MAY 18, 1863–JULY 4, 1863

Vicksburg, Mississippi, sits high atop a series of steep hills and bluffs on the east bank of the Mississippi River about 40 miles west of the state capital at Jackson. The city and its surroundings formed a natural citadel for the Confederacy, enabling Rebel forces there to contest Union control of the Mississippi River while maintaining communications with the trans-Mississippi Confederacy. A thriving prewar steamboat port, Vicksburg was linked by the Southern Railroad of Mississippi to nearby Jackson and rail connections to upper Mississippi, New Orleans, and the Deep South. With Federal Flag Officer David G. Farragut’s capture of New Orleans in April 1862 and the advance of Federal amphibious forces from Cairo, Illinois, as far south as Memphis, Tennessee, Vicksburg remained as the South’s key bastion blocking Federal plans to sever the Confederacy by gaining control of the entire Mississippi River. The city was so vital to the Confederacy that President Jefferson Davis referred to it as “the nailhead that held the South’s two halves together.”

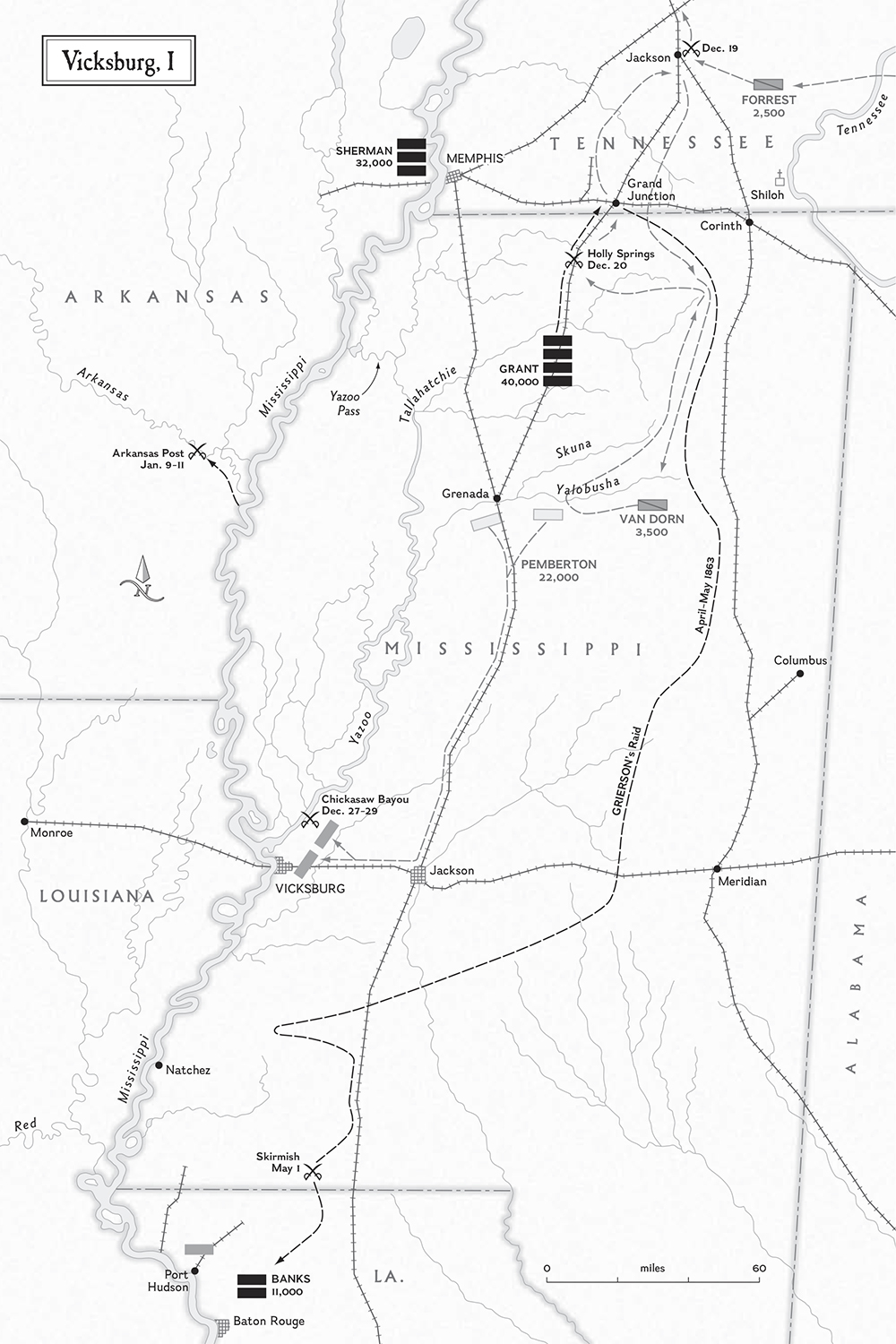

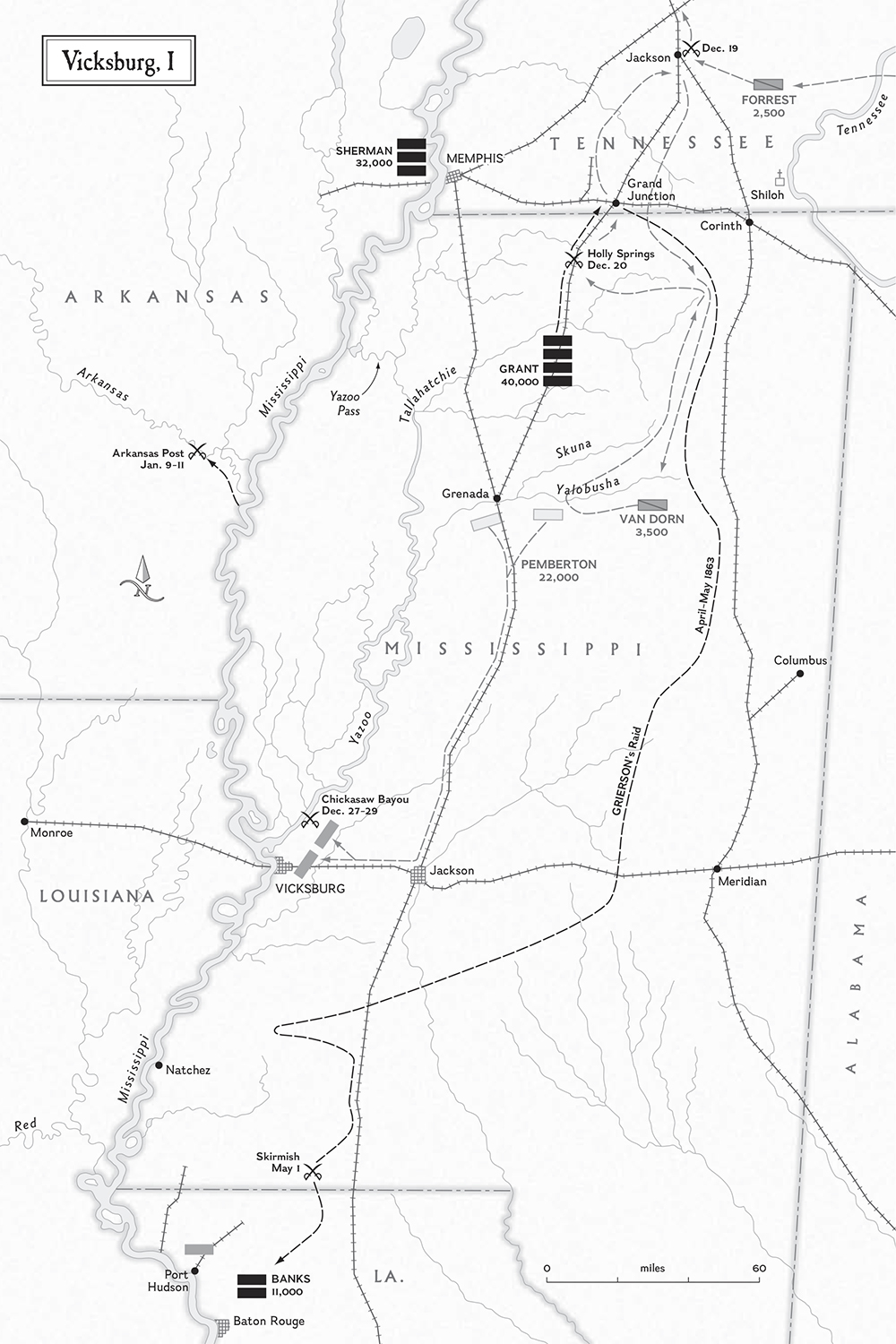

Vicksburg had attracted the attention of Union military planners since the spring of 1862. Several early efforts to capture the river citadel had met with failure. An attempt by Farragut’s deepwater warships and supporting ironclad gunboats of the “brown water” navy in June and early July 1862 to dash up- and downriver and seize Vicksburg failed to subdue the city. In December 1862, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant launched a two-pronged advance against Vicksburg—40,000 Federal troops under Grant advancing south through Mississippi along the Mississippi Central Railroad and a movement by water of 32,000 men under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman against Walnut Hills on the Yazoo River to the north of Vicksburg. The campaign ended in a humiliating defeat.

Undaunted, Grant reunited most of his Army of the Tennessee at the west side of the river north of Vicksburg at Milliken’s Bend and Young’s Point and pondered how best to approach and capture Vicksburg, garrisoned by a large Confederate force under Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton. From the beginning Grant realized that once spring came, he must move along the bayous, find dry ground, and cross the river somewhere to bypass the city’s formidable river batteries and attack Vicksburg from the south.

Rejecting the advice of his trusted lieutenant William T. Sherman, Grant refused to take his army back to Memphis to try another overland advance southward. His reasons were not purely military; he realized that his senior corps commander, Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand, was doing all he could to supplant his superior as commander of the Army of the Tennessee. A retrograde movement northward would be interpreted as a retreat, and calls for Grant’s displacement, already audible, would increase in volume and number.

Thus, as he awaited the advent of spring, Grant set his men to work on a series of projects, each looking to open another route to Vicksburg. Later he would claim that he did so merely to keep his men busy and healthy; in truth, however, he would take whatever opportunity came his way.

When Grant arrives at Young’s Point, Louisiana, on the 30th of January, he takes active command of the campaign to capture Vicksburg and reorganizes the army into four corps, three in Louisiana and one, the XVI, under Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut, back in Memphis. Figuring he has to humor the President, whose early experiences as a Mississippi flat-boat man make him partial to the idea of digging canals, Grant breaks out the shovels and tells his men to get to work. They are going to furnish large working parties to work on this canal, soon to become known as “Grant’s Canal.” The canal had been started by Brig. Gen. Thomas Williams during Farragut’s June-July expedition in an attempt to cut through the mile-and-a-half-wide hairpin bend peninsula at Vicksburg. This would allow Federal forces to bypass the city out of range of its formidable batteries.

Sick lists grow. Death lists lengthen. After they get the canal cut through to a certain depth, they bring down four big floating steam dredges. They have steam pumps going to control the depth of water in the ditch. But on March 7, 1863, a massive crevasse opens in the Young’s Point area and the Yankees find themselves perched on the levees like chickens in a flood, and the ground around is inundated. The high water soon begins falling, but by this time what are the Confederates doing? They quickly move their big guns downstream well below the South Fort area of Vicksburg’s defenses onto high ground opposite the mouth of the canal. Even if you do run boats through the canal you are going to be sailing a mile and a half on a straight course with Confederate cannon commanding the canal’s exit. That isn’t going to be healthy.

In February a Federal force of 10,000 blasted their way through the levee at Yazoo Pass, 325 river miles north of Vicksburg, in an attempt to approach Vicksburg via the Tallahatchie and Yazoo Rivers, a route of nearly 700 miles. After fighting their way through high water past Confederate obstructions the Federals found their way blocked in mid-March by a force under Maj. Gen. William W. Loring, who had established Fort Pemberton 90 miles as the crow flies north of Vicksburg. An attempt in March to move an expedition 200 miles up Steele’s Bayou to the rear of Fort Pemberton also failed.

Grant reevaluates his situation and decides to abandon the canal, along with his other interior waterway endeavors; he’ll move his army down the west side of the Mississippi and find another place to cross.

The Mississippi is an alluvial river, and through the eons of time its course has shifted west of the bluffs to the west beyond Monroe, Louisiana. In its meandering path and along its different courses, it has built up natural levees. Many old channels remain as oxbow lakes separated from the main channel. The land along these natural levees is higher than in the nearby swamps, fertile, and heavily cultivated by wealthy planters. The width of these natural levees seldom exceeds two miles.

After several unsuccessful attempts to capture Vicksburg in the fall of 1862, Grant planned to shift his army to the east bank of the Mississippi to capture the city from the south. Vicksburg was guarded by two Confederate forces, one under Maj. Gen. Carter L. Stevenson in Vicksburg and a second around Jackson under General Pemberton. On the night of April 16, Rear Adm. Porter took his Federal fleet south past the Vicksburg batteries and ferried two Federal corps across the river on April 30. Between May 1 and 12, the Federals defeated Rebel forces at Port Gibson and Raymond and, on May 14, won a decisive engagement at Jackson, isolating Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who had recently arrived from Tennessee. Grant defeated Pemberton at Champion Hill on May 16, forcing the Confederates to withdraw into the defenses of Vicksburg.

On the last day of March, a Union column leaves Milliken’s Bend to reconnoiter and open a road to New Carthage, 40 miles to the south by twisting waterways and 20 miles below Vicksburg in a straight line. But when they get to New Carthage the man-made levee fronting the river has crevassed. This slows the southward march as engineers search for and open a road along the Bayou Vidal natural levee.

To facilitate the movement of the tons of supplies needed to support the army, the Federals begin another canal linking Duckport Landing on the Mississippi with Walnut Bayou. The steam dredges are redeployed to the new project, but a rapid fall in the stage of the Mississippi dooms this undertaking.

By mid-April the Union buildup in the New Carthage area has reached the point where Grant calls on the navy. Rear Adm. David D. Porter is ready and eager to provide the muscle to get the army across the mighty river. The night of April 16 sees Porter successfully challenge the Vicksburg River batteries with eight gunboats and three steamboats. Although they take a hammering, only one vessel is lost. Six nights later, six more unarmed boats ran the gauntlet, with the loss of one. They bring with them a number of barges lashed to their sides.

Meanwhile, Grant’s plan to stage his army at New Carthage has been scrubbed. He now proposes to embark his troops at Hard Times Landing on the lowland side and establish his Mississippi beachhead at Grand Gulf. Let us look at the Grand Gulf defenses. Since mid-March, the Confederates have rushed Brig. Gen. John Bowen’s two-brigade division to Grand Gulf. They man two forts, Wade and Cobun—you don’t want forts named after you, because it usually means you are dead.

By April 28, Grant’s troops and Porter’s fleet are ready to undertake what, for that time and place, is a formidable amphibious operation. That evening over at Hard Times Landing, four miles upstream, 10,000 men of John A. McClernand’s corps board transports and barges. The unit you don’t want to be with is the 67th Indiana. Lt. Col. Theodore Buehler and his men are in leaky barges, and they spend the night bailing to keep afloat. Porter and his seven ironclad gunboats have the mission of suppressing the fire of the Confederate forts. Porter has reconnoitered them from upstream. He knows where they are located. Grant, early on the morning of the 29th, boards the tug Ivy and takes station upstream well out of range of the forts’ cannon. Behind him are 10,000 men waiting aboard vessels. At 7 a.m. on the 29th, signal flags go up: The gunboats cast off. They divide into two divisions, one consisting of four “city series” gunboats—the Pittsburg, Louisville, Mound City, and Carondelet. The other division includes the Benton, 16 guns, flying Porter’s pennant. Benton is accompanied by the Lafayette, a new ironclad, and the Tuscumbia. The latter is a type of vessel that the Truman Committee would have investigated in World War II. It was a rip-off by the contractor. When he secured the armor plating to the timber backing, he fastened the spikes without having them secured by a nut to the opposite side. It isn’t a shipshape vessel. This trio is to take out the upper battery, Fort Cobun. At 8 a.m. the ironclads come down the river in column. As they round Coffee Point, they open fire; first with their bow guns, then their port broadsides as they pass Cobun.

The Pittsburg, Mound City, Louisville, and Carondelet take position within a quarter mile of Fort Wade with their bows pointed upstream and their starboard 32-pounder guns bearing on the Rebels. Although each “city series” ironclad has 13 guns—they have three firing forward, four to port, four starboard, and two astern—meaning that the Yankees don’t have four times 13 guns firing on Fort Wade. Only 16 guns at one time can bear on the fort. The other three ironclads engage Fort Cobun.

The Confederates reply with the four big guns emplaced in each fort. Col. William F. Wade of St. Louis is in charge of the lower battery. He probably should not have been walking back and forth, exposing himself, because a charge of canister will come toward him and he’s going to lose his head, literally and figuratively.

By 10 a.m. the guns of Fort Wade are silent. One of the 32-pounders has burst. Mounds of earth have been torn up. But Porter’s division doesn’t silence Fort Cobun; the Tuscumbia, no match for the Rebs, is taken out of the fight. The other two ironclads, reinforced by the four “city series” gunboats, compel Fort Cobun to slow its rate of fire. About 1 p.m. Porter takes a break and confers with Grant. Between them, since Porter can’t guarantee suppression of the Confederate fire, the decision is made to return the invasion armada to Hard Times Landing and march the troops across the base of Coffee Point. Somewhere south of there they’ll cross the river.

Grant’s soldiers march across Coffee Point during the late afternoon and night of the 29th. After dusk, the gunboats run downriver along with the transports and barges, successfully challenging the Grand Gulf gauntlet. On the morning of the last day of April, the navy begins embarking the Union forces at Disharoon’s plantation to shuttle them across the Mississippi River downstream to Bruinsburg Landing, where Bayou Pierre flows into the Mississippi.

A Grant staffer, Lt. Col. James H. Wilson, had been in this area scouting out the ground. Grant romanticizes in his Memoirs that he learned about where to cross the Mississippi from a black informant. I’m sure he ran into the black refugee. I’m certain the refugee told him about the good road leading east from Bruinsburg toward Port Gibson, but I’m equally certain that Grant had other solid information besides what that fellow told him. When he starts south from Hard Times, he considers crossing at Rodney. If he goes to Rodney, he’s going farther south, which would give the Confederates more time to concentrate to oppose his landing.

When General Pemberton learns from General Bowen, charged with the defense of Grand Gulf, that Grant is concentrating his army at Hard Times preparatory to crossing the Mississippi, he directs General Stevenson at Vicksburg to send 5,000 men to Grand Gulf, if practicable. But Stevenson is distracted by General Sherman’s expedition up the Yazoo River, and he procrastinates for vital hours. Brig. Gen. Edward Tracy’s Alabamians will not leave Vicksburg for Port Gibson until 7 p.m. on the 29th. Brig. Gen. William E. Baldwin will follow two hours later.

Grant crosses the Mississippi with McClernand’s corps, some 16,000 strong, and two of Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s three XVII Corps divisions, about 11,000 soldiers. Bowen has perhaps 4,200 defenders. Although Tracy and Baldwin are ordered to bring 5,000 men, they are going to have heavy straggling as they go south. Bowen will have 8,000 men and 12 cannon to battle 24,000 Yankees supported by 60 guns.

Having reached dry land on the east bank of the Mississippi, Grant’s forces move inland. On May 1 they encounter John Bowen’s Confederates south of Grand Gulf, four miles west of Port Gibson on the farm owned by A. K. Shaifer.

What can Bowen do? If he takes everyone down to Port Gibson, he leaves Grand Gulf in his rear open to attack by Porter’s fleet. He holds half his men at Grand Gulf and sends Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green with his Arkansans and Missourians to Port Gibson. When Green gets there he goes west out of Port Gibson, two miles to the junction of the Rodney and Bruinsburg roads. He doesn’t know whether the Yankees are coming from Bruinsburg or Rodney, so, upon arrival of Tracy’s Alabamians, he splits his force. Green heads out the Rodney Road and posts his brigade near Magnolia Church, half a mile east of the A. K. Shaifer House; Tracy goes out the Bruinsburg Road and positions his men to cover a plantation road that links the Rodney and Bruinsburg roads. Tracy anchors his left at Point Lookout, commanding Bayou Pierre.

No one can improve on General Grant’s description of the local landscape. He wrote in his Memoirs, “the country in this part of Mississippi stands on edge, the roads running along the ridges except where they occasionally pass from one ridge to another. Where there are no clearings the sides of the hills are covered with a very heavy growth of timber and with undergrowth, and the ravines are filled with vines and canebrake almost impenetrable.”

Grant wants to get as far inland as he can before he fights a battle. He hopes to be on the high ground. He doesn’t want to be like Billy Sherman in late December 1862, when he was down in the low ground fronting Chickasaw Bayou with the Confederates on the slopes of Walnut Hills and the high ground beyond. Brig. Gen. Eugene Asa Carr’s division of the XIII Corps takes the lead as the army marches inland from Bruinsburg.

A West Pointer and former cavalryman, Carr assigns the lead to Col. William M. Stone’s brigade. A future governor of Iowa, Stone employs the 21st Iowa and one cannon as his vanguard. A night march is called for, and the Rodney Road as it wends its way along the ridges and drops down to cross streams is as picturesque today as it was challenging to Grant’s soldiers. The Hawkeyes find the Spanish moss that drapes from the trees romantic, but not the snakes and alligators.

Shortly after midnight on May 1 at the A. K. Shaifer House, the Iowans clash with a Confederate outpost and the first shots in the Battle of Port Gibson are fired. This initiates a nighttime firefight between Green’s Arkansans and Missourians posted out by Magnolia Church and Carr’s people. By 3 a.m. the fighting ceases as the blue and gray anxiously await the dawn to sort out where they are in a mazelike landscape.

Daylight reveals to the Federals that, in addition to Green’s people to their front astride Rodney Road, Tracy’s Alabamians are posted on a ridge to their rear. Along this ridge runs a plantation road linking the Rodney and Bruinsburg roads. How will Generals Grant and McClernand confront this situation? This is the only Civil War battle with which I am familiar where soldiers will advance in the opposite direction to get at the foe.

By 8 a.m. two more XIII Corps divisions have reached the Shaifer House staging area via Rodney Road. While Brig. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus’s division advances northwest up the plantation road, Carr’s people, reinforced by newcomers of Brig. Gen. Alvin P. Hovey’s 12th Division, thrust southeast down Rodney Road, intent on smashing Green’s Magnolia Church roadblock. Although Osterhaus’s division outnumbers Tracy’s Alabamians more than two to one, its progress is slow. Among the Confederates killed is General Tracy; his men, now led by Col. Isham Garrott, stand tall, and Osterhaus calls for help.

Meanwhile, Carr and Hovey by 10 a.m. overwhelm Green’s Magnolia Church roadblock, and send the Rebels skedaddling. The arrival of Confederate reinforcements—Baldwin’s brigade from Vicksburg and Col. Frank Cockrell’s Missourians from Grand Gulf—enables General Bowen to cobble together a force in the deep hollow where the confluence of the White and Irwin branches forms Willow Creek. Here the Rebels checkmate McClernand’s corps.

By mid-afternoon the last of McClernand’s four divisions—A. J. Smith’s—and Maj. Gen. John A. “Black Jack” Logan’s division of McPherson’s corps reach the field. To break what is becoming an embarrassing impasse, Logan sends Brig. Gen. John E. Smith’s brigade to assist Peter Osterhaus. The Yanks file off into the canebrakes and rugged ground separating Bruinsburg Road and Bayou Pierre. They soon turn the Alabamians’ right flank, whose left had been earlier reinforced by Green. If they continue to fight, these Johnny Rebs will be cut off from Grand Gulf. Retreat is the order.

At the outset of the war, Illinois Congressman John A. McClernand resigned his seat, raised a brigade of Illinois volunteers, and was made a brigadier general.

The Confederates disengage, and Garrott and Green head for Grand Gulf. Bowen’s Confederates, who have checked the Yankees over on Rodney Road, are now in deep trouble. If they stay there, the bluecoats will sweep east along the Bruinsburg Road, capture Port Gibson, and these butternuts will get a free trip north to Union prison camps. So, what do they do? Col. Francis M. Cockrell takes his Missourians and heads for Grand Gulf; William Baldwin and his men retreat to and through Port Gibson.

By 6 p.m. Grant has won the Battle of Port Gibson. The fight has lasted from 1 a.m. until 6 p.m. The Confederates have fought a magnificent 17-hour delaying action by employing terrain skillfully to slow the Union forces. Hopefully, reinforcements are going to join them. They are on the way, but none of them will show up until the morning of May 3. By the third, it is too late. Grant has secured his bridgehead east of the Mississippi, and he isn’t going to be driven back into the river. Through deception and diversion Grant has overcome the Confederate advantages of terrain and now holds the initiative. Grant orders McClernand to pursue the Confederates. The human toll as reported lists 60 Confederate dead, 340 wounded, and 387 missing, most of the latter captured. Union losses number 131 dead, 719 wounded, and 25 missing.

According to orders he receives from Washington, Grant is to entrench at Port Gibson and send a corps or go himself with a corps and join Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. “Nothing Positive” Banks in the capture of Port Hudson. Grant knows that it takes at least two weeks to send and receive messages to and from Washington. He has also received word that Banks has taken a roundabout route by way of Bayou Teche to Alexandria and will not begin an attack on Port Hudson until at least May 10. Having finally secured a lodgment on the high ground, east of the Mississippi, he will not send a corps to cooperate with Banks. Instead he will pause, regroup, call down Sherman from Milliken’s Bend and Young’s Point, and then forge ahead.

Port Gibson and the occupation of Grand Gulf are significant achievements for Grant, although he would have wanted even more. Even as he grumbles about the performance of General McClernand, who chose a critical moment during the engagement at Port Gibson to deliver a stump speech to his men, Grant has more important decisions to make.

He decides to mass his three corps east of the Mississippi and move into the interior of the state, with the Big Black River on his left flank as he probes the Confederate positions between Vicksburg and Jackson. Grant hopes that by interposing his army between the Confederate forces at Vicksburg and Jackson, he can defeat each before they can combine against him. Aware that by advancing in that fashion he risks having Pemberton dash south to cut his supply line, Grant determines that his men will live partially off the land, with wagon convoys carrying medicine, certain rations, and ammunition. These trains will be escorted by parties of reinforcements departing almost daily from Grand Gulf for the front.

When Sherman arrives at Grand Gulf, Grant orders the army to move out. He now has his army of maneuver: McClernand and his four divisions, Sherman with two divisions, and McPherson with two divisions. With the coming of Sherman, Grant is at a point in his career where he has to make a key decision. General Loring is in field command of the Confederate troops then entrenching along a line extending from near Warrenton on the Mississippi seven miles below Vicksburg east to the Big Black River. The Confederates are dug in on bluffs looking south; they expect an attack against Vicksburg, coming north from Grant’s Hankinson Ferry bridgehead on the Big Black.

Grant, however, decides on a daring move: a hook to the northeast, where he can threaten the state capital at Jackson and defeat and disperse the Confederate forces assembling there. Orders go out on May 7 and the Federals begin to move. At Reganton, on the ninth, Grant turns McPherson’s XVII Corps into the Utica Road. McClernand, trailed by Sherman, follows the Natchez Trace from Rocky Springs to Cayuga and beyond. McClernand’s people on the 11th halt to let Sherman pass as Grant now splits his army. As he closes northward on the vital railroad linking Vicksburg and Jackson, he will have McClernand on the left, Sherman in the center, and McPherson on the right. With Grant’s army moving farther and farther northeast, the Confederates abandon the earthworks they are throwing up south of Vicksburg and change direction 90 degrees to front east.

The Confederates also rush troops toward Jackson. Pemberton, still uncertain as to what Grant plans, masses 20,000 men at Edward’s Station about ten miles east of Vicksburg. Others come from as far off as Charleston, Savannah, Port Hudson, and Tullahoma but must pass through Jackson. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston boards a train on May 10 at Tullahoma, Tennessee, and hurries westward to take charge of these Jackson-bound brigades.

By May 11 McPherson’s XVII Corps is preparing to march on Raymond, a small Mississippi town about 15 miles west of Jackson. Once one of Grant’s staff officers, James Birdseye McPherson is a favorite with both Grant and Sherman; however, he has little experience as a combat commander. Among the Confederate brigades marching to the aid of Vicksburg is a force of 3,000 men under Brig. Gen. John Gregg. They had been ordered up from Port Hudson to Jackson and had been sent west toward Raymond to prepare for a possible strike at Grant’s rear if the Federal commander made a move toward Vicksburg across the Big Black River. Gregg has been warned by Pemberton that there may be a Yankee feint toward Raymond, but he is not expecting the advance of a major enemy force.

Learning that there is a Union brigade at Utica, near Raymond, Pemberton orders Gregg to intercept it. Gregg arrives at Raymond on the afternoon of May 11. The “brigade” of Union infantry is actually six brigades of infantry and 22 cannon—12,000 men of McPherson’s XVII Corps. Gregg understands that when he arrives he’ll meet with Col. Wirt Adams’s cavalry, who are to reconnoiter for him. So, when Gregg arrives, he is nonplussed to find no Adams, only some 40 horsemen commanded by Capt. J. M. Hall. Gregg sends Hall down the Utica Road to find out who’s there.

Hall soon sends back word that Yankees are coming. Gregg, going on the assumption that the average Union brigade numbers 1,500 men, believes that with his command, 3,000 strong, he has no cause for worry. These men are Texans and Tennesseeans. They know what it is like being in Yankee prison camps—many had been captured at Fort Donelson back in February 1862. They will fight like hell. Gregg will act aggressively throughout most of the day. He’s going to carry the fight to McPherson, who today will be far too cautious or, perhaps worse, timid.

What does Gregg do? He says to Col. Hiram Bronson Granbury, “Take your Seventh Texas and the First Tennessee Battalion and go out to the high ground commanding the junction of the Port Gibson and Utica roads, and put three guns into position.” He tells Col. Calvin H. Walker, “Take your Third Tennessee and form them on the reverse side of that high ground rising northeast of the Fourteenmile Creek Bridge.” To Lt. Col. Thomas W. Beaumont he says, “You go down the Gallatin Road, with your 50th Tennessee, supported by Col. Randal W. MacGavock of the 10th and 30th Tennessee.” Gregg’s plan is to engage the Yankees to his front and then order Beaumont and MacGavock to come down and turn the Union right flank. Good idea, if there are only 1,500 Yankees. Bad idea if there are 12,000 Yankees.

About 10 a.m. the Federals arrive on this high ground, known today as McPherson Ridge. McPherson is up here along with “Black Jack” Logan. They look out across the Fourteenmile Creek bottom. The Confederates see Yankees up here, and there come three puffs of smoke as Capt. H. M. Bledsoe’s Missouri Battery opens fire. The lead Union battery is up front already. Captain Samuel S. DeGolyer of the Eighth Michigan Light Artillery unlimbers his six guns and duels with the Rebs.

Up comes another Union battery, Capt. W. S. Williams’s Third Ohio Battery. Now there are 12 Union guns in action. Brig. Gen. Elias S. Dennis deploys his infantry brigade guiding on Utica Road, the 30th and 78th Ohio to the left, the 20th Ohio and 120th Illinois to the right. It is open ground until they close on Fourteenmile Creek, then they encounter woods. The Yankees move out. It is very dusty. The Yankee guns blast away. It looks good to Gregg. A Union brigade—that’s just what he thought. There might, however, be a few more cannon than appropriate for a brigade. Gregg puts his plan into action. At noon, he orders Granbury to advance. The Texans surge into the woods east of the bridge and engage the Federals. The Yankees stop dead in their tracks. Meanwhile, Walker deploys his men in the lee of that ridge. McPherson looks to Logan. Black Jack calls up John E. Smith’s brigade—four Illinois regiments and the 23rd Indiana. They come down off McPherson’s Ridge and advance across open fields with the 23rd Indiana in front.

The Hoosiers cross Fourteenmile Creek, breaking formation to climb down and up the steep banks. They emerge, start dressing their ranks, and as they are doing so, the Third Tennessee comes over the ridge and smashes into them. The Indiana boys flee across the creek, the Tennesseeans in hot pursuit. As the Confederates come out of the woods and enter a field, two Yankee regiments—the 30th Illinois and 45th Illinois—are concealed in nearby trees. They open fire. The Confederates scatter and retreat into the timber. Up to this time the Seventh Texas and Third Tennessee have engaged nine Union regiments and fought them to a standstill.

Colonel Beaumont has gone out Gallatin Road to secure the high ground beyond Fourteenmile Creek where it is crossed by the road. If Gregg’s estimate of the situation is correct, Beaumont once on the ridge will be beyond and well east of the Utica Road and positioned to envelop McPherson’s Ridge and capture the guns of the three Union batteries now unlimbered there. But when Beaumont gains this vantage point, he sees through clouds of dust long columns of Union infantry marching up the Utica Road. Beaumont calls off his attack and sends a messenger to tell Gregg what is happening. The courier does not get through. Beaumont recalls his regiment and Colonel MacGavock occupies the commanding ground (known today as MacGavock’s Hill) with his consolidated 10th and 30th Tennessee. The former is an Irish regiment. Nearby on MacGavock’s left is the 41st Tennessee.

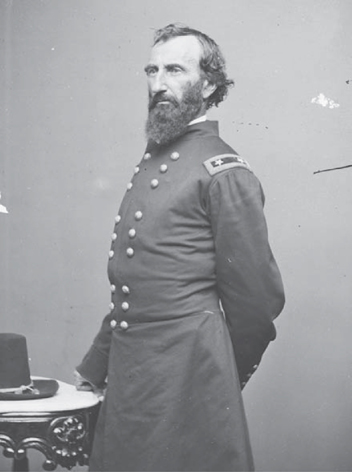

Chief engineer to Grant during the Union advance through Tennessee, Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson commanded the Federal XVII Corps during the Vicksburg campaign.

By this time Logan has called up and committed Brig. Gen. John D. Stevenson’s brigade. Two of Brig. Gen. Marcellus M. Crocker’s three brigades are also on the field. More than 10,000 bluecoats demonstrate to the butternuts that their fire-eating politicians were in error when, as the secession crisis threatened breakup of the Union, they boasted that one Southerner could whip ten Yankees. Numbers now tell. McPherson, by 3 p.m., gets his act together after five hours. Soon Colonel MacGavock is dead, and the Rebels give ground, slowly at first and then rapidly. By four o’clock they retreat through Raymond, taking the road toward Jackson by way of Mississippi Springs.

McPherson marches into Raymond. First in are from the 20th Ohio of Dennis’s brigade. The good ladies of Raymond have arranged on the courthouse square a super picnic lunch. They plan to feed the Confederates when they return victorious. The Rebels, however, do not pause, let alone stop, in Raymond to partake of the picnic laid out for them. The Buckeyes and friends make sure it does not go to waste. Union battle casualties are 68 killed, 341 wounded, and 37 missing; Gregg listed his losses as 73 dead, 252 wounded, and 190 prisoners.

Among Grant’s senior officers, James McPherson combined intelligence, good looks, and loyalty. But of Grant’s three corps commanders present with the army at Raymond, as later in the campaign, he will prove to be overly cautious and least willing to close with the foe. This is true whether discussing the May 22 Vicksburg assault, the October 1863 Canton expedition, or Georgia’s Snake Creek Gap in May 1864.

News of McPherson’s victory at Raymond causes Grant to change his plans. Instead of moving northward, he’ll send Sherman and McPherson against Jackson, with orders to drive out the Confederates there, sever the area railroads, and destroy whatever manufacturing they encounter. McClernand will swing north and then east, keeping an eye on Pemberton at Edward’s Station; once McPherson and Sherman finish their mission, they are to join McClernand and attack Pemberton. In Jackson on May 13, an exhausted and ill Joseph Johnston arrives to take command in the aftermath of Confederate defeats at Port Gibson and Raymond. Because Federal forces threaten northern Mississippi and Alabama, the ailing Johnston has had to take a 300-mile detour to travel from Tennessee to the front in Mississippi. With reinforcements he will have perhaps 12,000 men to face Grant’s 20,000.

On the 13th, Union columns move out in accordance with Grant’s new operational plan. Demonstrating flexibility—one of his strong points—Grant changes direction 90 degrees. He turns toward Jackson. On the morning of May 14, McClernand’s corps concentrates in and around Raymond to guard Grant’s rear. McPherson advances with two divisions down the Clinton-Jackson Road toward Jackson. Sherman bears in on the Raymond Road.

General Johnston arrives in Jackson at 6 p.m. on May 13. He takes a room in the Bowman House near the Mississippi capitol. He orders General Gregg, who is commanding in Jackson, to send everything of military value out of Jackson up the road to Canton, 30 miles northeast of Jackson. This will make it harder for Pemberton to combine his force with Johnston’s. He also sends a message to Richmond couched in the stink of defeatism, “I am too late.”

Brig. Gen. William H. T. “Shot Pouch” Walker, joined by Col. Peyton H. Colquitt, goes out and sets up a roadblock placing their two brigades on the Clinton road. Their people are far out in front of the Jackson earthworks, which Johnston says are improperly located.

Just as skirmishing starts at Colquitt’s roadblock between the Confederates and McPherson’s vanguard, clouds burst and rain pours down. So hard is the rain that men cannot open their cartridge boxes. Everything is suspended. This is positive for the Confederates, because they learn that Sherman is coming in on the Raymond Road. They rush Col. Albert Thompson and a small force of mounted infantry over there to stall Sherman.

It stops raining in the early afternoon, and the Yanks advance in overwhelming strength. The Confederates fight a delaying action to cover the movement of their trains north. By 5 p.m., the Rebels are out of Jackson and have retreated up the Canton Road. Grant establishes headquarters in the Bowman House, reputedly in the same room where Johnston had slept the previous night.

At the time the Federals capture Jackson, Pemberton’s army is concentrated in the Edward’s Station area. Johnston sends orders in triplicate to Pemberton telling him that four divisions of Federals are in Clinton, about ten miles west of Jackson. He has lost track of Sherman, who is at Mississippi Springs. With the enemy at Clinton and between them, Johnston directs Pemberton to march east, and he will close on Grant from the opposite direction with the Jackson Confederates. Pemberton gets his copy at Bovina on the morning of May 14. Some 12 hours before, an intelligence coup betrays into Grant’s hands a copy of Johnston’s orders.

Unknown to Grant, Johnston, on evacuating Jackson, marches north, halting for the night at Tougaloo, just north of Jackson. If he is seeking to join Pemberton, he is going in the wrong direction. On the 15th Johnston continues north as far as Calhoun, halfway to Canton, making the projected rendezvous with Pemberton more difficult.

Grant now turns west to confront Pemberton, who has come out toward him with a force of 23,000 men. The two armies meet at Champion Hill, seven miles east of the Big Black River.

Meanwhile, Pemberton has reached Edward’s Station from Bovina. An acrimonious meeting ensues with his generals. Pemberton holds that Johnston’s orders are contradictory to President Jefferson Davis’s instructions that “to hold both Vicksburg and Port Hudson is necessary to a connection with the Trans-Mississippi.” Pemberton wants to take position behind the Big Black with a bridgehead on the east side, and let the enemy assail him. We will repulse them, and then counterattack out of the bridgehead, he argues. His two senior generals—William W. Loring and Carter L. Stevenson—are unimpressed, and recommend that the army take the field in the morning, march southeast, and attack Union supply trains and reinforcements known to be en route to the enemy from Grand Gulf. Pemberton, despite misgivings, buys into his generals’ proposal. Orders are issued alerting the army to be ready to move out next morning, May 15.

There will be a five-hour delay while soldiers wait for rations and ammunition to arrive from Vicksburg and be issued. Two miles southeast of Edward’s Station, the Raymond Road crosses Baker’s Creek. The previous day’s cloudburst has caused the creek to flood. No one had checked the crossing to see if it was passable for infantry and artillery. Wirt Adams’s cavalry crosses on their horses, but when the infantry seeks to follow, the water is up to a tall man’s crotch and to a short man’s belly button. Pemberton is compelled to make a seven-mile detour by way of the Jackson and Ratliff roads to regain the Raymond Road east of the flooded Baker’s Creek crossing. He then pushes on and halts for the evening at Mrs. Sarah Ellison’s, where he and Loring spend the night. The long column halts along the road with the 400-plus wagon train bringing up the rear, parking at “the Crossroads” about daybreak on Saturday, May 16.

General Grant, on the 15th, moves to capitalize on his intelligence coup. Sherman remains in Jackson and wrecks the four railroads radiating into the town from the points of the compass. McClernand sends one division—Hovey’s—to Bolton, about 20 miles west of Jackson. Two other divisions—A. J. Smith’s (XIII Corps) and Frank Blair’s (XV Corps)—march from Raymond, taking the direct road to Edward’s Station, and McClernand with two divisions takes position on the Middle Road, midway between Bolton and Raymond. McPherson’s corps, with Grant in attendance, hastens west from Jackson, one division—Logan’s—halting near Bolton, and the other—Crocker’s—at Clinton. Unlike the Confederates, the Federals make easy marches on the 15th and camp early.

On Saturday morning a courier sent by Johnston, upon his May 14 evacuations of Jackson, reaches Pemberton at Mrs. Ellison’s with new instructions. Johnston reiterates his orders for Pemberton to pass to the north of Clinton and they will join forces and engage the foe. Time, however, is running out for Pemberton. Already east of Mrs. Ellison’s, on the Raymond Road, Wirt Adams’s cavalry supported by two infantry regiments has engaged the vanguard of one of Grant’s three columns.

You hear the boom of artillery as the messenger gallops up. Pemberton, although he is in contact with the enemy, orders his army to countermarch. What are the Rebels going to do? They hope to march back to Edward’s Station, where they will turn northeast into the Brownsville Road. The countermarch starts. It is a challenge to get the train turned around and start the wagons rumbling west escorted by Col. Alexander W. Reynolds’s brigade.

Now as the Rebels move out, what are McClernand’s orders? He is to advance cautiously and feel for the enemy. Grant does not want him bringing on a battle. The Raymond Road Yankees follow cautiously—A. J. Smith’s division is in front followed by Maj. Gen. Frank Blair’s two brigades. Confederate General Loring pulls back west of Jackson Creek and deploys his division on commanding ground on the Coker House Ridge. This is a good artillery position, clear gentle slopes in front, particularly if all the bluecoats are in that direction.

Then word comes from Champion Hill that the Yankees are also advancing on the Jackson Road. The Confederates are not prepared to meet this new threat. Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee—an Army of Northern Virginia veteran—sends a message to his division commander, Carter L. Stevenson, and tells him that he’s taking measures to cope with this situation. Lee leads his men up Jackson Road to the crest of Champion Hill. Here, at the crest, is a ridge extending to the northwest. Lee’s Alabamians file off and occupy this ridge.

Lee sees that the Yankees have reached Sid Champion’s house and are deploying. First to arrive are Alvin Hovey’s two brigades under Brig. Gen. George F. McGinnis and Col. James R. Slack. Artillery is unlimbered. Grant and McPherson come up from Clinton. Also reaching the area, at 10 a.m., is Black Jack Logan’s division. Logan takes position at a right angle on Hovey’s right with two brigades in advance. In reserve is John Stevenson’s brigade. McPherson’s other division, Crocker’s, having spent the night at Clinton, will not arrive on the field till mid-afternoon.

The bluecoats advance about 10:30. The Confederates by now have moved a second brigade up onto Champion Hill. Three of Brig. Gen. Alfred Cumming’s Georgia regiments take ground on Lee’s right, forming a salient and supporting four cannon. The crest of Champion Hill is bald. Two of Cumming’s regiments remain at the Crossroads faced east. They, along with four guns of Capt. James F. Waddell’s Alabama Battery, have the mission of holding the Crossroads against McClernand’s two divisions, who are cautiously feeling their way west, guiding on the Middle Road.

A second Georgia Brigade led by Brig. Gen. Seth Barton, accompanied by eight cannon, double-times into position on Lee’s left. The three Rebel brigades occupy commanding ground with cornfields to their front.

Pemberton’s three divisions as posted form a numeral “7.” Carter Stevenson’s three brigades on the left confront two Union divisions, and Bowen’s and Loring’s divisions on the right face four Union divisions who look to McClernand for orders. At this hour McClernand’s orders from Grant are unchanged: Move cautiously, feel for the enemy, and don’t bring on a battle. About noon Grant sends a staffer to McClernand with orders to attack. But instead of riding cross-country, the courier travels the roads, and more than two hours pass before McClernand learns that his mission has changed.

But the Confederates are in deep trouble long before McClernand receives his attack order. The Pennsylvania-born and -reared Pemberton carries lots of baggage. In the “Old Army” he had been a captain and Loring a colonel. Loring is “not a happy camper.” He doubts Pemberton’s capabilities. Brigade commander Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman supports this view. The two sit around that morning making “ill tempered jests” about Pemberton, recalls Lt. William A. Drennan.

By noon the Confederate defense of Champion Hill has unraveled. The Union two-division attack on three Confederate brigades is long remembered, and for the Confederates it is a nightmare. On the right John Stevenson’s reserve brigade is committed. Seth Barton’s Georgians crumble and flee, and the bluecoats capture eight cannon. On the Union left George McGinnis’s people guide on the Jackson Road. They reach the edge of the woods and halt less than 150 yards from the crest of the hill. Ahead is the salient held by Cumming’s three Georgia regiments and four cannon.

McGinnis reconnoiters and passes the word to load and cap their rifles. “When I give the signal start forward, then I’m going to chop my sword downward. We will then drop to the ground and the Confederates, when they fire, will overshoot.” It works! They come out of the woods, race forward, McGinnis chops his sword, and the soldiers go to ground. Confederate gunners pull their lanyards. Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! The Yanks leap to their feet, race forward, rout the Georgia regiments, and capture the cannon.

What is S. D. Lee to do? The Yanks have turned his left; they have turned his right. By bold leadership he holds his Alabamians together, and they fall back, step by step, into the Jackson Road. Colonel Slack’s men on McGinnis’s left storm toward the Crossroads, scatter the 56th and 57th Georgia, and capture Waddell’s four cannon. General Grant at his Champion House headquarters, upon being apprised of this sweeping success, sends a message, “Go down to Logan and tell him he is making history to-day.”

Approaching Vicksburg’s defenses from the east and northeast, Grant launched two unsuccessful assaults on the city—on May 19 against the Confederate Stockade Redan and on May 22 against a three-mile sector of the front extending from the 26th Louisiana Redoubt to Square Fort. Grant determined Vicksburg could only be taken by siege. As the siege progressed into summer, the Confederates suffered from disease and starvation, and the city’s residents were forced to seek shelter in caves and bombproofs from the daily bombardments by Grant’s artillery and Federal gunboats and mortar scows. By July 3 Pemberton asked for surrender terms, and on the following day Federal troops entered Vicksburg.

On the other side of the hill, Pemberton’s initial steps to confront disaster are gut-wrenching. He sends orders by a staffer for Bowen and Loring to hurry to Stevenson’s support. Bowen asks the aide, “What about the enemy to my front?” The staffer then questions Loring, and is told, “There are two Yankee divisions out there.” Bowen and Loring do not know until mid-afternoon that McClernand’s orders were to move cautiously.

Pemberton, on learning from his aide of the failure of his mission, rides off to see if he can get the two recalcitrant generals to respond to his orders to march to the left, where disaster threatens. Bowen responds to the crisis before Pemberton reaches him. He has pulled his two-brigade division off of the Jackson Creek line and is hastening to the Crossroads—the point of danger—via Ratliff Road. Bowen has waited almost too long. The situation is grim as Slack’s people, having secured the Crossroads, brace themselves to forge ahead.

Bowen, however, is closing rapidly with his more than 4,500 veterans. His command includes Col. Francis M. Cockrell’s Missouri Brigade. It has a combat record second to none. They lose more men in combat and fight in more battles than the famed Stonewall Brigade. As they come forward, Pemberton is a badly shaken man. I don’t know how Cockrell does it, sword in one hand and a magnolia in the other. They deploy in echelon, Cockrell’s brigade to the left of Ratliff Road; to the right of the road is Green’s brigade, also in echelon. They strike Slack’s men here, and his bluecoats skedaddle, headed north. Captain Waddell’s four guns—and the Crossroads—are back in Confederate hands. Onward they go, closing on the crest of Champion Hill.

Capt. James Mitchell of the 16th Ohio Light Artillery has advanced and unlimbers two cannon here. Nearby, out of action, are the four captured Confederate cannon. Mitchell sees panic-stricken bluecoats coming toward him, fleeing for their lives. Next he hears Rebel yells and then he sees Bowen’s people. The Buckeyes open with canister, but it is like trying to sweep back the tide with a broom. Storming forward, the grim Missourians and Arkansans kill Mitchell, capture his cannon, and send the Yankees in retreat down the north slope of Champion Hill. Grant, down at Sid Champion’s house, is concerned and sends his wagon train to the rear.

Fortunately Union reinforcements are approaching. They belong to Crocker’s division of McPherson’s corps. Marcellus Crocker is an Iowan. Forced to drop out of West Point because of tuberculosis, he returns to duty as a volunteer. A daring fighter, he tells his Third Brigade commander, Col. George B. Boomer, to deploy his men astride the Jackson Road near and south of Grant’s Champion House command post. This is difficult because coming toward them are frightened Yankees running for their lives. They break through Boomer’s ranks, causing problems. Unfortunately for the Confederates, they are running out of ammunition. As Bowen approaches, General Hovey masses 24 guns in the fields east of the Champion House. The Rebels crash into Boomer’s men, and the Yanks bend but do not break. Staggered and bloodied, the Confederates pull back. The bluecoats have met and mastered the battle’s final crisis.

Slowly but surely John Bowen’s dour fighters pull back. The crest of Champion Hill changes hands for a third and final time. As Crocker’s men forge ahead, McClernand’s bluecoats close on the Crossroads from the east. About 3 p.m. Loring belatedly starts for the Crossroads with two of his three brigades. Tilghman’s brigade and two batteries pull back from the Coker House Ridge to the next ridge, one-third of a mile farther west. Here they redeploy. The Federals advance and occupy the high ground at the Coker House, and call up 12 cannon. An artillery duel ensues on the Raymond Road front during which Tilghman dismounts to help sight one of his guns. He is killed by an enemy shell. His men, since the Federals to their front hold their ground, keep up a bold posture until recalled to rejoin Loring.

Meanwhile, east of the Crossroads, McClernand’s two Middle Road divisions finally receive Grant’s delayed attack order. The Confederates now face defeat. Preceded by Carter Stevenson’s shattered division, Bowen’s mauled command retreats southwest cross-country and fords Baker’s Creek at the Raymond crossing, the high water from the May 14 cloudburst having subsided. McClernand’s people spearhead the pursuit via the Jackson Road. Troops cross Baker’s Creek Bridge and turn toward the Raymond Road. They deploy and unlimber artillery and fire in a futile effort to intercept the Rebels as they head for Edward’s Station.

Most of Loring’s division does not ford Baker’s Creek, and Loring declines to run the gauntlet of artillery fire. He recalls those who have crossed and, guided by a local, turns his column down into the Baker’s Creek bottom. Several miles downstream Baker’s Creek converges into east-west flowing Fourteenmile Creek. Although the flood has subsided, the river’s bottom is boggy and the Confederates abandon 12 cannon, along with their caissons and limbers.

Early on Sunday, the 17th, Loring arrives at Whitaker’s Ford, south of Edward’s Station, and looking north, sees the glow of fires burning in the village. Loring decides to forgo rejoining Pemberton and heads for Crystal Springs.

Champion Hill is both the decisive battle and bloodiest engagement of the Vicksburg campaign. Union casualties number more than 2,400, while the Confederates list more than 2,800. This does not include the 3,000 stragglers lost by Loring’s division on its roundabout marches to join Johnston’s army.

Although Grant claims victory on May 16, he knows the campaign is far from over. He pushes westward, hoping to scoop up more Confederates before they make their way to the safety of Vicksburg’s fortifications. The two armies will meet again the next day at Big Black Bridge, with the Confederates hoping to stem the Union tide.

At Big Black Bridge, the Jackson Road and the Southern Mississippi Railroad converge. East of the river, Pemberton’s men had taken cotton bales and piled them up to build fortifications. Earlier Pemberton had wanted Grant to attack him here, so that he could counterattack out of the fortified bridgehead. Pemberton, on the morning of the 17th, has no idea about counterattacking. He doesn’t know that Loring is heading for Crystal Springs as fast as he can go. Bowen’s division, reinforced by Brig. Gen. John C. Vaughn’s Tennessee Brigade, recently arrived from Vicksburg, is across the Big Black along with 18 cannon. McClernand’s corps arrives in their front at 10 a.m. McClernand deploys three of his four divisions, from left to right A. J. Smith, Peter Osterhaus, and Eugene Carr.

Grant wants McClernand to pin the Rebels in position behind their breastworks east of the river; Sherman, who left Jackson on the 16th marching via roads parallel to and north of the railroad, will reach the Big Black at Bridgeport, north of the river’s big bend, and cross the river there. With Sherman is the army’s pontoon train. It is novel: Instead of wooden boats or canvas-covered collapsible craft, Sherman’s pontoons consist of large, circular rubber tubes that, when inflated by a large traveling bellows, are anchored athwart the river to support the sleepers and planks that form the bridge. McPherson plans to cross the river midway between Bridgeport and the Big Black Bridge.

Something goes wrong with Grant’s plan. The Union brigade commander on the right from Carr’s division is Brig. Gen. Michael “Big Mike” Lawler from County Kildare in Ireland. He leads men from Iowa and Wisconsin. Lawler weighs well over 250 pounds, but it’s all muscle. Big Mike, screened by trees, moves his men out toward the Big Black, which here flows through a deep trough between river and floodplain. Lawler puts them in that trough. Here they are invisible to the Rebels. He forms them in assault columns. At 11 a.m. he digs his spurs into his horse’s flanks and leads his Hawkeyes and Badgers out into the floodplain. The brigade sweeps forward and breaks the Confederate line. Colonel Cockrell looks up and sees what’s happened and yells, “Devil take the hindmost. Get out of here.”

The Confederates, in a matter of moments, break and run for the Big Black bridges. The Yankees capture 18 cannon; 1,700 to 1,800 cotton bales, which are salvaged and sent north; and more than 1,700 prisoners. Federal losses amount to 39 killed and 237 wounded. Prompt action by Confederate engineers, who torch the bridges, prevents McClernand’s corps from crossing the Big Black until the next morning.

This is another dark day in the history of Pemberton’s army. It was a mistake to await Loring’s return. As he rides back to Vicksburg, Pemberton is heard to remark, “Just 30 years ago I received my appointment to West Point and today that career is ended in disaster and disgrace.”

During the evening of May 17 and throughout the 18th, the retreating Confederates file into the nine-mile-long ring of fortifications guarding the land approaches to Vicksburg. Pemberton now has some 30,000 men to defend the city. Grant’s army of 45,000 is close on their heels; one more blow might finish off the disheartened Rebs—or so the Yankees believe.

Just north of the center of the Confederate line, guarding the Jackson Road, is the Third Louisiana Redan; a mile to the north, at the northeastern angle of the Vicksburg defenses, is Stockade Redan.

The forbidding Third Louisiana Redan is one of nine major Rebel forts. It is on Jackson Road Ridge, the highest point on the battlefield, approximately 400 feet above sea level. A redan is a triangular-shaped fortification. If it is enclosed, it has three angles and an equal number of fronts. South of Jackson Road is Great Redoubt. A redoubt is a rectangular or square enclosed fortification. While Great Redoubt is fronted by a ditch, Third Louisiana Redan is not. Why is it called the Third Louisiana Redan? It is garrisoned by the Third Louisiana Infantry. The units posted in this sector are led by Brig. Gen. Louis Hébert, a Louisianian. His brigade belongs to Maj. Gen. John H. Forney’s division. Forney’s people, like most of Maj. Gen. Martin L. Smith’s, have not engaged in the battles east of Vicksburg. Thus the Confederates who occupy the earthworks from Fort Hill, commanding the river on Pemberton’s left, to the Second Texas Lunette north of the Southern Railroad of Mississippi, have not tasted defeat.

The nine major works are connected by rifle pits or trenches. Battery lunettes, crescent-shaped earthworks to protect cannon, are sited at commanding positions along and behind the defense perimeter. Timber has been felled in the ravines and hollows, creating extensive abatis. These works had been laid out during the fall of 1862 and early winter of 1863. They had not been revetted—reinforced by an interior facing of timber or logs—nor had their surface been covered by sod. Loess soil erodes rapidly when it is disturbed, and heavy spring rains had caused extensive erosion. When the Confederates manned the works, they had lots of work to do to put them into condition and to mount artillery in the forts and lunettes.

Grant approaches on the afternoon of the 18th. Closing via Jackson Road is McPherson’s corps. Sherman follows Graveyard Road and McClernand’s corps marches on Baldwin’s Ferry Road. By evening only Sherman is in close. By late morning on the 19th, Sherman’s men are the only ones that are in contact with Confederate pickets.

Union morale is sky high. They have beaten the Confederates in five battles in 17 days. On the 16th they mauled Pemberton’s field army at Champion Hill. They routed the Confederates at Big Black Bridge. In these battles they inflicted more than 7,000 casualties on the foe; captured 65 cannon, and drove the Confederates back into Vicksburg, which seems ripe for plucking. The soldiers want to end it quick. Grant knows what a hot long summer on the river might do. Yellow jack—mosquito-borne yellow fever—or something equally atrocious might attack the Union forces. With scant preparation, Grant schedules an attack for the afternoon of May 19. The only serious fighting will be in the Stockade Redan section.

Stockade Redan is the strong point guarding the northeast approach to Vicksburg. Entering the Vicksburg works topping the ridge separating the headwaters of Mint Spring Bayou from the headwaters of Glass Bayou is Graveyard Road. Located here is Stockade Redan. Fronting Stockade Redan is a ditch or dry moat. Why is it called Stockade Redan? Across Graveyard Road is a poplar log stockade through which wagons can egress and ingress. To the west is the 27th Louisiana Redan, fronted by Mint Spring Bayou. Connecting the strong points are rifle pits. The Confederates here are fresh troops. They include the 36th Mississippi and 27th Louisiana.

Early on the 19th an event occurs that Sherman cites in his memoirs. When Maj. Gen. Frederick Steele’s division advances and secures Bell Smith Ridge, bounding Mint Spring Bayou on the north, driving in Rebel skirmishers, they sight smoke of Union transports and gunboats on the lower Yazoo River. They yell, “Hardtack! Hardtack!” Sherman recalls that the soldiers are tired of their diet of freshly slaughtered meat. He’ll turn to Grant and say, “You were right and I was wrong, because I thought you made a mistake when you marched south to cross the Mississippi rather than returning to Memphis and resuming the march down the railroad.”

This day you don’t want to be in Frank Blair’s division. It’s been a good division to be in so far. The men saw only skirmishing at Champion Hill, and they’ve seen no other action since their April 30–May 1 demonstration against Snyder’s Bluff. Blair gives his orders to attack. They’re going to have little or no artillery preparation. Col. Thomas Kilby Smith’s brigade guides on Graveyard Road. One of his regiments, the 55th Illinois, is led by Col. Oscar Malmborg, a heavy-drinking Swedish soldier of fortune. He’s unpopular with his men.

Steamboats occupy the wharves along Vicksburg’s busy waterfront. Vicksburg occupied a key strategic position on the Mississippi River for transporting goods between the Midwest and New Orleans.

On the ridges to the north Col. Giles A. Smith forms up his brigade. Among his units is a battalion of the 13th U.S. Infantry led by Capt. Edward Washington. The ravines where Mint Spring Bayou heads are filled with felled timber. Off to the northwest, on the far side of Mint Spring Bayou, there is the brigade led by Brig. Gen. Hugh Ewing, a friend of Stonewall Jackson back in today’s West Virginia. His men are new to the western army. They include the 37th and 47th Ohio and 4th West Virginia, veterans who have seen much action in western Virginia, and the 30th Ohio, which stood tall in the Antietam campaign. These newcomers with their kepis and paper collars are called “bandbox” soldiers by battered-hat wearing and raggedy-assed Westerners.

At 2 p.m. when Blair gives the word to attack, his men raise a “Huzzah!” They come forward in line of battle, elbow touching elbow. The second rank a step and a half behind the first, and then the file closers. As Kilby Smith’s people come under fire, the men enter the abatis on the left and right of Graveyard Road. In the abatis they get hung up in the felled timber. They halt, re-form, and drive forward. They reach a spur and a handful of men—mostly from the 83rd Indiana—dash forward and jump into the ditch. Those on the spur are pinned down. Unable to advance any closer to the Rebel works, they volley fire.

In the 55th Illinois is Drummer Orion Howe, a 14-year-old from Waukegan. Howe is a musician, young and agile. The soldiers fire up their ammunition fast, and they send men to the rear for more. Howe is among these volunteers. While sprinting along Graveyard Road, the lad is struck in the leg by a minié ball. Undaunted, he continues on his hazardous mission. Staggering up to a mounted Sherman, Howe informs the general of the crucial shortage of cartridges at the front. Impressed by the lad’s gallantry, the War Department awarded Howe the Medal of Honor on Sherman’s recommendation. He thus became one of the youngest recipients of the nation’s highest award for heroism.

Giles Smith’s line of advance is at a right angle to Kilby Smith’s. Surging first downward and then upward through felled timber, the bluecoats close on Stockade Redan’s north face. Particularly hard hit is the First Battalion, 13th U.S. Infantry. Among those out front is Color Sgt. James E. Brown. He is mortally wounded, and four others will likewise be cut down as they seek to advance the national colors. Battalion commander Washington is mortally wounded. Capt. Thomas Ewing, a Sherman brother-in-law, and ten men reach the ditch fronting the redan, but this is the Regulars’ high tide. Sherman calls the battalion’s performance “unequaled in the Army,” and authorizes the 13th to sew “First at Vicksburg” onto its colors.

The “bandbox” soldiers of Hugh Ewing’s brigade charge the 27th Louisiana Lunette, and it “looked for a while as if they would stay.” But in the end their battle line “went down in a windrow.” Grant’s May 19 assault has failed. Union casualties number 919, two-thirds of them belonging to Blair’s division. Confederate losses may have reached 200. Grant and his soldiers, much to their surprise, found that the Confederates, fighting behind earthworks, had recovered their self-confidence. It is evident that Vicksburg will not be captured by a poorly organized and uncoordinated attack.

Grant is determined to break through the Confederate lines. He gives his generals two days to plan an assault with all their forces to be carried out on May 22. Grant secures the cooperation of Admiral Porter’s gunboats, which will bombard the city’s defenses from the river. The day’s action will begin with a four-hour bombardment. As dawn breaks on the 22nd, the guns open fire.

Grant’s May 22 assault takes place in three sectors in this order: McPherson’s corps attacks north and south of Jackson road, Sherman’s centering on Graveyard Road, and McClernand’s south of the railroad. It will be an all-out assault. Grant has massed some 40,000 troops, and it will be up to the corps commanders how they will employ their soldiers. The plan is that at six o’clock in the morning all Union cannon will open fire. The bombardment will cease at 10 a.m. and be followed by the attack. Officers have synchronized their watches, perhaps a first.

On McPherson’s front, General Logan attacks with two brigades. John E. Smith’s forms in the ravine east of the Shirley House. The 23rd Indiana will lead the attack. When the artillery ceases fire, the Hoosiers come out of the ravine and onto Jackson Road in a column by eights. The Yankees surge onward, and as they pass through the deep cut, 100 yards west of the Third Louisiana Redan, the Rebels open fire and they take cover in the hollow north of the road. The Indianans are staggered. The regiment following the Hoosiers, the 20th Illinois, hunkers down in the ravine south of the road, and Smith’s attack is over. Out of Smith’s five regiments, he has engaged two.

John Stevenson is made of sterner stuff; he deploys as skirmishers the 17th Illinois in the hollow fronting Great Redoubt. When the artillery ceases fire, these units are to form into columns of assault. In the right column, eight abreast, are the 7th Missouri and 32nd Ohio. The left column, 200 yards to their left, includes the 8th and 81st Illinois. They start up the slope. The Rebels open fire. Men drop and they recoil into the hollow. Union artillery again hammers Great Redoubt. The order forward comes, and screened by skirmishers, the two columns again move up the slope. Col. James J. Dollins of the 81st Illinois is shot down and the left column breaks and recoils.

The right column, spearheaded by the Seventh Missouri, seems invincible as the regiment climbs the slope. An Irish regiment, the Missourians carry an emerald green flag. The vanguard, with a final desperate lunge, leap into the ditch fronting the redoubt and discover that their scaling ladders are too short. An engineer had goofed estimating the height from the bottom of the ditch to the top of the superior slope as 12 feet when it is 17. Trapped in the ditch, their advance is turned back with heavy losses.

Brig. Gen. Isaac F. Quinby now leads Crocker’s division, and he proves to be a timid soul. When his men cross a ridge 300 yards east of the Rebel works, they encounter a storm of canister and musketry and retire back having lost less than a dozen men. Of McPherson’s 32 regiments present only 7 have been seriously engaged—underscoring that perhaps as a combat commander McPherson’s leadership at Raymond had not been an aberration.

As it was on May 19, Sherman’s XV Corps today is on McPherson’s right. Less than 72 hours earlier the Confederates had savaged Blair’s people in the abatis-choked ravines flanking Graveyard Road. So, Sherman comes up with a “better idea.” A call goes out to Blair’s division for 150 volunteers, 50 from each of his three brigades. They are designated the “Forlorn Hope.” They will go forward carrying debris and scaling ladders. They will sling their rifle-muskets because they are going to come down the Graveyard Road eight abreast and they are not going to halt and fire. They will fill the ditch with the debris. The people coming behind are to charge over the debris and into the works. Following the Forlorn Hope is the brigade commanded by General Ewing in column by eights: the 30th Ohio, 37th Ohio, 4th West Virginia, and 47th Ohio. Behind them in the same formation are Blair’s other two brigades. Behind them are Brig. Gen. James Tuttle’s three brigades. You’ve got a battering ram that beats all battering rams. Almost 10,000 men, eight abreast, extending back along Graveyard Road for more than a mile.

The bombardment ceases at 10 a.m. Ewing looks at Capt. John Gorce, commanding the Forlorn Hope. Gorce bellows “Forward!” Pvt. Howell Trogden carries Ewing’s headquarters flag, and down the road they come. The Confederate works are enveloped in dust and smoke. The Yanks hope that the artillery has solved everything. You hear the shuffling of their feet. When they reach the Graveyard Road cut, 100 yards from Stockade Redan, the dust and smoke clears, and a terrible sight appears: Rebels in two ranks come into view. They fire a crashing volley. Dead and wounded fall. Gorce and Trogden get into the ditch with a handful of men and plant Ewing’s headquarters flag on the exterior slope.

Up comes the 30th Ohio. The Buckeyes see dead and wounded sprawled in the cut. They enter the cut and suffer a fate similar to the Forlorn Hope. Dead and wounded are cut down, and a handful of men surge onward and reach the ditch. Now comes the 37th Ohio, raised from in and around Toledo. The men enter the cut, see dead and wounded, freeze, and either go to ground or take cover in the ravines to the left and right. Col. Lewis von Blessing and Sgt. Maj. Lewis Sebastian, in a futile effort to get the attack moving, employ their swords upon the shirkers’ backsides.

Sherman’s attack is stymied. He has only committed the Forlorn Hope, and the 30th and 37th Ohio. Sherman will do nothing more until noon. Grant has joined him. Here Grant receives a message from General McClernand reporting, “We have part possession of two forts, and the stars and stripes are floating over them.” Grant believes McClernand is exaggerating. But he can’t let the opportunity pass. So he orders the attack renewed. General Quinby sends his division to reinforce McClernand at the Railroad Redoubt and the Second Texas Lunette, and Sherman will again assail Stockade Redan as well as the earthwork west and south of that salient angle, where the Missouri monument now stands.

Sherman launches four attacks during the afternoon. They are piecemeal and uncoordinated. At 1 p.m. Brig. Gen. Thomas E. G. Ransom’s brigade, of McPherson’s XVII Corps on Sherman’s left spearheaded by the 14th and 17th Wisconsin and 72nd Illinois, charges up and out of the north prong of Glass Bayou. They close on the enemy’s works but are thrown back. About a half hour later the brigades of Giles Smith and Kilby Smith are repulsed. Let’s try what we did in the morning: Send another column down Graveyard road. Let’s do it with Brig. Gen. Joe Mower, he’s a helluva fighter, and commands the famed Eagle Brigade. “Old Abe,” the Eighth Wisconsin’s war eagle, is a much honored bird, but never soared above a battlefield because he is chained to his perch, which is carried next to the colors.

The brigade comes forward in column by eights. The 11th Missouri, Col. Andrew Weber commanding, leads off, followed respectively by the 47th Illinois, 8th Wisconsin, and 5th Minnesota. A handful of men accompanied by Colonel Weber of the 11th Missouri gain the ditch fronting Stockade Redan, and now two flags fly on the exterior slope of that work. Just as Old Abe enters the cut and is about to be blasted into eternity, Sherman looks at Mower, Mower looks at him, and they suspend the attack.

At four o’clock, at a point three-quarters of a mile west of Stockade Redan, General Steele finally gets his men into position. Up the steep slope they charge, but are repulsed. Sherman’s May 22 attack has failed.

On McClernand’s front to the south, the initial Yankee assaults against Second Texas Lunette and Railroad Redoubt fare better.

Railroad Redoubt juts out in front of the Confederate works. It is garrisoned by a detachment of the 30th Alabama, commanded by Col. Charles M. Shelley, one of five regiments in S. D. Lee’s Alabama Brigade. Two cannon are emplaced in the work. To the north of the railroad, the Second Texas defends the lunette that bears the regiment’s name.

McClernand has six brigades available for his attack. He places Eugene Asa Carr in command of the four brigades on the right. Carr assigns the brigades under Brig. Gens. Stephen Burbridge and William P. Benton to attack the Texans, and the two led by Mike Lawler and Col. William Landram to assail Railroad Redoubt.

Col. George Bailey’s 99th Illinois heads Benton’s column as it emerges from the ravine fronting today’s visitor center and crosses Baldwin’s Ferry Road. Bailey strides along in his shirtsleeves. Alongside him is one of his color bearers, Cpl. Thomas J. Higgins. Higgins rushes into the Rebel fire and doesn’t look back. He goes into the foe’s works and Texas Capt. A. J. Hurley pulls him in, grabs his chest, and inquires, “Are you wearing a bulletproof vest? My men are good shots. They were shooting at you.” Higgins looks around. Where in the hell are his friends? He looks to the rear and sees that Bailey and the rest of the 99th have gone to ground.

But on come many more Yanks and after a desperate struggle finally gain the ditch fronting Second Texas Lunette. The lunette’s interior traverses are bales of cotton and they catch fire. The Federals seek to crawl through the cannon embrasures. The Confederates throw them back. You’ve got bluecoats in the ditch and the Texans in the lunette. The Chicago Mercantile Battery under Capt. Patrick White, who along with five of his cannoneers become recipients of the Medal of Honor, push a brass six-pounder to within ten yards of the works. They begin pumping shots into the lunette.

South of the railroad a dozen Iowans led by Sgts. Joseph Griffith and Nicholas Messenger fight their way into Railroad Redoubt and drive the Rebels out. The Confederates counterattack. Hiding behind a traverse is Lt. J. M. Pearson and a score of Alabamians. Capt. H. P. Oden leads about 15 counterattacking Alabamians. As they enter the work, they see both Yanks and Rebels. The Johnnies are crouched down. Oden screams at Pearson, “Why in the hell ain’t you fighting?” The Iowans fire. Oden and most of his men are killed or wounded in falling back. Pearson and his men ground arms and surrender.

The Iowans plant their colors in the redoubt and are soon reinforced by soldiers of the 77th Illinois. Unlike McPherson and Sherman, who have many men on the field but not in contact with the foe, McClernand and Carr have all their men engaged. They have no reserves to exploit the situation. The Confederates have reserves, the men of Bowen’s division. Bowen sends Cockrell’s Missourians to support the Stockade Redan defenders, and Green’s brigade to bolster the Texans at the lunette. This leads to a stalemate on McClernand’s front.

To break the impasse, McPherson sends Quinby’s division. Instead of deploying the fresh division as a unit, McClernand breaks it up. Col. John C. Sanborn’s brigade rushes to support Benton and Burbridge at Second Texas Lunette. Col. George B. Boomer is to reinforce Lawler and Landram at Railroad Redoubt. Col. Samuel Holmes goes to Square Fort to help Osterhaus’s division.

It’s 3 p.m. and yes, the Yanks still hold Railroad Redoubt and are in the ditch fronting Second Texas Lunette. The Confederates see Boomer forming his men. Brigade commander S. D. Lee knows he’d better drive those Yankees out of the Redoubt, or Boomer’s bluecoats might punch through the Confederates’ second line. He calls on Colonel Shelley for a counterattack, but Shelley refuses.

Now comes up a hero. Col. Thomas Waul had been a Vicksburg lawyer before going to Texas. He had raised Waul’s Texas Legion and solicits for his Texans the honor of recapturing the Redoubt. Lee tells him to proceed. Two companies of Texans guided by Col. Edmund Pettus counterattack. They overwhelm the Yankees, capturing several flags. Down in the ditch fronting the works is Lt. Col. Harvey Graham with about 70 bluecoats. S. D. Lee rolls 18-pound shells down into the ditch. Soon Colonel Graham and his men ground their arms. The breach is sealed.

Too late, Boomer’s men advance. The Confederates open fire and he’s almost the first casualty. With Boomer mortally wounded his men drop to the ground. What’s happening at the Second Texas Lunette? Up comes Sanborn’s people. Burbridge’s and Benton’s troops have been here all day. As soon as the reinforcements come up, they pull out. To make a grim situation worse for Sanborn’s newcomers, Green’s Arkansans and Missourians sortie. Orders now come to retire. But before Sanborn does, Federal infantrymen help Captain White withdraw his brass six-pounder, which had been manhandled to within a few yards of the ditch fronting the lunette.

McClernand’s soldiers are back where they were in the morning, the same as Sherman’s and McPherson’s. Losses on his front were much greater, though at one time his corps had secured part possession of Railroad Redoubt and gained the Second Texas Lunette’s ditch. The great assault is over. There are 3,199 Union dead, wounded, and missing, of whom about 500 are prisoners. Five stands of colors are captured. Confederate losses do not exceed 500.

Thwarted in his efforts to take Vicksburg by assault, Grant decides to besiege the Confederate city. Union soldiers entrench; in various places they begin to dig approaches—zigzag trenches that push toward the Confederate fortifications.

Gen. Alvin Hovey’s approach is directed against Square Fort. The Yankees position two sap rollers—huge wicker cylinders that can be rolled ahead of men digging a trench for protection against enemy fire. They dig two approach trenches that zigzag up these spurs. There are many Union sharpshooters. After May 22 you have a better chance to be killed or wounded if you are a Rebel. You ask, Why does that happen? The Rebs are entrenched. The Yanks aren’t dug in as well. Where are the Confederates? They are on the high ground. Where do you expose yourself as a silhouette? On the high ground.

Where would you like to be if you are a Yankee marksman? You’d like to be on the low ground with sandbags in front of you or behind a tree, waiting all day until some Confederate exposes himself on the skyline. Because of optics, whether you are a Civil War soldier or a World War II combat infantryman, the human eye is such that if you fire down a grade your optic nerve tends to make you fire high. That is why the officers and NCOs when Civil War soldiers fought in line of battle kept yelling “Fire low. Fire low.” If you fire at a man’s knees you are probably going to hit him in the middle, if you aim high, the odds are that you will miss.

Particularly at risk are senior officers. Among those gunned down are brigade commanders—Col. Isham W. Garrott of the 20th Alabama is killed in Square Fort on June 17 by a Union sharpshooter, and Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green of Missouri on June 25. Subsequent to the two officers’ deaths, Square Fort is designated Fort Garrott and a smaller work at the Missouri Monument Green’s Redan.

Elsewhere the Yankees try other ways to breach the Confederate defenses.

Lt. Henry C. Foster of the 23rd Indiana gets revenge on the Confederates for what they did to his regiment on May 22 and earlier at Raymond. He and his men use railroad ties to construct a tower. The tower is built on commanding ground south of Jackson Road, adjacent to Logan’s Approach, and is raised to a height sufficient to allow Foster to see over the Third Louisiana Redan’s parapet. Foster, because of his marksmanship, became a terror to the Confederates. Among the Yanks in Logan’s division, because of his coonskin cap, he became known as “Coonskin” Foster and his perch as “Coonskin Tower.” He is visited here on one occasion by Ulysses S. Grant.

All the while the Federals continue digging and pushing Logan’s Approach, which began in the hollow at the Shirley House closer to Third Louisiana Redan. As they dig, sappers push a railroad flatcar stacked with cotton bales ahead of them. In a successful effort to slow the Yanks, Col. Sam Russell of the Third Lousiana calls for smoothbore muskets. He then secures tow (refuse cotton), soaks it in turpentine, wraps it around small-caliber musket balls, and has his men fire these into the cotton bales. The sap roller catches fire and burns. But Logan’s people improvise. What do they do? They get several 55-gallon barrels, nail two of them together, fill them with dirt, and then wrap them with cane. This gives them a mobile barricade ten feet wide and five feet high that is not flammable.