There is a lot to be learned from climbing mountains, more than you might think about life, about saving the Earth, and of a little about how to go about both. Tough mountains build bold leaders, many of whom, in the early days, came down from the mountains to save them.

DAVID BROWER, LET THE MOUNTAINS TALK, LET THE RIVERS RUN

In the summer of 1918, when David Brower was six years old, he took a trip with his family to the Sierra Nevada and Yosemite that was so memorable that he could recall it in great detail for the rest of his life. The journey with his parents and two siblings took days as their two-year-old Maxwell traversed packed-dirt, one-lane mountain roads. In Yosemite, he rebelled on the trail to Vernal and Nevada Falls, refusing to cross the surging Merced River on a fat log that protected crossers with only a rail on one side. He was equally stubborn the next day on the hike to Sentinel Dome, retreating to the Maxwell for a nap. Each night the family slept under the stars, and young Brower would fall to sleep to the wails of train whistles. It was only years later that he realized that one of those engines that he heard on those star-speckled mountain nights was laboring to destroy a paradise. It was toiling to build the O’Shaughnessy Dam, which would flood the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Construction had been authorized in 1913, and laborers then spent nearly a decade devastating a valley that John Muir had failed to save.

1 At the end of the journey, the family returned to the then-modest college town of Berkeley, California, where Brower had been born on July 1, 1912, and where he would make his home for the rest of his life.

His parents had taken different paths before settling in this community on San Francisco Bay, where there were no bridges and the surrounding hills were still wild. His father, Ross, came originally from Bath, Michigan, and had traveled west with his father, Gideon Samuel Brower. The Brower family name in America could be traced back to the seventeenth century with the arrival of the Dutch immigrant Jacob Brower. Gideon was a talented carpenter who built a railroad station in El Paso, Texas, before moving on to Fresno and California’s Central Valley. According to his grandson, Gideon was a friend of labor leader Samuel Gompers and ran for governor of California on the Socialist ticket. This, David Brower pointed out, “was not a route to success.” He also remembered that his grandfather usually had presents in his pockets for the children when he came to visit.

2 Gideon was married twice, and one of the wives, the formidable Susan Carolyn McKay Brower, would make an indelible mark on the family.

David’s mother, Mary Grace Barlow, was born on a farm in Two Rock Valley, just west of Petaluma, California. David never knew his grandfather Barlow, who died seventeen years before David was born. His memory of his grandmother Barlow was also dim; he recalled that she died of a stroke when he was only five years old.

3 The family farm passed to Mary’s half-sister Francis, whom the children called Fanny, and David and his siblings were often there. It was primarily a chicken ranch, although it also had some sheep, pigs, and cows as well as an orchard. On the farm over the years, Brower learned most aspects of farming, from pruning and plowing to milking cows and castrating pigs.

4According to Joseph, their youngest son, Ross Brower and Mary Grace Barlow met at the First Presbyterian Church in Berkeley and married in August 1906. Ross had enrolled at the University of California in Berkeley and earned his engineering degree in 1900. Since then he had been working as a draftsman and an electrician. Like his father, he was good at fixing things, friendly and attentive. He also had a love for the outdoors, as did Mary. Her degree was in English in 1905, also from the University of California. She got her master’s a year later from Stanford University, shortly before the wedding.

5After their marriage, the young couple moved to Michigan, where Ross Brower earned a master’s degree in engineering. Edith was born in Ann Arbor in 1907. The family returned to Berkeley, where Ross found better employment, first an engineering post at the Union Iron Works and then posts teaching in the Oakland school system and the University of California. A son, Ralph, was born in 1909, followed by David in 1912. For a while, the family rented an apartment in a twelve-unit apartment complex owned by Susan Carolyn McKay Brower, whom young David would call “Grandmother Brower,” on Haste Street, four blocks from the Cal campus. Ross, Mary, and their children would rent one of the units off and on over the next few years before acquiring a half-interest in the complex and then becoming its legal owners by 1918.

6Susan Brower may have sold the apartment house and moved to Los Angeles, but when she returned for visits, her personality overwhelmed all of the Browers. She was a dowager. She brooked no nonsense, and she never hesitated in expressing her opinion. She also maintained a fierce work ethic. She would arise at 5:00

A.M. and work tirelessly, although never on Sunday. Her religious fervor was fundamentalist Baptist, in contrast to her daughter-in-law Mary’s Presbyterianism. David Brower discovered the sheer force of his grandmother’s will when she prevailed in having him “dunked in the Baptist style.” His mother was “disturbed” by the act. But that was nothing compared to what happened when eight-year-old David went into the hospital to have his tonsils removed: Susan Brower convinced the doctors to wield their scalpels elsewhere, and David awoke from anesthesia to discover he had been circumcised.

7 She was a great apostle against sin and ensured that her son Ross was a disciple. Gayle Brower liked to tell a story about the reception held after she married Joseph, David’s younger brother. It was at their new home, and all they could afford to serve was spaghetti, bread, and red wine. When Gayle walked into the kitchen before most of the guests had arrived, she discovered her new father-in-law, Ross Brower, pouring the wine down the sink. Susan Brower had preached against consuming alcohol, and Ross abided by that dictum. The woman, said Gayle, had declared “that there would be no dancing, no whiskey, no drinking, no women, and nothing that was considered fun.”

8David Brower also reported that neither his grandmother nor his father “had anything to do with alcohol, tobacco, coffee, cards or dancing.”

9 But their sermons did not stick. David smoked, giving it up finally in 1959, one year before his father died. He never quit alcohol. His introduction to it came shortly after he was twenty-three years old and still living part of the time at home. Ross, in a letter to his son, said that he had found a jug in a recess of the phonograph cabinet that smelled like wood alcohol. David replied in a long rambling letter, confirming that it was wine. He attempted to justify his decision to drink in moderation. He had never actually gotten drunk from drinking, he said, although he might try it some day. Ross seemed slightly nonplussed by the confession but admitted he could not dictate whether his son drank.

10 During his life, David sometimes did drink heavily, from the notorious two-martini lunches to the 4:00

P.M. cocktail hour at home and the late-night forays until the bars shut down. Some of his associates worried that alcohol too often affected his performance.

11 But as with many aspects of Brower’s life, views were mixed on how much his drinking affected him.

Until 1920, the Browers lived a prosperous, comfortable, middle-class life with every expectation that this life would continue. Then it all changed. After the birth of Joe, Mary Brower had trouble recovering. In the hospital, her condition deteriorated. She lost some of her hearing and then her sight. The doctors were helpless. It took a very long time before they finally diagnosed that she had an inoperable brain tumor. It also took a long time before she was able to go home. When she did, she was an invalid.

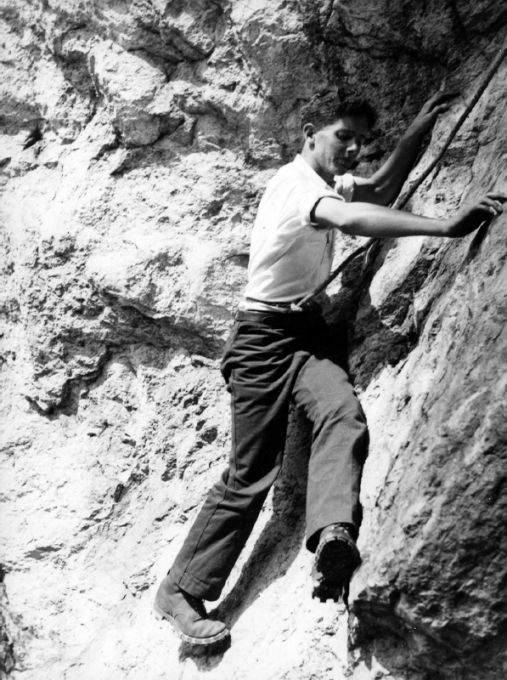

David Brower’s

writings and his statements in interviews sought to cast his mother in those subsequent years as “valiant.” He poetically described hikes with her in the Berkeley hills. She had been a good walker before she became ill, and she could still get around fine as long as someone led her. David became her eyes on these hikes. He described not only potential hazards on the trail but also the beauty of the natural surroundings. He said he gained his power of description from many of those walks. He remembered other such scenes, too, such as when she sat in the front parlor playing Rachmaninoff and Liszt on the family’s Ludwig piano or when she stopped “whatever she was doing, listening attentively, with a pleased smile” while he played (

figure 1).

12

Brower’s mother would often stop whatever she was doing so that she could listen to her son play the piano. He continued to play throughout his life, sometimes sharing the keyboard with Ansel Adams, who had once studied to be a concert pianist. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Those days were rare. Her incapacities meant that she could no longer reliably take care of the children, including a new infant, nor could she care for the house or the tenants. Sometimes she would be stricken with spells, terrible seizures, which confined her to her bed. She turned to God and became devoutly religious. She would crank up the family radio so loud that the entire neighborhood could hear “The Country Church” or “The Hour of Prayer.”

13By then, Ross Brower had lost his teaching position at the University of California. No longer able to leave his wife or small children alone, he became a full-time landlord of the twelve units on Haste Street. He expanded the two-story Queen Anne Victorian on the front of the lot by building dormers in the attic where the children could sleep. Tenants were students, working people, and seniors. Rents were low, but filling the house was always a challenge, even more so once the Depression struck. Ross also got part-time employment at the University of California Extension Division, hawked fire extinguishers for a time, and lost what little inheritance they had on bad real estate investments. He was not a good businessman.

14 A young woman who was a tenant in the house described how Ross once agreed to rent her a room for the ridiculously low price of $10 a month because it was all she could afford. What impressed her the most, though, was not his generosity but his devotion to his wife.

15Mary Brower’s spells

would be hard on the family. When their mother was ill, one of the children often stayed home from school as an extra caretaker. When she was feeling better, she could sometimes do light housework, especially sweeping the stairs. At one point when David was away from home, Edith told him in a letter that their mother had not been well for two weeks and that she had taken a fall that knocked her unconscious. Mary died suddenly in December 1939 at the age of fifty-seven. Joe Brower remembered that his mother was stricken with a seizure in the bathtub and drowned.

16 By the beginning of America’s entry into World War II, Ross Brower had married Mae Gabrielson, who had children of her own, and David Brower no longer felt comfortable in the house of his youth with a new stepmother, stepbrothers, and stepsisters. Ross Brower would also die suddenly, but not until 1960, when he was eighty-one. The Haste Street apartments passed out of the Brower family, although locally the buildings are still called the “Brower house.”

17As for the Brower children, Edith grew into a tall, statuesque beauty who sang, played the piano, and won the California state typing championship. She enrolled at the University of California but did not graduate, and when she was twenty-one, she defied her father’s wishes and married her childhood sweetheart. Her oldest brother, Ralph, excelled academically and graduated from Cal with an engineering degree. He was a stickler for details, and in later years the engineer whose task was to build did not always agree with the brother who espoused nature over development. While the four siblings were growing up, the responsibility for watching Joe, who would later become a commercial airline pilot, fell primarily on David, who was eight years older. Joe said David never complained when he tagged along with his big brother on hikes or for neighborhood football games. David was always fair, insisting that everyone be picked for a team, no matter how scrawny or young. “Oh, he was a very good big brother, as good as one could have,” recalled Joe. Yet as hard as Ross Brower and his children tried to make Haste Street a normal household after Mary became ill, it still lacked a maternal, feminine touch, according to Gayle Brower, Joe’s wife. The Brower children did not learn how to dance; they did not learn the proper etiquette of writing thank you letters; and if they had friends over, those children were rarely invited inside. “Social graces,” she said, “were often lacking in the Brower children.”

18David also excelled academically, eventually skipping three grades in grammar school, though that likely exacerbated his social standing with his decidedly younger classmates. By junior high school, he experienced a series of illnesses that often kept him out of the classroom. He missed nearly a term when he had the mumps, then impetigo, and then burns when gas from the hot-water heater at home blew up when he was attempting to relight the pilot.

19In

1925, at the age of thirteen, David discovered butterflies. Two young tenants, Al and Fred Furer, living in the Haste Street apartments with their parents, introduced him to this past-time. Brower began collecting, keeping a journal, where he laborious typed each entry into a small notebook. By the end of the summer, he had captured and mounted thirty species and became enthralled by the science of entomology. The next year he roamed the Berkeley hills and even took a trip to Yosemite to add to his collection. His greatest success came April 17, 1928, marked precisely in his journal, when he found a butterfly so unusual that he could not locate mention of it in any of his guidebooks. Its key distinction was that it had an orange tip. By now, Brower was communicating with other butterfly collectors, and one of them, Jean Gunder of Pasadena, California, paid Brower $10 for the specimen and then had it officially named “Broweri.” It was only later that Brower realized that the butterfly probably had been a transition form, a mutation, just an oddball. “It might just be one,” he said. “So that was really an endangered species, and I killed it. I wiped it out.”

20Roaming the hills with a butterfly net could be perceived as effeminate and markedly different from the behavior of his peers. In the hills, when he spotted someone approaching, Brower would combat this self-conscious “oddball” image he had of himself by breaking into song or whistling, preferably a popular show tune of the day. Collecting, said Brower, was lonely, ostracizing, and even embarrassing.

21A new neighbor, Donald Rubel, arrived to help end the loneliness. Rubel was everything Brower wanted to be. He was sturdy, good-humored, and even witty at times, and most of all he was a good athlete. Where the Brower family was scrapping for cash, the Rubel family was comfortable. Don’s father was employed at the university’s Agricultural Exchange; they had a new home, a Steinway piano, and two Dodges. More importantly, though, Rubel introduced Brower to football, installing him as a guard on the Regent Street Varsity, a motley football sandlot squad whose home field varied around the neighborhood. Brower knew so little about football that at first he tried to block and tackle on both offense and defense. But by the time he was in high school, he could toss a football 60 yards down the field and recite the score of seemingly every gridiron encounter between Cal and its archrival Stanford. He would eventually grow to be six feet, two inches tall, but when he entered Berkeley High School, he was two to three years younger than his peers. It was obvious that Brower did not have the physique—in his words he was “too skinny”—to make the famed Berkeley Bees.

22What he made up for in improved social standing, however, he lost in the classroom. He had to repeat both Algebra 3 and 4, and he admitted that he did his share of procrastinating on academics in high school. But because of his grade-school advancements, he graduated midyear when he was sixteen. He enrolled immediately at Cal. His academics did not improve. Plus, he continued to struggle socially. He pledged to a fraternity and remembered the day several of the brothers made a quick inspection of his living quarters on Haste Street. They rejected his application. He was younger, poorer, and probably less prepared for college than others, and by his third semester he dropped out. By then, he was working most of the year for a candy manufacturer in San Francisco and at a camp during the summer. An entry in his diary at the time said that it was painful to leave college, but at least he was earning enough money to help the household.

23Brower blamed his father for pushing him to start immediately at Cal after high school graduation. Don Rubel graduated from high school at the same time, but Brower believed that Rubel fared better in college because his parents withheld any pressure, and Don entered in August instead of January. The lack of a degree foreclosed some opportunities for Brower but may have opened others. Following World War II, when Brower was approached about taking a position in the history division of the War Department in Washington, D.C., in the letter accompanying his application he wrote that he wished he could have gone farther in college, but only because the degree looked better on job applications. The reply kindly but bluntly told Brower that without a degree he could not be hired. In the 1960s, when he was campaigning to save the Grand Canyon, he would joke that he had graduated from the University of the Colorado River. Brower’s future wife, Anne, believed Brower was lucky not to have finished at Berkeley because it might have pigeon-holed him in a lesser career. “David dropped out of school,” she would say, “before they could teach him what he couldn’t do.”

24Stymied, Brower discovered mountain climbing. In the summer of 1933, when he was twenty-one, he spent several weeks with his friend George Rockwood hiking in the Sierra Nevada. One night Brower arrived in the small dining room at Glacier Lodge to discover a mountain-climbing legend, Norman Clyde. Since Clyde was having dinner by himself, Brower and Rockwood joined him, and soon they were swapping tales of hiking and climbing. Clyde would eventually summit a thousand peaks in his lifetime and make 130 first ascents in the Sierra Nevada, but by 1931 he had already opened up a new era of alpine climbing as a member of the first party to scale the steep east slope of Mount Whitney. He often climbed solo, and he carried an enormous pack. He had a long waist and short legs, and he dressed in a way that exaggerated that look. He did not present as a world-class climber. Clyde was also quick-tempered and irascible. He had lost his job as a high school principal five years earlier by firing shots over the heads of Halloween vandals. He was on his way to becoming a recluse, often living out of his car or in deserted cabins.

25On this night at the Glacier Lodge, a mountain resort at 8,000 feet in the eastern Sierra Nevada, Brower had his own climbing story to tell. He had been climbing nearby in the Palisades, which at 14,000 feet have one of the grandest views in the Sierra Nevada. Brower had left Rockwood behind and was scrambling up a vertical rock column called the Thumb. He saw some holds and grabbed one, but the rock was rotten, and it broke, careening down 75 feet. Desperate and about to fall, Brower reached out with his left hand and with three fingers caught another hold before he could slip. Shaken, he cautiously moved to where he could rest and be more secure. Clyde told Brower he needed to learn more about climbing and especially about the three-point suspension. In difficult situations, Clyde said, Brower should make sure that three limbs were in safe, secure holds before using the fourth to reach for the next hold. It was good advice; Brower used it a few days later in climbing the North Palisades and would use it the rest of his climbing career.

26That seven-week trip in 1933 with Rockwood was noteworthy for two other chance encounters. One was with a college student, Hervey Voge, who was hiking the opposite way on the John Muir trail. Voge was to become a good friend and climbing companion, but his advice at this first meeting was especially helpful. He told Brower that if he was that interested in climbing, some of the best mountaineers were in the Sierra Club. Voge was a climber and a member. Brower should join. The second encounter was in Hutchison Meadow, high in the Sierra. Brower in the distance saw a bearded man carrying a tripod and camera. When the man got closer, Brower correctly guessed his identity and addressed him: “You must be Ansel Adams.” Brower had already been reading the

Sierra Club Bulletin, which often featured Adams photos. Adams, Brower, and Rockwood lingered in the meadow for a moment as Adams complained about the cumulus clouds that were too fuzzy to photograph, and then they parted.

27Brower’s interest in mountain climbing could not have come at a better time or place. The dawn of modern mountain climbing in the American West had begun, and the leading players would include this San Francisco–based hiking club and the glacial granite cliffs of Yosemite. A famous British climber, Robert Underhill, had started working with a cluster of Sierra Club climbers, including Clyde. Over the next decade, this group of climbers, along with late converts such as Brower, would make a name for themselves. Brower would be credited with thirty-three first ascents of peaks in the Sierra Nevada, and he eventually reached every 14,000-foot or higher summit within that range. He and his comrades arrived on the mountain-climbing scene at a time when the technology of mountaineering was undergoing a transformation. Tools such as pitons and carabiners, which were pounded into the rock to anchor ropes and mountaineers, were allowing climbers to reach what in the past had been insurmountable summits.

28The Sierra Club climbers, both men and women, trained every Sunday at Cragmont Rock in the San Francisco Bay area. The climbers gave code names to the various cliffs and rock outcrops; the training was rigorous; and it was led by Richard “Dick” Leonard.

29 Leonard was methodical in jotting down notes on attendance, training, and climbs, and he worked out a detailed system to rate various climbers. In one of the scorecards Leonard recorded in 1933, Brower was ranked tenth best out of the seventeen. He had one of the lowest scores for experience, which was understandable considering how fresh he was to the sport. He scored one of the highest rankings for climbing technique and in the midrange for judgment. Brower learned quickly, and soon he asked Leonard and Voge to sponsor his membership into the club. They did.

30The next summer, in June 1934, Brower and Voge headed to the mountains to test their climbing expertise. They wanted to “peak bag”—to climb to summits, no matter how low or easy, where there were no records of anyone venturing there in the past. Some of these climbs did require ropes or even a piton or two. At one point, Norman Clyde, who agreed with their goals, joined them. Clyde, said Brower, was a fellow peak bagger.

31 In an account of the trip, Voge described one day when at 5:00

P.M., after a full day of climbing, he elected to return to camp and make dinner, but Brower and Clyde decided to investigate one more peak. They did not return until midnight, having made first ascents on three other peaks. That, wrote Voge, indicated how strong the lure of climbing could become.

32Over the next few years, Brower would make Yosemite and its many cliffs his climbing goal. More important than the conquests was the realization that he enjoyed the challenge, the adrenalin rush of the climb, and the gusto and recognition atop the summit. He sought first ascents; he tallied his records and hustled to get them recognized and publicized. He would lie on the bed in his third-floor room on Haste Street gazing up at topographical maps secured to the ceiling, reviewing triumphs and planning future ventures. He would write long letters to friends and relatives detailing his accomplishments. He would sell complete climbing tales to local newspapers and then eventually to major publications such as the Saturday Evening Post and National Geographic.

His first significant public exposure came in the summer of 1935 as part of a team that challenged Mount Waddington in British Columbia. The 13,260-foot peak was 200 miles north of Vancouver. Brower called Waddington a “killer mountain” that was “impregnable,” especially the last 60 feet to its rock-ribbed true summit. It was pounded by 200 inches of rain a year, and in the summer blizzards would be followed by sun, increasing the avalanche danger. Twelve previous attempts to climb it had failed, and one climber had died. The climbing crew was organized by Leonard and headed by another Sierra Club veteran, Bestor Robinson. They spent months preparing. Brower financed his trip by negotiating a $300 contract to write dispatches for the North American Newspaper Alliance.

33Seaplanes in late June 1935 dropped the team off at sea level, more than 13,000 feet below Waddington. They spent two weeks on reconnaissance missions, carrying their gear up through dripping emerald forest to icy-white glaciers. Finally, with only a few days left, they camped on Angel Glacier at 12,550 feet. Brower and four other climbers began a final reconnaissance trip to the snow summit, which they knew would be short of the true summit. Two hours later, the first climber, Jules Eichorn, reached the snow summit and exclaimed, “My God, look at that!” The others scrambled up and stood for a moment transfixed. None of the photos they had studied, none of their telescopic reconnaissance from lower base camps, had prepared them for what was ahead. The true summit was a rocky pinnacle, with knife edges steep and polished. Those rocky faces fell on most sides for thousands of feet to icy glaciers below. The climbers debated routes and finally agreed to retreat and try again the next morning. But that night a violent blizzard arose. They had camped in the lee of the lip of a large crevasse, but “the wind shook the tents with a dreadful fury,” Leonard wrote. “The fabric snapped like pistol shots.” It was still snowing the next morning, and the team knew that they had run out of time; it would take too long for this latest storm to clear for them to reach the summit. They retreated. The next year Leonard, Robinson, and a new team that included Voge mounted a second failed attempt of Waddington. Brower could not make that trip. A rival climbing club finally succeeded later in the summer of 1936.

34The Sierra Club climbers were at the forefront in the climbing community because of their embrace of new equipment, a tactic led by Leonard, who did not tolerate failure. Four years older than Brower, Leonard was born into a military family that traveled often before they settled in Berkeley when Leonard was fourteen and his father had died unexpectedly. He was an excellent athlete and a disciplined student at the University of California. He studied geology, chemistry, and electronics before going to law school and starting his own very successful firm that specialized in business law. When Leonard took up climbing, he seized on the idea of using pitons, which were wrought-iron eye spikes; carabiners; large oval snap rings; and nylon rope that was more flexible than other alternatives. Leonard dramatically demonstrated why this new equipment was so important by assaulting the Cathedral Spires, two massive pillars lining one end of Yosemite Valley. Both were considered unassailable. After two unsuccessful attempts to scale them, Leonard returned for a third attempt in April 1934 and finally prevailed, stunning many in the mountaineering community but scandalizing some because the climbers used pitons unsparingly.

35When Leonard attacked the Cathedral Spires, he was also assaulting the sport of mountain climbing. Until this point, the sport was rooted in the philosophy of Victorian Britain that ranked the types of tools that Leonard, Brower, and others were employing as secondary to the climber’s wits and ardor. Leonard’s gear was not considered “sporting”; some critics even suggested it was cheating. Interestingly, the discussion had more to do with honor and far less with the environmental aspect of placing iron in rock and defacing nature. Leonard and others argued strongly that the reason they used tools such as pitons was primarily to ensure the climber’s safety. Obviously, however, it also gave them a decidedly new advantage over climbers of the past. Members of the Sierra Club often argued among themselves about these ethical concerns, and Brower was an integral part of that debate. In a letter he wrote in 1936, he conceded that there was still considerable leeway and judgment on deciding when a mountain route needed pitons and rope and when it was safe to go ropeless. In other words, the line between being safe and having an advantage could be blurry. But neither Brower nor others spent much time discussing how they might be scarring the mountains that they held so dear.

36Brower had missed the second Waddington climb because by then he was working and living in Yosemite Valley, doing publicity work for the park. Brower relished living in Yosemite. By his second winter, he had become an adept skier and a winter mountain climber. He notched a number of winter first ascents. But success could give way to overconfidence and poor judgment. One summer day Brower convinced an office worker with no climbing experience, the man’s wife, and their four-year-old son to accompany him up the side of a Yosemite cliff. What may be one of the most surprising aspects of this story is not just that Brower made a mistake, but that he did not even seem to be aware of it when he described the journey in letters to Leonard and Voge. Here was another Brower characteristic that would periodically crop up: at times he could make positively brilliant judgments, but at others he could make seriously flawed decisions. And he often could not recognize or acknowledge his error.

The four of them began their afternoon venture by climbing up the rocky Bridal Veil Creek by way of a chute at the Lower Chimney Rock, which is on the south side of Yosemite Valley directly opposite the granite cliff of El Capitan. Farther west the creek plunges and becomes, especially in the spring, the spectacular Bridal Veil waterfall. The family used ropes without a problem, Brower said, although when he got to one large rock, he literally had to push the woman and the child over. He reported that the family seemed delighted by Bridal Veil Creek, and at 4:00

P.M. they needed to head back. That’s when problems surfaced. The woman, who had been far more frightened than she had let on to Brower on the way up, announced there was no way she was going to descend by the same route. Brower knew an easier way down beyond Upper Cathedral Rock, but there were no trails, and they would have to go cross-country. He carried the young boy, Stuart, across what seemed like acres of manzanita and scrub oak, up and down ledges, even killing a rattlesnake at one point, until it became quite dark, and they still had a 2,000-foot descent ahead of them. They decided to spend the night on the mountain. Fortunately, Brower had brought some emergency provisions; there was water from the creek, but no flashlight. The next morning they made it down without incident. Brower said that the couple told him that the climb had been unique and enjoyable. He did not indicate that they had any complaints, although he did mention that he had dispensed aspirins to them the night they spent on the mountain.

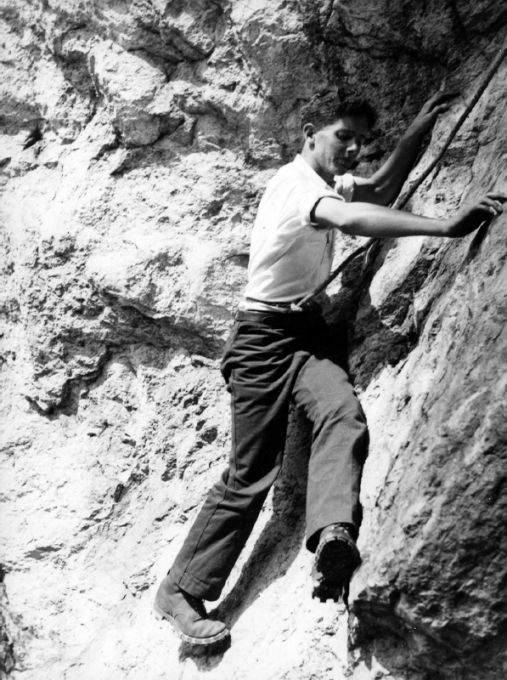

37Brower’s most important climb came in 1939, when he and three other Sierra Club climbers were the first to get to the top of Shiprock (

figure 2). At the time, mountaineers had labeled this 1,500-foot-tall rocky pinnacle “impregnable.” Because of a story in the July 22, 1939,

Saturday Evening Post, it was also the one summit many wanted to climb. The

Post had reported on the most recent failure to get up the middle and highest of the three towers.

38 Together, rising abruptly out of the New Mexico desert, the towers resemble a nineteenth-century schooner. The Sierra Club crew that arrived there in October 1939 consisted of Brower, Bestor Robinson as leader, Raffi Bedayan, and John Dyer. They gave themselves five days to mount Shiprock. All four of them would be needed for a successful climb.

Brower began climbing in the Sierra Nevada when he was twenty-one years old, and he joined the Sierra Club to hone his climbing skills. He became a “peak bagger” intent on capturing as many first ascents as possible, including Shiprock in New Mexico. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

The most recent climbers had tried to reach the middle tower by beginning with the north tower, and so did the Sierra Club climbers. But when they reached the place where the others had failed, Brower and his colleagues had a new weapon. Along with the usual supply of ropes, pitons, and carabiners, they brought expansion bolts and stellite-tipped rock drills. It is not clear if they used the drills, but Brower described how the climbers spent up to half an hour pounding in the supports for the expansion bolts. Robinson was clearly sensitive and expected criticism from the greater climbing community for the expansion bolts, which few climbers had used. Their value was that they could be used in wider cracks, too large to hold pitons. Robinson wrote, “We agreed with mountaineering moralists that climbing by the use of expansion bolts was taboo. We did believe, however, that safety knew no restrictive rules” and that if the bolts prevented a fall, their use was justified. When the climbing team reached particularly tricky overhangs, they would pound in three or even four pitons just in case one or two were to let go. They spent the final night up in the rock, the four men crowded into a two-person tent, and scrambled to the top the next morning. At the summit, Brower did not feel the usual surge of elation. For him, the climax had been solving the puzzle during the ascent, not what was on top.

The Shiprock climb brought national attention after the

Saturday Evening Post published Brower’s account of the climb and color photographs in its February 4, 1940, issue. The $500 check he was paid for the account was appreciated, but so was the note Robinson received from Robert Underhill, who eight years earlier had helped spur what was now being called a golden age of climbing for the Sierra Club. Underhill called the Shiprock climb the “finest thing done in rock-climbing on our continent.”

39Brower savored the recognition. He had come a long way from the eight-year-old who in Yosemite was too afraid to cross a log bridge over the Merced River and too timid to hike to Sentinel Dome.