will not be back until the next anniversary of the Battle of Hastings.”

I looked around the empty sward. “Where on Earth...?” I began.

“Tunnels, my dear fellow,” Holmes answered. “Monks and other ecclesiasticals. Landed Gentry. Knights Templar. Abbots. All particularly given to tunnels.”

The terror I endured for those few seconds was dissipating. Holmes looked at me closely. “Again I ask, are you all right, my dear fellow?”

“I am nearly recovered,” I said. “I appreciate your evident concern, Holmes, but you are clearly not an innocent party to this strange event. I deserve and demand an explanation.”

Holmes seated himself on the ground at my side. “Two clues put me on a scent, Watson. First, the trace evidence around us here.” His finger described an ellipse following the trajectory of the ghostly horse as it galloped down to the swamp. “Look there, and there,” he ordered.

I stared at the series of depressions in the grass. “But Holmes,” I protested, “while those indentations may fit where a horse’s hooves would have landed, they are both too shallow and too square for the marks of a horse ridden at speed!”

“My dear Captain Watson, I take it even in your service in the Far East you failed to hear of mediaeval Japanese straw horse-sandals known as umugatsu? They were tied between the fetlock and hoof to give traction on wet terrain and to muffle the sound of the hooves, and to deceive by eliminating the deep cuts hooves would inflict on damp earth. I think we can credit the local schoolmaster for his scholarship.”

“Nice touch. The Crusader shield too,” I remarked sarcastically, “when you consider the first Crusade didn’t commence until thirty years after the Battle of Hastings.”

I fingered my pulse. It was returning to normal. “And the second of two clues, Holmes?”

“The second lay in the difference between the print I purchased and the same photograph as it appeared in The Battle Observer. The editor wanted only the corpse’s face and the arrow. Therefore, Hanson enlarged the middle of the print. This brought out a granulated effect in the grass under the head. But why? Why was there any graininess about the background at all? Why weren’t the blades of grass as much in focus as the face and arrow?”

“Holmes,” I responded, “I have given it some thought. Forgive me if what I’m about to propose sounds absurd, but I’m very far from being unacquainted with cameras, as you know. The only explanation is the camera must have been positioned much higher up than if held by someone standing on the ground in the normal way. Getting the face in precise focus at the greater distance would mean anything deeper would be less in focus. This effect would show up most when the photograph was enlarged.”

“The very conclusion I came to myself, Watson!” my companion exclaimed, rubbing his hands in delight. The occipitofrontalis muscles of my forehead wrinkled. I asked, “But why would Hanson stretch his arms high over his head to take the photo?”

“He wouldn’t,” came the response. “He didn’t need to. He was seated on a horse. The knight was none other than The Observer photographer himself.”

* * *

I waved at the field stretching away above us. “Holmes, how in Heaven’s name did you get them to cooperate?”

“Not eight hours ago, I paid Hanson a visit,” Holmes replied. “He admitted everything. I told him he and his co-conspirators could be in mortal danger, accused of murder, and that my silence was not safeguard enough - others may yet make the same deduction. He said ‘I’m the one who thought up the caper. If anyone is to meet the hangman, it should be me.’ I told him I had something in mind. He and the monks were to reassemble here before dawn today.” Holmes tapped his watch and raised and dropped an arm. “At my signal, the knight was to charge straight at the man in a captain’s uniform at my side. The monks were once again to spring up like dragon’s teeth, yelling any doggerel they could remember from schoolboy Latin.”

The explanation jolted me to the core. “Holmes!” I yelled. I broke off, breathing hard. “Holmes,” I repeated, “I once described you as a brain without a heart, as deficient in human sympathy as you are pre-eminent in intelligence. Are you proving me right? Are you saying that despite Lacey’s frightful death, you deliberately exposed me to an identical fate?”

“Yes, my dear Captain,” Holmes broke in, chuckling, “I did. You must remember I took the precaution of checking on your health with a Dr. Watson famed on two continents for his medical skills. He pronounced your heart strong as an ox. Who am I to dispute his diagnosis?”

“And if the good Dr. Watson had made a misjudgement?” I asked ruefully.

“High stakes indeed, Watson,” came the rejoinder. “I would have lost a great friend, and a hapless crew of locals their best witness, leaving me bereft and them open to a second charge of murder!”

My legs still felt shaky. “Holmes,” I begged. “Why are you so adamantly on these people’s side?”

“Think of this small town, Watson,” my comrade began. “Eight-hundred-and-fifty-years ago, when Duke William crossed the Channel, there was no human settlement here, just a quiet stretch of rough grazing. Look at it now! Without the battlefield, it would be nothing, a backwater, a small and isolated market-town. Imagine Royal Windsor without the Castle, Canterbury without the Cathedral. Visitors to this battleground provide the underpinning of every merchant on the High Street, the hoteliers and publicans, even The Battle Observer itself, dependent on advertising Philpott’s Annual Summer Sales and the like. The mock monks and a spectral knight on horseback can fairly be accused of one thing - trying to protect their livelihoods. If visitors stop coming, the hotels die. The souvenir shops die. The cafés and restaurants close.

“Napoleon greatly incensed the English by calling us ‘a nation of shopkeepers’, and England remains a nation of merchants. All her grand resources arise from commerce. What else constitutes the riches of England? It’s not mines of gold, silver, or diamonds. Not even extent of territory. We are a tiny island off the great landmass of Eurasia.”

Holmes pointed to where ghostly horse and rider had disappeared. “Have you recovered enough to walk down to that clump of bushes? I anticipate we shall find something there of extreme interest.”

At the bottom of the slope, a small bridge took us to a patch of marshland dotted about with bushes and reeds into which horse and rider had disappeared. Holmes’s former quick pace slowed like the Clouded Leopard searching out its prey. With a grunt of satisfaction, he darted forward, calling out “Come, Watson - give me a hand!” A pair of wooden spars jutted from the mud. A spade half-floated on the mud a few feet beyond. We dragged the contraption to a patch of dry ground. It was the physical embodiment of the blueprint the Keeper of Antiquities had tried to hide at the British Museum. Held upright, the bipod was perhaps three feet in height. It was exactly as described by Sir Frederick: The two wheels were not wheels of a small cart, but circles of wood and metal lying flush with the ground, some twenty-four inches apart. A set of wires led to a half-submerged metal box filled with vacuum tubes and a heavy battery.

I pointed. “Holmes, those are Audion vacuum tubes. I’ve seen them used in wireless technology. This must be the secret invention Lacey hinted at.”

“If he had not built it, Watson,” Holmes responded, “Lacey might still be alive.” He continued, “I pondered long and hard about ‘Faisceau hertzien’, and the reference to unexploded bombs. Then by chance, my brother Mycroft called to say he had been seconded to the War Office for the duration. In the greatest confidence, he told me the French 6th Engineer Regiment at Verdun-sur-Meuse has been developing a machine using wireless beams to detect German mines. Somehow Lacey must have heard about it. He realised he could adapt it to search for metal artefacts at ancient battlegrounds.”

“But, Holmes,” I asked. “Why use it on this field? After all, if Lacey’s intention was to disprove the battle took place here...”

“It was Lacey’s ‘idée fixe’,” my companion interrupted.

He pointed at the spade. “He criss-crossed these fields at night using a device which could spot even a silver penny dropped nine centuries ago. With it, he was able to detect and remove every metal artefact left by Duke William’s and King Harold’s men. Lacey may have found nothing whatsoever, not even a piece of rusty chain-mail, proving the battle never took place here, or he was clearing it of anything traceable to 1066 - in short, planning a great evil against the noble profession of Archaeology. At a moment of maximum publicity, he intended to denounce the town’s claim to the battle-site. He did not give a thought that the town’s prosperity would come to an abrupt end. Even The Battle Observer would go out of business. But one recent moonlit night, Brian Hanson saw this phantom-like figure slowly across the landscape. He recognised Lacey. He guessed what he was up to. The townsfolk had to work fast.”

“Should we go to report our findings to the local police, Holmes?” I asked.

“By no means,” came a firm reply.

I turned to stare at my companion. “But... but surely, now we know-”

“Watson, we need do nothing but wait to see if the matter progresses or simply dies away. If the latter, a kindly fate has taken its course. If the former, thanks to you no jury of twelve good men and true will convict for murder.”

“How can that be, Holmes?” I asked, “when indisputably their actions caused the death of a man. How can they escape the hangman’s noose?”

“Bear in mind,” Holmes began, “our motley crew of locals didn’t have murder in mind. They rose up out of the ground dressed as the disquieted souls of long-dead Benedictine monks and inadvertently caused Lacey’s heart to give way. Their plan was to frighten him off and fling his infernal contrivance and spade into the swamp. That that was their intent is the more credible, thanks to your survival. They now have a good case to plead Mens rea-no mental intent to kill. At worst manslaughter, not murder.”

“The arrow?” I asked.

“Admittedly a barbarous act,” Holmes replied, “but the man was already dead. Hanson hoped to confuse the coroner, to make him conclude the arrow caused the stricken expression on the corpse’s face. Otherwise, alarm bells would ring, and a case of murder arise.”

Now mollified, I asked, “And who would want to associate the vile crime of murder with these dear old homesteads set in a smiling and beautiful countryside?” I continued lyrically, “I could hardly bear the thought such a peaceful and pleasant English market town could harbour a murder gang. Another case resolved, Holmes. Let us leave the good people of Battle to their commemorative preparations and repair to our favourite eatery deep among the Downs - in short, visit the Tiger Inn and partake of a hearty lunch.”

* * *

We heaved the spade deeper into the marsh, and marked the unexploded-bomb detector’s location for retrieval by Mycroft Holmes’s agents at a later time. As we walked back across the small bridge, I said, “There’s a matter you have not explained. Why did the Keeper of Antiquities react in such a choleric way to your refusal to investigate?”

“It was quite worthy of arch-criminal Moriarty of old, Watson, a most devious ploy. A snub was precisely what Lacey wanted. I should have smelt a rat by the way he worded his request - ‘I shall of course understand if this case is of little interest to you, Mr. Holmes, the missing articles being of no intrinsic value whatsoever’. That’s hardly as compelling as ‘Mr. Holmes, while the relics are of scant intrinsic value, from the historical point of view they are very nearly unique’. Your letter informing him of my refusal came like Manna from Heaven. He could show Sir Frederick he’d tried to bring in Europe’s most famous Consulting Detective. No-one would ever dream the larcenist was Lacey himself. He would be able to use the pilfered artefacts to ‘salt’ the field of his choosing.”

“Thereby,” I added, “becoming one of the most famous men in England.”

“Yes,” my companion nodded. “As famous in the archaeological world as Charles Dawson has become in the world of the palaeontologist and anatomist.”

Together we walked across the historic fields. A line of horse-drawn cabs was forming at the Abbey entrance, the fine arrangement of bays and cobs snorting into their nose-bags, ready for the day’s influx of visitors. We went to a Landau driven by a pair.

“Cabbie, the Tiger Inn,” Holmes instructed. “An extra guinea for you from the captain here if we arrive before their kitchen runs out of that well-armed sea creature, the lobster.”

1 This was a case published under the title Sherlock Holmes and the Sword of Osman (2015, MX Publishing).