SEPTEMBER 17, 1862

Beginning September 4, 1862, long infantry columns of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia splashed across the Potomac River at White’s Ford to enter the state of Maryland. On the far shore a band played inspiring music, including the popular secession air, “Maryland, My Maryland.” The Rebel soldiers were sunburned and weathered, and their threadbare gray and butternut uniforms were in tatters—many marched barefoot or in worn-out shoes—but the confidence and morale of Robert E. Lee’s veterans was superb. Lt. Col. E. Porter Alexander, an artillery officer in Longstreet’s wing, recalled that Lee’s army “had acquired that magnificent morale which made them equal to twice their numbers, and his confidence in them, & theirs in him, were so equal that no man can yet say which was greatest.”

Since late June 1862, Robert E. Lee’s veterans had fought an extraordinary series of campaigns and battles that had carried them from victory to victory—from the gates of Richmond to the doorstep of the northern states. In early summer Confederate forces had faced a major Federal offensive against Richmond led by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, whose march up the peninsula between the York and James Rivers had pressed to within seven miles of the Confederate capital. Gen. Robert E. Lee had assumed command after the wounding of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at the inconclusive Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks), just east of Richmond, on June 1, 1862. Quickly gathering control of the army, Lee struck at McClellan on June 26, fighting a seven-day series of successful but often poorly coordinated battles at Oak Grove, Mechanicsville, Gaines’s Mill, Garnett’s Farm, Savage’s Station, White Oak Swamp, Glendale, and Malvern Hill. By the beginning of July, despite problems of communication and coordination, the Confederates had blocked McClellan’s advance and bottled up his army at Harrison’s Landing on the James River.

With McClellan inactive, Lee now faced a second threat. Maj. Gen. John Pope’s 50,000-man Army of Virginia that had threatened the Shenandoah Valley was now maneuvering east of the Blue Ridge mountains to support McClellan. Lee detached one of his trusted lieutenants, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, with 24,000 men, to maneuver toward Gordonsville, Virginia, to delay Pope’s advance. After an engagement between Jackson and a force under Federal Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks at Cedar Mountain on August 9, Lee, learning that McClellan had been ordered to redeploy most of his forces to join Pope in Northern Virginia, marched north with Longstreet’s wing to link up with Jackson.

Splitting his army on the line of the Rappahannock River, Lee sent Jackson north on a turning movement against Pope’s right flank, and the armies met on August 28–30 at the Second Battle of Manassas. After severe action between Pope and Jackson on August 29, Longstreet’s wing enveloped the Federal left on August 30, sending Pope’s forces in retreat across Bull Run to Centreville.

Maintaining the offensive, Lee again moved against his enemy’s flank, striking toward Fairfax Court House. After a fierce battle at Chantilly, Virginia, Pope withdrew into the defenses of Washington. After three months in command of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee had conducted a remarkable series of battles and campaigns that resulted in the defeat of the two Federal Armies that threatened Richmond and driven most of the North’s forces back into the defenses of Washington. Despite heavy losses in men and materiel—the Army of Northern Virginia had suffered more than 29,000 casualties since June 1—Lee was determined to keep the initiative.

Rather than hurl his army against Washington’s formidable ring of forts, Lee decided to take the war into the North. In a letter to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Lee argued that he could not afford to remain idle. By entering Maryland and perhaps Pennsylvania, he could shift the armies from war-ravaged Virginia and gather supplies in the fruitful farm country of central Maryland and Pennsylvania’s Great Valley and perhaps rally Marylanders to the Confederate cause. Further, a Confederate victory on Northern soil might force the Lincoln government to open negotiations with the South.

As the Rebel forces, more than 50,000 strong, crossed into Maryland and advanced on Frederick, Abraham Lincoln acted quickly to counter the threat, sacking Pope (whom he had named head of the Army of Virginia just months earlier) and restoring the charismatic McClellan to the command. Moving with uncharacteristic speed, McClellan by September 7 had established his headquarters north of Washington at Rockville, Maryland, and began sending his army—a force of some 80,000 men—marching toward Frederick on a broad front in pursuit of Lee.

After occupying Frederick on September 7, Lee, on the ninth, devised a bold plan spelled out in Special Order No. 191. Lee planned to send three columns under Stonewall Jackson to capture the strategic communications center of Harpers Ferry, to guard his rear and to open communications with the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson was then to link up with the rest of the army 12 miles north of Harpers Ferry at the small town of Boonsboro, Maryland. From there, if all went well, Lee could maneuver into Pennsylvania to meet McClellan on ground of his own choice. Lee’s army resumed its march on September 10 with Longstreet and Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill headed west through the gaps in South Mountain toward Boonsboro and Hagerstown, while two of Jackson’s columns under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and Brig. Gen. John G. Walker headed westward to threaten Harpers Ferry from north and south of the Potomac. Jackson with three divisions headed west to recross the Potomac at Williamsport and approach Harpers Ferry from the west.

On September 12, McClellan’s vanguard reached Frederick, and on the following day the Federal commander was overjoyed at the discovery of a lost copy of Lee’s Special Order No. 191, found wrapped around three cigars in an abandoned Confederate campsite. With detailed knowledge of Lee’s timetable and movements, McClellan now believed that he could defeat the Rebel forces piecemeal before they could reunite. Accordingly, McClellan sent his forces marching toward Boonsboro in pursuit of Lee and Longstreet.

While a jubilant McClellan marched out of Frederick, Jackson’s columns closed on Harpers Ferry. By September 13, McLaws seized Maryland Heights and Loudoun Heights, high ground commanding the town and the Shenandoah River. By the following day, Jackson had closed the trap from the west, and his artillery opened fire on the Federal garrison.

While Jackson invested Harpers Ferry, Lee left forces under D. H. Hill to hold several of the South Mountain passes and accompanied Longstreet to Hagerstown. On the night of September 13, however, he became aware that McClellan was closing in on South Mountain in his rear and ordered Longstreet to countermarch and rejoin Hill. On the 14th, McClellan struck the Confederates, forcing his way through Crampton’s Gap and battering the defenses of Turner’s and Fox’s Gaps. After a day of fierce fighting, compelled to abandon the South Mountain gaps, Lee with Longstreet’s and D. H. Hill’s people withdrew southward to the small village of Sharpsburg, close to the Potomac along Antietam Creek.

On the morning of September 15, the 12,000-man garrison at Harpers Ferry surrendered. Acting decisively, Lee ordered Jackson to join Longstreet and concentrate the army at Sharpsburg. Leaving Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill’s division to parole the large number of Federal prisoners at Harpers Ferry, Jackson crossed the Potomac near Shepherdstown on September 16 with three divisions, and his exhausted men marched toward Sharpsburg.

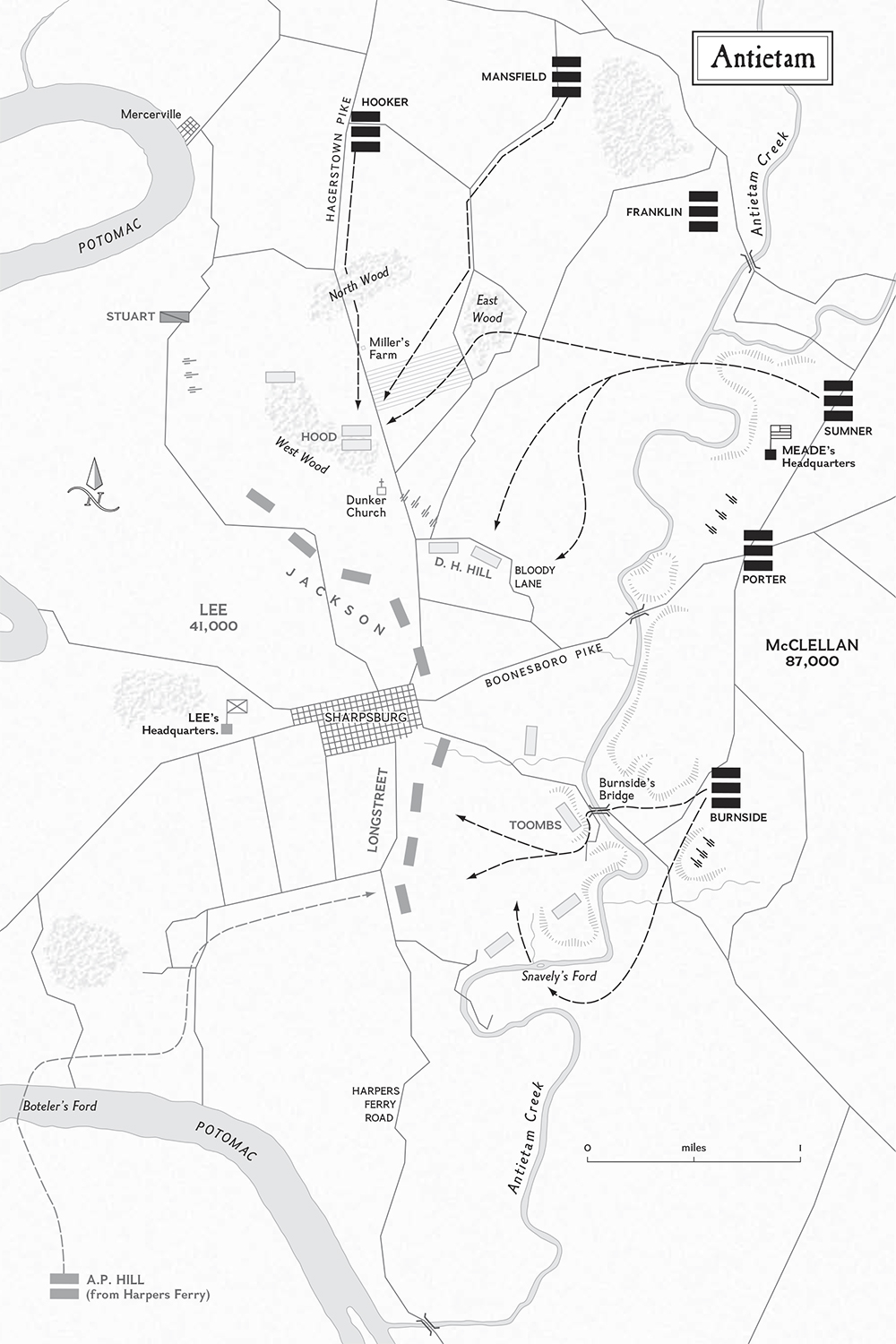

Throughout the day on the 16th both armies gathered at Sharpsburg, exchanging artillery fire across the valley of Antietam Creek. As Jackson’s troops straggled in from Harpers Ferry, Lee posted his divisions along a north-south ridge behind Antietam Creek with both his flanks anchored on commanding ground near the Potomac River. In his front, three bridges crossed Antietam Creek, an upper bridge, about two and a half miles northeast of Sharpsburg, the middle bridge carrying the Boonsboro Turnpike, and a lower bridge just southeast of Sharpsburg. Lee chooses to defend only the lower bridge.

Instead of taking advantage with his superior strength—at midday on the 15th McClellan unknowingly had faced only 19,000 Confederates—McClellan spent the entire day of the 16th organizing his troops, allowing Lee valuable time to concentrate. Finally, at sunup on September 17, 1862, the Army of the Potomac launched its massive assault against Lee’s outnumbered forces.

North of the David R. Miller cornfield is the western fringe of the North Woods, bounding the Hagerstown Pike on the west, and extending down toward the southwest into a pocket with limestone outcroppings. West of these woods lies Nicodemus Heights. One-half to three-quarters of a mile behind Nicodemus Heights is a meander bend in the Potomac River. Lee positions most of Jeb Stuart’s cavalry there, along with the horse artillery, supported by Jubal Early’s brigade. The Rebels have lots of manpower and artillery on Nicodemus Heights.

Lee posted his forces behind Antietam Creek west of Sharpsburg. McClellan attacked Lee’s left at 6:15 a.m. with two corps, resulting in desperate fighting in the Cornfield and East Woods. By 9 a.m., assaults by a third Federal corps forced the Rebels back into the West Woods and around the Dunker Church. Later Federal assaults nearly broke through Lee’s center in the Sunken Lane and fronting the Hagerstown Pike. By late afternoon Federal forces crossed the Lower Bridge and drove back Lee’s right, only to be turned back by Confederate reinforcements arriving from Harpers Ferry.

Jackson’s wing holds the army’s left. South of Miller’s Cornfield, extending out about one-quarter of a mile northwest from West Woods, are the “Stonewall” and Capt. J. E. Penn’s brigades, supported by two brigades, Col. James Jackson’s and William E. Starke’s. Together they constitute a division commanded by Brig. Gen. John R. Jones, one of six failed soldiers that Stonewall seems to push ahead in spite of their failings. On the east side of Hagerstown Pike from left to right are Cols. Marcellus Douglas’s Georgia Brigade and James A. Walker’s brigade—men of Georgia, Alabama, and North Carolina.

On the Union right is Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, directing the operations of the I Corps. His men are deployed north of Miller’s Cornfield—soon to become “the Cornfield.” His I Corps is the old III Corps, Army of Virginia, commanded by Irvin McDowell in the Second Manassas Campaign. McDowell had been relieved in the first week of September, and Hooker, new to corps command, leads the I Corps. The initial punch is going to be by the Yankee right, a haymaker powered by two corps pushing south and southwest and converging on a small white brick structure, the Dunker Church.

At 4 p.m. on September 16, the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves comes down the Smoketown Road and into the East Woods and skirmishes with John B. Hood’s men. If Lee had any delusion about where General McClellan’s opening blow will come, Hooker has tipped his hand. Maj.

Gen. Joseph K. F. Mansfield forms up on the Smoketown Road, on the George Line Farm, a mile and a half to the left and rear of Hooker’s position. It rains on the night of the 16th; it quits toward morning, and a ground fog blankets the area.

Hooker positions Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s brigade, which would receive its nom de guerre, the “Iron Brigade,” in action at South Mountain, astride the Hagerstown Pike. Gibbon’s Black Hats, as they are also known, are supported by Company B, Fourth U.S. Artillery. (Note that artillery units do not officially become “batteries” until after the Civil War.) Guiding on the Hagerstown Pike, they advance southward.

What Hooker should have done is send a strong force against Nicodemus Heights to drive Stuart and the horse artillery from there, but he does not. Advancing along the axis of the Smoketown Road, which converges with the Hagerstown Pike at the Dunker Church, is Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts’s division, spearheaded by Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s brigade of Brig. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s Second Division. Seymour, a member of the West Point class of 1846, will prove to be a better artist than a general. Meade’s other two brigades are in reserve. Hooker’s artillery opens fire. His command post is initially near Joseph Poffenberger’s barn; aware of the value of public relations, he has several newspaper correspondents with him.

The attack opens shortly after 6 a.m. Seymour’s brigade is supported by Ricketts’s three brigades—Brig. Gen. Abram Duryee’s, Col. William Henry Christian’s, and Brig. Gen. George Lucas Hartsuff’s. They advance through the East Woods, guiding on the Smoketown Road. If all goes well, they will crush Walker’s Confederates and reach the Dunker Church. Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday’s I Corps, a division led by Gibbon’s brigade, must smash the right of the Stonewall Division and the left of Douglas’s Georgians, if they are to reach the Dunker Church. If the Yankees do so they will hold key ground that could give McClellan a great victory.

They’ve got the cornrows in front of them as they move forward through the fog, making them hard to see. Seymour’s Federals pound Walker’s brigade. Two Confederate brigades rush to reinforce Walker. The Yankees punch their way forward, rolling back Walker. Gibbon’s brigade, backed by Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick and Col. Walter Phelps, assails the Stonewall Division. J. R. Jones, slightly wounded, heads for the rear and the Stonewall Division gives way. The bluecoats close to within 200 yards of Dunker Church. But then they’re engulfed by Rebs when Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood counterattacks. Hood’s people had not eaten a hot meal in more than 48 hours. They are called to battle from their cornpone and coffee and are as mad as hornets. Hood’s division fans out as it storms ahead. The famed Texas Brigade led by Col. William Wofford surges into the western part of the Cornfield, while Hood’s right wing—Col. Evander Law’s brigade (Alabamians, Mississippians, and Tarheels)—sweeps the Yanks from the east side of the Cornfield and enters the East Woods. Among the Union casualties is General Hooker, shot in the foot.

Hooker’s biggest mistake was not coordinating with Joseph Mansfield. Mansfield’s men are eating breakfast when Hooker launches his attack. This is fatal for the Federals. If Mansfield had been closed on Hooker, Hood’s savage surge into and through the Cornfield may have come to naught, because of the difference in manpower. Now, too late, Mansfield comes up. He is 58 years old, but looks as old as Moses with his white hair and beard. Up to two days before, he’d never held a major line command; he’s been a senior staffer since 1853. Now he leads a corps.

The XII Corps includes a number of regiments that have never seen the “elephant.” Brig. Gens. George H. Gordon’s and Lt. Col. Hector Tyndale’s brigades are exceptions, having experienced lots of fighting. They’ve given Stonewall Jackson hell in the Shenandoah Valley and at Cedar Mountain. Mansfield brings them forward by regimental column by company, a formation that has a narrow front and great depth. A soldier in the Tenth Maine likened the corps to a huge barn as it lurches ahead. They come under fire from soldiers on the high ground to their front. Mansfield, uncertain as to whether these people are friends or foes, rides forward to reconnoiter and is shot in the chest. He is taken to the Line Farm, but dies within 24 hours. Brig. Gen. Alpheus “Old Pop” S. Williams takes command of the XII Corps and sends Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene, 61 years old, down the Smoketown Road with two brigades. Taking over Williams’s division is Brig. Gen. Samuel Wylie Crawford. A doctor at Fort Sumter, he had switched to the infantry, as he knows that if he stays a doctor his opportunities for promotion will be limited. Crawford, with his two brigades and Col. William B. Goodrich’s of Greene’s division, enters the East Woods and sweeps westward. There is savage fighting as the battle ebbs and flows through the East Woods and the Cornfield.

Gordon’s brigade includes the Second Massachusetts, the Republican Harvard Regiment. In it is Capt. Robert Gould Shaw, who will eventually lead the 54th Massachusetts and die in the storied attack on Fort Wagner. Out in the Cornfield, Shaw is wounded. In another regiment, the 27th Indiana, is the tallest man in the Union Army. He’s Capt. Richard Van Buskirk, 6 feet 11 inches, 225 pounds. When mustered in, Van Buskirk’s Company F lists 35 of its 100 men as at least six feet tall and soon will be known as the “Giants in the Cornfield.” (Coach Bobby Knight a century later may have found a few recruits for his “Fighting Hoosiers” in this regiment.) The struggle between Gordon’s people and Hood’s is particularly bitter, as photographs of the aftermath taken by Alexander Gardner on September 19 show.

By 9 a.m. Crawford’s men are fought out. They cling to the Cornfield but they have taken frightful casualties. George Greene pushes ahead to within a short distance of the Dunker Church before he is pinned down.

Recognizing the grave Yankee threat to his left, Lee shuttles brigade after brigade into the battle, thinning out other parts of his line. It is a tactic he will practice all day. For now it works. With Hooker and Mansfield down, the Union attack on Jackson’s wing responsible for holding the Rebel left stalls. About 9 a.m., after a brief lull in the fighting, the Federal II Corps crosses Antietam Creek planning to crush the Confederate left flank before wheeling south toward Sharpsburg.

The Union II Corps is commanded by Maj. Gen. Edwin Vose Sumner, who entered the Army as a lieutenant in 1819; he did not attend West Point. Sumner has the courage of a lion, but as a leader he commits his corps piecemeal and gets into even more trouble than McClellan does when the going gets tough. His men cross Antietam Creek at Pry’s Ford.

The first Yankee division across is led by Connecticut bachelor “Uncle John” Sedgwick, a major general who plays solitaire and is popular with his soldiers. Unfortunately for the Union, Sumner accompanies Sedgwick. He does not stay behind to coordinate the movements of the remainder of his corps, the divisions of Brig. Gen. William “Old Blinkey” French and Maj. Gen. Israel B. Richardson. On the left of Sedgwick’s division, marching by column as it approaches the East Woods, is Brig. Gen. Willis Gorman’s brigade; on Gorman’s right is a man who had to be a general, with a name like Napoleon Jackson Tecumseh Dana; and on the right is the Philadelphia Brigade led by the “Havelock” of the army, Brig. Gen. Oliver O. Howard. Sedgwick’s people halt on entering the East Woods, form into line of battle, and face southwest toward the West Woods.

As they move out it is very quiet. Birds fly about willy-nilly—perhaps shell-shocked. Dead and wounded men, the human wreckage of several divisions, are scattered about the Cornfield. We’ll rejoin Sedgwick’s men when they enter the West Woods. General French is trailing Sedgwick by 20 to 30 minutes. French comes out of the woods, and he can’t see where Sedgwick has gone. The north-south ridge—today’s location of the visitor center and New York State Monument, constitutes a critical viewshed that separates French from Sedgwick as he crosses the Hagerstown Pike and enters the West Woods north of Dunker Church to meet death and destruction. Their formation invites disaster. They advance by successive brigades, the men in double ranks, elbow touching elbow, the files closers several steps behind the rear rank of each brigade.

We can see what the Federals are trying to accomplish by sending Sedgwick’s division up the middle into the West Woods—on the far side of the woods is lower ground that extends south as far as Sharpsburg. Sedgwick’s people are hemmed in by the woods. Trees in front of them, trees behind them, and trees to their left. Soon there will be Rebels in front of them, Rebels to their left, and Rebels swinging around to get into their rear. They’re going to be a very uncomfortable bunch, and they will lose 2,200 men in 20 minutes, out of the 5,700-strong division.

Willis Gorman’s men halt. In front of them, some 60 yards away, they see Confederates. Jubal Early’s brigade has been rushed here and is posted in a wood road. Nearby is Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays’s Louisiana Tigers, already bloodied by their fight against the Union XII Corps. Gorman’s men open fire. Fifty yards in back of them is Dana. Dana’s bluecoats can’t fire. If they do, they’ll shoot into the backs of Gorman’s people. Fifty yards behind Dana is Howard. Howard can’t fire. Thousands of Yanks halted with only Gorman’s brigade engaging the Confederates to their front.

Coming up from the south is Lafayette McLaws’s division, with Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolinians, Brig. Gen. Paul Jones Semmes’s Georgians, and Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippians. McLaws’s division had crossed the Potomac on the night of the 16th and was being held in reserve until rushed by General Lee to the point of danger. He is followed by Brig. Gen. John G. Walker’s two-brigade division—sent from Lee’s extreme right, near Snavely’s Ford, where as yet Burnside’s command is not a threat—and G.T. “Tige” Anderson’s brigade. Sedgwick’s men can’t maneuver to cope with these Rebel reinforcements. The only Yankees who can fire at these newcomers are those on the left flank. How much more valuable it would have been if Sedgwick had a regiment moving in column on that flank. If so, that regiment could have halted and faced the newcomers.

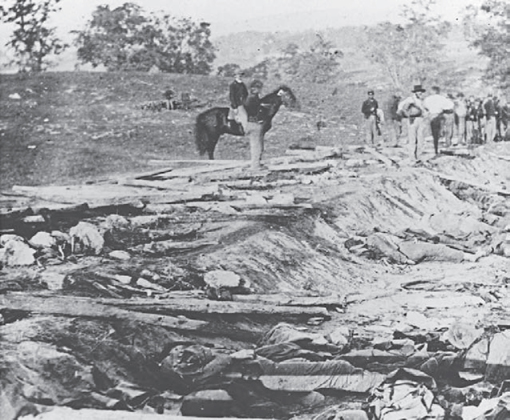

Confederate dead lie scattered on the ground around the Dunker Church, a symbol of the bloody reality of the fighting at Antietam.

Men in Howard’s brigade panic and fire into Dana’s to their front. Early in the fight, Sedgwick is wounded badly and has to leave the field. You can argue that the Yankees would have been better off if General Sumner had also been taken off the field instead of suffering a hand wound and remaining with his corps. Also wounded is Capt. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the future Supreme Court justice. What’s left of Sedgwick’s division flees into the West Woods, and as they do, the Confederates pursue. Unfortunately for the Confederates, the ever aggressive division led by George Greene and the artillery batteries of the I and XII Corps blast the advancing Rebels and turn back Kershaw’s onrushing South Carolinians.

The next Yankee troops that appear just south of the West Woods at the Dunker Church are George Sears Greene’s. Prior to Sedgwick’s arrival there was a half-mile gap between Greene and the southwest corner of the Cornfield where Crawford’s advance had stalled. Col. Stephen D. Lee’s Rebel artillery battalion is initially positioned on a spur between today’s visitor center and the Dunker Church. Greene and some of his men reach Dunker Church after Sedgwick has run into disaster. Greene is not reinforced and has to fall back in the face of a Rebel counterattack.

During the battle you see a major difference between Robert Lee’s and McClellan’s leadership style. Lee rides about the field. By 10 a.m., he is up near the Dunker Church, when a begrimed young private comes up and speaks to him. Lee does not recognize him until he exclaims, “Father, don’t you know me? This is your son Rob!”

For much of the morning McClellan remains in and around his Philip Pry House headquarters. At times he goes up into the attic, stands on a barrel, and from that elevated height looks out the trapdoor to the roof. Other times he goes over to a fence where key staffers study distant battle actions on the far side of Antietam Creek through telescopes and binoculars. He crosses to the west side of the Antietam only once. There he meets and confers with his close friend and VI Corps commander, William B. Franklin. General Franklin, number one in the 1843 class of West Point, arrives from Pleasant Valley in time for W. S. Hancock’s brigade to support Union guns that discourage the Confederates as they attempt to follow up the defeat of Sedgwick’s division. Franklin goes to McClellan, which is strange because Franklin is also cautious. He urges McClellan to commit his VI Corps. Unfortunately for the Federals and fortunately for the Confederates, Sumner, known as the “Bull of the Woods,” has not been wounded badly enough to be sent to the rear. He has been shocked and sickened by what has happened to Sedgwick’s division. Sumner is pessimistic about the chances of Franklin’s scoring any successes. In view of Sumner’s attitude, McClellan decides it would be unwise to commit Franklin. Franklin’s would be a good corps to be in because at veterans’ reunions you could boast that you were at Antietam but were unlikely to be a casualty. Indeed only one of Franklin’s six brigades, Col. William H. Irwin’s, is seriously engaged, when late in the day the Seventh Maine is sent on a “mission impossible” to attack across the Sunken Road onto the Piper Farm, which is easily repulsed.

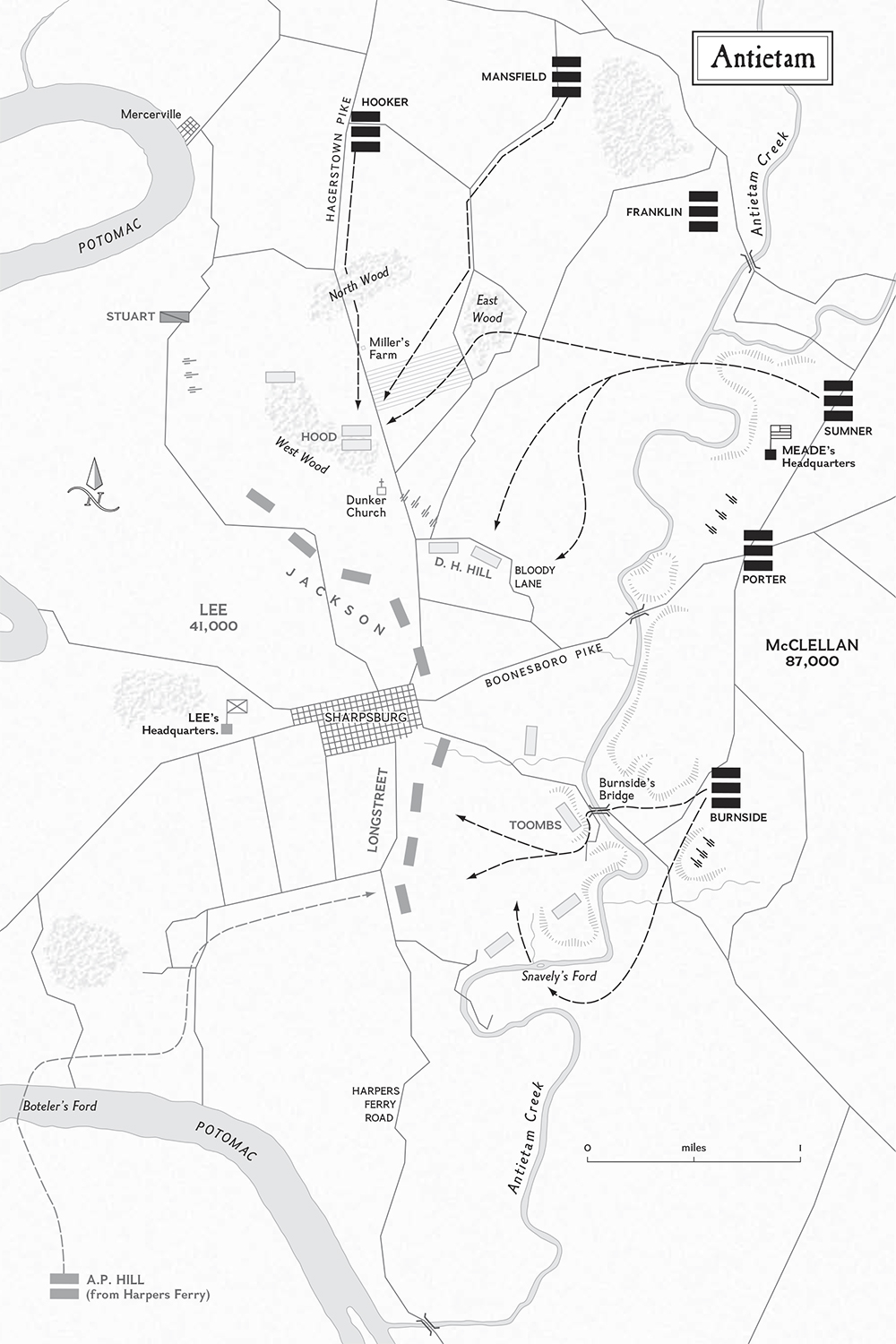

After his success in forcing McClellan away from Richmond during the Seven Days campaign, Gen. Robert E. Lee took command of the forces he named the Army of Northern Virginia.

With Greene and Sedgwick thrown back, the combat on the Confederate left draws to a close. The next Union advance will be against the Confederate center. There the Confederate infantry are deployed facing north along a sunken farm road to the north and east of the Piper Farm.

When Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill’s division arrives on the field, it is assigned to defend the Confederate center. Hill has five brigades. Initially, three of these advance northward and join in the fight for the East Woods. Col. Duncan McRae’s and Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley’s people are hit hard, and they will be pulled out of the line; Col. Alfred Colquitt falls back to the Sunken Road. His brigade is on the left, Brig. Gen. Robert Rodes’s Alabamians in the center, and Brig. Gen. George B. Anderson’s North Carolinians on the right. Before the Union onslaught begins, Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson arrives with his division. Dick Anderson won’t be here long: He’s wounded. The Confederate artillery is on high ground in a cornfield behind and to the northwest of the Piper House overlooking the Sunken Road.

Sumner has lost control of his corps. He should have stayed at Pry’s Ford and let Sedgwick run his show. When Sumner’s Third Division under General French crosses Pry’s Ford, there is no one there to tell him where to go. He veers south. In his southward march he crosses a ridge, and his right flank passes on either side of the fire-gutted Samuel Mumma House. He advances in the same formation as Sedgwick, by successive brigades, one behind the other. The Confederates in the Sunken Road (soon to become known as “Bloody Lane”) throw down rail fences creating breastworks.

When French passes the Mumma House ridge he advances through a hollow and up a second rise. If you are with the Fifth Alabama in the Sunken Road, you will see the Yankees when they emerge from the hollow less than a hundred yards to your front. If your unit is the Sixth Alabama, you’re on lower ground. The Yankees are going to be within 60 yards before you see them. The Sunken Road is a natural trench for the Confederates, but if the Yanks can gain and hold the high ground overlooking the right flank of the lane here—to Rodes’s right and G. B. Anderson’s left—the Rebs are going to be in deep trouble. The Sunken Road bends here and angles to the southeast; any Yankees on that rise can fire straight down a section of the lane. Bloody Lane is now packed with Reb infantry since four of Dick Anderson’s brigades— Roger Pryor’s, Carnot Posey’s, Alfred Cummings’s, and A. R. Wright’s—have come forward through Piper’s Cornfield and crowd into the Sunken Road. French’s first two brigades, Brig. Gen. Max Weber’s leading, trailed by Col. Dwight Morris’s, don’t fare well, but Nathan Kimball’s combat veterans do. They seize the high ground and cling to it in spite of heavy casualties until midafternoon.

Known for some time as the “Young Napoleon,” Maj. Gen. George McClellan is pictured fifth from the left with his staff officers.

Sumner might as well have been on the moon for the command and control he is exercising over French and Richardson, his First Division commander. French attacks about 9:30 a.m., and by 11 a.m. he is stymied. Richardson’s division crosses the Antietam an hour after French; he advances on French’s left. But French has already been checked.

Richardson, an “old Army Man,” was a farmer out in Michigan when the war began. The first of his brigades to reach the Roulette Farm is one that today enjoys much esteem: the Irish Brigade, led by Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher. An Irish revolutionist, he was sentenced to death by the Queen’s Government in 1849, but world opinion resulted in his exile to Tasmania. He escaped and made his way to New York City. The Irish community has a strong militia organization in New York City, and Meagher fit in well. As the Civil War approached, the Irish looked forward to it as a way to get military experience. There were two New York Irish brigades, and many of their leaders, after the war, expected to invade and seize Canada as the first step toward the independence of Ireland. Michael Corcoran commanded one and Meagher the other. At Antietam, Meagher’s Irish Brigade consists of the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York. Also present is the 29th Massachusetts, a regiment of Protestants.

Another interesting person in the brigade is Father William Corby. He’s the chaplain of the 88th New York. He will not hear confessions from anyone in the Bay State regiment. The Irish Brigade will be committed first. Richardson will do as Sumner does; he commits his brigades piecemeal.

Among the Confederates defending the Sunken Road is Col. John Brown Gordon of Georgia. He lives a long time, more than 30 years after the war. He has a faculty that everybody wishes they had but few do: He can remember conversations word for word. Gordon recalls that early that day, General Lee comes along; he speaks to Gordon and tells him that he must hold this position. Gordon replies, “We will be here ’til the sun goes down or victory is won.” The Confederates have already repulsed French. Some of Kimball’s men cling to the high ground. Meagher’s brigade advances. Does Meagher lead his men? Whether he is drunk and falls off his horse or whether he is wounded in the fighting, no one will know. The right flank comes over the hill overlooking the Sunken Road. Meagher’s men are armed with muzzle-loading smoothbore muskets with a range of about 75 yards. And for the next 30 minutes, the Irish Brigade battles the Sunken Road Confederates at point-blank range before pulling back.

The next brigade that comes up is Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell’s. It includes the Fifth New Hampshire, led by ex-sailor Col. Edward Cross. He’s tough and always binds a red silk bandana around his bald head to shield it from the sun. Another of Caldwell’s colonels is Francis Barlow, leading the 61st and the 64th New York. Barlow, a wealthy lawyer, looks like he buys his clothes from Goodwill Industries. He carries a very heavy sword for laying across the backside of slackers. Future general Nelson A. Miles, who was a 22-year-old clerk back in the Bay State when he joined the 22nd Massachusetts, is here as a lieutenant colonel. They gain the high ground overlooking an angle in the road adjacent to Roulette’s Lane. From that ground they fire down into the Sunken Road. For the Confederates this section of the road becomes a death trap. From this time on the sunken farm road will be recalled as the Bloody Lane.

Gordon has a chance to make good on what he had earlier told General Lee. He’s been wounded four times in his extremities. You always see the same side of Gordon’s face in photographs today. Why? He takes a fifth bullet through the face and he falls. He is fortunate that he already has a bullet hole in his kepi too or he would have drowned in the welter of his blood.

With Gordon down, command passes to Lt. Col. James Lightfoot. It is a bad time for both Lightfoot and his fellow Confederates. Rodes now calls for Lightfoot to pull back his regiment’s right two companies, so they can fire directly into Barlow’s people ensconced on the high ground overlooking the Sunken Road. Lightfoot misunderstands him and shouts, About Face! Forward March! He and his Alabamians head back over the ridge toward the Piper House and barn. Col. Edwin Hobson of the Fifth Alabama looks to his right and sees the Sixth Alabama next to him, fleeing. Retreating in good order, I might add, because soldiers in their memories never flee. The Yankees punch a hole in the Rebel line into which rushes Col. John R. Brooke’s brigade of Israel Richardson’s division. The Federals pour through and exploit the gap in the Rebel line. They reach Longstreet’s headquarters at the Piper House. They are in the Piper barnyard and Piper Orchard.

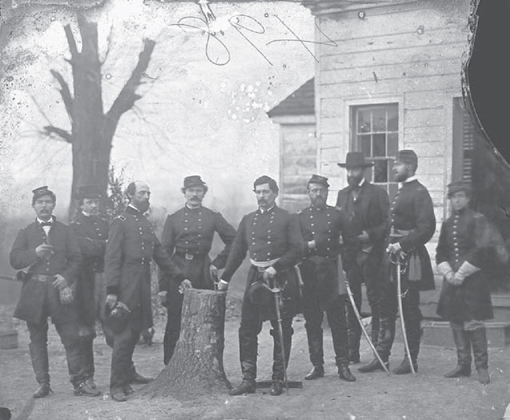

Confederate dead lie in the Bloody Lane in this photograph taken two days after the battle.

Once again bold leadership turns the tide. There stands Longstreet. He has a badly blistered foot and is wearing a house slipper. He holds the horses of his staffers to enable them to help man cannon. D. H. Hill has picked up a rifle and has rallied several hundred infantrymen. Because of the heavy fire of the Confederate artillery, this small force of Confederate infantry slows the Yankees. Dick Richardson hastens to the rear to bring up artillery, and while directing the fire of one of his few supporting batteries, he is mortally wounded by a ball of spherical case shot, fired by a Rebel battery.

The Union surge is checked and turned back by the resolute stand of a handful of Confederates. Too much time passes before Union Brig. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock arrives to take command. Opportunity has knocked once again for the Confederates, and they have met the challenge.

As Union attacks on the Confederate left and center sputter to a halt, to the south of the Boonsboro Turnpike, southeast of Sharpsburg, Ambrose Burnside prepares for an assault against the Confederate right. To do so, however, his men will have to cross Antietam Creek under enemy fire from a brigade of Georgians stationed atop a wooded bluff just past the west bank of the creek. A single narrow stone bridge there offers a crossing point, but the cost will be fearful. Portions of Burnside’s command probe southward, looking for another place to ford the creek; as they do so, Lee, with left and center mauled, wonders whether reinforcements will come from Harpers Ferry in time to shore up the line.

The Confederates have a brigade of Georgians watching the lower bridge. It is commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs, a bombastic drinker. A politician and former U.S. senator, his ambition is to be president of the Confederacy, but the best he gets in February 1861 is secretary of state. That’s not a good position from which to be elected the second president of the Confederacy. He left the secretary of state position knowing that the American public frequently elects military heroes to their highest political office. He has little use for Robert E. Lee and other West Pointers. He has just been released from arrest for challenging a superior officer, and he wants success in a big battle, and then he will leave the army. He has three Georgia regiments and a handful of South Carolinians, 502 men, and two batteries of artillery, Capt. John L. Eubanks’s Virginia Battery and a company of the Washington Artillery. They are on high ground west of the bridge. Initially guarding Snavely’s Ford and the Rebel right is John G. Walker’s division. About 9 a.m., with nothing happening at Snavely’s Ford, Walker is sent north to West Woods, and his arrival there helps spell disaster for “Uncle John” Sedgwick’s division.

Burnside is charged with crossing Antietam Creek with the IX Corps. With Burnside commanding the Army of the Potomac’s right wing, the IX Corps is commanded this day by Brig. Gen. Jacob Dolson Cox, a graduate of Oberlin. A Republican politician, a good soldier, he proves to be one of the North’s best political generals. Four Union batteries, six guns in each, have neutralized the eight Confederate guns supporting Toombs. Confederate cannon on high ground southeast of Sharpsburg, however, can deliver an oblique fire down the valley of the Antietam.

Union Brig. Gen. Isaac Peace Rodman is a Quaker. He will take his division plus one brigade from the Kanawha Division led by Col. Hugh Ewing and seek to cross at a cattle ford downstream from the lower bridge. Hugh Ewing is a double relative of Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. He is Sherman’s foster brother and also his brother-in-law. He spent two years at West Point before he dropped out. Rodman is guided by a local farmer. But a ford where a farmer can cross cattle and one where Rodman can cross more than 5,000 men and artillery are quite different from one another. It will be noon before Rodman abandons his efforts to cross at the cattle ford and succeeds in crossing the Antietam at Snavely’s Ford.

Meanwhile Burnside’s first attack begins about 9:30 a.m. It is spearheaded by the 11th Connecticut, commanded by Col. Henry Kingsbury, a West Point graduate of the class of 1861. He had been an artillerist, but seeing that you only have limited advancement in the artillery, he switched to infantry and today leads the 11th Connecticut. His men advance and engage in a firefight with the Confederates. A few seek to wade the creek but are gunned down. Kingsbury is not as lucky as John Gordon: He’ll be shot five times, and the fifth wound is fatal.

Toombs’s Georgians are ensconced on the far side of the Antietam and in the woods extending 500 yards south. He also has men up above in a rock quarry. The banks are steep. Remember, if you wade the river think how slippery that steep bank becomes.

Col. George Crook commands the other brigade in the Kanawha Division. Crook is a West Pointer, a good friend of Brig. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. Reaching the Antietam upstream, he fumbles around for about two hours before finally finding a crossing where he gets his men across by dribs and drabs.

Now it’s eleven o’clock. McClellan is getting upset, and a staffer gallops up with another message for Burnside to hurry and get across. Burnside and Cox call for the next try, and this time nobody is going to miss the bridge. A column of two regiments, eight men abreast, will come up that road. These regiments are the Second Maryland and Sixth New Hampshire. Up the Rohersville Road advance the two regiments. On the other side of the Antietam, at a range of 50 to 60 yards, Toombs’s Georgians open fire. To them it’s like a shooting gallery, except the Georgians are playing for blood. Shot to pieces, the two regiments fall back. It’s now twelve o’clock, and still Burnside’s men have not crossed the Antietam. The Yankees advance two 10-pounder Parrott guns manned by Kentuckians to point-blank range of the Confederates. At a range of less than a hundred yards, Union red-legs fire double charges of canister into the brush on the hillside across the creek. Brig. Gen. Samuel G. Sturgis’s division has been committed. Sturgis is another graduate of the West Point class of 1846. He is also colonel of the Seventh U.S. Cavalry Regiment when Lt. Col. George A. Custer leads it to destruction at the Little Bighorn, some 14 years in the future.

Sturgis goes to the commander of his second brigade, Col. Edward Ferrero, and asks for two regiments. Ferrero’s father had been the dancing master at West Point, teaching social graces to the cadets. Ferrero had followed in his father’s footsteps, but he had left that employment to become a power in New York City’s Tammany Hall. He entered the Union Army as colonel of the 51st New York. Ferrero has recently suspended the sutler’s license to vend alcoholic beverages to the men in his brigade. He picks the two regiments ordered to secure the bridge at the point of the bayonet. They are the 51st Pennsylvania commanded by Col. John F. Hartranft and the 51st New York led by Col. Robert Potter. A 51st Pennsylvania corporal, miffed at Ferrero’s support of prohibition, calls, “Will you give us our whiskey, Colonel, if we take it? Colonel, do we get our whiskey?” Ferrero, being a good politician, used to promising everything, responds, “Yes, by God!”

Shown from the Confederate perspective, “Burnside’s Bridge” over Antietam Creek is where Ambrose Burnside sent regiment after regiment across the creek in an attack on Lee’s right flank.

It has been a mistake to send men up the Rohersville Road that parallels the creek’s bank leading to the bridge. So when the two regiments attack, they’re going to form on the reverse side of a ridge that will shield them from Toombs’s riflemen until the last minute. The color companies are aligned to strike the head of the bridge.

At a little after the noon hour the signal goes out to advance. Coming down that slope, eight abreast, the two regiments close on the bridge. Soldiers of the 51st New York veer off to the right to reinforce the 11th Connecticut behind the upstream stone wall. The 51st Pennsylvania along with the New Yorkers’ color guard are the first across the bridge. Worse, if possible, Toombs’s Rebels have learned that Rodman’s men are crossing downstream at Snavely’s Ford and will soon be taking them in the flank and rear. The Yankees are now over the Antietam, but there are more problems. Ferrero and Brig. Gen. James Nagle’s brigades are short of ammunition. There’s another pause of an hour while they recall Sturgis’s men to the east side of the Antietam to refill cartridge boxes. Burnside then pushes Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox’s First Division across. Willcox deploys his men and, when ready to advance, he forms the right of Burnside’s IX Corps.

After a lengthy delay, about 3 p.m., Burnside’s forces attack the Confederates holding the ridge to the west of what forever after will be known as Burnside’s Bridge. They advance toward Sharpsburg, pushing Rebs back into the outskirts of town—Federal soldiers see the church spires ahead. Just before they reach the road to Harpers Ferry, however, General Lee sights Ambrose Powell Hill, adorned in his red battle shirt, leading his Confederates forward to save the day for the Army of Northern Virginia. He had left Harpers Ferry about 6:30 that morning, and his men had been marching hard all day. Hill immediately hurls his 3,000 men at the advancing Federals. James J. Archer’s and Laurance O’Branch’s brigades slam into and maul the Ninth New York, a Zouave regiment. General Rodman is mortally wounded. When Confederate troops under Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg smash into the Federal left, the inexperienced brigade of Col. William Harland breaks. Under increasing Rebel pressure, Cox orders a withdrawal of the IX Corps back to Antietam Creek.

After Burnside is repulsed, his troops fall back into the hollows on the west side of the Antietam. Pulling back into a hollow above the bridge is the 23rd Ohio. Its commander, Rutherford B. Hayes, had been wounded at South Mountain three days previously, so he is not here. William McKinley is. So after the repulse, McKinley, commissary sergeant of the 23rd Ohio, serves the Buckeyes coffee. It’s quite a regiment, with two future Presidents. William Starke Rosecrans had been the original colonel. In it had served a future judge of the Supreme Court, Stanley Matthews.

Union soldiers stand watch over the grave of Federal soldier John Marshall on a hill near the West Woods. More than 23,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured at Antietam.

The final denouement comes later, when Edward Ferrero is promoted to brigadier general. The next time his command is in formation Cpl. Lewis Patterson cries out, “Where’s our whiskey? How about that whiskey?” Remembering his promise, Ferrero rescinds his suspension of the sale of alcoholic beverages.

The day’s final Union surge is checked and turned back by a resolute stand by a handful of Confederates and Hill’s timely arrival. By sundown more than 23,000 Union and Confederate soldiers are casualties in what had become the bloodiest day in American history.

McClellan declined to renew his offensive on the 18th, and Lee remained in position on the blood-soaked battlefield. After a truce to bury the dead and collect the wounded, Lee ordered a withdrawal back across the Potomac, downstream from Shepherdstown. McClellan did not press a pursuit.

While Antietam had not been a complete Federal victory, Lee’s incursion into the North had been decisively turned back. Five days after Antietam, taking advantage of the Union victory, Abraham Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Unless Confederates returned to the Union in the next hundred days, Lincoln announced, he would declare all slaves who resided in areas controlled by the Confederacy free as of January 1, 1863. The war to save the Union was now also the war to free the slaves.