OCTOBER 1859

During the “four score years” that followed the founding of the American Republic, the persistent question of whether slavery should be tolerated in a society that promised equality and professed democratic ideals had become more and more divisive politically. Confrontations between the free states of the North and the slaveholding, agrarian South increasingly gave way to violence and force of arms. By mid-century three decades of constitutional argument and legislative debate had led to the Compromise of 1850, a series of stopgap measures that temporarily balanced the interests of slave and free factions. In 1854, when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, opening up two new western territories for settlement, it left to “popular sovereignty” the decision whether slavery would be allowed to expand into these new lands. In other words, the white male inhabitants of the territories would decide for themselves. Northerners and Southerners alike soon rushed westward, determined to control the political processes of the new territories. Both sides were armed, and before long a vicious guerrilla war broke out between pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” and free-soil “Jayhawkers.” In describing the anarchy, eastern press headlines screamed “Bleeding Kansas.”

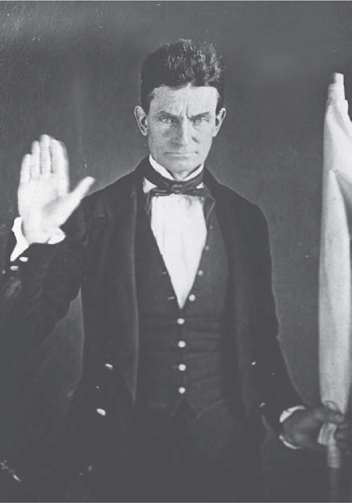

One of the leading figures in this bloodshed was militia captain John Brown, who had established a free-soil settlement on the Osawatomie. An ardent abolitionist who grasped his inspiration from the stern and vengeful God of the Old Testament, Brown took it upon himself to strike back at members of the pro-slavery faction after some of their number had attacked the antislavery stronghold of Lawrence, Kansas, on May 21, 1856. Three days later, on the night of May 24, Brown and several of his numerous sons attacked a pro-slavery community called Dutch Henry’s Crossing along Pottawatomie Creek and seized and murdered five men in cold blood. Pro-slavery forces later struck back, attacking the settlement of Osawatomie on August 30, killing one of Brown’s sons and burning his home.

Although authorities claimed to want Brown apprehended, he remained free and somewhat elusive, but eventually was forced out of Kansas. As the decade neared its end, he was addressing groups in the East, rallying them to the abolitionist cause with passionate rhetoric. At the same time, however, Brown began to talk privately about the possibility of instigating a slave insurrection. He believed that the Federal arsenal and armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, offered a promising initial target; if he could secure enough arms and begin to rally escaped slaves to seek out a secure stronghold, a freedman’s “republic” in the Appalachian Mountains, he might well create a rebellion that would spread and liberate slaves throughout Virginia and the South.

At Harpers Ferry the Potomac receives the waters of the Shenandoah River. To the west of town is Bolivar Heights, part of the Blue Ridge Mountains. South of the Shenandoah (an Indian term meaning “Daughter of the Stars”) and south of the Potomac is Loudoun Heights, part of the Blue Ridge Mountains. North of the river, in Maryland, are Maryland Heights and South Mountain. At Harpers Ferry the river valleys of the Potomac and Shenandoah form natural routes of travel. Anthropologists believe that long before the coming of whites, Indians moving north and south were in the habit of crossing the Potomac River in and around the Harpers Ferry area.

Harpers Ferry is named for Robert Harper, who in 1747 began operating a ferry across the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. He established himself there at a good time for an entrepreneur. He saw the beginning of a heavy migration from the northeast to the southwest, opening up the area down the Shenandoah Valley toward western North Carolina. That same year, Dr. Thomas Walker, an English chap, traversed an ancient Indian trail through a defile in the Appalachians and named it Cumberland Gap, by way of which hundreds of settlers were able to reach Kentucky, including Daniel Boone. The crossing at Harpers Ferry soon became just as important a travel route for the white man as it had been for the Indians.

The Shenandoah River runs into the Potomac at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Strategically important for travelers heading West, the town was home to the Federal armory and arsenal.

Young George Washington becomes familiar with the lands to the west of the Blue Ridge as a surveyor. The French were beginning to move aggressively southward from Canada, in what would become the French and Indian War, and establish Fort LeBoeuf on the portage between waters draining into Lake Erie and the stream forming the headwaters of the Allegheny. Washington passes through this area in 1753 as a 22-year-old with a message from Virginia Lt. Governor Robert Dinwiddie telling the French commandant at Fort LeBoeuf that he is trespassing on territory chartered to England in 1609 and must withdraw. The French are unimpressed with this message. The next year, Washington leaves Williamsburg with a small detachment, passes through Harpers Ferry, and proceeds westward. About 20 miles east of the confluence of the rivers forming the Ohio, Washington builds a fort at Great Meadows, which he calls Fort Necessity, having learned that the French have already arrived at the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers. Washington is lucky. His men ambush a force of Indians and Frenchmen commanded by Ens. Joseph Jumonville. Washington’s Indian allies ritually murder Jumonville by smashing his skull and removing his brains. Jumonville’s brother responds by leading an attack against Fort Necessity, forcing Washington to surrender. Fortunately for what will become the United States, the Frenchman controls his Indians, and they do not murder our future President. Washington will come back through this area with Maj. Gen. Edward Braddock in an attempt to oust the French from Fort Duquesne, near modern Pittsburgh, but the British are badly beaten and withdraw in July 1755.

Washington buys land in the country surrounding Harpers Ferry. By 1791, as President of the United States, he’s in a position to do something for the region. It’s been decided by Congress that the future capital of the United States will be sited just below the falls of the Potomac River, in what will be called the new District of Columbia. As a military man, George Washington looks to establish an armory nearby. The only other one in the United States is at Springfield, Massachusetts.

Now, it’s important to distinguish between an armory and an arsenal. You manufacture arms at an armory; you store arms and repair them at an arsenal. The new armory must be near a source of water power, and relatively close to the capital. Washington decides to site the second U.S. armory at Harpers Ferry, 61 miles northwest of the capital.

Washington also has an interest in economic development and will be a force behind the Potomack Canal, which precedes the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. The Potomack Canal is planned to provide water routes around the obstacles of Great Falls and Little Falls. Through its militia system, the United States had established arsenals as well: The one in Virginia is located here, so Harpers Ferry will have both an arsenal and an armory. By 1859 Harpers Ferry is also the intersection of two major railroads, the Baltimore & Ohio and the Winchester & Potomac. Because it’s at the hub of strategic transportation corridors, with an armory and an arsenal situated near the Mason-Dixon Line, the accepted divider between slave and free states, Harpers Ferry becomes a key objective as John Brown matures his plans. It is a gateway to and from the slaveholding South.

John Brown was born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, but grew up in Ohio, where his abolitionist father maintained a stop on the Underground Railway. Up until his antislavery activities in Kansas, John Brown was far from successful in life except at fathering children. By two women he fathered twenty children, seven by his first wife and the rest by his second. Largely thanks to his notoriety in Bleeding Kansas, Brown becomes something of a hero among abolitionists in Massachusetts and the other New England states. He is closely associated for a while with the former slave Frederick Douglass. However, when the self-educated Douglass learns of Brown’s plans to organize an Army of Liberation to support a slave insurrection, he urges caution. “An attack on the federal government,” Douglass argues, “would array the whole country against us.”

Brown arrives in Harpers Ferry on the second day of July 1859 and will identify himself variously as Isaac Smith, Nelson Hawkins, and Shabel Morgan. He talks to some local people and says he wants to rent an isolated farmhouse. They tell him about the Kennedy place, which is located in a secluded valley on the west side of Elk Ridge, five miles northwest of Harpers Ferry. He rents it and begins to assemble his Army of Liberation. Brown arrives in Harpers Ferry with his sons Owen and Oliver. He is soon joined by Oliver’s wife Martha, his son Watson, and 16-year-old daughter Annie. The other Army of Liberation volunteers drift in. Another veteran of Kansas, the well-educated John Henry Kagi will be secretary of state for Brown’s provisional government. Initially, they have an English soldier of fortune, Hugh Forbes, who had fought with Garibaldi in Italy, prepare a plan for guerrilla warfare that will free slaves. Forbes presents Brown with his plan, called “the drill manual,” but never actually visits the Kennedy Farm. While on a speaking tour in Connecticut, Brown contracts to have one thousand pikes—long, spear-like instruments—made. With Kagi’s help, Brown had drafted a “Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States” in 1858. After about a month and a half Forbes decides this is a crackbrained idea and that Brown is a madman. He quits in August.

Brown is now confronted by a mutiny in his army. The soldiers are discontented with the long periods of confinement and inactivity on the farm. Frederick Douglass urges that they call the raid off, but Brown is a charismatic speaker. He addresses the army. The army agrees to stay. There are five blacks in the army. They can only come out at night—Virginia and Maryland are slave states. What are the neighbors going to say if they see unfamiliar whites and blacks running around together during daylight hours? The blacks have to stay up in the Kennedy farmhouse garret. A number of the whites are Quakers. Quakers eschew violence, but some have come to the conclusion that violence in liberating the slaves can be justified by their church. Others had followed Captain Brown in Kansas. Brown is going to sleep 23 people in the Kennedy house, 25 counting Annie and Martha.

Brown sends out John E. Cook to pose as a book salesman, aiming to ingratiate himself with Lewis Washington, great-grandnephew of George. He visits Washington in his home, Bellair, and scouts out his house. During their actual raid Captain Brown will send Aaron Stevens with five people to seize Lewis Washington as a hostage, and Cook goes with them.

Six leading members of the abolitionist movement, five of them from Massachusetts, fund Brown’s uprising. We know them now as the Secret Six. There is Samuel Gridley Howe, a world-renowned physician and the husband of Julia Ward Howe. There is clergyman and writer Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a leader in the intellectual community in Massachusetts who will command a black regiment during the Civil War. Manufacturer George Stearns is another—he will be in charge of recruiting blacks when the Lincoln Administration starts organizing black units in 1863. Franklin Sanborn is a Boston editor and educator. Theodore Parker is a prominent Boston Congregationalist minister. They are joined by former antislavery Congressman Gerrit Smith of New York. These are the Secret Six.

By mid-October Brown feels that the time has come to strike. Concerned about arousing the suspicions of neighbors around the Kennedy farm, Brown feels compelled to act despite the fact that several members of his “army” have not yet arrived. On the evening of October 16, 1859, he turns out his army.

Brown tells his men to get “on your arms.” Owen Brown, Francis Merriam, and Barclay Coppoc remain at the Kennedy farm with most of the army’s pikes and guns, as well as a number of incriminating letters that later will show that the raid is being funded by the Secret Six. The rest of his Army of Liberation, 19 strong including Brown, sets out for town. Brown knows it will be quiet in Harpers Ferry that night. There has been a revival meeting with singing, praying, and shouting, so the townspeople will retire early. Imagine Brown driving his wagon loaded with pikes and Sharps carbines down the hill leading to the Potomac. He sees the lights flickering off in Harpers Ferry as the last of the “night owls” go to bed. Brown knows it was a Methodist revival. It would have been better if it had been a Baptist revival, because the Baptists are generally a lot more fervent than Methodists. He sends John Cook and Charles Tidd to cut the telegraph line that leads to Washington and Baltimore.

About 11:30 Brown reaches the long covered bridge crossing the Potomac. Bill Williams, the bridge watchman, waiting to be relieved at midnight, is sitting in a guard shack on the Harpers Ferry side of the river. He hears men coming toward him, and he accosts them. They are wearing heavy shawls and slouch hats. Brown confronts Williams as two of his men put pistols in his face and overpower him. Williams asks “What have I done?” Brown replies “You’ve done nothing to me but enough to the poor blacks. I mean to capture Harpers Ferry, and if resisted I must burn the town and have blood.” So, trussing Williams up, they go to the armory gate. There Danny Whelan, the 17-year-old gatekeeper, a good Catholic boy, is confronted and captured as he whispers a prayer. The lock and chain are broken and Brown seizes the armory. Brown then sends five men out with his wagon, guided by John Cook and led by Aaron Stevens, to seize hostages. An important hostage will be Lewis Washington, descendant of the first President. In the early morning hours of the 17th, they break into his house and into his bedroom. Washington recognizes Cook. They tell him to get ready to come with them, but they want two things that he owns. They want the sword given George Washington by Frederick the Great that bears the inscription “From the World’s Oldest General to the World’s Greatest,” and a pistol that had belonged to Lafayette. Stevens, a veteran of Bleeding Kansas, points to Osborne Anderson and tells Washington, “Give him the sword.” Anderson is one of the five blacks who march with Brown. They take Lewis Washington, who dresses immaculately but refuses to ride in the wagon. They also seize his slaves.

Ardent abolitionist John Brown, pictured here in a circa 1846 portrait, led a violent antislavery attack in Kansas in 1856 before planning to instigate a slave rebellion in Harpers Ferry.

Brown hopes that as soon as the slaves have heard that he has possession of Harpers Ferry, they will rise up and spark a servile insurrection. But this is not the Deep South, where slavery exists in a far harsher form, and the blacks might well have swarmed to him. If slavery is ever less demeaning and arduous, it’s in this part of the nation. This is not a Louisiana sugar plantation or Mississippi cotton country. These are household slaves. Brown has not picked a good place to begin an insurrection.

The Lewis Washington slaves get into the wagon. The raiders stop at the Allstadt House, where they seize John Allstadt and his son and take their six slaves. By the time they return to Harpers Ferry there has been bloodshed. The eastbound express comes in at 1:30 a.m. Dr. John Starry hears the chuffing of an engine idling and hears a shot. Like a good physician he grabs his medical bag and heads down toward the railroad depot, located adjacent to the Wager House Hotel. He finds a badly wounded man, Hayward Shepherd, a free black who works as a baggage man. He has been shot in the groin by one of the raiders; it’s obvious to Dr. Starry that he’s not going to live long. So the first man killed by the Army of Liberation is one of the very people they’ve come to liberate.

Now it is 5 a.m. and Brown and his raiders have stopped a Baltimore & Ohio train. When conductor Andy Phelps asks, “Can I proceed?” Brown, concerned about innocent travelers, says yes, but the conductor is worried. Perhaps the raiders have sabotaged the bridge, so Brown gets a lantern and leads the train across the bridge. Phelps stops the train at the Monocacy Junction station, where the telegraph line is operational, and sends a message warning, “Insurrectionists are in possession of Harpers Ferry.”

It was not an auspicious beginning. By stopping the train, then letting it proceed, Brown ensured that people would too quickly learn of his raid. Still, Brown had succeeded in securing control of the bridge leading into town; before long both the arsenal and armory were under his control, along with the nearby Hall’s U.S. Rifle Works. He took control of a small group of prisoners, including several armory workers who showed up early on the morning of October 17. But his success was short-lived. Dr. Starry quickly spread the word as to what had happened; militia companies from Virginia and Maryland began to converge on Harpers Ferry. Some townspeople also picked up weapons and joined in the fray. Before midday they had reclaimed control of the bridge and begun advancing on key points. Brown attempted to negotiate a truce, but those efforts failed, and by afternoon several members of his army were killed, captured, or wounded as local townsfolk and militia tightened their circle around the survivors of Brown’s beleaguered band.

Brown and a number of his remaining men take refuge in the armory engine house. The armory has a brick wall around it. The engine house is located near two arsenal buildings situated close to the foot of Shenandoah Street, on the south side of the armory. Here the authorities keep their fire engines, but the building would gain fame as John Brown’s Fort.

Before long, there is more bloodshed in the town. Dr. Starry, after treating Shepherd, goes up to the Lutheran Church and tolls the bell and sends messengers to nearby Charles Town and Shepherdstown. The word spreads—insurrectionists are in possession of Harpers Ferry. The militia turns out, but it’s not particularly well organized or disciplined. Shortly after 9 a.m. Thomas Boerly, a local grocer, is shot by a raider as he walks down High Street; there he lies with his blood flowing into the gutter. Ex-West Pointer and candidate for sheriff of Jefferson County George W. Turner is gunned down as he rides along High Street. Also shot is the friendly, popular, 72-year-old Mayor Fontaine Beckham, who is the guardian of a black family and a black man who will be freed upon his death. They will be the only blacks liberated by the raid, winning their freedom when Beckham’s will is probated. A number of the raiders have also been killed—Dangerfield Newby, a black man whose wife and family are held in bondage in Virginia and the oldest of the raiders next to Brown; William Leeman; John Kagi; Lewis Leary (black); and William Thompson. Aaron Stevens has been wounded and John Copeland (black) captured.

As darkness closes in, Brown is barricaded in the engine house. The raiders in John Brown’s Fort with the “old man” are Dauphin Thompson and Jeremiah Anderson; Oliver and Watson Brown, both mortally wounded; Stewart Taylor, who will be killed sometime during the long night; Shields “Emperor” Green (black); Edwin Coppoc; and 11 hostages, including Lewis Washington and the Allstadts, father and son. A number of the “liberated” slaves have been reluctantly armed with pikes.

During the long night Watson Brown dies; when John Brown hears his other son, Oliver, moaning, he snaps, “Shut up and die like a man.” Before long Oliver dies.

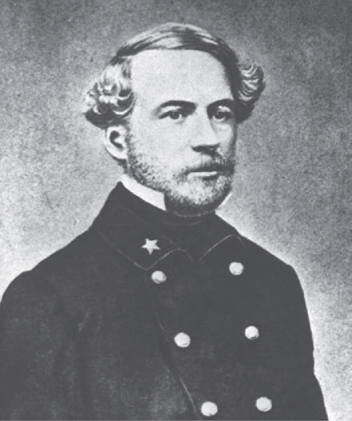

News that something bad has happened at Harpers Ferry arrives at the War Department in Washington City on the morning of October 17. Upon hearing the news President James Buchanan goes to the War Department. In the office that day is James Ewell Brown Stuart, a lieutenant in the First U.S. Cavalry on leave from Fort Riley in Kansas Territory. He’s in Washington seeking to patent an invention to hitch a saber to a belt. There is only one senior line (combat) officer of the U.S. Army in Washington. Every other one is a staff officer. The only line troops in Washington are at the Marine barracks. Already the Navy Department has been alerted, and Lt. Israel Green with some 90 marines boards a special train en route for Harpers Ferry. Stuart is sent to find Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, who is known to be at Arlington, his wife’s family home, on a long leave of absence to settle his father-in-law’s estate. Stuart finds Lee in civilian clothes at Ledbetter’s Pharmacy in Alexandria. Reporting to Secretary of War John B. Floyd and the President, Lee receives orders to proceed to Harpers Ferry and take charge of the marines. The marines had been ordered to halt and detrain at Sandy Hook, a mile and a half downstream on the Potomac. Lee will not arrive at Sandy Hook until after dark on the 17th.

By the morning of October 18, Colonel Lee, having crossed the river, deploys Green and his marines in front of Brown’s Fort, and orders the saloons closed. He asks the commander of the Virginia militia, “Will you storm the engine house?” The reply is no: The militia will leave that job to the professional military. Lee then approaches Col. Edward Shriver and asks if the Maryland militia would like to seize the engine house. Shriver gives the same reply. It’s going to be up to Colonel Lee, Lieutenants Green and Stuart, and the marines to get the insurrectionists out.

No one knows that it’s the John Brown who’s in the engine house; everyone still assumes it’s a man named Isaac Smith. Lee directs Stuart to approach the engine house, white handkerchief in hand, and parlay with the leader of the insurrection. Lee adds that if they surrender and do not harm the hostages, he will guarantee their safety as prisoners. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Green has formed up a detail of marines with sledgehammers, in case they have to storm the engine house. As Jeb Stuart nears the engine house, the door opens a crack and Stuart is surprised by who he sees. Having been stationed at Forts Leavenworth and Riley, in Kansas Territory, Stuart recognizes “Old Osawatomie” Brown, as he was known there. He tells Brown of Lee’s terms. Brown says, “Let me march out with my army. Let me cross the bridge, and I’ll keep the hostages until we get across the bridge, and then I will release them unharmed.” Stuart’s orders are not to negotiate. He steps back from the door and waves his hat—the signal to storm the engine house. A team of brawny marines comes forward with sledgehammers and attacks the engine house doors, but there is too much give in the doors, and the planks do not shatter. Green then sends forward a team of marines with a fire ladder. Using the fire ladder as a battering ram, they batter away part of the lower corner of one of the doors.

On October 17, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee (pictured here in a circa 1855 photo that was later retouched) received orders to take charge of the marines at Harpers Ferry and stop the insurrection.

Israel Green has brought with him a light dress sword rather than a heavier combat saber. He crawls through the door on his hands and knees, followed by other marines. As he crawls through the door he sees Brown, crouching, with his Sharps carbine. Lewis Washington points Brown out. Green rushes at Brown and puts a deep cut on his neck with his sword. Green then tries to run Brown through, only to have the blade strike a button or some other hard item and bend double. He then rushes at Brown and uses the blunt end of the broken sword to beat Brown into submission. He leaves Brown badly bleeding, slumped on the floor. One marine who was following behind him is mortally wounded, possibly by a shot fired by Brown, and a second is wounded in the brief melee. A marine lunges at Dauphin Thompson, pinning him to the wall with his bayonet. Thompson, with this bayonet through him, turns with his center of gravity and ends up pinned to the wall head downward. Jeremiah Anderson is shot and killed. Brown is captured alive, along with Coppoc and “Emperor” Green. On the floor are Stewart Taylor and Oliver and Watson Brown, who all died during the night from their wounds. None of the hostages is harmed.

Arriving here shortly after the capture are Senator James M. Mason and Governor Henry Wise, both of Virginia, and a busybody from Ohio, U.S. Representative Clement Vallandigham. They question Brown. Wise soon makes the worst decision, in my opinion, that any governor of any state has ever made. He claims Brown for the Commonwealth of Virginia, instead of having the federal government prosecute Brown for murder. Wise will have him charged as having committed treason against Virginia, and having conspired with slaves to foment servile insurrection. Wise is impressed when he questions Brown. Brown is outspoken and straightforward about himself and his objectives. Colonel Lee will remain in Harpers Ferry until they have transferred Brown and the other prisoners to Charles Town on October 19, where they will be jailed and held for trial.

Brown’s trial for insurrection and treason lasts from October 27 to October 31. Brown represents himself. The jury’s verdict is handed down, and on the second of November the judge announces the verdict—death by hanging—and sets December 2 as the date for this to be carried out.

There is a lot of noise among abolitionists that they will rescue Brown. It is rumored that abolitionist forces are assembling in Bellaire, Ohio. Brown sends word that “I don’t want to be rescued.” He knows he is going to be more valuable to the cause as a martyr than rescued. During the trial, Brown puts the institution of slavery on trial. On the day of his execution, Brown will write in a note handed to his jailer that he is “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

On the day Brown is to be executed, Colonel Lee is back at Harpers Ferry with a large force of federal soldiers to keep order. Mary Ann Brown is also in Harpers Ferry. She visits her husband on December 1, but she does not go to the hanging. The VMI Corps of Cadets also attends, its artillery contingent led by a Maj. Thomas J. Jackson. Also present is one who will be at center stage on April 14, 1865. Actor John Wilkes Booth was performing in Richmond and temporarily joins the Richmond Grays, a militia unit dispatched to Charles Town.

As Brown comes out of the jail, in a scene to be recorded in paintings and lithographs, legend has it that black women hold up their children to be blessed by Brown. He rides a half-mile from the jail to the hanging site. He mounts the 13 steps. The hangman ties his seven knots. Brown says, “Make it quick.” And he’s gone. Booth is impressed. He loathes everything that Brown stands for, but he’s impressed with the way Brown goes to his death. Would he remember this day in April 1865?

Repercussions sweep the country throughout the remainder of 1859 and into 1860. The publication of the trial transcript inflames people; so does the indictment in Virginia of the Secret Six. When authorities sent by Lee arrive and search the Kennedy farmhouse, they find the correspondence tying Brown to the Secret Six. To their horror, Southerners discover that what at first looked to be the action of a “madman” has been backed by responsible people in the North—leaders of the abolitionist movement and leading intellectuals. The Virginia court indicts them. The only one that flees the country is Theodore Parker. The others stay because they know that when the legal people deliver extradition papers, they will not be honored.

Many Southerners see Brown as an agent of abolitionists seeking to incite a servile insurrection in the South, such as had happened with severe consequences more than 50 years earlier in Haiti. Southerners also see that Brown is being aided and abetted by people that enjoy great public support in the North. Brown is looked on as a saint by millions of Americans, and by equal numbers as a madman, and yes, a terrorist. Southern legislatures vote large sums of money to buy arms and equipment; the pro-secession “fire eaters” strengthen their position in the southern states. If I’m a good Southerner at the time, I can see why I might decide to join the militia. To many, Brown has made his gallows as sacred as the cross and the crown of thorns worn by the Savior on Calvary. To most Southerners he is the devil incarnate.

Brown’s body is turned over to Mary Ann; she transports it northward with considerable show. Up in Philadelphia they ring the Liberty Bell. He is buried in North Elba, New York, on a farm purchased for him years before by Gerrit Smith.

The fate of the respective members of the Army of Liberation, as Brown called his followers, is as follows: Brown, 59, hanged. Annie Brown, 16, sent home. Martha, daughter-in-law, 17, sent home. John Kagi, killed in the Shenandoah River as he flees. Aaron Stevens, hanged. Oliver and Watson Brown, killed. Jeremiah Anderson, killed. John E. Cook, hanged. Charles Plumber Tidd, escaped. William Thompson, killed—shot, dumped in the river, and for days passersby could see his ghostly face looking up at them. Dauphin Thompson is bayoneted in John Brown’s Fort. Albert Hazlett, hanged. Edwin Coppoc, hanged. Barclay Coppoc, Francis Merriam, and Owen Brown, left as rear guard at the Kennedy farm, escaped. John Copeland, hanged. William Leeman, killed. Stewart Taylor, killed. Osborne P. Anderson, escaped. Dangerfield Newby, killed. Lewis Leary, killed in the Shenandoah River. Shields “Emperor” Green, hanged.

It is my belief that the Brown raid and its linkage with the Secret Six is the vital catalyst that leads to secession, the Civil War, and the liberation of more than four million black Americans.