MAY 20, 1864–JULY 30, 1864

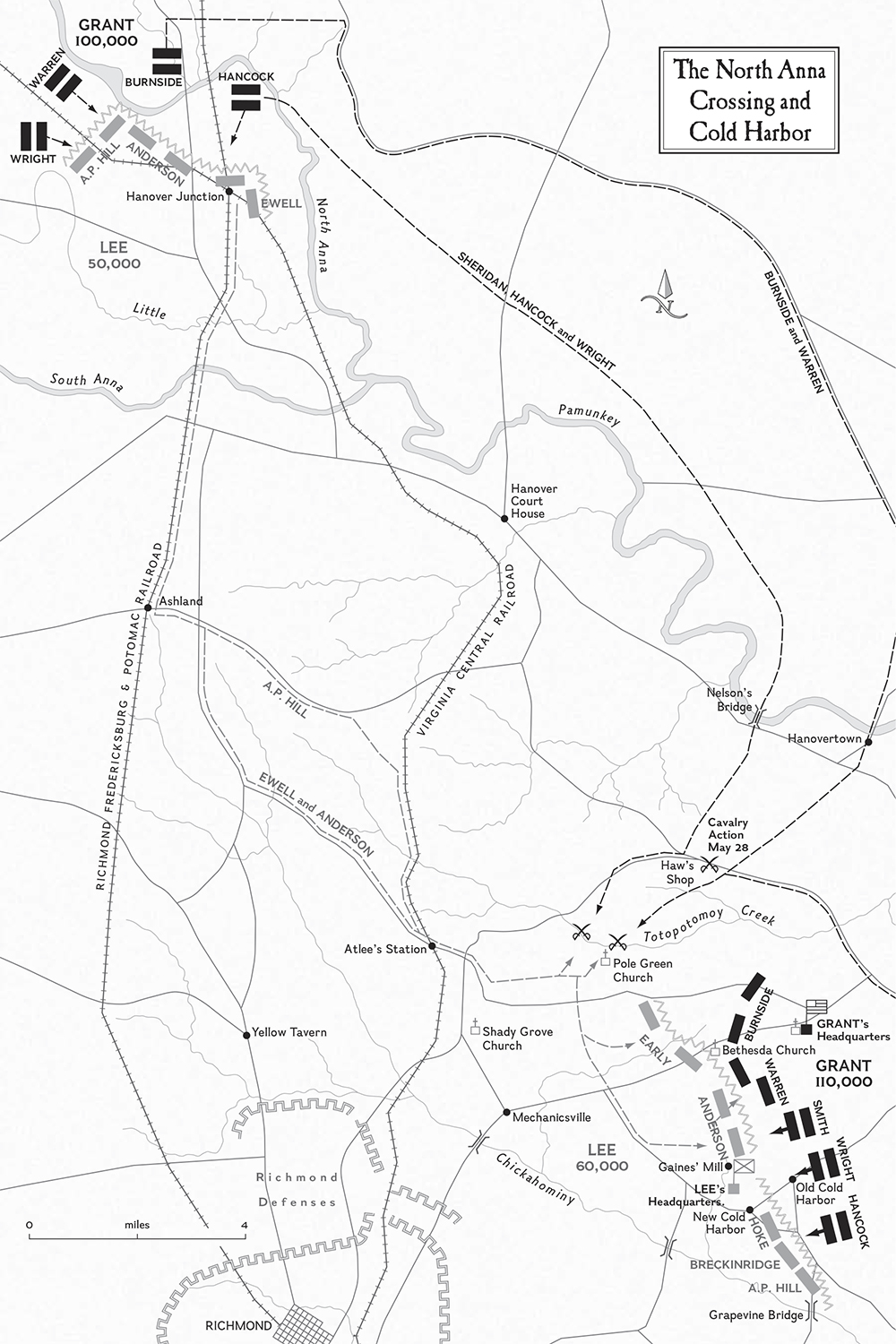

Stalled at Spotsylvania, Ulysses S. Grant decided that he would continue to press southward around Lee’s right flank. The Confederate capital at Richmond was only 50 miles away. Lee had no choice but to follow.

On the night of May 20, Grant disengages and commences another swing around Lee’s right. General Hancock takes the lead with his once-powerful corps, which has been badly weakened in the fighting of the previous three weeks. They move out toward Guinea Station, where Stonewall Jackson died a year earlier. Army of the Potomac commander Meade advances Hancock as bait, hoping that Lee would move out of his formidable Spotsylvania works and attack him. If Lee does not choose to come out and assail Hancock, Lee will be flanked out of his position, and compelled to fall back.

Lee does not go for the bait. He holds his position until May 21, when he learns from his cavalry that Federals have mauled one of his infantry brigades at Milford. The Rebels throw forward skirmishers, and find that the Union Spotsylvania lines east of the Ni have been weakened. There is fighting along the sector of the Union works held by Wright’s VI Corps, which will be the last of Meade’s army to move out of Spotsylvania County and head south. Lee realizes what Grant is doing and puts his army in motion for the North Anna River. The Confederates win the race to the North Anna and arrive there on the morning of May 22 and take position with Ewell’s corps on the right and Richard Anderson’s corps, when it comes up, in the center. The last corps to arrive is A. P. Hill’s, and it’s posted on the left. Coming from the Shenandoah Valley is Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s division, which had defeated Gen. Franz Sigel at New Market on May 15. Breckinridge reports directly to Lee: He is held in reserve. Also arrived is George E. Pickett’s division from Richmond, where his people fighting under Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard have helped best Butler’s Army of the James at Drewry’s Bluff on May 15–16.

Grant moves up rapidly on May 23. On the north side of the river the Confederates leave a small force to hold Henagan’s Redoubt. Hancock arrives first, and one of his division commanders, David Birney, throws two brigades against the redoubt, overwhelms it, and next morning crosses the North Anna. Meanwhile, upstream some five or six miles, at Jericho Mill, Warren’s corps has reached a point where it finds the ford unguarded and crosses there. A. P. Hill moves forward to attack the Union forces, using only Wilcox’s division. They throw back a reconstituted Iron Brigade, and the Yankees give ground. However, Hill neglects to support the attack, and Warren calls up reinforcements and Wilcox disengages. Lee will chide Hill, saying, “Why did you not do what Jackson would have done—thrown your whole force upon these people and driven them back?”

On the morning of May 24 Hancock’s corps crosses the North Anna and begins moving immediately to the high ground to the south. The Confederates hold Ox Ford with “Little Billy” Mahone’s division of Hill’s corps. Entrenched on Mahone’s left are Hill’s other two divisions, the left of Heth, anchored on Little River. Anderson’s corps on Mahone’s right fronts the North Anna, while Ewell’s corps and Breckinridge’s division guard Lee’s right, covering the vital Hanover Junction railroad crossover. The Confederate line forms a V with its strongest point at Ox Ford, where Hill on the left and Ewell on the right can promptly reinforce each other as the situation warrants.

Soldiers of Company B, 170th New York Volunteers, play cards, read, and smoke in this undated photograph. They would suffer heavy causalities in fighting at Spotsylvania and the North Anna.

Lee succeeds in placing Grant in an embarrassing situation. To reinforce his left with his right or his right with his left, he has to bypass Burnside’s troops at Ox Ford and cross the river a second time. In describing Grant’s dilemma, Confederate Brig. Gen. Evander M. Law wrote, he “had cut his army in two by running it upon the point of a wedge.”

But Lee has leadership problems. Ewell has been plagued by declining health, lack of mobility because of his leg amputation, and perceived loss of judgment at critical times during the Spotsylvania fighting, particularly at Doles’s salient on May 10 and again at Harris Farm nine days later. At the latter he got more than 900 soldiers killed or wounded in an ill-advised reconnaissance in force. Hill, beginning at Gettysburg, then at Bristoe Station, and again at Jericho Mill, has proven to be an ineffective corps commander. Anderson is new to corps leadership, and Lee is ill.

Lee seeks to run his army from an ambulance and his tent, but he is unable to get anything to jell and take advantage of Grant’s gross tactical error. Nothing happens and Lee declares, “We must strike them a blow—we must never let them pass us again—we must strike them a blow.” Even so, it would be difficult to drive Hancock’s corps, already throwing up breastworks, back into the North Anna. In addition to the day’s skirmishing along Hancock’s front, a blunder at Ox Ford by Burnside brigade leader James H. Ledlie costs his command dearly. A heavy drinker, “full of Dutch courage,” Ledlie sends his troops to be slaughtered against formidable works defended by Mahone’s people. As too often happens, Ledlie will soon be promoted to lead a division, where we will hear more about him on July 30, at Petersburg’s Crater.

On the afternoon of May 24, Sheridan’s cavalry corps rejoins the army on the North Anna from the road that had taken it to Yellow Tavern and beyond. With the return of Sheridan, and checked on the North Anna, Grant by the 26th is ready to move on. He again, as he had on the march to Spotsylvania and again to the North Anna, sends Meade’s army on a wide jug-handle swing to get around Lee’s right flank. He transfers his supply base from Port Royal on the Rappahannock to the head of steamboat navigation at White House Landing on the Pamunkey, back where McClellan had been in his Peninsula campaign two years before. “Harry” Wilson’s cavalry will try to keep Lee in his position behind the North Anna as long as possible and then follows along behind the army as it heads southeast. Lee on May 27 throws out patrols and finds the Yankees gone. Lee marches across the chord, so he travels a shorter distance. He moves out and masses his army in the Ashland area, where he will be positioned to intercept Grant wherever he crosses the Pamunkey River and strikes southwest toward Richmond. Ewell has for some time been in poor health, and Lee urges him to take a long sick leave, which Ewell is reluctant to do, but Lee insists. He names Jubal Early to command the II Corps. Early had had experience earlier leading Ewell’s corps. He had led it in the Mine Run campaign in the fall of 1863 when Ewell became too sick to command, and he had led III Corps during most of the fighting at Spotsylvania, when, as so frequently happens, Hill reports himself sick.

On May 31, Federal cavalry seized the crossroad at Old Cold Harbor, turning back an attack by Confederate infantry. Confederate reinforcements arrived and dug in. Late on June 1, Federal infantry reached Cold Harbor and assaulted the Confederate works. By the following day both armies had arrived, facing each other on a seven-mile front between Bethesda Church and the Chickahominy River. At dawn on June 3, a massive Federal assault was repulsed with heavy casualties. On the night of June 12 Grant abandoned his entrenchments and shifted his forces by the left flank toward the James River.

Escaping from Lee’s trap at the North Anna, Grant swings south once more across Lee’s right flank. For several days the two armies race southward, clashing in a series of sharp fights at Haw’s Shop (May 28), Totopotomoy Creek (May 29–June 1), Bethesda Church (May 30), and other places. On the afternoon of May 31, Sheridan’s cavalry in a bitter fight bests Fitz Lee’s horse soldiers and takes possession of a crossroad at a place called Old Cold Harbor. Satisfied that Lee’s army is on its last legs, Grant decides to deliver one more blow. To help, he has ordered the transfer of William F. ‘Baldy” Smith’s XVIII Corps from Butler’s Army of the James.

On the morning of June 1, an effort by Lee’s infantry to recover Old Cold Harbor misfires. A late afternoon attack by Smith’s corps and Horatio G. Wright’s VI Corps ruptures the Confederate line held by Kershaw’s division of Anderson’s corps and Clingman’s Tarheels of Robert Hoke’s division north of the Cold Harbor Road and west of today’s national cemetery. Rebel reinforcements are called up; Field’s people rally, and seal the breach. When nightfall ends the day’s fighting, the Federals count more than 2,100 casualties, but they have captured more than 750 prisoners. These gains encourage Grant and Meade. Hancock’s corps, posted along the Totopotomoy, is called upon to make a night march and take post on the left of Wright’s VI Corps astride the headwaters of Boatswain Swamp, paralleling the Dispatch Station Road. Hancock’s men, because of poor maps and confused orders, are exhausted by their march, and Grant twice postpones his June 2 attack order.

As Grant’s aide Horace Porter wanders around that night, he will tell us in his memoirs, he notices a number of men taking off their coats, and he wonders if they are repairing their clothes or searching for and crushing lice. He looks closely and can see that a number of them are pinning their names onto their clothes. The soldiers realize what is coming even if Grant and Meade do not. There were no GI dog tags in the Civil War, although you could buy them from sutlers.

Commissary sergeants issue two days’ rations to the troops, and they draw their full units of fire. Horatio Wright deploys the three divisions of his VI Corps with Russell on the left, Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts in the center, and Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Neill on the right. Skirmishers will be out in front, and again, like it was on the first, their axis of advance will be the Mechanicsville Road that leads west to New Cold Harbor. On his right is “Baldy” Smith’s corps. Smith and Wright are both engineers by training, and Smith asks Wright, “what are you going to do?” Wright says, “my orders are to pitch into the enemy and not to pay any attention to what is going on to my right or to my left.” Smith is incensed by Wright’s words, and he explodes to his staff that the attack is “simply an order to slaughter my best troops.” He examines the ground in front of him. The ground is quite level, but there are some elevations that have enabled Confederate engineers to lay out an intricate system of works, fronting which are few areas not covered by fire. Smith noticed that a watercourse draining west into Powhite Creek would give his men some cover from enemy fire; he plans to use it as he advances.

The Confederates take care of Wright quickly. Wright’s men attack straight ahead. Within a very short time, VI Corps will grind to a stop with relatively light casualties compared to the other two attacking corps. Wright reports his men pinned down, no further gains possible. Some of the Confederates are sorry for the Yanks. Others are not.

On the left, Hancock attacks on a two-division front—Barlow on the right, Gibbon on the left. He has not reconnoitered. And as Barlow’s people advance Col. John R. Brooke leads his men forward across a level area fronted by what has been a swamp. The Confederates pulled their pickets out of there because it had been raining most of the night. The Yanks storm forward, penetrate the Rebel works, and capture three cannon, one stand of colors, and 200 men of Edgar’s 26th Virginia battalion. Brooke is shot down. Off to his left Nelson Miles’s men likewise reach the Rebel works. To the counterattack comes Joe Finegan’s Florida Brigade up from the reserve. All good Irishmen will be delighted with Finegan and his Floridians. With their leadership shattered, crowding up on Brooke’s and Miles’s brigades is Richard Byrnes at the head of the Irish Brigade. He’s killed. Barlow’s Yankees, having suffered a loss of more than a thousand men, fall back several hundred yards. They dig in with their mess gear and anything else they can lay their hands on.

Gibbon’s division, as it presses ahead on Barlow’s right, finds its front divided by a hollow formed by Boatswain Creek, which deepens and widens as it nears the Confederate earthworks. On the right, Brig. Gen. Robert Tyler, north of Boatswain Creek, is shot down and wounded as he leads his men forward. Pressing forward behind them is Boyd McKeen’s brigade; McKeen will go down, and Frank Haskell will take over the brigade and seek to lead it onward, only to be mortally wounded. The 164th New York Zouaves storms forward south of Boatswain Creek, Col. Martin T. McMahon leading them. He plants the colors on the Rebel works, where he dies. Gibbon pulls back and, like Barlow, reports more than a thousand casualties.

Baldy Smith commits two of his three divisions—William T. H. “Bully” Brooks’s and John H. Matindale’s—to the onslaught. They advance on a narrow front by columns of divisions separated by Middle Ravine, which, like Boatswain Creek, drains to the west. As they surge forward, first Brooks’s people on the left and then Martindale’s on the right find themselves pocketed by “Tige” Anderson’s Georgians on their left and Evander Law’s Alabamians on their right. The latter recalled his men’s morale was sky high—laughing and talking as they “fired” at the oncoming bluecoats. He was taken aback by what he saw: United States and regimental colors being advanced, and then several puffs of dust as minié balls struck chests, and the foe fell like a row of dominos. Law, a veteran of the killing grounds of Second Manassas and Fredericksburg, recalled that this “was not war, it was murder.”

Smith’s attack stalls and, like Wright and Hancock, he reports no gains and heavy losses. Grant encourages Meade to continue the attack: Meade tells the corps commanders to continue to push ahead without reference to the units to their left and right. If they do so and the corps to their left and right don’t gain ground, they will find themselves in a salient and get shot to pieces. They send back for further orders. The orders are to continue the attack. Capt. Thomas Barker, leading the 12th New Hampshire, is angered by such foolishness and shouts, “I will not take my men into another charge if it was an order from Jesus Christ.” Men lie on the ground and fire into the air. Although the orders are to continue the advance, they’re not going to. They will hold where they are. By noon orders come down from Grant through Meade to cease the attack. “Dig in and hold the ground.”

Grant and Meade do not realize the full impact of what has happened. Grant telegraphs to General Halleck that afternoon and reports the attack. He notes that his men have gained positions close in to the Rebel lines, and that losses in the Confederate and Union armies have been modest. It hasn’t struck him what has happened, nor does Meade realize the full impact of what it implies when soldiers go to ground and refuse to charge a second and third time when ordered. Meanwhile, Union soldiers entrench along the ridge line to hold the ground they have gained. The first trenches are farthest to the east. Between June 3 to June 12, they’ll inch their trenches ever closer to the Confederate lines, while Grant ponders his next step.

Meanwhile, fighting breaks out on the Confederate left along the Shady Grove Road when soldiers of Burnside’s IX Corps, supported by Warren’s, assail Early’s corps. The Confederates, again fighting behind earthworks, hold their own—the Federals in this fighting lose another 1,200 men. Added to the 4,500 cut down in the Old Cold Harbor sector, Union casualties for the day number 6,000.

Lee at first does not realize how disastrous for the Federals the repulse has been. At the end of the day he reports that they again turned back the Federals, and with the blessing of God they’ve won a success. On the field, in the Middle Ravine, along either side of the Cold Harbor Road, and north and south of Boatswain Creek, dead and wounded Union soldiers lie in great numbers. Many Confederates do not realize a major attack had been made. Later on in the afternoon there is some heavy firing as each side advances skirmish lines. Grant orders a systematic approach. Wounded Yankees, the ones closest to the lines, are taken back to aid stations. You can hear in the evening the pitiful wails of “water, water” rising. Out in front, in no-man’sland, more and more of the wounded die—the bodies turn black and bloat. Finally, on June 7, when Grant finally makes a tacit acknowledgment of defeat, there is a brief truce, which enables the Federals to come out, recover and bury their dead, and succor any wounded still alive out there.

The Battle of Cold Harbor is a disaster for Grant. Although reports that some 7,000 men fell in less than 30 minutes are highly exaggerated, the truth—that perhaps 4,500 men fell in a few hours—is bad enough. Other generals launched costlier assaults at Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, and Franklin, to name but a few, but it would be Cold Harbor that would forever give Grant the reputation of being a butcher.

Yet the setback at Cold Harbor proved only temporary. Grant immediately contemplated a new operation. This time he eyed Petersburg, Virginia, as his target. Due south of Richmond, on the Appomattox River, Petersburg was a key strategic point, for if the Union captures it, Richmond would be virtually cut off from the rest of the Confederacy. To get there, however, would require skill and daring, for along the way Grant would have to cross the James River, all the while making sure that Lee did not seize an opportunity to deal the Yankees a serious and perhaps decisive blow while they are astride the river.

Petersburg was Virginia’s second city in 1860, with a population of 18,000. Petersburg is known as the “Cockade City” because of its support for the War of 1812. It is important as a tobacco processing and cotton milling center and county seat. Because of its railroads, it is the gateway to Richmond from the South. Small deep-draft steamboats cannot reach Petersburg, which is located at the fall line of the Appomattox River. Coming into Petersburg are several railroads. From the east at City Point is the City Point Railroad. Coming into Petersburg from the south and a little to the east is the Petersburg & Norfolk Railroad, continuing on to Norfolk. Coming into Petersburg from the south is a very important railroad, the Weldon Railroad. The Weldon Railroad connects Petersburg with the blockade-running center at Wilmington, North Carolina, and with the North Carolina railroad system. Coming into Petersburg from the west, on the south side of the Appomattox River, is the South Side Railroad, which leads from Petersburg to Lynchburg, where it ties into the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad and the Orange & Alexandria. About 50 miles west of Petersburg is Burke’s Station, modern-day Burkesville. At Burke’s Station, the South Side Railroad crosses the Richmond & Danville Railroad coming out of Richmond. The final railroad leading north out of Petersburg is the Petersburg & Richmond.

Petersburg was vulnerable in the summer of 1862, when General McClellan thought of attacking it in the aftermath of the Seven Days’ Battle and his retreat to Harrison’s Landing. Since then there have been changes. It is no longer an unfortified rail center. The Confederates have laid out what became known as the “Dimmock Line,” and it guards all of the Petersburg approaches from south of the river. The Dimmock Line began on the Appomattox River two miles downstream from Petersburg at Battery No. 1. It then circled Petersburg, staying at a distance of about 2.5 miles from the important rail center. It anchored on the right on the Appomattox River two miles upstream from Petersburg. It consisted of 55 batteries with a connecting line of earthworks. This is what is going to confront Grant when he crosses the James River and moves west. When the first Federals cross the river on the night of June 14–15, there are less than 3,100 Confederate troops to occupy the ten-mile perimeter.

Following the bloody June 3 attack at Cold Harbor, Grant sends Sheridan with two cavalry divisions on a raid into piedmont Virginia. Sheridan is to wreak havoc on the Virginia Central Railroad, go on to Charlottesville, and establish contact with Maj. Gen. David “Black Dave” Hunter’s army, which has advanced far up the Shenandoah Valley. Learning of the departure of Sheridan, General Lee bites the bullet. He selects Wade Hampton to succeed Jeb Stuart as his chief of cavalry. Hampton is sent in pursuit of Phil Sheridan; he will fight and best him at the Battle of Trevilian Station, with heavy losses on both sides. Sheridan returns without completing his mission. Hunter has been raising hell with the Confederates in the Shenandoah Valley. He defeats the Confederate defenders of the valley at Piedmont on June 5 and occupies Staunton the next day. Lee responds by sending General Breckinridge and his small division back to the valley. But Hunter, now reinforced by a Union column from West Virginia, takes Lexington on June 11 and torches the Virginia Military Institute. Lee is forced to detach Jubal Early’s corps to put a stop to Hunter’s rampage. That leaves Lee on June 13 with just two corps, commanded by Richard Anderson and A. P. Hill, plus Robert Hoke’s division on loan from Beauregard’s command.

On June 12 Grant breaks contact with Lee and starts for the James River, the first obstacle on his way to capture Petersburg, the back door to Richmond. He assigns a major role in the operation to Baldy Smith. Grant had thought highly of Smith since the autumn of 1863, when he played a major role in establishing the “Cracker Line,” the initial step on the road to Union victory at Chattanooga. He had indicated to Smith that the latter would replace Meade. After meeting Meade, however, Grant changed his mind. Instead, he decided to assign Smith to duty under Benjamin Butler in the Army of the James. When Meade’s Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River, Butler moved the Army of the James, consisting of two army corps, by water up the James River and occupied Bermuda Hundred. Butler sought and failed to break into Richmond from the south. He then pulled back into Bermuda Hundred, where he was bottled up by Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard’s smaller army.

Grant’s plan evolves as follows: Meade gradually pulls back his right wing and it entrenches. He then extends his left wing out to the Chickahominy River. Under cover of darkness on the night of June 12, Smith’s corps departs the Cold Harbor line and marches back to White House Landing and boards transports. By nightfall on the 14th, having gone down the Pamunkey and York Rivers, by Hampton Roads, and up the James River, Smith’s people land at Bermuda Hundred. Meanwhile, Warren’s V Corps, on the extreme right of the Army of the Potomac, having gone into reserve, crosses the Chickahominy River at Bottoms Bridge and advances on Richmond via the Long Bridge Road to Glendale. Warren is accompanied by Harry Wilson’s cavalry division.

It’s all ruse—and Lee falls for it. He redeploys his army south of the Chickahominy and takes position south of White Oak Swamp and north of Malvern Hill fronting east. Here Lee’s people skirmish with Warren and Wilson. Lee is certain Grant is going to attack through that area. Meanwhile, the remainder of the Union Army, composed of Burnside’s IX Corps, Wright’s VI Corps, and Hancock’s II Corps, disappears from the Cold Harbor battlefield and crosses the Chickahominy River downstream from Bottoms Bridge. The army trains cross the river farther downstream near Williamsburg at Jones Bridge. General Hancock’s II Corps is a ghost of its former self. Since crossing the Rapidan in early May, it has suffered 16,000 casualties. The casualties have been replaced as to numbers, but missing are the “old breed,” so the quality is down. Many of the newcomers are recruits, bounty jumpers, conscripts, and the “heavies,” people that have been manning the heavy guns in the Washington fortifications. Hancock himself is not his old self. The wound he received in the groin at Gettysburg is bothering him. A Confederate minié ball had crashed into the pommel of his saddle and had driven through seven inches of flesh and lodged against his tailbone. The bullet had been removed, but there is shattered bone in the wound, which develops into osteomyelitis. There are splinters of broken saddle framing in his wound as well. In those days you rode a horse. And, as the campaign continues, he is going to get very sore, and by June 17 his wound is going to break open and start draining puss and blood.

By midday of June 14, Beauregard knows he is in serious trouble. Where are Beauregard’s men? He has sent Robert Hoke’s division, his biggest, to Cold Harbor with General Lee. Bushrod R. Johnson is holding the Bermuda Hundred line with 4,000 men opposing the Army of the James’s X Corps. General Butler is there still, neatly corked in a bottle. Holding the Petersburg perimeter, ten miles in extent, are the 2,400 men of Henry Wise, ex-governor of Virginia, who has no use for those damn West Pointers. An ascerbic personality, he is General Meade’s brother-in-law. Beauregard also has James Dearing’s 800 cavalrymen and the militia.

Grant is in an excellent position to score a knockout blow to the Petersburg Confederates. Beauregard is at Petersburg with about 3,200 men. Johnson is holding the Howlett line. General Early is heading toward the Shenandoah Valley as fast as he can march. Wade Hampton, with his and Fitz Lee’s divisions of cavalry, is en route from Trevilian Station, having checkmated Sheridan. Rooney Lee’s cavalry and Hill’s and Anderson’s infantry are north of the James River, protecting Richmond from Warren’s infantry and Wilson’s cavalry, which, unknown to “Marse” Robert, no longer constitutes a threat to the Confederate capital.

Federal engineers constructed a pontoon bridge across the James River in a matter of hours. The bridge stretched close to half a mile across the river, and withstood the river’s strong currents.

As darkness falls on June 14, Hancock’s columns arrive at Wilcox’s Landing; throughout the night, they’re ferried across the river and land on the south side of the James. There is a snafu. The problem is an order drafted at army headquarters. The staffers order Hancock across the river with three divisions, about 20,000 men. Hancock is to provide rations for the troops before moving out. It will be 10:30 a.m. on the 15th before the men draw their three days’ rations. They then march toward Petersburg. The map Hancock is using has two streams confused. They are to go to a point near Petersburg on Harrison’s Bed (bed is a name used locally for streams or runs), where the Confederates have an earthwork. There are two Harrison creeks. The one that shows on the Union headquarters map is at Baylor’s Farm. The one that Hancock’s men are to march to is behind the Dimmock Line. Thus, Hancock has bad information, and he is not told that there is any need to hurry.

Windmill Point, several miles downstream below Charles City Court House, is the narrowest place on the James between Hampton Roads and City Point. Here the engineers construct what is then considered a miracle—a long pontoon bridge across a tidal river. They have their bridging equipment down at Hampton Roads. They come up the river on June 14 and, at dusk, they unload 101 pontoons and, during the next eight hours, they lay the bridge across the river—2,200 feet, or almost half a mile in length. There is a strong tidal ebb and surge, so they have to secure scows at various points to anchor the lines that hold the bridge in position. Also, they cannot close the river to traffic because of the passage of gunboats and transports. The center section of the bridge has to swing. It is quite an engineering task to build this bridge, equal in complexity to bridging the Rhine in March 1945.

Grant meets with Butler and Smith at Bermuda Hundred. He will send Smith with two—Martindale’s and Brooks’s—of the three divisions that had accompanied him to and from Cold Harbor across the Appomattox River. He will have attached to him a division of blacks that has been landed at City Point since June 5. They are led by Massachusetts-born Brig. Gen. Edward W. Hincks. They will be accompanied by August V. Kautz’s cavalry division.

Smith’s two infantry divisions cross over from Bermuda Hundred on a pontoon bridge at Pocahontas. They are expected to be in position to carry the Confederate defenses by 10 a.m. The first engagement takes place at Baylor’s Farm between Kautz’s cavalry and 600 Rebel horse soldiers supported by three cannon of the Petersburg Artillery. The Confederates will check Kautz’s cavalry, and then the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry appears. They charge the Rebels, and get favorable publicity because the periodicals feature sketches of the blacks bringing in a captured cannon. It is a shot in the arm for black recruiting, but Kautz has squandered valuable time.

When Smith’s two white divisions approach Petersburg, they are on a broad front: Martindale is on the right; moving along the railroad is Brooks. On Brooks’s left will be Hincks’s black division, and on Hincks’s left is Kautz’s cavalry. The Federals by early afternoon have positioned 15,000 soldiers fronting the Rebel works, from Battery No. 1 on the north to Battery No. 20 on the south. Hancock is en route and closing with another 20,000 men. Opposing them, Beauregard has Wise’s 2,200 men to defend Petersburg with another 3,200 confronting Butler at Bermuda Hundred. Lee is north of the James with more than 40,000 men. The only Union troops in front of Lee from June 13 to the 14th are Warren’s V Corps and Wilson’s cavalry. Lee made several errors during the war, and this is one of them. Lee’s admirers do not like to spend much time on this period in his military career.

Smith and Kautz, however, dawdle. It is 7 p.m. before Smith, now overly cautious because of his experience in attacking Confederate breastworks at Cold Harbor on June 1 and 3, sends a reinforced skirmish line drawn from Brooks’s division forward. The Yanks encounter sharp small-arms fire but carry the salient defended by Battery Nos. 4–6, capturing several hundred prisoners and four cannon. Hincks’s division attacks at the same time that Smith is attacking Battery No. 5. Hincks’s black regiments crack the Confederate line, capturing Battery Nos. 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11. Each of these batteries emplaced one to two guns. The Union forces have now breached the Confederate lines over the distance of a one-mile front.

It is a moonlit night. Smith hears locomotives chuffing. Beauregard has requested the return of Hoke’s division, loaned to Lee. Hoke had arrived with his men at Cold Harbor on May 30 in the nick of time and had remained north of the James with Lee until 5 p.m. on June 14. Hoke’s division marches to Drewry’s Bluff, crosses the James River pontoon bridge, and entrains. The first cars cross the Appomattox into Petersburg about 7:30 p.m., carrying Johnson Hagood’s South Carolinians. They are followed by other troops of Hoke’s. The Federals detect this movement from signal towers.

Smith is dismayed by this news. He goes to Hancock, who is finally on the field. Smith asks Hancock to relieve his Army of the James people. It is 11 p.m. before the II Corps troops complete the relief of Smith’s men. While Hancock and Smith posture and procrastinate, more of Hoke’s units reach Petersburg by rail and are quick-timed out to the danger point.

By morning on June 16, the Confederate forces available to Beauregard for the defense of Petersburg have been increased from 3,200 men (not counting the home guard) to more than 10,000 men. The Union has wasted many hours. Hancock’s men are ordered to attack, but it is almost noon before his corps launches its first attack, led by David Birney’s division. Col. Thomas W. Egan’s brigade spearheads the attack against the Confederate lines and captures Battery No. 12. Egan is badly wounded. Later in the day, the division attacks again. You do not want to command the Irish Brigade. This is a brigade consisting of the 63rd, 69th, and 88th New York and the 28th Massachusetts. At Cold Harbor on June 3, Col. Richard Byrnes had been killed leading the brigade. Today, Col. Patrick Kelly will be killed. In the afternoon attack the bluecoats storm Battery Nos. 13–16. As the crisis deepens, General Beauregard messages both Lee and the Confederate War Department that he must pull Bushrod Johnson out of the Howlett line, because of the continued Union buildup in front of Petersburg with the arrival of Burnside’s IX Corps from Windmill Point. With Johnson’s departure for Petersburg, Beauregard warns, the cork will be out of the bottle and Butler will be free to sweep west and, again as he had in mid-May, sever the railroad and pike linking Petersburg and Richmond.

By nightfall on June 16, Beauregard, with the arrival of Johnson, has more than 14,000 men in Petersburg. The Federals’ increases during the day boost their strength to 55,000. Although they move slowly, on the evening of the 16th Butler’s troops occupy part of the trenches Johnson abandoned on the Howlett line. The timely arrival of Pickett’s division, rushed to the danger point by Lee, followed by a savage counterattack, drives Butler’s men out of their Howlett line toehold.

The Federals have missed a once-in-the-war opportunity, which condemns thousands of men on both sides to death, disabling wounds, and a long, hard winter before Petersburg eventually falls. The Yanks have Petersburg within their grasp on the evening of June 15 and again the next night, but each time irresponsible leadership lets it slip away.

Smith is not the only Union commander to forfeit an opportunity on June 15 and 16. To his left one of his divisions, composed of black regiments under Edward Hincks, scores some early successes.

The vanguard of Burnside’s IX Corps by 10 a.m. on June 16 is posted on the left of Hancock. At dawn the next day, Brig. Gen. Robert Potter’s division storms forward. Depending on the bayonet, the Yanks take the Confederates of Johnson’s division by surprise, and capture more than 600, many of them asleep. In addition to carrying the Rebel works at the Shind House, Potter’s people also seize four cannon and five stands of colors. Attacks later in the day by Burnside’s two other white divisions, supported by II Corps troops on their right, yield minor gains before being checked by Brig. Gen. Archibald Gracie’s Tennessee Brigade, and again success has eluded Grant and his generals.

Beauregard wonders when and if Lee will cross the James and rush south to aid in the defense of Petersburg. He instructs his chief engineer, Col. David B. Harris, to lay out a new defense line covering the eastern approaches to the Cockade City. The Confederates have lost the defenses of the Dimmock Line from Battery No. 4 to Battery No. 16. His two divisions—Hoke’s and Johnson’s—have fallen back and entrenched on the west side of Harrison’s Bed. Harris selects a new defense line on commanding ground a mile east of Petersburg. His engineers walk and stake out positions where the troops are to dig in. Under cover of darkness on June 17–18, the Confederates abandon their temporary line behind Harrison’s Bed, and fall back to the new line anchored on Battery Nos. 1, 2, and 3 and extending southward to Colquitt’s Salient and beyond to Rives’s Salient. This new line is fronted by Taylor’s Branch from Rives’s Salient to the Hare House. The Confederates are prepared for an all-out Federal attack slated for the morning of June 18.

The June 18 fighting is often overlooked. If you were a soldier in the Army of the Potomac or the Army of the James, you would rather be at Cold Harbor from May 31 through June 4 than at Petersburg between June 15 and 18, because you would have a better chance of getting killed, wounded, or captured at the latter. The Petersburg assaults do not get the same press and publicity as those at Cold Harbor.

By morning on June 18 Wright’s VI Corps has arrived from Windmill Point, taking position on the right of the Federal line. Hancock is incapacitated by his Gettysburg wound, and turns command of the II Corps over to General Birney. On Hancock’s left is Burnside; on Burnside’s left is Warren. Almost 67,000 Union troops close on the new Confederate defense line guarding Petersburg. They come upon the old Confederate defense line where they find abandoned rifle pits, huts, stragglers, and fresh graves. They press onward to encounter stiff resistance from the Rebels, who by morning had been reinforced by General Lee with two divisions of his Army of Northern Virginia veterans, in their new defensive positions. The fighting is more bitter, if possible, than it was at Cold Harbor. Between June 15 and 18, the Federals will lose more than 11,000 troops killed, wounded, and missing. When the II Corps is ordered to advance later in the afternoon on the 18th, they refuse to go forward. Instead, they lie upon the ground and fire their weapons into the air. They have reached a point—they are not going to participate in any more frontal assaults. This is a very critical time for Meade’s Army of the Potomac, which has lost more than 65,000 men since crossing the Rapidan River in early May. Their opponents have lost more than 40,000 men.

June 18, 1864, is a terrible day for the Union Army. Several examples will suffice. The First Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment had been in the army since late summer 1862, manning artillery in the Washington Defenses. They came to the front when Grant called upon the heavy artillery regiments for combat duty in mid-May. Seeing their first serious combat, they go forward elbow to elbow in line of battle, some 900 strong, to face death and destruction at the hands of the well-entrenched Rebel defenders of Colquitt’s Salient. Six hundred thirty-two Maine men are killed, wounded, or missing in action in minutes. It’s the heaviest loss for any regiment during the Civil War. Other regiments will lose greater percentages, but no other unit will lose that many men in a day’s action during the war.

Some of the vast network of earthworks erected by defending Confederate soldiers at Petersburg, Virginia. The siege of Petersburg would last until the closing days of the war.

Joshua Chamberlain, now leading a V Corps brigade against Rives’s Salient, is gravely wounded when cut down by a Rebel minié ball that strikes him in the pelvis, twice penetrating his bladder. He will recover from this life-threatening wound and be a major player at the Appomattox Court House drama.

The Confederates, posted behind breastworks, suffer far fewer casualties in the day’s fighting. The Army of the Potomac has reached, momentarily, the end of the line. Grant realizes that he has a serious morale problem among the troops. The esprit of the army’s frontline soldiers is at an all-time low. Grant decides it is senseless to continue to assault enemy earthworks and breaks off the attacks. He will not again send Meade’s people against earthworks until the Battle of the Crater, which is an aberration. Instead, he moves farther west into open country, seeking to cut the remaining Confederate rail lines entering Petersburg from first the south and then the west.

For the next month Grant and Lee find themselves stalemated outside Richmond and Petersburg. Lee tries to break the siege by ordering Jubal Early to follow up his victories over David Hunter in the Shenandoah Valley and threaten Washington, but Grant’s rapid redeployment of VI and XIX Corps heads off disaster. It being an election year, Grant is not content to sit and wait. But it is left to a regiment along Burnside’s front to devise a possible solution to his problem.

At one point the Confederate line comes very close to the Union trenches: That area is at Elliott’s Salient. Brig. Gen. Stephen Elliott commands a brigade that has been brought up from South Carolina. Holding the center of the line here are the 18th and 22nd South Carolina along with four cannon of Pegram’s Virginia Artillery. You would not want to be in those units, because your days on Earth are numbered.

Belonging to Robert Potter’s IX Corps division is Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants. He leads the 48th Pennsylvania, which was raised in and around Schuylkill County. These men are all experienced anthracite coal miners. Knowing this, Pleasants comes up with an idea of how to break the stalemate that’s developed since June 18 and the failure of the Wilson-Kautz cavalry raid and the II and VI Corps’ muffed opportunity to break up the Weldon Railroad and the Jerusalem Plank Road.

Pleasants plans to drive a gallery underneath the Confederate line. The gallery will be five feet high, four feet wide at the base, and two feet at the ceiling. The army engineers do not think much of the plan, and they refuse to give Pleasants’s people mining shovels to do the work. So, they use ordinary shovels, cutting the handles down to make them shorter. They improvise wheelbarrows. They plan to dig a gallery a distance of 511 feet.

The soldiers begin digging. At a hundred feet they reach a point where they need to ventilate the gallery. They construct a wooden tube eight inches square; as they dig toward the Confederate line they lay the duct on the floor of the tunnel. They next drive a vertical shaft to the surface and place an airtight bulkhead between where they are digging and the bottom of the gallery. Then they start a fire next to the vertical shaft, and as the heated air rises to the surface it draws fresh air into the tunnel through the duct.

The Confederates hear the miners as the tunnel gets closer to their lines. Brig. Gen. Porter Alexander becomes suspicious of what the Yankees are about. He decides to have his men sink vertical countermines to locate the gallery. If they hit the gallery, they can employ charges of black powder to destroy it, along with the Union miners. But the Confederates have bad luck. Before Alexander can take countermeasures, he is wounded. His fellow Confederates fail to appreciate the danger. When they finally focus on the threat and sink four countermines, it is too late.

Pleasants’s people began work on the gallery on June 25; by July 23 they have reached the area under the Confederate works. They dig two lateral galleries perpendicular to the main tunnel, in which they will place the explosive charges. These lateral galleries are dug for a distance of 40 feet on each side of the main tunnel. Each lateral contains four magazines. They place a thousand pounds of powder in each magazine. They have difficulty again when they fail to obtain 8,000 pounds of first-grade powder. Nor are they given continuous fuses, so they have to splice ten-foot lengths of fuse.

During the siege of Petersburg, Union forces employed “the Dictator” or the “Petersburg Express” a 13–inch, 17,000–pound mortar, to shell the city from over two miles away.

Burnside has four infantry divisions. The three white divisions have pulled heavy duty in the trenches, losing an average of 30 men per day. Burnside plans to use the black division commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero in the attack. Ferrero’s men spend several weeks practicing what they will do when the mine explodes. The first thing is to move forward immediately, to take advantage of the shock and confusion created by the initial explosion. And they are to stay out of the crater created by the blast. They are to pass to the north and south of the crater, avoiding it at all costs, as they press ahead. Their mission is to seize the high ground and secure a lodgment on the Jerusalem Plank Road.

On July 28, the mine is ready. Burnside notifies headquarters. It is the first Grant and Meade have heard of his plan. Grant prepares a diversionary attack to draw the Confederates’ attention away from this sector of the front by sending Sheridan’s cavalry and Hancock’s corps north of the James River to attack Deep Bottom. When Meade learns details of Burnside’s plan, he becomes concerned about what will happen if the attack fails and the black division is slaughtered. If disaster ensues, he believes he will be accused of sending the blacks to certain destruction. He refers the situation to Grant, who on reviewing it sides with Meade. That means the men who have been training to lead the assault are not going to. Burnside makes an even worse decision by allowing James Ledlie’s white division to have the lead. The choice is made by drawing straws. Not only is Ledlie the most incompetent division commander in IX Corps, experience has shown that he is the poorest choice for the critical mission in the Armies of the Potomac and the James.

The Union high command alerts all parties on July 29 that at 3:30 the next morning they will detonate 8,000 pounds of powder under Elliott’s Salient. Hancock’s men, returning from north of the James, take position on the right of Burnside’s corps; Warren’s corps on Burnside’s left is alerted to be ready to join in the attack. Union artillery is massed and ready to hammer the area north and south of the crater. Ledlie’s men move up and take position just behind the Union picket line, going to ground concealed from the Rebels’ view. Ledlie’s two brigades are led by Col. Elisha Marshall and Brig. Gen. William Bartlett. Bartlett is my favorite because he will lead his men into action with one cork leg. He has lost his right leg between the hip and the knee. The men have not been issued scaling ladders nor have they been given any specific instructions as to what to do when the mine explodes. In short, nothing has been done to properly prepare Ledlie’s division to spearhead the assault once the mine detonates.

With the troops in position and ready to go, Colonel Pleasants enters the gallery and lights the fuse. After lighting the fuse, Pleasants comes out of the tunnel, and the Union troops anxiously wait for the big explosion. Everyone looks at their watches. Over in the 14-gun battery, Burnside waits. Crowded into the nearest approach trench, or sap, eight feet wide and six feet deep, is General Potter’s division. In the south approach trench, in a ravine 500 feet farther south, standing four abreast and extending back hundreds of yards, is Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox’s division. The blacks of Ferrero’s division, who were supposed to lead the attack, are some distance to the rear.

Maj. Gen. William “Little Billy” Mahone helped block the Federal assault during the Battle of the Crater after the Federals exploded a mine under Confederate fortifications.

The generals look at their watches; 3:30 a.m. comes and nothing happens. At 4:15 a.m. Pleasants calls for volunteers to enter the gallery and see what has gone wrong. Sgt. Henry Rees and Lt. Jacob Douty respond. They enter the gallery crouched low and discover that the fuse has gone out. They splice the fuse and relight it. It is supposed to ignite the 8,000 pounds of powder 15 minutes from the time they relight the fuse. They come out of the tunnel and wait. At 4:40 a.m. there is a huge explosion. The Earth seems to shake as a great geyser of earth, men, and artillery pieces are hurled into the air. Great clods of earth and debris rain down upon Ledlie’s people. They, unlike Ferrero’s blacks, have not been properly trained for what to expect when the explosion occurs. They do not do anything but stare in awe and amazement at the spectacle of devastation before them for some ten minutes. Finally the men move forward. Ledlie will not go with his men. Instead, he retreats to the protection of a bombproof and pulls out his bottle and begins to indulge.

When the mine explodes it devastates much of Elliott’s Salient, kills or maims 280 Confederates, wrecks four cannon, and creates a Crater 170 feet in length north to south, 30 feet deep, and 60 feet wide. The Crater has been partially filled in and the landscape molded and sodded in the years since.

Unlike the Union leadership, General Lee and key Confederate subordinates are not paralyzed by what could for them have been a disaster. Lee rides to the area and takes position on high ground near the Jerusalem Plank Road. From here he can see the scene and call up reinforcements and throw them into the fight when and where needed. Col. John T. Goode’s 59th Virginia to the south takes position facing the Crater. Supporting Goode’s Virginians and Elliott’s South Carolinians who have survived the blast are the cannoneers of Davidson’s Virginia Artillery from a position 400 yards south of the Crater. A similar distance to the north are sited four cannon manned by Wright’s Virginia Artillery. The gunners hammer the ground between Ledlie’s jumping-off point and the Crater with a storm of canister and spherical case shot. The Confederates, like they had at Spotsylvania on May 10 and 12, have taken action to shore up the flanks of the gaping hole in their fortifications torn by the explosion of the mine.

After Cold Harbor, Grant crossed the James River and moved against Richmond’s rail center at Petersburg. The initial Federal attempt to break into the city on June 15 failed, and Lee by June 18 shifted his army to reinforce Beauregard in the formidable Confederate works ringing the city. Grant was forced to begin siege operations. On July 30, 1864, Union forces attempted to break into the city by exploding a mine under part of the Confederate works, but the battle ended in a bloody repulse for the Federals. Throughout the summer and fall Grant extended his left to the south and west to sever Lee’s supply lines, forcing the Confederates to extend their fortifications westward. Siege operations lasted through the bitter winter of 1864–65.

The Yankees approach the Crater and are mesmerized by what they see. They haven’t been warned by their officers and NCOs to avoid the Crater. They should have been told to pass the Crater to the north and south and press on to the Jerusalem Plank Road as quickly as possible. But leaderless without their division commander, they crowd into the Crater. Some good Samaritans rescue partially buried Confederates. Some duck for cover from the small-arms and artillery fire that is beginning to be brought down upon them from Confederates ensconced on either side of the Crater.

Moving up in support is Bob Potter’s two-brigade division. They crowd in upon Ledlie’s people. Few soldiers attempt to pass around the terrible pit. Willcox’s division comes forward to suffer a similar fate. Soon, there are thousands of bluecoats milling about in the Crater. Too late, Burnside commits Ferrero’s division, composed of Col. Joshua K. Sigfried’s and Col. Henry G. Thomas’s brigades. They seek to do what they were trained to do: Pass to the north and south of the Crater. By now the Confederates have had two hours to recover from the shock of the explosion. Col. John Haskell has arrived with two 24-pounder coehorn mortars, a high-trajectory weapon; his men arch shells into the Crater from point-blank range.

Arriving on the scene is the first of the Confederate reserves that Lee has rushed. They belong to William Mahone’s III Corps division. “Little Billy” Mahone is an 1849 graduate of VMI and weighs 110 pounds. He had been a journeyman soldier in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia until 1864’s Overland campaign. A hypochondriac, he travels with a cow and chickens so he can have milk and eggs daily. He counterattacks, first with his former brigade of Virginians now led by Brig. Gen. David Weisiger, a Petersburg native. There is more flagrant killing of blacks by whites and whites by blacks than there was at Fort Pillow. It is bloody combat of the worst kind. Mahone now sends in Brig. Gen. Ambrose “Rans” Wright’s Georgians, who charge into the Crater.

About this time Grant and Meade arrive on the scene, and they see what is happening. They are unhappy with the way Burnside is running the show and order him to withdraw his men. Meanwhile, General Ferrero has joined Ledlie in the bombproof, and they both imbibe “John Barleycorn” as their men are cut to pieces.

By noon, boyish-faced Brig. Gen. J. C. C. Saunders’s Alabama Brigade arrives. There are now too many Rebels surrounding and pummeling the Yankees hemmed in and around the Crater. They charge the Federals. The Union troops break. General Bartlett’s cork leg is shattered by a Confederate shell, and he cannot escape. It is a grim day for the Union cause. There are more than 4,000 Union casualties, with 1,100 men killed outright and 2,900 either wounded or captured. This will be the last frontal assault Grant will undertake against the Petersburg and Richmond defenses until Sunday, April 2, 1865.

The Confederates reoccupy the Crater and throw up a new line of earthworks to its rear. If the Union troops had reached the Jerusalem Plank Road, Petersburg might well have fallen that day. The war would probably have soon ended and the lives of thousands doomed yet to fall saved.

For the next seven months, Grant will probe north and south of the James River, stretching Lee’s lines, looking for weak spots. Several times it seems as if he might prevail at last; each time Lee hangs on, and in some cases delivers a punishing counterblow. The two titans have battled each other to a draw, but Grant has pinned Lee to the Confederate capital, effectively taking him out of the war. In the past, the Confederate commander could be counted on to do something daring. Now he finds himself sitting and waiting.