Unemployment and

Unemployment Relief

The existence of unemployed workers was not a new phenomenon, nor was the unemployment rate necessarily higher, on average, after the onset of industrialization than before. But the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of the business cycle and cyclical downturns, and contemporaries viewed large-scale involuntary unemployment as “the characteristic disease of the modern industrial system.” The second half of the century saw the rise of another “modern evil”—a growth in the number of chronically underemployed low-skilled laborers in London and urban industrial centers. By the beginning of the twentieth century, contemporary observers concluded that in many large towns the supply of low-skilled workers was larger than the demand for labor “even in times of brisk trade.” The threat of income loss due to unemployment was a major cause of economic insecurity for manual workers. In the words of Beveridge, “society is built up on labour; it lays upon its members responsibilities which in the vast majority of cases can be met only from the reward of labour. . . . Reasonable security of employment for the bread-winner is the basis for all private duties and all sound social action.”1

Most urban boards of guardians continued to assist cyclically unemployed workers through the late 1860s, despite Parliament’s attempt in 1834 to restrict the granting of outdoor relief to able-bodied males. However, the Crusade Against Outrelief led to a major change in public policy toward the unemployed—after the early 1870s most urban Poor Law unions offered unemployed workers relief only in workhouses. During major downturns local governments and charities adopted ad hoc methods for relieving the unemployed, and many skilled workers received unemployment benefits from trade unions. The new solution proved no better at relieving the nonunionized unemployed, or preventing unemployment, than the Poor Law had been. The amount of assistance offered to individual workers typically was quite small, and only a minority of the unemployed—mostly unskilled laborers—applied for and received relief. The problems associated with relying on ad hoc emergency relief funds became apparent during the downturn of 1885–86, and the Local Government Board responded by encouraging municipalities to set up work relief projects to aid the unemployed. However, the downturns of 1893–96 and 1904–5 revealed the inability of municipal work-relief programs to adequately assist temporarily unemployed workers. From 1886 onward, each business-cycle downturn put additional pressure on Parliament to adopt a national system of unemployment relief.

For most of the century, middle-class observers believed that, except during severe downturns, the majority of those out of work were voluntarily unemployed. A shift in public attitudes occurred in the decades leading up to the First World War; the extent of this shift can be seen in the title of Beveridge’s influential 1909 book, Unemployment: A Problem of Industry. Beveridge rejected the view that any able-bodied adult who wanted work could readily find a job. Unemployment was caused by cyclical and seasonal fluctuations in the economy and maladjustments of supply and demand for labor, not by the deficiencies of individual workers. The shift in public opinion, along with the failure of local relief policies, paved the way for the adoption of national unemployment insurance.

The chapter proceeds as follows. Section I examines the extent of cyclical, seasonal, and casual unemployment from 1870 to 1913. Section II describes trade unions’ unemployment benefit policies, and the shift in measures used by local authorities and private charities to assist the unemployed from the Crusade Against Outrelief until the adoption of national unemployment insurance in 1911.

I. The Extent of Unemployment, 1870–1913

In 1905 the Board of Trade constructed an unemployment index back to 1860 using information supplied to it by trade unions, and Feinstein incorporated the series into his estimates of unemployment for 1855–1913. The Board of Trade index has serious shortcomings, as Feinstein and others have noted.2 In 2002 Boyer and Hatton constructed new estimates of the industrial unemployment rate from 1870 to 1913, relying chiefly on trade union records but incorporating other information where possible in order to include sectors for which union unemployment data are not available. They combined unemployment series for 13 broad industrial sectors to form an aggregate series using labor force weights based on Lee’s reworked census totals for males employed in industry.3

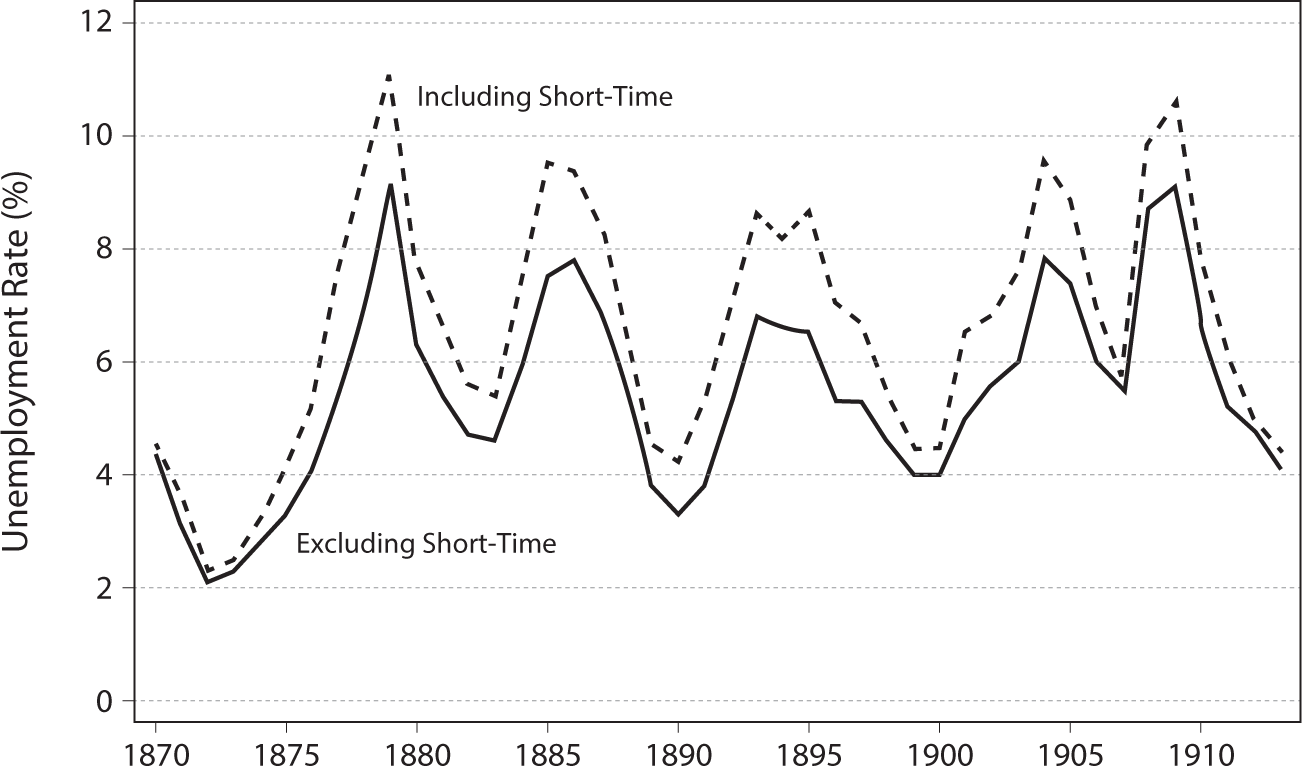

Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1 report two versions of the aggregate Boyer and Hatton index, including and excluding employment loss from short-time work, which was common in mining and textiles. The average unemployment rate for 1870 to 1913 was 6.6% when employment loss from short time is included and 5.4% when it is excluded. The effect of including short time is large because mining and textiles were large sectors—in 1901 they account for a quarter of the workforce included in the index—in which the number of “wholly unemployed” workers “substantially under-stated the true volume of unemployment.”4 When employment loss from short-time work is included, the unemployment rate exceeded 8% in 1878–79, 1885–87, 1893–95, 1904–5, and 1908–9, more than a quarter of the years from 1870 to 1913.

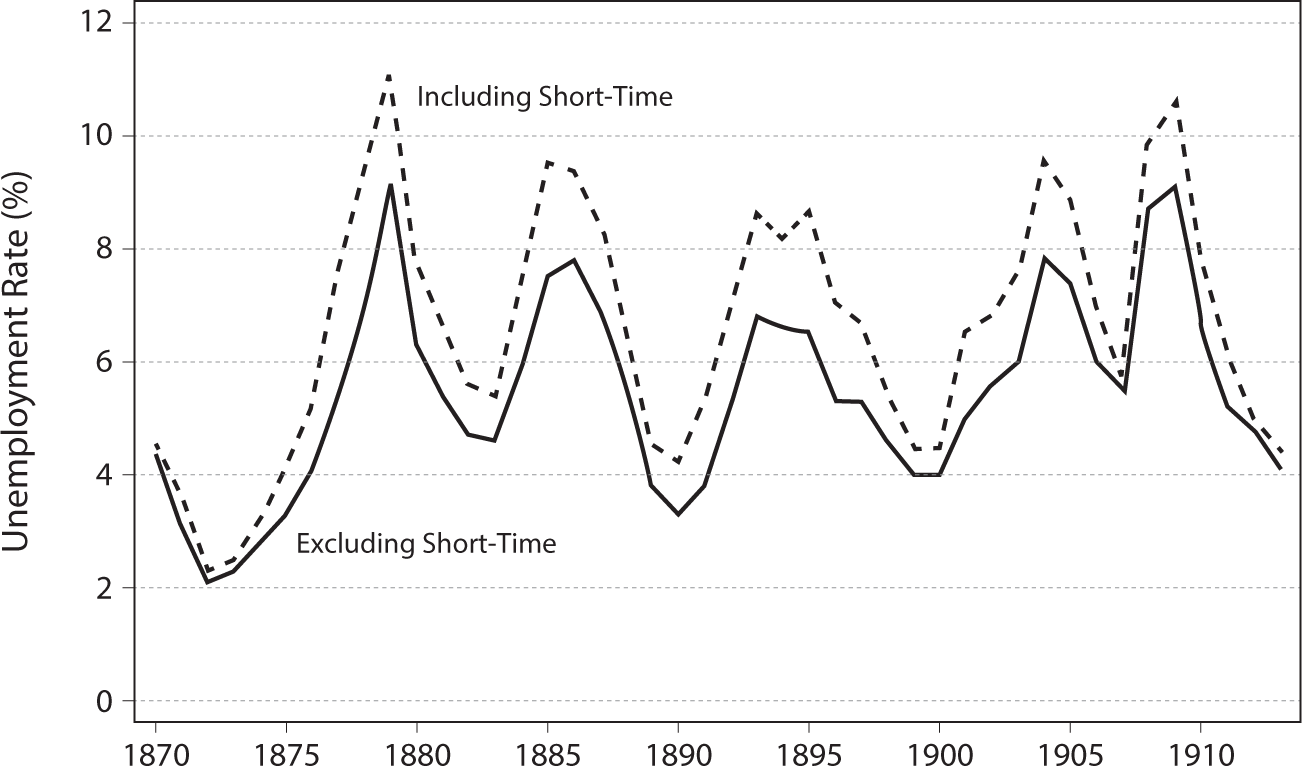

Unemployment varied substantially across sectors. For 1870–1913, it was highest in mining (11.3%), shipbuilding (8.7%), metals (6.7%), textiles (7.0%), and general unskilled labor (9.5%), and lowest in woodworking (3.1%), printing and bookbinding (3.7%), clothing and footwear (3.8%), and carriage and wagon (3.8%).5 It is useful to examine a few sectors in more detail. Figure 4.2 presents the unemployment series for two large sectors—metals and the building trades. While the two series move in a similar pattern, at least through 1903, the average unemployment rate was higher and the severity of cyclical fluctuations larger in metals than in construction. The other major difference between the two series is their trends over time. From 1870 to 1898, the average unemployment rate was much higher in metals (6.7%) than in the building trades (3.9%). Unemployment in construction increased sharply thereafter, while that for metals remained roughly constant, so that for 1899–1913 the average unemployment rate in the two sectors was nearly identical—6.8% in metals and 6.7% in construction.

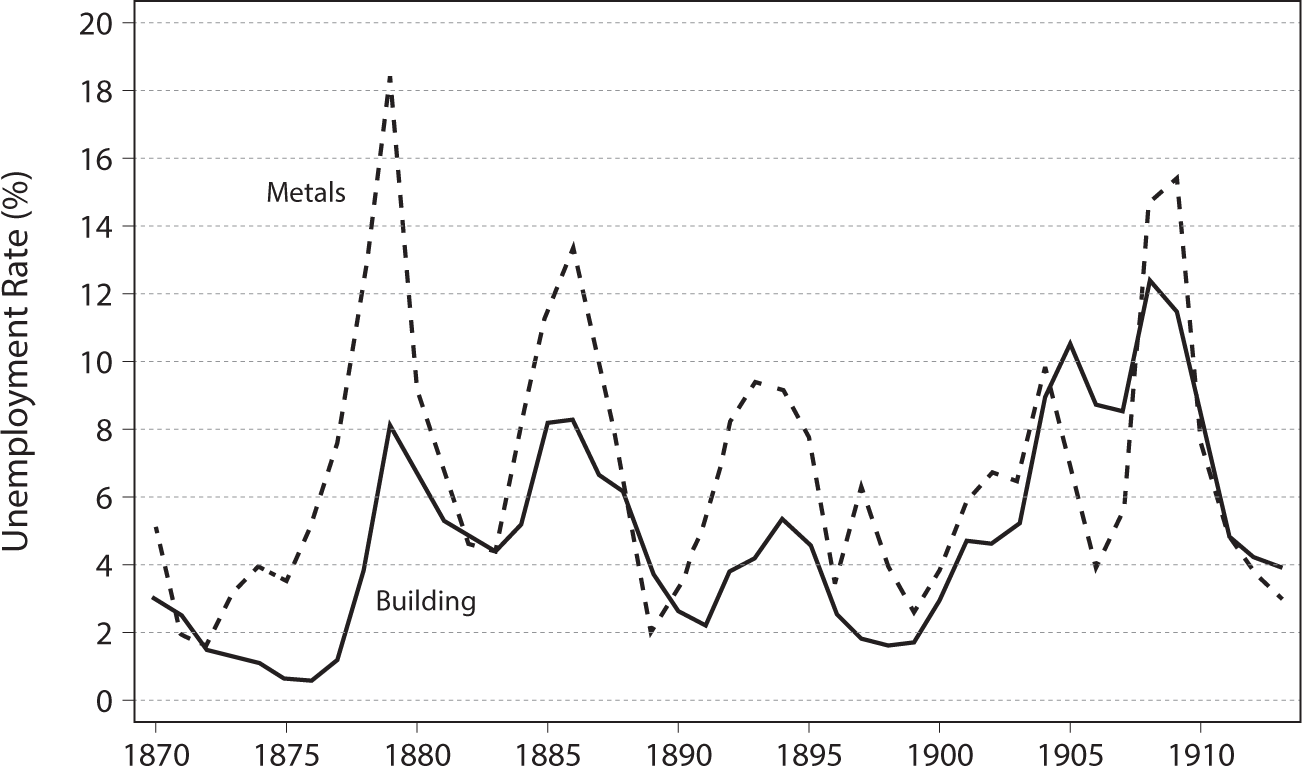

Mining was an important and growing sector during this period, employing over one million workers in 1911. Figure 4.3 presents unemployment series for mining both including and excluding employment loss from short-time working. Wide fluctuations in the demand for labor were accommodated largely by short-time rather than layoffs. According to the Labour Gazette, the “state of employment” in coal mining was “best gauged, not by the proportion of workpeople entirely unemployed, but by the average number of days per week on which work is available. . . . Except in times of great depression or expansion of trade, fluctuations in demand are met rather by working more or fewer days per week, than by the engagement of more or fewer men.” From 1870 to 1913, the average number of days worked per week was 5.2, varying from a maximum of 5.87 in 1873 to a minimum of 4.63 in 1877–78. The average unemployment rate for 1870–1913, including short time, was 11.3%, nearly twice the unemployment rate excluding short time (5.9%).6

TABLE 4.1. Unemployment Rates, 1870–1913: Two Variants and the Board of Trade Index |

|||

Year |

Excluding Short Time |

Including Short Time |

Board of Trade |

1870 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

3.7 |

1871 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

1.6 |

1872 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

0.9 |

1873 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

1.1 |

1874 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

1.6 |

1875 |

3.3 |

4.1 |

2.2 |

1876 |

4.1 |

5.2 |

3.4 |

1877 |

5.4 |

7.7 |

4.4 |

1878 |

7.0 |

9.5 |

6.2 |

1879 |

9.1 |

11.1 |

10.7 |

1880 |

6.3 |

7.7 |

5.2 |

1881 |

5.4 |

6.5 |

3.5 |

1882 |

4.7 |

5.6 |

2.3 |

1883 |

4.6 |

5.4 |

2.6 |

1884 |

5.9 |

7.3 |

8.1 |

1885 |

7.5 |

9.5 |

9.3 |

1886 |

7.8 |

9.4 |

10.2 |

1887 |

6.9 |

8.4 |

7.6 |

1888 |

5.6 |

6.7 |

4.9 |

1889 |

3.8 |

4.5 |

2.1 |

1890 |

3.3 |

4.2 |

2.1 |

1891 |

3.8 |

5.3 |

3.5 |

1892 |

5.2 |

7.0 |

6.3 |

1893 |

6.8 |

8.6 |

7.5 |

1894 |

6.6 |

8.2 |

6.9 |

1895 |

6.5 |

8.6 |

5.8 |

1896 |

5.3 |

7.0 |

3.3 |

1897 |

5.3 |

6.7 |

3.3 |

1898 |

4.6 |

5.4 |

2.8 |

1899 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

2.0 |

1900 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

2.5 |

1901 |

5.0 |

6.5 |

3.3 |

1902 |

5.6 |

6.8 |

4.0 |

1903 |

6.0 |

7.6 |

4.7 |

1904 |

7.8 |

9.6 |

6.0 |

1905 |

7.4 |

8.9 |

5.0 |

1906 |

6.0 |

6.9 |

3.6 |

1907 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

3.7 |

1908 |

8.7 |

9.9 |

7.8 |

1909 |

9.1 |

10.6 |

7.7 |

1910 |

6.6 |

7.9 |

4.7 |

1911 |

5.2 |

6.2 |

3.0 |

1912 |

4.8 |

5.0 |

3.3 |

1913 |

4.1 |

4.4 |

2.1 |

Source: Boyer and Hatton (2002: 662). |

|||

FIGURE 4.1. Aggregate Unemployment Rates, 1870–1913

FIGURE 4.2. Unemployment in Metals and Building Trades, 1870–1913

FIGURE 4.3. Unemployment in Mining, 1870–1913

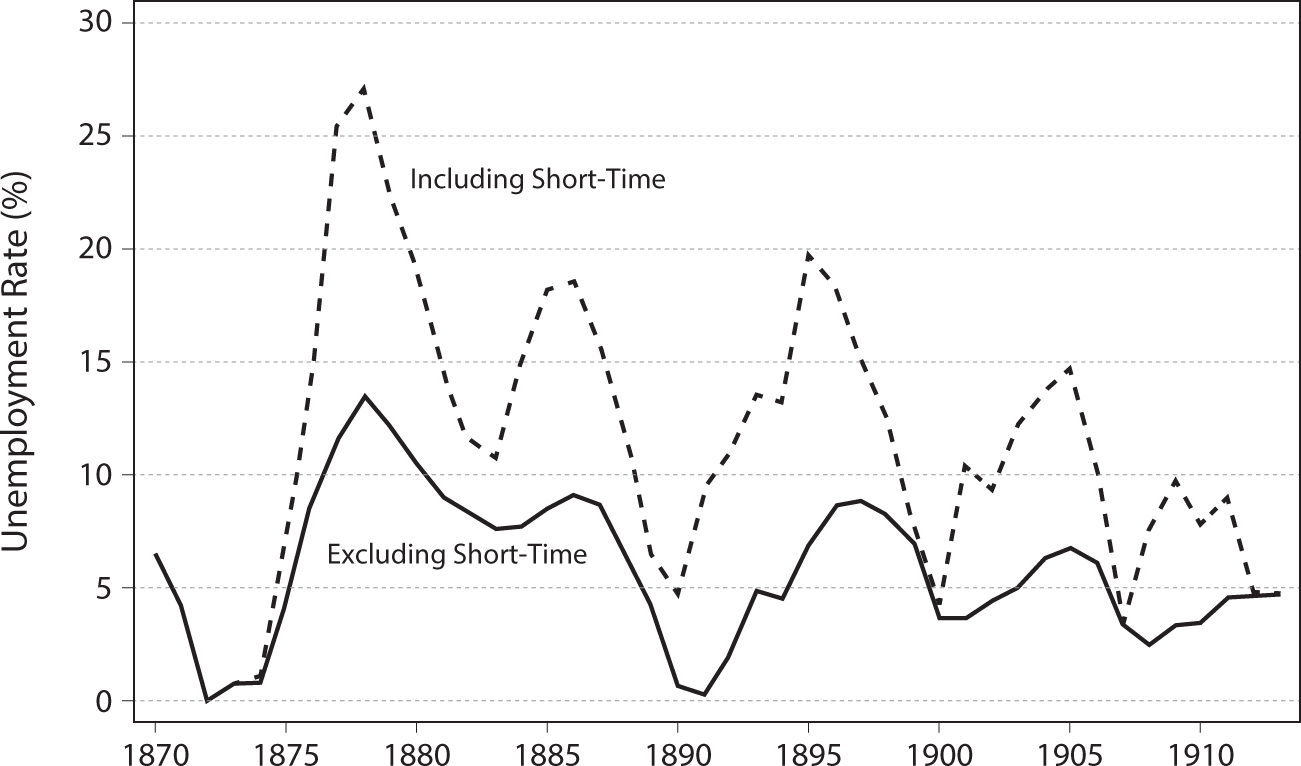

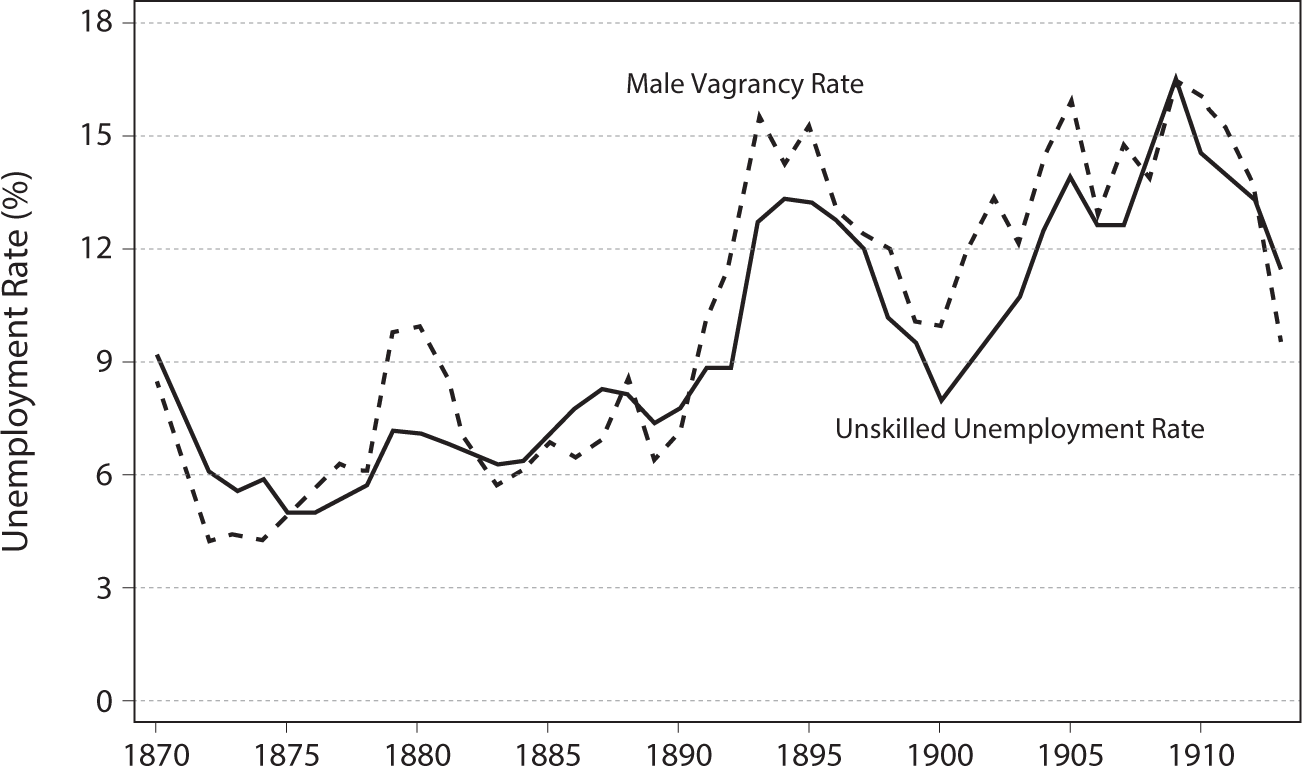

Unemployment data for unskilled workers do not exist. Following MacKinnon, Boyer and Hatton constructed an unemployment series for general unskilled laborers using time-series data for male able-bodied indoor paupers as a share of the male population aged 15–64.7 The estimated unemployment series for general unskilled laborers is presented in Figure 4.4. The series follows the same cyclical pattern as the other sectoral series, except that unemployment among unskilled laborers increased sharply over time—the unemployment rate was below 10% in every year from 1870 to 1892, then above 10% in all but four years from 1893 to 1913. Figure 4.4 also presents an unemployment series constructed using vagrancy data.8 Vagrants were typically adult males under age 60. While not all vagrants were in search of work, their numbers increased during downturns and declined during booms, suggesting that a substantial share were in fact unemployed men “forced to migrate in search of work.”9 The unemployment series constructed using vagrancy data is quite similar to that constructed using data for male indoor paupers. These series indicate that employment opportunities for casual and general laborers deteriorated—both absolutely and relative to those of skilled workers—during the last two decades before the First World War.10

FIGURE 4.4. Unemployment for Unskilled Laborers, 1870–1913

Contemporary observers agreed that unemployment rates were higher for the unskilled than for skilled workers. The Boyer and Hatton estimates show that the average unemployment rate for unskilled workers in 1870–1913 was 50% greater than that for skilled and semiskilled workers. The aggregate unemployment rate is a poor measure of the extent of economic insecurity among the unskilled.11

Annual unemployment rates give an idea of the average level of distress among manual workers in a given year, but they greatly understate the share of workers who were unemployed at some point during a year. Table 4.2 presents data on the distribution of unemployment among skilled workers in four trade unions. For each union, data are given for a year of low unemployment and a year of high unemployment; for the Amalgamated Engineers, data also are given for the average of nine years from 1887 to 1895. Even during prosperous years, nearly one in five skilled workers experienced some income loss due to unemployment. The average unemployment rate among engineers for 1887–95 was 6.1%, but nearly 30% were unemployed during a calendar year. Some 12.0% of union members were unemployed for at least eight weeks during a year, and 9.3% were unemployed for twelve or more weeks. The data for the Carpenters and Joiners, London Compositors, and Woodcutting Machinists yield similar results. The unemployment rate for the Carpenters and Joiners was 6.0% in 1904–5, but 43.1% of members were unemployed at some point in the year, and 15.9% were unemployed for at least eight weeks.

TABLE 4.2. Distribution of Unemployment in Four Trade Unions |

|||||||||

|

Amalgamated Engineers (Manchester and Leeds) |

Carpenters and Joiners |

London Compositors |

Woodcutting Machinists |

|||||

|

1887–95 |

1899 |

1904 |

1898–99 |

1904–5 |

1898 |

1905 |

1898 |

1904 |

Unemployment rate |

6.1 |

3.0 |

7.6 |

1.1 |

6.0 |

2.8 |

5.0 |

1.4 |

4.3 |

% unemployed at some time in year |

29.7 |

18.6 |

35.0 |

19.7 |

43.1 |

17.9 |

22.4 |

22.1 |

33.7 |

Days lost per member |

18.7 |

9.1 |

23.3 |

3.4 |

18.8 |

8.9 |

15.7 |

4.5 |

13.4 |

Days lost per unemployed member |

63.1 |

49.1 |

66.5 |

17.4 |

43.6 |

49.5 |

70.3 |

20.5 |

39.8 |

% unemployed for 4 weeks or more |

16.7 |

9.1 |

21.1 |

4.3 |

24.3 |

11.5 |

16.0 |

5.7 |

16.6 |

% unemployed for 8 weeks or more |

12.0 |

5.6 |

15.0 |

1.7 |

15.9 |

7.3 |

11.5 |

2.9 |

10.6 |

% unemployed for 12 weeks or more |

9.3 |

3.8 |

11.0 |

0.7 |

9.5 |

4.7 |

8.3 |

1.4 |

7.2 |

Sources: Parl. Papers, British and Foreign Trade and Industrial Conditions (1905, LXXXIV), p. 101; Parl. Papers, Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress. Statistics Relating to England and Wales (1910, LIII), pp. 870–76. |

|||||||||

For each of the unions, the share of workers unemployed for at least eight weeks a year was roughly double the annual unemployment rate. The distribution of unemployment for the four unions probably overstates the share of workers who experienced income loss due to unemployment in stable industries such as the railways; on the other hand, it understates the share who experienced income loss in metals and shipbuilding, and among general unskilled laborers. If the data are reasonably representative of the incidence of unemployment among all manual workers in late Victorian England, then during bad years on average nearly 15% of manual workers were unemployed for eight or more weeks, and nearly one in ten were unemployed for at least twelve weeks. The threat of being unemployed for two months or longer within a calendar year was far higher than the annual unemployment estimates suggest.

Seasonal unemployment differed from cyclical unemployment in that it was to a large degree predictable. Economists since Adam Smith have argued that workers in seasonal occupations were paid higher daily or hourly wages than similarly skilled workers to compensate for their periodic spells of unemployment. Even if seasonal industries paid compensating wage differentials, however, seasonal unemployment still created insecurity, especially among low-skilled workers who found it difficult to save enough from their peak-season earnings to carry them through slack seasons.

The extent of nonagricultural seasonal unemployment is difficult to measure precisely. Table 4.3 presents evidence from the early twentieth century on the extent of seasonal fluctuations in employment for five industrial sectors. The first two columns present indices of monthly employment in the building trades in 1907–10. Column 3 presents an index of the total amount of wages paid to building workers in each month. The magnitude of the seasonal fluctuation in wage income is larger than in employment because the workweek was slightly shorter in winter. The wage income of construction workers was, on average, 17–24% lower from November to February than it was in May. The extent of seasonal fluctuations in labor demand varied across sections of the building trade, being relatively low for plumbers and especially high for bricklayers and painters.12

TABLE 4.3. Seasonality of Employment in Five Sectors |

|||||||

|

BUILDING TRADES |

COAL MINERS |

GAS WORKERS |

FURNISHING TRADES |

TOBACCO WORKERS |

||

|

Skilled Men |

Laborers |

All Men |

|

|

|

|

|

Number Employed 1907–10 |

Number Employed 1907–10 |

Wage Income 1906 |

Days Worked per Week 1897–1911 |

Number Employed 1906 |

Unemployment Rate 1897–1906 |

Unemployment Rate 1897–1906 |

January |

84.4 |

84.0 |

76.2 |

5.20 |

97.2 |

7.9 |

5.8 |

February |

89.0 |

87.7 |

82.7 |

5.43 |

93.9 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

March |

94.5 |

92.5 |

92.6 |

5.39 |

89.1 |

3.3 |

7.4 |

April |

96.3 |

95.3 |

97.6 |

5.03 |

85.5 |

2.4 |

7.8 |

May |

96.3 |

96.2 |

100.0 |

5.23 |

84.2 |

2.5 |

8.3 |

June |

94.5 |

95.3 |

96.5 |

4.92 |

83.0 |

3.2 |

8.6 |

July |

96.3 |

98.1 |

96.6 |

4.98 |

83.6 |

4.1 |

9.3 |

August |

100.0 |

100.0 |

98.7 |

4.99 |

84.4 |

4.1 |

9.4 |

September |

95.4 |

96.2 |

96.3 |

5.35 |

87.8 |

4.2 |

7.3 |

October |

89.0 |

90.6 |

91.3 |

5.41 |

92.3 |

4.5 |

5.1 |

November |

86.2 |

87.7 |

82.6 |

5.39 |

97.2 |

4.9 |

3.2 |

December |

80.7 |

82.1 |

78.7 |

5.47 |

100.0 |

7.1 |

4.7 |

Sources: Columns 1 and 2: Webb (1912: 334). Column 3: Board of Trade, Earnings and Hours of Labour . . . Building and Woodworking Trades (1910: 13). Column 4: Data for 1897–1901 from Board of Trade, Eleventh Abstract of Labour Statistics (1907: 5). Data for 1902–11 from Board of Trade, Fifteenth Abstract of Labour Statistics (1912: 9). Column 5: Popplewell (1912: 196). Columns 6 and 7: Poyntz (1912: 23–24). Notes: The series in columns 1, 2, and 5 are indices; the index numbers show each month’s employment as a percentage of the peak month’s employment. The series in column 3 is an index; the index numbers show each month’s wage income as a percentage of the peak month’s wage income. |

|||||||

Seasonality in mining typically was handled by reducing the number of shifts worked per week in slack seasons rather than by laying off workers. From 1897 to 1911, the average number of days worked per week varied from 5.47 in December to 4.92 in June. Employment at gas works was highly seasonal, with 11–17% fewer workers employed from March to September than in December. In the furnishing trades, unemployment varied from a low of 2.5% in April and May to over 7% in December and January; in tobacco, unemployment exceeded 9% in July and August, but was 3.2% in November. Other trades experienced less pronounced seasonal fluctuations in labor demand; a 1909 Board of Trade memorandum concluded that “seasonal fluctuation is found to a more or less marked degree in nearly every industry.”13

Systems of temporary or casual employment developed in some low-skilled occupations that were subject to sudden and irregular fluctuations in labor demand. Casual employment existed to some degree among painters and unskilled laborers in the building trades, and among workers in land transport, menial services, and certain declining manufacturing trades.14 It was especially pronounced among dockworkers, due to the irregularity in the arrival and departure of ships. Dockworkers were hired by the day or half day, chosen by foremen each morning and afternoon from groups of workers at calling-on stands. As a result employment was extremely intermittent, and apart from a minority who were regularly employed, most dockworkers spent a substantial proportion of the year unemployed. Booth found that in 1891–92 approximately 22,000 men regularly competed for work at the London docks, and that the average number employed per day was 15,175.15 Thus, on an average day upward of 6,800 London dockers were without work. A 1908 Charity Organisation Society Report on Unskilled Labour concluded that “the independent action of the separate employing agencies, each seeking to retain a following of labour as nearly as possible equal to its own maximum demand” led to “the maintenance of a floating reserve of labour far larger than is required to meet the maximum demands of employers . . . [and] a mass of men chronically under-employed.”16 A large share of dockworkers suffered chronic distress as a result of their irregularity of employment.

The method of hiring painters and low-skilled laborers in the building trades was similar to that of the docks, except that there were no fixed calling-on stands and workers were hired by the job rather than the day. Hiring was done by foremen at job sites. A foreman would start a new job with a few “permanent” employees and hire more workers as they arrived at the job site, “guided by recommendations from their mates or stray hints in public houses . . . [or] tramping without guidance about likely districts.” Hiring typically was done on a first-come first-served basis—workers who proved unsatisfactory were fired after a few days or weeks and replaced by newcomers. This system led to the creation of “a floating mass of labour . . . drifting perpetually about the streets” in search of work. Robert Tressell, in The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, described the process as follows: “It is usual for [casual hands] to put in a month with one firm, then a fortnight with another, then perhaps six weeks somewhere else, and often between there are two or three days or even weeks of enforced idleness.” Beveridge concluded that, while distress among dockworkers was chronic, among building laborers it was “recurrent, with bad weather or the end of a job.”17

In sum, the possibility of employment loss faced by manual workers was far greater than the aggregate unemployment estimates suggest. A majority of workers lost no time due to unemployment within a calendar year, but a substantial minority lost several weeks of work even during years of low unemployment. Low-skilled workers were the most likely to suffer income loss due to unemployment, and before 1870 they also had relied most heavily on the Poor Law for assistance when unemployed. Section II examines the major changes in the forms of income assistance for the unemployed brought about by the Crusade Against Outrelief.

II. Unemployment Relief, 1870–1911

After 1870 trade unions became a major source of unemployment benefits for skilled workers, who became less and less likely to turn to local authorities or charitable institutions for assistance. On the other hand, low-skilled workers continued to rely on public and private assistance until the First World War. The restriction of poor relief that occurred as a result of the Crusade Against Outrelief did not signal the end of local government involvement in assisting the unemployed. Beginning in 1886 the Local Government Board encouraged cities to set up work relief projects during cyclical downturns, and the idea of temporary work relief was given statutory recognition by the Unemployed Workmen Act of 1905. When examining unemployment relief during this period, it therefore is necessary to examine skilled and unskilled workers separately.

TRADE UNION UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS

Although certain craft unions began providing their members with “friendly benefits” early in the nineteenth century, the adoption of mutual insurance policies increased sharply in the third quarter of the century. A strong emphasis on mutual insurance was a characteristic of the “New Model” unionism, which began in the 1850s and by 1870 included several unions in the building trades, iron and steel, engineering, shipbuilding, printing, and elsewhere. Unemployment benefits were the most important of the union-provided insurance benefits because they typically were not offered by friendly societies. Workers anxious to insure themselves against unemployment could do so only through a trade union.18

Why didn’t friendly societies provide benefits to unemployed members? There were moral hazard issues associated with the provision of unemployment benefits. An insuring organization had to determine whether a member who applied for relief was in fact eligible for benefits, and whether benefit recipients were actively searching for work. Most craft unions eliminated this moral hazard by forcing applicants to make their claims for benefits at branch meetings in front of fellow workmen, and those deemed eligible had to sign their branch’s “vacant book” every day. Branch secretaries directed unemployed members to local firms in need of labor, and members who did not apply for a job when informed of a vacancy or refused a job offer forfeited their unemployment benefits. The cost of monitoring members’ eligibility for benefits and search activity, and of finding work for unemployed members, was far higher for friendly societies than for trade unions because their membership typically belonged to several occupations. Contemporaries recognized the unique ability of trade unions to reduce moral hazard. The Webbs maintained, “Out of Work pay cannot be properly administered except by bodies of men belonging to the same trade and working in the same establishments.” Similarly, Beveridge concluded that unions “come nearer than any other bodies to possessing a direct test of unemployment by which to protect their funds against abuse. . . . They are better able, therefore, than anyone else at the present time to assist the unemployed on honourable terms without imminent risk of encouraging unemployment.”19

In 1893, 744,000 trade union members (59% of union members) were eligible for unemployment benefits. Table 4.4 shows that by 1906 more than 1,456,000 workers were eligible for unemployment benefits, representing nearly 73% of union members, but only 12% of the adult male workforce.20 The benefits took various forms. Many unions provided weekly benefits to unemployed members. Others provided “payments to members travelling in search of work, . . . payments on account of cessations of work due to fires, failures of firms, temporary stoppages and breakdowns of machinery, emigration grants (in a few instances), and special grants in times of excessive slackness.”21

The availability of unemployment benefits differed markedly across occupations. Virtually all union members in engineering, shipbuilding, cotton weaving, printing, woodworking, and glass trades were entitled to unemployment benefits, compared with 89% in the building trades, 44% in mining, and 40% in iron and steel unions. Among low-skilled workers, 29% of unionized laborers in the building trades, 20% of carmen and dock laborers, and 62% of general laborers were eligible for unemployment benefits of some sort. One must be careful in interpreting these numbers, however, because the types of unemployment benefits differed across occupations. This can be seen by examining expenditures per union member—spending was far greater in unions providing unemployed members with weekly benefits than in unions that provided only traveling benefits or occasional grants. Column 4 shows that spending per union member varied substantially across occupations. It exceeded 10s. per member for carpenters, iron founders, engineers and shipbuilders, printers, woodworkers, and glass workers. On the other hand, it was less than 3s. per member in mining and textiles, and less than 1s. per member for railway servants, building laborers, carmen and dockworkers, and general laborers. The benefits offered to low-skilled workers were quite meager.

Why didn’t all unions offer their unemployed members weekly benefits? In coal mining, textiles, and some other industries, the widespread use of short time and sliding wage scales meant that there were few layoffs except at times of “excessive slackness.” Unions of low-skilled workers did not provide unemployment benefits because the irregularity of employment in most low-skilled occupations and the typical oversupply of labor raised the cost of insurance substantially above the weekly premium paid by skilled workers and above what the unskilled could afford to pay.22

Union-provided unemployment benefits were financed by members’ weekly contributions. The typical union member paid 6d. to 1s. per week in dues. No unions maintained separate unemployment insurance funds, but it is possible to estimate the cost of unemployment insurance by calculating individual unions’ average annual expenditure per member on unemployment benefits. Such a calculation for three major unions—the Amalgamated Society of Engineers, the Amalgamated Carpenters and Joiners, and the London Compositors—for 1870–96 yields average annual expenditures on unemployment benefits per member of 22.3s., 15.3s., and 16.4s., respectively, or 3.5–5.1d. per member per week. Adding a small amount for administrative costs brings the cost to insure a skilled worker against unemployment to 4–6d. per week, which was 1–2% of his weekly income.23

The Board of Trade reported total expenditures on unemployment benefits of 100 principal trade unions for the years 1892–1910. Spending varied from a low of £184,600 in 1899 to a high of £1,004,685 in 1908; the average annual expenditure was £468,500. The Labour Department estimated that all British trade unions spent a total of £1,257,913 on unemployment benefits in 1908—the 100 principal unions accounted for 80% of total expenditure.24 If that ratio held throughout 1892–1910, then the average annual expenditure on unemployment benefits by all trade unions was £585,600.

The generosity and maximum duration of benefits differed substantially across unions. In 1892, the average weekly benefit was about 10s., at least for the first 12–14 weeks of unemployment. The benefit plans of the following four unions provide an idea of the range in generosity and duration. The Amalgamated Engineers paid an unemployed member 10s. per week for the first 14 weeks of unemployment, then 7s. per week for the next 30 weeks, and 6s. per week for another 60 weeks. An unemployed member could collect benefits for 104 consecutive weeks. The Amalgamated Carpenters and Joiners paid 10s. a week for the first 12 weeks of unemployment, then 6s. a week for the next 12 weeks. The maximum duration of benefits was 24 weeks. The London Society of Compositors paid an unemployed member 12s. per week for a maximum of 16 weeks in one calendar year. The Amalgamated Smiths and Strikers paid 6s. per week for a maximum of 8 weeks.25

Table 4.5 presents data on generosity and duration of unemployment benefits in 1908 for all trade unions and for unions in building, mining, metals, engineering and shipbuilding, and textiles. For all unions, the maximum weekly benefit was between 9s. 3d. and 10s. for 41% of workers, and 10s. 3d. or above for 20% of workers. On average, benefits in 1908 were about equal to their level in 1892. The maximum duration of benefits varied widely—it was 52 weeks or longer for 48% of workers in metals and 41% of miners, but only 19–25 weeks for the majority of workers in the building trades, and 13 weeks or less for the majority of textile workers. For trade unions as a whole, the median duration of benefits was 19–25 weeks.

TABLE 4.5. Unemployment Benefits Paid by Trade Unions, 1908 |

|||||

(A) MAXIMUM WEEKLY BENEFITS (PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF UNION MEMBERS) |

|||||

Weekly Benefits |

Building Trades (21 Unions) |

Mining and Quarrying (46 Unions) |

Metals, Engineering, and Shipbuilding (166 Unions) |

Textile Trades (212 Unions) |

All Trades (699 Unions) |

12s. 3d. and over |

0.0 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

13.2 |

11.4 |

10s. 3d. to 12s. |

0.1 |

9.4 |

2.3 |

4.5 |

8.7 |

9s. 3d. to 10s. |

70.8 |

60.5 |

50.4 |

17.9 |

41.2 |

8s. 3d. to 9s. |

25.6 |

20.2 |

9.3 |

14.0 |

13.6 |

7s. 3d. to 8s. |

0.1 |

0.7 |

5.8 |

10.3 |

4.5 |

5s. 3d. to 7s. |

0.7 |

0.3 |

1.2 |

20.3 |

6.2 |

5s. and under |

0.4 |

2.0 |

27.8 |

17.2 |

10.1 |

Not ascertainable |

2.2 |

7.0 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

4.2 |

Total Union Members |

95,077 |

392,542 |

293,666 |

310,499 |

1,473,593 |

(B) MAXIMUM DURATION OF BENEFITS (PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF UNION MEMBERS) |

|||||

Duration |

Building |

Mining |

Metals |

Textiles |

All Trades |

52 weeks or more |

0.0 |

41.0 |

48.4 |

1.2 |

21.9 |

39–51 weeks |

0.0 |

0.4 |

2.6 |

4.3 |

1.9 |

27–38 weeks |

0.0 |

9.0 |

7.9 |

3.4 |

4.8 |

26 weeks |

0.1 |

0.9 |

8.1 |

9.9 |

11.9 |

19–25 weeks |

57.7 |

3.1 |

7.8 |

9.3 |

12.1 |

14–18 weeks |

0.0 |

0.2 |

17.4 |

17.7 |

9.0 |

12–13 weeks |

3.0 |

8.9 |

3.0 |

16.3 |

11.9 |

7–11 weeks |

36.4 |

23.5 |

1.8 |

2.8 |

13.3 |

6 weeks or under |

0.7 |

6.1 |

1.2 |

33.3 |

9.6 |

Not ascertainable |

2.2 |

7.0 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

3.8 |

Total Union Members |

95,077 |

392,542 |

293,666 |

310,499 |

1,473,593 |

Source: Board of Trade, Report on Trade Unions in 1908–10 (1912), pp. lxxvi–lxxxi. |

|||||

How did benefits compare to wage rates? The average weekly wage for carpenters in 29 large cities was 34.2s. in 1892 and 38.6s. in 1908. The maximum replacement rate for carpenters was, on average, 29% in 1892 and 26% in 1908. For fitters, the maximum replacement rate was, on average, 30% in 1892 and 28% in 1908.26 These replacement rates were relatively small, and they declined over time. A member of the Amalgamated Engineers unemployed for more than 14 weeks in 1892 would see his replacement rate fall to 21%; if unemployed for more than 44 weeks, his replacement rate fell to 18%. Similarly, a member of the Amalgamated Carpenters and Joiners unemployed for more than 12 weeks would see his replacement rate fall to 18%; if unemployed for more than 24 weeks, his benefit fell to zero.

The weekly benefit was supposed to be enough to enable unemployed members to subsist without turning to charity or the Poor Law. In this, most trade unions appear to have been successful. Beveridge maintained that union members receiving unemployment benefits hardly ever applied to local distress committees. He added, however, that by itself the typical benefit was too small to provide subsistence for a worker and his family, and had “to be supplemented . . . by the earnings of wife and children, by private saving, by assistance from fellow-workmen and neighbours, by running into debt, by pawning and in other ways.” Nevertheless, union benefits prolonged “almost indefinitely the resisting power of the unemployed.”27

UNEMPLOYMENT RELIEF FOR LOW-SKILLED WORKERS

The Crusade Against Outrelief strove greatly to reduce, if not eliminate, the payment of outdoor relief to unemployed workers. It faced its first real test during the downturn of 1878–79. The Local Government Board and the Charity Organisation Society pressured local boards of guardians not to grant outdoor relief to the unemployed, and the COS also tried to block the indiscriminate use of charity. Their policies were especially successful in East London, where outdoor relief for the unemployed was virtually eliminated by the mid-1870s. Those who applied for poor relief during the downturn of the late 1870s were offered a place in the Poplar “test workhouse.” The COS also succeeded in keeping the Lord Mayor from starting a Mansion House Relief Fund, as had occurred in 1860–61 and 1866–67, although local unorganized charity must have increased.28

Outside of London, the policies of the LGB and the COS were less successful. Some Poor Law unions that had begun to shift to workhouse relief in the early 1870s felt compelled to provide outdoor relief to the unemployed in 1878–79.29 In those unions that resisted the temptation to provide outdoor relief, local governments and voluntary agencies adopted ad hoc measures for relieving the unemployed. The typical procedure was for a city’s mayor to set up an emergency fund whenever distress reached a certain level: “[The mayor] issued an appeal in the Press or by letter, the response to which in the form of donations was of course very uncertain, varying with his personal popularity as well as with the general opinion of the wealthier classes as to the existence of exceptional distress. . . . The distribution was usually undertaken by a committee formed either from a few people selected by the Mayor, or from the borough councilors, or from a public meeting to which representatives of charitable agencies and others were specifically invited.”30 During the winters of 1878–79 and 1885–86 emergency funds were initiated in several large cities. In 1878–79 the Manchester and Salford District Provident Society, a philanthropic organization “dominated by the elite of Manchester’s commercial and industrial bourgeoisie,” raised £26,000 for the “temporary relief of distressed operatives.” In the same year the Glasgow Unemployed Relief Fund raised over £33,000 to assist the unemployed, and relief funds were established in Liverpool, Leeds, and elsewhere.31 These emergence funds typically provided the type of indiscriminate relief that the COS strenuously opposed.

The provision of emergency funds for the unemployed was even more pronounced during the 1885–86 downturn. The largest, and most notorious, of these was London’s Mansion House Fund of 1886, established by the Lord Mayor in response to unemployed workers’ demands for assistance, despite the opposition of the COS. A “riot” in London’s West End shortly thereafter by 20,000 workers—mostly unemployed dockworkers and building laborers—led to a rapid influx of money, eventually reaching £78,600. The central committee administering the fund attempted at the outset to ensure that relief was given only to “respectable” workers who were temporarily unemployed, but most districts relaxed these rules almost instantly, granting assistance to applicants indiscriminately. R. Roberts, who distributed relief in Islington, testified before a Special Committee of the COS that “the tendency of the fund was to drift to the relief of the permanent poor. Do what we would to avoid it, we could not help the drifting.” When asked if any investigation was made into the character of applicants, he replied, “Yes . . . all were in distress, and that was considered sufficient ground” for relief. The result was an “orgie of relief” in which most of the assistance went to the chronically unemployed. The 1886 Mansion House Fund caused a “widespread revulsion” among the middle class against “indiscriminate almsgiving to the unemployed.”32

The story of the Mansion House Fund reveals a serious unintended consequence of the Crusade Against Outrelief—the decline of options for assistance available to unemployed low-skilled workers. Most workers felt a strong stigma against entering a workhouse, and the COS was unable, and unwilling, to relieve more than a small share of the unemployed. When levels of distress increased during downturns, the unemployed pressured local governments for aid. Feelings of compassion, guilt, and fear among the middle and upper classes led to the launching of emergency funds and the granting of indiscriminate relief. To many, the consequences of the Mansion House Fund’s lax administration were far worse than the consequences of outdoor poor relief had been. The crusade had succeeded in reducing the relief roles, but the downturn of 1885–86 showed that it was unable to cope with unemployment during cyclical downturns.

The experiences of 1878–79 and 1885–86 convinced many observers that government involvement was necessary to relieve the cyclically unemployed, and officials searched for a method that local governments could administer and finance without the stigma of the Poor Law. In March 1886 Joseph Chamberlain, President of the Local Government Board, issued a circular to boards of guardians stating that “there is evidence of much and increasing privation . . . in the ranks of those who do not ordinarily seek poor law relief,” and advising municipal authorities in districts where “exceptional distress prevailed” to set up work relief projects to employ workers who were “temporarily deprived of employment.” The work provided should “not involve the stigma of pauperism”; it should “not compete with that of other labourers at present in employment”; and it should “not [be] likely to interfere with resumption of regular employment in their own trades by those who seek it.” To ensure the employment of respectable workers, all “men employed should be engaged on the recommendation of the guardians as persons whom . . . it is undesirable to send to the workhouse, or to treat as subjects for pauper relief.” Finally, in order not to compete with private employment, “the wages paid should be something less than the wages ordinarily paid for similar work.”33

The LGB reissued the Chamberlain Circular in 1887, 1891, 1892, 1893, and 1895. An 1893 Board of Trade inquiry found that 96 local authorities had initiated some form of public employment in the winter of 1892–93 in response to the issuance of the circular; 33 of them were in London. The forms of work relief included road repairing, road sweeping, sewerage work, stone-breaking, snow removal, leveling land, and planting trees.34 Few local authorities offered full-time work to those who applied; rather, they dispersed the available work among all of the applicants. Each person typically was employed two or three days per week.

For example, from December 1892 through April 1893, the corporation of Leeds employed 1,103 men to excavate and level ground for new parks. Each person was employed three days a week; the average man was given about 60 days’ work. Wages were 5d. an hour for a 9-hour day, so that each worker was paid about 11.25s. per week. Similar projects were initiated in other years. In the winters of 1903–4 and 1904–5, the corporation of Leeds employed 2,644 and 2,384 men to work on parks and roads, paint, and lay out a cemetery. As before, each worker was employed three days a week, and paid 5d. per hour for a 9-hour day.35

The borough of West Ham, just east of London, initiated relief works during six of the ten winters from 1895–96 to 1904–5. From November 1904 to May 1905, the borough council employed 5,271 men to lay out and pave streets and to paint and clean buildings. In order to distribute the available work fairly, every applicant was offered two or three days’ work until all had been employed, at which point the first applicants were offered another two days’ work. The rate of pay was 7d. per hour, for an 8-hour day.36

Sometimes charities worked together with local authorities. In the winter of 1895 the lord provost of Glasgow initiated relief works breaking stones; an average of 1,036 men were employed per day for 36 days. The total cost of the project was £4,854. When the weather grew more severe, the lord provost, unwilling to raise taxes any further to provide work, set up a relief fund and appealed to the local newspapers for contributions to enable local authorities to “give food, fuel, and clothing to those who were suffering terribly.” Within eight days, the Citizens’ Relief Fund had received £9,586 in cash and £1,362 “worth of food, provisions, coals, and clothing.” Eleven soup kitchens were set up; coal, boots, and clothing were distributed to those in need; 22,669 grocery tickets were allocated; and rent arrears were paid.37

Similarly, in the winter of 1904–5 several London newspapers raised relief funds for West Ham. The Daily News raised £11,800, £7,000 of which was spent on work relief; the rest was used to purchase bread, groceries, and coal, which was distributed to the poor. The Daily Telegraph raised £14,835, much of which they gave to local clergy and the Salvation Army to distribute to the poor. Altogether, newspaper funds raised £27,900 for relief of the unemployed, slightly more than the amount spent on work relief by the borough council.38

In view of the fact that the relief works outlined in the Chamberlain Circular were supposed to employ workers “temporarily deprived of employment,” almost all of the projects undertaken between 1886 and 1905 must be deemed failures. The 1893 Board of Trade inquiry noted above reported data on the occupations of men registered for work relief in nine London districts and six provincial cities in 1892–93. In London three-quarters of those on the registers were general or “chronically irregular” laborers, while in Liverpool 62% of those registered were general laborers, carmen, stablemen, porters, or messengers and another 26% were unskilled laborers in the building trades. Finally, in Leeds, where work relief was set up in response to an “acute depression of the iron trades,” 23% of those registered were from the engineering and metal trades, whereas nearly 50% were general laborers.39

Relief work was meant to avoid the problems associated, in the minds of the middle class, with the granting of outdoor poor relief or indiscriminate charity to able-bodied males, but the work relief of 1886–1905 turned out to be similar in many ways to pre-1870 Poor Law relief. Both were financed out of local taxation. Despite the LGB’s urging that municipal relief works hire only the temporarily unemployed, they ended up employing mostly the low-skilled and those employed in seasonal and casual trades, the same type of workers who had previously turned to the Poor Law for assistance. Jackson and Pringle concluded from their study of work relief programs that “the best that the relief works have accomplished is to provide another—generally inconsiderable—odd job to honest men who have to live by odd jobs, because of the irregularity of so much of our industry. The man for whom they were designed is not known to have had work from them yet.”40

THE UNEMPLOYED WORKMEN ACT OF 1905

Public awareness of unemployment as a problem increased during the late 1880s. The reason for the change in public perception is not entirely clear, but the publication of Charles Booth’s study of poverty in London—the first volume of which appeared in 1889—and the increased agitation by the unemployed were probably instrumental. Socialist groups such as the Social Democratic Federation began to organize protest marches at times of high unemployment during the mid-1880s.41 Pressure for new government policies to deal with the unemployed declined during the prosperity of the late 1880s, but reappeared during the downturn of 1893–95. In response to the high level of distress in the winter of 1894–95, the government established the Select Committee on Distress from Want of Employment. Nothing of practical importance came from it, but it bought time for the government until the pressure for reform died down when the economy returned to normal in the late 1890s. When unemployment rates increased sharply in 1904–5, demand that the government intervene returned. Demonstrators in London, Liverpool, Manchester, and other major cities “demanded that great works should be carried out by the municipalities on which they should be employed.”42

In response to this pressure, Parliament in 1905 adopted the Unemployed Workmen Act, which established distress committees in all 29 metropolitan boroughs and in municipal boroughs and urban districts with populations exceeding 50,000.43 The act also provided for the formation of a Central (Unemployed) Body in London, to administer relief and coordinate the work of the metropolitan distress committees. The committees—comprising nominees chosen by the local boards of guardians, borough councils, and charitable organizations—were empowered to register applicants for relief and provide temporary employment to those “deserving” applicants who previously had been regularly employed, had resided in the locality for the previous 12 months, were “well-conducted and thrifty,” and had dependents. The work projects were to be of “actual and substantial utility,” and workers’ total remuneration was to be less than would be earned by unskilled laborers.44

The act enabled localities to levy a rate of 0.5d. in the pound for administrative expenses, which could be increased to 1d. with consent of the LGB. Money from the rates was not to be used for work relief—relief projects were to be funded exclusively from voluntary contributions. The act’s framers apparently believed that, once distress committees and the machinery for administering relief were in place, the charitable public would contribute generously to relief funds during times of distress. This system of financing relief worked smoothly at first. In November 1905, Queen Alexandra’s appeal to the public for funds drew nearly £154,000, of which £125,000 was distributed to distress committees throughout Britain and Ireland.45

Despite the success of the queen’s appeal in raising money, few in the government believed that such appeals could be repeated annually. In 1906 Parliament made a grant of £200,000 to local distress committees; similar grants were made in the four following years. The parliamentary grant was meant to supplement voluntary contributions, but instead it led to a sharp reduction in contributions. According to Harris, “the charitable public declined to subscribe voluntarily to a scheme for which they were being compulsorily taxed.”46 The grants also led many local authorities to stop levying the 0.5d. rate for administrative expenses. Evidence of the changing nature of relief-project funding is given in Table 4.6, which compares the sources for the receipts of distress committees in 1906–7, the first year of the parliamentary grant, and 1909–10. In 1909–10, the distress committees received £146,835 from the parliamentary grant, or £41,415 more than they had received in 1906–7. During the same period, income from local rates and voluntary contributions declined by £46,774. By 1909–10 the majority of funding for local work relief projects came from the Treasury rather than from local contributions and taxes, as the Unemployed Workmen Act had envisaged.

The act stated that distress committees were to investigate applicants for relief and to provide work for those “deserving” workers who were temporarily unemployed because of a dislocation of trade. However, the distress committees proved no better than previous relief committees at separating the temporarily unemployed from the chronically underemployed. In 1907–8 general or casual laborers composed 53.3% of all applicants for relief; another 19.4% of applicants were employed in the building trades. A large share of these men were unskilled laborers who were more or less casually employed.47

TABLE 4.6. Sources of Funds for Distress Committees, 1906–7 and 1909–10 |

||||

|

1906–7 |

1909–10 |

||

Source of Funds |

£ |

% |

£ |

% |

Parliamentary grant |

105,420 |

40.2 |

146,835 |

57.2 |

Local rates |

90,088 |

34.3 |

68,069 |

26.5 |

Voluntary contributions |

36,202 |

13.8 |

11,447 |

4.5 |

Other sources (including repayments for work done) |

30,759 |

11.7 |

30,463 |

11.9 |

Total receipts |

262,469 |

|

256,814 |

|

Sources: Board of Trade, Labour Gazette, vols. 15 and 18 (1907: 327; 1910: 370). Note: For 1906–7, voluntary contributions include donations from the Queen’s Unemployed Fund. |

||||

Reports of individual distress committees give a better idea of the composition of the applicants for relief. In 1905–6 the Manchester distress committee registered 1,532 applicants for work relief. Of these, 52% were general laborers, 13% were laborers in the building trades, and 11% were carmen, stablemen, porters, and messengers. Altogether, three-quarters of the applicants could be classified as general or casual laborers.48 The COS, analyzing the registration papers of 2,000 applicants in West Ham in 1905–6, determined that 55% were casual laborers, 12% were laborers in the building trades, and 3% were carmen. Only 12% of applicants were classified as skilled workers, and half of these were in the building trades and subject to irregular employment. In 1906–7, 64% of the applicants for work relief in West Ham were classified as casual laborers, and an additional 14% were classified as “chronically bad—industrially, privately, or both,” or physically or mentally incapable of regular work. Less than 2% of applicants were skilled and regular artisans.49 In sum, only a small share of those given work relief were in fact temporarily unemployed.

Like all previous attempts to assist the unemployed, the Unemployed Workmen Act accepted the principle of less eligibility; that is, workers on relief projects should earn less than regularly employed unskilled workers in order to preserve work incentives. Some distress committees achieved this objective by paying workers on relief projects hourly wages below those of unskilled workers. Others chose to pay “full trade union wage rates per hour” but employ workers for a reduced number of hours per day or for two to four days per week.50

The London Central (Unemployed) Body employed men on relief works for 43 hours per week at 6d. an hour, for a weekly income of 21.5s. For comparison, in 1907 building laborers in London were paid 7d. per hour for a 50 hour week in summer.51 Weekly hours typically were shorter in winter, when relief works were in operation. If the workweek was six hours shorter in winter than in summer—one hour shorter per day—a man employed on a relief project would earn 84% as much per week as a fully employed laborer in the building trades. In 1905 “preference men” and casual laborers at the London docks were paid 6d. per hour for an uncertain number of hours per week. The average weekly earnings of this group of dockworkers, who made up nearly a quarter of the workforce at the docks, was almost certainly less than that of men employed on relief works.52

Outside of central London, employment on relief projects was less continuous. The reports of local distress committees to the Board of Trade for February 1907 show that the average number of days worked by men employed on relief works varied from 21 in Leicester and Glasgow and 17 in Norwich to 11 in Bristol and 6.8 in Brighton. The average earnings for the month varied from 83.8s. in Leicester to 44.3s. in Bristol, 42.5s. in Glasgow, 34.1s. in Norwich, and 21.6s. in Brighton. The average daily wage of men on work relief projects was slightly higher than the estimated wage of unskilled laborers in the building trades in Bristol, and was 80% or more of building laborers’ wages in Brighton and Leicester, but less than 60% of laborers’ wages in Glasgow and Norwich. Despite the high daily wage rates for work relief jobs in some cities, the low number of days worked per week meant that such jobs clearly were not a substitute for full-time employment in the building trade. However, many building laborers did not work full-time in the winter months, and many other casual labor markets also experienced “seasonal slackness” in winter. Because laborers in these markets could alternate work relief with private sector employment, it is not surprising that the majority of applicants for work relief were general or casual laborers, or that the same men tended to reapply for work relief year after year.53

Contemporaries also maintained that local charity and work relief affected employers’ hiring practices, encouraging the system of hiring and firing workers at will that was adopted by employers of dock labor at the port of London. Many dockworkers were underemployed even in relatively prosperous times, and often were forced to apply for work relief or private charity during slack periods. Beveridge concluded that the municipal work relief “doled out winter after winter” and the “perennial stream of charity descending upon the riverside labourer” was “a great convenience to the industry which needs his occasional services and frequent attendance. It amounts to nothing more or less than a subsidy to a system of careless and demoralising employment.”54

Some historians maintain that the Unemployed Workmen Act “marked a decisive turning-point in national policy” because it accepted “a measure of national responsibility” for relieving the unemployed.55 Most contemporaries, however, viewed the act not as the beginning of state intervention in the labor market, but rather as the last in a long line of failed attempts to use municipal relief works to solve the unemployment problem. According to Beveridge, “The Act started as a carefully guarded experiment in dealing with a specific emergency—exceptional trade depression—by assistance outside the Poor Law. One by one all the guards and restrictions have been swept away, or have become forgotten. The assistance, for the most part, has been given neither out of the resources contemplated by the Act (voluntary subscriptions), nor to the persons contemplated by the Act (workmen temporarily and exceptionally distressed), nor in substantial accordance with the principles of the Act as interpreted by the Local Government Board (that assistance should be less eligible than independence).”56

For many, the Unemployed Workmen Act was merely a stopgap measure. The same pressure that led to its adoption led the Conservative Government in December 1905 to appoint the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress. Virtually everyone who testified before the Royal Commission was impressed with the existing trade union unemployment insurance schemes and was in favor of extending insurance to a larger share of the workforce, although many opposed the adoption of a state-administered program. Despite the opposition to an increased role for the state, Parliament in 1911 established a compulsory, state-run system of unemployment insurance in a limited number of industries. The findings of the Royal Commission and Parliament’s reasons for adopting compulsory unemployment insurance are discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

Unemployment was a major cause of economic insecurity for British workers throughout the nineteenth century. Industrialization led to periodic business cycle downturns, and the second half of the century witnessed an alarming growth in the number of chronically underemployed urban low-skilled laborers. For manual workers not eligible for unemployment benefits from a trade union, spells of unemployment longer than a few weeks led to financial distress, and forced many to turn to other sources—typically local government or charities—for income assistance.

The forms of public and private assistance for the unemployed changed substantially from the 1860s to 1911. The Crusade Against Outrelief of the 1870s led to a sharp decline in the role played by the Poor Law in assisting the unemployed. However, the policies favored by the crusade—a combination of self-help and private charity—broke down during the 1885–86 downturn, leading the LGB to encourage municipalities to set up work relief projects when unemployment was high to assist those temporarily out of work. Neither the voluntary municipal relief works nor the work relief projects undertaken as a result of the 1905 Unemployed Workmen Act were successful in assisting the temporarily unemployed—most of those employed on relief works were chronically underemployed laborers.

The public assistance for the unemployed provided under the various policies adopted after 1870 was less certain, and less generous, than that available before 1870. Parliament’s adoption in 1909–11 of a national system of labor exchanges and compulsory unemployment insurance was more of a repudiation of late nineteenth-century policies toward the unemployed than an extension of them.

1. Webb and Webb (1929: 633); Webb and Webb (1909b: 243); Beveridge (1909: 1).

2. See Parl. Papers, British and Foreign Trade and Industrial Conditions (1905, LXXXIV), pp. 79–98 and Feinstein (1972: 225–26). For a detailed discussion of the Board of Trade series and its shortcomings, see Boyer and Hatton (2002: 644–48).

3. Boyer and Hatton (2002: 648–57); Lee (1979).

4. Beveridge (1944: 332).

5. Boyer and Hatton (2002: 661).

6. Board of Trade, Labour Gazette, October 1895, p. 308; Boyer and Hatton (2002: 661).

7. MacKinnon (1986: 306–7, 330–34); Boyer and Hatton (2002: 654–56, 659–60). The unemployment rate was benchmarked at 5.0% in 1875.

8. Data on the number of vagrants on January 1 and July 1 of each year are from MacKinnon (1984: 118, 337), and from the Board of Trade, Seventeenth Abstract of Labour Statistics (1915: 332–33). For the construction of the vagrancy series, see Boyer and Hatton (2002: 655, 659). To turn the vagrancy series into an unemployment series, the unemployment rate was benchmarked at 5.0% in 1875.

9. MacKinnon (1984: 117). Beveridge (1909: 48–49) and Crowther (1981: 254) also concluded that unemployment was a cause of vagrancy.

10. The Majority Report of the Royal Poor Law Commission concluded in 1909 that while the “material condition” of most workers improved “during the last few decades,” that of “the lower grades of unskilled labourers . . . was worse than formerly.” Parl. Papers, Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress (1909, XXXVII), p. 361.

11. The average unemployment rate, including short time but excluding the unskilled, was 6.3%. See Boyer and Hatton (2002: 663). Thomas (1988: 123) calculated that in 1931 the unemployment rate for skilled and semiskilled manual workers was 12.0%, while that for unskilled manual workers was 21.5%, nearly 80% greater.

12. Dearle (1908: 66–81).

13. The Board of Trade memorandum was published in Parl. Papers, Royal Commission on the Poor Laws, Appendix Vol. IX, Unemployment (1910, XLIX), pp. 638–55. See also Poyntz (1912). On seasonality in U.S. labor markets, see Engerman and Goldin (1994).

14. Jones (1971: 52–66) estimated that in London in 1891 casual workers and their families totaled about 400,000 persons, or one-tenth of the population.

15. Booth (1892a: 532–33). Howarth and Wilson (1907: 185–254) give a detailed discussion of the labor market at the Victoria and Albert Docks. See also Beveridge (1909: 77–95).

16. Charity Organisation Society (1908: 34).

17. Beveridge (1909: 96–98); Dearle (1908: 82–102); Tressell ([1955] 2005: 385).

18. Webb and Webb (1897: 160–61); Harris (1972: 295).

19. Webb and Webb (1897: 160–61); Beveridge (1909: 227). A similar conclusion was reached by the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on Trades Unions. See Parl. Papers (1868–69, XXXI), p. xliii.

20. Data for 1893 are from the Board of Trade’s Seventh Annual Report on Trade Unions (1895). Data for 1906 are from Parl. Papers, Royal Commission on the Poor Laws, Appendix Vol. IX, Unemployment (1910, XLIX), pp. 614, 620–21. Data on total union membership and the adult male workforce in 1906 are from Bain and Price (1980: 37).

21. Parl. Papers, Royal Commission on the Poor Laws, Appendix Vol. IX, Unemployment (1910, XLIX), p. 613.

22. Boyer (1988: 324–28); Beveridge (1909: 220–21); Porter (1970).

23. Data on unions’ annual expenditures on unemployment benefits are from Wood (1900: 83–86).

24. In 1908 the 100 principal trade unions contained 61% of the total membership of all 1,058 trade unions. See Board of Trade, Report on Trade Unions in 1908–10 (1912: xxxviii, lxxv).

25. Parl. Papers, Royal Commission on Labour: Rules of Associations of Employers and of Employed (1892, XXXVI), pp. 31–32, 45–46, 84–85, 157–58.

26. Wage data for carpenters and fitters in 1892 are from an unpublished Board of Trade report on Rates of Wages and Hours of Labour in Various Industries (1908). Wage data for 1908 are from Board of Trade, Twelfth Abstract of Labour Statistics (1908: 40–42).

27. Beveridge (1909: 225).

28. Ryan (1985: 145–50); Jones (1971: 278).

29. On the use of outdoor relief in 1878–79, see, for example, Trainor (1993: 305–9).

30. Parl. Papers, Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress, Report . . . on the Effects of Employment or Assistance given to the “Unemployed” since 1886 (1909, XLIV), pp. 72–73.

31. Kidd (1984: 52, 54); Beveridge (1909: 66); Cage (1987: 92–95); Webb and Webb (1929: 640–41).

32. Charity Organisation Society (1886: 91); Beveridge (1909: 158–59); Jones (1971: 291–94, 298–300); Harris (1972: 111).

33. Parl. Papers, Sixteenth Annual Report of the Local Government Board, 1886–87 (1887, XXXVI), pp. 5–7.

34. Parl. Papers, Agencies and Methods for Dealing with the Unemployed (1893–94, LXXXII), p. 212.

35. Parl. Papers, Agencies and Methods for Dealing with the Unemployed (1893–94, LXXXII), pp. 222–28; Parl. Papers, Report . . . on the Effects of Employment or Assistance (1909, XLIV), p. 359.

36. Parl. Papers, Report . . . on the Effects of Employment or Assistance (1909, XLIV), pp. 541, 551.

37. Parl. Papers, Third Report from the Select Committee on Distress from Want of Employment (1895, IX), pp. 232–33, 515, 519–20.

38. Parl. Papers, Report . . . on the Effects of Employment or Assistance (1909, XLIV), pp. 108–9; Howarth and Wilson (1907: 346–48).

39. Parl. Papers, Agencies and Methods for Dealing with the Unemployed (1893–94, LXXXII), pp. 210–11.

40. Parl. Papers, Report . . . on the Effects of Employment or Assistance (1909, XLIV), p. 39.

41. Harris (1972: 6–101); Himmelfarb (1991: 40–53); Brown (1971).

42. The quotation is from the testimony of Walter Long, President of the Local Government Board, before the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws: Parl. Papers, Minutes of Evidence . . . of Witnesses Relating Chiefly to the Subject of Unemployment (1910, XLVIII), p. 59.

43. Boroughs and urban districts with populations between 10,000 and 50,000 could apply to the Local Government Board for permission to establish a distress committee. By 1909, 14 such districts had established committees.

44. The best discussions of the Unemployed Workmen Act are found in Beveridge (1909: 162–91) and Harris (1972: 157–210).

45. Slightly more than half of the money distributed, £65,900, went to the London and West Ham distress committees. The fund also gave £9,450 to assist migrants to Canada, and made grants to the Salvation Army, the Church Army, and other charitable agencies. Parl. Papers, Report . . . on the Effects of Employment or Assistance (1909, XLIV), pp. 82–83.

46. Harris (1972: 179).

47. Beveridge (1909: 168–69).

48. Data on the occupations of Manchester applicants for work relief were obtained from the Webb Local Government Collection in the British Library of Political and Economic Science, Part 2: The Poor Law, vol. 307.

49. Howarth and Wilson (1907: 370–72, 376).

50. Beveridge (1909: 187).

51. Webb and Webb (1909b: 138). Wage date are from the Board of Trade, Eleventh Abstract of Labour Statistics of the United Kingdom, 1905–06 (1907: 38–39).

52. Beveridge (1909: 89–94).

53. Work relief data from Board of Trade, Labour Gazette, vol. 15, March 1907, p. 67. Wage data from Board of Trade, Eleventh Abstract of Labour Statistics of the United Kingdom, 1905–06 (1907), pp. 38–39. Webb (1912: 312–93); Jones (1971); Howarth and Wilson (1907: 378).

54. Beveridge (1909: 109).

55. Bruce (1968: 188).

56. Beveridge (1909: 189).