Make no mistake, those who write long books have nothing to say.

Of course those who write short books have even less to say.

—Mark Z. Danielewski

THE TEXT is about nothing—always about nothing. Nothing is what keeps the text in play by rendering it irreducibly open and in/finitely complex. The nothingness haunting the text marks its border by exceeding it. This excess is the siteless site where difference endlessly emerges. The void that empties everything of itself is the incomprehensible gift that never stops giving. Art figures the unfigurable by giving what cannot be taken.

O O O

Today’s students live online and in the cloud. Far from a mere tool they occasionally utilize, the Web is a space they inhabit and that inhabits them. This house in which they dwell does not, however, always feel like a home because familiarity with technology does not erase the strangeness of the domain into which we are migrating. As Myspace becomes Ourspace, it’s a safe bet that in the twenty-first century, the virtual will increasingly displace, which is not to say replace, places and things that once seemed real. As virtual relations are becoming as important or even more important than real relations, real relations inevitably become entangled in virtual connections that both complicate and enrich them. Neither Leibe nor Arbeit remains the same in a wired world. The webs in which we are evermore entangled are not merely computer networks but are also global financial, media, and information networks. These changes are far from superficial; as we become inseparably joined to these prostheses by feedback loops, our very being is transformed. Young people, who are already living this future, are wired differently from previous generations. If one is patient enough to listen, though most adults are not, it quickly becomes clear that they do not see or think like their parents. The point is not that they think different ideas but that they actually think differently. The common complaint about students not reading enough is misguided; they read—perhaps not always as much as their parents and professors think they should—but they do not read the way their parents and teachers read. Their texts, which are not only verbal but more often are visual, auditory, and multimedia, have, like the contemporary world, lost their coherence and, thus, display little narrative continuity. As word gives way to image, old protocols no longer work, yet new logics have not been adequately formulated. Critics who insist it has ever been thus are wrong—something fundamental or, more precisely, nonfundamental is shifting, and this shift poses serious intellectual and pedagogical challenges.

How can the apparent gap between students who are wired differently and teachers who want to introduce them to the influential works in art, literature, philosophy, and religion be bridged? Do Hegel, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Melville, Poe, Stevens, Heidegger, and Derrida have anything to say to multitasking kids plugged into iPods, iPads, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and World of Warcraft? Conversely, do the children of network culture have anything to teach older generations about the ghosts who continue to haunt them—or at least some of them?

For the past twenty years, I have been attempting to bring together theory and practice by deploying a range of new technologies in my teaching. The consistent aim of these efforts has been to practice theory and theorize practice. These experiments require redrawing the traditional line separating teacher and students. The students and I have entered into a contract in which I pledge to teach them how my world can illuminate theirs and they promise to teach me how their world can reveal new aspects of mine. Every iteration of my courses has been different: Imagologies, Electronic Frontier, Cyberscapes, Networking, Real Fakes… In the early 1990s, I began experimenting by using teleconferencing technology to create a global classroom, with sites as distant as Helsinki and Melbourne. This led to efforts to webcast classes first locally and then globally through the Global Education Network (www.GEN.com).1 While this strategy effectively blew away classroom walls that once seemed impermeable, it did not fundamentally change what went on in the classroom. The seminar table had been expanded, but the texts discussed around it too often remained the same. To create the possibility of thinking, reading, and writing differently, I decided to develop courses in which students would be required to take a lab where they developed the skills necessary for working with multimedia. Since I do not know these technologies as well as the students, I have asked them to design and teach the labs. Instead of writing term papers, members of the class are required to produce an analytic and critical treatment of the issues we consider in the course in the form of a multimedia format. With the increasing sophistication of software and expanding bandwidth, it is now possible to distribute this material on the Web.

A recent version of this ongoing experiment was called Real Fakes. The following is the catalog description of the course:

Cloning, genetic engineering, transplants, implants, cosmetic surgery, artificial life, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, faux fashion, sampling, art about art, photographs of photographs, films about films, identity theft, derivatives, facial transplants, Enron, virtual reality, reality TV: the line long separating fake/real, artificial/natural, illusory/true, and inauthentic/authentic has disappeared. Fascination with the fake is as old as the imagination itself. But the shift from mechanical to digital and electronic means of production and reproduction has taken simulation to another level. What are the aesthetic, philosophical, social, ethical, and political implications of the multifaceted disappearance of the real? In addition to readings and discussions, there will be visits by a detective, a journalist, and experts on art forgery and counterfeiting.

Students were required to read theoretical texts such as Kierkegaard’s “Shadowgraphs: A Psychological Pastime,” Benjamin’s Arcades Project, Baudrillard’s “Simulacra and Simulations,” Eco’s Travels in Hyperreality, Foucault’s This Is Not a Pipe, and Derrida’s “‘Counterfeit Money’” and explore the work of artists such as P. T. Barnum, Tom Stoppard, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, J. S. G. Boggs, David Wilson, and Jeff Koons. In addition to participating in class discussions, students had to contribute to the construction of a website (www.realfakes.org), which was a knockoff of the National Enquirer’s home page. Course and site combined to create an extended text that was open and constantly changing in unexpected ways. This course expressed my abiding conviction that teaching and research are not only complementary but essential to each other: research without teaching is empty; teaching without research is blind. The multiple dimensions of different versions of this course formed part of an ongoing research project that continues to transform my thinking and writing.

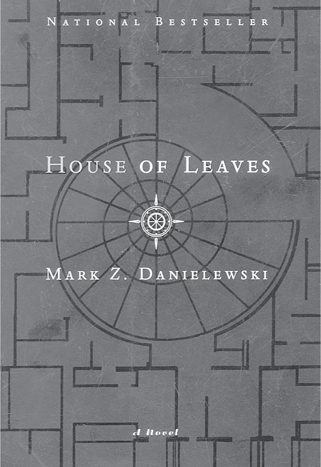

There are books I teach because I understand them and believe students should know what they have to offer, and there are books I teach because I do not understand them and know I can come to terms with them only with the help of students. After considerable deliberation, I decided to conclude Real Fakes with Mark Danielewski’s remarkable House of Leaves, a 709-page book that eludes every established genre. Though a work of fiction, it is not quite a novel. Who, after all, has ever heard of a novel that includes its own commentary and analysis, as well as appendices, illustrations, footnotes, and even a thirty-two-page index that is unlike any index you have ever seen? From the cover design to the last page, House of Leaves is a labyrinthine work of enormous complexity. One of the reasons I selected this unusual book was that it is as sophisticated an examination of the problem of the real and the fake or the original and the counterfeit in the age of electronic reproduction as any theoretical work I know. House of Leaves is something like The Recognitions for the digital age. This theme is actually identified in the first paragraph of the first chapter of the book:

While enthusiasts and detractors will continue to empty entire dictionaries attempting to describe or deride it, “authenticity” still remains the word most likely to stir a debate. In fact, this leading obsession—to validate or invalidate the reels and tapes—invariably brings up a collateral and more general concern: whether or not, with the advent of digital technology, image has forsaken its once unimpeachable hold on the truth.2

How Danielewski writes is as intriguing as what he writes. Freely mixing high and low culture, he weaves together literary theory, architectural theory, film theory, philosophy, theology, psychoanalysis, modern and postmodern art and literature, detective fiction, and punk rock to create a book that baffles as much as it dazzles. The complexity of the work is compounded by a graphic design that enacts or performs the ideas the multiple authors and characters explore. House of Leaves is as hypertextual as a printed book can possibly be: its multiple layers fold into one another to form a work that places unusual demands on readers.

The length and complexity of House of Leaves made me hesitant to assign it to undergraduates and lifetime learners. But I was intrigued by the work and wanted to experiment with it. As I prepared for the first class, I had no idea what to expect, so I decided to begin the discussion by asking them what they thought of the book. Predictably, the adults in the class threw up their hands and declared they were unable to make any sense of it, but the reaction of the students was completely unexpected. Far from being daunted, they were completely absorbed by the text. In almost four decades of teaching, I have never been so surprised by the response to a book I had assigned. It was as if the students had been waiting to read this book their whole lives. House of Leaves might not have been their home, but it is where the youth of network culture live at some level, and the students in Real Fakes knew it.3

At the most superficial level, House of Leaves is about a documentary film entitled The Navidson Record, which might or might not have been made. With their marriage in shambles, the Pulitzer Prize–winning photojournalist Will Navidson, his partner Karen Green, and their two children Chad and Daisy retreat from the city to a seemingly cozy house on Ash Tree Lane in a quiet Virginia suburb to repair their disintegrating family. But everything goes awry when the house turns out to be haunted. Returning from a wedding in Seattle, they sense “something in the house had changed. Though they had only been away for four days, the change was enormous. It was not, however, obvious—like for instance a fire, a robbery, or an act of vandalism. Quite the contrary, the horror was atypical. No one could deny there had been an intrusion, but it was so odd that no one knew how to respond” (24). After carefully examining every nook and cranny, Navidson discovers that the house is, impossibly, one-quarter inch larger on the inside than it is on the outside. As the house continues to expand while appearing to remain unchanged, Navidson calls on his dope-smoking twin Tom and other friends and associates to help him explore the cavernous abyss opening in their midst. Rather than a prison to be escaped, this cave draws people in with the promise to reveal a secret that can never be revealed. Having committed his life to the truth of the image, the prize-winning photographer records all the explorations of his haunted house with a video camera and eventually produces The Navidson Record from this footage.

There are many autobiographical references to the contentious relation of Danielewski and his sister to their filmmaker father and influential mother throughout House of Leaves. The narrative quickly becomes impossibly convoluted until, in good modernist fashion, it folds back on itself and becomes a book about the book. The ever-shifting labyrinth the characters explore is, among many other things, the book Danielewski is writing. In good postmodernist fashion, the modernist fold is interrupted, and the self-referentiality of the work of art does not come full circle but reveals a gap that can be neither closed nor concealed even though it is never really revealed. In this house, nothing is certain—nothing is certain; indeed, questions begin before the first page of the work “proper.” What seems to be the first edition is listed as the second edition because the purportedly documentary film around which the book is constructed appears to be based on an earlier work. “The Navidson Record did not first appear as it does today. Nearly seven years ago what surfaced was ‘The Five and a Half Minute Hallway’—a five and a half minute optical illusion barely exceeding the abilities of any NYU film school graduate. The problem, of course, was the accompanying statement that claimed all of it was true” (4). Fact based on illusion yields fiction, and claims about the film raise questions about the book. In a manner reminiscent of The Recognitions, we discover counterfeits of counterfeits being passed off as the real thing.

But the puzzles are even more profound because it is not clear who has written House of Leaves. Though Danielewski’s name appears on the cover and the copyright page, the title page indicates that Zampanò is the author and Johnny Truant has contributed an introduction and extensive notes. To compound confusion, in real life (or is it RL?) Danielewski signs all his personal e-mails Z. Zampanò turns out to have been a blind recluse who wrote an extensive commentary on The Navidson Record. When Johnny Truant, whose name suggests that he is a Johnny-come-lately, and his friend Lude, whose real name is Harry, discover Zampanò’s body in his cryptlike apartment, Johnny inherits a monstrous trunk that contains pages and pages of the old man’s reflections on the film. The twenty-something-year-old kid, who intermittently works in a tattoo parlor and is in love with a hooker named Thumper, assumes the onerous responsibility of organizing Zampanò’s ramblings into something resembling a coherent narrative. Johnny appends notes explaining his editorial procedures and adding his own observations and reflections, which are so extensive that they eventually overwhelm Zampanò’s text. As his prose becomes more convoluted, it becomes clear that his recent breakup with his girlfriend Clara English has had a significant impact on his writing. The texts are initially distinguished by contrasting typefaces, but as the work unfolds and refolds the difference between them becomes increasingly obscure. In his confusing introduction to the work, Johnny goes so far as to cast doubt on Zampanò’s identity.

He called himself Zampanò. It was the name he put down on his apartment lease and on several other fragments I found. I never came across any sort of ID, whether a passport, license or other official document insinuating that yes, he was An-Actual-&-Accounted-For person.

Who knows where his name really came from. Maybe it’s authentic, maybe made up, maybe borrowed, a nom de plume or—my personal favorite—nom de guerre.

As if this were not enough, Johnny, if he can be trusted, confirms suspicions about Navidson and his film.

After all as I fast discovered, Zampanò’s entire project is about a film which doesn’t even exist. You can look, I have, but no matter how long you search you will never find The Navidson Record in theaters or video stores. Furthermore, most of what’s said by famous people has been made up. I tried contacting all of them. Those that took the time to respond told me they had never heard of Will Navidson let alone Zampanò.

A book about a nonexistent film that claims to be true is, in a certain sense, a book about nothing.

But if Zampanò did not write the text, who did? Perhaps Johnny. The more deeply immersed in his work he becomes, the more like Zampanò Johnny appears to be. However, since Zampanò dies before the tale begins, we only see him through Johnny’s eyes. Though casting doubt on Zampanò and Navidson, Johnny never claims to be the author of the work. Some commentators have suggested that the book was actually written by Johnny’s mother, who, after slipping into madness, is confined to the Three Attic Whalestoe Institute. Whether the mad woman is confined to the attic or is trapped in the belly of the whale, the figure of the absent mother haunts House of Leaves. We learn about the mother through her letters to Johnny, which are appended to the text. The letter from the director of the institute informing Johnny of the death of his mother indicates that her name was Pelafina Heather Lièvre. In the first sentence of the concluding paragraph of his letter, the director “misspells” her name. “Again we wish to extend our sympathies over the death of Ms. Livre [sic]” (643). While livre means book, Li(e)vre is a visual pun that betrays the lie at the heart of the book. In House of Leaves, no name is proper.

Nor are dates insignificant. The book “begins” and “ends” on Halloween. Johnny dates his introduction October 31, 1998, and when we last see Navidson, he is in Dorset, Vermont, filming “his costume clad children” in the local Halloween parade.

In those final shots, Navidson gives a wink to the genre his work will always resist but inevitably join. Halloween. Jack O’lanterns. Vampires, witches, and politicians. A whole slew of eight year old ghouls haunting the streets of Dorset, plundering its homes for apples and blackness forever closing in above them….

Navidson does not close with the caramel covered face of a Casper the friendly ghost. He ends instead on what he knows is true and always will be true. Letting the parade pass from sight, he focuses on the empty road beyond, a pale curve vanishing into the woods where nothing moves and a street lamp flickers on and off until at last it flickers out and darkness sweeps in like a hand.

December 25, 1996

…the empty road beyond… where nothing moves… and darkness sweeps in like a hand. The nothing figured in darkness is what The Navidson Record, which, of course, does not exist, is all about. Zampanò, who, Johnny informs us, is “blind as a bat,” “sees” the darkness Navidson struggles to film.

Zampanò writes constantly about seeing. What we see, how we see and what in turn we can’t see. Over and over again, in one form or another, he returns to the subject of light, space, shape, line, color, focus, tone, contrast, movement, rhythm, perspective, and composition. None of which is surprising considering Zampanò’s piece centers on a documentary called The Navidson Record made by a Pulitzer Prize–winning photojournalist who must somehow capture the most difficult subject of all: the sight of darkness itself.

To film darkness would be to convey the insight blindness brings.

This book about the book layers text upon text. In addition to Navidson’s film, Zampanò’s commentary, and Johnny’s commentary on the commentary, House of Leaves includes an elaborate textual apparatus citing scholarly comments, articles, and books either about the text or relevant to it. Some are real and some are fake, and it remains unclear who has assembled these academic studies. It seems unlikely that the strung-out Johnny would be familiar with such works, but no obvious alternative is suggested. A prefatory note from the nameless editor warns the reader:

This novel is a work of fiction. Any references to real people, events, establishments, organizations or locales are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. Other names, characters and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, as are those fictionalized events and incidents which involve real persons and did not occur or are set in the future.

But this only complicates the puzzle because the author whose imagination has conjured other authors goes unnamed. Moreover, though many of the authors cited are real and the articles and books noted have actually been published, many of the passages quoted are made up, and pages referenced are either incorrect or do not exist. These textual plays have a theoretical purpose. Having studied at Yale during the halcyon days of deconstruction, Danielewski knows his literary theory inside out. Tucked away at the bottom of the blank page that follows the page where Navidson’s film runs out, the name of “the processing lab” is listed: “*Yale” (490).

Many of the readings of House of Leaves included in the notes are brilliant; indeed, they are worthy of publication in the best literary journals or with leading university presses. Every time the reader imagines a new way to interpret the text, he turns the page only to discover a footnote or a footnote to a footnote in which some “author” has anticipated his analysis. It is as if a precocious graduate student in literary theory had written a demanding work of fiction that includes every possible interpretation of it that might be proffered by the professors sitting on his doctoral committee. In a 2003 interview, Danielewski remarks: “I don’t mind admitting that I was extremely self-conscious about everything that went into House of Leaves. In fact—and I know this will sound like a very bold remark, but I will say it anyway since it remains the truth—I have yet to hear an interpretation of House of Leaves that I had not anticipated. I have yet to be surprised, but I’m hoping.”4 While the claim is hyperbolic, Danielewski’s ironic take on literary criticism is trenchant. In this book, the writer outsmarts critics who claim to be writers. And to make it all even sweeter, Danielewski knows it.

A commentary on an original that never existed, a commentary on that commentary, footnotes to books and articles analyzing the “novel,” exhibits, letters, poems, appendices, real and fake quotations, collages, index… Johnny characterizes Danielewski’s book when he describes Zampanò’s manuscript:

Endless snarls of words, sometimes twisting into meaning, sometimes into nothing at all, frequently breaking apart, always branching off into other pieces I’d come across later—on old napkins, the tattered edges of an envelope, once even on the back of a postage stamp; everything is anything but empty; each fragment completely covered with the creep of years and years of ink pronouncements; layered, crossed out, amended; handwritten, typed; legible, illegible; impenetrable, lucid; torn, stained, scotch taped; some bits crisp and clean, others faded, burnt or folded and refolded so many times the creases have obliterated whole passages of god knows what—sense? truth? deceit? a legacy of prophecy or lunacy or nothing of the kind?, and in the end achieving, designating, describing, recreating—find your own words; I have no more; or plenty more but why? and all to tell—what?

Nothing perhaps. Original or copy? Authentic or inauthentic? Primary or secondary? Genuine or counterfeit? Real or fake?

House of Leaves has multiple entrances but no exits. To enter this house is to wander through the underworld—Plato’s cave, Dante’s hell, Freud’s unconscious, Poe’s tomb, Melville’s whale, God’s house… tattoo parlors, bars, clubs, rave parties, rock-and-roll punk concerts, underground film theaters, strip joints, brothels, acid trips, crack houses, the Internet… In the absence of the original, beginning is difficult, and starts often seem false. Epigram upon epigram upon epigram: 1. “This is not for you”—which of course makes the book irresistible; 2. “Muss es sein?” which is the title of a work by Beethoven, though it sounds like a line lifted from Heidegger or perhaps even Lacan; 3. “I saw a film today, oh boy…”, which is supposed to be a line from an unnamed song by the Beatles. Can we take this book seriously? If so, how is it to be read, and how is it to be taught?

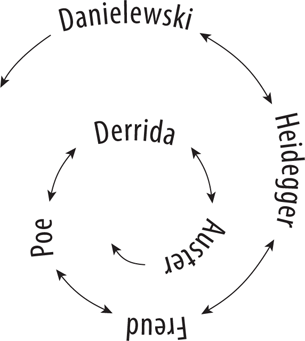

House of Leaves is a book about how to read in a world where the real, however it is figured, is always slipping away. Any effort to summarize the book, any attempt to say what the book is about, is bound to fail. The most that can be said is that the book is about the impossibility of saying what the book is about. How, then, can such a book be taught? After considerable reflection, I decided that the only way I could teach the book was by trying to show the students how to read it, by tracking a few of its tangled lines. Among the many threads we might have followed, I selected a particular series of connections, chain of associations, perhaps lines of filiation that held interest for me:

← Danielewski ↔ Heidegger ↔ Freud ↔ Poe ↔ Derrida ↔ Auster →

As I have noted, when Navidson and his family returned from Seattle, there had been an intrusion in the house so slight—a mere quarter inch—as to be virtually imperceptible. Nothing yet everything had changed. After describing Chad and Daisy running through the house “playing, giggling, completely oblivious to the deeper implications” of the intrusion, Zampanò shifts the narrative in a direction that initially seems incongruous. “What took place amounts to a strange spatial violation which has already been described in a number of ways—namely surprising, unsettling, disturbing but most of all uncanny. In German the word for ‘uncanny’ is ‘unheimlich’ which Heidegger in his book Sein und Zeit thought worthy of some consideration” (24). This observation is followed by a quotation in German from the section of Being and Time entitled “The Basic State-of-Mind of Anxiety as a Distinctive Way in which Dasein is Disclosed.” In a footnote, Johnny provides the English translation, which, he stresses, was “a real bitch to find.” He concludes that this text by “a former Nazi tweaking on who knows what… only goes to prove the existence of crack back in the early twentieth century. Certainly this geezer must have gotten hung up on a pretty wicked rock habit to start spouting such nonsense” (25).5 Initially this seems to be merely parody, but the more one reads the clearer it becomes that these musings must be taken seriously. By citing the passage in which Heidegger associates the unheimlich with the psychological experience of anxiety, Zampanò underscores the relationship between the house and the mind or, more precisely, the unconscious. Freud, of course, anticipated Heidegger’s account of the uncanny. He begins his famous essay “Das Unheimliche” by tracing the etymological implications of “uncanny” in several languages. As we have seen in the analysis of Plowing the Dark, the English term, Freud explains, suggests a haunted house: “English… Uncomfortable, uneasy, gloomy, dismal, uncanny, ghastly; (of a house) haunted; (of a man) a repulsive fellow.” After his long linguistic excursus, he concludes that the most satisfactory definition of unheimlich has been provided by Schelling: “‘Unheimlich’ is the name for everything that ought to have remained… secret and hidden but has come to light.” For Freud, this interplay of concealing and revealing suggests the female genitals, whose veiling and unveiling, he believes, lie at the heart of the experience of the uncanny. What most intrigues Freud about the notion of the uncanny, however, is its irreducible ambiguity. Commenting on the multiple nuances of the word, he writes:

What interests us most in this long extract is to find that among its different shades of meaning the word “heimlich” exhibits one which is identical with its opposite, “unheimlich.” What is heimlich thus comes to be unheimlich…. In general we are reminded that the word “heimlich” is not unambiguous, but belongs to two sets of ideas, which, without being contradictory, are yet very different: on the one hand, it means what is familiar and agreeable, and on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight.6

What is heimlich, thus, turns out to be unheimlich. And this is precisely what happens to the Navidson house.

In the passage from Being and Time that Zampanò cites, Heidegger interprets the uncanny as the experience of “not-being-at-home.” In contrast to “tranquilized self-assurance—‘Being-at-home,’” the uncanny unsettles in a way that leaves everything insecure. What makes the uncanny so disturbing is that it is provoked by nothing. “In anxiety,” Heidegger writes, “one feels uncanny. Here the peculiar indefiniteness of that which Dasein finds itself alongside in anxiety, comes proximally to expression: the ‘nothing and nowhere’” (25). As Kierkegaard first pointed out in The Concept of Anxiety (1844), anxiety, in contrast to fear, which always has a specific object, is a response to nothing, i.e., to no definite thing. The indefiniteness of this no-thing is precisely what makes anxiety so difficult to manage, control, and master. After all, how is it possible to cope with what is never present yet is not absent? For those who suffer anxiety, the experience is so unsettling that it is never again possible to be at home in the world. When understood in this way, anxiety is one of the names for “the unnamable horror” that haunts the house on Ash Tree Lane as well as House of Leaves.

It is Johnny Truant rather than Heidegger who brings the experience of anxiety to life. One afternoon, while working as an apprentice at the tattoo shop, Johnny suddenly has the strange feeling that “something’s really off. I’m off.” What makes this experience all the more unsettling is that “nothing has happened, absolutely nothing” (26). As he begins to have trouble breathing, Johnny is seized by the conviction that he has “caught sight of some tremendous beast crouched off in the shadows… beyond the point of reason.” But, he reports,

when I finally do turn, jerking around like the scared-shitless shit-for-brains I am, I discover only a deserted corridor, or what is merely a recently deserted corridor; this thing, whatever it had been, obviously beyond the grasp of my imagination or for that matter my emotions, having departed into alcoves of darkness, seeping into corners & floors, cracks & outlets, gone even to the walls. Lights now normal. The smell history. Though my fingers still tremble and I’ve yet to stop choking on large irregular gulps of air, as I keep spinning around like a stupid top spinning around on top of nothing, looking everywhere, even though there’s absolutely nothing, nothing anywhere.

The thing—the dreadful thing haunting Johnny is “absolutely nothing, nothing anywhere”—and everywhere. Neither present nor absent, this nothing is, in the words of a fictitious work of a critic Johnny cites later, “unpresent”7 but not precisely absent. How is this unpresent to be understood?

On June 6, 1950, Heidegger delivered a prescient lecture to the Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Kunst, which later was published under the title “The Thing.” Reflecting on “the abolition of distance” brought about by rapidly developing information technologies, he writes,

all distances in time and space are shrinking. Man now reaches overnight, by plane, places that formerly took weeks and months of travel. He now receives instant information, by radio, of events that he formerly learned about only years later, if at all…. The peak of this abolition of every possibility of remoteness is reached by television, which will soon pervade and dominate the whole machinery of communication.8

In the years since Heidegger wrote these words, the collapse of distance has accelerated, but nearness remains elusive, and people fall victim to the feeling of “helpless anxiety.” Trying to diagnose what occasions this anxiety, Heidegger reflects: “The terrifying is unsettling; it places everything outside its own nature. What is it that unsettles and thus terrifies? It shows itself and hides itself in the way in which everything presences, namely, in the fact that despite all overcoming of distances the nearness of things remains absent.” This absence continues to haunt a world drawn ever closer together by information and telecommunications technologies. But what is it?

To answer this question, Heidegger takes the unlikely example of a clay jug. The jug, he explains, is first and foremost a thing. But “what is a thing?” As always, the most basic questions turn out to be the most difficult. Instead of identifying the thing as an object (Gegen-stand or ob-ject) that stands over against or opposite a subject, Heidegger describes the thing as what “stands forth” or emerges. Then in a claim that is critical for understanding House of Leaves as well as all the texts it gathers together, he argues: “no representation of what is present, in the sense of what stands over against us as an object, ever reaches to the thing qua thing.” The thing, in other words, is unrepresentable and as such is never present, though it is not absent. As Johnny insists, “this thing” is “obviously beyond the grasp of [the] imagination.” To clarify his admittedly obscure analysis, Heidegger explains what it means for the jug to stand forth. After defining the jug by its function as a holding vessel, he proceeds to explain,

When we fill the jug with wine, do we pour the wine into the sides and bottom? At most, we pour the wine between the sides and over the bottom. Sides and bottom are, to be sure, what is impermeable in the vessel. But what is impermeable is not yet what does the holding. When we fill the jug, the pouring that fills it flows into the empty jug. The emptiness, the void is what does the vessel’s holding. The empty space, this nothing of the jug, is what the jug is as the holding vessel…. But if the holding is done by the jug’s void, then the potter who forms sides and bottom on his wheel does not, strictly speaking, make the jug. He only shapes the clay. No—he shapes the void. For it, in it, and out of it, he forms the clay into the form. From start to finish the potter takes hold of the impalpable void and brings it forth as the container in the shape of a containing vessel. The jug’s void determines all the handling in the process of making the vessel. The vessel’s thingness does not lie at all in the material of which it consists, but in the void that holds.

As we will see in more detail in the final chapter, the thing is nothing—the no-thing that allows the jug to stand forth or appear as the object we think we know. So understood, nothing is not the opposite of the thing; to the contrary, thing and nothing are inseparably interrelated—there can be no thing without nothing. For this reason, nothing haunts everything and, thus, is everywhere yet nowhere. What makes no-thing so strange is that it is a beyond that is not elsewhere but is the proximate betwixt ’n’ between that is always in a midst that is not our own.

The writerly equivalent of the relation between the void and the clay of the jug is the interplay between the white space of the blank page and the black ink of formed letters of the text. As speech emerges from silence, so writing emerges from a void that is never completely erased. Yet precisely this emptiness is what much—perhaps most—writing is designed to avoid. As Johnny explains, narratives are developed to make the world comprehensible, hospitable, habitable: “We create stories to protect ourselves” (20). But to protect ourselves from what? Above all else, stories are supposed to protect us from the emptiness, meaninglessness, absence, and the nothingness they nonetheless harbor. All such efforts, however, prove futile because nothing cannot be a-voided; there can be no story without the haunting emptiness it is written to fill. No matter how many stories there are, every house is haunted and every story is a ghost story.

As fits of anxiety deepen and panic approaches, Johnny frets: “I don’t know what I need but for no apparent reason, I’m going terribly south. Nothing has happened, absolutely nothing” (26). It is precisely because nothing has happened that Johnny is heading south. The farther south he journeys, the closer opposites become, until they collapse to create a concidentia oppositorum that is simultaneously destructive and creative. No one understood the unexpected terror of southern parts better than Edgar Allan Poe. Far from a verdant world of pleasure and leisure, the southern hemisphere is, for Poe, the region where warmth turns cold and life meets death. The two most memorable works in which Poe takes the reader to the bottomless bottom of the world are The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym and “MS. Found in a Bottle.” Poe, like many in his day, believed the South Pole was a vortex toward which all the waters of the world inevitably rush. As one approaches the pole, snow and ice create a blinding whiteout that turns everything dark. In “MS. Found in a Bottle,” an anonymous narrator sets out on a voyage to the archipelago of the Sunda Islands only to find himself, along with a nameless Swede, the victim of an horrific shipwreck. Impossibly, the narrator records the experience in a journal that survives the disaster: “Just before sinking within the turgid sea, its central fires suddenly went out, as if hurriedly extinguished by some unaccountable power. It was a dim, silver-like rim, alone, as it rushed down the unfathomable ocean.”9 When they surface, he reports, “we were enshrouded in pitch darkness, so that we could not have seen an object at twenty paces from the ship. Eternal night continued to envelop us.” Clinging to the wreckage, the two survivors drift in darkness until the Swede can no longer hang on and slips into “the abyss.” Left alone, the narrator sees or thinks he sees “a gigantic ship” bearing down on him. He miraculously escapes, boards the vessel, and records what he discovers: “I have made many observations upon the structure of the vessel. Although well armed, she is not, I think, a ship of war. Her rigging, build, and general equipment, all negative a supposition of this kind. What she is not, I can easily perceive; what she is, I fear it is impossible to say.” Like the distant deus absconditus, it is only possible to say what the ship is saying it is not. As the story unfolds, the narrator discovers that the ship is haunted. Members of the crew, speaking “a foreign tongue… glide to and fro like the ghosts of buried centuries.” With “the blackness of eternal night, and a chaos of foamless water” swirling, the ship is caught in a strong current and rushes “howling and shrieking by the white ice, thunders on to the southward with a velocity like the headlong dashing of a cataract.” The tale concludes,

To conceive the horror of my sensations is, I presume, utterly impossible; yet a curiosity to penetrate the mysteries of these awful regions, predominates even over my despair, and will reconcile me to the most hideous aspect of death. It is evident that we are hurrying onwards to some exciting knowledge—some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction. Perhaps this current leads us to the southern pole itself. It must be confessed that a supposition apparently so wild has every probability in its favor.

More fantastic than the tale itself is the “fact” that the narrator somehow manages to stuff his manuscript into a bottle and toss it into the sea at the very last moment.

After the disaster, the text surfaces from the abyss. This abyss is not merely the sea but is the unrepresentable void that makes the creation of the work of art possible. Like House of Leaves, “MS. Found in a Bottle” explores the unfathomable depths of the imagination and the intractable enigma of writing. Far from avoiding the void, writing, when it is not trivial, struggles to communicate the incommunicable by imparting “some never-to-be-imparted secret, whose attainment is destruction.” Writing sensu strictissimo is always what Maurice Blanchot calls “the writing of the disaster.”10

Danielewski or Johnny—it is never possible to be sure who the author is—rewrites “MS. Found in a Bottle” as the tale of the disaster of a ship named the Atrocity. The Swede becomes a Norwegian, and the South becomes the North Pole, but the story remains the same. When only eighteen, Johnny meets “an eccentric gay millionaire from Norway” who goes by the name Tex Geisa and delights in telling “weird sea stories” that always rush to the same inevitable ending. (Geisha-Tex is a community of artists fascinated by surface rather than depth or, perhaps, by the depths of surfaces. They are devoted to digital art, tattooing, skin art, body modification, wallpaper, and photography.). For Johnny, Tex is as weird as the tales he spins,

delivering one after another in his equally strange monotone, strangely reminiscent of something else, whirlpools, polar bears, storms and sinking ships, one sinking ship after another, in fact that was the conclusion to every single story he told so that we, his strange audience, learned not to wonder about the end but paid more attention to the inevitable rush of icy water, whirlpools and polar bears.

Tex’s tales remind Johnny of yet another story:

though not the same, a completely different story after all, built upon story after story, so many, how many? stories high, but building what? and why?—like for instance, why—the approaching “it” providing momentarily vague—did it have to leave Longyearbyen, Norway and head North in the dead of summer? Up there summer means day, a constant ebb of days flowing into more days, nothing but constant light washing over all that ice and water, creating strange ice blinks on the horizon, flashing out a code, a distress signal?—maybe; or some other prehistoric meaning?—maybe; or nothing at all?—also maybe; nothing’s all…

“Nothing’s all.” This is not the first time that Johnny has suspected that nothing’s all. But now the implications of his suspicion appear more far-reaching. Perhaps the nothing that is all is the never-to-be-imparted secret whose attainment is our destruction. If the secret is nothing, the distress signal would turn out to be a code that cannot be cracked. And if the code cannot be cracked, the message becomes unreadable, and unreadability becomes the message in the bottle.

With “wind whistling through the corridors like the voice of god,” the Atrocity, in spite of its size and experienced crew, sinks in the violent northern seas. Rushing to their watery graves, the sailors hear a monstrous

growl loose inside! their ship, tearing, slashing, hurling anyone aside who dares hesitate before it, bow before it, pray before it… breaking some, ripping apart others, burying all of them, and it’s still only water, gutting the inside, destroying the pumps, impotent things impossibly set against transporting outside that which has always waited outside but now on gaining entrance, on finding itself inside, has started to make an outside of the whole—there is no more inside…

When the outside is inside, nothing remains the same.

As horrible as this disaster is, there is, as Poe knew all too well, a worse fate: to be buried alive. Unbeknownst to most of the Atrocity’s crew members, the ship had two holds, “one secret, the other extremely flammable.” When the ship erupted in flames, one unnamed crewman sealed himself in the secret hold. But like the lines of a story, the walls of the compartment provide only temporary shelter: “in that second hold where one man hid, having sealed the doors, creating a momentary bit of inside, a place to live in, to breathe in, a man who survived the blast and the water and instead lived to feel another kind of death, a closing in of such impenetrable darkness, far blacker than any Haitian night or recounted murder” (299). The reprieve proves temporary because the sailor’s fate is sealed as tightly as his crypt. Like the manuscript in the bottle rising from the abyss, the sinking ship leaves traces to be deciphered on the surface of the sea:

slicing down into the blackness, vanishing in under twelve minutes from the midnight sun, so much sun and glistening light, sparking signals to the horizon, reminiscent of a message written once upon a time, a long, long time ago, though now no more, lost, or am I wrong again? never written at all, let alone before… unlawful hopes?… retroactive crimes?… unknowable rapes? an attempt to conceal the Hand at all, though I still know the message, I think, in all those blinks of light upon the ice, inferring something from what is not there or ever was to begin with, otherwise who’s left to catch the signs? crack the codes?

What hand has written these signs? Can they be caught? Can the code be cracked?

As the last moments of the entombed Norwegian’s life are recounted, the narrative indirectly confirms what we have suspected all along—the story of the Atrocity is Johnny’s as well as our own. Johnny cannot stay afloat because the outside is no longer outside but now is inside.

I’m losing any sense of who he was, no name, no history, only the awful panic he felt, universal to us all, as he sunk inside that thing [emphasis added], down into the unyielding waters, until peace finally did follow panic, a sad and mournful peace but somewhat pleasant after all, even though he lay there alone, chest heaving, yes, understanding home, understanding hope, and losing all of it, all long long gone a long long time ago…

This unnamable thing is the “terrifying and unsettling” nothing Heidegger names the uncanny. Sunk inside the thing that is sunk within oneself, every space that once seemed habitable now becomes unheimlich. If the something inferred turns out to be nothing, signs and codes remain opaque, and when signs are indecipherable and codes cannot be cracked, texts become labyrinths from which there is no exit.

A few pages—most of which are blank—after the end of the Atrocity narrative, a new chapter begins:

XIII

The Minotaur123

Alarga en la pradera una pausada

Sombra, pero ya el hecho de nombrarlo

Y de conjecturar su circunstancia

Lo hace ficción del arte y no criatura

Viviente de las que andan por la tierra.

—Jorge Luis Borges255

In note 255, the anonymous editor provides a translation of the Borges text: “… a slow shadow spreads across the prairie, / but still, the act of naming it, of guessing / what is its nature and its circumstances / creates a fiction, not a living creature, / not one of those who wander on earth.” Just as Poe’s effort to name the unnamable produces his tales, so, Borges suggests, the act of naming the shadow creates a fiction. Note 123 appears 203 pages earlier in a passage that, like the title, is sous rature.11 Footnotes to footnotes transform the text about the labyrinth into a labyrinth. In one note, Johnny explains that the crossed-out sections had been deleted by Zampanò. The passages Johnny restores summarize the story of the labyrinth Daedalus constructed as well as several interpretations of the myth. Some of the notes within notes refer to published books, others refer to fictitious authors and articles. The last line on the page on which this textual labyrinth is inscribed cites the influential essay “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” in which Derrida summarizes some of the most important aspects of his theory of textuality. Stressing the significance of “the question of structure and centrality,” Johnny, or whoever is providing these notes, quotes two passages in both French and English. Once again, the issue is the unthinkable outside that is inside systems and structures that are supposed to provide stability, purpose, and meaning.

The function of [a] center was not only to orient, balance, and organize the structure—one cannot in fact conceive of an unorganized structure—but above all to make sure that the organizing principle of the structure would limit what we might call the play of the structure. By orienting and organizing the coherence of the system, the center of a structure permits the play of its elements inside the total form. And even today the notion of a structure lacking any center represents the unthinkable itself…. This is why the classical thought concerning structure could say that the center is, paradoxically, within the structure and outside it. The center is at the center of the totality, and yet, since the center does not belong to the totality (is not part of the totality), the totality has its center elsewhere. The center is not the center.

Systems and structures include as a condition of their own possibility an excess that they cannot incorporate. The displacement of the center renders the text irreducibly open and thereby erases every bottom line.

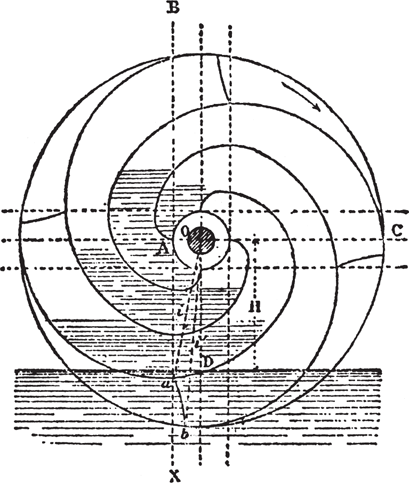

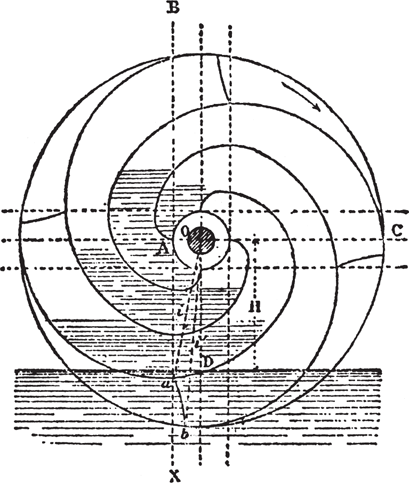

Though it is not readily apparent, this footnote is not the first time a Derridean trace appears in House of Leaves. The obscure black cover of the book bears the outline of a labyrinth whose center represents a variation of either Borges’s spiral staircase or the outline of a drawing in a footnote of Derrida’s essay “Tympan.” As the preface to Derrida’s collection of essays titled Margins of Philosophy, “Tympan” is, in effect, the margin of Margins. “Tympan” is important not only for the argument it presents but also for the design of the essay. Breaking with traditional monographic typography, Derrida divides the text into a wide column, devoted to a critical reassessment of Hegel’s philosophy, and a narrow marginal column that consists of a lengthy quotation from Michel Leiris’s Biffures. Biffure, it is important to note, means crossing out, canceling, erasure. The drawing Derrida reproduces is Lafaye’s Tympanum (1717).

“Tympanum” has multiple meanings—it is the membrane that forms the eardrum as well as the diaphragm of a telephone. In architecture, the tympanum is the recessed, ornamental panel enclosed by the cornices of a triangular pediment. A closely related word, tympan, refers in printing to a padding of paper or cloth placed over the plate of a printing press to provide support for the sheet being printed. A tympan is also the tightly stretched sheet or membrane that forms the head of a drum. Finally, in old French, tympaniser means to criticize or ridicule publicly.

Derrida begins his critique of Hegel by playing with all of these meanings of tympan and more.

To tympanize—philosophy.

Being at the limit: these words do not yet form a proposition, and even less a discourse. But there is enough in them, provided that one plays upon it, to engender almost all the sentences in this book.

Does philosophy answer this need? How is it to be understood? Philosophy? The need?12

3.1 Jacques Derrida, “Tympan.”

Source: Jacques Derrida, Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), xxi.

As in most of Derrida’s work, the proper name Hegel stands for Western philosophy as such. While the details of the argument need not concern us here, the conclusion is important. Philosophy, Derrida argues, presupposes yet cannot comprehend the limit or margin that constitutes it. In attempting to turn on itself to complete a circle of transparent self-reflexivity or self-referentiality, philosophy inevitably exposes the gap that can be neither bridged nor closed. By pushing philosophy to its logical conclusion, in the quest for Absolute Knowledge, Hegel unwittingly exposes philosophy to the limit it can never grasp. Instead of avoiding this margin or limit that philosophy cannot think, Derrida relentlessly probes it in all his writing.

The only explicit reference to “Tympan” in House of Leaves appears on page 401, where Zampanò cites this essay in an effort to “clarify” his association of Borges’s spiral staircase first with the shell (i.e., house) of a snail and then with quotations drawn from Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, which probes the psyche by exploring every nook and cranny of a house. Once again, footnotes proliferate; a note that provides Bachelard’s “original text” includes the reference to Derrida’s essay. After quoting Derrida’s text in French, Johnny adds:

In his own note buried within the already existing footnote, in this case not 5 but enlarged now to 9, Alan Bass (—Trans for Margins of Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981)) further illuminates the above by making the following comments here below:

“There is an elaborate play on the words limaçon and conquer here. Limaçon (aside from meaning snail) means spiral staircase and the spiral canal that is part of the inner ear. Conque means both conch and concha, the largest cavity of the external ear.”

386“Tympanum, Dionysianism, labyrinth, Ariadne’s thread. We are now traveling through (upright, walking, dancing), included and enveloped within it, never to emerge, the form of an ear constructed around a barrier, going round its inner walls, a city, therefore (labyrinth, semicircular canals—warning: the spiral walkways do not hold) circling around like a stairway winding around a lock, a dike (dam) stretched out toward the sea; closed in on itself and open to the sea’s path. Full and empty of its water, the anamnesis of the concha resonates alone on the beach.” As translated by Alan Bass.—Ed.

As Derrida folds into Danielewski who folds into Derrida, the reader becomes implicated in the text that now appears to be implicated in him. Inasmuch as the ear is a labyrinth, the labyrinth into which House of Leaves leads us is not merely outside but is inside as an outside we incorporate but cannot assimilate.

The typographical gestures of “Tympan” are neither incidental nor accidental but are integral to the argument of the essay. The tympan that Derrida traces in Margins cannot be directly represented in words or images but can be performed or enacted through strategies of textual design. The interplay of the columns as well as the blank or white space joining and separating them implies the elusive margin of difference that the text presupposes but cannot articulate. Originally published in 1972, “Tympan” is, in effect, the preliminary draft for a more extensive and demanding work that appears two years later. Glas is one of the most remarkable and challenging works in the history of philosophy (if that is what it is).13 Written before the era of word processing, it is a hypertext avant la lettre and, as such, is the prototype for House of Leaves.

While the connections are subtle, the lines joining House of Leaves and Glas unexpectedly pass through Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy.14 In the moments immediately after Navidson’s film runs out, Karen turns around “to discover the real emptiness waiting behind her.” Zampanò fabricates several critical interpretations of Karen’s experience, the most interesting of which refers to Paul Auster.

Karen’s action inspired Paul Auster to conjure up a short internal monologue tracing the directions of her thoughts.422

422 Paul Auster’s “Ribbons,” Glas Ohms, v. xiii, n. 83, August 11, 1993, p. 2.

(522)15

Danielewski plays on a suggestive slippage between Glas and glass in the passage. In French, glas means knell, passing-bell, tolling. The glas funèbre, which is very important for Derrida, is the death knell that sounds as the funeral procession passes the church. Danielewski includes two strategic references to Glas in an appended section entitled, significantly, “Bits.” A bit, of course, is, among other things, “a unit of information equivalent to the choice of either of two equally likely states of an information-carrying system” as well as a small piece or fragment. The fragments of Glas elude the binary logic of bits.

Incomplete. Syllables to describe a life. Any life.

I cannot even discuss Günter Nitschke or Norberg-Schulz. I merely wanted Glas (Paris: Editions Galilée, 1974). That is all. But the bastards reply it is unavailable. Swine. All of them. Swine. Swine. Swine.

Mr. Leavy, Jr. and of course Mr. Rand will have to do.16

April 22, 1991

Let us space.

Jacques Derrida

Glas

(654)

The association of Glas with the New York Trilogy is, in characteristic Austerian fashion, a matter of chance. The English translation of Derrida’s Truth in Painting mistranslates Glas as “glass,” thereby establishing an association with Auster’s New York Trilogy. Auster’s philosophical detective story consists of three volumes whose titles underscore their relevance for Danielewski’s work: City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room. The ghost of Poe haunts both Auster and Danielewski. City of Glass, which takes place on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in the neighborhood where Poe once lived is, among other things, a rewriting of “MS. in a Bottle” and The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. Danielewski, in turn, rewrites Auster’s rewriting of Poe in the Atrocity episode. The second hold of Danielewski’s sinking ship becomes “the locked room” in which the tolling of Glas echoes.

A final, seemingly insignificant detail. Who is Norberg-Schulz, and why does his name appear in the supplementary bit devoted to Glas? The dean of the Institute of Architecture at the University of Oslo, Christian Norberg-Schultz has developed a phenomenological approach to architecture that is deeply influenced by Heidegger’s philosophy. In his most important work, The Concept of Dwelling: On the Way to Figurative Architecture, Norberg-Schultz takes Heidegger’s essay “The Thing” as his point of departure for his analysis of dwelling.

What, then, are these things, which reveal their meaning through their configuration? Heidegger offers an answer in his famous essay, where he defines the thing as a “gathering of world.” He recalls that the original meaning of the word “thing” is “gathering,” and illustrates this significant fact with a phenomenological analysis of a jug. Then he goes on defining the world which is gathered by the thing as a “fourfold” of earth, sky, mortals and divinities, which belong together in a “mirror-play,” where “each of the four mirrors in its own way the essence of the others.” In other words, the things are what they are relative to the basic structure of the world. The things make the world appear and therefore condition man.17

What Norberg-Schulz overlooks is as important as what he considers. In his preoccupation with things, he fails to examine the thing and therefore does not explain why every dwelling is unheimlich. As I have stressed, Heidegger’s thing is the no-thing that obsesses Danielewski and haunts House of Leaves.

“Endless snarls of words, sometimes twisting into meaning, sometimes into nothing at all, frequently breaking apart, always branching into other pieces I’d come across later…” The connections, associations, filiations are endless, which is not to say infinite. Trace the connections of any name, date, episode, or reference, and you will become entangled in shifty connections that ceaselessly transform meaning as they multiply. In this way, the text becomes a labyrinth whose very openness leaves no exit. As we have discovered, however, this is no ordinary labyrinth because it has no center. A labyrinth without a center is a network, and, as Derrida insists, “even today the notion of a structure lacking any center represents the unthinkable itself.” The network, then, (impossibly) represents the unthinkable itself.

3.2 Mark Danielewski, cover, House of Leaves.

Source: Mark Danielewski, House of Leaves (New York: Random House, 2000).

The students patiently followed my philosophical and theoretical ramblings and absorbed as much as they could tolerate. But it was clear that they were anxious to get on to other issues. They understood intuitively what I came to see only gradually: House of Leaves is not merely a book but is actually a node in the World Wide Web, where more and more people live today. The book, in other words, is a web, and the Web is a house of leaves. The Web, after all, is exactly like a house that is bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. Screens are not terminals but are windows opening onto spaces that keep expanding faster and faster. Though he never explicitly associates the text with the Web, Danielewski leaves clues, which, once recognized, seem obvious. Most important, every time the word house appears in the text, it is printed in blue. Click “house,” and the tangled world of the Web opens. The more one explores House of Leaves, the clearer it becomes that the work exceeds the limits of the book—any book. The book turns out to be a printed interlude in a work that began and continues to emerge online. Instead of the usual publisher’s hype, the text on the jacket flap describes the actual history of the work.

Years ago, when House of Leaves was first being passed around, it was nothing more than a badly bundled heap of paper, parts of which would occasionally surface on the Internet. No one could have anticipated the small but devoted following this terrifying story would soon command. Starting with an odd assortment of marginalized youth… the book eventually made its way into the hands of older generations, who not only found themselves in those strangely arranged pages but also discovered a way back into the lives of their estranged children.

In House of Leaves, parents and teachers discover that the house they had thought was their own has been taken over by their kids and students.

Johnny weaves the history of the work into reflections recorded in a journal he keeps while he tries to regain a semblance of equilibrium by riding the rails with other homeless migrants across the country. Passing through Flagstaff, only a few miles from James Turrell’s Roden Crater, he jumps off the freight car and, while hanging out in a park, is drawn into a nearby bar by alluring music. While drinking cheap beer and talking with the locals, Johnny is startled to hear the band playing a song named “I Live at the End of a Five-and-a-Half-Minute Hallway,” which is the title of one of the most unsettling parts of The Navidson Record. Unable to believe his ears, he approaches the band and asks whether anybody has heard of a film with the same title. The response only deepens the mystery:

the drummer shook his head and explained that the lyrics were inspired by a book he’d found on the Internet quite some time ago. The guitar player walked over to the duffel bag lying behind one of their Vox amps. After digging around for a second he found what he was looking for.

“Take a look for yourself,” he said, handing me a big brick of tattered paper. “But be careful,” he added in a conspiratorial whisper. “It’ll change your life.”

Here’s what the title page said:

House of Leaves

by Zampanò

with introduction and

notes by Johnny Truant

Circle Round a Stone Publication

First Edition

As the conversation continues to unfold, it becomes clear that the band has not only read but is deeply involved with the book. Johnny reports that “they had discussed the footnotes, the names and even the encoded appearance of Thamyris on page 387, something I’d transcribed without ever detecting” (541). Unlike Danielewski, Johnny admits that he has neither completely understood what he has written nor has anticipated every response to “his” work. Seeming to mistake fiction for fact, the musicians say they often wonder what ever happened to Johnny. Though tempted to disclose his identity, Johnny finally decides to return the book with a simple thank you as he leaves the bar to continue his journey.

When one has “lost sense of what’s real and what’s not,” the line separating fact and fiction becomes obscure. Not only are facts often fictions, but fictions sometimes turn out to be fact. In fact, “5 and ½ Minute Hallway” was inspired by House of Leaves. Danielewski’s sister is a rock singer who performs under the stage name Poe. Her second CD, Haunted, includes the song “5 and ½ Minute Hallway,” which is an extended dialogue with House of Leaves. Lines of the book appear in songs on the CD, or lines of the song are reinscribed in the book—it is impossible to know which way these lines run. For all their differences, House of Leaves and Haunted are the “same” work. Brother writes and sister sings: “No-one should brave the underworld alone.” Poe’s voice echoes through Mark’s house, and Mark’s words echo in Poe’s songs.

By the time I introduced Poe into our class discussion, the students were already far ahead of me. They not only had discovered the complicated relationship between House of Leaves and Haunted but had immediately grasped its significance. Poe joined the roster of authors that already included Mark, Zampanò, Johnny, Navidson, and the countless writers and critics quoted and cited in notes. Like the members of the band in the Flagstaff bar, the students had become absorbed in the text. They were not reading the book as much as the book was reading them. When I realized what the book was doing to them, I asked them to post their responses to House of Leaves on one of the course websites. Several students reported that they had started listening to Poe’s music while reading the book.

When I first started reading this book, I was honestly bored. I was even reading it out in the sun.18 I don’t know when I was sucked in—but 6 hours later I finally put it down. Even after I put it down, I found myself thinking analytically about the text. (How often does that happen with an ordinary book?) I tried to figure out the names as anagrams in the margins of my textbooks. I got the Poe CD and listened to it… a lot. Especially when reading the book. (I think it’s even scarier than the book—for example, she puts a cut of her deceased father in.) I couldn’t fall asleep at night, wondering what the hell that labyrinth in the house meant (was it the world experienced by a blind person? Or the closet for everyone’s skeletons/repressed memories? When Navy compared the house to God, the homonym prey/pray popped into my mind). Crazy things like that.19

For student after student, reading the book actually became the haunting experience the “novel” describes.

I loved the way you get sucked into the book like the house sucks up everything that goes into it. Normally when I read a book, I read sections then take breaks to get a sense of my world back… yet Truant’s footnotes took over my sense of breaks as I experienced his life outside of Zampanò’s book. It was like an alternative reality that I kept relating to when I would carry on my life and reflect in my thoughts.20

As I pondered their posts and listened to what they said in class, I began to realize that they were actually living in House of Leaves, or, perhaps more accurately, they discovered that it was living in them.

Reading House of Leaves was more than just reading a book for class; it was an actual experience. At first, I was completely spooked out by hallways and Daisy’s “always,” but the more I read, the more I wanted to figure things out. I became Johnny Truant II. True to name, I actually skipped one of my classes because I was so engrossed by the story. Like Johnny, I tried to piece the clues together to make sense of it all. Even though I was not as obsessed, I still felt the need to pry and google everything that looked suspect. Of course, there were many frustrating dead ends, but that was part of the experience.21

The more they Googled, the more they felt the need to Google. The labyrinth of the book led to the labyrinth of the Web, which led back to the book until the two became seamless. Students discovered countless websites with thousands of posts investigating every clue, checking every reference, and tracking every association. As they searched and researched, the Web invaded the classroom until we were forced to admit that we were all in a room that was bigger on the inside than it was on the outside. Returning to House of Leaves from the Web, students had a deeper appreciation for the book’s graphic design. Though Danielewski stresses the influence of film on the design of the book, the work is actually more hypertextual than filmic. The twists and turns of the words on the page enact the convolutions of the text. One of the most insightful students in the class offered a telling account of his reading experience:

I do know, however, that my experience of reading the book mimics the experience of the characters as they are represented to me—Tom, Navy, Karen, Chad, Daisy, Reston, etc., but also Zampanò, Johnny, and even the “Editors,” so that my experience resonates on every different level, through and with all mediators, of the novel. That’s genius: Danielewski has constructed, in effect, a “choose your own adventure” that places readers at the center of the action without them consciously realizing it. By making me hunt for the location of footnotes or scour the web for clues to references or codes, or even by forcing me to physically turn the text upside down at times or to learn Morse code just to get the plot, Danielewski has brought the outside inside: my reading—not only my interpretation, but the actual physical process of my reading—is central to the story even though it cannot be contained by the book’s covers.22

As the book edged beyond its covers, we began to realize that both the class and the website we were building for Real Fakes were part of House of Leaves. In Danielewski’s world, which is, of course, our own, it is impossible to draw the line between original and copy, authentic and inauthentic, legitimate and illegitimate, real and fake.

As students continued to click and search, sign led to sign and reference to reference until exhilaration ended in frustration and we heard echoes of a detective singing: “all clues no solutions.” But matters were even more confusing because the students were no longer sure which clues were reliable and which were not. The discussion reached a turning point when one student took the class to the website for the Idiot’s Guide to House of Leaves (http://www.houselofleaves.4t.com/guide.html), where he had discovered the following post:

Depending on the version of House of Leaves you hold in front of you as you look at this page, several things could appear different to you. If you have a US hardcover edition of the novel, you’ll notice strange four character patterns covering the endpapers. Are those characters just there to make cool designs?

No, actually the characters are Hexidecimal [sic] code, when compiled in a hex editor and made into an AIFF file, the code actually plays as Mark Z. Danielewski’s sister Poe singing “Johnny, Angry, Johnny” in a 2 second clip from her track “Angry Johnny” from the album release “Hello.”23

Codes within codes within codes until nothing is decipherable and, thus, nothing remains certain—undeniably certain. Passages, of course, exist in books as well as houses. Are these passages credible or incredible? Where do they begin and where do they end? Without the key, how can any room be unlocked? How can the meaning of any work be decided? Are the codes by which we read and live discovered or invented? Real or fake? Can Melville’s Confidence-Man provide a “counterfeit detector” for this book? Where is the line between credibility and credulity? Suspicions aroused, students turned to a passage I had resisted pointing out: “Unfortunately, the anfractuosity of some labyrinths may actually prohibit a permanent solution. More confounding still, its complexity may exceed the imagination of even the designer. Therefore anyone lost within must recognize that no one, not even a god or an Other, comprehends the entire maze and therefore there can never be a definitive answer” (115).

Perhaps, then, House of Leaves—like life itself—is an elaborate confidence game. We cannot be certain. This is the point to which Danielewski leads the reader, and this is the point to which I had been steadily leading the class. Only when they realized that every house is always haunted by uncertainty were they ready to face the most unexpected and unsettling question of all: God.

Poe is haunted by her father. Her CD begins with her mother’s voice on an answering machine and Poe’s uncanny singsong words announcing the death of the father.

Mother’s answering machine: Hello, nobody’s home. Leave a message after the beep and somebody will get back to you.

Daughter: I thought you should know

Daddy died today

He closed his eyes and left here

At 12:03

He sends his love

He wanted you to know

He isn’t holding a grudge

And if you are you should let go

Pick up, pick up please, mom? hello?

Failing to connect, the daughter hangs up, and Poe begins to sing.

Ba da pa pa ba da pa pa…

Come here

Pretty please

Can you tell me where I am

You won’t you say something

I need to get my bearings

I’m lost

And the shadows keep on changing

And I’m haunted…

Throughout the CD, Poe’s songs are interrupted by the father’s voice echoing from beyond the grave. The liner notes, which include pictures of her father and mother as well as a photograph of her father’s obituary, begin with a dedication and explanation:

This album is dedicated to my father Tad Z. Danielewski (1921–1993)

A few years after my father died my brother and I came across a box of cassettes—recordings of my father’s voice. One was a letter to my brother that he had spoken into a tape recorder long ago: another was the recording of a speech he had given during his years as a teacher: a few more contained random recordings of forgotten family noise. Hearing his voice again shook me to my foundation. At first I couldn’t bear to listen to him, then I couldn’t stop. Finally I began sampling him. It was an eerie process. Had I resurrected a ghost? In some ways I had. Ultimately I entered into a dialogue with the ghost. Pieces of that dialogue compose the story contained in this album.

Tad  , once again

, once again  , Danielewski had been a filmmaker who spent years working on a documentary film entitled Spain: Open Door, which the Spanish government eventually confiscated because it included material the authorities deemed unacceptable. Though rumors about it being stored in hidden vaults persisted, the complete film was never recovered. The relation of House of Leaves and Haunted to Spain: Open Door is the mirror image of the relation of Zampanò’s screenplay and Johnny’s commentary/diary to The Navidson Record. The hallways of the house are the webs of the mind where the ghost of papa roams.

, Danielewski had been a filmmaker who spent years working on a documentary film entitled Spain: Open Door, which the Spanish government eventually confiscated because it included material the authorities deemed unacceptable. Though rumors about it being stored in hidden vaults persisted, the complete film was never recovered. The relation of House of Leaves and Haunted to Spain: Open Door is the mirror image of the relation of Zampanò’s screenplay and Johnny’s commentary/diary to The Navidson Record. The hallways of the house are the webs of the mind where the ghost of papa roams.

And I’m haunted

By the lives that I have loved

And actions I have hated

I’m haunted

By the promises I’ve made

And others I have broken

I’m haunted

By the lives that wove the web

Inside my haunted head

Hallways… always

I’ll always want you

I’ll always need you

I’ll always love you

And I will always miss you

Ba da pa pa ba da pa pa…

But papa never returns, and because of his nonarrival, Poe must sing, and Mark—which Mark?—must write.

Between “Terrified Heart” and “5 and ½ Minute Hallway,” Poe’s singing is interrupted by the recorded voice of the dead father: “Communication is not just words; communication is architecture. Because of course it is quite obvious that a house which would be built without the sense… without that desire for communication, would not look the way your house looks today!” Nor would a house look the way ordinary houses look if the architect wanted to communicate the incommunicable. Rather, the house would look something like House of Leaves.

A few pages after the excursus on the myth of the labyrinth, which includes Derrida’s claim that “today the notion of a structure lacking any center represents the unthinkable itself,” Exploration #4 is interrupted by a long reflection on the architecture of the house. Citing a fictitious work by Sebastiano Pérouse de Montclos (Palladian Grammar and Metaphysical Appropriations: Navidson’s Villa Malcontenta [Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1996]), Zampanò (or whoever is the author of this section) stresses that while there is general agreement that the labyrinth is a house, there is no consensus about who the occupant of the house might be. At this point, the narrative takes an unexpected turn.

Therefore the question soon arises whether or not it is someone’s house. Though if so whose? Whose was it or even whose is it? Thus giving voice to another suspicion: could the owner still be there? Questions which echo the snippet of gospel Navidson alludes to in his letter to Karen—St. John, chapter 14—where Jesus says:

In my Father’s house are many rooms: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you…

Something to be taken literally as well as ironically.

To name House of Leaves the Father’s house makes it no less uncanny. Two pages before this biblical reference, an extended footnote to the following passage begins in a window framed in blue. “This desire for exteriority is no doubt further amplified by the utter blankness found within. Nothing there provides a reason to linger. In part because not one object, let alone fixture or other manner of finish [sic] work has ever been discovered there.144” Nothing provides a reason to linger, and the longer we linger the stranger nothing becomes.

The windows in which footnote 144 appears are framed in blue and run for twenty-five pages. In a manner reminiscent of negative theology, the house is defined by what it is not: “Not only are there no hot-air registers, return vents, or radiators, cast iron, or other, or cooling systems…” Far from transparent, these Windows are filled with words, and the list in every window is repeated in reverse on the following page.