Chapter 4

Organization

“… A good house is a single thing, as well as a collection of many, and to make it requires a conceptual leap from the individual components to a vision of the whole. The choices … represent ways of assembling the parts. … the basic parts of a house can be put together to make more than just basic parts: They can also make space, pattern, and outside domains. They dramatize the most elementary act which architecture has to perform. To make one plus one equal more than two, you must in doing any one thing you think important (making rooms, putting them together, or fitting them to the land) do something else that you think important as well (make spaces to live, establish a meaningful pattern inside, or claim other realms outside).”

Charles Moore, Gerald Allen, Donlyn Lyndon

The Place of Houses

1974

ORGANIZATION OF FORM AND SPACE

The last chapter laid out how various configurations of form could be manipulated to define a solitary field or volume of space, and how their patterns of solids and voids affected the visual qualities of the defined space. Few buildings, however, consist of a solitary space. They are normally composed of a number of spaces which are related to one another by function, proximity, or a path of movement. This chapter lays out for study and discussion the basic ways the spaces of a building can be related to one another and organized into coherent patterns of form and space.

SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS

Two spaces may be related to each other in several fundamental ways.

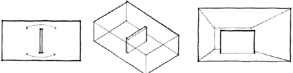

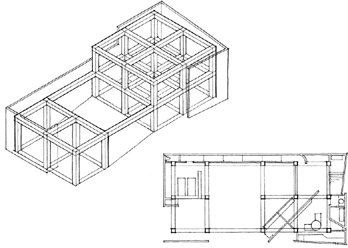

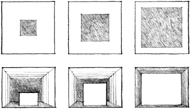

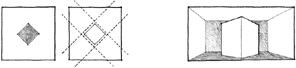

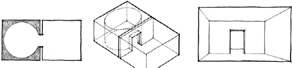

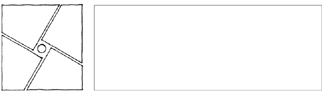

SPACE WITHIN A SPACE

A large space can envelop and contain a smaller space within its volume. Visual and spatial continuity between the two spaces can be easily accommodated, but the smaller, contained space depends on the larger, enveloping space for its relationship to the exterior environment.

In this type of spatial relationship, the larger, enveloping space serves as a three-dimensional field for the smaller space contained within it. For this concept to be perceived, a clear differentiation in size is necessary between the two spaces. If the contained space were to increase in size, the larger space would begin to lose its impact as an enveloping form. If the contained space continued to grow, the residual space around it would become too compressed to serve as an enveloping space. It would become instead merely a thin layer or skin around the contained space. The original notion would be destroyed.

To endow itself with a higher attention-value, the contained space may share the form of the enveloping shape, but be oriented in a different manner. This would create a secondary grid and a set of dynamic, residual spaces within the larger space.

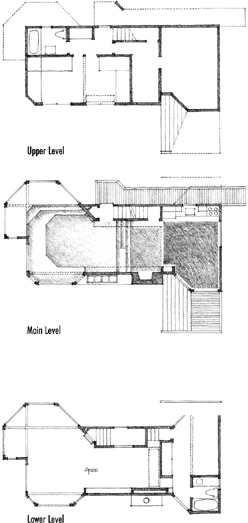

The contained space may also differ in form from the enveloping space in order to strengthen its image as a freestanding volume. This contrast in form may indicate a functional difference between the two spaces or the symbolic importance of the contained space.

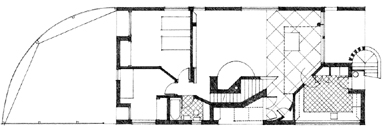

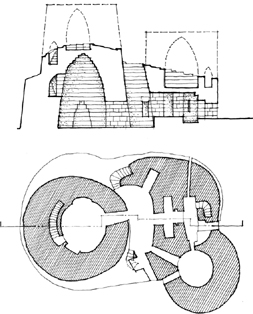

Moore House, Orinda, California, 1961, Charles Moore

Glass House, New Canaan, Connecticut, 1949, Philip Johnson

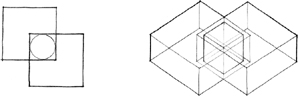

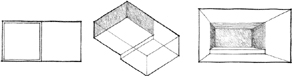

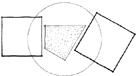

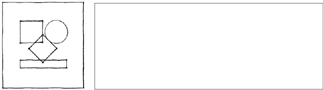

INTERLOCKING SPACES

An interlocking spatial relationship results from the overlapping of two spatial fields and the emergence of a zone of shared space. When two spaces interlock their volumes in this manner, each retains its identity and definition as a space. But the resulting configuration of the two interlocking spaces is subject to a number of interpretations.

The interlocking portion can merge with one of the spaces and become an integral part of its volume.

The interlocking portion can develop its own integrity as a space that serves to link the two original spaces.

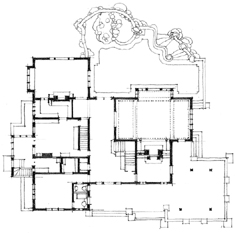

ADJACENT SPACES

Adjacency is the most common type of spatial relationship. It allows each space to be clearly defined and to respond, each in its own way, to specific functional or symbolic requirements. The degree of visual and spatial continuity that occurs between two adjacent spaces depends on the nature of the plane that both separates and binds them together.

The separating plane may:

• limit visual and physical access between two adjacent spaces, reinforce the individuality of each space, and accommodate their differences.

• be defined with a row of columns that allows a high degree of visual and spatial continuity between the two spaces.

• be merely implied with a change in level or a contrast in surface material or texture between the two spaces. This and the preceding two cases can also be read as single volumes of space which are divided into two related zones.

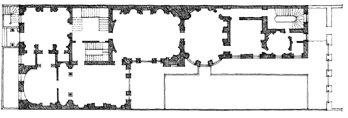

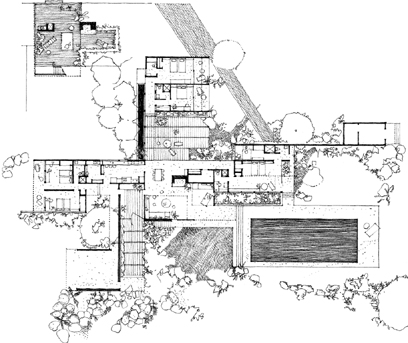

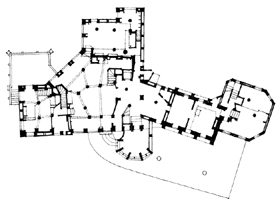

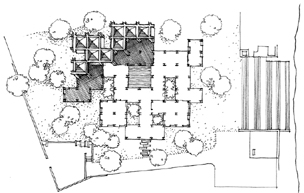

The spaces in these two buildings are individualistic in size, shape, and form. The walls that enclose them adapt their forms to accommodate the differences between adjacent spaces.

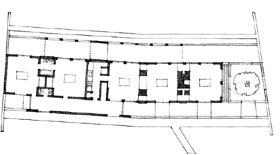

Three spaces—the living, fireplace, and dining areas—are defined by changes in floor level, ceiling height, and quality of light and view, rather than by wall planes.

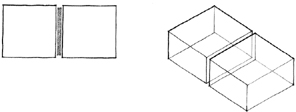

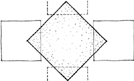

SPACES LINKED BY A COMMON SPACE

Two spaces that are separated by distance can be linked or related to each other by a third, intermediate, space. The visual and spatial relationship between the two spaces depends on the nature of the third space with which they share a common bond.

The intermediate space can differ in form and orientation from the two spaces to express its linking function.

The two spaces, as well as the intermediate space, can be equivalent in size and shape and form a linear sequence of spaces.

The intermediate space can itself become linear in form to link two spaces that are distant from each other, or join a whole series of spaces that have no direct relationship to one another.

The intermediate space can, if large enough, become the dominant space in the relationship, and be capable of organizing a number of spaces about itself.

The form of the intermediate space can be residual in nature and be determined solely by the forms and orientations of the two spaces being linked.

SPATIAL ORGANIZATIONS

The following section lays out the basic ways we can arrange and organize the spaces of a building. In a typical building program, there are usually requirements for various kinds of spaces. There may be requirements for spaces that:

• have specific functions or require specific forms

• are flexible in use and can be freely manipulated

• are singular and unique in their function or significance to the building organization

• have similar functions and can be grouped into a functional cluster or repeated in a linear sequence

• require exterior exposure for light, ventilation, outlook, or access to outdoor spaces

• must be segregated for privacy

• must be easily accessible

The manner in which these spaces are arranged can clarify their relative importance and functional or symbolic role in the organization of a building. The decision as to what type of organization to use in a specific situation will depend on:

• demands of the building program, such as functional proximities, dimensional requirements, hierarchical classification of spaces, and requirements for access, light, or view

• exterior conditions of the site that might limit the organization’s form or growth, or that might encourage the organization to address certain features of its site and turn away from others

Each type of spatial organization is introduced by a section that discusses the formal characteristics, spatial relationships, and contextual responses of the category. A range of examples then illustrates the basic points made in the introduction. Each of the examples should be studied in terms of:

• What kinds of spaces are accommodated and where? How are they defined?

• What kinds of relationships are established among the spaces, one to another, and to the exterior environment?

• Where can the organization be entered and what configuration does the path of circulation have?

• What is the exterior form of the organization and how might it respond to its context?

Centralized Organization

A central, dominant space about which a number of secondary spaces are grouped

Radial Organization

A central space from which linear organizations of space extend in a radial manner

Clustered Organization

Spaces grouped by proximity or the sharing of a common visual trait or relationship

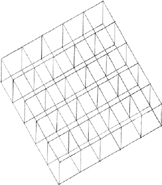

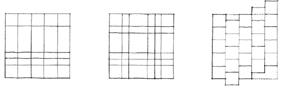

Grid Organization

Spaces organized within the field of a structural grid or other three-dimensional framework

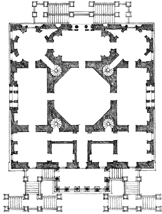

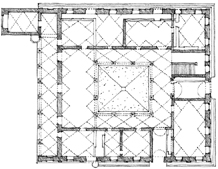

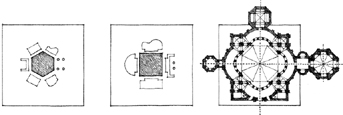

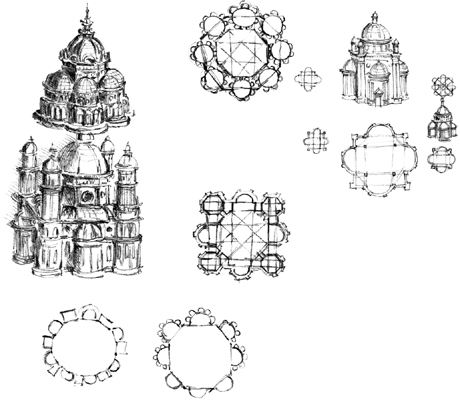

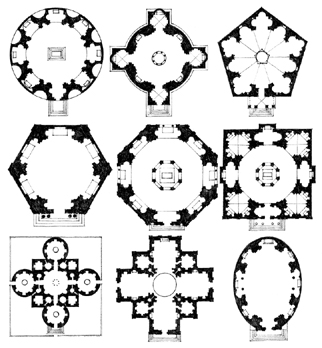

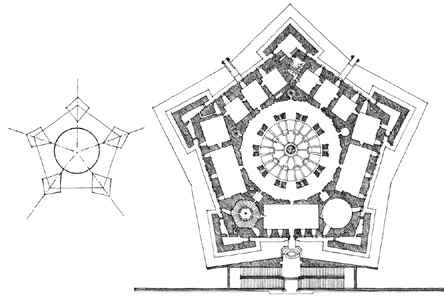

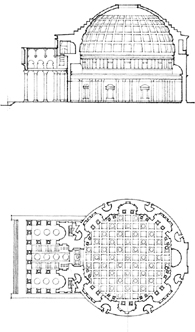

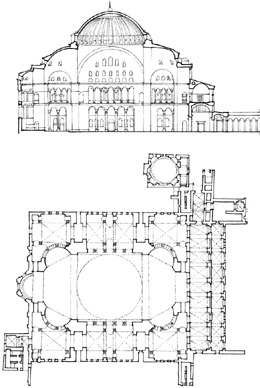

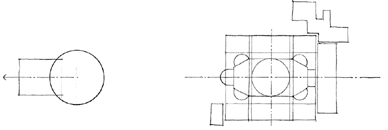

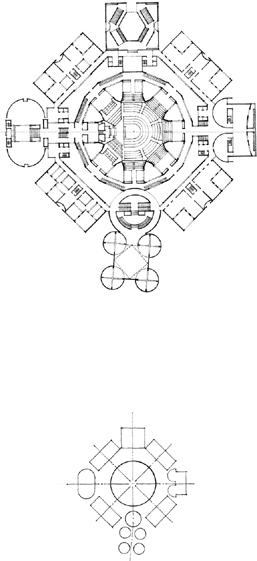

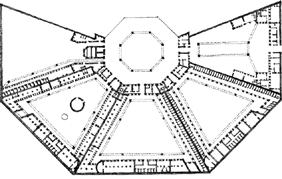

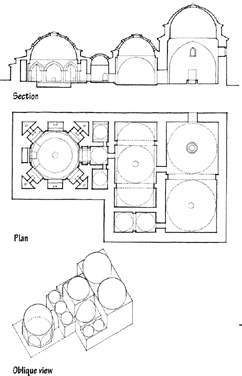

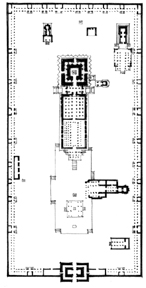

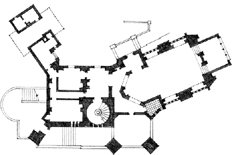

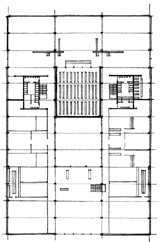

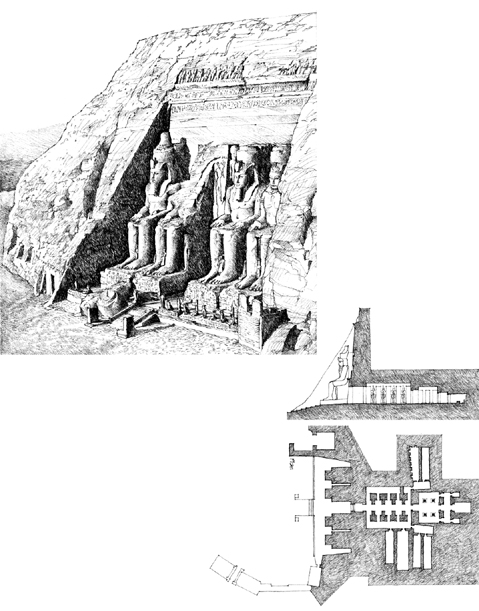

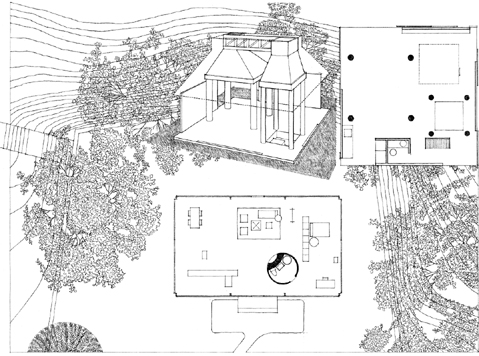

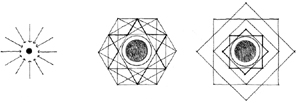

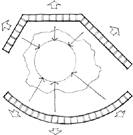

CENTRALIZED ORGANIZATIONS

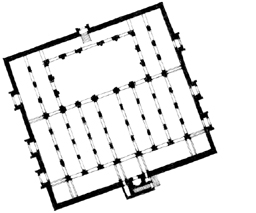

A centralized organization is a stable, concentrated composition that consists of a number of secondary spaces grouped around a large, dominant, central space.

The central, unifying space of the organization is generally regular in form and large enough in size to gather a number of secondary spaces about its perimeter.

The secondary spaces of the organization may be equivalent to one another in func-tion, form, and size, and create an overall configuration that is geometrically regular and symmetrical about two or more axes.

The secondary spaces may differ from one another in form or size in order to respond to individual requirements of function, express their relative importance, or acknowledge their surroundings. This differentiation among the secondary spaces also allows the form of a centralized organization to respond to the environmental conditions of its site.

Since the form of a centralized organization is inherently non-directional, conditions of approach and entry must be specified by the site and the articulation of one of the secondary spaces as an entrance or gateway.

The pattern of circulation and movement within a centralized organization may be radial, loop, or spiral in form. In almost every case, however, the pattern will terminate in or around the central space.

Centralized organizations whose forms are relatively compact and geometrically regular can be used to:

• establish points or places in space

• terminate axial conditions

• serve as an object-form within a defined field or volume of space

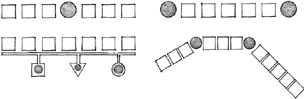

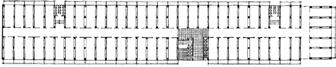

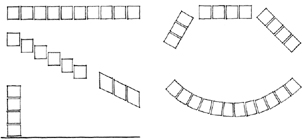

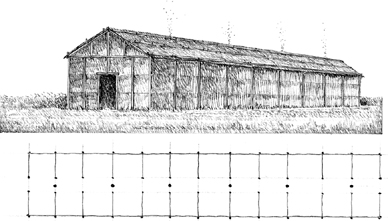

LINEAR ORGANIZATIONS

A linear organization consists essentially of a series of spaces. These spaces can either be directly related to one another or be linked through a separate and distinct linear space.

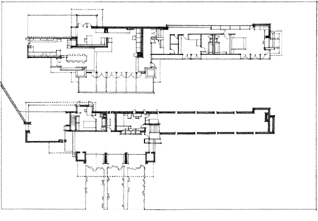

A linear organization usually consists of repetitive spaces which are alike in size, form, and function. It may also consist of a single linear space that organizes along its length a series of spaces that differ in size, form, or function. In both cases, each space along the sequence has an exterior exposure.

Spaces that are functionally or symbolically important to the organization can occur anywhere along the linear sequence and have their importance articulated by their size and form. Their significance can also be emphasized by their location:

• at the end of the linear sequence

• offset from the linear organization

• at pivotal points of a segmented linear form

Because of their characteristic length, linear organizations express a direction and signify move-ment, extension, and growth. To limit their growth, linear organizations can be terminated by a dominant space or form, by an elaborate or articulated entrance, or by merging with another building form or the topography of its site.

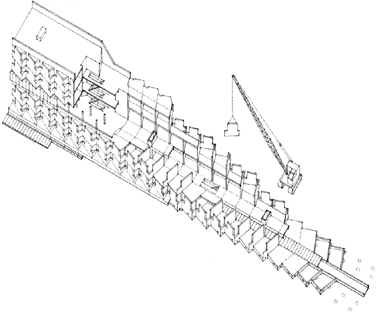

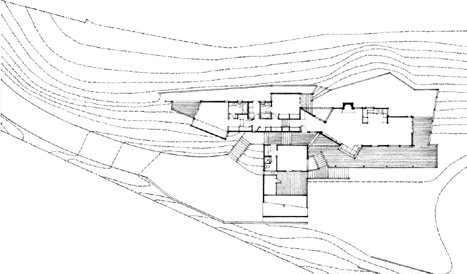

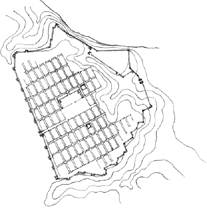

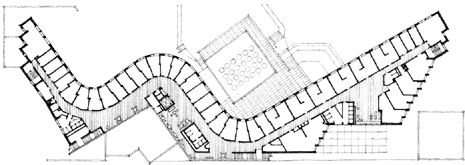

The form of a linear organization is inherently flexible and can respond readily to various conditions of its site. It can adapt to changes in topography, maneuver around a body of water or a stand of trees, or turn to orient spaces to capture sunlight and views. It can be straight, segmented, or curvilinear. It can run horizontally across its site, diagonally up a slope, or stand vertically as a tower.

The form of a linear organization can relate to other forms in its context by:

• linking and organizing them along its length

• serving as a wall or barrier to separate them into different fields

• surrounding and enclosing them within a field of space

Curved and segmented forms of linear organizations enclose a field of exterior space on their concave sides and orient their spaces toward the center of the field. On their concave sides, these forms appear to front space and exclude it from their fields.

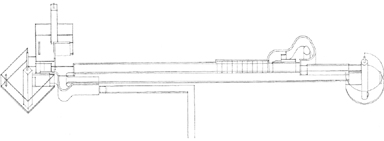

Longhouse, a dwelling type of the member tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy in North America, c. 1600.

Linear sequences of spaces

Linear sequences of rooms…

Introducing hierarchy to linear sequences…

and expressing movement

Linear organizations adapting to site…

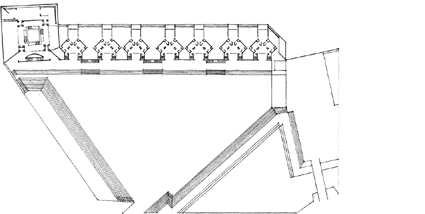

Typical Upper-floor Plan, Baker House, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1948, Alvar Aalto

Plan for the the Circus (1754, John Wood, Sr.) and the Royal Crescent (1767–75, John Wood) at Bath, England

and shaping exterior space

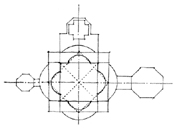

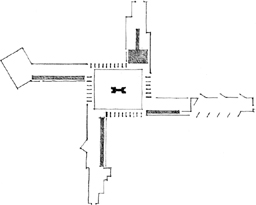

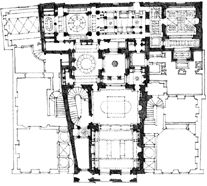

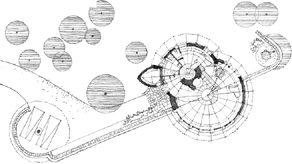

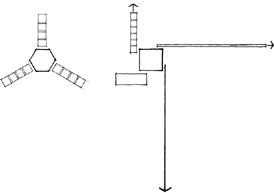

RADIAL ORGANIZATIONS

A radial organization of space combines elements of both centralized and linear organizations. It consists of a dominant central space from which a number of linear organizations extend in a radial manner. Whereas a centralized organization is an introverted scheme that focuses inward on its central space, a radial organization is an extroverted plan that reaches out to its context. With its linear arms, it can extend and attach itself to specific elements or features of its site.

As with centralized organizations, the central space of a radial organization is generally regular in form. The linear arms, for which the central space is the hub, may be similar to one another in form and length and maintain the regularity of the organization’s overall form.

The radiating arms may also differ from one another in order to respond to individual requirements of function and context.

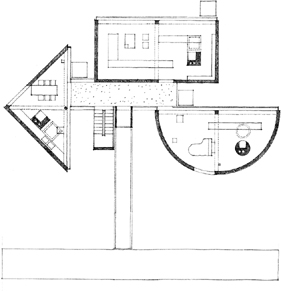

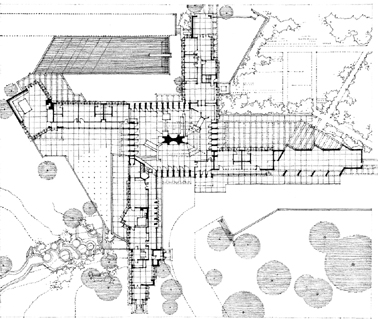

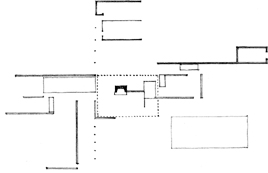

A specific variation of a radial organization is the pinwheel pattern wherein the linear arms of the organization extend from the sides of a square or rectangular central space. This arrangement results in a dynamic pattern that visually suggests a rotational movement about the central space.

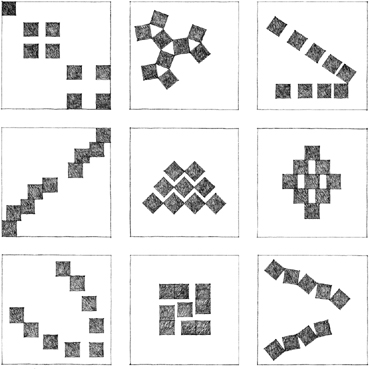

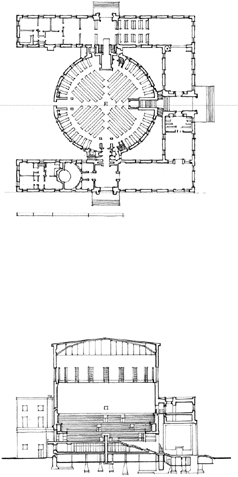

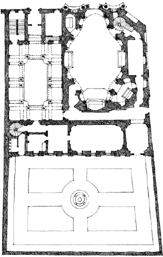

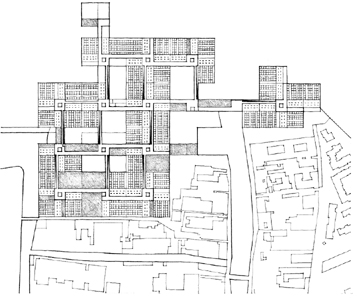

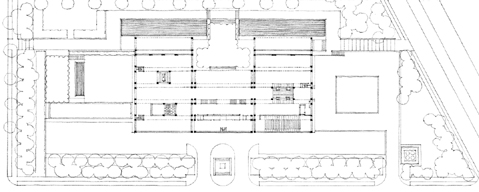

CLUSTERED ORGANIZATIONS

A clustered organization relies on physical proximity to relate its spaces to one another. It often consists of repetitive, cellular spaces that have similar functions and share a common visual trait such as shape or orientation. A clustered organization can also accept within its composition spaces that are dissimilar in size, form, and function, but related to one another by proximity or a visual ordering device such as symmetry or an axis. Because its pattern does not originate from a rigid geometrical concept, the form of a clustered organization is flexible and can accept growth and change readily without affecting its character.

Clustered spaces can be organized about a point of entry into a building or along the path of movement through it. The spaces can also be clustered about a large defined field or volume of space. This pattern is similar to that of a centralized organization, but it lacks the latter’s compactness and geometrical regularity. The spaces of a clustered organization can also be contained within a defined field or volume of space.

Since there is no inherent place of importance within the pattern of a clustered organization, the significance of a space must be articulated by its size, form, or orientation within the pattern.

Symmetry or an axial condition can be used to strengthen and unify portions of a clustered organization and help articulate the importance of a space or group of spaces within the organization.

Spaces organized by geometry

Nuraghe at Palmavera, Sardinia, typical of the ancient stone towers of the Nuraghic culture, 18th–16th century B.C.

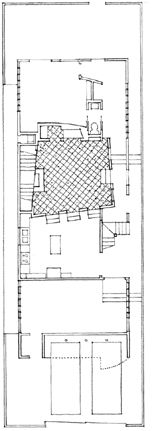

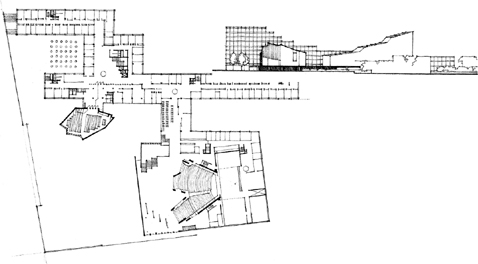

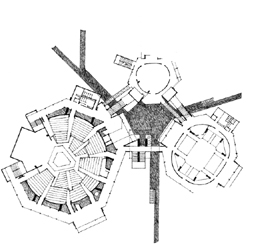

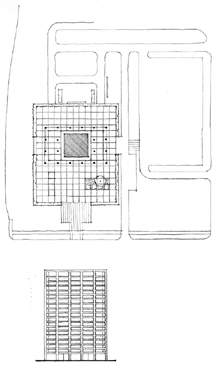

Meeting House, Salk Institute of Biological Studies (Project), La Jolla, California, 1959–65, Louis Kahn