Moviemaking is never as good as what you imagine. Any good idea that’s floating in the air—that’s the best.1

THE CHARACTER OF Spiderman was created by Marvel Comics editor Stan Lee in 1962 as a “modern” hero who would break the comic book formula by losing as many battles as he won. He was a more human superhero, riddled with angst, who would interact with the real world and experience self-doubt and failure. Similarly, Dr. Robert Bruce Banner, as the Hulk, is an antihero, a figure who in times of stress finds himself transformed into the dark (green) personification of his subconsciously repressed rage and anger. In the early 2000s, both Spiderman and the Hulk were the first of the Marvel superheroes to have internationally-acclaimed studio films made of their comic strip personas. Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man (2002) led to sequels in 2004 and 2007, and has been credited with reigniting the comic book genre and making “superhero-ism” fashionable again, leading to increasing forays into the comic book universe (more recently with the Iron Man franchise, the Avengers, and Captain America, etc.). Lee’s $150 million blockbuster Hulk (2003) was an early anticipator of this trend, coming just a year after Raimi’s film, and seemed set to capitalize on the new popularity of the superhero film.2 The ubiquitous presence of these comic book heroes in the media since they were created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in the early 1960s, including the Spiderman animated cartoon series (1967–1970) and The Incredible Hulk television series (1977–1982, with Bill Bixby and Lou Ferrigno), established them as international icons. (In 1978, a Spider-Man tokusatsu animated series was produced for Japanese television by Toei Company Ltd; apart from Spider-Man’s costume it was not based on the original source, but despite its differing storyline, this animation helped push Spiderman to the status of worldwide iconography.) And yet, what was the draw of the comic superhero Hulk for a filmmaker of the stature of Ang Lee, coming as he did off the success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon?

No doubt Lee was drawn to the subject because comics are treated as a serious art form in Asia; “man hua” or “comics” in Taiwan have a devoted following. Young people in Lee’s home country of Taiwan are thoroughly acquainted with the comic book medium—more so than young readers in America or Europe. Taiwanese young people are very involved with comic strips, comic books, and comic art in the form of cartoon images and characters. Beginning with “Hello Kitty” and “Snoopy,” most Taiwanese students from a young age are enamored with comic books and characters. As they grow into their teenage years, Taiwanese students spend a great deal of time poring over comic books produced in Taiwan and also “manga” imported from Japan—comics are an art form that they already have appreciated with considerable sophistication. Young Taiwanese also admire the heroic qualities of present-day cartoon icons such as Doraemon, Yu-Gi-Oh, or various Pokémon figures such as Pikachu, and these characters take on a profound and well-loved cultural significance. Students at the university level continue to enjoy renditions of ancient Chinese legends and elaborate martial arts series. In a related example, it can be observed that the popularity of animation from Asia has been taken more seriously in the West in recent years, particularly Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro (Tonari no Totoro, 1988), Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, 2001), which won the Best Animated Feature at the Academy Awards in 2002, and Howl’s Moving Castle (Hauru no Ugoku Shiro, 2004), which was nominated for Best Animated Feature in 2005.

The comic strip and comic book art forms are also very fresh and exciting media for exploration by a filmmaker. Joe Kubert (1999) dates the appearance of the first superheroes in comics to the mid-1930s.3 The unique nature of comic book and comic strip conventions can be explored on film: the vocabulary, the characters, the frame-by-frame narration, the humor, and speech versus thought bubbles, for example. The characters are generally static from week to week—a reader may become familiar with the characters and the nature of the comic strip, and then be fairly confident about what to expect in terms of characters, vocabulary, setting, style of humor, etc. Comic strips such as The Hulk or Spiderman also have their unchanging protagonists; in addition, these superhero comic strips are of a serial nature, telling a continuous narrative story from week to week. Spiderman and The Hulk have both also been serialized in comic books devoted to these characters alone. These characteristics of the medium build up loyalty and familiarity within the comic book subculture. In addition, these comic book heroes and their films provide the student with a simple narrative plot, the story of good versus evil played out by basic archetypes. There is much room for culturally relevant inquiry concerning “good guys” and “bad guys,” justice and redemption. Moreover, comic books and films are an offshoot of the fertile genre of science fiction, with its traditional laboratory elements such as experiments gone awry, Cold War sensibilities, suspicion of the government and secrecy of scientific inquiry, the introduction of nuclear power and radiation/mutation (in the case of the character of Spiderman, who is bitten by a radioactive spider, and the Hulk, who is injected with mutating cells touched off by a laboratory accident dealing with nuclear fusion). Finally, a third interesting feature of these comics/films is the wide range of cutting-edge language and modern English pop-art idioms; some examples included the comic book sound of a fist hitting someone’s face (“Pow!”), a shriek of terror (“Eek!”), or Doonesbury’s use of slang.

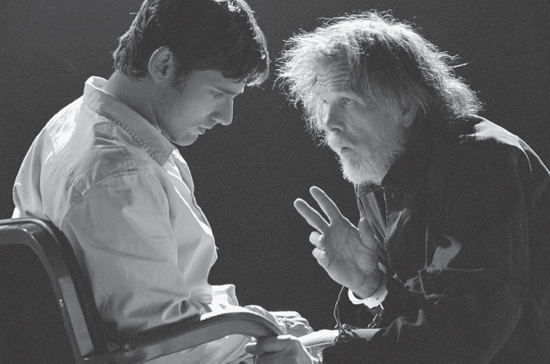

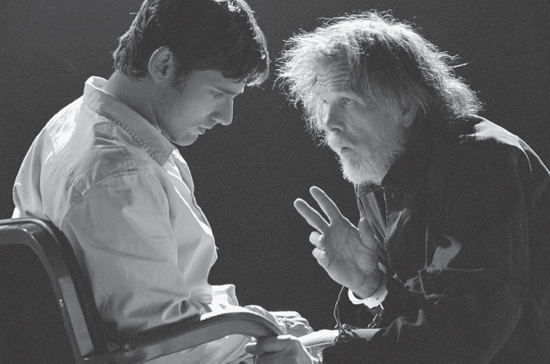

In a discussion on comic heroes, several topics may be explored in greater depth, such as the origins of comic heroes, the meaning behind comic narratives, or the filmmakers’ objectives in bringing their narratives to the screen. For example, Ang Lee’s motivation for making Hulk is a curious question. Why would a filmmaker thus far devoted to telling sentimental tales aim to make a summer blockbuster with a budget in the many millions of dollars? Had Lee finally “sold out,” shamelessly devoting himself to this ill-fitting format of megawatt advertising and market tie-ins? Was this—the superhero action genre—how Lee now sought to have his name imprinted in the consciousness of the international filmmaking world? In all probability, the film Hulk became larger and more unwieldy than the one Lee had originally set out to make. His trademark themes—of family and deep, personal character study—were no doubt foremost in his mind as he envisioned Hulk’s screenplay. The film retains much of the small-family focus. Intimate moments abound—between Bruce (Eric Bana) and his father (Nick Nolte), Bruce and Betty (Jennifer Connelly), Betty and Bruce’s father, Betty and her own father (Sam Elliott). Stripped of its over-the top, comic book antics, this film is a small family drama of the kind at which Lee excels. The scene in which Bruce and his father (in chains) face off on a large, brightly-lit stage is nearly Shakespearean in the force of its tragedy and drama. The set is even lit like a stage—with tortured soliloquies performed under spotlights. It is in scenes like this that the viewer is treated to Ang Lee’s true greatness of interpretation in the drama of the family.

In addition, the element of Hulk’s narrative which most likely attracted Lee’s interest is his dislocation from society—his alienation caused by his maniacal father. The Hulk longs to be normal—and to have a happy romance with his love, Betty—but he cannot fit in. He will never fit in. Betty tries to accept him, but she cannot. He is too strange, too different, doomed to walk through the world as an outsider. This theme of alienation, of being a cultural misfit, is a common theme in Lee’s work. His three earliest films—the Chinese trilogy consisting of Pushing Hands, The Wedding Banquet, and Eat Drink Man Woman—all deal with the dislocation between Western and Eastern cultures. The figure of the Hulk, who longs to be loved and accepted, embracing his girlfriend Betty tenderly after going on a wild, untamed rampage, is a pathetic one, as is the image of the Hulk plummeting forlornly back to earth after hanging onto the fuselage of an airplane. No one wants him—he is completely rejected by humanity. He is the ultimate antihero.

Perhaps Lee was facing an impossible task as he attempted to win the audience’s sympathy, understanding, or affection for the disenchanting Hulk. The Hulk, as he was first drawn in the early comic book series, is not a superhero but an antihero. His abnormal powers do not lead to glory and honor, but to alienation and isolation. Dr. Robert Bruce Banner is a Jekyll-and-Hyde figure who cannot control his anger. Instead of keeping his negative emotions inside, he becomes overwhelmed by them and is transformed into a hideous green monster acting out his repressed rage.4 The source of this rage, in Lee’s film, is his father’s accidental murder of his mother, but in modern psychological terms he demonstrates the externalization of his dysfunctional childhood; this is to gain sympathy for his character and his plight. Lee’s treatment of him reflects a sympathy with this unmanageable pain and anger. The film was a plaintive cry, asking the audience to show compassion for this terrible, flawed hero. But were the hearts of the audience soft enough to love this character?

Spiderman as a hero is a different story. The character is an “everyman” superhero, a very human superhero who experiences angst, self-doubt, and failure. Peter Parker is a scrawny nerd who faces inevitable mediocrity and unrequited love until a bite from a radioactive spider infuses him with supernatural powers. As Spiderman, he carries on a battle for justice—the triumph of the little guy—but at great personal sacrifice. Thus, Spiderman offers a more likeable and audience-friendly hero than the Hulk. Interestingly, both the Hulk (debut May 1962) and Spiderman (debut August 1962) were among Stan Lee’s most famous comic book creations, which also include The Fantastic Four (debut November 1961). The difference is that the audience cheers for Spiderman and pities the Hulk. Stan Lee outlines the formula for his superhero comics’ success in the introduction to a book on Marvel Comics: “The trick … is to create a fantastic premise and then envelope it with as much credibility as possible.”5 He explains how Spiderman endows a man with the supernatural abilities to spin webs and fly through the air, but then makes him as familiar and human as a next-door neighbor. “Despite his super powers, he still has money troubles, dandruff, domestic problems, allergy attacks, self-doubts, and unexpected defeats.”6 He also highlights Marvel’s strict requirements for natural-sounding dialogue between the characters, as well as the element of humor essential to even the most somber of stories.

In understanding Stan Lee’s achievement as the creator of the superheroes Spiderman and the Hulk, it is illuminating to review the literary origins that served as a source of inspiration to him. He had a considerable literary background and anticipated that he would only be in the comic business for a short time before going on to become a serious writer. In publishing his comic book creations, Lee changed his name from Stanley Martin Lieberman because “I felt someday I’d be writing the Great American Novel and I didn’t want to use my real name on these silly little comics.”7 Some of his literary influences include Edgar Rice Burroughs, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Robert Louis Stevenson, and he admired the sonority of Shakespeare and the Bible.8 His creation of the original Hulk series (The Incredible Hulk) was drawn from two distinct literary and cultural sources. Boris Karloff’s filmic portrayal of the monster in Frankenstein (1931) was an inspiration because, in the film narrative, the monster is “basically good at heart,” but he is “hunted and hounded” by society;9 these twin characteristics are shared by the Hulk. The second influence is Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—Lee was interested in a character that would transform from normal to monstrous and back again at random. In the Hulk, he sought to create a character with a tortured soul on the scale of Greek tragedy. His description of the Hulk is that of a character who would “never know a moment’s peace, never have the chance to have a normal life or dare to wed the girl he loved.”10 In summing up the complexity of his comic creations, Lee concludes, “We’re proud that Marvel was largely responsible for transforming comic books into a form of entertainment which today appeals to readers of all ages.”11 Stan Lee was given a positive sign that the comic book heroes he had created were having a social impact when a contingent of Columbia University students came to his office to announce the Hulk was their new mascot; Ivy League students could obviously sympathize with an intellect-driven scientist who was periodically pushed over the edge into an emotional rampage:

Marvel’s revolutionary style of storytelling was still in its embyonic stages, but already it was attracting an older and more sophisticated audience than comic books were conventionally expected to reach. … Despite condescending conventional wisdom, the imaginative world of comic books has always attracted the most intelligent kids: the introverted readers and dreamers who have fantasies of acquiring brawn to match their brains. And the Marvel heroes, with their sudden physical transformations and endless personal problems, spoke to the hopes and fears of troubled adolescents everywhere. Hordes of readers who had not looked at a comic book in years were suddenly being drawn back into the fold by Marvel’s new approach. … Marvel had fortuitously tapped into a demographic gold mine: the gigantic generation of baby boom children and teenagers who had been born in the years following World War Two. This group [was] one of the largest, best-educated and most affluent generations in American history.12

For the sophisticated Hulk reader, this film also affords its pleasures, in the form of subtle parallels with the original comic series. There are numerous self-referential plotlines that conjure up references to former Hulk stories. For example, when Betty first meets David Banner, they discuss a man named “Benny.” This is a reference to a soldier named Benny from the Hulk comics’ “Dogs of War” story arc, which introduced the concept of Hulk dogs used in this film. Another example is the scene in which General Ross heads toward San Francisco to intercept the Hulk, and his helicopter is codenamed “T-Bolt”; this is in homage to the nickname by which he is usually referred to in the Hulk comics, General “Thunderbolt” Ross, because of his short temper. In addition, the actor playing Ross in the film, Sam Elliott, had his doubts about wearing a mustache as the army does not encourage facial hair, but he agreed to Ang Lee’s wishes as General Ross sports a mustache in the comic books. Other corresponding details between the comics and the film include the following: David Banner works as a janitor in the film; this is a reference to the comic book character Samuel Sterns, a janitor who would eventually become the Hulk’s arch-enemy, “The Leader.” When Banner first bombards himself with gamma rays, the “mimic” powers he displays are a homage to “The Absorbing Man,” a villain from the Hulk comics. Finally, Banner’s transformation into the giant electrical being near the end of the movie is a homage to the classic Hulk villain “Zzzax.”13

Stylistic Features of the Hulk and Spider-Man

The success of comic book films like Hulk and Spider-Man was largely dependent upon the film technology of computer-generated imaging (CGI), a relatively new technology at the time. Creating the CGI Hulk was the most complex task ever undertaken by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to date; ILM employees logged over 2.5 million computer hours in the one-and-a-half years it took for Hulk to come to life. The computer model of the Hulk created by ILM used 12,996 texture maps and required 1,165 muscle movements. ILM designers studied human subjects performing the actions Hulk does in order to create his movements; initially they used bodybuilders but found them to be too cumbersome so eventually they settled on personal trainers. The amount of CGI involved in the scene where Hulk battles the three mutant dogs was one of the hardest, most complicated scenes ILM had ever done. Ultimately what ended up on screen was only a third of what was originally storyboarded; to have filmed the entire storyboarded version would have been simply too expensive. According to Ang Lee’s DVD commentary, the dogfight scene in the woods was originally envisioned with the Hulk fighting the monster dogs while naked. However, this was thought to be too difficult for a PG-13 movie, and so the Hulk does not appear naked until the very end of the fight. It was a deliberate decision to withhold showing Hulk in daylight until much later into the film, giving the audience the chance to get used to seeing him. When the first Hulk-out (transformation of Banner into Hulk) occurs, the color of the Hulk is either gray or greenish-gray; this is in homage to the original appearance of Hulk when he was actually gray in his first comic book appearance (Hulk #1, May 1962). From the second Hulk-out he maintains his prominent green hue. Moreover, there are three distinct Hulks in the movie; as Hulk gets angrier he gets bigger. The first (angry) Hulk is nine feet tall, the second (angrier) Hulk is 12 feet, and the third (angriest) Hulk is 15 feet tall. The Hulk had to move at a top speed of 300 miles per hour and be able to leap 3–4 miles in a single bound. According to ILM, the Hulk would be able to exert 14 tons of pressure per square inch and thus smash through almost anything in his path.

How successful, then, were the filmmakers (in the early days of CGI) at bringing these superheroes and their narratives to life? The original 2002 film Spider-Man greatly condensed the story of Peter Parker and his physical/psychological transformation, but still presented a stirring and complex story of one man’s struggle to do the right thing with the limited choices he is given. Spider-Man garnered critic accolades and high box office grosses. What of the Hulk? Touted as an even larger blockbuster than Spider-Man, and costing US$137 million to make, the Hulk achieved only moderate returns at the box office. A preview advertisement run several months in advance of the film’s opening seemed to draw only negative reactions from audiences, who criticized the film’s CGI graphics as being less sophisticated than Donkey Kong, a reference to the look of outdated video-game technology. A 2003 New Yorker article described the desperation of the studio in reaction to this news as Ang Lee himself climbed into the motion capture technology suit in an effort to improve the work of the graphic designers and give the Hulk a more realistic bearing.14 In a nuanced performance, Lee tried to capture with his own body and facial expressions the anger and agony of the character of the Hulk. Ultimately, due to the limits of the technology, however, the complexities of human emotion could not be captured effectively in a computer-generated image. Rather than depicting the sweaty, tearful, grief-stricken expression of a human being, the computer image seemed limited and puppet-like, without nuance or pathos. The computer-generated Hulk lacked the eyes and expressiveness of a real actor/person, so that the human element the audience needed to identify with the character was missing. Looking into a computer-generated character’s eyes, all the viewer sees is computer art; looking into a person’s eyes, the viewer sees into a soul, a life. While the audience was sometimes allowed to sympathize and identify with Hulk when he was in the form of Bruce Banner, more often the viewer was called upon to sympathize with Hulk as a CGI figure. Meanwhile, Spider-Man fared better, because when the audience was called to sympathize closely with the protagonist, he was not suited up as Spiderman but instead maintained intimacy as the real, human face of Peter Parker.

In some ways it can be argued, however, that the Hulk film is rendered more imaginatively and takes more daring risks. For example, the structure of the plot in Spider-Man is a straightforward hero-versus-nemesis theme, while Hulk explores family drama in several different directions: Bruce versus his own father, Bruce’s mother versus his father (in flashback), Betty versus her father, and finally, Betty versus Bruce. In addition, the presentation of the Hulk is unique in its use of comic book conventions from the written page. For example, in the opening of the film, the Green Marvel font of the main titles pays cultural homage to the original comic books. In addition, during certain action sequences Lee splits the screen into multiple comic book panels that dramatize the original comic strip format of the Hulk narrative. Moreover, Lee comments that the film has a complex philosophical subtext involving change and transformation embodied by lichen growing on rocks and mutation at a cellular and molecular level; images representing this idea occur throughout the movie. In preparation for filming Hulk, Lee studied “molecular growth, blood cells, galaxies, and [according to] Dennis Muren, ILM’s senior visual-effects supervisor, ‘how there’s some connection in the universe that makes everything work: a kind of yin-yang thing he wanted to get into the story.’ Lee also collected twenty-four boxes of rocks—‘their texture shows the flow of time, they remind you that the universe is kind of a big pot of soup,’—as well as lichen, starfish, and jellyfish, whose shapes were intended to help his collaborators imagine the Hulk’s dissonant interior.”15 There is no such imaginative subtext in Spider-Man.

The films’ taglines can be compared as well. “With great power, there must also come great responsibility” is the tagline in Spider-Man, a line spoken repeatedly by Peter’s uncle to remind him of his obligation to serve justice. This obligation comes at great personal sacrifice to Peter, who must give up his love interest, Mary Jane Watson, to serve society at large. This idea is noble and heroic in comparison to the Hulk’s tagline: “The inner beast will be released.” Other taglines used to advertise the film include: “Rage. Power. Freedom,” “On the 20th of June, let it all out,” and “Unleash the hero within.”16 These lines are evidence of the mixed message of the film; the release of rage is considered, on the one hand, heroic, and on the other, destructive. Even the taglines reflect that the makers of the Hulk weren’t entirely agreed on the message they wanted to promote, demonstrating a fundamental lack of unity in the film’s vision.17

The Challenge of Hulk

Ultimately, Ang Lee’s Hulk is about taking risks and attempting to transform the genre of hero-action movies in the same way the director has experimented with the conventions of “genre” in his past films. In stretching to create a unique vision, the filmmakers worked hard to bring a depth to the film that is surprising in its sophistication. John Lahr notes in the New Yorker interview that Ang Lee’s office walls revealed the esoteric inspirations for his cinematic imagery: “de Chirico for the colors and shapes of the Southwest, where part of the movie is set; Maxfield Parrish for sky tones, Rousseau and the Hudson River School Painters for the sense of scale; Picasso’s Dora for the montage of tension; and Cezanne for everything else. On the other side, interspersed with moody comic-strip panels, were the swirling patterns of William Morris and Jackson Pollock.”18 It is difficult to imagine that the makers of the Spiderman franchise put such lofty erudition into the filming of Spiderman and Spiderman 2.

The complexity of the Hulk plot mirrors this sophisticated thematic vision. The narrative is a challenging parable about modern science being a double-edged sword—both the threat of out-of-control experimentation and the promise of a better future. Marvel Comics heroes from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s historically reflected twentieth-century anxiety over the inexorable forward momentum of scientific discovery. Specifically, radiophobia, the fear of radiation and radioactive materials brought on by extensive atomic weapons’ testing and experimentation (in Hiroshima and Nagasaki), played a large role in the comic book narratives of this era.

The fear of radiation was a theme that recurred throughout the early 1960s, and again, radiation was the gimmick that provided the protagonist with his uncanny powers. Overt anxiety about the unleashed atom had diminished somewhat since the 1950s, even if only due to familiarity with the idea. However, a strong undercurrent of concern remained, and many of the superheroes of The Marvel Age owed their existence to the dreaded new technology. For Jack Kirby, the concept was more than just an easy way to set a story line in motion: “As long as we’re experimenting with radioactivity … there’s no telling what may happen, or how much our advancements may cost us.” The Hulk became Marvel’s most disturbing embodiment of the perils inherent in the atomic age.19

This inherent danger in radiation experiments is illustrated in the Hulk film, capturing the contradictory nature of these scientific advancements. Experiments in the film’s research facility are designed to help heal wounded animals by injection with gamma rays. However, in one scene, a bullfrog receives too much gamma radiation and literally explodes—a shocking and graphic demonstration of how wrong scientific experimentation can go.

These same complexities of theme run through the Hulk narrative. Berkeley scientist Bruce Banner does biomedical research, and struggles with his absence of memories from his early childhood. He has flashbacks and dreams which obliquely refer to a terrible early-childhood trauma. Bruce believes himself to be an orphan until his father David Banner appears as a janitor in the lab. David Banner is truly the “mad scientist” and villain of the story, whose tampering with biomedical research and experimentation with his own DNA has caused a genetic flaw to be passed on to his son. When Bruce’s genetic structure receives accidental exposure to strong radioactivity, it sets off a terrifying reaction which turns him into a gigantic, raging monster. Bruce’s on-again, off-again girlfriend, Betty Ross, struggles with her own past and her father, General Ross, in a way that parallels Bruce.

| Betty: |

How are you feeling? |

| Bruce: |

OK, I guess. |

| Betty: |

I think that somehow the anger you felt last night is triggering the nanomeds. |

| Bruce: |

How could it? We designed them to respond to physical damage. |

| Betty: |

Emotional damage can manifest physically. |

| Bruce: |

Like what? |

| Betty: |

A serious trauma … a suppressed memory. |

| Bruce: |

Your father grilled me about something I was supposed to remember from early childhood. |

| Betty: |

He did? |

| Bruce: |

Yeah. It sounded bad. But I honestly don’t remember. |

| Betty: |

What worries me is that a physical wound is finite, but with emotions, what’s to stop it from going on and on, and starting a chain reaction? |

| Bruce: |

Maybe next time, it’ll just keep going. You know what scares me the most though? When it happens, when it comes over me—when I totally lose control—I like it.20 |

Bruce’s past haunts him in dreams, but his memory has been cauterized by the terror he experienced as a child. Thus, his memory is repressed—he is unaware of the terrible childhood memories that afflict his psyche. The discussion relates physical damage with emotional damage, referring to the common idea in psychoanalysis that subconscious emotions and memories can have physical manifestations, and that the doer may not be aware of these subconscious motivations. This dialogue displays the key statement: “You know what scares me the most though? When it happens, when it comes over me—when I totally lose control—I like it.” This line from Bruce Banner underscores how the dark and mysterious forces inside the human heart can be pleasurable to express. It explores the question of whether or not humans should control their animal instincts, and to what degree the expression of this rage and anger is acceptable, normal, or healthy. Lines such as the following suggest that expressing uncontrollable anger is bestial, or something other than human:

| Betty: |

How long are you gonna keep Bruce sedated? |

| Ross: |

The rest of his natural life, if I have to. |

| Betty: |

You said I could trust you. |

| Ross: |

I’m your father. You can trust me to do what I think is right, not what you think you want. |

| Betty: |

He’s a human being. |

| Ross: |

He’s also something else.21 |

This is a conversation between Betty and her father General Ross. Betty and her father also have issues—he has wanted to capture Bruce as a weapon to be used by the U.S. government. Rather than viewing him as the inhuman result of a scientific experiment gone awry, Betty expresses a desire to protect and nurture him—she is torn between her fear of his raging, uncontrollable anger and her loyalty to the Bruce she has known as a tender human being. Betty says to her father:

| Betty: |

Look, I know the government thinks they have a weapon on their hands or he’d be dead already. They can probe and prod all they want, but in the meanwhile, you have to let me help him. Nobody knows him better than I do.22 |

In the above dialogue from the screenplay, Betty reveals her fierce loyalty to the Bruce Banner she knew as an intimate friend, and the memories of their shared past (“Nobody knows him better than I do”). Betty refuses to give in to the pressure to view Bruce Banner as something different, something inhuman.

David Banner’s motives are mixed, perhaps reflecting his mental instability as he slowly becomes more and more deranged. At first, his actions seem to simply reflect the conventional Greek-tragedy storyline of the sins of the fathers visited on their own sons. At certain moments, he actually seems regretful and contrite toward his son. However, he has other darker motives for reestablishing contact with Bruce. Throughout the film, but especially toward the ending, David Banner’s major desire is for achieving an infinitely powerful state of existence in which he will be able to become immortal by cheating death. To do so, he must harness his son’s power. It is a classic father/son conflict: the father loves his son, but his love becomes clouded by his lust for power.

| Father: |

And what did I do to [my son], Miss Ross? Nothing! I tried to overcome the limits in myself—myself, not him. Can you understand? To improve on nature, my nature. Knowledge of oneself, that is the only path to the truth that gives men the power to defy God’s boundaries.23 |

This aspiration for absolute power is set in contrast with the Oedipal notion that men must kill their fathers if they want to grow up:

| (David Banner walks toward his son, reaches out with his manacled hands.) |

| Bruce: |

No. Please don’t touch me. Maybe, once, you were my father. But you’re not now—you never will be. |

| Father: |

(Beat.) Is that so? Well, I have news for you. I didn’t come here to see you. I came for my son. |

| |

(Bruce looks up at him, confused.) |

| Father: |

(Cont’d.) My real son—the one inside of you. You are merely a superficial shell, a husk of flimsy consciousness, surrounding him, ready to be torn off at a moment’s notice. |

| Bruce: |

Think whatever you like. I don’t care. Just go now. |

| |

(The Father smiles, laughs.) |

| Father: |

But Bruce—I have found a cure—for me. (beat—now more menacing) You see, my cells too can transform—absorb enormous amounts of energy, but unlike you, they’re unstable. Bruce, I need your strength. I gave you life, now you must give it back to me—only a million times more radiant, more powerful. |

| Bruce: |

Stop. |

| Father: |

Think of it—all those men out there, in their uniforms, barking and swallowing orders, inflicting their petty rule over the globe, think of all the harm they’ve done, to you, to me—and know we can make them and their flags and anthems and governments disappear in a flash. You—in me. |

| Bruce: |

I’d rather die. |

| Father: |

And indeed you shall. And be reborn a hero of the kind that walked the earth long before the pale religions of civilization infected humanity’s soul.24 |

The final climactic battle between father and son is ambiguous, and this confusion has led many critics to condemn the film. This dramatic confrontation can be understood in various ways. As James Schamus has explained the complexity of the drama in the New Yorker: “The Hulk sacrifices himself to defeat his enemy, which is, in the person of his father, really himself.”25 A deleted scene from the DVD has Bruce the scientist offering the following explanation:

Ang Lee’s interest in the father-son conflict is brought into high relief as Bruce Banner clashes with his mad-scientist father.

| Bruce: |

Life is both the ability to retrieve and to act on memory … Part of life is death, is forgetting, and unchecked, it’s mutateous, it’s monstrous … Basically to stay in balance and alive we must forget as much as we remember. |

The intensity of the repressed memories has caused Bruce severe emotional damage. However, in the end, he may have been able to forget or to give out his memory/power and transfer it/relinquish it to his father (who is given the powers of Absorbing Man, an obscure Marvel villain). Special effects render the father’s astounding mutation into a humongous, tortured, and bloated creature. In the end, the father has absorbed too much of his son; the power is out of control. “Take it back!” he screams, “It’s not stopping—TAKE IT BACK!” This is the chilling ending to the classic conflict.

The last moments of the film show us that Bruce Banner has not only survived the battle, but is using his skills as a physician in South America. His alter ego the Hulk has survived as well, ready to smash evil and defend innocent people. The last line of the film comes when Bruce, confronting a soldier, says in Spanish: “You’re making me angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.” This is a reference to the line made famous in the pilot and opening sequence of The Incredible Hulk (1977). It also leaves the plot open-ended, to set up a possible sequel. The line about “anger” displays one of the central questions in the story: how to control, or alternately, how to express, anger. The film deals with how sorrow, anger, and all the other related emotions can build up within a man and can manifest physically. The anger caused by the familial conflict within Hulk, as the father and son wrestle over the son’s power and potential, is of course reminiscent of the troubled relationship Ang Lee had with his own father as he yearned to break free of parental control to pursue his artistic vision. “I gave you life,” the father David Banner tells his son, implying obligation and service to the creator’s will. In reality, Lee never dared to respond to his own father’s pressure with the type of anger Bruce displays in Hulk; however, one can ascertain in this film a certain subconscious Oedipal aggression.

In another complicated plot twist the fathers (Banner and Ross) are enemies because of some terrible event in the past involving Banner setting off a radioactive bomb that turns the army base into a wasteland—General Ross bans him permanently from the U.S. army. Ross makes reference to this:

| Betty: |

I want you to help him! Why isn’t that simple? Why is he such a threat to you? |

| Ross: |

Because I know what he comes from! He’s his father’s son, every last molecule of him. He says he doesn’t know his father—he’s working in the exact same goddamn field his father did. So either he’s lying, or it’s far worse than that, and he’s … |

| Betty: |

What? Predestined? To follow in his father’s footsteps? |

| Ross: |

I was gonna say “damned.”26 |

Thus, the Greek tragic theory of the sons being punished by the sins of the fathers comes full circle—Betty as well is under a curse from her family lineage. The Hulk is both an intricate psychological drama with a modern-day Achilles as a hero, and a love story of doomed lovers who can never have a happy ending to their love story (in this way, it prefigures the themes of Brokeback Mountain). The question is, can the audience sympathize with the Hulk’s predicament; to take Betty Ross’s position, is it possible to accept the Hulk as he is, fatally flawed? Critical response to the film showed that the audience did not have its sympathy won over by the sensitive portrait of the antihero. The thinking man’s action movie about Man’s inner demons did not hold broad appeal. While some critics praised Lee’s daring departure from the conventional treatment of the comic book drama, the film was pummeled by most viewers who criticized the effort to turn Hulk into Hamlet with art-house visual effects. According to the IMDb website, while the film’s first weekend gross was $62,128,420, its second weekend gross was $18,847,620, a mere 30 percent of the first weekend. Hulk holds the record for largest second weekend box office drop for a film that opened at number one, with a –69.7 percent drop.

Historically, Bruce Banner became one of the first comic book protagonists to hate his constant transformation into a superhero. What comes through most clearly in the Hulk film is that Banner himself has conflicting views of his own abilities, and that he knows he presents a real danger to himself and others. The threat of this danger provides a tension throughout the film. Aware that his destructive emotions lead to unpleasant consequences, the Hulk must necessarily become antisocial: “Have to get away—to hide.”27 This condition makes him a sympathetic menace. The Hulk is cursed with a weakness of character (which he battles with the strength of his will) who throughout the film is trying in vain to hold his rage in check and not be transformed into the alter ego he despises—a brutish, out-of-control monster. Thus Hulk is not a story of anger, destruction, and hatred, but a parable about triumph of the will, courage, and hope. It is this compelling, hope-against-all-hope desire to see Bruce learn to control his rampaging emotions that provides the dramatic tension of the narrative.

While the Hulk was not the best comic book film, and not the most successful of Ang Lee’s movies, the shadow of what Lee is looking for appears in the film—the continued desire to invite the outsider in, to render acceptable what is unacceptable. This is what Lee calls the “juice” of the film, “The thing that moves people, the thing that is untranslatable by words.”28 It is this underlying theme of longing for a kind of redemption—for acceptance—that Hulk shares with all of Lee’s films.