APRIL 6–7, 1862

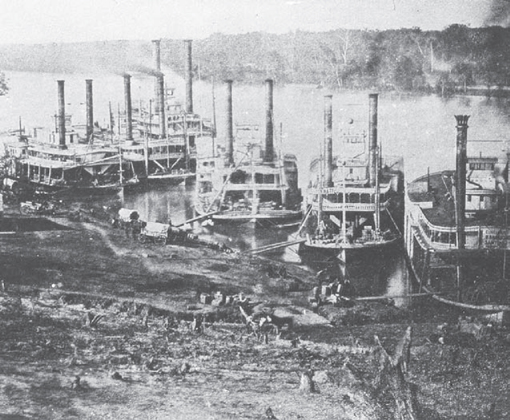

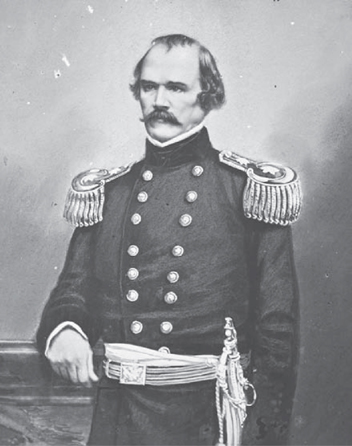

By the fall of 1861, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, the officer responsible for the defense of much of the Confederacy’s western regions—an area extending from the Cumberland Mountains to beyond the Mississippi River—faced a crisis of manpower. With fewer than 20,000 poorly armed and trained soldiers under his control, Johnston believed that he faced overwhelming Union pressure. He was acutely aware that the western Confederacy was divided by a series of great navigable rivers that provided ready-made lines of advance for his adversaries. The greatest was the Mississippi, already the target of Federal General in Chief Winfield Scott’s “Anaconda Plan,” a series of combined land and naval operations intended to encoil the South and strangle the seceding states. Other strategic rivers included the Cumberland, which flowed through north-central Tennessee before joining the Ohio, and the Tennessee, with its 200 miles of navigable waters reaching all the way down to northern Alabama. The Tennessee also emptied into the Ohio, not far from the mouth of the Cumberland.

To defend his western border, Johnston had 11,000 men under Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk blocking the Mississippi with fortifications on the river bluffs at Columbus, Kentucky. Johnston also dispatched Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner’s forces to Bowling Green, Kentucky, to guard the approaches by rail to Nashville and threaten the key Union position of Louisville. By the winter of 1861–62, Buckner had been superseded by Maj. Gen. William Hardee, and the Confederate force there increased to 22,000 men. Other forces were sent to cover access to Cumberland Gap, while earthwork fortifications, Forts Henry and Donelson, were constructed near the Kentucky line, where the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers were but 12 miles apart, to control the traffic on the water routes south.

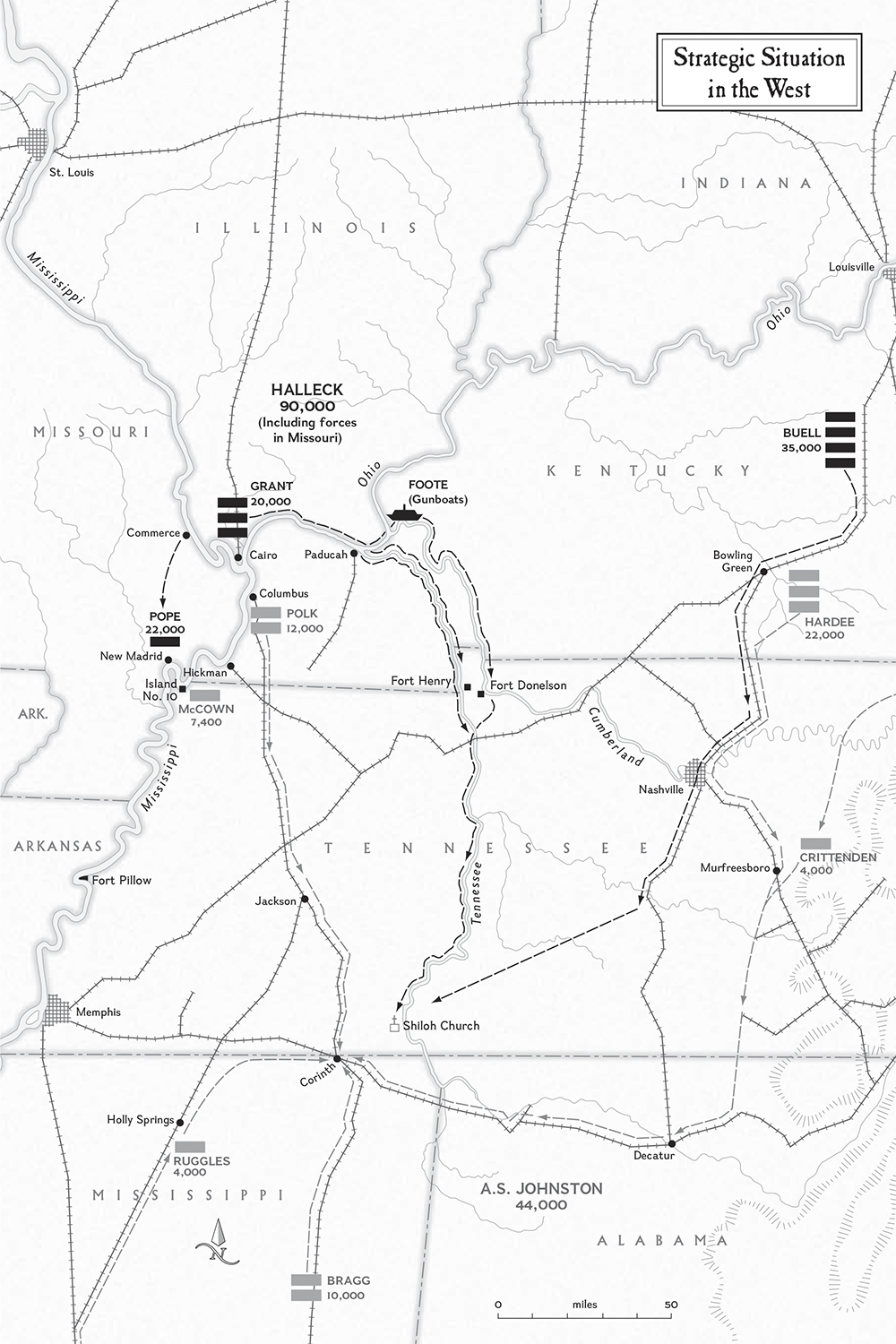

By late winter two Federal Armies, totaling perhaps 37,000 men, faced Johnston—the Department of the Missouri, headed by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck with his headquarters at St. Louis, and the Department of the Ohio, commanded by Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell. In mid-January the defeat of Confederate politician-general Felix Zollicoffer’s and West Pointer and Brig. Gen. George Crittenden’s combined forces at Mill Springs, Kentucky, resulted in the collapse of the right flank of Johnston’s 300-mile line. Belatedly Johnston sent orders to strengthen Forts Henry and Donelson, but he was far too late. The Federal Army commander at Cairo, Illinois, a quiet and scruffy-looking brigadier general named Ulysses S. Grant, had been made aware of the forts’ weaknesses and quickly made plans to capture them in preparation for a thrust deep into Tennessee. Grant’s forces were supported by a fleet of U.S. gunboats under the command of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote. In early February 1862, Grant ordered his men to board river steamboats, and the armada steamed up the Ohio toward the Confederate forts.

The river navy attacked first, with Foote’s gunboats pounding Fort Henry on February 6. The fort’s commander, Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, with many of his batteries flooded by high water, evacuated most of his garrison and remained behind with 90 men to face the Federal gunboats, four of them ironclads. After a sharp exchange of gunfire, Tilghman capitulated. Heavy rain delayed Grant’s investment of Fort Donelson until February 12. Hoping to buy time to evacuate troops from western Kentucky, Johnston reinforced Donelson, sending 12,000 men under Brigardier Generals John B. Floyd, Gideon J. Pillow, and Buckner to strengthen the fort, bringing the number of defenders to 17,000.

Despite the fact that he was now outnumbered, the ever aggressive Grant closed in on Fort Donelson’s outer defenses with two divisions under Brig. Gens. Charles F. Smith and John A. McClernand. On February 14 the Federal naval flotilla attacked the fort, only to be turned back by Rebel cannon emplaced in the fort’s water batteries. Despite their success in repelling the gunboats, Floyd, as senior officer and in command of the troops in Fort Donelson, launched a breakout attempt on the following morning. Although the Confederates broke through the Federal lines and secured a route of escape, determined counterattacks led by Federal Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace and Brig. Gen. C. F. Smith caused the Rebels to withdraw back into the fort’s perimeter. General Floyd and his second in command, General Pillow, escaped from the fort with most of the former’s men, leaving General Buckner to request terms of surrender from Grant. There would be no terms offered, replied Grant, only “unconditional surrender.” Nearly 13,000 Confederate soldiers were taken prisoner. Wags in the Union press and Army soon essayed that the general’s initials must now stand for “Unconditional Surrender.”

During the next fortnight Grant fended off an effort by a jealous Henry Halleck to replace him. Nearly four weeks later another force, under Union Maj. Gen. John Pope, captured New Madrid, Missouri, and then on April 8 Confederate Island No. 10, opening the Mississippi south to Fort Pillow, Tennessee. The back of Albert Sidney Johnston’s defensive line was broken, and the Confederate heartland opened to invasion. Abandoning Kentucky and much of middle and west Tennessee, Johnston withdrew his forces, abandoning Nashville as well. He reached Decatur, Alabama, by March 15. Polk had already withdrawn from Columbus, Kentucky, leaving the Mississippi north of Fort Pillow under Federal control.

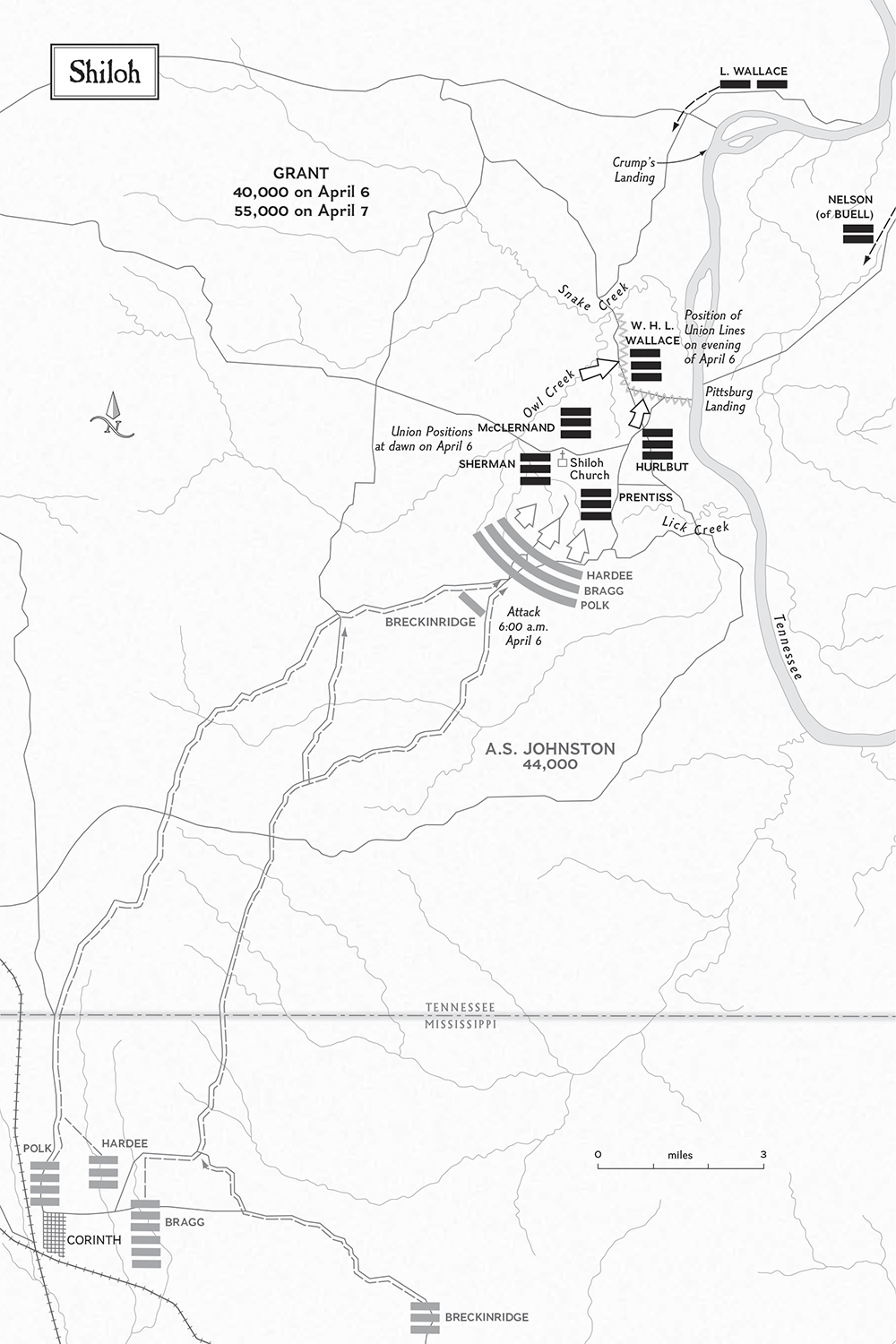

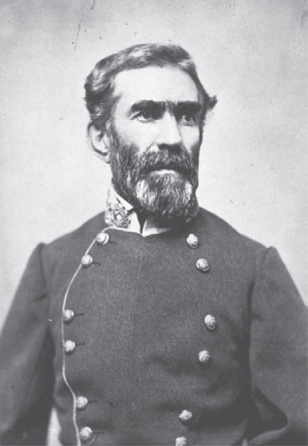

The Confederates began to regroup at Corinth, Mississippi, just south of the Mississippi/Tennessee line. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard had arrived in the western theater in early February, and Johnston had immediately assigned him the task of marshaling reinforcements from the Confederate forces in the lower South. Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles arrives from New Orleans with 5,000 men while Maj. Gen. Braxton Bragg comes north with more than 11,000 troops from Mobile, Alabama, and Pensacola, Florida. By March 24, Johnston and Beauregard have 44,000 men concentrated at and around Corinth.

Henry Halleck, the Federal commander, directs the armies of Grant and Buell to rendezvous at a rural steamboat fueling point along the west bank of the Tennessee River known as Pittsburg Landing, which is less than two dozen miles northeast of Corinth. By April 1, Grant had concentrated nearly 40,000 men around Pittsburg Landing, and on March 16, Buell began his slow, 120-mile overland march from Nashville. Once these forces were united, Halleck planned to take personal charge for an advance on Corinth. For the moment Grant was ordered to avoid a general engagement. Rather, he is to drill his new recruits and his Fort Donelson veterans, preparing for a forward movement.

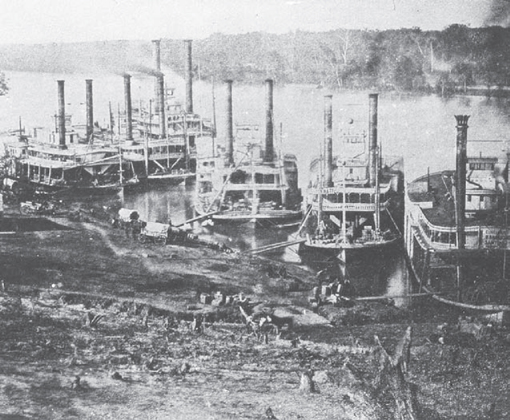

Union steamboats at Pittsburg Landing in 1862. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant arrived at the scene of the fighting at Shiloh aboard the Tigress, shown second from the right.

As the Union troops disembark at Pittsburg Landing they go into camp. William T. Sherman and John A. McClernand arrive. McClernand, now a major general, outranks Sherman, but Grant is a West Pointer. Sherman is also a West Pointer, and he is camped closer to the enemy, so Sherman is in command at Pittsburg Landing. There are five divisions at Pittsburg Landing—the First, under John A. McClernand; the Second, under Maj. Gen. C. F. Smith, who will be fatally injured by skinning his shin and developing a blood infection, and who will turn his command over to Brig. Gen. W. H. L. Wallace; the Third, under Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace; the Fourth, under Brig. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut; and the Fifth, under Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman. Lew Wallace’s Third Division is posted to the north, at Crump’s Landing on the west bank of the Tennessee. Grant locates his own headquarters on the east bank of the river at Savannah, Tennessee, eight miles downstream from Pittsburg Landing. He’s waiting there for Don Carlos Buell.

Last to arrive at Pittsburg Landing is the newly constituted Sixth Division. It is organized on the first day of April, and it will be commanded by a man Grant dislikes: Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss. Prentiss and Grant had previously feuded over rank. Rank is always important to soldiers, but particularly to general officers. Prentiss’s raw division includes a regiment that has seen combat, led by Col. Everett Peabody. Peabody, now a brigade commander, had been captured by the Rebels in the siege of Lexington, Missouri, the previous September. Prentiss’s people camp in a vulnerable position: They are between three of Sherman’s four brigades encamped around Shiloh Church, a tiny backcountry Methodist meetinghouse. Col. David Stuart’s brigade is posted way out on the Union left, on bluffs overlooking Lick Creek and the Tennessee River, to guard the road to Hamburg Landing.

The officers drill the men; the weather improves; the trees bloom. The Johnny-jump-ups come up and the peaches blossom. The soldiers get bored—a lot of these guys are homesick. They drill, but they do not entrench. Why don’t they? The prevailing tactical doctrine was crafted in the days of smoothbore muskets, which were notoriously inaccurate and with an effective range of 75 yards. Why entrench if the firepower is so weak? Shock and melee, the bayonet—those were the keys to infantry combat. More important, the Yankees establish Pittsburg Landing as their offensive base and think that if anyone’s going to be attacking, it will be them. They’re just passing time at Pittsburg Landing before they get the word to move out.

With the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson, Confederate General Johnston withdrew his forces into west Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and Alabama. In early March, Grant received orders to advance his Army of West Tennessee up the Tennessee River into the Confederate heartland. Grant moved to Pittsburg Landing to await the arrival of General Buell’s Army of the Ohio from Nashville. Once combined, both Federal Armies would advance and break the Memphis & Charleston Railroad at Corinth, Mississippi, to sever the Confederacy’s main rail communications between the Mississippi Valley and the East. Confederate Generals Beauregard and Johnston concentrated their forces at Corinth, hoping to strike at Grant at Pittsburg Landing before Buell could arrive.

A West Point error turned Hiram Ulysses into Ulysses Simpson Grant. Following his victories in the West at Forts Henry and Donelson, Grant earned the nickname “Unconditional Surrender”

Meanwhile, at Corinth, the Confederates create an army from disparate units. The Army of Central Kentucky is brought down by Generals Johnston and Hardee after it evacuates Bowling Green via Nashville. They’re also going to have a good part of Brig. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s force that had been beaten badly at Mill Springs, Kentucky, where they were led by Generals Crittenden and Zollicoffer. They’re joined by a large force led by Braxton Bragg, who arrives by rail from the Gulf Coast. Bragg’s soldiers may not love him, but they’re the Confederacy’s best drilled and organized troops. Stripping New Orleans of its garrison, Daniel Ruggles’s men come up from the Crescent City. Pierre G. T. Beauregard will bring down Bishop Leonidas Polk’s army, which had evacuated Columbus, Kentucky, following the loss of Fort Donelson. They create an army of 44,000 men in and about Corinth, and on April 3, on learning of the rapid approach of Buell’s army, the Confederates take the field. They plan to attack and best Grant’s army on Friday, April 4th, a most unrealistic schedule!

Sherman is in the habit of sending patrols down the Corinth Road. Out goes the 54th Ohio on April 3, and they see some people on the other side of a field, and then they go back. On the fourth the 72nd Ohio, another of Sherman’s regiments, and Maj. Elbridge Ricker’s battalion of the 5th Ohio Cavalry again go out the Corinth Road and clash with the vanguard of Hardee’s corps near Mickey’s. Sherman is beside himself: He had explicitly told his subordinates not to bring on an engagement. Also, Sherman is going to have a visitor that evening. Ulysses S. Grant is in the habit of undocking his headquarters boat, going eight miles upriver, and visiting the camps. They talk over the situation, and Sherman convinces Grant that the enemy is still at Corinth. Grant has bad luck. It’s raining—muddy. En route back to the landing, his horse falls, and it falls hard. It doesn’t break Grant’s ankle—it’s bruised badly and swells up. The next day Grant doesn’t come up—his leg is hurting him. In fact he is going to fight the Battle of Shiloh on crutches. He stays at Savannah on April 5 when Buell’s vanguard, the Fourth Division, under Brig. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson, arrives late in the day and goes into camp.

The Confederates, having closed to within several miles of Shiloh Church, have all day April 5 to finalize their attack plan. They won’t be interrupted by any more Union patrols. The Fifth Ohio Cavalry has been covering the army’s right, the Fourth Illinois Cavalry the army’s left, and they pick that day to reorganize and change their missions. Consequently, no mounted patrols go out on Saturday, and the one infantry regiment that goes out feels its way in the wrong direction—to the northwest—to encounter any Rebels.

The Federal camps, clustered to the south and southwest of Pittsburg Landing, are bounded on the east by the Tennessee River, to their west by Owl Creek, with a tributary, Shiloh Branch, to the southwest. Several smaller creeks, draining eastward into Lick Creek, form a series of deep ravines to the south. Three of Sherman’s four brigades are camped on a plateau fronting Shiloh Branch. But one of his regiments is camped in Rhea’s Field and separated from the others by a ravine. This unit is the 53rd Ohio, commanded by Jesse Appler, and several hundred yards separate these men from the camps of their comrades, the other two regiments of Jesse Hildebrand’s brigade. Soldiers of the 53rd Ohio see Rebels out there, but no one at headquarters believes them. Sherman, frustrated by Appler’s reports of Confederate activity, tells him to “take your damn regiment and go back to Ohio!”

What is Sherman’s mind-set with all of these activities going on? He knew the Confederates were out there. He knew there were cavalry and infantry units, but he believed that those Confederates out in the woods were merely scouts trying to detect when the Federal advance on Corinth would occur. He was thinking that he’d do the attacking. He also knew that he commanded inexperienced personnel. He kept telling everybody that these were volunteer officers, from civil life, and that they didn’t really have the experience and background that he had as a West Pointer and Regular Army officer. These men had as much idea of fighting a war as children, he said, and he used that terminology to demonstrate that the way of doing things in the Regular Army was that you discipline your men. You don’t go off half-cocked if you see Confederates lurking in the woods. You don’t think that you will be attacked—you’re not going to be an alarmist.

Grant shared Sherman’s perspective and trusted his reports. Aware that many of his men were raw recruits, he preferred to see them drilled to having them throw up field fortifications. He also believed that it would be up to the Union forces to bring on a battle by advancing against Corinth. Johnston and Beauregard had different ideas.

Beauregard draws up the attack plan. He knows that if the Confederates are going to win the battle, and the war, it must be a battle of annihilation. His goal is to crush the Yankees with succeeding waves of infantry, seize Pittsburg Landing, and drive the enemy into the river. In theory, if you are going to do that, you would mass your strength on your right, instead of forming your men in tandem. As at Manassas, Beauregard’s thinking is Napoleonic. He plans to deploy the Confederates across a broad front, like the French emperor had done at Austerlitz and Waterloo. Now, we all know who won at Waterloo, and it wasn’t the French. Advancing on a broad front might be good tactics in the open fields and sweeping vistas of Waterloo or Austerlitz, but the ground around Pittsburg Landing is broken up by woods and small farm fields, so the men cannot move together at the same speed. Indeed, the day had dawned bright and sunny and some of the Rebel staffers confidently called out “it’s another sun of Austerlitz.” But there the terrain and ground cover differed. When men advancing elbow to elbow come to an open field, they’re going to speed up, while soldiers to the right and left of them are working their way through the woods. When you attack on a broad front, as Napoleon observed, “a general who is strong everywhere, is weak everywhere.” Beauregard should have remembered this.

The Confederates form by corps in successive battle lines. William Hardee’s men are in front; he has four brigades, three of his and one of Braxton Bragg’s. He’s followed by Bragg, with five brigades; Polk, with four brigades; then Breckinridge, with three brigades. But it’s not clear who’s in charge. In April 1862 Beauregard was still revered as the hero of Sumter and Manassas. Although he’d had difficulties with President Davis, Beauregard was looked at as one of the premier generals of the Confederacy. Albert Sidney Johnston, on the other hand, had taken a lot of criticism for the loss of Forts Henry and Donelson, the Kentucky frontier, and much of middle Tennessee. Although he was the ranking officer, he decided to give Beauregard too much authority in terms of running the show. After all, Beauregard had been in the area for weeks, and he was a hero.

But on April 5, the eve of battle, because of the skirmishes that had occurred, Beauregard has second thoughts. “The Union camps have to be alerted,” he worries. “It took us three days to execute a march that should have taken us one; we’re not going to be able to surprise these Yankees and beat them.” Nervously he advises Johnston, “the Yankees are going to be entrenched to their eyes; we’re not going to surprise them. I think we better march back to Corinth without doing battle.” Johnston is shocked. Here’s a man he’s been relying on all these days to enact a bold strategy, to do something to win back the Mississippi Valley, and, on the very eve of attacking the enemy, Beauregard is losing his will. What kind of general is this?

As the two senior generals confer, the others listen. Again Beauregard expresses a reluctance to fight the battle. It is my opinion that at this time, Johnston decides he isn’t going to put a lot of reliance in Beauregard. In Johnston’s eyes he had displayed a surprising lack of will. Disappointed, Johnston leaves Beauregard as second in command, but places him in the rear echelon, with the task of pushing troops forward. That’s not a responsible role for the man you’ve been relying on to plan the operation. So Beauregard at the very last minute is given a minor role, as a result of his reluctance to go ahead with the attack plan he’d been responsible for developing.

The Confederate advance beginning on April 3 proved to be poorly planned and coordinated, filled with traffic jams. What should have been a day-and-a-half march turns into a three-day march, complicated by capricious spring weather—it can be 66 degrees one day, and 40 the next. It turns cold and rainy and dark. What happens when soldiers get cold? They eat more food. They consume all their rations. To make matters worse, nothing the field commanders can do can make the troops move quietly. They cheer and sound bugles, shoot at deer and rabbits, and one regiment even advances with its band playing. The generals debate whether to continue. Finally Johnston speaks. He’s willing to place his trust, as he says, on “the iron dice of battle.” And he says, “I would fight them if they were a million.”

It is an army of hungry, wet, irritable, and sometimes confused Confederates that finally arrives at the fringes of Grant’s encampment late on April 5 and early on April 6. As they deploy for their attack Union pickets continue to sense something is wrong.

Out on patrol is Capt. Gilbert Johnson of the 12th Michigan. He is cognizant of Rebels out there in the woods, and he reports that fact to his commanding officer, William Graves. Graves goes up the chain of command to brigade commander Col. Everett Peabody, 245 pounds, more than six feet tall, who had left Massachusetts to work as chief engineer on the Mississippi & Ohio Railroad. He was living in St. Joseph, Missouri, at the outbreak of the Civil War. Peabody decides to send out a combat patrol. Maj. James Powell, who has Regular Army experience, takes three companies of his regiment, the 25th Missouri, picks up another two companies of the 12th Missouri, and begins to probe into the woods. At 4:55 a.m., as they enter Fraley Field, they come under fire. A Yankee officer gets the privilege of being the first casualty. They exchange shots with the Confederates for about an hour—that means it’s now six o’clock. The firing ends, and there are casualties. Powell has lost about 30 men.

Peabody, on his own initiative, sends more men forward to find out what’s going on. By the time they arrive, the Confederates are coming. Yet the Rebel generals still waver. Johnston stands firm. The order goes out to advance, and Johnston swings into the saddle of his bay gelding, Fire-Eater, remarking, “Tonight we will water our horses in the Tennessee River.”

General Hardee sends the brigade of Col. Robert G. Shaver forward to deal with Peabody. The Confederates are coming in line, elbow to elbow behind Maj. Aaron B. Hardcastle’s Mississippians who formed the skirmish line for Hardee’s corps. Close behind Hardcastle’s boys are Shaver’s Arkansans and to Shaver’s right you have Brig. Gen. Adley Gladden’s people; Brig. Gen. S. A. M. Wood’s men and then Brig. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s brigade is on Shaver’s left. Powell’s bluecoats fall back. Shiloh’s earliest hero is Everett Peabody. Peabody mounts up and rides off to his death. His brigade will be virtually destroyed trying to hold up the Rebel advance.

Sherman’s people are still getting up, the cooks brewing coffee, the men getting ready for Sunday inspection. The firing in front of Prentiss has been going on for more than an hour. Peabody’s brigade battles Shaver’s men and initially stops them in their tracks. On Shaver’s right is Gladden’s brigade. Born in South Carolina, Adley Gladden is a veteran of the Mexican War, and a Louisianan by choice. His brigade strikes Madison Miller’s brigade of Prentiss’s division, and that fighting continues until about 8:30 a.m. By then, Gladden has been mortally wounded, and command passes to Daniel Adams. Peabody has been struck four times. This big man sits on his horse, bleeding, as he rallies his men for one last stand. He is hit again. The bullet strikes him below the nose and above the upper lip and drives into his brain. He’s dead when he hits the ground.

The 15th Michigan had just arrived at the landing; it has not even been issued ammunition. As they march out somebody says, “Was that shooting ahead?” Other soldiers reply, “I presume they’re shooting at squirrels.” And then as they get closer to the front they see many Sunshine Soldiers. Sunshine Soldiers are those four or five healthy men that seem to be needed to help a wounded man to the rear. It’s not pleasant to see men badly wounded. And the Michiganders remark, “those squirrels bite.” After briefly being engaged, the 15th Michigan is marched back to the landing, issued ammunition, and they’ll participate in the afternoon’s fighting.

Now the Confederates begin to forge ahead. They drive relentlessly forward as Bragg’s corps comes up, as do Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers’s five Mississippi regiments and one Tennessee regiment, and Brig. Gen. John K. Jackson’s brigade. They attack northeastward on either side of the Eastern Corinth Road. They drive Prentiss’s men from their camp a little before nine o’clock. Many of the Yanks will not stop running until they get back to the landing. Others halt and re-form.

General Johnston arrives amid Prentiss’s abandoned camps at this point. He has ordered his men to “Move forward and fire low.” They always admonish you to “fire low” because of the optics of the eye. Also, if you fire low, that means you’re going to hit the foe in the lower extremities, where if you wound a man it’s more of a problem. He also orders, “Do not halt! Do not plunder the camps. If men break and flee to the rear, they’re to be shot. You’re to keep up the momentum!” The Rebels are hungry. Most have eaten their three days’ rations. They arrive in the Yankee camps just as the Federal cooks are preparing breakfast, so they begin to plunder. Johnston picks up a small tin cup, and announces, “This is what I am taking; it will be my share of the spoils.” He will use this cup and not his sword throughout the day to direct his men. He also does something that may well cost him his life. He calls for his chief surgeon, Dr. David W. Yandell, and tells him, “You take care of these wounded, whether they’re Union or Confederate.” Dr. Yandell will not be with Johnston at a crucial time between 2 and 2:30 that afternoon.

Capt. Samuel H. Lockett is a senior engineer from Alabama, second in his West Point class of 1859. While out reconnoitering he sees a Union force near the river, which he estimates to be a division. Actually, it’s David Stuart’s brigade, detached from Sherman’s division. Looking to protect his flank, Johnston orders two brigades to attack Stuart.

Near Noah Cantrell’s house, one of the few frame buildings in the area, are David Stuart’s camps. Stuart is two miles as the crow flies from Sherman’s Shiloh Church headquarters. By 9 a.m., as we’ve seen, Prentiss’s division has been routed and driven out of its camps. Stuart can hear the firing. Stuart is very nervous. He’s isolated out here. The nearest friendly troops are Stephen A. Hurlbut’s division, back in Cloud’s Field, a mile and a quarter north. Stuart forms his three regiments in their camps on their respective color lines. Not knowing when or where the Rebels will appear, he moves from place to place. Stuart shifts his regiments about willy-nilly. Wonderful that he does this. He’s going to get a bonus. Captain Lockett, seeing these movements, makes a bad decision, and when he goes back to Johnston he reports that Stuart has a division of troops rather than a brigade. That’s when Johnston makes a fatal move. He sends two brigades, James Chalmers’s and John K. Jackson’s, to cope with Stuart. Much time will be lost, and by the time Chalmers and Jackson engage Stuart, it’s noon. Think of all the time the Confederates would have gained if they’d used these two brigades to follow Prentiss’s men as they retreated and re-formed in the thickets that bordered the “Sunken Road” that connects the Corinth-Pittsburg Landing and Hamburg-Savannah roads.

Sherman has camped three brigades around Shiloh Church; from left to right the brigades are commanded by Col. Jesse Hildebrand, Col. Ralph Buckland, and Col. John McDowell. Isolated in Rhea’s Field in their front is Col. Jesse Appler’s 53rd Ohio. He is in position to get in lots of trouble. In Sherman’s camps his people hear the sounds of the opening engagement. Back at Sherman’s headquarters, no one is alarmed. They figure it’s a continuation of the shooting and skirmishing they heard the previous day. Finally, about 7 a.m., Appler gets very nervous. He alerts Sherman that the Rebels are coming. Sherman patronizingly remarks, “It’s just one of Jesse’s scares.”

At dawn on April 6, Johnston’s army deployed just to the south of two of Grant’s camps. Despite resistance by some Federal units, the Confederates achieved almost total surprise. By mid-morning the Confederates had smashed one Federal division but faced fierce resistance on the Federal right near Shiloh Church. The Confederate attack on the right, near the Tennessee River, stalled in the dense thickets of the Hornets’ Nest before finally driving back Grant’s left in the late afternoon. Grant’s final line at Pittsburg Landing turned back the last Confederate charge at dusk. After nightfall Buell’s army moved into line on the Union left. On the following morning Grant launched a massive attack that drove back the exhausted Rebels, and Beauregard ordered a retreat.

Suddenly the Rebels emerge from the woods, led by Patrick Cleburne; they struggle to get through a morass formed by low ground along Shiloh Branch. As they do, Sherman rides up. Out there in the distance, at the far end of Rhea’s Field, he sees Confederates. They belong to S. A. M. Wood’s brigade. Sherman puts his telescope to his eye and looks off in that direction. Yankees now come out of the woods in his front shouting, “The Rebels out here are as thick as fleas on a dog’s back.”

Sherman then hears a shot, and Pvt. Thomas D. Holliday, his orderly, falls. Sherman throws up his right hand and drops his telescope; he gets a buckshot in his hand.

He rides back to alert his brigade commanders that the enemy is advancing.

The Confederates have a tough time. Col. J. J. Thornton is wounded and his Sixth Mississippi suffered many casualties, more than 70 percent (the fourth highest of any Southern regiment in a single battle), as it sought to fight its way across Rhea’s Field. The 23rd Tennessee, another of Cleburne’s regiments, breaks. Cleburne is thrown from his horse as he seeks to cross the “almost impassible morass.” Before being deserted by Colonel Appler and a number of their fainthearted comrades, the 53rd Ohio puts up a good fight—not as feeble as many writers report. But eventually they’ll be dislodged. Before they finally gain the upper hand on Sherman, the Confederates have to call for reinforcements to bolster Cleburne’s brigade. The Yankees shoot the daylights out of the 2nd Tennessee in its stand-up fight against the 72nd Ohio of Buckland’s brigade. Brig. Gen. Patton Anderson’s brigade of Bragg’s corps and Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson’s brigade of Polk’s corps join the action. Still Sherman’s men hold fast. Sherman may have been naive, but he is magnificent now. Inspired by Sherman, his men hold the Shiloh Church Ridge till 9 a.m. Finally, the Confederates commit another brigade, and at last Sherman’s men melt away.

Shortly after the Shiloh campaign the controversial Braxton Bragg was promoted to full general, eventually relieving P. G. T. Beauregard, who suffered from ill health.

Hearing the noise of battle, Grant, at 7:30, leaves his headquarters at Savannah’s Cherry Mansion, boards his headquarters boat, Tigress, and heads south toward Pittsburg Landing. He also sends orders to the head of Buell’s column to hurry up. But there are no steamboats on hand to move Buell’s troops; Brig. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson will eventually make his way by foot to a point across the Tennessee from Pittsburg Landing. Passing Crump’s Landing, Grant tells Gen. Lew Wallace to “have your men ready to march at a moment’s notice, in any direction to which it might be ordered.” It will take some time for him to bring his three brigades together.

Grant arrives at Pittsburg Landing at 9 a.m. He rides out to Sherman’s headquarters. Then he’ll ride from headquarters to headquarters before returning to the landing.

Union Maj. Gen. John McClernand has three brigades. They are camped in the area north and east of the intersection of the Corinth and Purdy-Hamburg Landing roads. The brigades are commanded by Col. Julius Raith on the left, Col. C. Carroll Marsh in the center, and Col. Abraham C. Hare on the right. On McClernand’s right are Sherman’s people—badly intermixed—as they fall back to re-form along the Purdy Road.

The Confederates smell blood. They bring up their artillery. Sherman feels fairly confident about his command as they pull back. A Confederate shell, however, is on target as cannoneers of the Sixth Indiana Artillery unlimber their six guns. Capt. Frederick Behr is gunned down, his battery panics, and there is chaos as teams and vehicles bolt through Sherman’s infantry, disrupting it. The Confederates bring the full weight of their attack on McClernand, and his division pulls back. Beauregard then makes an important command decision. He decides to coordinate operations from Sherman’s former headquarters at Shiloh Church. Johnston will remain at the front and inspire the men.

Stephen Hurlbut has three brigades in his Fourth Division, commanded by Col. Nelson G. Williams, Col. Jacob G. Lauman, and Col. James C. Veatch. When called to the front, the first two take position facing south, anchoring their left along the southern edge of a cotton field, with their right strung out along the “Sunken Road.” In truth the road is not truly sunken. They are soon joined by three brigades from W. H. L. Wallace’s division—two, one-armed Tom Sweeny’s and James Tuttle’s, take position on Hurlbut’s right, and the third, led by Brig. Gen. John McArthur, takes position on Hurlbut’s left, south of the Savannah-Hamburg Road. Holding the position between Wallace’s men on the right and Hurlbut’s people on the left are about a thousand men, all that remains of Prentiss’s division. You end up with about 11,000 Yankees along this one-mile front, soon to become known as the “Hornets’ Nest,” supported by 34 cannon. They are first tested when one of Polk’s Confederate brigades under Col. William H. Stephens appears. It numbers approximately 1,200 men. The Yankees soon lose six of their cannon when the 13th Ohio Battery, Capt. John B. Myers commanding, panics after a limber explodes, and the battery heads for Pittsburg Landing, leaving their six cannon abandoned out in Sarah Bell’s cotton field.

General Bragg hurls Stephens’s brigade across Duncan Field several times, against troops in a good defensive position with lots of artillery. Next on the scene for the Confederates is Col. Randall Lee Gibson’s Louisiana Brigade. Like Stephens’s they have no artillery support. Bragg sends Gibson’s brigade through the woods and underbrush, not once, not twice, not three times, but four times—to death and destruction. Bragg gets upset about the failure to break the Federal position, and he refers to Gibson as an “errant coward.” The brigade’s final charge is led by Col. Henry Watkins Allen, of the Fourth Louisiana, who has been shot through both cheeks. The bullet went in one cheek and out the other. Fortunately he had his mouth open when shot, but he’s bleeding badly. Bragg snaps, “I want no faltering now, Colonel Allen.” Allen’s men go forward to another repulse. By 3 p.m. there have been six Confederate attacks against the Hornets’ Nest, each ending in a bloody repulse.

By now the Confederate efforts to envelop the Union left anchored on either side of the Savannah-Hamburg Landing Road give promise of success. David Stuart’s bluecoats, assailed by Chalmers and John K. Jackson, abandon their positions at Noah Cantrell’s house and retreat northward across a west-east ravine and into the rugged ground beyond. General Breckinridge comes up with the brigades of Brig. Gen. John S. Bowen and Col. Winfield S. Statham, constituting two-thirds of the Confederate reserve. General Johnston and key members of his staff are there to provide inspiration and leadership. The Confederates’ goal is to overwhelm the three Union brigades (McArthur’s, Williams’s now led by Col. Isaac Pugh, and Lauman’s) holding the left of the Sunken Road line and hopefully to seize Pittsburg Landing.

The governor of Tennessee, Isham Harris, who is serving as a volunteer aide-de-camp, accompanies Sidney Johnston. General Breckinridge doesn’t recognize Harris, and he says, “General, I have a Tennessee regiment that won’t fight.” He’s embarrassed when he sees the Tennessee governor, and apologizes for his derogatory remark. He identifies the Tennessee regiment that wasn’t fighting, and Harris, who considers himself a good stump speaker, says, “I’ll go and tend to that,” and off he goes to address the 45th Tennessee.

Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston was the senior ranking general holding a field command in the Confederate forces. Fatally wounded on April 6, he became the highest ranking casualty of the war.

Johnston is directing troop movements with the tin cup he picked up earlier that day. Also remember at that time he had sent off Dr. Yandell to see to the wounded, both Rebs and Yanks. Coming upon an Arkansas regiment, Johnston shouts, “We’re going to charge the enemy! Remember, the enemy does not like cold steel. Do you hear me?” “Yes, we hear you!” they respond. The Confederates are fired up. Four brigades are ready to go. Johnston, mounted on Fire-Eater, rides along behind his advancing soldiers from Mississippi, Tennessee, Missouri, Arkansas, Alabama, and Texas. The Union line collapses from left to right. John McArthur’s three Illinois regiments, beginning with the 50th Illinois, crumble; a battery is nearly surrounded before it makes good its escape minus a gun. Next, the Union line in the Peach Orchard west of the Savannah-Hamburg Landing Road is folded back.

This is a great day for Johnston: It looks like he’s finally scored the breakthrough that will send the Confederates thundering north to Pittsburg Landing. He’s been hit four times, but only one projectile, a caliber .577 minié ball, probably fired by a Confederate, counts. Johnston sits there, and he sends off his aide, Capt. Theodore O’Hara. The only person with him at this time is Capt. W. L. Wickham. As Governor Harris rides back, he notices that Johnston looks very pale. Evidently Wickham has not noticed or not said anything about it. Harris inquires, “Are you wounded?” And Johnston says, “Yes, and I fear seriously.”

They lead Johnston’s horse down into the ravine and help him dismount. Harris gets down in a crouch and cradles Johnston’s head in his lap. They try to get some brandy down his throat. They think that he’s probably been hit in the chest because there’s not that much blood, a small trickle is coming out of his right boot; the boot, unknown to them, is full of blood. They unbutton his shirt, looking for a wound in his chest. By this time, O’Hara is back, accompanied by Col. William Preston, Johnston’s former brother-in-law. Harris is getting stiff, cradling Johnston, so Preston takes over. They try to get some whiskey down his throat; they get only a gurgle. Then they feel his chest, and his heartbeat has stopped.

Albert Sidney Johnston has breathed his last. Steps are taken to notify Beauregard. Harris tries to get on Fire-Eater, but the horse is wounded. He rides a short distance and gets another horse. Johnston is dead, and the word spreads like wildfire among the senior commanders of the Rebel army.

With Johnston dead, the Confederate commanders seek to sort out the situation. Who’s going to command? Beauregard is in the rear; Johnston had been directing the assaults. Beauregard determines to remain at Shiloh Church and, as Army commander, coordinate battle actions. Bishop Polk will command the army’s left wing and Bragg the right. They’re to resume attacking. They will continue to throw other brigades into the Hornets’ Nest fight: first A. P. Stewart’s, then in succession Shaver’s, Patton’s and Anderson’s, and finally S. A. M. Wood’s. But they’re not going to secure a breakthrough until they call on Brig. Gen. Daniel Ruggles. This will be the only day in the war that Ruggles is more than a journeyman general. He gathers artillery from all over the field. He’ll assemble 11 batteries, a total of 53 cannon, and at 4:30 these guns open fire on the Hornets’ Nest “with the force of a hurricane.”

On April 6, 1862, these 24-pounder siege guns formel part of the Union’s “last Line” at Pittsburg Landing, luring the Battle of Shiloh.

At the same time, the defending Union forces are wearing down, contracting their front, and struggling to hold their ground. Tom Sweeny’s brigade finally collapses; General W. H. L. Wallace is shot down. He remains on the field throughout the night, with rain pouring down, shot through the head. The next day Union soldiers will find the mortally wounded general and evacuate him to the Cherry Mansion, where, comforted by his wife, he dies on April 10. Prentiss’s men are surrounded, and by 5:45 p.m., 2,250 Union soldiers have surrendered.

The stand at the Hornets’ Nest buys precious time for Grant. As the Federals fend off attack after attack—ten in all—Grant orders his chief of staff, Col. Joseph D. Webster, to establish a last line of defense extending west from Pittsburg Landing. The line bristles with cannon; what remains of Sherman’s and McClernand’s divisions gathers on the right flank, fronting west.

The Union will have more than 50 cannon, including five big 24-pounder siege guns, on what becomes Grant’s “Final Line.” Fronting the Union left, facing south and anchored on the commanding bluff overlooking Pittsburg Landing, is the Dill Branch Ravine, 200 yards wide and adjacent to the river, with a vertical fall of 75 feet. High water from the Tennessee is backed up into Dill Branch for several hundred yards. The Union right flank is posted behind Tilghman Branch on a plateau overlooking the Owl Creek bottom, forward of the Savannah-Hamburg Road, the route over which the tardy Lew Wallace is approaching from Crump’s Landing. The distance between the heads of Dill and Tilghman branches is about half a mile. By 5:45, making use of the terrain that favors the defense, Grant had cobbled together a formidable line covering Pittsburg Landing, where a linkup with Wallace could take place.

As evening approaches, with the Hornets’ Nest now under Confederate control, Beauregard is faced with the choice of whether to attack Grant’s Final Line. Unbeknownst to him, William “Bull” Nelson’s division has finally arrived; one of his brigade commanders, Col. Jacob Ammen, hurries three regiments across the Tennessee on steamboats to form into line and fire a few shots as the Confederates tentatively advance. Then the word comes from Beauregard: enough for now—we’ll finish the job tomorrow. It may have been just as well: Dill Branch, with its steep banks and undergrowth, presents more of an obstacle than one might at first expect.

Brig. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson, an acquaintance of Lincoln’s, survived the bloody fighting at Shiloh only to be murdered six months later following an argument with a fellow officer.

Bull Nelson—300 pounds, six feet four—is mean as hell. He can bend a poker around his forearm. He had been a naval officer and is a close friend of President Lincoln’s. On the 29th of March, back at Columbia, Tennessee, frustrated at waiting for the completion of a bridge across Duck River, he marched his men through the river. He is eager to get here. Grant, when he leaves Savannah to come upriver, doesn’t leave specific instructions as to how Nelson’s command is to get to Pittsburg Landing. It’s going to be 12:30 before Nelson leaves Savannah. He will not bring any artillery with him because he knows the bottoms are inundated; the Tennessee River, although falling, is still high. It’s going to be a hellacious sight when Nelson arrives about 5:30, on the riverbank opposite Pittsburg Landing. Nelson estimates that between 7,000 and 10,000 Army of the Tennessee soldiers, “frantic with fright and utterly demoralized, were cowering under the river bank.” Grant subsequently questions the numbers cited by Nelson.

I applaud what Nelson does now. As he and his staff and escort see these panic-stricken men trying to get on their boat, he roars “Draw your sabers! Run over the bastards!”

As Colonel Ammen brings his men ashore they fight off the panic-stricken soldiers. They see Union cavalry come down and seek to drive the men away from the landing and up onto the bluffs. Whether it’s 6,000, 7,000, 8,000, or 11,000—the various figures given—there are a lot of panic-stricken Yankees. Among them will be Capt. John B. Myers and Col. Jesse Appler. Jake Ammen is from Georgetown, Ohio. Who else is from Georgetown, Ohio? Ulysses S. Grant.

In the evening it gets cold, and rain sets in. Grant is outside. Grant is not disturbed by the dead, but he does not like to be around hospitals and the wounded, particularly when the doctors are doing amputations. He goes into a log cabin near the landing, and when he sees it’s a hospital he can’t take it, so he walks out and stands under a tree with his hat pulled down over his eyes and with his coat pulled up.

At one point during the night, Grant’s chief engineer, Col. James B. McPherson, rides up and reports that much of the army is “hors de combat.” When asked what he would do under these circumstances—retreat? Grant answered “No! I propose to attack at daylight and whip them.”

During the night Union reinforcements continue to arrive, strengthening Grant’s line, making a counterattack possible. All of Nelson’s men are shuttled across the river by steamboats. Other divisions of Buell’s Army of the Ohio arrive during the night. They come by boat, upriver from Savannah. First will be two brigades of Brig. Gen. Thomas Crittenden’s division, then three brigades of Brig. Gen. Alexander McCook’s, and finally Col. George D. Wagner’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood’s division.

It is 7:30 and getting dark when Lew Wallace’s three-brigade division crosses Owl Creek Bridge and files into position on Sherman’s right. For both Wallace and Grant it has been a long, frustrating day, one the former will rue and seek to explain till his dying day in February 1905. When General Buell reports back to Grant, he learns that they will attack on Monday morning, April 7. Buell will be in charge on the left, Grant on the right.

Meanwhile the Confederates rest. Beauregard sends a telegram to Richmond that the army has won a “complete victory,” and he will finish it in the morning. Others are not so sure. Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest hears the noise of steamboats. He puts several men into Yankee overcoats and sends them to take a closer look: They report back that they see steamboats at the landing and soldiers debarking and marching. Forrest goes looking for somebody. It’s hard to find anybody in authority. In many places the Confederates pull back during the night. It rains. To make things worse, the “timberclad” gunboats Tyler and Lexington, anchored off the mouth of Dill Branch, keep up a harassing fire in the direction of the captured Union camps with their big eight-inch guns at 15-minute intervals.

Lew Wallace moves out in the morning, and what is he going to encounter? Preston Pond’s brigade and four cannon. Supporting Wallace are 11 Union cannon. Wallace’s men cross Tilghman Branch, drive the Rebels from Jones’s Field, but slow down as they pause to wait for Sherman and McClernand to come up on their left. So we’ve got Grant’s attack started. Cooperation between Grant and Buell’s wings will be slim to none, and as they say, Slim just left town.

At the same time that Buell sets matters into motion on the left flank, Nelson’s division on the Confederate right leads the way.

Under cover of darkness, the Confederates had pulled back southward to seek shelter from the rain and loot the captured Federal camps. That means the Federals are going to have a free ride early on as they advance. Nelson guides on the Savannah-Hamburg Road. On the left is Jake Ammen’s brigade, in the center is the brigade of Col. Sanders Bruce, and on the right in the woods is Col. William B. Hazen’s.

Before long Nelson’s brigades close on the landmarks of yesterday’s savage fight—the Hornets’ Nest—Bloody Pond, the Peach Orchard, and the Sunken Road. Here they encounter Confederates. The Rebels have something Nelson lacks: artillery. Nelson calls up two regular batteries—Capt. John Mendenhall’s Fourth U.S. Companies H and M, and Capt. William R. Terrell’s Company H, Fifth U.S. Artillery. General Hardee orders his men to attack, and they hammer the Yanks near Bloody Pond. To the Confederate left, a second attack drives Hazen back to the Sunken Road with heavy losses.

Remember, as the two armies meet here on April 7, there are dead and wounded scattered about from the previous afternoon’s fighting, particularly around Bloody Pond. Dead animals and dead men lie sprawled with their faces and heads in the water. Now besides the problems of empty canteens and poor water discipline, the situation is compounded because wounded men develop thirst.

The Confederates advance again, but Hardee’s warning that there are friendly troops fronting his lines proves a disaster when the Yankees open fire. Hazen’s brigade, supported by some of Crittenden’s bluecoats, charge and capture three cannon manned by the Washington Louisiana Artillery. With Buell’s arrival, the Yankees have about 28,000 men on the line, of whom 17,000 belong to the Army of the Ohio. The Confederates have perhaps 20,000 engaged. This shows a loss of command and control by the Confederates. The Confederates counterattack and drive Hazen’s men back again. The fighting in this sector then stabilizes until noon, when Union troops break the impasse and force back Hardee’s right.

The Confederates fare little better against the Yankees in the center, near Duncan Field, west of the intersection of the Sunken Road and the Corinth Road. Duncan Field is important primarily on April 6, when the Confederates still have the offensive. Duncan Field gets glossed over once the Union seizes the initiative. Again fighting rages in this area as soldiers of Buell’s Army of the Ohio battle Breckinridge’s butternuts. One of the advantages the Confederates have on day two is that the bluecoats don’t make good use of their artillery, principally because the Army of the Ohio commits only three batteries. Nelson, on the left, has no batteries with him; they have to give him the guns that come up with Crittenden. The Confederates at the same time make effective use of their cannon as they fight for time. Another problem is on the Union right. Lew Wallace, after securing Jones’s Field, has to wait till after 10 a.m. for Sherman and McClernand to cross Tilghman Branch on his left, and then engage the foe. Patrick Cleburne with 800 men counterattacks the Yankees, but he’s driven back.

By midday on April 7 Grant and Buell’s men succeed in driving Beauregard’s men southwestward. The Confederates make a series of stands, but in each case they are forced to give ground. Numbers tell: Buell and Lew Wallace have brought fresh troops to the battlefield, while only a handful of men reinforce the Confederates.

Beauregard realizes that his position is weakening: He pulls back to the Purdy-Hamburg Road. A key feature in the struggle here is Water Oaks Pond. Again, the Rebels make good use of their artillery, while the Federals do not. The Confederates are fighting like hell; they’ve got to because if the Union forces break through the Confederate left and reach Shiloh Church, their direct line of retreat to Corinth will be endangered. Advancing against them, guiding on the Corinth Road, is Brig. Gen. Alexander McCook’s division, consisting of Brig. Gen. Lovell Rousseau’s and Col. Edward Kirk’s brigades. Off to his left is Thomas Crittenden’s division. To the right are McClernand, Sherman, and Lew Wallace, threatening to turn Bragg’s left and reach Shiloh Church.

The Confederate situation is desperate. McCook’s Federals are reinforced by a third brigade, headed by Col. William Gibson. The Confederates continue to give ground, falling back from Duncan Field to beyond Water Oaks Pond. Beauregard’s headquarters is next to the Shiloh Church. The Corinth Road, running by the church, is the best and shortest route to Corinth, so they must hold this area as long as possible. Beauregard calls for two successive counterattacks. S. A. M. Wood’s brigade spearheads the first. The men wade Water Oaks Pond and slam into McCook’s division. Kirk’s reinforced brigade is running low on ammunition. It pulls back; the Rebel counterattack has bought more time. However, when Gibson arrives, he stops Wood and drives him back.

The situation is increasingly desperate. To the rescue comes Preston Pond’s Louisiana boys, who have been ordered all over the field without seeing much action since early morning. This buys some time, but time is running out. One of Beauregard’s staff officers turns to the Confederate commander and remarks that the army resembles a lump of sugar, soaking wet, holding together for the moment, but ready to dissolve. Beauregard understands. He orders a withdrawal. Buying time yet again, Col. Robert F. Looney’s 38th Tennessee heads a final charge; before long the Confederates retreat in earnest. The time is 3:30 p.m.

Neither Grant nor Buell orders a pursuit. Grant has had enough: His men are exhausted, and he hesitates to issue orders to Buell. In truth, both sides are fought out. More than 23,700 men are killed, wounded, or captured at Shiloh, more than in all of the previous wars of the United States put together. The Confederates suffer 10,694 casualties to the Union’s 13,047. Grant came under heavy criticism but retained his command; for years to come Confederates would ponder the what-ifs of the battle that represented their best chance to stop and reverse the Union advance through west Tennessee and into north Mississippi.