CONCLUDING UNSCIENTIFIC POSTSCRIPT

IN 1946, Paul Tillich published a seminal essay entitled “The Two Types of Philosophy of Religion,” in which he maintained that every philosophy of religion developed in the Christian tradition takes one of two forms. While Alfred North Whitehead once suggested that everyone is born either a Platonist or an Aristotelian, Tillich argues that every philosophy of religion is either Augustinian or Thomistic: the former he labels the ontological type, the latter the cosmological type. The distinction between the two types of the philosophy of religion is based on the differences between the two classical arguments for the existence of God, i.e., the ontological and cosmological arguments, which, though present since the Middle Ages, were particularly influential during the modern period. Tillich regards the teleological argument, or the argument from design, as a variation of the cosmological argument, which argues from effect (i.e., the world or its design) to cause (i.e., God as creator, governor and designer). The essay opens with a description of the most important differences between the two types.

One can distinguish two ways of approaching God: the way of overcoming estrangement and the way of meeting a stranger. In the first way man discovers himself when he discovers God; he discovers something that is identical with himself although it transcends him infinitely, something from which he is estranged, but from which he never has been and never can be separated. In the second way, man meets a stranger when he meets God. The meeting is accidental. Essentially they do not belong to each other.1

Since Tillich’s concern is the philosophy of religion, he focuses on the problem of the knowledge of God. In the ontological type, “the knowledge of God and the knowledge of Truth are identical, and this knowledge is immediate or direct.” From this point of view, “God is the presupposition of the question of God” (13). One cannot ask about God if one does not already possess an implicit knowledge of God. This argument is obviously Platonic: knowledge of truth is the condition of the possibility of distinguishing between true and false and as such cannot be derived from experience. The ontological argument, Tillich maintains,

is the rational description of the relation of our mind to Being as such. Our mind implies principia per se nota, which have immediate evidence whenever they are noticed: the transcendentalia, esse, verum, bonum. They constitute the Absolute in which the difference between knowing and the known is not actual. This Absolute as the principle of Being has absolute certainty. It is a necessary thought because it is the presupposition of thought.

(15)

Tillich’s argument hinges on the identification of God and Being, or, in his own terms, the power of Being. In a move that has far-reaching consequences, he claims that in the ontological type, epistemology and ontology are inseparable. “The Augustinian tradition,” he confesses, “can rightly be called mystical, if mysticism is defined as the experience of the identity of subject and object in relation to Being itself” (14). If God is being or the power of Being, then everything that exists is, in some way, united with the divine. God, in other words, is immanent in self and world.

In the cosmological type, by contrast, the relation between the human and divine is mediated or indirect. God is not immanent but is transcendent to self and world. Since nothing is grounded in itself, everything that exists is a sign referring beyond itself first to other things and ultimately to the divine origin, which is the truth of all reality.

For Thomas all this follows from his sense-bound epistemology: “The human intellect cannot reach by natural virtue the divine substance, because, according to the way of the present life the cognition of our intellect starts with the senses.” From there we must ascend to God with the help of the category of causality. This is what the philosophy of religion can do, and can do fairly easily in cosmological terms. We can see that there must be pure actuality, since the movement from potentiality to actuality is dependent on actuality, so that an actuality, preceding every movement must exist.

(18)

In the cosmological type, knowledge of God is a posteriori rather than a priori; God or truth, therefore, is the conclusion instead of the presupposition of argumentation. Because God remains transcendent, human reason alone cannot reach the complete truth of the divine. At the limit of human understanding, faith must supplement reason.

In contrast to the ontological type in which God is Being as such, in the cosmological type, God is a being. While Tillich consistently associates the cosmological type of the philosophy of religion with Aquinas, he traces this decisive shift in the understanding of the divine to the medieval Scottish Catholic theologian John Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308).

The first step in this direction was taken by Duns Scotus, who asserted an insuperable gap between man as finite and God as the infinite being, and who derived from this separation that the cosmological arguments as demonstrations ex finito remain within the finite and cannot reach the infinite. They cannot transcend the idea of a self-moving, teleological universe…. The concept of being loses its ontological character; it is a word, covering the entirely different realms of the finite and the infinite. God ceases to be Being itself and becomes a particular being, who must be known, cognitione particulari. Ockham, the father of later nominalism, calls God a res singularissima.

(19)

Tillich leaves no doubt that his sympathies lie with the ontological type. Indeed, he goes so far as to argue that the cosmological type represents “a destructive cleavage” that establishes oppositions that inevitably lead to human estrangement. In this analysis, unity is not only primal but is always present beneath or behind every form of separation. “The ontological principle in the philosophy of religion,” he concludes, “may be stated in the following way: Man is immediately aware of something unconditional which is the prius of the separation and interaction of subject and object, theoretically as well as practically” (22). Though not immediately obvious in this essay, Tillich’s argument grows out of his appropriation of analyses previously developed by Schelling and Heidegger.

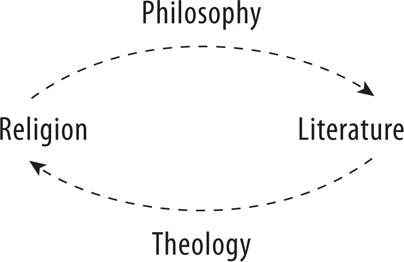

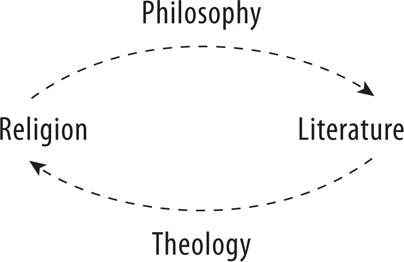

This insight suggests that Tillich’s analysis can be extended to illuminate contemporary philosophical and theological debates. The difference between the ontological and cosmological types roughly corresponds to the conventional distinction between continental and analytic philosophy, respectively. To see how this is so, it is necessary to take a detour through late medieval philosophical theology. Tillich’s passing reference to William of Ockham in the context of his discussion of Aquinas suggests an unexpected connection between medieval nominalism and modern analytic philosophy.

At first glance, no two thinkers seem more different than Aquinas and Ockham. While the former believes that God always acts rationally and, therefore, that the world is comprehensible, the latter insists that God is a deus absconditus and, thus, that knowledge is inescapably uncertain. Aquinas, however, distinguishes the natural and supernatural and, by extension, reason and faith. This distinction opens the way for Ockham’s theological innovation, which eventually led to the theological, philosophical, and sociopolitical revolution that in turn produced the Protestant Reformation.2 For Aquinas, faith and the supernatural supplement and complement but never contradict reason and nature. For Ockham, by contrast, the divine and the human as well as faith and reason are, in terms Kierkegaard would invoke centuries later, “infinitely and qualitatively different.”

According to Ockham, God is above all else omnipotent will—He is absolutely free and as such is bound by nothing, not even divine reason. God, in other words, is free to act in ways that sometimes seem arbitrary and often remain incomprehensible. Within this theological schema, the ground of the universe is the productive will of God, and existence is His unfathomable gift. This originary will is arational rather than irrational; as the condition of the possibility of reason as well as unreason, the divine will is finally unknowable. Faith, therefore, cannot be a matter of knowledge; indeed, one must believe in spite of not because of reason. If the universe (or the world) is the product of God’s creative will, unguided by the divine Logos, the order of things is contingent or perhaps even arbitrary. As Radically free, God can always undo what He has done, and thus there can be no final certainty or security in the world. In an effort to avoid this frightful prospect without forsaking his thoroughgoing voluntarism, Ockham distinguishes between God’s potentia absoluta (absolute power) and potentia ordinata (ordained power). While God has the absolute power to do anything that is not self-contradictory, He freely chooses to limit Himself by ordaining a particular order for the world. In different terms, divine will posits the codes by which the world is ordered and establishes the rules through which it operates. These codes and rules, however, are not themselves determined by any ascertainable code or rule. Every worldly structure, therefore, presupposes something it can neither include nor exclude. This voluntaristic ontology leads to an empirical epistemology—since whatever exists depends upon God’s free will, knowledge must be a posteriori and inductive rather than a priori and deductive. The only way to know anything about the world is to begin with sense experience. Such knowledge, however, always remains incomplete because it is ultimately “grounded” in the abyss of divine freedom. This Abgrund is neither simply immanent nor transcendent and, thus, is neither exactly present nor absent.

Ockham’s anthropology is the mirror image of his theology. Accordingly, his view of human beings is based on two fundamental tenets: first, the anteriority and priority of the singular individual over both social groups and the whole; and second, the freedom and responsibility of every individual subject. Ockham’s position on these issues leads to his most devastating critique of medieval theology and ecclesiology. The question over which he split with his predecessors is the seemingly inconsequential problem of the status of universal terms. For scholastic theology, the universal idea or essence is ontologically more real than individuals and epistemologically truer than particular empirical experiences. According to this doctrine, known as realism, humanity, for example, is essential, and individual human beings exist only by virtue of their “participation” in the antecedent universal form. Exercising his fabled razor, Ockham rejects realism and insists that universal terms are merely names, which are heuristic fictions useful for ordering the world and organizing experience but are not real in any ontological sense. This position eventually came to be known as nominalism (from nomen, Latin for “name”). For nominalists, only individuals are real. In the case of human beings, individuals are not constituted by any universal idea or atemporal essence but are formed historically through their own free decisions. The defining characteristics of human selfhood are individuality, freedom, and responsibility. According to nominalism, every whole, up to and including the human race, is nothing more than the sum of all the individuals that make it up.

Finally, Ockham’s nominalism entails a new understanding of language and, most important, of the relation between words and things. Though usually overlooked, there is a tension between Ockham’s empirical epistemology and his theology. On the one hand, language is intended to refer to and, therefore, represent specific entities, but, on the other hand, insofar as language is general, if not universal, and subjects as well as objects are singular, existing entities cannot be represented linguistically. Words and things fall apart, leaving us caught in a linguistic labyrinth from which there is no exit. In semiotic terms, signifiers, which appear to point to independent signifieds, actually refer to other signifiers. As linguistic beings, we traffic in signs, which, though appearing to refer to things, are actually signs of other signs. While seeming to represent the world, language is actually a play of signs unanchored by knowable referents. Words, then, are traces of what can never be represented and, as such, remain ghosts or phantoms of a real that has always already slipped away without becoming precisely absent.

Though the importance of his work is rarely acknowledged, many of the themes Ockham identified have been enormously influential throughout the Western tradition. Over the course of the following centuries, philosophers and theologians drew different and often conflicting conclusions from his guiding principles. In this context, it is important to stress that logical positivism and analytic philosophy, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, certain strands of continental philosophy both derive from Ockham’s nominalism. To trace relevant aspects of this genealogy, I will consider critical texts written by Martin Heidegger and Rudolf Carnap. This comparison creates the possibility of recasting Tillich’s two types of philosophy in different terms and thereby points toward a more promising alternative.

While the distinction between Anglo-American and continental philosophy is a recent invention, its roots lie buried in the late Middle Ages. Ockham wrote many of his most important treatises while at Oxford, and his influence continues even among those who do not realize it. His trenchant criticism of speculative theology and metaphysics, insistence on empirical verification of epistemological claims, and preoccupation with language left a deep impression on British and, by extension, American philosophy. The revival of Hegelianism and speculative philosophy in the United Kingdom during the early decades of the twentieth century triggered a critical response, which was largely responsible for creating a philosophical divide that has grown wider over the years. In an attempt to distinguish itself, analytic philosophy constituted continental philosophy as its own other and by so doing uncritically grouped philosophical positions that shared little more than their difference from positivistic and analytic philosophy—phenomenology, existentialism, neo-Thomism, hermeneutics, structuralism, deconstruction, and poststructuralism. Since geographical categories are ill suited to express philosophical and methodological differences, it is necessary to reformulate the terms in which philosophical debates have been cast for a century.

Instead of recycling the tired distinction between Anglo-American and continental philosophy, it is more helpful to contrast two styles of philosophizing: one that models itself on art and one that models itself on an interpretation of science that sets itself in opposition to art. This way of posing the issue is deliberately provocative because it suggests that there is nothing outside or beyond style. Furthermore, art and style are inseparable—there is no art without style and no style without art. It is, therefore, misleading to set up a hard and fast opposition between science and art. Just as there is a religious dimension to all culture, so there is an artistic dimension to all creative thinking, and just as religion is often most significant where it is least obvious, so style is often most influential where it remains unnoticed. The choice is not between style and nonstyle but between a style that represses its artistic and aesthetic facets and a style that expresses them stylistically. In order to explore the differences between these two alternatives and their far-reaching implications, I will examine the debate between two philosophers whose work has played a crucial role in framing the debate for almost a century: Rudolf Carnap and Martin Heidegger.3 Though Heidegger (1891–1976) and Carnap (1889–1970) were both German as well as contemporaries, they lived in completely different worlds. Heidegger was born into a Catholic family and never strayed far from his native Black Forest. After preparing for the priesthood as a youth, he went on to the University of Freiburg, where he wrote his Habilitation Schrift, entitled Duns Scotus’s Doctrine of Categories and Meaning. After the First World War, he returned to Freiburg and served as Husserl’s assistant until he eventually assumed his mentor’s chair. Over the years, Heidegger turned down many offers to move to more prestigious universities in order to remain at Freiburg and write in his beloved mountain hut in nearby Todnauberg. Carnap was born in Ronsdorf and grew up in Barmen. From 1910 through 1914, he also attended the University of Freiburg, where he studied philosophy, physics, and mathematics, and at Jena, where he took three courses with Gottlob Frege. Combining research in physics with his interest in Kant, he completed a dissertation, entitled simply Space (Der Raum), under Bruno Bauch in 1921. In 1926, Carnap was appointed an assistant professor at the University of Vienna and became increasingly involved in the Vienna Circle. With a flourishing artistic community, the burgeoning field of psychoanalysis, and its long history of musical innovation, Vienna was a thriving center of modernism during these years. After moving to Prague in 1931, Carnap was forced to flee Europe for the United States, where he taught at the University of Chicago from 1936 to 1952.

In 1929, Heidegger and Carnap published brief texts that proved decisive for later twentieth-century philosophy. Carnap and his colleagues Hans Hahn and Otto Neurath issued what is widely acknowledged as the manifesto of the Vienna Circle, “The Scientific Conception of the World: The Vienna Circle,” and Heidegger delivered his inaugural lecture at the University of Freiberg—“What Is Metaphysics?” Both Carnap and Heidegger called for the overcoming of metaphysics, but neither their reasons nor their intentions could have been more different. For Carnap, the abstractions and complexities of speculative metaphysics were vacuous as well as sociopolitically suspect. He insisted that clarity and simplicity are the necessary characteristics of truth. Philosophy can only enter the modern era by appropriating what he described as a scientific method of investigation and empirical procedures for verification. For Heidegger, by contrast, modern science and technology, which are the culmination of what he labels the Western “ontotheological tradition,” pose a threat to human life as well as the future of the planet. The only way to avert impending disaster is to develop a thoroughgoing critique of science and technology by recovering philosophy’s original relationship to art. Three years after Heidegger’s lecture, Carnap responded in an article entitled “The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language.” The significance of these two essays far surpasses the initial exchange that led to their publication. In them, Heidegger and Carnap present contrasting positions that implicitly and explicitly shaped philosophical debate for decades.

Heidegger approaches his questioning of metaphysics from an unexpected direction by discussing the role of science in shaping the modern university: “What happens to us, essentially, in the grounds of our existence, when science becomes our passion?”4 Far from a method of disinterested investigation capable of establishing objective truth, science, Heidegger maintains, is the product of the Western metaphysical tradition that has been characterized by the pernicious “forgetting of being.” He argues, “Today only the technical organization of universities and faculties consolidates this burgeoning multiplicity of disciplines; practical establishment of goals by each discipline provides the only meaningful source of unity. Nonetheless, the rootedness of the sciences in their essential ground has atrophied.”5 By historically contextualizing science in terms of broader sociocultural currents, Heidegger extends the arguments of his mentor, Husserl. In his influential essay “The Origin of Geometry,” which is appended to Crisis of the European Sciences, Husserl argues that even geometry, which is the “purest expression of the theoretical attitude,” is constituted in what he labels the Lebenswelt. The crisis to which his title alludes occurs when people forget that mathematical ideas and scientific concepts are embedded in everyday attitudes and practices. The task of philosophy or, in Husserl’s terms, phenomenology is to think what the tradition has left unthought through the phenomenological reduction, which exposes the originary constitution of every form of consciousness.

In his first book, Edmund Husserl’s Origin of Geometry; An Introduction, Derrida clarifies the point of Husserl’s analysis:

By a spiraling movement, which is the major find in our text, a bold clearing is brought about within the regional limits of the investigation and transgresses them toward a new form of radicality. Concerning the intentional history of a particular eidetic science, a sense-investigation of its contradictions of possibility will reveal to us exemplarily the conditions and sense of the historicity of science in general, then of universal historicity—the last horizon for all sense and Objectivity in general.6

Such critical reflection has important practical consequences because it “desedimentizes” tradition in a way that reactivates and revitalizes it. As we will see, there is a direct line from Husserl’s phenomenological reduction and desedimentation through Heidegger’s “de-structuring” (Destrucktion) or “dismantling” (Abbau) to Derrida’s deconstruction. For Heidegger, the “essential ground” that science forgets is being itself. Far from disinterested, science’s preoccupation with beings is an extension of Nietzsche’s will to power in “the will to mastery” through which “man” seeks to “secure to himself what is most properly his.” Within this scheme, the scientific attitude rests on two basic principles: representation and utilitarianism. In order to control the world, man must first objectify and then manipulate it. “This objectifying of whatever is,” Heidegger argues,

is accomplished in a setting-before, a representing, that aims at bringing each particular being before it in such a way that man who calculates can be sure, and that means be certain, of that being. We first arrive at science as research when and only when truth has been transformed into the certainty of representation. What it is to be is for the first time defined as the objectiveness of representing, and truth is first defined as the certainty of representing, in the metaphysics of Descartes.7

When truth collapses into certainty with Descartes’s turn to the subject, everything becomes a “standing-reserve” or resource programmed to serve human ends, and man finally seems to be at home in a world where everything is manageable. But at precisely this moment of apparent triumph, humankind’s fortunes are reversed.

As soon as what is unconcealed no longer concerns man even as an object, but does so, rather, exclusively as standing-reserve, and man in the midst of objectlessness is nothing, but the orderer of the standing-reserve, then he comes to the very brink of a precipitous fall; that is he comes to the point where he himself will have to be taken as standing-reserve. Meanwhile man, precisely as the one so threatened, exalts himself to the posture of lord of the earth. In this way the impression comes to prevail that everything man encounters exists only insofar as it is his construct. This illusion gives rise in turn to one final delusion: It seems as though man everywhere and always encounters only himself.8

In a manner reminiscent of Hegel’s analysis of the master-slave relationship in the Phenomenology of Spirit, the master affirms himself by negating the world around him. Through this unexpected reversal, the exercise of the will to power unleashes what Hegel, describing the reign of terror following the French Revolution, called “the fury of destruction,” which ultimately destroys the world and with it humanity.

The only way to turn back from the all-consuming abyss opened by modern science and technology, Heidegger argues, is to turn toward a no less disturbing abyss that is buried deep in the ever-receding past. He devotes his entire philosophical enterprise to questioning what science forgets, ignores, or even represses. He names this elusive remainder das Nichts—(the) nothing. While science is preoccupied solely with “beings and beyond that—nothing,” Heidegger asks, “What about this nothing?”

The nothing is rejected precisely by science, given up as a nullity. But when we give up the nothing in such a way don’t we just concede it? Can we, however, speak of concession when we concede nothing? But perhaps our confused talk already degenerates into an empty squabble over words. Against it science must now reassert its seriousness and soberness of mind, insisting that it is concerned solely with beings. The nothing—what else can it be for science but an outrage and a phantasm? If science is right, then only one thing is sure: science wishes to know nothing of the nothing.9

Heidegger is convinced that modern science and technology mark the closure, which is not the end, of the Western ontotheological tradition. Atomic and cybernetic technologies make explicit the destructive will to power that has always been implicit in metaphysics. The long march of history has been a pedagogy in forgetting whose trajectory cannot be reversed unless philosophy thinks what previously has been left unthought. From the naïve everyday perspective to the seemingly sophisticated point of view of science and mathematics, the unthought remainder, surplus, or excess, which is the condition of the possibility of thought as well as the impossibility of its completion, is nothing.

But what precisely “is” this nothing? The question, of course, negates itself in its very formulation. That is why Heidegger never asks it directly; rather, he asks indirectly, “How is it with nothing?” Nothing cannot be objectified, represented, or manipulated; it is never given yet always gives whatever is and is not. Nothing is apprehended, which is not to say comprehended, in moods like distraction, boredom, and above all anxiety. As we have seen, in contrast to fear, which always has a specific object, anxiety reveals nothing “in the slipping away of beings…. We ‘hover’ in anxiety. More precisely, anxiety leaves us hanging because it induces the slipping away of beings as a whole.”10 This void in the midst of whatever appears to be present renders all beings uncanny and undercuts the very possibility of complete knowledge and reasonable control. Where science sees causes that ground determinate entities, Heidegger glimpses the groundless ground—der Abgrund—from which everything emerges and to which all returns through a process he labels “nihilation.” In an important passage that Carnap discusses at length, Heidegger argues:

[Nihilation] is neither an annihilation of beings nor does it spring from a negation. Nihilation will not submit to calculation in terms of annihilation and negation. The nothing itself nihilates.

Nihilation is not some fortuitous incident. Rather, as the repelling gesture toward the retreating whole of beings, it discloses these beings in their full but heretofore concealed strangeness as what is radically other—with respect to the nothing.

In the clear night of the nothing of anxiety the original openness of beings as such arises: that there are beings—and not nothing. But this “and not nothing” we add in our talk is not some kind of appended clarification. Rather, it makes possible in advance the revelation of beings in general. The essence of the originally nihilating nothing lies in this, that it brings Da-sein for the first time before beings as such.11

From Heidegger’s point of view, the entities that science investigates and technology manipulates are neither self-contained nor self-grounded; to the contrary, they emerge from an elsewhere, which, while never present, is not absent. Nihilating nothing clears the space that allows differences to be articulated and identities to be established even if never secured. Truth, Heidegger maintains, does not involve the correspondence between word and thing, representation and fact, or signifier and signified; it is the primordial opening (Aletheia) between and among beings that is the condition of the possibility of all forms of correspondence. As such, truth can be neither represented nor comprehended but is revealed as the concealing that once was called the play of the gods and now is staged in the work of art.

With “seriousness and soberness of mind,” Carnap confidently declares all such speculation meaningless nonsense. The goal of the Vienna Circle was “to set philosophy upon the sure path to science.” In their 1929 manifesto, Carnap, Hahn, and Neurath declare:

It is the method of logical analysis that essentially distinguishes recent empiricism and positivism from the earlier version that was more biological-psychological in its orientation. If someone asserts “there is a God,” “the poetic and primary basis of the world is the unconscious,” “there is an entelechy which is the leading principle in the living organism,” we do not say to him: “what you say is false”; but we ask him: “what do you mean by these statements?” Then it appears that there is a sharp boundary between two kinds of statements. To one belong statements as they are made by empirical science; their meaning can be determined by logical analysis or, more precisely, through the simplest statements about the empirically given. The other statements, to which belong those cited above, reveal themselves as empty of meaning if one takes them in the way that metaphysicians intend.

Logical positivism rests on two fundamental principles: (1) the strict adherence to the scientific method, which entails a rigorous empiricism, and (2) the insistence that all problems can be solved by logical and linguistic analysis. Absolutely convinced of the validity of their method, Carnap and his colleagues go so far as to proclaim, “The scientific world-conception knows no unsolvable riddle.”12 For science and philosophy to reach the lofty goal of total knowledge, they must free themselves from theology and metaphysics by dismantling traditional ways of thinking through a critical analysis of the language.

Though the details of analysis differ, variations of this philosophical approach share five important assumptions, several of the most important of which can be traced to medieval nominalist theology.

1. Meaningful linguistic claims are cognitive. This is not to imply that language is deployed in no other ways. It can, for example, be used to express intentions and feelings. Meaning, however, can only be determined by logical analysis and “the reduction to the simplest statements about the empirically given.”

2. Meaningful statements are referential. They refer to actual entities, events, or states of affairs. A. J. Ayre points out that for logical positivists “the meaning of a proposition is its method of verification. The assumption behind this slogan is that everything that could be said at all could be expressed in terms of elementary statements. All statements of a higher order, including the most abstract scientific hypotheses, were in the end nothing more than shorthand descriptions of observable facts.” This verification requires “introspectible or sensory experiences.”13

3. Meaningful statements are representational. Words and statements represent objective facts to the cognitive subject.

4. Scientific and philosophical analysis presupposes logical/linguistic and ontological atomism. Statements are meaningful only insofar as “they say what would be said by affirming certain elementary statements and denying certain others, that is, only insofar as they give a true or false picture of the ultimate ‘atomic’ facts.”14

5. Rigorous analysis reduces complexity to simplicity.

Before exploring the importance of these principles for theology and metaphysics, it is necessary to consider some of their implications for the philosophical position they are supposed to support. In logical and ontological atomism, terms and entities are taken to be singular; their identity is prior to and independent of their relations to other terms and entities. Since the singular alone is real, the whole is nothing more than the sum of its parts and as such is epiphenomenal.15 Accordingly, this method of analysis privileges simplicity over complexity; more precisely, critical analysis always reduces complex structures and systems to their simple parts. For Carnap and those who share his faith, the task of philosophy at the end of metaphysics is largely negative. The application of scientific method to philosophical analysis “serves to eliminate meaningless words, meaningless pseudo-statements.”16 Any extension beyond critical and regulative analysis cannot be justified in terms of logical positivism’s foundational principles.

As we have seen, the principle of verification plays a critical role in logical positivism as well as in radical empiricism. But when critically assessed, it is clear that this style of empirical verification leads to insurmountable difficulties. As Ockham and his followers realized centuries earlier, if reality, subjective as well as objective, is singular, it can be neither linguistically mediated nor conceptually represented. The generality of language cannot capture the constitutive specificity of real entities, events, states of affairs, or other subjects. Furthermore, if the principle of verification rests upon “the subject’s introspectible or sensory experiences,” it can hardly be normative. Protests to the contrary notwithstanding, experience is idiosyncratic or, in terms that would shake but not subvert logical positivism and radical empiricism, “private.” Ayre correctly argues,

the most serious difficulty lay in the privacy of the objects to which the elementary statements were supposed to refer. If each one of us is bound to interpret any statement as being ultimately a description of his own private experiences, it is hard to see how we can ever communicate…. It was maintained by Carnap and others that the solipsism which seemed to be involved in this position was only methodological; but this was little more than an avowal of the purity of their intentions. It did nothing to mitigate the objections to their theory.17

Contrary to every expectation, “scientific philosophy” ends up in the same solipsistic impasse as Sartrean existentialism.

Carnap finally conceded this problem, but his attempted solution creates further difficulties for his position. “In the theory of knowledge it is customary to say that the primary sentences refer to ‘the given’; but there is no unanimity on the question of what it is that is given.” In an effort to overcome solipsism, he proposes intersubjective criteria for verification. Instead of being grounded in private experiences, which cannot be communicated, verifiable statements of scientific philosophy must refer to physical realities and events that are publicly intelligible. This shift from private to intersubjective experience leads to the reinterpretation of meaning in terms of syntax: “The syntax of the word must be fixed, i.e., the mode of its occurrence in the simplest sentence form in which it is capable of occurring; we call this sentence form its elementary sentence.” This revision leads to a further conclusion, which is decisive for his criticism of Heidegger: “Since the meaning of a word is determined by its criterion of application (in other words: by the relations of deductibility entered into by its elementary sentence-form, by its truth-conditions, by the method of verification), the stipulation of the criterion takes away one’s freedom to decide what one wishes to ‘mean’ by the word.”18

Carnap’s argument does not resolve the problems with his position. First, as long as he remains committed to logical and ontological atomism, intersubjective experience and knowledge remain impossible. He asserts the necessity for intersubjective criteria of verification but does not explain how they are possible. Second, even if it were possible to establish such criteria, intersubjectivity would undercut the very positivity and objectivity to which Carnap remains committed. By associating meaning with “protocols” that determine the criteria of application, he effectively identifies meaning with use and, by extension, with convention. Insofar as meaning is intersubjective, it is established by consensus and as such is socially constructed. Far from objective and, thus, independent of any particular interpretive framework, criteria for adjudicating meaning are internal to historically contingent linguistic practices. In other words, there are no metarules, or, in Kierkegaard’s terms, there is no Archimedean point with which to choose the rules by which we think and act. Protocols are not self-grounding but are constituted through originary decisions that can be neither explained nor justified in terms of the rules they institute. As Goethe and Freud insist, “in the beginning is the act.”

Carnap does not seem to have been fully aware of these problems and proceeded with what he confidently believed was a thoroughgoing dismantling of “the metaphysical and theological debris of millennia.”19 The claims of metaphysics and theology, he argues, are “pseudo-statements” that are “entirely meaningless.” As we have seen, a word is meaningless if no method of verification can be specified or if meaningful words are put together incorrectly. Since the word “God” refers to something beyond experience and is, therefore, “deliberately divested of its reference to a physical being or to a spiritual being that is immanent in the physical,” it is inescapably meaningless.20 Most of the other important terms used by metaphysicians and theologians, e.g., the Idea, the Absolute, the Unconditioned, the Infinite, essence, the I, etc., are similarly disqualified. In the second type of pseudostatement, meaningful words are combined in such a way that no meaning results. “The syntax of language,” Carnap argues, “specifies which combinations of words are admissible and which are inadmissible.”21 Even though the rules of grammar and syntax are not violated, no meaning is conveyed.

To support his argument, Carnap turns to what he describes as the “metaphysical school, which at present exerts the strongest influence in Germany.” He focuses on a few sentences from Heidegger’s essay “What Is Metaphysics?” which I have already considered. Since the translation of the text of Heidegger that Carnap cites differs from the one I used, it will be helpful to quote this important passage again.

What is to be investigated is being only and—nothing else; being alone and further—nothing; solely being, and beyond being—nothing. What about this Nothing?… Does the Nothing exist only because the Not, i.e., the Negation exists? Or is it the other way around? Do Negation and the Not exist only because the Nothing exists?… We assert: the Nothing is prior to the Not and the Negation…. Where do we seek the Nothing? How do we find the Nothing…. We know the Nothing…. Anxiety reveals the Nothing…. That for which and because of which we are anxious was “really”—nothing. Indeed: the Nothing itself—as such—was present…. What about this nothing?—The Nothing itself nothings.22

Heidegger’s argument fails Carnap’s test for meaning on two counts. First, his claims obviously do not refer to physical entities or actual events and, therefore, cannot be empirically verified. Given Carnap’s criteria, every statement about nothing is necessarily a pseudostatement. But Heidegger’s argument also fails the syntactic test—he violates linguistic conventions by using “the same grammatical form for meaning and meaningless word sequences.” Carnap concentrates his criticisms on two sentences: “The Nothing nothings” and “The nothing only exists because…” In the first sentence, Heidegger makes two mistakes: first, he uses the word “nothing” as a noun, when “it is customary in ordinary language to use it in this form in order to construct a negative existential sentence,” and second, he makes up a meaningless verb “to nothing” (in the previous translation, “to nihilate”). Far worse than attempting to extend the meaning through metaphorical use, Heidegger creates a new word that has no meaning. The second sentence, Carnap insists, is simply self-contradictory—to say that nothing exists—regardless of how this is understood—is nonsensical.

If Carnap is right, then why do so many seemingly intelligent people cling to their metaphysical and theological commitments? Such assertions, Carnap tentatively suggests, “serve for the expression of the general attitude of a person towards life (Lebenseinstellung, Lebensgefühl).” Suspending his usual criteria for judgment, he allows himself to speculate, “Perhaps we may assume that they originated from mythology…. The heritage of mythology is bequeathed on the one hand to poetry, which produces and intensifies the effects of mythology on life in a deliberate way; on the other hand, it is handed down to theology, which develops mythology into a system.”23 Following Freud, with whom he shares nothing else, Carnap insists that theologians and metaphysicians differ from artists in one important way: they believe in the reality of their fantasies. Such beliefs, he insists, pose a threat not only to scientific philosophy but to modernity itself.

While claiming that philosophy is always in the service of science, the agenda of Carnap and his colleagues is considerably more ambitious. They conclude “The Scientific Conception of the World” with a resounding declaration that echoes other modernist manifestos of the time: “We witness the spirit of the scientific world-conception penetrating in growing measure the forms of personal and public life, in education, upbringing, architecture, and the shaping of economic and social life according to rational principles. The scientific world-conception serves life, and life receives it.”24 Above and beyond securing scientific knowledge, philosophy prepares the way for nothing less than the transformation of the world. In making such bold claims, Carnap echoed the ambitions of many modern artists.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, Vienna was a hotbed of modernism: art (Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, and the Secessionists), music (Arnold Schoenberg), psychoanalysis (Freud), and architecture (Otto Wagner, Camillo Sitte, and Adolf Loss). Here as elsewhere in Europe, there were two conflicting strands of modernism, which bear a resemblance to the contrasting philosophical styles of Carnap and Heidegger. On the one hand, modern artists and especially architects appropriated modern science and technology to develop an aesthetic committed to rationality, clarity, transparency, utility, and functionalism; on the other hand, writers and artists, drawing on the work of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, and Wagner, sought to fathom the irrational depths of human subjectivity in works that are deliberately obscure, polyvalent, and functionally useless. The most influential representative of the latter tendency is Klimt, whose paintings express Freud’s eroticizing of the personality. By the time Carnap was developing his mature philosophy, this brand of expressionism was giving way to rationalism. This shift can be seen in the way Klimt’s art changes from psychologically and sexually charged canvases to his more classical, almost Byzantine, later work. The change is also evident in the transformation of the organic and fluid forms of art nouveau into the crystalline and geometric forms of art deco. A parallel change occurs between Otto Wagner’s early and late architecture. This rationalist trajectory leads to the purportedly styleless style of Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, and their colleagues at the Bauhaus. Allergic to complexity and infatuated by simplicity, minimalist philosophers echo their architectural counterparts by quietly repeating the mantra “less is more.” If logical positivism and radical empiricism share a vision of the transformative power of culture, then the difference between scientific philosophy and art might not be as great as its followers maintain. The issue is not so much art versus non-art but two different aesthetics that entail contrasting attitudes toward life.

In his provocative analysis of a seminal but long neglected book, On Growth and Form, Stephen Jay Gould writes: “As a subtle thinker, D’Arcy Thompson understood that emphases on diversity and unity do not represent two different theories of biology, but different aesthetic styles that profoundly influence the practice of science.”25 Philosophy and science are, like everything else, matters of style. In Vienna, no one was more vocal about the necessity to strip away superfluous excesses and meaningless details than the Austrian architect Adolf Loos, who was a contemporary of Carnap and the members of the Vienna Circle. In his influential book Fin-de-Siècle Vienna, Carl Schoske writes,

Loos had participated in the Secession movement in its early days, sharing its revolt against historical style. In 1898, he formulated in the Secession’s Ver Sacrum the most vigorous indictment of Ringstrasse Vienna for screening its modern commercial truth behind historical facades. The Secession artists and architects sought a redemption from historical styles by developing a “modern” style, to sheathe modern utility and new beauty. Loos sought to remove “style”—ornamentation or dressing of any sort—from architecture and from use-objects, in order to let their function stand clear to speak its own truth in its own form.26

Philosophy and art mirror each other. While art, science, and technology become functional, philosophy’s purportedly scientific program implicitly appropriates aesthetic principles to advance its practical agenda. Just as formalist architecture serves utilitarian ends, so scientific philosophy seeks to transform personal and public life. In both cases, the dismantling of tradition—be it artistic, architectural, metaphysical, or theological—is the prerequisite for the emergence of modernity.

Insofar as analytic philosophy is devoted to simplicity, purity, clarity, and transparency, it remains distinctively modern and as such is now outdated. In his influential work, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, Robert Venturi, who is largely responsible for launching postmodern architecture, might well be commenting on philosophy when writes:

Architects can no longer afford to be intimidated by the puritanically moral language of orthodox Modern architecture. I like elements which are hybrid rather than “pure,” compromising rather than “clean,” distorted rather than “straightforward,” ambiguous rather than “articulated,” perverse as well as impersonal, boring as well as “interesting,” conventional rather than “designed,” accommodating rather than excluding, redundant rather than simple, vestigial as well as innovating, inconsistent and equivocal rather than direct and clear. I am for messy vitality over obvious unity….

But an architecture of complexity and contradiction has a special obligation toward the whole: its truth must be in its totality or its implications of totality. It must embody the difficult unity of inclusion rather than the easy unity of exclusion. More is not less.27

For Venturi, style is substance, and substance is style. Rejecting every form of minimalism designed to reduce complex wholes to ostensibly simple parts, Venturi proposes an aesthetic that cultivates the contradictions that transform the work of art into an endless process as well as a finished product.

RELIGION WITHIN THE LIMITS OF STYLE ALONE

Throughout the history of Western theology and philosophy, religion has been alternatively associated with cognition (thinking), volition (willing), and affection (feeling). During the eighteenth century, many defenders and critics interpreted religious claims as primarily cognitive, i.e., they viewed them as statements about the existence or nonexistence of God, who was understood theistically or deistically, as well as about human existence and events in the world. To defend religious beliefs during a time when the modern scientific worldview was gaining influence, theologians and philosophers appropriated empirical criteria of meaning and verification to recast the traditional cosmological and teleological arguments for the existence of God. Starting from the evidence of the existence of the world and its design, apologists argued to God as their necessary cause. By the end of the eighteenth century, however, it had become clear that this strategy was ineffective because, as Hume demonstrated, the very empiricism used to defend belief actually undercut its foundation. If faith were to be rationally justified, some argued, its defense would have to be practical rather than theoretical. One of Kant’s primary motivations in his critical philosophy was to develop a persuasive argument for religion within the limits of reason alone by recasting belief in terms of moral activity rather than scientific or quasiscientific knowledge. But his analysis of the relation between thinking and willing left unresolved problems that he eventually addressed in his third critique. Through an interpretation of aesthetic judgment, Kant extends the principle of autonomy from theoretical and practical reason to the work of art understood as both the process of production and the product produced. For many of Kant’s followers, the Critique of Judgment raised the prospect of interpreting religion through art and vice versa.

While Heidegger and Carnap agree that religion can be understood in terms of art, they understand this relationship very differently. For Carnap, art, more specifically poetry, lacks referential value, and, therefore, its statements are pseudostatements, which, in the final analysis, are meaningless; for Heidegger, philosophy that is no longer bound by the assumptions of ontotheology discloses the poetic character of all thought—even scientific thought. Far from a limited genre, poiesis is the creative activity through which thinking as well as being emerge. Heidegger articulates the crucial insight upon which his thinking turns in Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, which was published the same year he delivered his lecture “What Is Metaphysics?” To understand how he moves from Kant’s critical philosophy to an interpretation of philosophy in terms of the work of art, it is necessary to turn to the third critique.

Kant’s reformulation of the principle of autonomy through the notion of “inner teleology” leads to a new interpretation of the work of art. In contrast to all forms of utility in which means and ends are externally related, inner teleology involves what Kant describes as “purposiveness without purpose,” in which means and ends are reciprocally related in such a way that each becomes itself in and through the other and neither can be itself apart from the other. He illustrates this idea by describing the interplay of whole and part in the work of art.

The parts of the thing combine of themselves into the unity of a whole by being reciprocally cause and effect of their form. For this is the only way in which it is possible that the idea of the whole may conversely, or reciprocally, determine, in its turn the form and combination of all the parts, not as cause—for that would make it an art product—but as the epistemological basis upon which the systematic unity of the form and combination of all the manifold contained in the given matter become cognizable for the person estimating it.28

Unlike art produced for the market, which is utilitarian and as such has an extrinsic purpose, fine art is produced for no external end but is created for its own sake. Never referring to anything other than itself, so-called high art is art about art and is, therefore, both self-referential and self-reflexive.

While seeming to be completely autonomous, the structures of self-referentiality and self-reflexivity are considerably more complicated than they initially appear. All such structures seem to be closed but, on closer inspection, prove to be open because they presuppose as a condition of their possibility something, which might be nothing, that they can neither incorporate nor assimilate. The interruption of the self-referential circuit of reflexivity exposes aporiae that provoke thinking sensu strictissimo and are the condition of creativity. The pivot upon which this analysis turns is the interplay of the imagination and representation in the production of self-consciousness. In self-consciousness, the subject turns back on itself by becoming an object to itself. Self-as-subject and self-as-object are reciprocally related and thus are coemergent and codependent. As such, the structure of self-relation constitutive of self-conscious subjectivity presupposes the activity of self-representation. Self-awareness, in other words, is impossible apart from the self’s representation of itself to itself. Though not immediately obvious, precisely at the point where self-consciousness seems to be complete, it approaches its constitutive limit. Dieter Henrich identifies the crucial issue in commenting on Fichte’s reading of Kant:

We might cast this question another way: Will ontological discourse always make use of the premise that something can be said about the mind that is not of the mind, and that the mind can say something that is of the mind about what is not of the mind, so that the two discourses can never be derived from one another—or even form a third discourse, thereby precluding any fully intelligible linear formulation?29

Henrich implies that the impossibility of explaining self-consciousness through linear models does not necessarily mean that the self-reflexivity of self-consciousness is circular. When consciousness turns back on itself, it discovers a lacuna without which it is impossible but with which it is incomplete. The pressing question, then, is: Where does what the self-conscious subject represents to itself come from? If self-as-subject and self-as-object are codependent, neither can be the originary cause of the other. The activity of self-representation, therefore, requires a more primordial presentation, which must originate elsewhere. This elsewhere is the limit that is impossible to think but without which thinking is impossible. “Thinking,” as Jean-Luc Nancy explains in another context, “is always thinking on the limit. The limit of comprehending defines thinking. Thus thinking is always thinking about the incomprehensible—about this incomprehensible that ‘belongs’ to every comprehending, as its own limit.”30 This limit is the edge of chaos where order simultaneously emerges and dissolves. To understand what occurs along this border, it is necessary to consider the dynamics of representation in more detail.

The problem of representation—Vorstellung—runs through all three critiques. In the first critique, Kant argues: “A concept [Begriff] formed from notions [Notio] and transcending the possibility of experience is an idea [Idee] or concept of reason.”31 In the exercise of practical reason, ideas that lie beyond experience and hence remain regulative are actualized as they become practically effective in moral activity. But the postulates of practical reason can no more be experienced than ideas and, therefore, yield no knowledge, even though they are rational. An idea or postulate, Rodolphe Gasché explains, “is a representation by a concept of the concepts that serve to represent representation with consciousness.”

Representation here translates the German Vorstellung, a term Kant uses to designate the operation by which the different faculties that constitute the mind bring their respective objects before themselves. Yet when Kant claims that in spite of the impossibility of intuitively representing (and thus knowing) the ideas, they nonetheless play a decisive role for in the realm of cognition, or that in the moral realm they acquire an at least partial concretization, he broaches the question of the becoming present of the highest, but intuitively unpresentable representation that is the idea. This is the problem of the presentation, or Darstellung of the idea, and it is rigorously distinct from that of representation. The issue is no longer how to depict, articulate, or illustrate something already present yet resisting adequate discursive or figural expression but of how something acquires presence—reality, actuality, effectiveness—in the first place. The question of Darstellung centers on the coming into presence, or occurring, of the ideas.32

Coming into presence (Darstellung) is the condition of the possibility of representation (Vorstellung). But how does such presencing or presentation occur?

In his analysis of Hegel’s concept of experience, Heidegger suggests a possible answer to this question when commenting on the claim that “science, in making its appearance, is an appearance itself”:

The appearance is the authentic presence itself: the parousia of the Absolute. In keeping with its absoluteness, the Absolute is with us of its own accord. In its will to be with us, the Absolute is being present. In itself, thus bringing itself forward, the Absolute is for itself. For the sake of the will of the parousia alone, the presentation of knowledge as phenomenon is necessary. The presentation is bound to remain turned toward the will of the Absolute. The presentation is itself a willing [emphasis added], that is, not just a wishing and striving but the action itself, if it pulls itself together within its nature.33

This telling comment makes it clear that in developing his analysis, Heidegger takes Hegel’s Wissenschaft rather than Carnap’s positivism as the model of science. His remarkable insight complicates Hegelianism in a way that opens it up as if from within. Far from a closed system, which, as a stable structure, would be the embodiment of reason or even the Logos, the Hegelian Absolute here appears to be an infinitely restless will that wills itself in willing everything that emerges in nature and history. Heidegger explains the implications of this reading of systematic thinking when he interprets the inconceivability of freedom in Kant’s philosophy in a way that points toward his own account of the groundless ground of Being: “The only thing that we comprehend is its incomprehensibility.”34 All comprehension, it seems, emerges from and, therefore, returns to what remains incomprehensible. As if rewriting Freud’s analysis of the unconscious, Heidegger insists that there is at least one spot in consciousness at which “it is unplumbable—a navel, as it were, that is its point of contact with the unknown.”35

While Kant clearly and consistently distinguishes the theoretical and practical uses of reason, he always insists on the “primacy of practical reason.” Cognition presupposes volition, but willing does not necessarily presuppose thinking. The imbrication of thinking and willing lies at the heart of the imagination. In his analysis of aesthetic judgment in the third critique, Kant offers a definition of the imagination that proved decisive for many later writers, artists, philosophers, and theologians: “If, now, imagination must in the judgment of taste be regarded in its freedom, then, to begin with, it is not taken as reproductive as in subjection to the laws of association, but as productive in exerting an activity of its own (as originator of arbitrary forms of possible intuitions).”36 The imagination involves two interrelated activities, which Kant describes as productive and reproductive. In its productive modality, the imagination figures forms that the reproductive imagination combines and recombines to create the schemata that organize the data of experience into comprehensible patterns. The argument hinges on the relation between Darstellung and Vorstellung. Theoretical and practical reason are impossible apart from representations; the activity of representation, in turn, presupposes antecedently given data that can be re-presented. The question then becomes: how does Darstellung happen, or how do representations emerge? According to Fichte, presentation is an act that “occurs with absolute spontaneity,” and, therefore, Darstellung is “grounded” in freedom. Such freedom is anarchic—it is not the freedom of subjectivity but the freedom from subjectivity through which both subjectivity and objectivity are given. From this point of view, being is donation.

While autonomy is self-grounded, an-archy is groundless. It “is not the diffraction of a principle, nor the multiple effect of a cause, but is the an-archy—the origin removed from every logic of origin, from every archaeology.”37 Heidegger describes the an-archy of freedom glimpsed in the presentational activity of the imagination as an abyss. In Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics, he explains: “In the radicalism of his questions, Kant brought the ‘possibility’ of metaphysics to the abyss. He saw the unknown. He had to shrink back. It was not just that the transcendental power of the imagination frightened him, but rather that in between [the two editions of the first critique] pure reason as reason drew him increasingly under its spell.”38 This abyss or Abgrund from which all determination emerges is the groundless ground that is indistinguishable from nothing. Such an unfathomable ground is the no-thing on which everything depends and every foundation founders. Contrary to expectation, it is Hegel who explains the relationship between nothingness and freedom: “In its highest form of explication nothingness would be freedom. But this highest form is negativity insofar as it inwardly deepens itself to its highest intensity; and in this way it is itself affirmation—indeed absolute affirmation.”39 Negativity is affirmative insofar as it is the condition of the creative emergence of everything that exists. Just as God creates freely ex nihilo, so the productive imagination creates freely out of nothing. This “is” the nothing that nothings or nihilates by giving the gift of being itself. Nothing, which is the condition of the possibility of whatever exists, is never present and, therefore, cannot be represented; nor, of course, is it absent. Far from subverting thought, this nothing keeps thinking in play.

At this point, the differences between Carnap’s argument, which takes a dated understanding of the natural sciences as a model for philosophy, and Heidegger’s use of art to reinterpret philosophy and technology become evident. In contrast to so-called scientific philosophy, which presupposes that meaningful statements are referential and, thus, representational, Heidegger argues that the task of philosophy is to think that which eludes reference and resists representation. So understood, philosophy does not abandon critical thinking; to the contrary, when philosophical analysis is pushed to its limit, one encounters contradictions that are the conditions of the possibility of thinking itself. As Gasché points out,

Aporia is thus not something negative. It is what allows the limits constitutive of philosophical thinking to be drawn, but, as limits that are neither pure nor undivided, they are crossable and consequently impossible limits. Far from being a flaw, the fundamental aporia of death in Being and Time represents the condition from which philosophical thought draws its very possibility; at the same time, however, this enabling condition undermines the claims that philosophical discourse makes for itself.40

What Carnap’s scientific philosophy regards as the source of error is, for Heidegger, the origin of truth. While setting itself over against theology and art, “scientific” philosophy, Heidegger argues, actually extends the will to power characteristic of Western metaphysics. To subvert the will that would construct the world in its own image, he argues, it is necessary to return to the origin of the work of art by asking: what is the work of art?

Art, understood as poiesis, is the activity of figuring form in and through which determinate objects as well as the words and concepts with which they are apprehended are articulated. The correspondence between word and thing, which traditionally has been identified with truth, requires differentiation, which, in effect, presents whatever is present. Heidegger labels such presencing “unconcealment”—Aletheia, which, he argues, is truth.

Aletheia, as opening of presence and presencing in thinking and saying, originally comes under the perspective of homoiosis and adaequatio, that is, the perspective of sense and correspondence of representing with what is present. But this process inevitably provokes another question: How is it that aletheia, unconcealment, appears to man’s natural experience and speaking only as correctness and dependability? Is it because man’s ecstatic sojourn in the openness of presencing is turned only toward what is present and the existent presenting of what is present? But what else does this mean than that presence as such, and together with it the opening granting it, remain unheeded? Only what aletheia as opening grants is experienced and thought, not what it is as such.41

So interpreted, truth is an event that can be neither experienced nor thought properly. Instead of the accurate representation of an object to a subject, truth is the opening between subject and object that makes both representation and correspondence possible. This interpretation of truth involves an understanding of language that is completely different from that of logical positivists and linguistic analysts. For Heidegger, language does not represent antecedent entities but forms entities that can, in turn, be represented. This formative activity is the poiesis that defines the work of art. Language, therefore, is essentially poetic, and poiesis is the unconcealment that is the event of truth.42 As our consideration of the interplay between Vorstellung and Darstellung suggests, such unconcealment is inseparable from concealment; there is no showing that is not at the same time hiding. The work of art performs the impossibility of representation, which is the origin of being and thinking.

There is much in being that man cannot master. There is but little that comes to be known. What is known remains inexact, what is mastered insecure. What is, is never of our making or even merely the product of our minds, as it might all to easily seem. When we contemplate this whole as one, then we apprehend, so it appears, all that is—though we grasp it crudely enough.

And yet—beyond what is, not away from it but before it, there is still something other that happens. In the midst of beings as a whole an open place occurs. There is a clearing, a lighting. Thought of in reference to what is, to beings, this clearing is in a greater degree than are beings. This open center is therefore not surrounded by what is; rather, the lighting center itself encircles all that is, like the Nothing we scarcely know.43

“The Nothing we scarcely know” is the nothing that nothings, the nothing that nihilates. Never reducible to syntax or semantics, the work of art presents what can never be represented. Another name or, more “properly,” pseudonym for this Nothing is God.

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.44

If there is nothing outside or beyond style, we might say of modern philosophy what Venturi said of modern architecture: non-style has become modernism’s preferred style. This insight points to a suggestive analogy—analytic philosophy : modern architecture :: continental philosophy : postmodern architecture. While modern analytic philosophy seeks secure foundations in clear concepts and verifiable facts, postmodern continental philosophy reveals the absence of ground in artful works that turn us toward what is always turning away. The most interesting philosophers realize what the best scientists also know: there is an undeniable poetic aspect to their work. And the best artists and writers know that there is an undeniable philosophical—even theological or a/theological—dimension to their work.

The difference between the two approaches I have been considering does not, then, involve the opposition of two types of philosophy of religion but the contrast of two ways of thinking, writing, and even living—one acknowledges and cultivates the poetic, artistic, and literary characteristics of creative work, and the other denies and represses them. As Freud has taught us, however, the repressed never disappears but remains to haunt those who try to deny it. When analysis becomes critical, it bends back on itself and solicits the return of the repressed. This revenant inevitably disrupts the structures and systems—psychological, religious, social, political, and economic—designed to contain it. What is repressed always remains irreducibly ambiguous because it not only repels but also attracts. Order, after all, becomes repressive, and disruption can be both liberating and transforming.

Heidegger underscores this insight in an important essay entitled “The Question Concerning Technology,” where he quotes Hölderlin, one of his two favorite poets:

But where there is danger, there grows

Also what saves.45

Having argued that the will to mastery embodied in modern science and technology has turned destructive and threatens the entire planet, Heidegger now unexpectedly suggests that this mortal danger harbors hope. This twist in his thinking results from his realization that technology has not always been what it has become during the modern era. “There was a time,” he writes,

when it was not technology alone that bore the name techne. Once that revealing that brings forth the truth into the splendor of radiant appearance was also called techne.

Once there was a time when the bringing-forth of the true into the beautiful was called techne. The poiesis of the fine arts was also techne…

The arts were not derived from the artistic. Art works were not enjoyed aesthetically. Art was not a sector of cultural activity.

What was art—perhaps only for that brief but magnificent age? Why did art bear the modest name techne? Because it was a revealing that brought forth and made present, and therefore belonged within poiesis. It was finally that revealing that holds complete sway in all the fine arts, in poetry, and in everything poetical that obtained poiesis as its proper name.

Far from being opposed, art and technology were once complementary expressions of human poiesis—art as techne, technology as art. Rethinking “the essence of technology” in terms of poiesis displaces the will to mastery with a style of thinking that creates the possibility of transforming both self and world. Heidegger continues,

The same from whom we heard the words

But where danger is, grows

The saving power also…

says to us:

… poetically dwells man upon this earth.46

To dwell poetically would be to transform art into life and life into art.

As I have noted, elsewhere I have argued in words that are far from artful, “religion is an emergent, complex adaptive network of symbols, myths and rituals that, on the one hand, figure schemata of feeling, thinking and acting in ways that lend life meaning and purpose and, on the other, disrupt, dislocate and disfigure every stabilizing structure.”47 From this point of view, there are two interrelated moments in religion—one structures and stabilizes, and the other destructures and destabilizes. These two moments, which correspond to the two styles of philosophy we have been considering, are inseparable and alternate in a quasi-dialectical rhythm. One style seeks the clarity, precision, and verification that can provide certainty and security by repressing disruptive emergence; the other style deliberately traces the elusive excess, remainder, and supplement that both harbors disruption and promises transformation.

These alternative styles of philosophy, in turn, reflect different deployments of the imagination. Heidegger’s account of the interplay between Darstellung (presentation) and Vorstellung (representation) points to two sides of the imagination, which the poet Coleridge, commenting on the philosopher Fichte, labels “primary” and “secondary.”

The imagination, then, I consider either as primary, or secondary. The primary imagination I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception, and as repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM. The secondary Imagination I consider as an echo of the former, coexisting with the conscious will, yet still as identical with the primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in the degree and the mode of its operation.48

In these seminal lines, art, philosophy, and religion intersect in a way that makes it impossible to be sure where one ends and another begins. The implications of Coleridge’s provocative claim become clear over a century later in the work of the person who is, in my judgment, the most important modern poet, Wallace Stevens. The bridge between these two poets is the philosopher who most deeply influenced Stevens: Nietzsche.

In his philosophical fragments and unscientific postscripts to postscripts, Nietzsche develops an aesthetic a/theology that, like Kierkegaard’s philosophical vision, can be communicated only through aesthetic indirection. Both his supporters and critics repeatedly misunderstand and misrepresent Nietzsche’s notorious declaration of the death of God because they overlook an important qualification. The god who dies, Nietzsche argues, is the transcendent moral God: “At bottom, it is only the moral god that has been overcome. Does it make sense to conceive a god ‘beyond good and evil’? Would a pantheism in this sense be possible? Can we remove the idea of a goal from the process and affirm the process in spite of this?”49 Though Nietzsche never mentions Kant, he appropriates his interpretation of the beautiful work of art in terms of “inner teleology” or purposeless process to argue that the world itself is, in effect, a work of art whose purpose is nothing other than itself. The death of the moral God creates the possibility of the birth of the divine artist whose creative activity is no longer transcendent but has become immanent in the activity of the imagination.

In his early work, Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche writes,

throughout the book I attributed a purely aesthetic meaning—whether implied or overt—to all process: a kind of divinity, if you like, God as the supreme artist, amoral, recklessly creating and destroying, realizing himself indifferently in whatever he does or undoes, ridding himself by his acts of embarrassment of his riches and the strain of his internal contradictions.

This process has two sides—Apollonian and Dionysian—that correspond to the two rhythms of religion and express the correlative operations of the imagination. While the Apollonian is “the principium individuationis” that establishes “just boundaries,” the Dionysian transgresses fixed limits and tends “toward the shattering of the individual.” These two tendencies are neither separate nor opposed; to the contrary, Dionysus needs Apollo as much as Apollo needs Dionysus. Dionysus upsets and dislocates the stabilizing structures that Apollo fashions, and Apollo creates the order Dionysus disrupts. In this way, if Dionysus puts into play the productive imagination that operates in Darstellung, and Apollo taps the reproductive imagination as well as the two guises of the “supreme artist” that Nietzsche names God, then God and the imagination are one.50

It was left for Stevens to expand Nietzsche’s notion of art and the artist to include creative activity as such. Heaven and earth meet in “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven.”

The endlessly elaborating poem

Displays the theory of poetry

As the life of poetry. A more severe,

More harassing master would extemporize

Subtler, more urgent proof that the theory

Of poetry is the theory of life…51

The creativity that transforms life into art and art into life is not merely human, and the poetry that is the theory of life is not merely a literary genre but is the “substance” of all things visible and invisible. If, as Heidegger, quoting his other favorite poet, Rilke, insists, “Only a god can save us now,” my wager is that the God that saves at this late moment is the imagination.52 The artful logic of the poet remains the last word.

Proposita: 1. God and the imagination are one. 2. The thing imagined is the imaginer.

The second equals the thing imagined and the imaginer are one. Hence, I suppose, the imaginer is God.53

0

0

0

Religion, Philosophy, Art, Literature, Technology

a neχus

almost infinite

perhaps divine