Poor Relief, Charity,

and Self-Help in

Crisis Times, 1834–69

The adoption of the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834 marked the end of an era of generous public assistance. In the four decades before the act’s passage, the Poor Law played the largest role of its 350-year history, assisting the unemployed and underemployed as well as widows, children, the sick, the elderly, and the disabled. Relief expenditures as a share of gross domestic product, real per capita expenditures, and the percentage of the population receiving relief were higher from 1795 to 1834 than at any other time before the twentieth century. The share of relief recipients who were prime-aged males also peaked between 1795 and 1834, and was especially high in the grain-producing South and East, where a large share of relief spending consisted of payments to seasonally unemployed agricultural workers or weekly allowances for poor laborers with large families. For most recipients, poor relief took the form of cash or in-kind payments to the poor in their homes.1

The generous nature of the Old Poor Law sparked a wave of criticism from political economists and other commentators. Critics opposed granting outdoor relief to able-bodied males on the grounds that it reduced work incentives and thrift among the working class. Frederic Eden, author of The State of the Poor (1797), maintained that public assistance “checks that emulative spirit of exertion, which the want of the necessities … gives birth to: for it assures a man, that, whether he may have been indolent, improvident, prodigal, or vicious, he shall never suffer want.” Thomas Malthus, the most influential participant in the pre-1834 debate, argued that the Poor Laws, by guaranteeing assistance to those in need, “diminish both the power and the will to save among the common people, and thus … weaken one of the strongest incentives to sobriety and industry, and consequently to happiness.”2

Widespread clamor for reform led the government in 1832 to appoint the Royal Commission to Investigate the Poor Laws. The commission’s 1834 report called for the grouping of parishes into Poor Law unions and the appointment of a centralized Poor Law Commission to direct the administration of relief. The report focused largely on the granting of outdoor relief to able-bodied males, concluding that it tended to “diminish, we might almost say to destroy, all … qualities in the labourer.” It recommended that relief be granted to able-bodied adults and their families only in well-regulated workhouses, and confidently predicted that the use of workhouses would restore the industry and “frugal habits” of the poor, and improve their “moral and social condition.”3

Critics of the Old Poor Law believed that the substitution of workhouses for outdoor relief would lead workers to protect themselves against income loss by saving more and joining friendly societies. The number of able-bodied male applicants for relief would greatly decline, and the Poor Law’s main job would be to assist widows and orphans, the non-able-bodied, and the elderly. The New Poor Law would usher in an era of financially independent workers and lower taxes.

The relief system initiated in 1834 was subjected to a major test within a decade of its creation by the downturns of the hungry 1840s, and to additional tests in the 1860s by the Lancashire cotton famine and the Poor Law crisis in London. These shocks revealed serious flaws in the new system. While the New Poor Law led to increased savings by working-class households, the amount that the typical household was able to save was small, and any spell of unemployment lasting more than a few weeks exhausted most workers’ savings. Second, the Poor Law was not set up to deal with the sharp increases in need that occurred during business-cycle downturns. The downturns of the 1840s led to widespread unemployment, and many of the unemployed, once their savings were depleted, were forced to apply for poor relief. Both the working class and local relief officials believed that the cyclically unemployed, who lost their jobs through no fault of their own, should be eligible for outdoor relief. Moreover, the number of able-bodied relief applicants far exceeded the available workhouse space. Poor Law unions in manufacturing districts found it physically impossible and morally unacceptable to relieve the cyclically unemployed and their families in workhouses. Finally, the system of taxation used to fund the Poor Law proved unable to raise enough money to assist all those in need. These flaws led to the rise of short-term charitable movements to fill the gap between the demand for relief and its supply during both the 1840s and 1860s.

This chapter explores the roles of the Poor Law, private charity, and self-help in urban areas during the hungry 1840s, the Lancashire cotton famine of 1862–65, and the London crisis of the 1860s. I set the stage with a brief summary of the effects of the Poor Law Amendment Act on public relief and on the rise of working-class self-help.

I. The Decline in Relief Spending

and the Rise of Self-Help

Soon after the Royal Commission’s report was published in 1834 Parliament adopted the Poor Law Amendment Act, which implemented some of the report’s recommendations and left others, like the regulation of outdoor relief, to the newly appointed Poor Law Commissioners. By 1839 the vast majority of rural parishes had been grouped into Poor Law unions, and most unions in southern and eastern England either had constructed or were constructing workhouses. By contrast, the commission met with strong opposition when it attempted in 1837 to set up unions in the industrial North, and the implementation of the New Poor Law in several industrial cities was delayed.4

The change in the administration of relief led to a sharp fall in poor relief expenditures. From 1812 to 1832, relief expenditures for England and Wales as a whole averaged 1.9% of GDP, peaking at 2.2% during the post-Waterloo downturn of 1816–20. For 1835–50, relief spending averaged only 1.1% of GDP, peaking at 1.3% during the downturns of 1842 and 1848.5

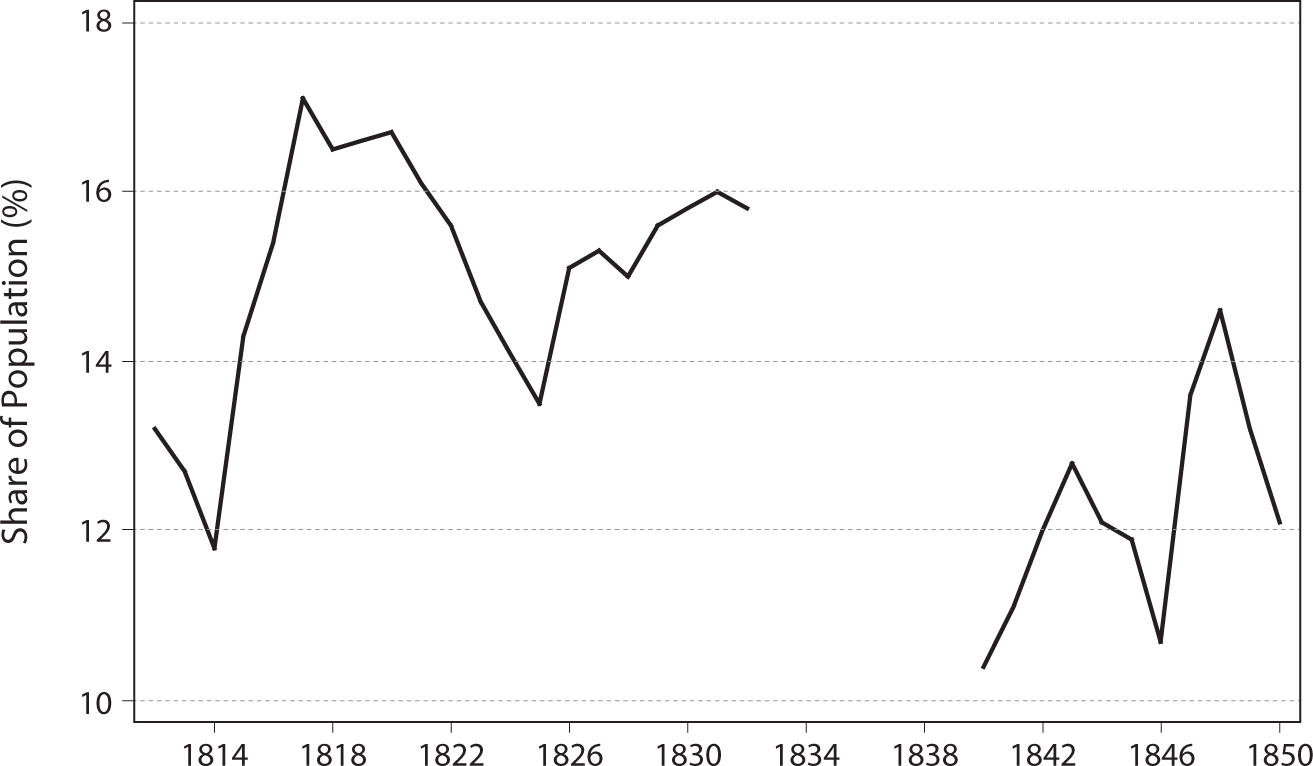

Data on the number of poor relief recipients in the first four decades of the nineteenth century are available only for 1802–3 and for 1812–13 to 1814–15. However, it is possible to use these data, along with annual expenditure data, to construct rough estimates of the number of relief recipients in the years leading up to the Poor Law Amendment Act. These new estimates of the share of the population receiving poor relief for the years 1812–32 are presented in Figure 2.1, along with estimates for 1840–50. The construction of the estimates is explained in Appendix 2.1. It must be stressed that these estimates are rough and are meant to yield only a general idea of the extent of the decline in numbers on relief after 1834. That said, Figure 2.1 shows that on average 15.1% of the population was in receipt of relief in the two decades leading up to the Poor Law Amendment Act. The peak occurred in 1817–20, when the share relieved averaged 16.7%. In 1830–32, on the eve of the appointment of the Royal Poor Law Commission, nearly 16% of the population received public assistance. The size of the “pauper host” declined after 1834. During the “hungry 1840s,” an average of 12.2% of the population received poor relief at some point in a year. The share receiving relief averaged 10.4% in the 1850s, and continued to decline thereafter.

FIGURE 2.1. Share of Population Receiving Poor Relief, 1812–50

The magnitude of the decline in relief spending varied across regions, being largest in rural southern England, where Poor Law unions were first organized and workhouse construction began (see Table 2.1). From 1834 to 1837, per capita relief expenditures declined by 48% in the South and 42% in the East, as compared to 32% in the industrial North West and 27% in the North. The sharp downward trajectory in spending lasted only three years. In all regions per capita expenditures were higher during the hungry 1840s than in 1837. In the North West, per capita relief spending during the downturns of 1841–43 and 1847–48 was higher than it had been the year before the Poor Law Amendment Act was adopted, suggesting that the Poor Law’s role in industrial cities was not altered substantially by the act.

The group most affected by the New Poor Law was adult able-bodied males and their families, in particular those in the rural South and East where the new system initially was enforced. Outside of this region, the Poor Law Commission and its 1847 replacement, the Poor Law Board, issued several orders to selected Poor Law unions in an attempt to regulate the granting of relief to able-bodied males. The Outdoor Labour Test Order of 1842, sent to unions without workhouses or where the workhouse test was deemed unenforceable, stated that able-bodied males could be given outdoor relief only if they were set to work by the union. The Outdoor Relief Prohibitory Order of 1844 prohibited outdoor relief for both able-bodied males and females except on account of sickness or “sudden and urgent necessity,” and the Outdoor Relief Regulation Order of 1852 extended the labor test for those relieved outside of workhouses. However, as will be made clear in the next section, these orders were evaded by urban Poor Law unions throughout England, especially during cyclical downturns. Urban workers viewed the right to outdoor relief when unemployed as part of an “unwritten social contract” with employers, and most local relief administrators in manufacturing cities agreed.6

TABLE 2.1. Regional Poor Relief Expenditures, 1834–52 |

|||||||

|

PER CAPITA POOR RELIEF EXPENDITURES (SHILLINGS) |

||||||

Region |

1834 |

1837 |

1840 |

1843 |

1846 |

1848 |

1852 |

London |

8.3 |

4.9 |

5.3 |

6.2 |

5.8 |

6.9 |

5.4 |

South |

13.6 |

7.2 |

7.8 |

8.3 |

7.8 |

9.0 |

6.9 |

East |

15.2 |

8.8 |

9.2 |

9.1 |

9.2 |

10.4 |

8.1 |

South West |

9.1 |

6.2 |

7.5 |

7.7 |

7.2 |

8.9 |

6.7 |

Midlands |

7.8 |

4.9 |

5.1 |

5.8 |

5.2 |

6.3 |

4.8 |

North West |

4.3 |

2.9 |

3.4 |

4.9 |

3.6 |

5.5 |

3.6 |

North |

6.8 |

5.0 |

5.1 |

5.5 |

4.9 |

5.4 |

4.6 |

|

PER CAPITA POOR RELIEF EXPENDITURES (RATIO) |

||||||

Region |

1834 |

1837 |

1840 |

1843 |

1846 |

1848 |

1852 |

London |

100.0 |

59.2 |

64.0 |

74.9 |

70.1 |

83.1 |

65.2 |

South |

100.0 |

52.3 |

57.0 |

60.5 |

56.5 |

66.2 |

50.3 |

East |

100.0 |

57.8 |

60.8 |

60.2 |

60.8 |

68.8 |

53.2 |

South West |

100.0 |

68.7 |

82.0 |

84.4 |

79.6 |

97.9 |

74.3 |

Midlands |

100.0 |

63.4 |

65.9 |

74.2 |

67.2 |

81.1 |

61.5 |

North West |

100.0 |

67.9 |

79.3 |

113.1 |

84.1 |

127.4 |

83.4 |

North |

100.0 |

73.0 |

75.5 |

81.0 |

72.3 |

79.4 |

67.3 |

Source: Constructed by author from poor relief expenditure data in the Annual Reports of the Poor Law Commission and the Poor Law Board. |

|||||||

Working-class self-help was relatively small before 1834, largely because of the low level of wage rates, but perhaps also because of the generous nature of poor relief. Pre-1834 data exist for two forms of working-class thrift—membership in mutual insurance organizations known as friendly societies and deposits in savings banks. Returns from local Poor Law overseers indicated that in 1815 there were 925,400 members of friendly societies in England, representing 29% of males aged 15 and over. All of these societies were local organizations, and some were little more than burial clubs. Many were financially unstable and provided only “short-term benefits.”7 Probably no more than 50–60% of members were in societies that paid sickness benefits.

The share of the population belonging to friendly societies in 1815 varied substantially across regions. It was largest in Lancashire and other northern and Midlands industrial counties, where one-third to one-half of males 15 and older were members of societies, and lowest in southern and eastern rural counties, where fewer than one-in-five adult males were members. A House of Lords Select Committee reported county-level estimates for 1821 of friendly society membership as a share of total population. The ranking of counties is similar to that in 1815—the incidence of membership was highest in Lancashire (17%) followed by Staffordshire (14%), and lowest in Sussex (2.5%).8 Membership was highest in counties where per capita poor relief spending was low, and lowest in counties where per capita spending was high. There are several possible but conflicting explanations for this finding. Perhaps, because wages were higher in the North and Midlands than in the South, northern workers had “surplus earnings” to devote to mutual insurance. Another explanation, put forward by many contemporaries, was that the generosity of the Poor Law in the rural South and East reduced insecurity for working-class households by enough that most found it unnecessary to purchase mutual insurance.9 Proponents of this explanation maintained that restricting outdoor relief would lead southern workers to join friendly societies even if their wage rates did not increase.

Membership in local societies stagnated from 1815 to the early 1830s. However, this same period witnessed the rise of the national affiliated orders. The largest of these, the Independent Order of Oddfellows, Manchester Unity (IOOMU), was founded in Manchester in 1810 and by 1831 claimed to have 31,000 members. The Ancient Order of Foresters (AOF) was founded in Leeds in 1813 and claimed 16,510 members in 1835.10 Adding together local societies and affiliated orders, membership in friendly societies in the early 1830s probably totaled slightly less than a million. Perhaps 600,000 members (16% of adult males) were in societies paying sickness benefits.

Parliament established the Trustee Savings Banks in 1817 in an attempt to encourage working-class saving. These banks had about 425,000 depositors in 1830, with deposits totaling £14.6 million (see Table 2.2). In order to determine the extent of working-class saving, it is necessary to separate deposits of manual workers from those of the middle class. Few if any workers had deposits greater than £50, and many deposits under £50 “belonged to children of prosperous parents.”11 In 1830, 79% of depositors had balances less than £50, and 51% had balances less than £20. The upper limit of the number of working-class depositors therefore was 340,000; the actual number probably was about 280,000. Depositors with balances less than £50 held 38% of the £14.6 million in deposits in 1830, or £5.5 million. Total working-class deposits almost certainly were less than this; a rough estimate suggests that workers’ balances totaled £3.2 million, or 22% of deposits.12 This represented about 57% of spending on indoor and outdoor poor relief in 1830.13 In sum, before 1834 only a small minority of working-class households either belonged to friendly societies offering sickness benefits or had deposits in a savings bank.

THE EFFECT OF POOR LAW REFORM ON SELF-HELP

The relative importance of self-help and public relief began to change after 1834. The Poor Law Commission did not eliminate outdoor relief to the able-bodied, but it succeeded in restricting relief for able-bodied males and in reducing relief expenditures.14 At the same time, there was a sharp increase in friendly society membership and private saving. Membership in the Manchester Unity Oddfellows increased from 31,000 in 1832 to 90,000 in 1838 and 259,000 in 1846, while membership in the Foresters increased from 16,500 in 1835 to nearly 77,000 in 1846. Of the 3,074 English lodges of the IOOMU in 1875, 1,470 (48%) were established between 1835 and 1845, more than three times as many as were founded in any other decade. Other, but smaller affiliated orders also were established during these years, including the Independent Order of Rechabites and the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds, who between them had 32,000 members in 1846.15 Table 2.2 shows that membership in the four affiliated orders, taken together, increased from under 50,000 in 1830 to nearly 370,000 in 1846, before declining to about 329,000 in 1850. There are no data on the membership of local societies in the 1830s and 1840s, but it probably increased as well, albeit more slowly than the affiliated orders. I estimate that total friendly society membership in 1850 was roughly 2 million, about 40% of adult males (Table 2.2).16 Membership in societies paying sickness benefits probably was between 1.2 and 1.35 million.17 Thus, from 1830 to 1850, the share of adult males insured against income loss due to sickness increased from roughly 16% to 25–29%.

Private saving also increased greatly after 1834, as shown in Table 2.2. The number of working-class depositors grew from about 280,000 in the early 1830s to 750,000 in 1850, at which time between one-fifth and one-quarter of adult working-class males had a savings bank account.18 It should be stressed, however, that even with the impressive growth in private saving and friendly society membership, before 1850 the majority of working-class households neither had a savings account nor belonged to a friendly society paying sickness benefits.

What caused the increase in self-help after 1834? It was not caused by a sharp increase in wage income; from 1830–32 to 1844–46, manual workers’ real earnings increased on average by only 10%.19 The Assistant Poor Law Commissioners for the rural South East reported examples of wages and employment increasing as a result of the abolition of outdoor relief for able-bodied males, but these increases were not large enough to explain the change in workers’ behavior.

The Poor Law Commission attributed much of the growth in friendly society membership and working-class saving to the reform of the Poor Law. Assistant Poor Law Commissioners reported in 1835 that “medical clubs are starting up in all directions” in districts where the New Poor Law had been implemented.20 One wrote in 1842 that Kent and Sussex had witnessed a “vast increase” in friendly society members and a substantial increase in deposits in savings banks since 1834.21 Tidd Pratt, the barrister appointed to certify the rules of savings banks and friendly societies, reported in 1838 that there had been a sharp increase in the number of benefit-society lodges since the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act, and that from November 1833 to November 1836 the amount of money deposited in savings banks by individuals had increased by 22%. Pratt stated that the founders of new lodges wrote to him that “now is the time that parties must look to themselves, as they could not receive out-door relief under the new law.” He attributed the increasing number of depositors in savings banks to the reform of the Poor Law.22

In sum, while the effect of the New Poor Law on working-class self-help cannot be determined precisely, it seems probable that some part of the increase in friendly society membership and savings bank deposits after 1834 represented a working-class response to the declining availability of outdoor relief, and that working-class households, on average, devoted a larger share of their income to self-help in the 1840s than they did before 1834. It is important not to misinterpret this conclusion. It should not be viewed as support for the Royal Poor Law Commission’s assertion that large numbers of workers abused the Poor Law before 1834. Workers sought to minimize their economic insecurity, and they responded to the shrinking public sector safety net by protecting themselves against income loss.

II. Poor Relief, Charity, and Self-Help

during the Hungry 1840s

THE FUNDING OF POOR RELIEF

The Poor Law was administered at the local level. Before 1865, each parish within a Poor Law union was responsible for relieving its own poor, within the legal and fiscal constraints imposed from above. Poor relief was financed by a property tax, known as the poor rate, assessed on “land, houses, and buildings of every description” within the parish, but not on firms’ profits or stock in trade. Machinery typically was not taken into account in estimating the rateable value of factory buildings.23 Under this system of assessment, a large share of the poor rate was levied on occupiers of dwelling houses. An 1842 report concerning Stockport classified all assessments of £8 or less as working-class dwellings, and assessments of £8–20 as dwellings of foremen, clerks, small shopkeepers, and “persons of small independent means.” Assessments of more than £20 included the “higher classes of private residences,” large shopkeepers, and publicans, as well as factories.24 In 1848–49 the majority of collected poor-rate assessments in each of three Lancashire cities—Ashton-under-Lyne, Manchester, and Preston—were valued at less than £8, and more than 80% were valued at less than £20. I estimate that assessments on working-class dwellings contributed 14–28% of the poor rate in these cities, and that all assessments valued at less than £20 contributed 32–45% of the poor rate.25

The assessment system had important implications regarding who paid for poor relief. Ratepayers in industrial cities can be divided into three groups—manufacturers and other major employers of labor, working-class households, and the remaining ratepayers (merchants, shopkeepers, landlords, tradesmen, etc.). If manufacturers in Ashton-under-Lyne, Manchester, and Preston paid between one-half and two-thirds of the rate collected from assessments of £20 or more, then they contributed 27–46% of the poor rate, “a distinctly modest contribution to local expenditure.”26 Because rates were levied on occupiers of dwelling houses rather than owners, workers, most of whom rented their tenements, paid part of the tax, though poor workers often were excused from paying “on account of poverty.” Moreover, some of the tax levied on occupiers would have been shifted to their landlords.27 Non-labor-hiring middle-class taxpayers paid a quarter or more of the poor rate. The more successful working-class occupiers were in shifting the rates on dwelling houses to their landlords, the larger the share of the poor rate paid by middle-class taxpayers.28

The Poor Law generally was capable of handling relief costs. However, during the “hungry” 1840s it proved unable to meet the increased demand for assistance in many cities, due to both the high number of unemployed workers and the decline in the effective tax base resulting from sharp increases in the default rate of taxpayers. The problem faced by parishes during downturns can be seen from some basic accounting. A parish’s supply of poor-relief funds at a point in time t can be written as rt(1 −d)tVt, where r is the poor (tax) rate, d is the share of the tax bill that was not paid (the default rate), and V is the total value of rateable property in the parish. Relief expenditures at time t are equal to gtstPt, where g is the generosity of relief per recipient, s is the share of the local population being granted relief, and P is the population of the parish. Setting tax revenue equal to relief expenditures yields the equation rt(1 −d)tVt = gtstPt. Rearranging terms, the poor rate at time t is determined as rt = gt stPt/(1 −d)tVt. In recession years, the share of the population granted relief increased, the parish’s value of rateable property often declined, and the default rate increased. In order to assist everyone who applied for relief, parishes were forced to increase the poor rate, reduce the generosity of relief, or deny relief to some who should have qualified for it. Increases in the poor rate tended to cause further increases in the default rate, so that there was a maximum beyond which parishes refused to raise rates. The inability of the Poor Law to meet the increased demand for relief during downturns was made clear within a decade of the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act, when the sharp increase in relief spending in 1841–42 caused a financial crisis for Lancashire Poor Law unions and forced many to cut benefits and appeal to private charities for help in assisting the needy.

DISTRESS IN THE MANUFACTURING DISTRICTS

DURING THE HUNGRY 1840S

After the boom of 1835–36, the economy slumped badly in 1837. There was a weak recovery in 1838–39, followed by the severe depression of 1841–42. The recovery that began in 1843 culminated in the prosperous years 1845–46, but another serious downturn followed in 1847–48. The downturns of 1841–42 and 1847–48 were particularly severe in the Lancashire cotton industry. Profit rates were low from 1837 to 1840, largely because of overinvestment in plant and equipment, and when demand declined in 1841–42 firms had few reserves and many went bankrupt and stopped production. In 1847 the cotton industry experienced a shortage and high price of raw cotton as a result of poor harvests in the United States in 1845 and 1846. At the same time, domestic demand for cotton goods declined, possibly due to declining real wages caused by rising food prices.29

The unemployment data for the cotton industry in Manchester and surrounding towns in 1841–42 are not complete and historians do not agree on how to interpret the existing data. Leonard Horner, the inspector of factories, reported data on employment in 1,164 cotton mills in the fall of 1841, and found an unemployment rate at the time of inspection of about 15%. An additional 14% of factory workers were employed for a reduced number of hours per week. Horner admitted that because the information was collected over a 15-week period, the figures did not “strictly apply to … any one day for the whole district,” and Huberman contends that the reported data substantially understate the importance of short-time employment.30

The bottom of the downturn occurred in the spring of 1842. In his April report, Horner wrote that wage reductions of 10–12.5% were “becoming very general” and that short time probably was increasing. Three months later, he reported that “the great and general depression of trade continues unabated…. Many mills have stopped, many are working only four days in the week, and several only three days. This working short time, together with the reduction of wages, which has been very general, must press very severely upon the workpeople.”31 On July 9, 1842, the Manchester Times wrote that “any man passing through the district and observing the condition of the people, will at once perceive the deep and ravaging distress that prevails…. The picture which the manufacturing districts now present is absolutely frightful.” The economy was just beginning to recover when a young Friedrich Engels arrived in Manchester for the first time in November 1842. He later wrote that “there were crowds of unemployed working men at every street corner, and many mills were still standing idle.”32

Detailed studies of the magnitude of employment loss in 1841–42 are available for the cotton manufacturing towns of Bolton and Stockport. A director of Manchester’s Chamber of Commerce estimated that in the spring of 1842 some 62% of Bolton’s cotton workers were either unemployed or working short time, and that the extent of lost income for all Bolton workers resulting from unemployment, short time, and wage cuts was nearly £3,900 per week. Two Assistant Poor Law Commissioners sent in January 1842 to enquire into the state of the population in Stockport reported that “a considerable number of [cotton] mills” had completely stopped production, that many of the mills in operation had gone to short time, and that the wages of those employed had been reduced by 10% to 30%. They estimated that the loss of income for workers in the town’s cotton mills amounted to £5,483 per week.33

Unemployment rates in Manchester area mills were as high or higher in 1847–48. Data collected by the Manchester police and reported in theEconomist indicate that during the week ending November 16, 1847, near the trough of the downturn, 19 of 91 cotton mills had stopped production and another 34 were working short time. Fewer than half of the area’s cotton operatives were working full-time—some 26% were unemployed, and an additional 26% were working reduced hours. Conditions improved somewhat from December to February. Nevertheless, during the second quarter of 1848, 18.3% of the workforce in Manchester area cotton mills was unemployed, while another 13.6% was working short time.34

SELF-HELP, POOR RELIEF, AND PRIVATE CHARITY

Working-class households suffered substantial income shocks during the downturns in 1841–42 and 1847–48. The initial response of most households to employment loss was to reduce spending, withdraw money from savings accounts, and pawn unnecessary items. However, this was a short-term strategy for all but the most highly paid manual workers, as few had the resources to subsist for more than one or two months before applying to the Poor Law or organized charities for assistance.

The ability to save varied greatly across households, being determined by the household head’s wage, family size, and the number of household members working. It was difficult for any but highly paid manual workers to accumulate more than a few pounds in savings.35 Anderson concluded that “few even in good times could afford to save anything very significant to meet temporary losses in income … so that even short or comparatively minor crises caused severe destitution.” The unemployed often turned to locally residing relatives for help, although the amount of aid they could expect from kin was “definitely limited,” especially during serious downturns. Some moved in with relatives or neighbors in order to save money on rent and fuel.36 Many households pawned furniture, clothing, bedding, and other items, but the amount of money (loans) obtained from pawnbrokers typically was quite small, and the rates of interest charged were often 20–25% per annum. Still, for many low-skilled workers the pawnshop was “their one financial recourse…. In times of sudden and overwhelming distress there is no doubt of its utility.”37

Once savings were exhausted, workers turned to the Poor Law or charity. For most workers, the lag between becoming unemployed and applying for poor relief was short. Boot found that in Manchester during the 1847–48 downturn “the average lag between becoming unemployed and receiving [poor] relief” was about six weeks. Many low-skilled workers did not have the resources to hold out for six weeks, while some highly paid skilled artisans might have held out for much longer.38

Despite attempts by the Poor Law Commissioners to abolish its use, Poor Law unions in industrial areas continued to provide outdoor relief to unemployed and underemployed factory workers. As Rose stated, “the workhouse test was largely irrelevant to the problems of cyclical unemployment.” When the Poor Law Commission issued the Outdoor Labour Test Order of 1842, stating that able-bodied males could be given outdoor relief only if they were set to task work, urban Boards of Guardians objected, arguing that “it was degrading for those unemployed through no fault of their own to be set to work with idle and dissolute paupers.” Guardians in several unions also provided small payments to those whose hours of work were reduced during downturns.39

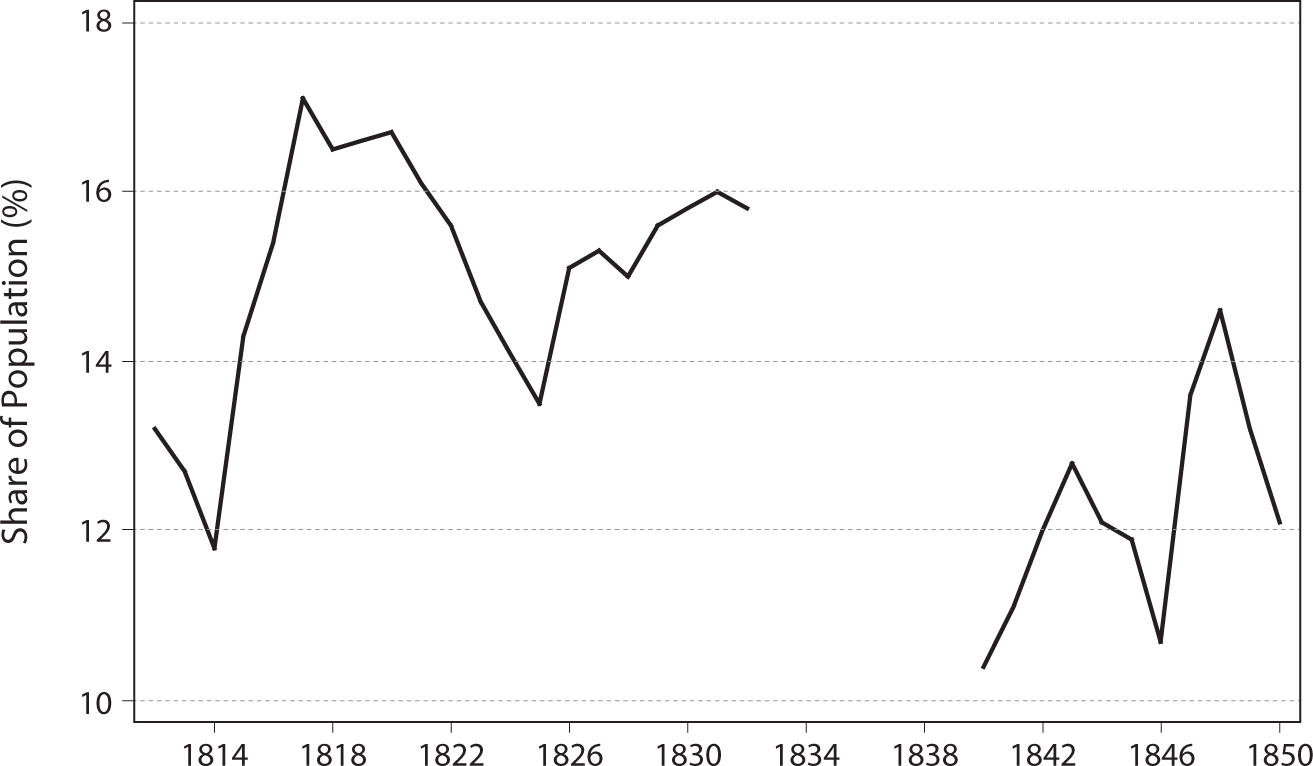

FIGURE 2.2. Per Capita Poor Relief Expenditures, 1840–52

The share of the population of England and Wales receiving poor relief exceeded 10% throughout the decade, peaking at 14.6% in 1848 (Figure 2.1). The cyclical nature of relief spending is more pronounced at the city level. Figure 2.2 shows per capita relief spending for fiscal years (ending March 25) 1840–52 in three northern industrial cities: Manchester and Preston, which specialized in cotton textiles, and Sheffield, which specialized in steel production. Spending increased sharply in each city in 1841–42 and 1847–48. Table 2.3 shows the number of persons receiving poor relief during the “quarters ended Lady-Day” (March 25) in 1841–43 for 12 urban industrial Poor Law unions, and the number receiving relief in the “six months ended Lady-Day” in 1846–48 for eight urban unions. The number relieved increased substantially during both downturns. In Stockport it doubled from 1841 to 1842 and more than quadrupled from 1846 to 1848, while in Manchester it increased by 58% from 1841 to 1843 and more than tripled from 1846 to 1848.

Increases in relief spending during downturns created serious financial problems for industrial cities. The size of the poor rate levied each year by a Poor Law union was determined by the expected demand for relief. When demand increased unexpectedly unions often were forced to levy two or more assessments per year. Stockport’s relief spending increased from £1,331 for the fourth quarter of 1838 to £2,329 for the same quarter in 1840 and £3,537 for the quarter in 1841.40 Table 2.4 gives the particulars of each of Stockport’s poor-rate assessments from October 1836 to June 1841. There were three assessments in 1841 totaling 4s. in the pound.41 The 2s. assessment in November was necessary because the number of relief recipients increased by 63% from June to December 1841. Default rates increased sharply during the downturn. In October 1836, a time of prosperity, 92% of the assessed poor rate was actually collected. However, as a result of the large number of defaulters, only 63% of the rates levied in February and June 1841 were collected. When Stockport collected its poor rate in November 1841, it was found that 1,632 of 6,180 working-class dwelling houses were unoccupied, as were 85 shops and 11 public houses. In addition, the occupiers of nearly 3,000 other dwelling houses did not pay the poor rate; upon examining 1,950 of the defaulters, the guardians excused 58% of them on the grounds of poverty. Most seriously, 12 of the town’s 40 factories had shut down, and could not pay their assessment.42 Under the circumstances, local officials surmised that another increase in the poor rate would cause more ratepayers to default and would yield little additional tax revenue.

TABLE 2.3. Numbers in Receipt of Relief in Industrial Cities, 1841–48 |

|||||

(A) 1841–43 |

POPULATION |

PAUPERS RELIEVED QUARTER ENDING MARCH 25 |

% INCREASE |

||

|

1841 |

1841 |

1842 |

1843 |

1843/1841 |

Blackburn |

75,091 |

5,057 |

8,604 |

10,307 |

103.8 |

Bolton |

97,519 |

8,016 |

10,378 |

11,934 |

48.9 |

Bradford |

132,164 |

7,340 |

9,514 |

9,572 |

30.4 |

Halifax |

109,175 |

7,436 |

8,992 |

9,474 |

27.4 |

Huddersfield |

107,140 |

6,880 |

9,431 |

13,092 |

90.3 |

Liverpool |

223,054 |

15,045 |

20,652 |

22,727 |

51.1 |

Manchester |

192,408 |

12,978 |

15,994 |

20,449 |

57.6 |

Preston |

77,189 |

8,672 |

13,237 |

11,822 |

36.3 |

Sheffield |

85,076 |

6,113 |

6,555 |

15,402 |

52.0 |

Stockport |

85,672 |

3,918 |

8,153 |

6,895 |

76.0 |

Leicester |

50,932 |

5,306 |

7,057 |

8,293 |

56.3 |

Nottingham |

53,080 |

4,589 |

7,938 |

5,751 |

25.3 |

(B) 1846–48 |

|

PAUPERS RELIEVED HALF YEAR ENDING MARCH 25 |

% INCREASE |

||

|

|

1846 |

1847 |

1848 |

1848/1846 |

Bolton |

|

9,033 |

15,527 |

16,004 |

77.2 |

Bradford |

|

20,070 |

24,055 |

39,759 |

98.1 |

Halifax |

|

13,758 |

19,512 |

17,950 |

30.5 |

Liverpool |

|

15,887 |

24,597 |

27,982 |

76.1 |

Manchester |

|

27,503 |

50,737 |

94,702 |

244.3 |

Stockport |

|

5,512 |

11,699 |

25,563 |

363.8 |

Leicester |

|

6,431 |

11,792 |

19,642 |

205.4 |

Nottingham |

|

5,581 |

8,648 |

9,232 |

65.4 |

Sources: Data for 1841–43 from Parl. Papers, Return of Average Annual Expenditure of Parishes in Each Union in England and Wales (1844, XL), pp. 5, 13, 17, 25. Data for 1846–48 from Parl. Papers, Return of the Comparative Expenditure for Relief of the Poor … in the Six Months Ending Lady-Day in 1846, 1847 and 1848 (1847–48, LIII), p. 1. |

|||||

Boards of guardians tried to set the generosity of relief benefits at a level high enough to ensure that unemployed or underemployed workers and their families were able to subsist in good health, but low enough so as not to interfere with work incentives. Benefit levels were remarkably similar across towns; guardians typically granted 2–3s. per week to a single adult male, and 1s. 6d.–2s. 6d. per week for each additional family member. Benefits were smaller if the applicant was working short time or if the family had other sources of income. In 1841 Bolton guardians granted applicants enough relief to make up their income “to 2s. 3d. per head per week… where we clearly ascertain the amount [the family] earned.”43

When downturns became severe, as in 1841–42, lack of funds often forced guardians to reduce relief generosity and to give relief in kind rather than cash. After the stoppage of several mills in August 1841 the Stockport guardians shifted to relieving the able-bodied entirely in kind. Bacon and butter were included in the provisions dispersed in August and September, but thereafter relief was entirely made up of bread, meal, and potatoes. Those in need also were provided with clothes, bedding, and clogs. The unemployed and local shopkeepers objected to the shift, but the guardians maintained that in-kind relief reduced the cost of relieving the unemployed by 20%.44

The relief distributed by the guardians did not come close to making up the income loss of Stockport’s mill workers. During the fourth quarter of 1841, spending on poor relief totaled £3,537, which was less than the estimated income loss of mill workers in one week (£5,483). The Assistant Poor Law Commissioners reporting on the state of the Stockport union defended the guardians’ actions, stating that “the certain exhaustion of the relief-fund at no distant period… [justified] the guardians in dispensing with the utmost care and economy the funds now supplied by a greatly-reduced number of rate-payers, whose number and whose resources are still continually on the decrease.”45

The inability of the Poor Law to support all who needed assistance led to large-scale charitable efforts to relieve the poor. In Manchester in 1841–42, local charitable organizations set up soup kitchens and provided the poor with bedding, clothing, and coal. More than 8,000 families were supplied with articles of bedding, and at the peak of the depression soup was supplied daily to 2–3,000 persons.46

In Stockport in October 1841, a committee composed of the mayor, clergymen, magistrates, and “leading manufacturers” was appointed to “inquire into the state of the poor and unemployed… and to suggest means for their relief.” The committee reported in December that while the poor rate had doubled, “it is impossible to collect sufficient [funds] to meet the current expenditure, and as small as the relief afforded is,… it is more than the resources of the rate-payers, if unaided, will continue to afford.” It appealed to the public for donations, and in December 1841 and January 1842 the committee raised nearly £3,000 from private contributions. From the last week of December through the end of February, it relieved on average 3,350 families at a cost of £340 per week. By comparison, during the two-year period from Lady Day 1841 to Lady Day 1843, the Stockport union spent £40,670 on poor relief, or about £390 per week. Most of the money raised by the Stockport relief committee was donated by “the wealthier inhabitants of the borough and those resident in the neighbourhood.”47

Stockport’s need to appeal for private charity to assist the unemployed reveals the inadequate nature of the poor-rate assessment system, which did not effectively tap the new wealth created by industrialization. The three poor rates levied in 1841 were both inadequate to relieve the large number of unemployed workers and at the same time large enough to be “a serious drain upon the diminished resources of the comparatively few [individuals and firms] who are able to pay them.”48 Rather than levy another poor rate, which would have resulted in even more defaults, Stockport set up a relief committee to raise funds privately. A large share of the charitable contributions must have been made by mill owners and merchants, two groups whose wealth was relatively lightly taxed under the assessment system. This was an inefficient way to tap the resources of the industrial elite; cities had no authority to compel manufacturers or merchants to make large contributions to the relief funds. Yet cities were forced to proceed in this manner because of the nature of the poor rate.

Not all charitable relief was raised locally. In its 1841 report, the Stockport relief committee stated that because of the great amount of distress among the unemployed, it was “fully convinced that all the efforts that can possibly be made in the town and neighbourhood will be utterly inadequate to meet the pressing necessities of the case.” It therefore appealed for assistance “to those individuals and classes of society who feel little of the pressure of the times.”49 In response to similar appeals from several cities, the Home Secretary instituted the London Manufacturers’ Relief Committee in the spring of 1842 “to co-ordinate and regulate the distribution to the provinces of charitable funds raised in England… to relieve industrial distress.” The committee contained 60 members, including the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. It received slightly more than £100,000 in donations. Three-quarters of the funds raised were in response to a letter from Queen Victoria read in English churches, appealing for aid for the unemployed. The rest was raised by subscription. By far the largest individual contribution came from Rev. J.H. Fisk, who made “the magnificent donation of £1,000.” Queen Victoria contributed £500, Prince Albert £200, and the Queen Dowager £300. The Bank of England and the Corporation of the City of London each contributed £500. Contributions of £200 or more were received from three London livery companies, three insurance companies, and eight individuals, including Prime Minister Peel.50

The committee granted relief to localities requesting it, provided they had already organized a local committee consisting of “magistrates, clergy and principal inhabitants,” and that local subscriptions had been raised for relief of the poor. It required that the major part of the relief be granted to able-bodied men and their families, that at least one-half of the relief be given in kind, and that work be required from able-bodied men in return for relief.51 From May 1842 until April 1843 the committee made a total of 734 grants—some cities received several grants. The recipients of the largest grants were Stockport, which received £8,100, Burnley, which received £12,300, and Paisley, which received over £15,000. More than 80% of the money distributed by the committee went to towns in Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cheshire, and Scotland.52

Paisley’s large grant was a result of the severity of its depression and the fact that under the Scottish Poor Law able-bodied males were not eligible for poor relief even when unemployed. At the beginning of the depression Paisley formed a General Relief Committee to raise money for the unemployed and their families. When the local fund proved insufficient, subscriptions were started in the county of Renfrew, in Edinburgh and Glasgow, and in London, where merchants connected with Paisley contributed to relieve the unemployed. Together, these funds raised £28,233 from June 1841 to May 1842. From December 1841 to May 1842, the committee assisted an average of 12,188 persons per week, or 20% of the population. Given the severity of the depression—a large share of Paisley’s businesses and merchants had gone bankrupt—the local community was unable to contribute more to the relief fund, and in spring 1842 the committee asked Parliament for help. From May 1842 to February 1843, 79% of the money spent to assist the Paisley unemployed was contributed by the London committee.53

The extent of charitable assistance for the unemployed during the 1847–48 downturn is more difficult to measure. Manchester charities raised approximately £19,000 in 1848 from subscriptions, donations, and collections, but it is not clear how much of this money went to aid the unemployed. In Leeds the unemployed were assisted by the Benevolent or Strangers’ Friend Society and by an ad hoc relief fund. The role played by private charity in 1847–49 was much smaller than it had been in 1842—the relief funds collected in 1847 and 1849 combined totaled £3,500, half of the amount collected in 1842.54

In sum, during the two major downturns of the 1840s the unemployed and their families were assisted by a combination of public and private sources. The Poor Law proved incapable of relieving the unemployed, so local voluntary organizations mobilized to help meet the increased demand for assistance. When this proved inadequate, localities appealed to Parliament for help. The government did nothing to fix the defects of the poor-rate assessment system, and the problems associated with the Poor Law came to a head in Lancashire in 1862.

III. Poor Relief and Charity during the Lancashire Cotton Famine

There were no severe economic downturns during the 1850s. The 1858 recession was shorter than either of the 1840s downturns, and is barely perceptible in the Poor Law statistics. The relatively low unemployment of the 1850s ended, at least in the industrial North West, shortly after the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861, when the Union blockade of southern ports led to the so-called Lancashire cotton famine. Raw cotton imports declined sharply, forcing Lancashire cotton factories to severely curtail production or shut down.

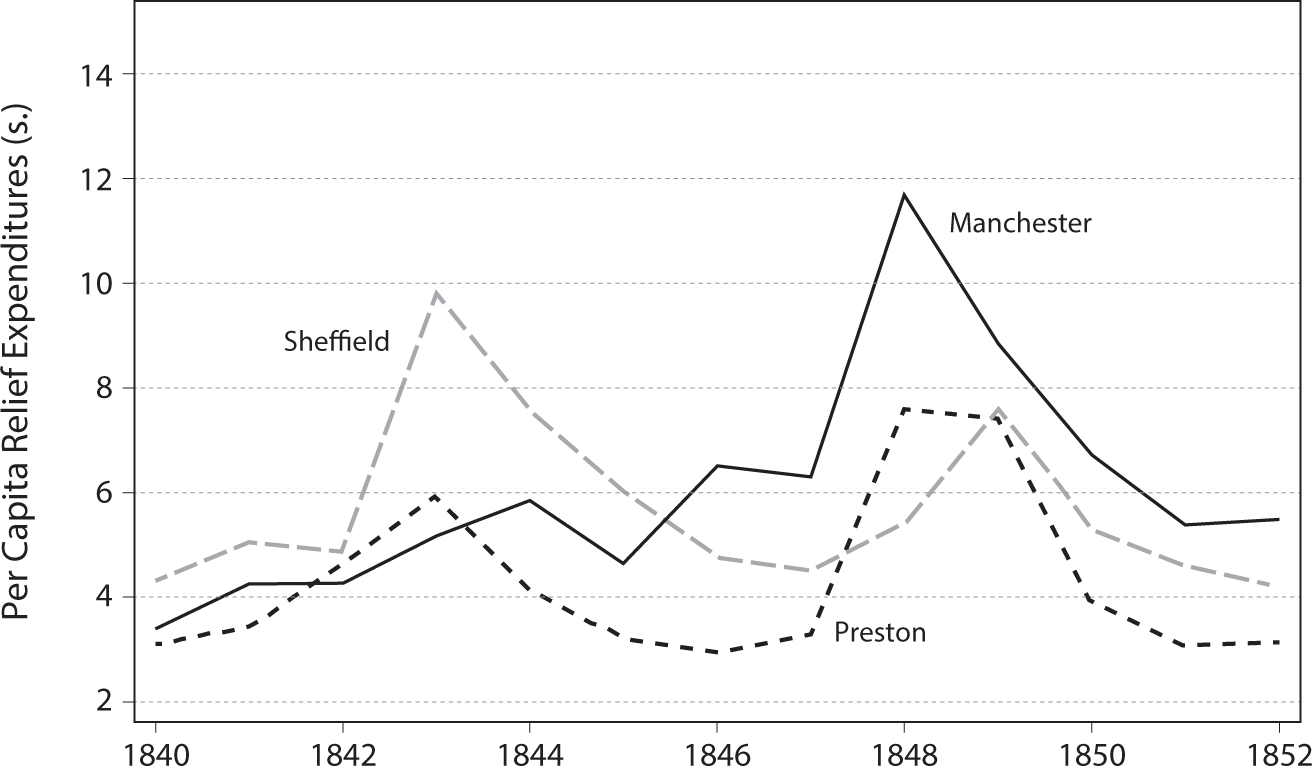

FIGURE 2.3. Number of Relief Recipients in 23 Lancashire Poor Law Unions, 1861–63

Weekly consumption of raw cotton began to decline in the fall of 1861, plummeting to 38% of its prefamine level in the last six weeks of the year. After rebounding in the first half of 1862 to two-thirds of its prefamine level, it fell sharply in the summer of 1862. In September consumption declined even further, to its lowest point during the famine. From August 29 to October 16 average weekly consumption was less than average daily consumption during the previous boom. Consumption increased slightly in late October and November, but remained less than a third of its prefamine level.55

Figure 2.3 shows the number of persons receiving poor relief in 23 “distressed” unions and townships in Lancashire and Cheshire for each week from November 1861 through February 1863.56 From the beginning of November 1861 to the third week in February 1862, the number receiving relief increased by 78%, from 47,039 to 83,550. The growth in numbers relieved then slowed considerably until early July, after which it increased at a rapid and accelerating pace until December. At the peak of the famine, in December 1862, there were 266,500 persons in receipt of poor relief in the 23 unions, out of a population of 1,870,600.

The extent of distress varied substantially across Poor Law unions, as a result of differences “in their dependence on the cotton industry [and] on the supply of American cotton,” and in the types of cotton cloth produced.57 Table 2.5 shows the percentage of the population receiving poor relief at six points of time for 11 large distressed unions and townships. From September 1861 to February 1862 the number of persons in receipt of poor relief more than tripled in Blackburn, Preston, and Stockport, increased by 162% in Ashton-under-Lyne, but rose by only 64% in Salford and 37% in Bolton. By June numbers on relief were five times greater than in the previous September in Ashton, four times greater in Blackburn and Stockport, and 3.75 times greater in Preston, and the relief roles continued to grow throughout the summer and fall. In September more than 10% of the population was receiving relief in five towns, and in November over 20% of the population was in receipt of public relief in four towns. An additional 200,000–236,000 persons were receiving relief from charitable funds at the peak of the famine. In total, 25–27% of the population of the distressed region was assisted by either public or private sources; in several Poor Law unions more than a third of the population must have received some form of assistance at the peak of the famine. Some of those receiving poor relief were assisted from charitable funds at the same time; the total number of persons receiving charitable relief in the winter of 1862–63 was almost certainly over 300,000, and might have exceeded 350,000.58

Most contemporaries agreed that demand for poor relief during the cotton famine was unprecedented. Arnold wrote that “the incidence of the poor-rate was never so oppressive over an equal extent of the kingdom as in the cotton districts during the months which included the crisis of the famine.”59 As had occurred in 1842, the increased demand for relief and the large number of defaults on poor-rate assessments caused Poor Law unions to run into serious financial problems. Wigan, Blackburn, Rochdale, Preston, and Ashton formed private relief committees early in 1862, and most of the other towns in the distressed area soon followed suit. By May 1862 the Blackburn committee had collected £5,234, the Preston committee £7,500, and the Rochdale committee £3,300. In order to induce wealthy individuals to contribute generously to the local relief committees, newspapers published the names of donors each week, often “listing the names in decreasing order of amount given.”60

In the spring of 1862 Lancashire officials began appealing to the rest of Britain for help. In April a group of London merchants associated with the cotton industry convinced the Lord Mayor of London to form the Lancashire and Cheshire Operatives Relief Fund (or Mansion House Fund). From May 1862 to June 1865, the fund contributed £528,336 to the distressed cotton districts. Another relief fund, the Bridgewater Fund, emerged in London, eventually raising £52,000 for the relief of Lancashire.61 Soon after the initiation of the Mansion House Fund the (Manchester) Central Relief Committee was formally established; it included the mayors and ex-mayors of the principal towns of the cotton district and a number of gentlemen associated with the commercial interests of Manchester. One of its first acts was the drafting of a resolution directed at city and county officials throughout Britain, requesting aid for families of distressed workers connected with the cotton trade. The money raised by the London relief committees went to either the Central Relief Committee in Manchester or the individual local committees to distribute.62

The total amount expended by public and private sources for relief of the Lancashire poor from March 1861 to March 1864 was about £3,530,400. Poor-relief expenditures equaled £1,937,900, or 55% of the total; charity accounted for the remaining 45%. Of the charitable funds raised, £786,400 (22%) came from the cotton districts; the remaining £806,000 came from elsewhere in Britain or overseas. Altogether, slightly more than three-quarters of expenditures came from local sources.63

There was some friction between authorities in the cotton districts and the London relief committees, as well as between the central executive committee in Manchester and the local boards of guardians and relief committees. The administrators of the London committees, anxious that the funds they raised should “relieve the destitute and not the ratepayers,” complained that local boards of guardians were not spending enough on poor relief. The guardians replied that there had already been an “oppressive increase in the rates,” and that any attempt to further raise rates “would have the effect of pauperizing those who are now solvent, and to augment rather than diminish the distress of the district.”64 Before making a grant to a local relief committee, the central executive committee required information about the locality’s expenditures on poor relief, the amount of charitable funds collected by the local committee, the number of unemployed operatives in the town, the number relieved by the guardians and the local committee, and the generosity of public and private relief. In this way the central committee was able to monitor the actions of the local committees.65

It also was suggested by many, in Lancashire and elsewhere, that wealthy cotton manufacturers were not contributing their fair share to the relief funds. The manufacturers replied that the famine had caused them serious financial difficulties, but that even so, they contributed to relieve the destitute in several ways. Some continued to run their factories even when it was not profitable for them to do so. Others “gave their ‘hands’ daily meals and established soup kitchens,” and those manufacturers who owned the cottages in which their workers lived generally did not collect rent during the famine.66 If manufacturers and other large employers paid 40% of the poor rate, and contributed half of the charitable funds raised within the distressed area, they would have paid one-third of the amount spent on public and private relief during the famine. Counting the value of rents excused and meals given to workers, manufacturers paid, at most, 40% of the cost of relieving the unemployed.

In the summer of 1862, when the resources of both the local boards of guardians and the relief committees began to be strained, Parliament intervened to ease the financial burdens of the distressed areas. The Union Relief Aid Act, adopted in August 1862, had three major provisions. First, if the poor rate of any parish in the distressed area exceeded 3s. in the pound, the excess should be charged to the other parishes in the Poor Law union. Second, if the aggregate rate for a union exceeded 3s. in the pound, it could apply to the Poor Law Board to borrow the excess, to be repaid within seven years. Third, if the aggregate poor rate for a union exceeded 5s. in the pound, the Poor Law Board could order other unions in the county to contribute money to meet the excess. The first provision effectively shifted part of the cost of relieving the unemployed from working-class parishes to wealthier parishes in the same Poor Law unions. The extent of this cost shift was quite large in some unions. For the half year ended Lady Day 1863, 82.9% of relief expenditures in Ashton-under-Lyne were charged to the union common fund, and only 17.1% to the individual parishes. In Stockport, Rochdale, Preston, and Blackburn, two-thirds or more of relief expenditures were charged to the union. The major beneficiaries of the second and third provisions appear to have been Ashton-under-Lyne and Preston—from August 1862 to July 1864 Ashton borrowed £31,300 and received £7,000 from other Lancashire unions, while Preston borrowed £28,900 and received £10,800 from other unions.67

In July 1863 Parliament adopted the Public Works (Manufacturing Districts) Act, which allowed local boards of guardians to borrow money from the national government for 30 years at an interest rate of 3.5%. The money was to be used for public works projects using the labor of unemployed cotton operatives, who were to be hired to do unskilled manual labor and paid the going wage for unskilled workers. From 1863 to 1865, 90 local authorities borrowed £1.85 million to construct public works. Although many beneficial projects were undertaken, the act was a failure as an employment project. Rather than create so many as 30,000 jobs for unemployed operatives, as its sponsors expected, peak employment on public works was 6,424 in October 1864; only 4,990 of those employed were cotton operatives.68

During the cotton famine, officials who typically tried to maintain relief benefits at about 2s. per person per week were forced to reduce benefits to less than 1s. 6d. per person. Guardians realized that the relief they were granting was inadequate and “assumed that this meagre sum would be augmented from other sources.” Their assumption appears to have been correct. A January 1863 estimate suggests that over 60% of individuals receiving outdoor relief from the guardians also received assistance from the local committees.69 In combination, poor relief and private charity were able to maintain the generosity of relief at about its prefamine level. George Buchanan reported at the peak of distress in 1862 that “taking the great mass of the cotton workers with their families as a whole, their average income… from all sources is nearly 2s. per head per week. This is exclusive of clothing, bedding and firing which are now usually supplied in addition.”70

Modern studies of relief generosity often focus on the relationship between benefits and wages. During the cotton famine, the central executive committee in Manchester strove to maintain an average benefit/wage ratio of about one-third. However, because an unemployed individual’s benefits were tied to the size of his family rather than his wage, the benefit/wage ratio varied across relief recipients. If unemployed cotton operatives received 2s. per family member per week in public and private relief, an unemployed class 3 spinner from a family of four would have had a replacement rate of 37% in 1862–63; for a class 1 spinner the replacement rate was 20%.71

IV. The Crisis of the 1860s in London

The Lancashire cotton famine was not the only Poor Law crisis of the 1860s. During the decade “the English poor relief system was subjected to an almost continual series of shocks which exposed its basic weakness.”72 London was especially hard hit. By the 1850s the metropolis contained 30 separate Poor Law unions, each responsible for its own poor. Population shifting within London led to increasing divergences in financial resources across unions. Middle-class taxpayers moved from central London to outlying districts, while the working class became ever more concentrated in certain unions, especially in the East End. As a result, districts where the demand for poor relief tended to be high were also those where the tax base was low.73

The extent to which poor rates varied across London Poor Law unions is shown in Table 2.6, which presents information on rateable value and poor rates for 12 unions in the 1860s. Rateable value per capita, a rough measure of wealth, varied substantially across unions, exceeding £7 in St. George Hanover Square, Paddington, and Kensington, and being less than £2.5 in the East End unions of Shoreditch and Bethnal Green. As discussed in Section II, a union’s poor rate in any year was determined both by the value of its rateable property and by the demand for relief. In 1860 the poor rate varied from 0.35s. in the pound in Paddington to 2.71s. in the pound in St. George in the East—taxpayers in the East End paid rates more than four times higher those of taxpayers in the wealthier West End.74

The Thames froze in the winter of 1860–61, causing a decline in all outdoor work and the complete cessation of riverside employment for several weeks. The resulting flood of applications for relief created severe problems in East London Poor Law unions. During five weeks of severe frost in December and January, the number of relief recipients increased by nearly 40%.75 As in northern industrial cities, the increased demand for assistance led to a large increase in private charitable expenditures. One witness testifying before the Select Committee on Poor Law Relief, appointed to examine the distress in London in 1860–61, estimated that between £28,000 and £40,000 was raised by various charities to assist the poor.76 Much of this money was distributed at the local Police Courts. The magistrates in charge of distributing relief “had no knowledge ourselves whether [applicants] were in distress or not,” and admitted that, due to the large number applying for assistance, money was distributed quickly and rather indiscriminately. The Select Committee concluded that “a large proportion of the charitable funds was wasted upon undeserving objects.”77

Witnesses appearing before the committee disagreed as to whether Poor Law unions could have met the demand for assistance without the help of charitable relief. The chairman of the Shoreditch Board of Guardians testified that he was “certain” that the guardians could have relieved all persons in his district who needed assistance, including those who turned instead to charity. On the other hand, Rev. McGill of St. George in the East testified that “it was too much to ask the local guardians of a distressed district like St. George’s-in-the-East, or like Bethnal Green… [to relieve] the distress which existed during those five weeks of frost.” The assistant overseer of St. George Southwark testified that the increased demand for relief made it increasingly difficult to collect the poor rate, and that each quarter between 1,200 and 1,500 persons had to be summoned before the magistrates because they did not pay their rate.78 The committee concluded that “the Guardians could have raised the funds which would have been required, if the relief of the whole of the distress had been cast upon them, but it must be borne in mind that the chief portion of the destitution was confined to those districts of the Metropolis which are always most heavily burthened with the poor…. It is obvious, therefore, that the additional charge upon the pauperized parishes would have sensibly increased the difficulties of the ratepayers.”79

The London Poor Law suffered an even larger shock from 1866 to 1869, when the combination of a business-cycle downturn, the decline of the London shipbuilding industry, and severe winter weather greatly increased the demand for poor relief. Once again, the East End was hardest hit.80 Panel (a) of Table 2.7 shows the number of persons in receipt of poor relief in the last week of the Christmas quarter for East London Poor Law unions from 1859 to 1870. In East London as a whole, the number of relief recipients nearly doubled from late December 1864 to the same time in 1867. In Poplar, numbers on relief more than tripled over these three years. Expenditures on poor relief for years ended on Lady Day are shown in panel (b). From 1865 to 1868 spending increased by 70% in the eight unions. It rose by 144% in Poplar, 99% in Hackney, and 95% in Bethnal Green.81

The resulting strain on East End Poor Law unions was enormous. Poor rates increased sharply in response to the increased demand for relief (Table 2.6). For the year ending March 25, 1868, poor rates in the East End ranged from 2.75s. in the pound in Shoreditch to 3.48s. in Bethnal Green. The increase was not felt equally throughout London—the poor rate averaged only 1.56s. in the pound in the metropolis as a whole, and remained below 1s. in some wealthy West End unions.

The increase in poor rates led to a sharp rise in defaults—thousands of taxpayers in East End districts were unable to pay their rates. The Select Committee on Metropolitan Local Government reported in 1866 that “so heavy has the charge of local taxation become in the less wealthy districts, that the Metropolitan Board [of Works] is of opinion that direct taxation on the occupiers of property there has reached its utmost limits,” and the Poor Law Board admitted that others had reached a similar conclusion.82 In 1866–67 boards of guardians throughout the East End turned to the Poor Law Board and the West End for assistance. London’s wealthier districts responded generously but in an uncoordinated fashion. A Mansion House Relief Fund was established and distributed over £15,000 to the poor in eastern districts, and many additional relief agencies were established. J.R. Green, a vicar in Stepney, wrote in December 1867 that “a hundred different agencies for the relief of distress are at work over the same ground, without concert or co-operation, or the slightest information as to each other’s exertions.” He added: “What is now being done is to restore the doles of the Middle Ages. The greater number of the East-end clergy have converted themselves into relieving officers. Sums of enormous magnitude are annually collected and dispensed by them either personally or through district visitors.”83

The indiscriminate nature of charitable relief appalled many middle-class observers. Sir Charles Trevelyan lamented the effects of “the wholesale, indiscriminate action of competing [charitable] societies” in an 1870 letter to the Times. In his view, “the pauperized, demoralised state of London is the scandal of our age.” The effect of indiscriminate charity was “to destroy, in large classes of our people, the natural motives to self-respect and independence of character, and their kindred virtues of industry, frugality, and temperance.” In late December 1867 Green wrote, “It is not so much poverty that is increasing in the East as pauperism, the want of industry, of thrift, of self-reliance … what is really being effected by all this West-end liberality is the paralysis of all local self-help.” Two weeks later, Green maintained that “some half a million of people in the East-end of London have been flung into the crucible of public benevolence, and have come out of it simply paupers…. The very clergy who were foremost in the work of relief last year stand aghast at the pauper Frankenstein they have created.”84

Some contemporaries blamed the boards of guardians in East End unions for creating much of the distress of 1866–68. The guardians’ objective, according to this view, was to assist the poor at the lowest possible cost to local taxpayers. Since it cost more to relieve the poor in workhouses than in their homes, guardians offered outdoor relief to the able-bodied. This was a “shortsighted economy,” since the abandonment of the workhouse test made it difficult to discriminate between the “worthy” and “unworthy” poor, and led to a sharp increase in demand for relief. Given the fiscal constraint they faced, guardians’ only possible response to the high demand was to lower the benefits offered to applicants to an amount too small to live on. According to Edward Denison, the low level of benefits led to the rise of private charity.85

Others defended the guardians’ actions, contending that the number of able-bodied adults driven by unemployment to apply for poor relief was far larger than the capacity of East End workhouses, making the workhouse test impossible to administer. According to this view, guardians dealt with the enormous demand for relief as best they could, by giving applicants small amounts of outdoor relief. Some contemporaries maintained that the problem lay not with the guardians but with the actions of local charities. Green wrote that “there are, in fact, considerable local resources, but they can only be obtained by a large system of charity… dispensed by local agencies.” This was unfortunate, because the administrators of charitable funds were less able than the guardians to discriminate “between real poverty and confirmed mendicancy.” Green concluded that it would have been far better had the “public benevolence” been used to supplement “the funds which the Boards of Guardians now devote to out-door relief,” rather than distributed separately from poor relief.86

A third group maintained that the crises of 1860–61 and 1866–68 largely were due to the method used to fund poor relief. Several who testified before the Select Committee on Poor Relief noted the large differences in poor rates across London unions and argued that if rates were equalized within the metropolis the increased demand for relief could have been handled by the Poor Law alone, without need for the flood of indiscriminate charity. The vice-chairman of the City of London union, Robert Warwick, stated in 1861 that “the poor of London are the poor of the whole metropolitan community, and not of the particular parish” in which they live. The East End dockworker or the Bethnal Green weaver labored “more for the benefit of the city merchant, or the west-end resident, than for his own neighbours;… those who have benefit of his labour ought to bear a fair share of the relief required in the time of his distress.” He added that “the equalization of the poor rate throughout London would be an immense benefit to all classes of the community, and one of justice both to the poor and ratepayer.”87

Warwick also was Secretary of the Society for the Equalization of the Poor Rates, founded in 1857 to promote the sharing of the cost of poor relief across London unions. Six members of the society’s Executive Committee testified before the Select Committee on Poor Relief, and their statements helped persuade the committee to “recommend the general question of extending the area of rating to the further consideration of the House.”88 In response to the crises in 1860–61 and 1866–67, the lobbying of the Society for the Equalization of the Poor Rates, and appeals from various ratepayers’ associations, Parliament adopted the Metropolitan Poor Act in March 1867. The act created the Metropolitan Common Poor Fund (MCPF), to which all London unions contributed according to the value of their rateable income. Not all relief expenditures were transferred from the union to the MCPF. The act stipulated that some medical expenses, the cost of maintaining lunatics in asylums and pauper children in schools, and the relief of the casual poor were to be paid out of the common fund. An amendment in 1870 added a subsidy of 5d. per person per day for adult paupers in workhouses; no subsidy was provided for adults receiving outdoor relief.

The MCPF, which came into operation in September 1867, led to a redistribution of income from wealthy metropolitan districts to working-class districts, although it did not equalize poor rates across unions.89 The effects of the MCPF on poor rates for fiscal year 1868 can be seen by comparing the columns labeled 1868(a) and 1868(b) in Table 2.6. The poor rate for Bethnal Green in 1867–68 was 3.48s. in the pound; in the absence of the transfer from the MCPF, the same expenditure on relief would have required a poor rate of 3.92s. in the pound. On the other hand, the poor rate for Kensington increased from 0.92s. to 1.02s. in the pound as a result of its contribution to the MCPF. The final column of Table 2.6 shows the net amount received from (or contributed to) the MCPF during the 18 months from September 1867 to March 1869. The wealthy unions of Kensington, Paddington, and St. George Hanover Square contributed over £42,000 to the MCPF during this period, while the East End unions of Shoreditch, Bethnal Green, Whitechapel, St. George in the East, and Stepney received nearly £53,000. Despite this substantial redistribution of income, there remained large differences in poor rates across unions, and rates remained very high in working-class districts. The adoption of the MCPF ameliorated the crisis of 1866–69 in East London, but it did not solve the problem inherent in the system.

V. Conclusion

The New Poor Law was supposed to usher in an era of self-help, in which manual workers protected themselves against income loss by increasing their saving and joining friendly societies. Its supporters assumed that, as a result of the increase in self-help, demand for poor relief by working-class households would greatly decline, even during downturns, and the Poor Law’s main job would be to assist widows and orphans, the non-able-bodied, and the elderly. This assumption proved to be wide of the mark. Working-class self-help did indeed increase after 1834, but few households were able to save more than a small amount, and spells of unemployment lasting more than a few weeks exhausted most workers’ savings. Large numbers of workers continued to turn to the Poor Law during economic crises, and Poor Law unions continued to provide outdoor relief to the unemployed and their families.

The Poor Law’s inability to cope financially with the increased demand for relief during crises led to the rise of short-term large-scale charitable movements to assist those in need. These charities invariably were a mixed blessing—they were able to raise large amounts of money quickly, but they proved to be less successful at distributing it, often handing out relief in an indiscriminate manner to all comers.

The breakdown of the Poor Law in the 1860s, together with the unsystematic nature of charitable aid, convinced many that the system of poor relief required a “radical restructuring,” and that the way to restore self-help among the poor was to greatly restrict the provision of outdoor relief and strictly regulate the provision of private charity. In the decade that followed, major changes in the Poor Law were undertaken that significantly altered the form of public assistance for working-class households.

Appendix 2.1

For the first 40 years of the nineteenth century data on the number of poor relief recipients exist only for 1802–3 and 1812–13 through 1814–15. The data reported for 1802–3 include children permanently relieved outdoors, but those for 1812–15 do not. For reasons that are not given, the questionnaire sent to parishes at the later date specifically stated that children whose parents were permanently relieved outdoors should not be reported, although children of persons permanently relieved in workhouses are included in the returns for 1812–15. It is not clear whether children of persons relieved occasionally are included in either the 1802–3 or 1812–15 returns. For each year 1812–13 to 1814–15, I estimated the number of children permanently relieved outdoors, by assuming that the ratio of children to adults permanently relieved outdoors was equal to that for 1802–3. I then added the estimated number of children relieved to the reported number receiving relief for each year 1812–13 to 1814–15. This increases the average share of the population relieved for the three years from 8.9% to 12.6%.

Annual relief expenditure data are available from 1812–13 onward. The average annual expenditure per relief recipient for 1812–13 through 1814–15, calculated by dividing real expenditures for England and Wales by the number receiving relief, was £4.714. Assuming that this ratio held until 1834, I calculated crude estimates of the annual number of persons receiving poor relief from 1815–16 to 1833–34 by dividing annual real relief expenditures by 4.714. I used the estimated numbers on relief to calculate the annual share of the population receiving poor relief, reported in Table 2.A.1 and Figure 2.1.90 The share receiving relief averaged 15.1% for 1812–33; it varied from a low of 11.8% in 1814 to a high of 17.1% in 1817.

Table 2.A.1 also presents annual estimates of relief expenditures for England and Wales as a share of gross domestic product for 1812–50. The construction of these estimates is explained in Appendix 1.3.

1. Lindert (1998: 114); Boyer (2002: Table 1). On the pre-1834 role of the Poor Law in grain-producing parishes, see Boyer (1990: chaps. 3–5).

2. Eden (1797: 1:447–48); Malthus ([1798] 2008: 40–41).

3. Royal Commission to Investigate the Poor Laws, Report on the Administration and Practical Operation of the Poor Laws (1834: 261–63).

4. Driver (1989). On northern opposition to implementing the New Poor Law, see Edsall (1971) and Knott (1986). On the opposition in southern rural districts, see Digby (1975; 1978).

5. Annual estimates of Poor Law expenditures as a share of GDP for 1812–50 are reported in Appendix 2.1. My estimates differ slightly from those by Lindert (1998: 113–15) because I use more recent GDP estimates.

6. See Hunt (1981: 215), Rose (1966: 612–13), and Rose (1970: 121–43). Lees (1998: chap. 6) found that in three London parishes and six provincial towns in the years around 1850 large numbers of prime-age males continued to apply for relief, and that a majority of those assisted were granted outdoor relief. Digby (1975) presents evidence that restrictions on granting outdoor relief to able-bodied males also were evaded by rural Poor Law unions in the grain-producing East.

7. Gorsky (1998: 493); King and Tomkins (2003: 267).

8. Data for 1815 from Gorsky (1998: 493–97); data for 1821 from Gosden (1961: 22–24).

9. Gorsky (1998) discusses various explanations for the regional nature of friendly society membership in the first third of the nineteenth century. See also King and Tomkins (2003: 266–68).

10. Neave (1996: 46–47); Gosden (1973: 27–30).

11. The quote is from Fishlow (1961: 32). Johnson (1985: 103) considered £50 to be “an upper limit for most working-class savings bank deposits” in 1911–13. Given the large increase in wages from 1830 to 1911, the upper limit for working-class savings must have been far below £50 in 1830; using this number as a cutoff provides an upper-bound estimate of the importance of working-class saving.

12. Fishlow (1961: 32). Johnson (1985) presents evidence that about 30% of savings bank deposits were held by workers in the decades leading up to World War I. Assuming that 30% of deposits were held by workers in 1830 gives an unreasonably large average account balance. My estimate of £3.2 million assumes that manual workers held all deposits under £20 and half of the deposits between £20 and £50, and that the average working-class balance for this larger category of deposits was £25.

13. Poor relief expenditures in England and Wales totaled £6.8 million in 1830, but some of this was for administration. In 1840, spending on indoor and outdoor relief represented 82% of total relief spending. Applying this same ratio to 1830 yields an expenditure level of about £5.6 million.