MAY 5–6, 1864

On March 9, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln handed Ulysses S. Grant his commission as a lieutenant general, and within days Grant took command of the armies of the United States. The President had decided to place Grant in overall command in the hope that the hero of Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Missionary Ridge could crush the rebellion—or at least achieve sufficient success to guarantee Lincoln’s reelection—so that the war would be fought to ultimate victory.

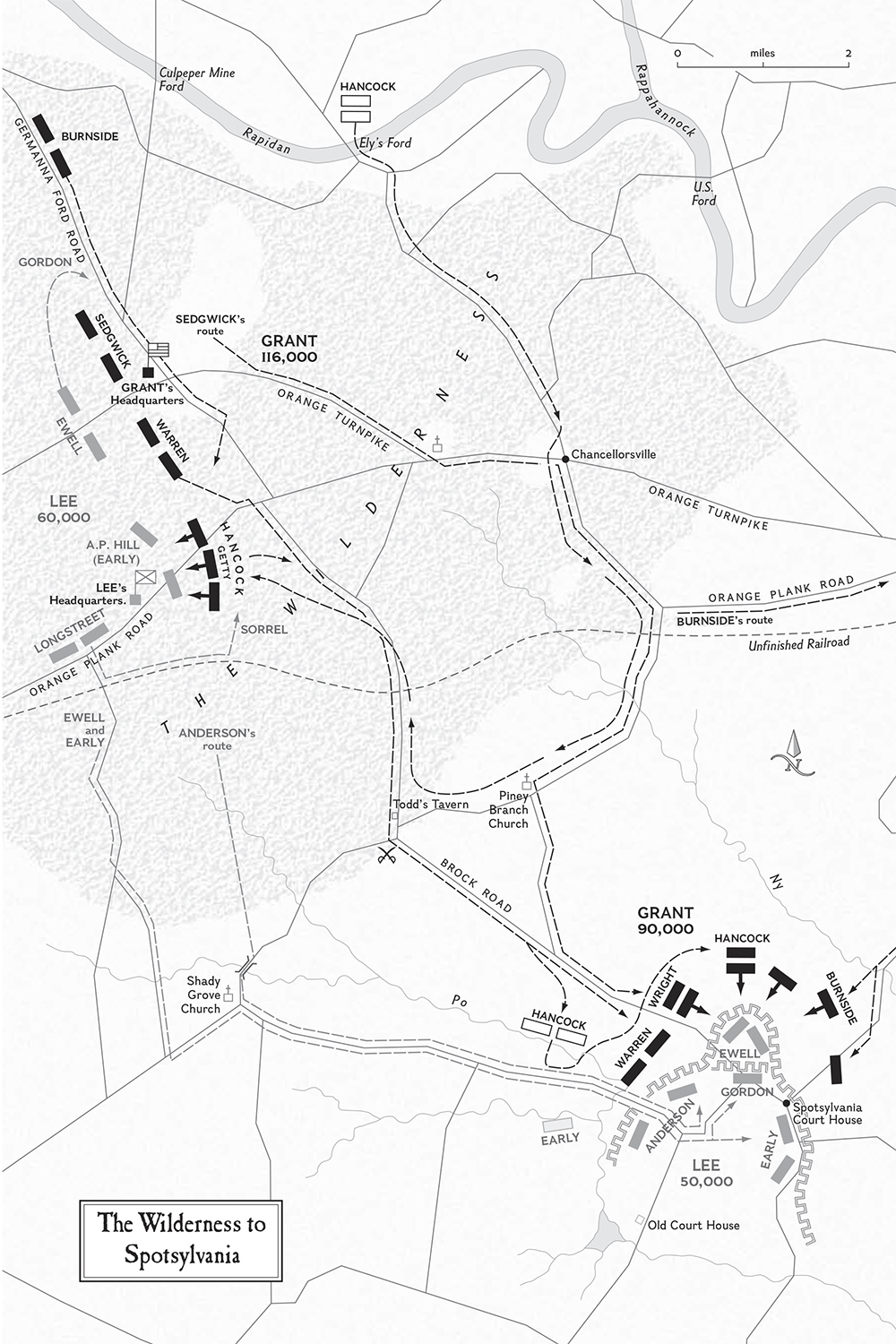

Grant decided to turn over command of operations in the West to his trusted subordinate Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. He planned to stay in the East and oversee the operations of the Army of the Potomac and other forces against Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. For the spring of 1864 he had mapped out an offensive plan on four fronts. One Union army, 8,900 men under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, would advance southward up the Shenandoah Valley; another would operate in southwestern Virginia; a third force, the Army of the James under Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, would travel up the James River toward Richmond and threaten the Confederate capital, looking either to capture it or cut it off from the Confederate heartland. Grant would accompany Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac and direct the operations of Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s separate IX Corps. Grant employed more than 116,000 men against his target, the 65,000 men of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

After Gettysburg, Union and Confederate armies had continued to maneuver against each other, sparring around Culpeper and the heavily fortified Confederate lines behind Mine Run, a tributary of the Rapidan. Neither side could gain the advantage, and both armies settled into an uneasy truce for the winter. In September 1863, Lee had sent Lt. Gen. James Longstreet with two divisions of his corps west by rail to reinforce the Army of Tennessee. Longstreet’s men fought at Chickamauga and Knoxville before returning to Virginia in mid-April 1864. The Army of Northern Virginia spent the winter south of the line of the Rapidan River in the Virginia Piedmont; the Yankees remained north of the river with their winter camps located in Culpeper County and around Warrenton.

Grant proposed to cross the Rapidan, march southeast through the Wilderness, and then turn west to confront Lee, forcing him to fight on open ground. He looked for Sherman to commence his operations in northern Georgia the same week. So once more, as in years past, a new Yankee commander would match wits with Robert E. Lee, who had yet to lose a campaign conducted on Virginia soil. The Wilderness is a 60-square-mile region of played-out tobacco land, cut over in the 18th and early 19th century. The region had grown up in dense scrub, and brush-choked fields were intersected by tangled, wooded creek bottoms. Roads and a few hardscrabble farm fields provided rare openings in an otherwise impenetrable landscape. Grant planned to use the Wilderness to shield his movements, but hoped to march through it quickly before confronting Lee.

The Union Army broke camp at dusk on May 3. They marched southeast to cross the Rapidan River; three-quarters of the Army of the Potomac’s 116,000 men and thousands of horses and mules will cross at Germanna Ford. In front is a cavalry division under Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, a Grant protégé who has been promoted and transferred from staff to line; it clears away the few Confederates in the area and secures the crossing. The engineers arrive and commence positioning two pontoon bridges. They’ll also build two bridges down at Ely’s Ford, five miles downstream, and one at Culpeper Mine Ford.

Troops of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s VI Corps cross the Rapidan River at Germanna Ford on May 4, 1864, advancing into “the Wilderness,” a stretch of tangled brush and woods west of Chancellorsville.

Wilson’s cavalry pushes on to the Wilderness Tavern, located at the crossroads of the Germanna Plank Road and the Orange Turnpike. Behind him the infantry commences crossing the river. First to cross is Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Kemble Warren’s V Corps. By early afternoon on May 4 the last man of V Corps is across. They are followed by VI Corps. Grant and Meade establish their command posts on the high ground near the ford. It will be May 5 before Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps marches all the way from Warrenton Junction to cross the river. They’ll then take up one of the pontoon bridges, leaving the other in place.

As Warren’s men cross, soldiers see Elihu Washburne traveling with Grant’s staff. The Illinois congressman wears severe black clothes. The soldiers speculate that this is going to be a bad campaign, because he looks like Grant’s personal undertaker. One of Meade’s aides, Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, wonders if every man that crosses those bridges who is to become a casualty in the next six weeks would wear a badge, what would it look like? If so, nearly half of those men who are crossing here would have a badge. In six weeks, half of those men will become casualties.

Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps is crossing downriver at Ely’s Ford. A portion of Grant’s supply trains also crossed at Ely’s while other wagons crossed at Culpeper Mine Ford, between the two wings of the Federal forces. But the wagon trains cannot cross in an expeditious manner. So nightfall on May 4 finds Warren camped at Wilderness Run and Ellwood, 12 miles short of Spotsylvania Court House. Hancock, with his vanguard, has reached Chancellorsville, where the gaunt walls of the Chancellor House stand, fire-blackened from the conflagration that destroyed it just one year earlier on May 3, 1863. Hancock’s here by 10 a.m. with the vanguard, but they can’t move on. Grant’s plan to get through the Wilderness in one long day’s march has unraveled. They cannot leave the more than 5,500 wagons. They’re part of the army’s trains and can’t get across the river that day, and responsible Federal officers are worried that Rebel cavalry may sweep down on and maul the wagon trains. If you put all those wagons on one road, the line would reach from Richmond to Washington, D.C. It’s a logistician’s nightmare.

Lee is already responding. Approaching along the Orange Turnpike, seven miles west of Wilderness Tavern, is Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s corps. About 12 miles off, along the Orange Plank Road, is Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill’s corps, with Lee present. They march east to intercept the Yankees. Think of the Union columns as twin snakes moving southeast through the Wilderness; Lee wants to strike the columns and cut them in two. Longstreet has the farthest to go. He has marched at noon from Gordonsville and is still more than 25 miles away on the night of May 4. If Ewell’s people reach Wilderness Tavern and get astride the road, he will cut the Federal snake in two; if Hill reaches the intersection of the Orange Plank and Brock roads first, that snake will be cut into three parts.

As morning dawns on May 5, Grant intends to continue moving southeast, hoping to get through the Wilderness before turning west to face Lee. The general in chief decides to establish headquarters near Wilderness Tavern. Some two miles away to the west Federal skirmishers spot Ewell’s advance.

Saunders Field is one and a half miles west of Wilderness Tavern astride the Orange Turnpike. It is owned by an absentee landowner, Horatio Allen from New York City. Saunders was his tenant, but he has not raised a crop here in two years. The turnpike was much narrower then than it is now. It is a macadamized or gravel road.

On May 4, Wilson’s Union cavalry rides west along the turnpike to Locust Grove, several miles away. Instead of leaving a strong force here to guard the turnpike, Wilson takes his division south to Parker’s Store and beyond. Approaching on the turnpike are 17,000 Rebels led by Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division. Headed east on the Orange Plank Road to the south are about 22,000 eager Confederates of A. P. Hill’s corps spearheaded by Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division. If Grant keeps moving through the Wilderness, he will have his army cut into three parts. If Longstreet comes in on the Catharpin Road, which parallels the Orange Plank Road to the south, it could be severed into five parts.

That morning, Warren starts V Corps, spearheaded by Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford’s division, down a country road that leads from Ellwood by the Chewning Farm to Parker’s Store. He is to be followed by the divisions of Brig. Gens. James S. Wadsworth and John C. Robinson. Before Robinson can move out, word is received that the Rebels are approaching via the Orange Turnpike in force. These are the men of Ewell’s corps—the divisions of Maj. Gens. Edward Johnson, Jubal A. Early, and Robert E. Rodes.

Trigger-tempered Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin is ordered to take his First Division, some 5,000 strong, and march west along the turnpike to engage and block Ewell. When he reaches the east side of Saunders Field, the Confederates have gained the west edge of the field and are deploying. He asks for instructions and is told to attack; he is promised by Warren that Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s VI Corps will provide support on the right. Sedgwick has turned the head of his column off the Germanna Plank Road and is cutting southwest, marching along the narrow Culpeper Mine Road, which runs into the Orange Turnpike, but Sedgwick is a long way off and isn’t going to get into the area until late afternoon. His march will be slowed by Rebel skirmishers and cavalry.

Griffin’s division attacks the Confederates to his front, and it isn’t going to be enjoyable. It starts as fun for the Yankees, but it turns into a disaster. Brig. Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres’s brigade deploys north of the pike. Out in front is the 140th New York along with seven battalions of regulars. In support are the 146th New York and the 91st and 155th Pennsylvania. Like the 140th New York, these three regiments wear variations of the Zouave uniform. South of the road is everybody’s favorite regiment, the 20th Maine. It is in Brig. Gen. Joseph J. Bartlett’s brigade, along with the 83rd Pennsylvania and 44th New York. Like many of Ayres’s men, they are veterans of the struggle for Little Round Top. Two other regiments also join the group. They are supported by a third brigade, Col. Jacob B. Sweitzer’s.

Griffin knows the Rebels are in the woods entrenching. He protests to Warren his attack orders. Warren reiterates his orders, which he got from Meade, to assail the enemy to your front. He again promises Griffin that he’ll be supported on the right by Sedgwick and on the left by the Iron Brigade of Wadsworth’s division. So Griffin advances. Col. George Ryan of the 140th New York loses his sword as he dismounts and uses his hat to gesticulate as he leads his men forward. They surge through a swale angling across Saunders Field; confronted by thickets, the regulars diverge to the right, opening up a gap in Ayres’s line.

Five hundred and twenty strong, the New Yorkers ascend the slope and attack the Confederates on the west edge of Saunders Field. For 30 minutes they cling to a foothold in the woods, but they lose half their men—killed, wounded, or captured. Then the second wave comes forward—the 146th New York and 91st and 155th Pennsylvania. Like the 140th, they are repulsed because they have no support on their right. Sedgwick, as promised by Warren, has not come up.

The Confederates have thrown up breastworks back about 20 yards in the woods along the western side of the field. Johnny Rebs move up to the edge of the woods to fire at the bluecoats. When the New Yorkers top the first rise beyond the midfield swale, the Rebels really give them hell. First the 140th and then the 146th New York give way. To their right the regulars and the two Pennsylvania Zouave regiments are hammered by Brig. Gen. George “Maryland” Steuart’s brigade of Virginians and Tarheels and by Brig. Gen. James A. Walker’s Stonewall Brigade. By 2:30 p.m. the only Yankees left in Saunders Field are dead and wounded. The rest retreat back into the woods to the south and east, abandoning two cannon manned by redlegs of the First New York Artillery, Company D, as they flee.

News for the Federals is not much better south of the turnpike, where Bartlett’s brigade attacks Brig. Gen. John Marshall Jones’s Virginia Brigade.

The Confederates are positioned along high ground south of the turnpike, entrenching, when Bartlett’s brigade breaks hard-drinking Jones’s brigade, killing Jones, and sweeping everything before them. But as they advance, they find that Ayres’s repulse has left their right flank vulnerable to fire from north of the turnpike. Worse, some 300 yards on the far side of a ravine to their front is Brig. Gen. Cullen A. Battle’s Alabama Brigade. These are the first people of Gen. Robert E. Rodes’s division to come up to reinforce Johnson’s lead division. Bartlett believes they are carrying everything before them as they press onward, driving Jones’s men before them like chaff. They then run into a counterattack. Ayres has been bested, two cannon abandoned, and the Alabamians are on their flank. Worse, Wadsworth’s division, with the Iron Brigade in front, on its left has encountered more of Rodes’s units—Brig. Gens. George Doles’s and Junius Daniel’s brigades. Bartlett is isolated; his brigade collapses and flees into the woods east of Saunders Field. The situation looks bleak for V Corps.

On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River into the Wilderness and collided with Lee’s forces on May 5, leading to a day of fierce but inconclusive fighting in the tangled thickets. At dawn on May 6 the Federals renewed their attack, but by the end of the day the Confederates had checked the Federal assaults. Grant continued his advance on May 7, moving around Lee’s right only to be blocked by the Rebels on May 8 at Spotsylvania Court House, beginning two weeks of brutal combat. On May 21, Grant broke off the fight and continued his advance on Richmond.

Griffin is beside himself. No support on his right. Where is Sedgwick? Griffin has received preemptive orders to attack and he has met disaster. He rides to the rear blazing with anger. As he rides up to army headquarters, he speaks harshly of decisions such as this. He denounces General Warren because he’s the guy who gave him the orders. His rage bounces up the command chain. Dismounting, Griffin ignores Grant. Addressing Meade, he curses Warren and Sedgwick for their actions. Meade does not respond, and Grant’s chief of staff, John Rawlins, shakes his head as Griffin turns his back and walks away.

Grant is shocked and inquires of Meade, “Who is this General Gregg? You ought to put him under arrest.” Meade, known as “Old Snapping Turtle,” is the only cool officer present. He sees that Grant’s coat is unbuttoned. He steps up to Grant, buttons his coat, and says, “His name is Griffin not Gregg, and that’s only his way of talking.” That momentarily calms the passions that have been aroused at Grant and Meade’s headquarters.

About a mile south of Saunders Field, at the Higgerson Farm, savage fighting has erupted. One of the Confederates’ advantages is that they know the terrain, including the lay of the land, the ground cover, and ways to get around quickly. If they can find and get on the Union flanks, they can shatter the Yankees.

General Wadsworth is a non-West Pointer from Genesee, New York, and one of the wealthiest men in the North. He has three brigades. North of Wilderness Run in the woods is a popular unit both then and now, the Iron Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler. Moving through the Higgerson Farm, somewhat unable to keep abreast of Cutler on their right, are Col. Roy Stone’s four Pennsylvania regiments. They’re beating their way through the underbrush bounding a branch of Wilderness Run. On their left, moving faster, is Brig. Gen. James C. “Crazy” Rice’s brigade.

The Confederates send two brigades from Rodes’s division into this area. North of Wilderness Run, confronting the Iron Brigade, are Doles’s Georgians; south of the creek, Daniel’s North Carolinians attack Rice. From Jubal Early’s division, the Confederates rush a brigade, six regiments of Georgians, led by Brig. Gen. John Brown Gordon, to engage Stone.

Permelia Higgerson is unhappy when the bluecoats come through her garden, and she threatens retribution. Retribution comes soon. Gordon’s men strike the Union center, held by Stone’s Pennsylvanians. The Federals break. That exposes Rice’s men on Stone’s left and the Iron Brigade on his right. The situation is critical. General Crawford at the Chewning Farm is ordered to send four of his Pennsylvania Reserve Regiments through the woods to try to plug the gap that has been ripped in the Union line.

Now, we get a great human-interest story. As the Yankees pull back, the Seventh Pennsylvania Reserves is isolated in a thicket. Maj. James D. Van Valkenburgh of the 61st Georgia, who had been captured by the Pennsylvania Reserves at the Battle of Fredericksburg and then exchanged, is maneuvering with just one company of men. He doesn’t know who is in front of him, but he demands that unit’s surrender. Realizing they are isolated, but not cognizant that they are confronted by fewer than 35 or 40 Confederates, the Seventh Pennsylvania, almost 300 strong, surrenders. The poor folks in the Seventh Pennsylvania aren’t very lucky. Grant has issued an order ending the exchange of prisoners; they are fated to be sent to that “wonderful rest camp” in Georgia known as Andersonville. There 270 of them will see more than 90 of their comrades die.

The news for the remainder of Samuel Crawford’s division, a mile south of the Higgerson Farm at the Chewning Farm, is not much better.

Samuel Crawford is in charge of the Pennsylvania Reserves; they are advancing toward Parker’s Store, located to their south on the Orange Plank Road, where James Wilson left the Fifth New York Cavalry when his division rode south to scout the Catharpin Road. Near Parker’s Store the cavalrymen soon find themselves confronting the advance of Henry Heth’s division, five North Carolina regiments commanded by Brig. Gen. William Kirkland, spearheading A. P. Hill’s corps.

What is Crawford going to do? He is isolated. He has several options if he is a great general. One is to attack the Confederates in the flank, or he can reinforce the Fifth New York Cavalry. He opts for the latter, but sends only one regiment: the 13th Pennsylvania Reserves, armed with repeating Spencer rifles. Spencer rifles might be useful, but they are not that good when one’s outnumbered more than five to one. He could also pull back. He stays at Chewning’s, and soon finds himself in a difficult situation. He gets a call to rush reinforcements to the fight at Higgerson Farm. Next Wadsworth warns Crawford that he is in danger of being cut off unless he withdraws to Ellwood, which he does.

With Crawford no longer threatening their left flank, A. P. Hill’s men march east along the Orange Plank Road. If they reach the intersection of Brock Road, they’ll occupy ground between the Yankee V and II Corps and split the Union Army in two. Hancock turns and races north from Todd’s Tavern toward the junction to prevent that. So does Brig. Gen. George W. Getty, a division commander in Sedgwick’s VI Corps.

It looks bleak for Meade’s Army of the Potomac. The Fifth New York Cavalry is pushed back by Kirkland’s Tarheels, and there are many more Confederates behind them: Henry Heth’s division, 6,000 strong, is backed by Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s division. Arriving at the intersection of Orange Plank and Brock roads on a march from Wilderness Tavern are three VI Corps brigades led by Brig. Gen. George W. Getty. Getty rides up with his staff; they dismount and strive to buy time until their division comes up. Finally the brigades appear. Col. Lewis A. Grant’s Vermont Brigade anchors the left flank fronting along Brock Road south of the Plank Road; the other brigades—Brig. Gen. Frank Wheaton’s and Brig. Gen. Henry L. Eustis’s—are posted north of the Plank Road. Getty gets his people in position just in the nick of time and keeps the Confederates from occupying this crossroads and cutting the Union Army in two. But General Grant wants more men at this key point, having resolved to fight Lee in the Wilderness.

Hancock’s four-division corps has marched via the Plank and Catharpin roads from Chancellorsville en route to Shady Grove Church, about six miles west of Spotsylvania Court House. By early afternoon he has reached two miles beyond Todd’s Tavern. Here he is halted and ordered to countermarch back to the Brock Road, and follow that road north to its intersection with the Plank Road.

Hancock’s men are the “Bully Boys” of the Army of the Potomac. They not only think they’re good—they know that they’re good. It’s mid-afternoon when they begin arriving at the strategic crossroads. Wilson’s cavalry is left near Todd’s Tavern to guard the intersection of the Shady Grove Church and Catharpin Roads. First up is Maj. Gen. David Birney’s division. Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays’s brigade goes into position north of the road. You do not want to be in Hays’s brigade. He will lose more than half his men here. Hays is a Grant favorite. The friendship goes back to West Point, Hays being one year behind Grant. Hays is big, even then. Grant is small. Grant owes him a few favors from West Point for protecting him from bullies.

Confederate breastworks in Saunders Field, located along the Orange Turnpike west of Wilderness Church, site of a major engagement during the Battle of the Wilderness.

Now, there are two schools of thought regarding Hays’s character. His old II Corps people think he is great. The men who have been integrated into Hancock’s corps from the disbanded III Corps view him as a loudmouthed drunk and braggart. Meanwhile, Brig. Gen. Gershom Mott’s Fourth Division comes up and takes position south of the Orange Plank Road to bolster the Vermont Brigade. The bluecoats now have numbers on their side: One division of VI Corps, two divisions of II Corps, and soon Brig. Gen. John Gibbon arrives with another division.

Hays leads his men in, brandishing his sword, and a bullet strikes him in the temple. Grant takes his death hard. The fighting ebbs and flows. Wilcox’s four brigades enter the battle in support of Heth. Slowly the Yankees begin to gain the upper hand. Numbers tell. Moving south from Ellwood is General Wadsworth. He has re-formed his V Corps division. Here fortune smiles on the Confederates.

As Wadsworth brings his men forward he bears in on the Confederate left flank. Lee’s only reserve is the Fifth Alabama Battalion, 250 strong. But, in the woods, you don’t know whether they are 250 or 2,500. The Fifth Alabama Battalion strikes Wadsworth’s men in the flank, inducing caution. By nightfall, the Confederates in the Orange Plank Road struggle have had it. They disengage and fall back to where they have been told Longstreet will relieve them when he arrives sometime during the night. They don’t bother to entrench. Exhausted, they fall asleep.

Meanwhile, north of the Orange Turnpike, John Sedgwick finally gets VI Corps into action.

It’s about 5 p.m. when troops of VI Corps advance against the Confederates posted behind the earthworks, which are anything but formidable. The Confederates have had little time to throw up breastworks. Desperate fighting ensues. Among the casualties is Brig. Gen. Leroy Stafford, commanding a brigade of Louisiana boys 1,200 strong. He is shot through the body, the ball lodging near his spine, and within a day he is dead. Also badly wounded is Brig. Gen. John Pegram, in charge of a brigade in Early’s division.

The Union is unable to prevail in the turnpike sector, nightfall comes, and here the Confederates work like beavers throughout the night to strengthen their position. Four hundred yards away the Yankees do the same thing—entrench. At Gettysburg you see few field fortifications. Here you see the transition that has occurred in less than a year. Soldiers now do not move any distance without entrenching. The idea to entrench comes from the bottom up, not from the top down, because the bottom people realize that if they entrench there is a better likelihood of returning home.

Thus the fighting comes to an end on May 5. Lee has offered battle, and Grant has eagerly accepted. The Confederates have had the better of the fight to this point, but Grant is not yet done. He plans to renew the attack by sending Hancock’s II Corps, reinforced by elements of V and VI Corps, to smash A. P. Hill’s front and left flank. Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps, which has finally arrived in position on Hancock’s right late that evening, will strike south into Hill’s rear.

At five o’clock on the morning of May 6, Hancock’s reinforced II Corps resumes the attack, crashing into Hill’s corps along the Orange Plank Road at dawn. Hill’s men have failed to throw up breastworks because they are under the impression that Longstreet’s corps would arrive during the night to relieve them. Staffers say the Confederate line at that time is like a Virginia worm fence. In the tangled Wilderness there is no continuity between regiments. Some face southeast, others front northeast; they have not entrenched.

Longstreet pushed his men hard on May 5. Lee opines that Longstreet will be here long before daybreak. But Longstreet realizes his men are getting tired and hungry and has called a halt. He would rather have them fresh the next morning than arrive during the night with exhausted men. So he’s not here on the morning of May 6. The Union Army is spearheaded by Meade’s best combat commander on the field. Hancock has readied a sledgehammer-like blow. He masses three brigades under Getty, and two brigades each under Birney, Mott, and Gibbon for an attack guiding on the Orange Plank Road. Wadsworth with three V Corps brigades is to attack from north to south. The Yankees assail the Confederates with more than 30,000 bluecoats. After subtracting casualties, Heth’s and Wilcox’s divisions number less than 10,000 rank and file, giving the Yankees a three to one bulge on this front.

Grant had ordered the attack to begin at 4:30 a.m. Meade tells him he can’t be ready by then, so Grant agrees to delay the attack 30 minutes. When the Federals advance, the Confederate troops yield slowly at first. Ninety minutes later they are fleeing across Widow Tapp’s farm. Lee and his staff ride out. In front of them are 16 Confederate cannon of Col. William Poague’s battalion. As soon as the infantry are out of the way, Poague’s men open fire. Lee looks south toward the Orange Plank Road and sees Brig. Gen. Sam McGowan’s South Carolina Brigade retreating. Lee calls to McGowan, “Is this splendid brigade of yours running like a flock of geese?” McGowan replies, “These men are not whipped. They only want a place to form, and they will fight as well as they ever did.”

The situation is grim. Longstreet has had his men on the road since 3 a.m.; the head of his column has reached Parker’s Store, where a side road links the Catharpin and Orange Plank Roads. As Longstreet’s men advance, one column marches on the north side of the road. It is Maj. Gen. Charles Field’s division spearheaded by the Texas Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. John Gregg. Lee does not know Gregg, who took charge of the brigade while Longstreet was in East Tennessee. On the south side of the road, stepping along parallel with them, is a brigade of South Carolinians under Col. John W. Henagan; in support of the Texans are Henry “Rock” Benning’s Georgians. As the Rebel reinforcements arrive, the Yankees are coming across the Widow Tapp’s field, seemingly irresistible as Poague’s cannon boom. Lee rides out, and the first man he encounters is General Gregg. Lee asks, “Who are these men?” and Gregg says, “The Texas Brigade.” Lee reportedly shouts, “Hurrah for Texas.” That must be bad for the morale of the Third Arkansas boys, also members of the famed brigade. Taking off his hat, Lee waves it and orders: “Go and drive out these people.”

Gregg addresses his brigade, “Men from Texas and Arkansas prepare to advance and engage the enemy. The eyes of General Lee are upon you. Forward march.” As they start to move out, who has joined them? Robert Edward Lee, mounted on Traveller, with lots of Yankees to his front. Seeing Lee the soldiers raise the cry, “Lee to the rear! Lee to the rear!” Lee continues to sit his horse, until a tall Texas sergeant comes up and grabs Traveller’s reins and leads Lee off to the rear. This will be the first of four “Lee to the rear” incidents that occur before May 13.

The Confederates then surge forward, and a titanic struggle ensues. They advance across the widow’s field, and slowly but surely drive the Federals back into the woods. Within two hours the tide of battle has turned. Longstreet’s two divisions, soon joined by Maj. Gen. Richard H. “Dick” Anderson’s unit—Hill’s other division, which has also arrived on the field—push the Union troops back to the area near today’s Hill-Ewell Drive. What had looked like an overwhelming Union success at 8 a.m. has turned into a Union repulse followed by a stalemate.

Lee and Longstreet look for ways to break the bloody stalemate. Lee’s chief engineer, Maj. Gen. Martin L. Smith, is out reconnoitering, and he discovers the unfinished railroad grade in the woods south of the Orange Plank Road. The road and railroad grade diverge as they lead eastward. He returns and briefs Lee and Lt. Col. Moxley Sorrel, Longstreet’s chief of staff. He explains that there are no Yankees posted on or near the grade. Here is an opportunity to send a column east along the grade and position the men perpendicular to the enemy’s battle line. It’s a similar situation to the one Jackson occupied and exploited vis-à-vis the XI Corps at Chancellorsville on his famed march on May 2, 1863. Only this time the foe is not XI Corps people. These are elite units of the Union Army: II Corps and one division each from V and VI Corps.

Lee meets with Longstreet and determines to attack. Sorrel guides three brigades: Brig. Gen. William “Little Billy” Mahone’s Virginians, Brig. Gen. George T. “Tige” Anderson’s Georgians, and Brig. Gen. William Wofford’s Georgians—some 3,500 soldiers—through the woods and onto the unfinished railroad. The three brigades march eastward until they are both astride and overlap Hancock’s left flank. The bluecoats are oblivious that Confederates are out there. At 11 a.m. the Rebels strike, first assailing Mott’s division. They advance along a broad front against Union troops that have no flank protection. They hit them where they are not anticipating an onslaught.

One of the first brigades the Confederates encounter, facing west with its flank toward them, is the Excelsior Brigade from New York. It is like rolling up a wet blanket as they double up the Union troops from left to right. At the same time, attacking from west to east are soldiers of Field’s division, joined by two of A. P. Hill’s divisions under Dick Anderson and Cadmus Wilcox. Hammered on the flank, assailed in front, eight Union brigades collapse. General Wadsworth tries to rally his troops north of the Plank Road, and he is shot through the back of the head. He falls from his horse, but never recovers consciousness. He is carried to Kershaw’s field hospital. Here a local farmer, Patrick McCracken, whom Wadsworth had befriended when he was military governor of the District of Columbia, calls at the field hospital. McCracken takes custody of Wadsworth’s watch and a number of his personal effects, and after he dies, sends them to the general’s family in New York State.

It’s a great moment for Lee and Longstreet. They have the Union troops on the ropes. Longstreet prepares to continue the attack. He rides from west to east along Plank Road with Micah Jenkins’s South Carolina Brigade following in a column of fours. Jenkins, 27 years old, No. 1 in his class at the Citadel, is a handsome individual. His men are dressed in new shell jackets that have a bluish cast. Out in front rides Longstreet, Jenkins, Joe Kershaw, and their staffs. On the north side of the road are about 150 men of the 12th Virginia. Most of Mahone’s Virginians, who up to now have swept all before them, are south of the Plank Road. Through the smoke they see the mounted cavalcade, riding eastward along Plank Road.

Soldiers of the 12th Virginia fire a crashing volley into the column. Longstreet is shot. The bullet slams through his right rear shoulder blade and emerges from his throat. The force of the minié ball all but lifts him out of the saddle. Jenkins is shot through the head. Two of his staff officers are dead. Amid confusion, staffers help Longstreet drop from his horse. They put him on a stretcher and everything comes to a stop on the Confederates’ part. They cover his face with his hat to conceal his identity and protect him from the sun. Rumors soon spread, Longstreet is wounded—no, he is dead. To reassure his people that he is only wounded, Longstreet raises his hat with his left hand, indicating that he lives. Cheers go up. He will not return to duty until the fourth week of October 1864.

At 4 p.m. the Confederates resume their offensive against Hancock’s new and reinforced position. From the time of Longstreet’s wounding there has been a hiatus along Hancock’s front. Union troops have entrenched behind three lines of breastworks covering the intersection of the Brock and Plank Roads and extending north and south for more than a mile. Lee now wears two hats. He is commanding Longstreet’s corps as well as the Army of Northern Virginia. He also has Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps at his disposal.

Ground fires have broken out. Why? Because it is very dry, and there are dead leaves blanketing the ground. When you fire a muzzle-loader, you first tear the paper cartridge, pour the powder down the bore, and then wad the paper. Next you place the lead projectile on the wad and use your ramrod to seat the projectile. When you fire the projectile, you have both the lead and the wadding coming out of the bore. The wadding is smoldering. If the wadding falls into dry leaves and you have wind, you can have a ground fire. A fierce fire fronting the Union breastworks starts about 300 yards south of the Plank Road. When it reaches a man who can’t move because of a broken hip or femur, he is in serious trouble. When the fire reaches his cartridge box, it cooks off the rounds and they sound like a string of firecrackers—Bang, Bang, Bang! It makes for a horrible sight.

The Confederates advance; the flames and smoke, driven by a west wind, screen them as they press ahead. Henagan’s South Carolinians and Tige Anderson’s Georgia Crackers gain the Union breastworks. The bluecoats at some point need to stand back because of the heat and have to shoot through the flames at the Rebels.

The Confederates attack; the flames are leaping up and the wind is blowing. With Micah Jenkins dead, the senior colonel, John Bratton, has taken over the brigade. Covered by the fire the Rebels rush into the Yankee works, and they’re up on top of the works. It looks like there may be a breakthrough. Fresh Union troops of Hancock’s corps, led by “Old Bricktop,” Col. Samuel Sprigg Carroll, and Col. Daniel Leasure of Burnside’s corps, seal the breach. At other points the Confederates are stopped in their tracks. Lee’s veterans vainly pound away for another hour; the fires continue to burn, and the Rebels pull back.

Checked along the Plank Road on the Federal left, General Lee rides over to the Orange Turnpike to see if there is a chance yet to garner victory out of this long and terrible day. Throughout the morning and afternoon of May 6 there is relatively little combat along and north of the Orange Turnpike. In the morning John Sedgwick is supposed to attack at the same time as Hancock, but Ewell anticipates the thrust and advances first. Within hours the fighting here ebbs.

About noon, Gen. John Brown Gordon, out reconnoitering, sees that the Union extreme right, held by Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour’s division of Sedgwick’s corps, is hanging in the air. Like Howard’s XI Corps at Chancellorsville, it’s neither anchored nor resting upon an impassible barrier. Gordon reports this to Jubal Early. Early does not believe that the Yankees can make the same mistake they did at Chancellorsville a year and four days earlier. He brings the situation to the attention of corps commander Richard Ewell.

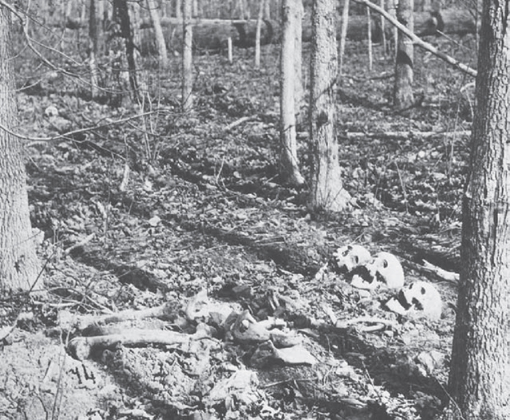

Haunting reminders of the fierce fighting that took place here, skeletons of soldiers killed during the Battle of the Wilderness are visible in this 1865 photograph.

Ewell is, as they say, dominated by petticoats, but his wife and his stepdaughters aren’t here. So that means he can be bullied by Early, a self-confident and profane individual. Early is over six feet, but he has rheumatism and both walks and stands with a stoop. He chews tobacco. His beard is turning salt and pepper and it is stained yellow around his mouth from tobacco spit. Ewell and Early pass the buck back and forth until late in the day when General Lee arrives and will finally rule in favor of an attack. When the attack is made, Gordon will commit two brigades: his own Georgians and Brig. Gen. Robert Johnston’s North Carolinians. They file out to their left to get farther north of the Union lines and well beyond Seymour’s right flank. They deploy, facing south; Johnston is on the left and Col. Clement A. Evans with Gordon’s Georgians is on the right, and they sweep toward the Union flank.

Seymour’s people hear them coming. A quarter of a mile away, they hear high-pitched Rebel Yells. Soon they see their comrades running toward them, pursued by Confederates. Had the Yankees refused their line, they probably could have checked the attack. Instead the butternuts scoop up hundreds of prisoners and two brigadier generals—Truman Seymour and Alexander Shaler.

The Confederate attack first slows and then stalls. The Yanks stabilize their line; it’s growing dark. Supporting Confederates on Gordon’s right make no headway. Gordon lacks men to exploit his gains. Meanwhile, the Union calls up reserves and forms a new front at a right angle to oppose Gordon.

There is panic at Union headquarters. It’s rumored that Sedgwick has been killed or captured. Confederate success is exaggerated. There are wild rumors: the Confederates have reached the Germanna Plank Road, cutting communications with Germanna Ford. When Grant hears this he caustically remarks, “I am heartily tired of hearing about what General Lee is going to do. Some of you always seem to think he is going to turn a double somersault and land in our rear and both of our flanks at the same time. Let’s start talking about what we can do ourselves and not what General Lee can do.” Grant asserts himself again to show he is going to get more involved in providing overall guidance for the Army of the Potomac. In Grant’s staff officers’ minds, Meade is beginning to lose operational control of his army.

On the morning of May 7, VI Corps reestablishes its line on the right by pulling back and entrenching. The Confederates occupy the abandoned Union fortifications and reface them fronting southeast and paralleling Sedgwick’s. It’s been a bloody battle. Union casualties for the two-day battle number more than 17,600, and for the Confederates about 11,000. Grant now shows his will. If he had been a General Hooker or General Burnside or General Meade he would have gone back across the Rapidan on the night of the sixth. Instead he will head to Spotsylvania Court House to continue the fight. When the Union troops, after all those losses, find out they’re not going back across the Rapidan, there is tremendous cheering that evening. All the Confederates, except General Lee, think that they’ve won the battle and that the Yankees are going back across the river. Lee is the only one in authority in the Confederate Army who is convinced Grant will resume the march through the Wilderness. Napoleon Bonaparte said that a successful general has to look into the enemy’s eyes and know what he is thinking. Lee has looked into Grant’s eyes and knows what he is going to do.