JULY 1–3, 1863

After the Battle of Chancellorsville Robert E. Lee turned back suggestions that he send some of his forces west, or go himself, to relieve Union pressure on Vicksburg and Middle Tennessee, deciding once more to cross the Potomac on a grand raid into Maryland and Pennsylvania. An invasion of the North would allow his men to forage liberally, taking the burden off the wartorn Virginia countryside, and perhaps leading to an opportunity to destroy the Army of the Potomac once and for all. Some observers will later claim that the defeat or destruction of the Army of the Potomac was his chief aim. Certainly a major Confederate victory on northern soil might lead to further demands by antiwar northern Democrats for a negotiated peace.

In addition, Lee and his chief, Jefferson Davis, both hoped that a triumph of Confederate arms would encourage France or Great Britain to recognize the Confederacy and intervene on her behalf. In mid-June the Army of Northern Virginia evacuated its earthworks behind the Rappahannock and slid west, then north, crossed the Blue Ridge, turned down through the Shenandoah Valley, and across the Potomac River. On the way north, Confederate forces captured Winchester and bypassed Harpers Ferry.

It is a restructured army of about 75,000 men that undertakes this invasion. After the death of Stonewall Jackson, Lee reorganizes his army into three infantry corps. James Longstreet will continue in command of I Corps. Elevated to corps command and recently promoted to the rank of lieutenant general are Richard S. Ewell (II Corps) and A. P. Hill (III Corps). For Ewell, it’s his first combat command in nearly a year, since his wounding in the Second Manassas campaign; Hill, an aggressive division commander, finds that corps command presents new challenges. Moreover, as he moves northward, Lee must contend with cavalry commander Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart, whose ego is bruised after the Union cavalry embarrassed him in a pitched action at Brandy Station, the war’s largest cavalry battle, on the eve of this campaign.

In the aftermath of Chancellorsville, the Union Army of the Potomac takes stock of itself. Regiments that had enlisted in 1861 reach the end of their service obligation and return home. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker contemplates responding to Lee’s northward shift by striking at Richmond, but instead shields Washington from the invaders and feuds with General in Chief Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck about who should control various detachments. By the last week of June, President Lincoln has heard enough, and when Hooker offers his resignation, Lincoln selects Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, the commander of V Corps, as Hooker’s replacement. Meade will have to take control of the army as he maneuvers against Lee.

On June 19, Ewell’s vanguard begins to ford the Potomac River at Williamsport, and joined by the rest of the corps, crosses into Pennsylvania on the 22nd and occupies Chambersburg. Hill’s and Longstreet’s corps cross the Potomac on June 24 and 25, the former near Shepherdstown and the latter at Williamsport. Lee sends Jeb Stuart and three brigades of his cavalry to bypass the Army of the Potomac to the east and carry out “all the damage you can.” Ewell’s orders are to press on toward the Susquehanna River and Harrisburg and capture the state capital if possible. By the 27th the remainder of the Army of Northern Virginia is concentrated around Chambersburg.

Lee does not learn that the Army of the Potomac is north of the Potomac River until the night of June 28–29. He also soon finds out that the Union Army has a new commander, George G. Meade. Lee decides it’s time to seek battle, and so he sends orders for his army to concentrate on Cashtown Gap, west of Gettysburg. By the evening of the 30th, he’s with Longstreet’s I Corps at Chambersburg, just behind A. P. Hill’s III Corps at Cashtown. Just below the Susquehanna River, north of Gettysburg, is Richard Ewell’s II Corps, stretched out between Carlisle and to the east of York. Remember, Lee doesn’t begin to concentrate his army until the morning of June 29. It’s a long way—35 miles up to Carlisle—to let Ewell know, and more than 50 miles over to York to apprise Early. The couriers carrying these messages are going to be pounding along on their horses. It’s going to be late in the day on June 29 or in the early morning of June 30 before two of Lee’s three corps commanders get their people in motion. Moreover, Lee doesn’t know where the Yankees are, because Jeb Stuart is out of contact, having decided to ride around the Army of the Potomac, only to find that the Union Army is blocking his route of return.

Meade, after taking a day to get his bearings on June 28, moves up rapidly to take position to cover Washington and Baltimore and search for the enemy. He had accepted his new command reluctantly. He writes his wife that night and says, “I have been sentenced and convicted without a trial.” It is an awesome responsibility that he assumes. Meade takes stock of his new command on June 28 and tries to appoint his own chief of staff, but three generals turn him down, and he’s stuck with Hooker’s man, Maj. Gen. Daniel Butterfield.

Heretofore, it was the Union leaders that had failed their men. This had led Lee to believe his army was invincible without realizing that extenuating circumstances made them superior, especially the awe in which the Union leadership held the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and General Lee. One-third of the Union Army is from Pennsylvania. On the morning of June 30, men in I Corps, which has many Pennsylvania units in it, unfurl their colors. The bands break out their instruments and play as they cross into Pennsylvania. Down in Virginia women seemed of dour face and scowled. Up here they cheer and greet the soldiers. When they go by the convent at Emmitsburg, the nuns stand by the roadside ladling out buttermilk and water to the troops.

Despite his misgivings, Maj. Gen. George Meade took command of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, 1863, less than one week before Confederate forces would converge on Gettysburg.

Lee does not want to fight a battle until his army is concentrated. Brig. Gen. J. Johnston Pettigrew takes his men forward from Cashtown to reconnoiter Gettysburg on June 30. Here they spot Union cavalry. Brig. Gen. John Buford, in command of the Union cavalry forces there, observes Pettigrew’s men. Pettigrew comes back and reports what he’s found. A. P. Hill makes a vital but flawed command decision: Instead of a brigade he will send two divisions to Gettysburg to find out who is there. I will argue that that’s the worst decision any Confederate commander will make at Gettysburg. Lee prefers not to fight a battle until his army is concentrated, but Hill takes it upon himself to send out two divisions. In the lead will be the division headed by Maj. Gen. Henry W. “Harry” Heth, the bottom of the West Point class of 1847, supported by Maj. William “Willie” Pegram’s battalion of artillery, to be followed up by Maj. Gen. William Dorsey Pender’s division—a force of more than 14,000 sent to find out what and who is in Gettysburg.

Back in Gettysburg, Gen. John Buford and two brigades of cavalry await the Confederate advance. Heading north toward Gettysburg is Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds’s I Corps; not far behind is Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps. Buford will try to buy time for the infantry to arrive. He sends one brigade north of town to watch for Ewell, while a second brigade advances west along the Chambersburg Pike and throws out pickets to watch the roads north and west of Gettysburg.

Buford plans to fight for time to delay the Confederates. South of Gettysburg is Cemetery Hill and Cemetery Ridge, good terrain to hold if the Union opts to fight a battle here. His men move out about 5:15 a.m. on July 1. The Confederates are going to have to use artillery to support their skirmishers when they run into the Union cavalry. Buford’s defense in depth buys time for the arrival of Reynolds’s command. Buford forces the Confederates to burn up two hours before they even come within clear view of Seminary Ridge, west of Gettysburg. Buford is a West Pointer, class of 1848, one year behind his initial adversary, Harry Heth.

Buford establishes his main line of defense along McPherson’s Ridge, a mile west of Gettysburg. Although he has 1,200 men, one-fourth of them are detailed as horse holders. Fighting dismounted, armed with single-shot breech-loading carbines, Buford’s men pop away, supported by an artillery battery. Heth’s Confederates form into battle line to the west along Herr Ridge and advance eastward across Willoughby Run. They aren’t quite sure what’s ahead of them, and they have no way of finding out short of fighting. North of the Chambersburg Pike and the unfinished railroad grade, Brig. Gen. Joseph R. Davis, nephew of the Confederate president, deploys three regiments: the 42nd Mississippi, 2nd Mississippi, and 55th North Carolina. Brig. Gen. James J. Archer forms his brigade on the south side of the road. From right to left, he deploys the 13th Alabama, 1st, 14th, and Seventh Tennessee; the Fifth Alabama fans out as skirmishers.

On the first day of the battle, Federal I Corps troops under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds blocked A. P. Hill’s attacking Confederates in the fields and woodlands of McPherson’s Ridge.

If it looks like it’s going to be Yankee cavalry versus Rebel infantry, it won’t be that way for long. John Reynolds sets the I Corps on the road early in the morning. As he approaches Gettysburg from the south, Reynolds, riding with his staff up Emmitsburg Road, passes Big Round Top, Little Round Top, and Cemetery Hill, deciding the last is the best artillery position in the area. This is something Reynolds, a West Pointer, class of 1841, and an artillerist himself, can appreciate. He hears the firing of the artillery, “Boom, Boom!” He puts his staff officers to work tearing down the west fence alongside the road and then rides a short distance west across the fields toward Seminary Ridge, named for the local Lutheran Seminary perched on top. He looks up at the building’s cupola, spots Buford, and asks what’s going on. Buford replies, “The devil’s to pay.”

Reynolds evaluates the situation out front; he sees the Confederates, and he makes a decision. Can Buford hold on a while longer? Buford says he can. Reynolds sends two messages. One goes to Howard, directing Howard to close up. The other goes to Meade. Reynolds reports that the enemy is advancing in heavy force, and Gettysburg is a good place to fight a battle. He plans to hold this ground, and if driven from it, he’ll fall back and barricade the streets of the town. He then returns to the Emmitsburg Road, where he’ll meet the vanguard of Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth’s First Division. He tells Wadsworth to hurry his men forward. He then rides back to the seminary to oversee the relief of Buford’s men by the infantry. Buford’s horse soldiers have accomplished their mission. They’ve held up the enemy for three hours.

Leading the way is Wadsworth’s division. James Wadsworth is one of the wealthiest men in the United States. He had run as a Republican for governor of New York in 1862 and lost. In front is Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler’s Second Brigade, including the 76th New York, 56th Pennsylvania, and 147th New York. They’ll take position north of a railroad cut just beyond the Chambersburg Pike. Moving into position south of the road are Cutler’s 95th New York and the redlegged devils of the 84th New York—or, as they preferred to be called, the 14th Brooklyn.

The Confederates press forward. They are about to overlap Cutler’s left. Reynolds hurries over and spots Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith’s “Iron Brigade” arriving: They have a band with them playing “The Campbells Are Coming.” He directs them into line, and as he turns around, he’s hit by a bullet behind the ear and is killed instantly. As his aides loosen his collar, they find two Catholic medallions hung around his neck. This is surprising because he is not Catholic, and none of them knows that he is seriously interested in any woman.

They carry Reynolds’s body to the rear, with instructions to send it to his home in Lancaster after it is laid out in Philadelphia. And as they’re laying him out on July 4, with his sisters there, a lady comes in. She is Katherine “Kate” May Hewitt. Kate has his West Point ring, and tells his sisters that they met on a boat from California to New York and that they’re engaged. Reynolds was a Protestant, she a Catholic. That is why he had not told his family. The two agreed that if he was killed and they couldn’t marry, she would join a convent. After he’s buried, she will travel to Emmitsburg and join the St. Joseph Central House of the Order of the Daughters of Charity—the same order that had greeted the I Corps along its line of march the previous day.

With Reynolds’s death, Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday finds himself in command of I Corps and all the troops on the field. He needs help. Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard arrives well in advance of his XI Corps, and goes up to Fahnestock’s Observatory. About the time he arrives, the Union position north of the Chambersburg Pike collapses. The Confederates overlap the Union right wing by a considerable distance. The Confederate regiments are much larger—most of them far larger than I Corps regiments. The 55th North Carolina far overlaps the Union right, which causes the 76th New York and the 56th Pennsylvania to pull back onto Oak Ridge, leaving the 147th New York to fend for itself. The Confederates sweep around the New Yorkers’ right flank. Their commander, Lt. Col. Francis C. Miller, is ready to give the command to retreat and he’s wounded. Somebody yells, “Break for the rear,” and the regiment breaks, and some of them flee into the streets of Gettysburg, arriving just as Howard enters the borough.

On the morning of July 1, two divisions of Confederates advanced to drive Federal cavalry from the town of Gettysburg. Against stiff resistance the Confederates pressed forward only to encounter infantry of the Federal I Corps, who drove the Rebels back from McPherson’s Ridge. Other I Corps troops deployed west of Gettysburg, while the XI Corps moved into position north of the town. At noon part of Ewell’s corps attacked the I Corps right; by afternoon the battle spread north of town, where Early’s Confederates smashed into the XI Corps flank. At the same time, afresh Confederate division attacked the I Corps on Seminary Ridge. By 4 p.m. the Federals retreated through Gettysburg to take positions on the high ground south of town.

Howard decides to contact Meade, telling him, “Reynolds is dead. The I Corps has fled at the first shot,” for which Doubleday never forgives him. I don’t think anyone of I Corps forgave him either. Howard’s messenger traveled almost as fast as Reynolds’s to army headquarters at Taneytown. Reynolds’s message arrives first. Meade reads it and he feels good about it. He likes the upbeat tone of Reynolds’s message: “Just like Reynolds,” he says to his staff. Within a half hour he reads Howard’s harbinger of doom, reporting that Reynolds is dead and I Corps has fled at the first shot.

Meade knows that there’s favorable ground near Gettysburg where the Union could accept battle, because Reynolds has told him so. He can’t go to Gettysburg himself: He wants to wait for more information. So he turns to my “real hero of Gettysburg,” Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock. Hancock’s beginning to lose the “battle of the bulge.” Charismatic, six feet two, a clean white shirt every day, and a booming voice. Meade tells Hancock to go to Gettysburg, make an estimate of the situation, and advise as to whether this is where Meade should concentrate and give battle. Hancock climbs into an ambulance, spreads out his maps, and heads to Gettysburg.

Back at Gettysburg, things do not look good for the Yankees. Joe Davis’s brigade is bearing down on the Union right flank, driving the 147th New York before it. South of the Chambersburg Pike, James Archer’s men are pressing forward.

Archer is a cocky guy who was warned by Pettigrew to advance cautiously, but he does not. He’s a Princeton man, not a West Pointer, but he is an old Army man who entered the military from civilian life. And he is going to be assisted initially by Davis’s success. With the collapse of the Yankee line north of the railroad grade and the withdrawal of supporting artillery, the Federal regiments south of the pike are in a bad way with Rebels coming from two directions. Archer’s people look up toward Seminary Ridge. The Iron Brigade has arrived on the field. Coming up in columns as they begin to deploy in line are soldiers in black hats. These Black Hats are the 2nd, and 7th Wisconsin and the 19th Indiana, joined by a new regiment, the 24th Michigan. The Confederates suddenly realize they aren’t facing local militia; they are confronting the Iron Brigade.

The Yankees now overlap the Rebel right flank in the wooded area south of Herbst Woods and double them up like a jackknife. Alabamians and Tennesseeans flee. Pvt. Patrick Murphy of the Second Wisconsin is faster than poor James J. Archer: Murphy horsecollars him, and Archer has the privilege of boasting to his friends, I’m the first Confederate general captured in action since Bobby Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Doubleday encounters him: they knew each other in the prewar army. Doubleday runs up and sticks out his hand: Archer, damn glad to see you. Archer snaps back, Goddamn it, I’m not glad to see you. The Iron Brigade chases Archer’s Rebels all the way back to and across Willoughby Run.

As the Iron Brigade drives back Archer, the attention of the Union forces shifts north across the Chambersburg Pike, where Joe Davis’s brigade is bearing down on the unfinished railroad cut.

Davis has the ideal moment to strike what could be a fatal blow to Wadsworth’s division. In my view, an experienced commander would have followed up on his initial success. As Davis advances he comes under fire. You remember the last time we saw the 14th Brooklyn, those “redlegged devils” and the 95th New York were facing west on West McPherson’s Ridge. They’ve shifted position and are now behind a post-and-rail fence on the south side of the Chambersburg Pike fronting north. Not having reconnoitered the ground to his front, Davis orders a left wheel. That means the right-most soldier in the 42nd Mississippi will mark time, and every man to his left, shoulder to shoulder, will start turning like a door swinging open.

This is bad for the Second Mississippi because they are going to come up on this deep railroad cut. They are not going to know how deep this cut is until too late. The 55th North Carolina is not initially in big trouble because they are not going into the deep cut. Nor is the 42nd Mississippi. But for the Second Mississippi the cut is so deep and steep that a soldier can’t fire out of it. It shows poor judgment on the part of Davis. Meanwhile, the two New York regiments are reinforced. Coming out of the edge of the timber at the seminary is the reserve regiment of the Iron Brigade, the Sixth Wisconsin under Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes. In addition to their 350 men, they have picked up the brigade guard, another hundred soldiers. Dawes takes position on the right of the 95th New York. Then the Yankees charge.

The Second Mississippi has no firebase. The people on their left—the 55th North Carolina—and right—the 42nd Mississippi—have a firebase but the people in the center are not firing. That means they had better get out of here. They’re going to leave the Second Mississippi “holding the bag.” Soon one of Lt. John H. Calef’s guns, belonging to Company A, Second U.S. Artillery, is positioned and firing down the cut. Would you like to be in that railroad cut with a bunch of Yankees firing down on you? What are the Rebs going to do? They surrender. The Yankees capture more than 200, and Cpl. Francis Waller of the Sixth Wisconsin captures the Second Mississippi’s colors. Dawes will later say that he had so many surrendered sabers he couldn’t carry all of them in his arms.

Shortly after 11 a.m. on July 1 a lull settles over the battlefield. Even as the Union forces celebrate their victory in the railroad cut, more Confederates arrive on the field. This time it’s the lead division of Richard Ewell’s corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes. They come from the north; Rodes observes the action in front of him from Oak Hill, a wooded area some distance to the north of the railroad cut.

Imagine what Robert Rodes and Dick Ewell think when they arrive here about noon. They see the entire battlefield in front of them. They look out and recognize that they have a splendid opportunity to strike the Union I Corps in the flank. There are no Union troops within hundreds of yards of them. So, without coordinating their movements what do they do? They order up two batteries of artillery, put them in position, and open fire, drawing to themselves the Yankees’ attention.

Rodes’s Confederates are to attack around 2:30 p.m., but it’s not going to be coordinated. Brigade commander Col. Edward A. O’Neal advances first with three of his five Alabama regiments, not his full strength. They advance southward along the eastern slope of Oak Ridge, come under fire, and break. Next comes Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson’s four Tarheel regiments. They form in the low ground fronting the Forney Farm; they head southeast toward what they believe is the Union right in Wills Woods thrusting westward of Oak Ridge.

The problem with Alfred Iverson: He is a Georgian. According to Confederate law, if a brigade is composed entirely of regiments from one state it should be commanded by someone from that state. There is no doubt that these are all North Carolinians being led by this Georgia boy. He is not a West Pointer; he’s gone into the Army from civilian life. He’s the son of a former Georgia congressman. He has served in the elite First U.S. Cavalry. Iverson gives them a good fighting speech and away they go, toward the Union right … or so they think.

Brig. Gen. Henry Baxter’s Federal brigade had reached Oak Ridge earlier and taken position on the right of I Corps, initially fronting the Mummasburg Road. From here, sheltered by a stone wall, they had savaged O’Neal’s Alabamians. When they see Iverson’s men come into view, Baxter redeploys his people at a right angle to the Mummasburg Road, behind another stone wall. Iverson’s men are unaware of their presence. Baxter’s front, the second rank-and-file closers, lie down and watch the Confederates come across the field. As the North Carolinians approach, the regiment on the left, the Fifth North Carolina, is closest to the Yankees. The 20th, 23rd, and 12th North Carolina extend the line south-westward—you want to be in the 12th. When the Confederates approach to within 50 yards of the Yankees, Baxter orders his men to fire. Rank after rank stands up and unleashes a deadly volley; then the bluecoats charge, capturing flags and taking prisoners as they go. Rebels wave white shirts or bandanas in an effort to surrender.

Back at the Forney Farm, adjacent to Oak Hill, Iverson shouts that his men are mutinying and going over to the enemy. His North Carolinians are repulsed with the loss of more than 500 men, 62 percent of their strength. A soldier later writes, “The widows and orphans of North Carolina from Piedmont to Tidewater must rue the rashness of that hour.” Iverson’s command is obliterated. His men are buried where they fall, including a group of bodies heel to heel. To this day some people claim this ground, known as Iverson’s pits, is haunted.

Their ammunition exhausted, Baxter’s brigade is relieved by Brig. Gen. Gabriel René Paul’s brigade. Paul will be wounded and blinded for life in the desperate fighting here. The XI Corps’ position to the northeast comes under severe pressure. Following a botched attack by Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel, the Confederates re-form and come at the Federals from two directions: Brig Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur’s Tarheels from the north, and Daniel’s from the west. Paul’s brigade breaks: One regiment, the 16th Maine, stands fast to allow the others to escape. When the Maine regiment’s colonel, Charles W. Tilden, sees time running out, he drives his sword into the ground and breaks it off at the hilt. His men tear up their colors as they retreat.

Earlier that day, as the Union XI Corps deployed two divisions north of Gettysburg, division commander Francis C. Barlow, seeing a rise in front of him, advanced his command to what will become known as Barlow’s Knoll. It’s higher ground, to be sure, but in moving forward Barlow loses contact with the remainder of the Union line. Moreover, he’s so busy watching the Confederates to the northwest that he fails to be as observant about a new threat approaching from the northeast along the Harrisburg Road.

You will find on Barlow’s Knoll that the ground to the north falls away quickly into Rock Creek, offering good cover to forces advancing from the north and northeast. In possession of the ground to the northwest are skirmishers from Confederate Brig. Gen. George Doles’s Georgia Brigade—one of Rodes’s five brigades. Barlow anchors his position with four guns of Lt. Bayard Wilkeson’s Company G, Fourth U.S. Artillery, and the 17th Connecticut; he deploys three regiments around the knoll to the north and on each flank. There they are, when from the northeast, marching along the Harrisburg Road, approaches the division led by Lee’s bad old man, Jubal Early. He has his artillery chief, Lt. Col. Hilary P. Jones, unlimber 16 guns north of Rock Creek. They blast away at Wilkeson’s battery, wounding Wilkeson in the leg and knocking out his battery. Meanwhile, John B. Gordon leads his brigade forward. He’d been badly wounded at Antietam as colonel of the Sixth Alabama defending the Sunken Road. When he establishes contact with Doles’s left, they’re ready to attack. They will be joined by Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays’s Louisiana Tigers bearing down on the knoll from the northeast. You’ve got Gordon with his six Georgia regiments hammering Barlow’s front, George Doles on his left, and Hays enveloping his right. Barlow’s position collapses.

After the war Gordon spends much time preaching sectional reconciliation. He tells people that he came upon a badly wounded Barlow, who asks Gordon to send a message to his wife. Gordon agrees, and orders a soldier to look after Barlow. Then he rides away, thinking Barlow’s a goner. In the meantime, a Confederate cavalry general, James Byron Gordon, had perished on the field of battle, so the story goes. Barlow thought that was the Gordon who had helped him. Years later Gordon encounters Barlow at a dinner party. Thus the two men meet, each thinking the other’s dead, and they greet each other heartily—or so Gordon tells the story. Gordon forgets that they are both at Appomattox Court House and then embarked on public careers. Still, it makes for the sort of story people want to believe.

Wilkeson’s fate offers a better story. His father Samuel is a newspaperman, representing the New York Times. He is with the army. This is going to be unfortunate for Meade, because the elder Wilkeson believes that his son’s battery is placed too far out in front. When a shell explodes near the battery it all but severs the younger Wilkeson’s right leg. The only thing that is holding his right leg to the rest of his body are the tendons. Wilkeson uses his pocketknife to amputate his lower leg—a personal amputation, and because of it he dies. Meade has made an enemy who will subsequently use his newspaper to unfairly criticize Meade.

As the Confederates swarm over Barlow’s Knoll, the Union XI Corps breaks. It’s about 4:30 p.m., and the corps retreats southward through Gettysburg. About that same time the Union I Corps also breaks, pulling back off Seminary Ridge and scampering through the streets of the town. As the Yankees rally on Cemetery Hill, just south of Gettysburg, the Confederates deliberate whether to launch another attack. As the XI Corps retreats, one Federal brigade, just north of town, attempts to check the advancing Confederates.

Popular legend blames Lt. Gen. Richard “Old Baldy” Ewell for Confederate defeat at Gettysburg due to his failure to carry out Lee’s order to secure Cemetery Hill; a direct order was likely never issued.

In response to orders from General Howard, Second Division commander Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr contacts one of his brigade commanders, Col. Charles R. Coster, and says, “I want you to advance your brigade from East Cemetery Hill down into town and cover our retreat.” As Coster approaches the “Diamond” (the term mid-19th-century residents of south-central Pennsylvania called the town square), he detaches the 73rd Pennsylvania. Coster advances his other three regiments, the 27th Pennsylvania, 154th New York, and 134th New York, and takes position behind a post-and-rail fence at Kuhn’s Brickyard. Two Confederate brigades—Hays’s and Avery’s—charge, and after perhaps ten minutes Coster’s men have had enough. They are driven through the town, a large number of them captured.

After the battle, on July 4, they’re going to find an unidentified dead Union sergeant clutching an image of his three children. Newspapers publish the story and others circulate engravings made of the three adorable children. Finally, Philinda Humiston of Portville, New York, recognizes the faces as her children: The dead soldier was her husband Amos, of the 154th New York. The incident touched many hearts and led to fund-raising to establish an orphanage for children of the Union dead in Gettysburg, where the the Widow Humiston would later work. It opened in 1866; it’s located on Cemetery Hill along the Baltimore Turnpike.

On Cemetery Hill, General Howard struggled ineffectively to reorganize the shattered Federal forces. When Winfield Scott Hancock arrived with orders from Meade to assess the situation, he displaced Howard and set about organizing a defense. By late afternoon, with the Federals falling back in disarray, it was time for the Confederates to decide whether to follow up on their previous successes.

Dick Ewell is trying to figure out what is going on. He informs Lee that he’s willing to contemplate an attack. He can’t form his command up in the streets of the town itself, he’s got to deploy them east of the borough. He’d like to wait for the arrival of his third division under Maj. Gen. Edward “Old Allegheny” Johnson before attacking; he tells Lee, “I will attack if you will release to me Richard Anderson’s division,” which has just arrived west of town along the Chambersburg Pike. Lee responds, “No, no, I am not going to release Anderson. I have to keep him in reserve lest we face disaster here.”

Notice that uncertainty in Lee’s response? If you’re Ewell, you are used to the vocal nuances of your commanding officer. What is Ewell to do? Unlike Stonewall Jackson, under whom Ewell had served as a division commander in 1862, Lee has given him a discretionary order twice repeated. You will exercise the discretion given to you, and that’s what Ewell did. He decides he isn’t going to attack and seize Culp’s Hill on the evening of the first. Late that night a Confederate reconnaissance discovers that Union forces have occupied Culp’s Hill.

Thus ended the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg. In future years Ewell will come under criticism for not attacking Cemetery Hill: His decision not to attack becomes one of the many what-ifs of the battle.

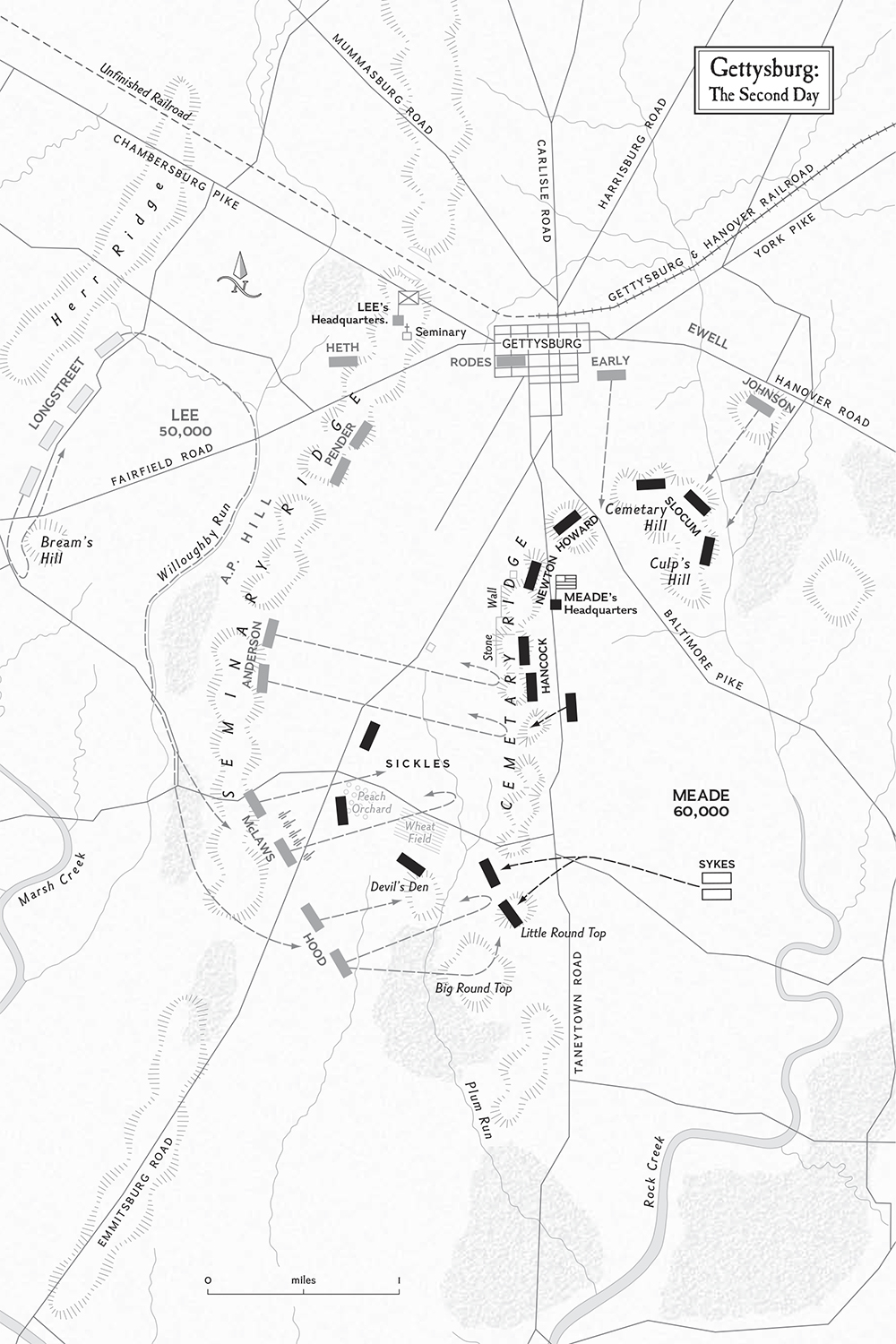

All through the night and into the next morning Union reinforcements arrive south of Gettysburg. They take up a line that resembles a fishhook, with the barb at Culp’s Hill, the curve draped along Cemetery Hill, and the shank extending southward along Cemetery Ridge toward Little Round Top. By mid-morning the VI Corps has yet to arrive, and they are scheduled to appear during the day.

At his headquarters on Seminary Ridge, in the early morning hours of July 2, Robert E. Lee sets about making plans to renew his offensive.

Lee and Longstreet are in disagreement on what the Confederates should do. Longstreet believes that it would be best if the Confederates forced the Yankees to do the attacking: He remembers Fredericksburg. Lee, on the other hand, is anxious to attack: He remembers Chancellorsville. Lee finally breaks off the discussion, saying, “The enemy is there, and I am going to attack him.” Longstreet responds, “If he is there in the morning that means he wants you to attack him—a good reason for not doing so.” To which Lee replies, “I am going to whip them, or they are going to whip me.”

Lee orders a reconnaissance of the Union left. He calls for Capt. Sam Johnston, the army’s chief engineer. Lee tells Johnston, “I want you to take an escort with you and make a reconnaissance and see how far south on Cemetery Ridge the Union line extends. I want you to go up on the high ground.” Johnston, accompanied by Maj. John J. Clarke of Longstreet’s staff, makes his reconnaissance, and he sees that the Union line does not extend very far south (only to about the site of today’s Pennsylvania State Monument). He’s back about 8:30 a.m. and makes his report to Lee and Longstreet.

Trusted adviser to Lee, Gen. James Longstreet (pictured in a postwar photograph) directed most of the fighting on the second day, recognizing the key strategic importance of Big and Little Round Tops.

Lee decides to order Longstreet to march his two divisions to a position along the Emmitsburg Road, deploy astride that road, and assail the Union left flank. At the same time, Ewell’s corps will launch an assault on the Federal right at Culp’s Hill. It will be Chancellorsville all over again, he believes. Longstreet tells Lee that he is missing one of his eight brigades—Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s—and that he does not want to move out until Law joins. Lee gives him permission to wait for Law.

Now, where does Law have to march from? He has to come from New Guilford, Pennsylvania, more than 20 miles away. His men have been on the march since 2 a.m. After Law arrives, Lee envisions an attack unfolding from right to left, with the divisions of Maj. Gens. John B. Hood and Lafayette McLaws being joined by several of A. P. Hill’s III Corps brigades, commencing with Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s men. What kind of cooperation will there be between Hill and Longstreet? What is Anderson to do? If Anderson is to cooperate, is Anderson under Longstreet’s command? Is Anderson under Hill? It’s never spelled out who controls Anderson.

Anderson uses Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s big Alabama Brigade to extend southward along Seminary Ridge, opposite and more or less parallel to the Union positions on Cemetery Ridge. They make contact with Berdan’s First U.S. Sharpshooters and the Third Maine in Pitzer’s Woods. There’s a sharp firefight, and Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles learns that there are Confederates in his front, concealed in the woods. Sickles is not going to be hung out to dry in Chancellorsville style, so he begins moving his two III Corps divisions west to cover Emmitsburg Road and the Peach Orchard, leaving Little Round Top unoccupied by combat people. The Union left flank is not going to be where Lee thinks it is.

When Longstreet’s people finally move out it is past noon. McLaws has the lead. The two divisions are supposed to work their way southward along a concealed route blocked from Yankee observation. There are two problems with this plan. First, no one has scouted out a route. Second, in the distance, atop Little Round Top, there is a detachment from the Union signal corps. Those men have a good view of the terrain west of Seminary Ridge; if the Confederate movement is detected, the entire operation may be endangered. As McLaws’s vanguard prepares to cross Bream’s Hill, the lead Confederates see the signal station, and they know that that means the signal station can also see them.

Longstreet calls for a countermarch. The countermarch costs valuable time, and the critics will ask why Longstreet didn’t march all his men the way that Porter Alexander moves the 75 guns, the 150 limbers, and 75 caissons of the artillery—by avoiding crossing Bream’s Hill and going around the hill. Instead, they countermarch, and it is not until 3 p.m. that the head of McLaws’s column approaches Seminary Ridge, where he is to deploy astride the Emmitsburg Road.

Longstreet intends his men to attack in echelon—timing their blows in sequence from right to left. The intent of it is this: You hit first on the enemy’s right. The enemy will shift men to check the attack. Then another advance hits to the left, and they may strike a weak spot. Sooner or later, if the attacker gets the enemy shifting units to the left, the enemy will leave a weak point as it scrambles forces to repel the echelon attacks.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, by the time McLaws and Hood are about to arrive at their jumping-off points, the situation has changed. The III Corps under Sickles was supposed to extend the line of the II Corps south along Cemetery Ridge to the vicinity of Little Round Top. But Sickles does not like his position. To the west he sees high ground, a site that looks ideal for artillery. When news comes back of the clash in Pitzer’s Woods, he decides that if he waits in line he might find himself in trouble. So he advances his men, first to the Trostle Farm several hundred yards to the west, then several hundred yards more to Sherfy’s Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road. Union Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys deploys his division facing west along the Emmitsburg Road. David Birney struggles to cover the area between Trostle Lane and Sherfy’s Peach Orchard and the foot of Little Round Top with three brigades, only to find that his line is divided by woods and farmland, particularly Rose Woods and a wheat field, west of Little Round Top.

Through midday George Gordon Meade appeared to be far more concerned about an assault against his right flank at Culp’s Hill than a blow directed at his left. It is not until after 3 p.m. that he rides out to see what is going on. He is furious. Sickles’s position may have some tactical advantages, but he has detached himself from the rest of the army and left the Round Tops undefended.

Meade held a fishhook-shaped position, with his right on Culp’s Hill, his center along Cemetery Ridge, and his left near the Round Tops. Realizing that Meade’s left was exposed, Lee ordered Longstreet to march south with two divisions to attack the Federal left. Longstreet’s assault struck General Sickles’s III Corps, forcing Meade to reinforce Sickles. After desperate fighting at the Devil’s Den and in the Wheat Field and Peach Orchard, the Federal line collapsed. Earlier the Confederates attacked Little Round Top, where Federal forces arrived in time to block their advance. An attack by Ewell’s corps on Culp’s Hill on the Federal right came too late, and an attempt to storm Cemetery Hill at dusk also failed.

The III Corps moves out 10,000 strong. As they make their final advance up to the Emmitsburg Road and to the Peach Orchard, Winfield Scott Hancock and his staff officers are impressed with the parade-ground precision Humphreys’s men display. Hancock, being the realist that he is, remarks, “Just wait; they are going to come tumbling back much faster than they went out.” Hancock is going to have to sacrifice to save Sickles by feeding in piecemeal five of his ten brigades to try to blunt the Confederate attack. Meade will also have to use three divisions of V Corps as he seeks to stall Longstreet’s savage onslaught.

Longstreet may have been right in saying that the next three hours are going to show the finest fighting we’ve seen any soldiers do. Eleven Confederate brigades are going to beat up 15 Union brigades. It’s going to be one of the few times in the Civil War when the attackers are going to lose fewer men than the defenders. One might even argue that this is the bloodiest single day of combat in the entire war, more so than Antietam, although the casualty returns cited for Gettysburg’s three days are not broken down to enumerate the losses day by day.

The only person who is more surprised than General Meade as to the location of Sickles’s corps is Lafayette McLaws, when he finds out where the Union left is posted. It isn’t where he had been led to believe it would be. The Confederates are operating on out-of-date information. McLaws comes up on Seminary Ridge and sees lots of Yankee infantry and artillery to his front in the Peach Orchard and extending north along the Emmitsburg Road to well beyond the Klingle House. They are not supposed to be there, so he’s got big trouble. McLaws informs Longstreet of the situation.

Over on the far Confederate right flank is John Bell Hood’s division. Holding down its right is Evander Law’s brigade, which has been on the road since 2 a.m.

Hood moves into position, extending southward along the Emmitsburg Road. He doesn’t like his situation. He would like to extend his flank and pass over and south of Big Round Top, a move somewhat like the one Longstreet urged on Lee twice, the previous day and that morning, before he had been overruled. Longstreet comes back short and sharp: “General Lee says we are to attack up the Emmitsburg Road, and we will attack up the Emmitsburg Road.” Hood repeats his request and Longstreet repeats his reply. Hood makes a final appeal, employing a key member of Longstreet’s staff to try to get him to change his mind. For the third time Longstreet points out that “General Lee says we will attack up the Emmitsburg Road.”

Law’s Alabamians will have marched at least 26 miles by the time they get into position. They’re going to have the most difficult assignment of any Confederate unit, because they’re going to be moving the farthest and they will be advancing across the roughest ground. Off to the east are two rocky hills: Big Round Top, 789 feet high and heavily wooded, and Little Round Top, 674 feet high, with its west face cleared. They know that’s where the Union signal station is. Despite the fact that Hood’s request to move to the left has been thrice rejected by Longstreet with a reminder of General Lee’s order that they are to attack up the Emmitsburg Road, several of Hood’s brigades immediately drift over toward the Round Tops and the jumble of boulders at their base called Devil’s Den. Their advance seems as if by design.

A young Confederate soldier lies fallen among the boulders of Devil’s Den.

Even before the Civil War, it was known as Devil’s Den. It was a popular picnic place by day and at night a trysting place. Sickles’s extreme left is here. Capt. James E. Smith unlimbers four cannon of the Fourth New York Battery on Houck’s Ridge extending north from Devil’s Den in support of the Orange Blossoms (the 124th New York). The Federals start off more than holding their own. But two Alabama regiments (the 44th and 48th) rush the 4th Maine, supported on the left by the Mozart Regiment (the 40th New York), as well as the 6th New Jersey and two of Captain Smith’s cannon to the right.

Initially the Yanks check the Rebel surge, but the Alabamians soon prevail. The bluecoats abandon the Slaughter Pen and Devil’s Den. The Triangular Field defended by the Orange Blossoms now becomes the focus of attacks spearheaded by the First Texas and Third Arkansas. Savage combat ebbs and flows as Confederates pour into the Triangular Field from the west. But there are too many Rebels. Four regiments of Georgians, Texans, and Arkansans storm forward and carry the position, capturing three of James Smith’s four guns, and driving the Federals from Houck’s Ridge.

While the fighting rages around Devil’s Den, two of Evander Law’s regiments approach the foot of Big Round Top.

One of Law’s regimental commanders is Col. William C. Oates of the 15th Alabama. He has called for 20 volunteers to take as many canteens as they can and fill them up at a well. The cistern is not functioning, so they have to use the windlass. They fill the canteens, but by the time they return, Oates is gone. They wander around, and the Yankees are going to capture them along with the extra canteens, carrying the water Oates’s people needed that hot July day.

When Oates reaches the summit of Big Round Top, he claims that he can see the Union supply train in the distance. He sends one company off to capture seven nearby wagons. That makes 110 men sent elsewhere as Oates directs the 15th Alabama to descend Big Round Top and head north to Little Round Top. The 47th Alabama follows, but it’s becoming confusing in the woods, and the two brigades—Law’s and Brig. Gen. Jerome “Aunt Polly” Robertson’s Texans—intermingle. Had Hood been there, things might have been different. But he’s down, hit in the left arm by fragments from a bursting shell near the Bushman Barn, and it takes some time to notify Evander Law that he is to take over for the fallen Hood.

While the two Confederate brigades close in on the Round Tops and Devil’s Den, Chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren ascends Little Round Top to take in the situation. Finding the summit unoccupied by combat troops, Warren and his staff begin seeking troops to defend the spot. Off in the distance Warren sees Confederates advancing. There’s no time to lose.

Hastily constructed breastworks protected Federal soldiers from Confederate sharpshooters atop Little Round Top. In the distance, Big Round Top is visible.

Warren and his engineer officers look for men just as elements of Maj. Gen. George Sykes’s V Corps arrive on their march toward the Wheat Field. One aide rides up to Third Brigade commander Col. Strong Vincent, a lawyer, Harvard man, 26 years old. Taking in the situation instantly, Vincent, without waiting for orders, hurries his brigade to the south slope of Little Round Top, and then deploys it. On their right is the 16th Michigan. On their left is the 44th New York; on the New Yorkers’ left is the 83rd Pennsylvania, and on the extreme left is the 20th Maine.

The first Confederate attack is launched against the 16th Michigan, the 44th New York, and the left wing of the 83rd Pennsylvania by three Rebel regiments: the Fourth and Fifth Texas and the Fourth Alabama. They fail and fall back. Fighting is also raging in the Slaughter Pen and Devil’s Den at the foot of Little Round Top. The Confederates come back again and assail Vincent’s three right regiments. They charge up in groups and are repulsed a second time.

By this time the Rebels hold the Slaughter Pen and Devil’s Den. That means they have another regiment—the 48th Alabama—available for their next attack on Little Round Top. The 16th Michigan on the right is running low on ammunition; this time the Rebels roll them back from right to left and rush for the summit. Among the mortally wounded is Strong Vincent. Now arriving, coming in from the northeast, is Patrick O’Rorke’s 140th New York, part of Brig. Gen. Stephen H. Weed’s brigade of V Corps. O’Rorke’s men come up in column. There’s no time to deploy them into line. They charge in column with bayonets. The Rebels seem to be on the verge of crumpling Vincent’s brigade from right to left and seizing Little Round Top.

Why is Paddy O’Rorke here? Warren did not see Vincent deploy, so he hurried down the northern slope of Little Round Top and encountered Weed’s brigade. Warren knew the brigade because once it had been his own. Meeting Paddy O’Rorke, Warren tells him to hasten to Little Round Top. O’Rorke’s a promising officer, top of the June class at West Point in 1861, and he goes off with his 140th New York, leaving his brigade commander to come up with the three other regiments. Warren also calls for Lt. Charles A. Hazlett to bring six guns of his Company D, Fifth U.S. Artillery, to the summit.

Weed has the best last words I’ve ever heard. A Confederate sharpshooter fires, and the bullet hits Weed under his right armpit, emerges through his left armpit, and severs his spine. As he falls he says, “Where is Hazlett?” Weed had once commanded Hazlett’s battery; he wants to see his old comrade one more time. Hazlett goes over, having put his guns in position, and bends over Weed. As he is bending over Weed, a Confederate fires—maybe it’s the same guy—and the bullet strikes Hazlett in the temple. Hazlett bathes Weed in his blood. He’s dead. Now staff officers try to encourage Weed. They tell him that he’s going to recover. And these are his last words: “By tomorrow morning I’m as dead a man as Julius Caesar.” And he will be.

Unlikely hero of Gettsyburg Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain, a college professor with little military training, led the 20th Maine in the defense of Little Round Top.

Even as O’Rorke and Weed secure the southwest approach to Little Round Top’s crest, along the left front of Vincent’s brigade, there’s a new threat. Col. William Oates’s 15th Alabama, supported by the 47th Alabama, is about to head straight for Col. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain’s 20th Maine, which forms the far left not only of Vincent’s brigade on Little Round Top but of the entire Army of the Potomac.

Initially Chamberlain deploys in a straight line extending into the woods on the left of the 83rd Pennsylvania. He sends off Capt. Walter R. Morrill with Company B to check out the area to the southeast. Chamberlain later remembers that he’s in position about ten minutes before the Rebels come. The Maine men repulse the first attack; then Oates and his Alabamians begin to work their way around the open Union flank. Oates pushes the 20th Maine’s left flank back; Chamberlain extends his line as well. Before long the line has been bent back until it resembles a V. If Oates can close that V, that’s the end of the 20th Maine and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.

It’s been a long, hard, hot fight. Both regiments, as well as the 47th Alabama, are approaching the breaking point. The 20th Maine has probably marched seven miles this day. The 15th Alabama has already marched 26 miles. They’ve been going over more rugged terrain, and they’ve gone without water. So just as Oates attacks again, Chamberlain orders his men to fix bayonets and to sweep down on the Confederates like a door swinging open on their left flank. His men have the same idea, and just as the Alabamians pause, here come the Maine men, bayonets glistening, charging down. As the Confederates retreat, the boys from Company B, along with a score of the Second U.S. Sharpshooters, pepper their flank. Little Round Top is secure, and Chamberlain becomes a hero.

To the north of Devil’s Den and west of Little Round Top is a wheat field bounded on four sides by woods. There’s only one III Corps Union brigade available to hold the area; several Confederate brigades head toward it from the south and the west. In response, units from the Union II and V Corps arrive as reinforcements and will participate in some of the war’s most confusing and bitter fighting, in an area that will eventually be known simply as the Wheat Field.

At the beginning of the action, there are only two Union regiments in place, because several others had been sent off to fight in Devil’s Den. Men of the 17th Maine, part of Col. P. Regis de Trobriand’s Third Brigade of III Corps, know they’re good, because they had received their diamond-shaped red corps badges before most other units. They are posted along and behind a stone wall. To their right is the 110th Pennsylvania; the other Yankee regiments are west of the Wheat Field on Stony Hill. There’s a six-gun battery in support. Initially they’re going to face an attack into this area by the Third Arkansas and the First Texas. The 17th Maine stands tall. They’re behind a stone wall. It’s going to give them a distinct advantage against the first assault, and they will repulse that. With the Confederate attack stalled, the Confederates commit a fresh brigade—Brig. Gen. George T. “Tige” Anderson’s Georgians. The 17th Maine begins to give way.

Learning of the deteriorating situation, Winfield Scott Hancock rushes reinforcements to bolster Sickles’s people in the struggle for the Wheat Field and Stony Hill. He commits Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell’s four-brigade division, including the Irish Brigade. Two divisions of V Corps, each minus a brigade (those of Vincent and Weed), appear as well. At the head of one of Caldwell’s brigades is Col. Edward Cross. He’s 31 years old. As we know, he has very little hair on the top of his head, and usually covers it with a red bandana. But on this day when he reaches for his bandana, it is black, which Cross reads as an omen. A veteran of the Mexican army, Cross has been wounded at Seven Pines, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. Hancock likes him. Hancock says, “This is your last battle without a star.” Cross simply replies, “Too late, General, this is my last battle.” And it was. To the west two more brigades, including the Irish Brigade, are committed to battle. Before the Irish Brigade advances, they kneel in front of Father William Corby, who grants them absolution before warning them that being cowards in the face of the enemy will deny them a Christian burial. No matter how many Yankees come into the Wheat Field, no matter how many times they drive the Confederates out, the Confederates come back for more. By 6:30 p.m. they finally gain control of the field, which has become a maelstrom of death and destruction.

There has been savage fighting here, with nine Union brigades chewed up. Longstreet has committed two regiments of Robertson’s brigade, one of Brig. Gen. Henry L. “Rock” Benning’s brigade, Tige Anderson’s Georgia Brigade, Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s brigade, Brig. Gen. Paul Semmes’s brigade, and finally Brig. Gen. William T. Wofford’s brigade.

To the west of the Wheat Field, across the Rose Farm, is a peach orchard. The apex of Sickles’s salient is found there in an area where artillery batteries make up for the lack of infantry. Even as Hood’s division sweeps south of this position, Lafayette McLaws’s division prepares to strike it.

It’s 5:15 or 5:20 p.m. before McLaws sends in his first brigade. Out from the cover of the trees on Seminary Ridge emerge Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolinians. They head for Rose Woods and the Wheat Field before they come under fire. Two regiments and a battalion break off from Kershaw’s force and advance toward the Peach Orchard. Union infantry take position to check Kershaw’s advance. Next out of the woods comes Paul Semmes’s Georgia Brigade, and it fights its way into Rose Woods.

Meanwhile Brig. Gen. William Barksdale, in charge of a brigade of Mississippians, itches to get into action. He’s a fire-eater, a former congressman, who back in 1858 got into a fistfight on the floor of the House with fellow Representative Galusha Grow of Pennsylvania. Elihu Washburne, Cadwallader Washburn, and John Potter, joined Grow in pummeling Barksdale. Potter sucker punched Barksdale from the rear, sending Barksdale and his toupee reeling. Barksdale forgot all about Grow and got down on the floor to search for his rug. Today Barksdale goes to McLaws not once but twice, “Are you ready for me to advance?” He has 1,700 Mississippians.

The third time he pesters McLaws, McLaws looks at Longstreet, who nods his head. Barksdale rides back and takes position between the 13th Mississippi and the 17th Mississippi. He orders his men to load and cap their pieces: They’re going to double-time. They’re going to come across that field as fast as they can, going on the presumption that if they cross that ground fast and with “the big momentum behind them,” they will smash through the Yankees. And they do. Brig. Gen. Charles K. Graham and 700 men will ground their arms and surrender. The Confederates finally score a major breakthrough: They have shattered Sickles’s angle. The Union batteries better get out of here fast. Meanwhile, three of Barksdale’s regiments—the 13th, 17th, and 18th Mississippi—pivot to the left and open fire on the left flank of Andrew Humphreys’s division. They are joined by Cadmus Wilcox’s brigade, which surges out of Pitzer’s Woods and closes on Humphreys’s front.

Back by the Trostle Barn, Daniel Sickles watches his corps disintegrate. A cannonball strikes him in the right leg, midway between knee and ankle. They place him on a stretcher and begin to move him off the field. In an effort to reassure his men, he waves a cigar in the air.

Other Union soldiers soon follow. Capt. John Bigelow of the Ninth Massachusetts Battery, seeing his horses go down, orders his cannon to retire by prolonge—a tow rope used to attach a gun to its limber while it remains in firing position. Continuing to blast away, the men use the recoil to retire the guns in stages. That works fine until they reach a stone fence, where their route of retreat is choked off by a too narrow gap in the fence. Bigelow falls wounded; it’s up to his bugler to rescue him from capture. His men save only one gun, but Bigelow has bought precious time by delaying Barksdale. More artillery unlimbers to the east of the Trostle Farm, waiting to hammer the advancing soldiers of the 21st Mississippi.

Andrew Humphreys’s division gives ground. Humphreys seems to be everywhere. He later asserts that his men re-formed six times, and each time the Rebels break his line. When he finally rallies his division he can find fewer than 500 men, having started with well over 4,000. Barksdale and Wilcox have done well. They have smashed through Sickles’s line. They now head for the thinly held Union center.

Awaiting them is Hancock “The Superb,” who today of all days will more than live up to his nom de guerre. He sees Wilcox coming. He also sees the First Minnesota Infantry—262 men. Hancock rides up to Col. William Colvill and tells him that he wants Colvill to charge. Colvill sees that Wilcox has more than a thousand men. He’s understandably reluctant, but when Hancock presses him, Colvill agrees to attack. He orders his men to load and cap their pieces. He wants them to advance at double time, carrying their weapons so the bayonets point toward the throats of the enemy.

The Alabama regiments can’t believe it. They cannot believe that a force they outnumber four to one is coming at them. They are so stunned that they’re too slow in responding. They let the Minnesotans close to within 20 or 30 yards. The Minnesotans halt and fire one volley and, with their bayonets, charge into the Alabamians. There is a wild melee. It may last five minutes. The Minnesotans lose some 80 percent of their command, but they blunt the Confederate onslaught.

Meanwhile, Hancock gathers more regiments—Col. George A. Willard’s brigade, which today and the next will redeem its reputation and no longer be the Harpers Ferry cowards. He sends them forward to fill the gap in the Union front that has been opened east of the Trostle House by the collapse of Sickles’s Peach Orchard salient, and drives back Wilcox and Barksdale. Barksdale’s men have run out of gas; they finally give way under the force of this counterattack. As he leads his Mississippi brigade forward, Barksdale is riddled by bullets. He falls, and dies that night.

By 7 p.m. the Confederates continue to make headway. We’ve already spoken of the advance of Wilcox. Coming out of the woods and crossing the Emmitsburg Road in the vicinity of the white picket fence at the Rogers House site are the three small regiments of Col. David Lang’s Florida Brigade, the Second, Fifth, and Eighth. As they cross those post-and-rail fences, they advance and pivot toward Humphreys. They help capture one Yankee gun belonging to Lt. John Turnbull’s Companies F and K of the Third U.S. Artillery, and inflict more damage on Humphreys’s infantry.

Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock (center), commander of Federal II Corps, held key Union ground on July 1; by July 3 the “hero of Gettysburg” was in command of three-fifths of the Army of the Potomac.

Finally, Brig. Gen. Ambrose “Rans” Wright’s Georgians of Dick Anderson’s division, cross the open fields and fence lines separating Seminary Ridge and Emmitsburg Road before hitting the Union position at the Codori House and outbuildings. They close on Gulian Weir’s battery; three Union regiments break. It looks as if Wright is going to smash through the Federal position and win the day—except that as the Georgians look back, they see no one advancing on their left.

For a moment the Federal situation is desperate. Meade himself, along with his staff, scrounges up reinforcements in hopes of stopping Wright. Hancock rides over to Col. Francis Randall of the 13th Vermont and orders him to counterattack. Capt. John Lonergan’s Company A lets go an “Irish yell” and surges forward. Crossing the Emmitsburg Road, Lonergan’s people surround the Peter Rogers house and capture more than 80 Alabamans holed up on the property. Meade’s headquarters guard is the Tenth New York, the National Zouaves. He goes to them and the 71st Pennsylvania and tells them “I want you guys to drive back the foe.” Wright’s men close on “the angle”—where a stone wall changed direction, jutting west some 260 feet. They’re eyeball to eyeball with the 69th Pennsylvania. So far they’ve overrun three of the four guns of Lt. Gulian V. Weir’s Company C, Fifth U.S. Artillery, and two Napoleons of Lt. T. Fred Brown’s Company B, First Rhode Island Light Artillery.

Maybe it’s all over for the Union. But that is not to be. The Yankees stand tall. Wright’s men are driven back. The Yankees recover the two guns of Brown’s battery, they recover Weir’s cannon and the guns Lang’s Floridians had captured. The mighty Confederate counterattack has run its course. The Union again has rallied troops under the fearless General Hancock, who today demonstrates the value of personal leadership—something lacking in Lee, Hill, and Anderson. No wonder Wright will say the next day, when he learns of another attack coming across this same ground, “I was there yesterday. The trouble is to stay there after you get there.…”

As the Confederate attack on the Union left winds down, over on the Union right, on East Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill, the action begins to pick up. Richard Ewell had been under orders to provide a diversion during Longstreet’s attack. At first he did so simply by bombarding the Union lines opposite his corps. Now, with dusk approaching, he decides to turn his demonstration into an attack. Unknown to him, given the shift of Union forces to the left to stop Longstreet, he will face a weakened Union line, especially on Culp’s Hill.

Union soldiers of Brig. Gen. George Sears Greene’s New York Brigade of Brig. Gen. John W. Geary’s division of XII Corps, deployed along Culp’s Hill, throw up breastworks: The ground is too hard to dig into, so there are few entrenchments. That work continues through the day on July 2 before word comes that help is needed on the left flank to contain Longstreet’s attack. Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger’s division hustles over, leaving their former lines empty. As Longstreet’s onslaught gains more ground, orders come for Geary to rush support to cope with Longstreet’s increasing pressure, particularly with the loss of the Wheat Field. He marches off with two of his three brigades, leaving Greene to defend this entire XII Corps sector with his lone brigade of 1,400 men.

Greene’s a crusty veteran. Born in 1801, graduated second in his class from West Point in 1823, he’s an engineer who has no patience with the shoulder-to-shoulder tactics practiced by many officers who think they’re Napoleon. He has his men throw up the best breastworks possible, despite the patronizing remarks of General Geary, to make up for his shortage of manpower. On his extreme right—the right flank of the entire Army of the Potomac—is Col. David Ireland’s 137th New York, 423 men strong. Ireland’s defending a front that is about three times as long as that held by Chamberlain’s 20th Maine, although the two regiments are about equal in strength. He is going to be assailed by one of the largest brigades in this fight, Brig. Gen. George H. “Maryland” Steuart’s unit, consisting of five regiments and a battalion. To help defend his position, where there’s a depression between the two heights—the lesser and the greater—of Culp’s Hill, Ireland has his men throw up a traverse, a breastworks that extends back from the main line, so that if the enemy breaks the line the defenders can pull back behind the traverse and grimly hold on.

“Old Allegheny” Johnson attacks with only three of his four brigades at dusk on July 2. Another brigade, the Stonewall Brigade, has to be detached to do what cavalry should be doing, watching the Confederate extreme left on Hanover Road. The Confederates sweep up Culp’s Hill from Rock Creek, overrunning the vacated breastworks to Greene’s right, and surge through the saddle. Ireland’s people pull back behind the traverse. They’re fortunate because two regiments from I Corps arrive at the same time as reinforcements—those redlegged devils of the 14th Brooklyn and the Sixth Wisconsin of the Iron Brigade. Other regiments shore up the Union position, and Greene holds fast.

As Johnson deploys his men to attack Culp’s Hill late on the afternoon of July 2, to his right more Confederates prepare to advance against the apex of the Union position on East Cemetery Hill. Cemetery Hill is held by battered units of XI Corps along with several artillery batteries.

The gatehouse to Evergreen Cemetery, established in 1854, fronts on the Baltimore Pike. There’s lots of artillery here on July 2. You figure that your infantry should have no trouble holding this ground. The Yankees send forward a skirmish line—the 41st New York and the 33rd Massachusetts, then set up a battle line behind a stone wall edging alongside Brickyard Lane, a road that runs along the lower slope. There’s a gap in the line, just where the Confederates intend to go. What do you do? You’ve got a weak point, and since you’re not worried about the area perpendicular to the Baltimore Pike and Brickyard Lane, you’ll pull the 17th Connecticut out of there and send them down to plug the gap behind the stone wall fronting Brickyard Lane. So, you’ve closed a gap between the 75th Ohio and the 153rd Pennsylvania, but opened one between the 25th and 107th Ohio. What happens? The Louisiana Tigers come through the spot vacated by the 17th Connecticut.

The Confederate forces assigned to storm East Cemetery Hill are under Jubal Early, who likes to fight and hates Yankees. But he assigns only two of his four brigades—Harry Hays’s Tigers and Col. Isaac E. Avery’s Tarheels—to the attack. On the other side of the hill Robert Rodes takes one look at his bruised division and wonders whether he can do very much against the Yankee cannon and infantry up on West Cemetery Hill.

Federal breastworks in the woods on Culp’s Hill. Fighting on the Federal right flank along East Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill closed the second day of battle at Gettysburg.

Early isn’t worried, and when his men pour through that gap, the Union line gives way and the Rebels charge up the slope, overrunning one four-gun battery—Capt. Michael Wiedrich’s Company I, First New York Light Artillery—and capturing two of the six cannon of Capt. Bruce Rickett’s battery of Pennsylvania Light Artillery. It’s a pitched battle, lots of hand-to-hand combat, but it’s getting dark and the Confederates have no reserves with which to exploit their successes. Union reinforcements—including a II Corps brigade led by Col. Samuel “Bricktop” Carroll—rush to stabilize the Yankee line. The Yankees recover this position, recapture the six guns, and another serious threat has been dealt with. The Confederates again are left to muse about what might have been.

The fighting along East Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill closes the second day of combat at Gettysburg. Although the Confederates scored impressive initial gains, in the end timely reinforcements, adroit use of interior lines, and inspired leadership save the Army of the Potomac. Lee and Meade contemplate their next moves. At first Lee plans for a renewal of his offensive against the Federal flanks, but the Union counterattack at Culp’s Hill disrupts that plan. Meanwhile, at a small farm-house that evening, Meade meets with his generals to discuss what to do next.

Meade has his headquarters at the Widow Liester’s house from the morning of July 2 until the afternoon of the third. He has communication with Washington by courier. All of Meade’s corps commanders, his two wing commanders, and a few other generals crowd into the cramped parlor, a dozen men in a room that measures 14 by 16 feet. The wisest man of all is Gouverneur Warren, who, nursing a neck wound, sits on the floor and nods off in the corner.

Meade asks his generals what they make of the situation, what they recommend to do next, and whether they should take the offensive. He’s already told Washington that he intends to fight it out, but he wants to see what the others think. Basically, they agree with Meade’s decision to fight it out. As the meeting breaks up, Meade turns to John Gibbon, in command of II Corps, and tells him that if Lee attacks on the third, it will be against the Union center along Cemetery Ridge, a position held by Gibbon’s men. Odd thing about this conversation: There are no steps taken by Gibbon, Hancock, or Meade to strengthen the army’s center.

On the morning of July 3, Robert E. Lee decides that he will indeed assault the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. He orders Longstreet to organize the attacking force, composed of the fresh division of Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett and the divisions of J. Johnston Pettigrew and Maj. Gen. Isaac Trimble. Ewell is to again attack the wooded heights of Culp’s Hill. Lee hopes that Ewell’s assault might force Meade to weaken his center by withdrawing troops to reinforce Culp’s Hill. At the same time, Jeb Stuart, who had finally arrived on the field, will lead four brigades of cavalry in an attack beyond the Union right, with an eye toward getting in the Yankee rear, to spread panic and cut off the Army of the Potomac’s line of retreat—the Baltimore Pike. But by noon, the Federals have bested Ewell’s people in the fight for Culp’s Hill, and there will be no action until that afternoon to support Longstreet’s attack on Meade’s center.

Longstreet protests the attack against the Union center. He will say to Lee, “I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know, as well as anyone, what soldiers can do … [and] in my opinion no fifteen thousand men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.” Whether he said it at that time or not, there are not 15,000 men to form up for the attack. Because of the heavy casualties suffered on July 1, there are about 12,600 men available. Lee will be shocked when he sees how many North Carolinians, Alabamians, Tennesseeans, Virginians, and Mississippians are going forward with wounds that would normally incapacitate them for the day’s battle.

Although Longstreet places artillerist Colonel Alexander in charge of his corps artillery, Alexander does not have control over other Confederate Corps’s artillery. The attack suffers as a result, because each commander does his own thing. For example, Brig. Gen. William Nelson Pendleton, Lee’s chief of artillery, gives Alexander seven guns, all 12-pounder howitzers, double-charged with canister. When the advance begins these howitzers are supposed to go forward with the infantry, and when they close on the Emmitsburg Road, within 300 yards of the enemy, they will unlimber and open fire at point-blank range with canister. But nothing happens. The guns do not move forward.

At 1:10 p.m. Rebel cannoneers manning guns of Capt. Merritt B. “Buck” Miller’s Third Company, Washington Artillery, open fire; these two rounds signal the beginning of what would be the war’s best known cannonade, the distant roar of which was audible in Pittsburgh. Positioned along Longstreet’s front extending from the northeast edge of Spangler’s Woods to the Peach Orchard are 75 guns reporting to Colonel Alexander. To their left are 60 cannon manned by redlegs of A. P. Hill’s corps, and on the Southern left, in one massed battery positioned on Oak Hill, are 24 guns of Dick Ewell’s corps.

After two days of fierce combat, Confederate attacks had failed to dislodge Meade’s army. Determined to retain the initiative, Lee deployed his forces against the Federal center. The assault was to be made by the fresh division of Gen. George Pickett, supported by units of A. P. Hill’s battered corps led by Gens. J. Johnston Pettigrew and Isaac Trimble. Lee placed the attack under Longstreet’s direction. After a bombardment by massed Rebel artillery, Longstreet’s divisions started forward at 3 p.m. Overlapped by Federal fire from both flanks, the Confederates suffered fearful losses but were able to briefly break through the Federal line before being driven back by Federal reserves.

Initially many Confederate gunners use too much elevation and overshoot their primary targets: the Union infantry and artillery reporting to General Hancock posted behind the stone walls along Cemetery Ridge, extending from Ziegler’s Grove on the north to beyond The Angle to the south. Defective fuses also plague the Rebels when they employ explosive shells and spherical case shot, or shrapnel.

Fifteen to 20 minutes elapse before 118 Union cannon emplaced along a two-mile front extending south from Cemetery Hill to Little Round Top return the enemy’s fire. The rate of counter battery fire by Yankee redlegs is dictated by two forceful personalities, General Hancock and Chief of Artillery Brig. Gen. Henry W. Hunt. Hancock, an infantryman, calls for the Union artillerists along the II Corps front to fire as rapidly as possible. He correctly believes that this encourages his foot soldiers. Hunt, one of the Civil War’s premier artillerists, calls for his gunners to limit their counter battery fire to one projectile per gun at two-minute intervals. He wants his people to conserve their canister, explosive shell, and spherical case shot to break the back of the Confederate infantry when and if they reach the Emmitsburg Road.

The three Confederate divisions wait and wait. J. Johnston Pettigrew has succeeded the wounded Harry Heth as commander of Heth’s division. Arriving on the field in late morning is Isaac Trimble, 61 years old, a West Point graduate, an engineer, and a Yankee hater. He takes charge of Pender’s men, Pender having been wounded on July 2. And then there’s George Pickett. Wounded at Gaines’s Mill, he did not return to duty until the Battle of Fredericksburg, where he saw little action. He was not at Chancellorsville. He’s eager to fight. He’s in charge of three brigades, commanded by Brig. Gens. Richard Garnett, James Kemper, and Lewis Armistead. Garnett had a run-in with Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson at the Battle of Kernstown in March 1862; eventually he transferred to Longstreet’s command. Garnett’s hurt: He will ride forward with his men, presenting an easy target. Kemper’s a non-West Pointer, a veteran of the Mexican War. Then there’s Lewis “Lo” Armistead, a prewar comrade of Hancock.

Longstreet has an out. If the bombardment does not suppress the Union guns, the assault can be called off. Longstreet delegates that decision to Alexander. At first, after the Union cannon open fire, they give as good as they receive. Alexander sends a message to Pickett and Longstreet that it looks like he is not going to be able to overwhelm the Union artillery. Then there’s a lull in the action. Alexander sees what appears to be Union guns being bested; other guns are limbering up and withdrawing. It looks as if the bombardment may have worked. Alexander sends a message to Pickett, “For God’s sake come quick. The 18 guns have gone. Come quick or my ammunition will not let me support you properly.”

It is about 3 p.m. when Longstreet reads the message. Pickett, who commands the guide division, says, “Should I advance my division?” Longstreet can’t bring himself to say “yes.” But he bows his head, which Pickett assumes means “yes.” Pickett rides back to his men, faces them, and commands: “Men of Old Virginia, prepare to charge the enemy! Forward! Guide center! Quick time! March!” And so the line steps out, and as it does the other divisions see what’s happening and they move forward as well. There are many swales and depressions in the fields where they advance, offering good cover; at times they can’t even see Cemetery Ridge. But the silence of the Union artillery is short-lived, because Hunt was simply rotating batteries in and out of line; from Little Round Top Union artillery hits the advancing lines from the flank.

A West Point classmate of McClellan and Jackson, Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett led the famous last-ditch charge against the Federal center on the third day of battle at Gettysburg.

As Pickett’s men approach the Emmitsburg Road they converge on Pettigrew’s right. At the same time, however, Col. J. M. Brockenbrough’s understrength Virginia Brigade on Pettigrew’s left begins to give way, as the Eighth Ohio fronts south and fires into its flank. Kemper’s men push toward Cemetery Ridge, and Brig. Gen. George Stannard’s Vermont brigade moves out toward the Emmitsburg Road, wheels right, and fires into the flank of the advancing Rebels. Kemper is hit; his brigade gives way and crowds to the left, increasing the confusion in Pickett’s ranks.

Confederate dead gathered for burial near the Emmitsburg Road south of Gettysburg. The costly three-day campaign left more than 51,000 American men dead, wounded, or missing.

Pickett’s men find when they come to the Emmitsburg Road that much of the sturdy post-and-rail fencing is standing, and climbing over it or through it or tearing it down takes time, leaving them terribly vulnerable to enemy fire. Union soldiers, taking deadly aim, chant “Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg!” Still the Rebels swarm forward toward the angle in the stone wall near a copse of trees in the center of the Union line. Garnett is hit; unhorsed, he falls, and his body is never recovered. (After a score of years his watch and sword show up in a Baltimore pawn shop.)