So far we have focused on strategies that you can implement in single lessons. But we are well aware that teaching involves a lot more than simply planning and delivering one-off learning episodes. You have to think about designing longer schemes of work and extended topics. You have to engage with colleagues who might either be interested in or sceptical about what is going on in your classroom. You will need to be thinking about how to help your children’s parents and carers understand what you are up to, and how to win their support – especially if their child is a little disconcerted by being asked to take more responsibility for their learning. These final two points – engaging with colleagues, and engaging with parents – are what we turn the focus to later in this chapter.

You might find that the LPA way of teaching rubs up against established norms within the school, and may want to start talking to the senior leadership team about these broader aspects of whole-school culture and practice. Could broader systemic changes benefit the children? What about the length of lessons? Or the way in which the school expects reports to be written on the children’s progress? Or perhaps rethinking the remit of the student council? In this final chapter we round up some of these wider issues to do with becoming an LPA teacher.

Embedding the LPA More Deeply

As you become more comfortable with the tweaks and techniques of the LPA, you may want to explore deeper and more systematic ways of developing your children’s capacities as learners. There are several approaches to doing this.

First, you can think about how to involve the children directly in thinking about the long-term development of their learning muscles. You can have formative conversations with them, in small groups or individually, about their development as learners, and help them think about which learning muscles they need to work on. They may make comments like:

“I’ve made a lot of progress with my collaborating skills, but now I think I need to focus more on being thoughtful and methodical about planning my own learning, and preparing for any problems that might come up.”

“I’ve got better at concentrating on my work, but I don’t think I’m as imaginative in thinking up fresh ideas as I could be, so I need to remember to give myself ‘brain time’ before I dive into a painting or a piece of writing.”

In many LPA classrooms each child can tell you which learning muscles they are working on at any given moment, and why.

Being in charge of my learning makes me feel proud. I am in control. It’s up to me to challenge myself and if I’m not choosing work that challenges me, I won’t be learning. You know your own mind so you know how to challenge yourself.

Second, you can find ways of linking the learning muscles to your medium- and long-term planning. Take the time to think about the learning demands of an upcoming topic and ask yourself which learning muscle or muscles are going to be needed, and how you could design activities to give those muscles a good stretch. Or you might ponder whether the class as a whole has a tendency to be distractible, or disorganised, or weak in their ability to craft a detailed, logical explanation, and think about how you could harness the next few topics and themes to target the development of those capacities. Are there any thinking routines you could use as the children work their way through a topic in English or maths? If they tend to be less resilient and determined than you would like, how could you build in progressively harder levels of challenge? How could you make the activities deeper and more open-ended, so that the children really have to stretch themselves to make the grade? Could the children help you to diagnose the capacities which they think they need to develop? How could you involve the children more deeply in planning and designing the kinds of activities that would stretch their learning muscles in positive ways?

First, take a moment to explore these further questions about planning to develop learning power across a series of lessons.

Wondering

What learnish might be useful in these lessons? How can you weave learnish in throughout the lessons?

How will you build reflection and craftsmanship into these lessons? What could the children reflect on? When will they reflect? At the beginning of the lesson? The middle? The end? Are there times in the week when we could specifically focus on building the skill of reflection? Would it be appropriate for the children to reflect on improvement in their learning muscles whenever they see fit, or should this be at set points?

How can you enable the children to reflect on and strengthen their learning muscles over a series of lessons? Should we concentrate on one or two this term? Which ones would be most useful to the children? What do they have to say about this?

Which lessons would be most suited to independent or collaborative learning? Or a mixture of both? Could you open up a discussion with the children about which approach would work best and why?

How can you continuously cultivate a relish of challenge within these lessons?

Are these lessons meaningful, relevant, and inspiring to the children? Will they see the point?

Once you have reflected, if you co-plan with other teachers it could be a great opportunity to share your findings about the LPA and collaboratively plan to strengthen learning capacities within your year group or key stage.

Engaging Colleagues

Engaging Colleagues

![]() Use window displays, doors, and notice boards.

Use window displays, doors, and notice boards.

![]() Adapt your learning environment.

Adapt your learning environment.

![]() Reward the children for developing as learners.

Reward the children for developing as learners.

![]() Link with like-minded colleagues.

Link with like-minded colleagues.

![]() Mention your interest in the LPA to your year group team.

Mention your interest in the LPA to your year group team.

![]() Run an introductory workshop on the LPA.

Run an introductory workshop on the LPA.

![]() Talk openly to leaders about the impact you are seeing.

Talk openly to leaders about the impact you are seeing.

![]() Use the student council.

Use the student council.

![]() Prepare an assembly to develop learning powers.

Prepare an assembly to develop learning powers.

Dipping Your Toes In

Sharing the LPA can be a sticky issue. Some schools see teaching style as an inviolable expression of personality. They think that as long as you are getting good results and the children are safe and happy, it is nobody else’s business to tell you how to teach. So suggesting to a colleague that there might be an alternative way of doing things can be seen as an implied criticism, or at least an unwelcome intrusion. It does no good to come across as evangelical, and you risk putting people’s backs up. So, depending on the school climate, a softly, softly approach might be best, or, if your school seems open and up for it, you could start to share what you have been up to.

Whatever your situation, we’ve found that the best way to gain interest is to lead by example – start by making small changes in your own practice and the results will speak for themselves. Your colleagues will begin to notice changes in the way your children talk, think, behave, and learn, and many will be genuinely interested to find out more. Most teachers want the best for their children, and if they see yours being more adventurous, relishing difficult challenges, and talking in an impressively mature way about how – as well as what – they are learning, they will seek you out to find out what’s behind the change. Here are just a few ideas about how – when the time is right – you can begin to broadcast what you are doing, and hopefully engage and intrigue at least some of your colleagues.

Use window displays, doors, and notice boards

The displays and notice boards in and around your classroom are first and foremost for the children and their learning. But many other people will pass by and engage with your displays – parents and carers, teachers, learning support assistants, helpers, children from other classes, senior leaders, the head teacher, and so on – which makes them a great opportunity to share what’s going on in your classroom. Simple signs on the door can hook passers-by’s interest. At Nayland Primary School in Suffolk in the UK you will see signs saying things like, “Watch out! Active learners in here!” or “Attention! Learnatics at work!” Not only do signs create interesting discussions with the children, but other staff, and visiting parents and carers, might wonder what is going on and ask you what they are all about.

Adapt your learning environment

Other changes to the environment in your classroom will also send signals about your philosophy and pedagogy to visitors. They might be intrigued by the fact that the layout of the furniture seems to keep changing, and you will have a chance to explain how you are aiming to stretch your learners’ collaborating muscles by altering the size and composition of groups, or giving the children choices about the social arrangements for learning. If you have various drafts and works in progress on display, annotated with the children’s feedback and comments – instead of the usual selection of the children’s best work – it makes people wonder about the purpose behind this. If you have a board celebrating the mistake of the week –as detailed in Chapter 4 – some of your visitors might think that’s a good idea too, while others’ first reaction might be to think you are daft. Baiting your classroom walls and windows with visible signs that you are trying something different can be a non-threatening and subtle approach to sharing ideas with colleagues, rather than trying to convert them head-on.

Reward the children for developing as learners

Do your children sometimes go to the head teacher for praise when they’ve shown great learning? Do they sometimes stand up in assemblies to celebrate their best work? Start celebrating the children in your class not just for the finished product, but for how they have showcased their development as strong, resilient, collaborative learners. Again, the main reason for doing this is to build your children up as powerful learners and embed the LPA values in your classroom. However, by doing this publicly, in a place where colleagues have a chance to see what is happening, some will want to know more, and this can open up a positive dialogue about what you are up to.

Link with like-minded colleagues

As you start to get the message of the LPA out there, you might find a few colleagues begin to show a particularly strong interest in your approach. Connect with these people and see if they would like to develop ideas for LPA teaching with you. This will create a support network and give you people to bounce ideas off. Inspiration breeds inspiration. If you’re stuck, join Twitter – there’s a great community of enthusiastic LPA practitioners out there, just waiting to share their practice. (See the Resources section at the end of the book for some suggestions.)

Mention your interest in the LPA to your year group team

If you sense your fellow teachers could be open to the LPA, suggest that you could take a few minutes in an informal meeting – over a lunchtime sandwich, say – to share what you are doing and why. Tell them about some of the quick wins you have had with the LPA and talk about the effect it has had on your class as a whole and – this is often the most powerful – on individual children who your colleagues know. We haven’t come across many teachers who don’t want to develop skills like concentration, empathy, and resilience in their learners. Share your current area of focus – for example, developing resilience – and see if they are interested too.

Run an introductory workshop on the LPA

If your school is on board and supportive, see if you can find a time to share your experience of the LPA with the whole staff or those from your key stage – for example, in a staff meeting or as part of a professional development day. Link with ideas that colleagues might already be familiar with, such as growth mindset. Share a little of the research behind the LPA and talk about your own personal findings in relation to the children’s developing confidence. It can be powerful to share a few case studies of particular children. Short videos of the children articulating their learning and demonstrating the effect of the LPA can also have a profound impact.

Digging Deeper

As you go deeper with the LPA you might find that you begin to rub up against some structural issues which are embedded school practices – for example, the length of lessons, construction of the timetable, standard practices about marking or reporting, limited use of the student council, or attitudes towards professional development. These are not things that an individual teacher has control over; they are matters of school policy that are the consideration of the senior leadership team. We will tackle these issues from a school leader’s point of view in more depth in the fourth book of this series. Here, we will just make a few suggestions about how individual teachers might go about broaching such subjects with their line managers and senior leaders, and raise the profile of the LPA within the school.

Talk openly to leaders about the impact you are seeing

Leaders are interested in how to make the biggest impact on learners. Some of this impact can be captured in the form of hard data, while other aspects may be easy to feel but harder to measure. It is not hard to tell when a child you know well is becoming more confident when asking questions, or braver about tackling new challenges, but it can be difficult to quantify. However, it would be rare to find a leader or head teacher who isn’t interested in both kinds of measure. So, if you have data to show an impact on progress, share it.

For example, Becky found that her LPA teaching led many of her “lower attainers” to make accelerated progress, through coming to believe in themselves as learners, learning to relish challenge rather than feeling scared, and learning strategies to make them more resourceful in their learning. Discussion during progress meetings demonstrated the very clear impact that using the LPA was having on her learners. If you don’t have data to share yet, talking about the impact on individual children – particularly on shyer children or those with behavioural difficulties – can also raise interest. In fact, if the LPA is having the effect it should, leaders will notice these changes in behaviour before you tell them.

Use the student council

Depending on the school ethos, another possible way to raise questions about whole-school practices could be through the student council. You might see if it is possible to have a discussion about the remit of the council, to see if leaders and colleagues might consider broadening it to include feedback from the children about how the school could be an even better place for them to learn. You may have to push the children to go beyond the familiar but less helpful concerns of “comfier chairs”, “cleaner toilets”, “better vending machines”, or “less bullying” to think more deeply about what makes it easier or harder for them to learn. But soon their ideas will become more focused, and start to fall on increasingly receptive ears. You might find that this roundabout way of involving senior leaders in thinking about the more structural aspects of the school – and the ways in which they impinge on learning – works better than trying to tackle those issues head-on in a staff meeting.

Prepare an assembly to develop learning powers

Do you have the opportunity to deliver assemblies in your school? Why not plan one around resilience, learning from mistakes, or developing empathy? There are plenty of great resources to get you started. For example, you could show the children a video of an athlete, musician, or TV presenter with whom they are familiar, and talk about the great learning powers those people must possess in order to achieve what they have. Or you could read a passage from a book which opens up a discussion around empathy or learning from mistakes. You could ask them which characters in the Harry Potter series or The Hobbit – or whatever is currently grabbing their interest – show strengths in which learning muscles. Guy remembers an assembly a few years ago in which the children became very involved in discussing the learning strengths of the different characters in Finding Nemo.

You could run an assembly that really involves all the children and gets them thinking. Becky experienced an assembly like this at School 21 in London, led by Peter Hyman and fellow teachers. Attendees to the assembly were asked to consider a time when they had “used their voice” to have an impact. Everyone stood up, quietened their minds, and took some time to privately consider when they had used their voice in such a way. They then had to silently consider the sentence stem, “I want my voice to be …” After taking the time to consider this, they were asked to walk around the hall, quietly at first and without making eye contact. They then had to engage with others, first by making eye contact, then by smiling, then smiling and waving, and finally by whispering their sentence stem as they passed each other by. They played around with volume to explore the effect their voices could have, eventually building up to shouting. The children then formed groups of three and decided on roles; two told the story of how they had used their voice for impact and the third had to make a link between them. The assembly finished with the children seated in a large circle, pulling ideas together.

This assembly may be better suited to slightly older children, and would work better with a smaller group, perhaps a particular key stage or year group rather than the whole school. Remember also that the children at School 21 have spent years getting used to this kind of learning situation. You probably couldn’t expect them to do this successfully right at the beginning of the LPA journey. Nevertheless, it’s worth considering the impact such an assembly would have compared to the more traditional format of the children sitting in rows facing the front.

Wondering

Which format actively includes every member of the audience?

Which format actively builds the children’s confidence?

Which format gets the children reflecting on their life experience?

Which format is most inclusive?

Which format purposefully builds collaboration and oracy skills?

Engaging Parents and Carers

Engaging Parents and Carers

![]() Write letters home about learning powers.

Write letters home about learning powers.

![]() Use window space and notice boards to bring the LPA to life.

Use window space and notice boards to bring the LPA to life.

![]() Use learnish in parents’ meetings, letters home, and reports.

Use learnish in parents’ meetings, letters home, and reports.

![]() Make links with home.

Make links with home.

![]() Run a workshop for parents and carers about the LPA.

Run a workshop for parents and carers about the LPA.

Dipping Your Toes In

Overall, we have found the majority of parents and carers to be receptive to and supportive of the LPA. Once they understand that it aims to develop their children as learners as well as their ability to do well on the tests, they tend to get on board and wholeheartedly support what you are doing. However, to reach this level, you will need to find strategies to raise their understanding of the LPA and to help them see how it benefits their child’s learning. Here are some ideas that we have seen used to successfully include families in their child’s learning journey and deepen their understanding of the LPA.

Write letters home about learning powers

Do you send weekly newsletters or curriculum updates home? Why not start to include information about which learning powers you are developing with the children? Perhaps you have a weekly or termly focus? You could write a couple of lines about how and why you are developing certain learning dispositions, and even invite feedback about how these learning dispositions are being developed at home. This not only informs parents and carers about how and why the children are learning to become more independent learners, but also gives them an opportunity to continue developing and stretching those learning muscles at home. Why not involve the children? Could they write a letter home explaining how they have been stretching their learning muscles? Letters from the children often get much more attention than those written by their teacher!

Use window space and notice boards to bring the LPA to life

As we have mentioned, window displays, doors, and notice boards provide great opportunities to invite discussion, provoke, and engage with other adults within your school community. Parents and carers often spend time looking at what is on display in the classroom windows when they drop off and pick up children, which makes those windows the perfect space for sharing some of the things you are doing. Put up notices about how you are developing the LPA. Display photos of children showing particularly great persevering, noticing, or analysing skills, with a short description to explain why this is important. This is even more powerful if written in child-speak.

Drip feed key ideas that underpin the LPA – such as learning from mistakes and valuing effort – into the displays. Becky displayed a large cellophane “yet” in her window for a term, challenging parents to use the word with their children as often as they could when they said they couldn’t do something. Parents commented on what a positive difference it had made to family conversations around learning. Sometimes it’s the most simple ideas and changes that can have the most profound impact.

If you’re feeling brave, you might want to turn your classroom and the corridors that surround it into an exhibition to celebrate children’s learning at the end of a project or topic. Share the idea with the children – they could plan displays and think about how to communicate with their audience. For example, they could create brochures about the exhibits or write letters home, inviting families along. As part of the planning for and reflection on the project, challenge the children to discuss and comment on which learning muscles will be stretched at different times. On this page is a photo from St Bernard’s RC Primary School, where the children concluded their songbirds project with a museum exhibition.

Use learnish in parents’ meetings, letters home, and reports

When sharing the children’s learning with parents and carers, both formally and informally, begin to talk about their skills as learners as well as their academic progress and achievements. Celebrate the children’s successes and improvements in perseverance, attention to detail, concentration, and ability to work with others in a variety of contexts. For example, when discussing a child’s writing, talk about how they have not only improved their spelling or range of styles, but also their ability to notice and learn from their mistakes. Discuss how their child has not only learned their times tables and developed their addition and subtraction skills in maths, but has also grown their ability to stick with a problem for longer and find their own ways to get unstuck. In art, talk about how their child has developed the ability to critique and to learn from feedback.

Share your intention to develop their children as adept, lifelong learners, as well as helping them do well on the tests. We have found that parents and carers generally respond positively to the idea that their children are valued in terms of their development as learners as well as their academic progress – especially when they can see for themselves that their children are learning knowledge and skills that will equip them to learn for themselves and survive in the big wide world.

Ideally, you can keep feeding in this message throughout the year, but you might also feed back on children’s development as learners in end-of-year reports. Many schools now have a separate section in their reports for comments on “the child as a learner”, as well as sections in which children can report on their learning themselves. If your school reports don’t have a section like this, see if you can thread learnish in throughout the report.

West Thornton Academy have handed their report writing over to the children. They write the entire report and teachers add a short comment, responding to the children’s ideas and contributing further observations of their own.

Through effective coaching in how to write these reports, children:

Your child as a learner

Eddy shows many traits of a strong, independent learner. He is curious and interested in everything, often continuing his learning at home and coming up with fantastic questions in class. He is an active listener who contributes to classroom discussions and thinks carefully about what is being said.

Eddy is equally happy to learn independently and with friends. When collaborating, he listens to the ideas of others as well as offering his own. Throughout the year, he has become better at knowing when to take a step back and let others contribute.

When learning independently, Eddy often comes up with original ideas to extend and practise his learning, such as inventing a game to learn key words. He loves to share these ideas with friends as well as noticing and adopting great ideas from others.

Figure 10.1: Report Sample from Becky’s Classroom

Depending on the receptiveness of your school, you could also coach children to contribute to or run their own parent-carer consultations. Done well, this puts children in the driving seat of their learning and provides the perfect opportunity for children to stretch their reflection muscles as they plan ways to inform their parents or carers about their progress – for example, by sharing some of the big wins they have made recently. In schools where this has been effective, children are given time to curate the work they would like to share, using specific criteria. For example, they might like to find a piece of work which shows particular resilience or craftsmanship, or a piece which is a good example of when they have used their thinking skills well. The children need to be coached on how to present the information so that they don’t freeze when it comes to parents’ evening. The children at West Thornton Academy run their own parent-carer consultations. Since they have planned their school day to give the children complete ownership and responsibility for their learning, they have achieved remarkable outcomes. One EAL learner, independently and off his own bat, created a PowerPoint to present his learning to his teacher and parent. The presentation was in his home language and he translated it to his teacher as he went.

Digging Deeper

Once you’ve embedded the language of the LPA into your usual interactions with parents and carers, and hooked their interest in what you are doing, you might want to focus on actively involving them in the approach.

Make links with home

Many LPA schools have found their own smart ways to involve parents in developing learning muscles at home. In many schools, Reception and Key Stage 1 classes use puppets to demonstrate different learning dispositions. These puppets are often sent home with a diary so that the children can write about how the puppet has demonstrated use of that learning muscle in a different context. Children love the privilege of being allowed to take the class puppet home. It helps them to make links with how that learning muscle can be stretched outside the classroom and includes parents and carers by helping them understand how their children are developing as learners in school.

Remember Julian Swindale’s positive learning behaviours whiteboard from Chapter 3, on which he recorded examples of effective learning throughout the day? He has found a way of sharing this with parents by collaboratively making a class e-book at the end of each week. The children – with some nudging from Julian – choose some of their best learning moments to share. They upload a photo and write a short comment ready to share on a Friday afternoon. Parents and carers gather into the classroom, and Julian guides the children through the e-book and encourages them to talk about their learning. It’s a brilliant way to share and embed the classroom ethos, give the children a chance to purposefully reflect on their learning, and for parents and carers to see how to continue their children’s learning at home.

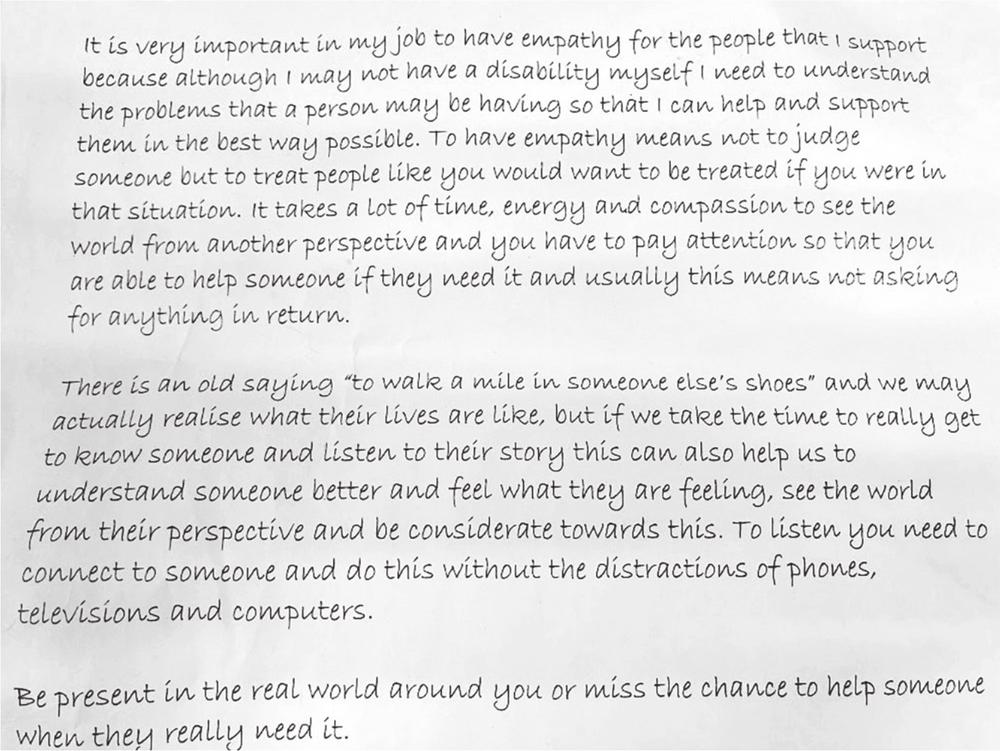

Each week at St John Fisher Catholic Primary School near Liverpool, the teachers introduce a new learning muscle during assembly. But they wondered how they could involve parents and carers in this process. They sent letters home asking them to write back explaining how they used learning muscles in their jobs. These letters were then shared with the children in assembly. Some of the letters were really powerful, such as the example pictured below, explaining how one parent uses empathy in her job.

Through this communication, everyone’s learning power grows stronger and deeper. The children can see how learning powers are essential in the adult world of work, and parents and carers gain a deeper understanding of the elements of the LPA. And those essential links are made between school and home.

Run a workshop for parents and carers about the LPA

Does your school ever run maths and English workshops to share strategies for developing these skills with families? Why not run a workshop on the LPA, or dedicate a slot at a parents’ evening to it? If you don’t have the opportunity to do this on a larger scale, or don’t feel confident about doing so yet, why not invite parents and carers into your classroom at the end of a school day? You could present some ideas, ask the children to talk about what they have been learning, share some photos of the children demonstrating using their learning powers, or bust some myths by explaining, for example, why making mistakes is such an essential part of learning. Taking the time to do this keeps everyone on board, gives the children the opportunity to share what’s been going on in the classroom, and enables caregivers to continue building on the children’s learning powers at home.

Wondering

Think about how your interactions with parents and carers currently go. Are they as positive and satisfying as you would like them to be? Though not all parents and carers are equally easy to get along with, can you think of a couple of small ways in which you might try to engage them in more productive and interesting conversations about their child as a learner?

Have a look at some reports you have written recently. Can you think of any ways in which you might have captured a more rounded picture of those children? Could you have said more about how they have changed over the course of a term or a year?

Could you spend time finding out more about the children’s learning lives out of school? How could you weave those little conversations into the school day?

Which of your colleagues do you think you could learn most from? Are there any opportunities for you to spend time in their classrooms just watching what they do – and how the children respond?

Bumps Along the Way

As usual, here are some thoughts from Becky about how you might cope when things don’t go quite according to plan.

Summary

There is only so much a single teacher can do to develop children’s learning power. They say it takes a village to raise a child, and if the LPA is to have maximum impact on children’s development, it ideally needs to be acknowledged and attended to by all members of their community: teachers, learning support assistants, parents, carers, and others. In this chapter we have assumed that you might be something of a lone wolf to begin with, and will need to work to get others on board. If that is the case, we hope that some of our ideas will be useful. However, if you are lucky, you will already be a member of a supportive and knowledgeable community of teachers who are only too willing to support you, and to learn with and from you, as you grow in confidence and experience. In this case, perhaps some of our ideas about how to strengthen your links with parents will be helpful. Or perhaps you will have some more ideas to share with other members of staff, who may be new to both your school and to the LPA, so you can invite them to join your growing pack.