We do not inherit the Earth from our fathers, we are borrowing it from our children.

DAVID BROWER, LET THE MOUNTAINS TALK, LET THE RIVERS RUN

The mountains had offered David Brower a lifeline, a way to boost his confidence and to escape from a difficult childhood. It was mountain climbing that led him to the Sierra Club. His admission into what was still a very elite, privileged club would allow Brower, the college dropout, into the salons of the wealthy and influential. The lawyers, doctors, and businesspeople he met at the Sierra Club would offer him new opportunities. He certainly earned their respect, both for his skill on the mountaintops and for his willingness to toil tirelessly for a pittance on behalf of the club and its causes. But his membership in the club was a sinecure, a lucky one, that came just at the right moment and would allow him to become an academic editor, an army officer, and eventually an environmental leader on a national and then international stage. And more than once the closest friendships that he had made through the Sierra Club would aid him at a critical moment.

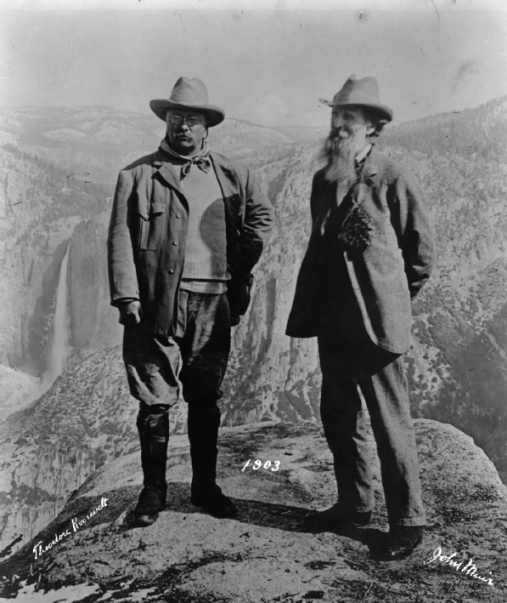

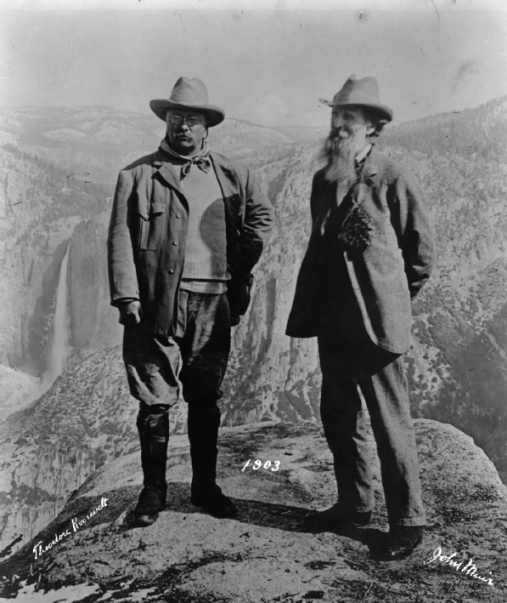

Brower joined the club in 1933. The organization in those days was very different from what John Muir must have envisioned when he helped found it in 1892 (

figure 3). Muir was a radical conservationist nearly a century ahead of his contemporaries. But the Sierra Club by the 1930s had become comfortably establishment and conservative. Its hallmark was leading summer outings, not crusading for nature. It was cozy and insular, with the emphasis on the word “club” in its name. The organization was broken up into chapters, and entry could be challenging. Applicants needed recommendations from at least two members to join. They sometimes had to appear in person and face sharp questioning. They might be asked to describe their experience in the mountains or elaborate on whether they would attend and run social events for the club. For years, some chapters also insisted that members be white. The Los Angeles chapter was especially notorious for its racial politics, and in 1945 its policy so angered Ansel Adams that he proposed at a board of directors meeting that the chapter be abolished. He failed to get a second to his motion. In the 1950s, many chapters instituted loyalty oaths.

1

John Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892 to promote the preservation of wilderness. While president, Theodore Roosevelt met Muir and was instrumental in setting aside millions of acres of wilderness under the care of the National Park Service. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Members elected their leaders, including the president, who headed the board of directors, but there was no campaigning. Muir was president for twenty-two years until he died in 1914. The charter membership was composed of professors and administrators from the University of California and Stanford University as well as some professionals and businesspeople. Muir’s reign was peaceful until he took on the proposed Hetch Hetchy dam project. Muir called the plans for the dam within Yosemite National Park a sacrilege, but many club members were businesspeople with ties to the dam’s developer, the city of San Francisco.

2 The schism within the Sierra Club over this issue was great, and after Muir lost the Hetch Hetchy battle, his successors were more cautious. “The attitude in the ’20s and ’30s was one of almost total ignorance,” said Brower. “Whatever lessons John Muir had provided to the board of the directors of the Sierra Club had been totally forgotten by the late ’20s.”

3The club was run by a handful of men: Joseph LeConte, whose influential family would erect a lodge in his honor that is still in use at Yosemite; Francis Farquhar, the scholarly patrician who edited the

Sierra Club Bulletin for years; and especially William Colby. As a young lawyer, Colby had been the assistant to a man considered the nation’s greatest authority on mining laws, Judge Curtis Lindley. Colby succeeded Lindley, acquired his influence, and fattened on retainers from virtually every major mining company in the West. The same pattern followed between the young Colby and the older Muir. “He fell in love with Muir almost as a God; he worshipped him,” said Richard Leonard. “He devoted huge amounts of time to Muir and the Sierra Club.” Once Muir was gone, Colby, Farquhar, and LeConte would trade the presidency or farm it out to others, with the tacit understanding that Colby was in charge. He would sit on the board of directors for forty-nine years and serve as its secretary for forty-four. Until age caught up with Colby at the end of World War II, the Sierra Club was his.

4 The club’s reputation as a conservative institution was so great that it persisted for years after Colby’s power waned. Edgar Wayburn, who would become one of the Sierra Club’s most prominent leaders in the second half of the twentieth century, once asked a San Francisco–based lawyer with a strong interest in the environment why he never joined the Sierra Club. “Oh, I’ve been anti-establishment,” he replied, “and the Sierra Club was too much establishment for me.”

5Brower joined the club to find climbing companions, but he also discovered camaraderie and conviviality. It was the Depression, so work came fitfully, and he spent much of his time volunteering for the club. He began by cataloging maps and recording first ascents and other accomplishments, and then he moved on to writing and editing the club’s monthly publication, the

Sierra Club Bulletin. Farquhar heavily edited Brower’s first submissions, but he encouraged Brower. In 1935, Brower joined the

Bulletin’

s editorial board. With Farquhar’s oversight, Brower began editing copy and working with authors and printers. Farquhar was demanding, but Brower responded well and learned quickly.

6In 1935, Brower found a job at Yosemite National Park, and he came under the influence of Ansel Adams. The Curry Company, which had been operating as Yosemite’s concessionaire since the nineteenth century, hired him to do accounting, but in a few months, with Adams’s assistance, the company offered him a post doing publicity.

Yosemite in the 1930s was significantly different than it is today. The National Park Service now tries to limit human impact in its parks. In the 1930s, Yosemite Valley was a small town with hotels, restaurants, swimming pools, stores, golf and tennis courts, and other special amusements to lure visitors. One of the big attractions at night was discarding garbage at the local dump, which essentially meant feeding the bears. It drew a big crowd. Another was firefall, a nightly event featuring a large bundle of live embers and burning logs thrown over the side of the cliffs of Granite Point. Firefall had begun decades earlier, and the 9:00

P.M. event could be seen across the valley because the descent was about 900 feet. In those days, the National Park Service played a secondary role to the concessionaire, Curry.

7 Brower’s job was to make the park desirable by taking photos, writing press releases, and designing brochures touting the park’s lures. He was good at it, although in later years he would express embarrassment about his huckster role.

8One reason Brower flourished was Adams, who was already becoming one of the great photographers of the twentieth century. The two men had much in common. Although Adams was ten years older than Brower, both had been raised in the Bay Area; both had spent summers in their twenties in Yosemite and the Sierra; and both played the piano—Brower was adept, Adams a master. Adams spent years training to be a professional musician and did not give it up until 1930, when he was twenty-eight years old. He was lured away by photography and the Yosemite Valley. He first visited Yosemite when he was twelve, got his first full-time job at seventeen when he managed the Sierra Club’s LeConte Memorial Lodge for the summer, and met and married Virginia Best, who lived in the valley. Together they made their first home in Yosemite, running the Best Studio, which her parents had established. His photography career flourished after he met Albert Bender, a San Francisco art patron in 1926, who promoted Adams’s work. By 1935, when Brower went to work in Yosemite, Adams was exhibiting and collaborating with such elite artists, photographers, and promoters as Alfred Steiglitz, Georgia O’Keeffe, Dorothea Lange, and Edward Weston. Yet the artistic commissions that Adams garnered needed to be offset by commercial assignments from such clients as Bank of America, Kennecott Copper Corporation, U.S. Potash, and the Curry Company. For a man who loved the wilderness and had a strong environmental conscience, it was not always easy to work with such clients. Adams shared Brower’s devotion to the Sierra Club, generously giving the club and the

Bulletin free use of his photographs. In 1934, Adams was elected to the board of directors. It would finally take a heart attack to get him off the board in 1971.

9Brower spent hours with Adams in the photographer’s darkroom learning lessons on photography. When they tired of that, Adams would talk about Yosemite and the true meaning of a national park. Adams disliked Curry’s commercialism and its carnival approach to Yosemite. He wanted nature preserved for nature’s sake, and he tried to convey that through his words and his artist’s eye. “He led me to seeing what was behind and within a photograph—his, not mine, and what could happen when words and photographs work their magic together,” Brower said.

10 When Brower was not in the darkroom, he might be in Adams’s gallery or house. The gallery was split level, with items to buy on the lower level and a row of Adams prints on the upper. There was also a Steinway piano. “When Ansel played the Steinway you almost regretted he had long ago decided to give up the concert stage for the lens,” said Brower. Brower saw him play the piano with an orange and do a bump, bump, bump of the “Blue Danube,” rising from the bench, turning, and playing the chords with his rear end. Michael Adams, Ansel’s son, remembered that Brower was often at the family home and that his father sometimes used Brower as a model. “He was part of the family,” said Michael.

11Despite Brower’s disclaimers about his role as a Yosemite publicist, it may have been the best job he had during the 1930s, and it lasted only eighteen months. The job was eliminated; his photography assignments went to Adams, and another man was brought in to write copy. The decade would be filled with these short-term positions interspersed by summer journeys into the mountains to hike or climb. No one questioned Brower’s conscientiousness or his ability; he just had other interests. His bosses at Curry offered him a job the next summer as a ticket seller and guide in their touring cars that shuttled guests around the park. A Hollywood film company hired him to do publicity film work for Curry in Yosemite.

12 It was great training for his future tasks as the Sierra Club’s executive director. Then Adams proposed that the Sierra Club hire Brower as an executive secretary to handle various administrative tasks. At this time, the club had only a part-time secretary. The board considered but did not accept the proposal. Instead, in 1938 Farquhar made Brower associate editor of the

Sierra Club Bulletin, thus significantly increasing his workload.

13 The club also agreed to hire Brower part-time, and from 1939 to 1941 he ran outings in the mountains and produced a film for the campaign to make the Kings Canyon area a national park. By 1941, he was so well known throughout the Sierra Club that he was elected to the board of directors.

14 And yet he was now approaching thirty, and although he loved climbing mountains, it would not pay the bills. He had had a string of jobs that led nowhere, he was single, and he was living at home. His situation did not look good.

And then, through the Sierra Club, a more tangible opportunity was offered. In spring 1941, Farquhar told Brower that his brother Samuel, who ran the University of California Press, had an opening for an editorial position. He urged Brower to apply. With Francis Farquhar’s backing, Brower met Samuel Farquhar and Harold Small, the editor. They hired him.

He was to share an office with Small’s editorial assistant, Anne Hus. The relationship did not begin well. She showed him around the office on his first day, introducing him. She seemed cold, perhaps resentful. He suspected that she was miffed. He had less experience than she did, yet because he was a man, he was going to be paid more. Plus, she had to give up half of her office to him.

15That is how it began, with exchanges in their office that were brief and businesslike. Over time, Brower began to learn more about Anne, and the relationship blossomed. He discovered that Anne had been born in Oakland and raised in a family that encountered some of the same troubles, at least financially, as Brower’s. Her father had emigrated from Germany, worked as a dentist, could speak four languages, and was an amateur musician. Then, despite having a wife and two children (Anne’s brother, Francis, was seven years older), he suddenly abandoned dentistry for more speculative get-rich schemes. Those schemes failed, the Depression arrived, the family struggled, and eventually they moved in with Anne’s maternal grandparents. By the time she graduated from high school, she needed to take a secretarial job with Farquhar at the press to be able to take classes at the university part-time. It took her thirteen years to earn her English degree, and by the time she met Brower she had finally advanced to editorial assistant.

16To break the ice, Brower teased her. The story most often told in the family was about the time Anne was working on a particularly difficult manuscript overloaded with footnotes. While she was at lunch, Brower typed out a page that mimicked the style of the manuscript, complete with ridiculous footnotes and an increasingly ludicrous text. She was halfway through the page before she understood the stunt and laughed in delight. However, she forgot to remove the page when she sent the manuscript back to the author. He was not pleased and complained to Farquhar and Small. They liked the joke and sided with Anne.

17 At the time, she had a beau, Paul Gordon, who had given her a small wooden duck that sat on her desk. When Anne was present but others were not, Brower would shoot the duck with a rubber band. The duck would fly into the next office. He was encouraged each time she laughed. But he could not seem to compete with Paul, who, like Anne, had an English degree. He envied how Anne and Paul could get into deep conversations about English literature.

18Brower had never had a serious relationship with a woman. He had had a crush on Betty Hillier when he was eighteen years old and working at a summer camp in the mountains. He sometimes dated Charlotte Mauk, and it was clear to some that Charlotte was in love with Brower. But he never returned that affection. Was it because she was less than a beauty or something else? Shyness? Discomfort? “I don’t think Dave was ever comfortable with women,” said Patricia Sarr, who worked with Brower years later and considered him only as her boss. He seemed to “radiate discomfort” around women, including herself.

19The courtship of David Brower and Anne’ Hus would be as unusual as their fifty-seven-year marriage. They never really dated before the wedding. She did take him to lunch for his birthday, and a couple of times they had sherry at her parents’ house. By now, the war was under way, and on October 12, 1942, Brower left Berkeley and his post at the press to join the army. He called Anne to say good-bye, and they exchanged a few letters. Then in December, he received a card from her. She had drawn a traffic signal with a green light. The message: Paul was gone, she was available. He sent daily letters to her and eventually one that included a marriage proposal. “Since I had never kissed him, it seemed a little abrupt,” she joked years later. But she accepted. “We went to our first movie when we had been married two weeks,” she added. “That was our first date. So I married a total stranger, actually.”

20They were married on May 1, 1943 (

figure 4). The Sierra Club board of directors was to meet that afternoon, and the timing of the wedding became precariously difficult because so many of the guests—including the groom—had to attend the meeting. It was unclear when the meeting would end so that the ceremony could commence. For a wedding gift, Brower gave his bride a membership in the Sierra Club.

21Brower met Anne Hus when they were book editors at the University of California Press. He did not begin to court her until after he went to basic training in the army in October 1942. They married on May 1, 1943, a union that lasted fifty-seven years and produced four children. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, and the Brower family)

After Pearl Harbor, Brower had one goal—to be an army officer and use his mountaineering and skiing experience. Army recruiters told him that being an officer was impossible for him because he did not have a college degree. But what he did have was Dick Leonard and the Sierra Club.

Two of his Sierra Club hiking companions, Dick Leonard and Bestor Robinson, had gone into the army in 1941 to help prepare mountain troops. When Brower appealed for help, Leonard wrote letters of support and even intervened to counter orders that would have meant Brower’s expertise was not used. Leonard helped him become and remain an officer in the Tenth Mountain Division, which has been called the most unusual unit in U.S. military history (

figure 5). The National Ski Patrol proposed the Tenth shortly before the war and recruited many of its members. Recruits were required to supply three letters of recommendation on their moral standing and skiing ability.

22 Brower applied and then waited as the spring of 1942 turned to summer, growing increasingly frustrated. Leonard’s letters were crucial, and the delays actually served as a blessing. By the time Brower went to basic training, the Camp Hale base in Colorado was teeming with old hiking buddies from the Sierra Club and elsewhere. He impressed the brass. Soon he was doing basic training in the morning and avoiding other tasks ranging from 15-mile marches to KP duty. Instead, he was assigned to write a new mountaineering manual for the army. He proved so invaluable for his writing and editorial skills that at one point he worried whether he would be allowed to go to Georgia for officer training. But he did. By the time he left Georgia as a second lieutenant, he had just enough time to return to California in late April, get married on May 1, and drive Anne on their honeymoon trip to Denver before he had to return to duty. They found a small apartment for her in Denver, and he returned to nearby Camp Hale to begin his duties now leading troops. Brower later transferred to the Seneca Rock Assault Climbing School in West Virginia. Anne then found a job in the historical G-2 division at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., where she handled soldiers’ journals direct from the fields of combat—bloody reminders of where her husband was headed. Her task was to write histories of the war as it continued.

23

During World War II, Brower served in the Tenth Mountain Division of the U.S. Army, working as a mountain-climbing trainer first in Colorado and later in West Virginia. He was overseas in Italy and returning home when the United States detonated two atomic bombs, and Japan surrendered. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

In both Colorado and West Virginia, Brower prepared troops for winter in high elevations, including teaching classes and training up in the mountains. Many troops and officers were unprepared for winter duty in the mountains. Many were from the Plains or the South, and most officers had little or no training in skiing or climbing or experience in harsh winter climates. Those officers did not understand that at higher elevations, packs and marches needed to be reduced to avoid exhaustion. One early two-week training session was especially notorious after temperatures fell to −25°F, and the result was a troublingly high number of cases of frostbite and pneumonia. By the time Brower and other veteran climbers took over, they included both enlisted men and officers in the training, some of whom outranked the trainers. One week would be spent in classrooms and another in the mountains, and the latter sessions could be especially brutal.

It was apparently some time during this period that Brower began having sexual relations with other men. There are no details about the liaisons, only Brower’s rare accounts to others that this is when he first began to have bisexual relations.

24 Brower’s discovery of his sexual interests in other men would not have been unusual at that time; some historians have suggested that World War II disrupted traditional gender patterns, moving young men out of traditional families into sex-segregated barracks and thus opening opportunities that many closeted gay and bisexual men had never considered possible for them before this point.

25In 1944, the army closed the West Virginia program and reassigned Brower to Texas, where his talents were of dubious value. Leonard again intervened and had Brower assigned as an intelligence officer with the Tenth Mountain.

26 Rumors were that the unit was going to Burma, and they were issued summer clothing. They instead landed in Naples, arriving just before Christmas for the final assault to push the Germans out of Italy.

27In Europe, Brower was often near or in combat zones. Outside Florence, he watched as waves of German aircraft crossed the skies that were streaked with tracers and high-altitude explosions from antiaircraft fire. In February 1945, he was in the Apennines atop a hill when a shell passed overhead, narrowly missing a tree and detonating. It was his closet brush to death in the war. In late April, he was on Lake Garda, at the base of the Alps, and witnessed fierce fighting between the Tenth and the entrenched Germans. On May 2 at 5:00

P.M., Brower was in San Alessandro when the phone rang, and Captain Everett Bailey answered. Bailey asked to have the message repeated. Then he smiled, grabbed Brower’s arm, and exclaimed, “Dave, the war in Italy is over.”

28In August, Brower and the Tenth were on transport ships on the Atlantic, back to the United States. They understood that any leave there would be short. The Tenth Mountain Division would soon head to the Pacific, for what was anticipated to be a deadly, brutal assault on Japan. One day before they were to arrive in Virginia, they learned about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. On August 14, 1945, when Japan surrendered, Dave and Anne Brower went dancing at the storied white-turreted Claremont Hotel in the Oakland foothills.

29Discharged, Brower returned to the University of California Press, where he was promoted from editorial assistant at $2,100 a year to editor at $2,760.

30 By now, Brower was a good editor, willing to suggest numerous changes to a manuscript when he felt it was necessary. He was weaker on the more technical aspects of publishing, especially in the pressroom. Samuel Farquhar died in 1949, and August Fruge took over. At one point, Fruge made Brower responsible for overseeing the printing of the press’s books. However, his inexperience became a problem, and he had to be taken off of that assignment.

31The biggest changes for Brower in this period were his marriage and, soon, his new status as a father. Kenneth had arrived in 1944; he was followed by Robert in 1946, Barbara in 1950, and John in 1952. This growing family needed a place to live, and Brower found an empty lot on Stevenson Avenue in the Berkeley hills, with a view of the bay. The two-bedroom house was finished in 1947; it would soon need two more bedrooms. Anne chose not to stay at the press, although she would remain an editor of both her husband’s and others’ work.

32For Brower, even more important than the job or the family was his return to the Sierra Club. It meant less mountain climbing and more toil to save the mountains. Seeing Europe had changed him. Brower’s environmental ethos had been slow to develop. He had originally joined the club to hike and climb mountains, not to change the world. But he had listened to Adams’s conservation messages; he had read Muir, Thoreau, and others; and he had seen firsthand in Europe how humans could spoil wilderness. It had been one thing to appreciate the wilds of California’s Sierra Nevada, another to contrast that mountain range with the Alps of Italy, Switzerland, and Austria. In an article written in 1945 for the

Sierra Club Bulletin, he described seeing wild places, precipices, mountain torrents, glaciers, and forests ravaged by a conqueror. The culprits were too many people and too much development. “The wilderness,” he concluded, “died of over dosage” in Europe.

33The beauty of the wild needed to be protected, he was realizing, a viewpoint that others, including Leonard and Adams, shared. This group of what was being called the “young Turks” began to challenge the old guard made up of Colby and his brethren. One of the early battles dealt with roads. For decades, road builders had had carte blanche to go wherever they wanted, including the Sierra range on every available pass, with the full support of the Sierra Club. In 1949, Brower and another prominent Sierra Club member, Harold Bradley, wrote a seminal article on the hazards of road building in the mountains. They picked out Yosemite as their prime example. Access to the valley had inalterably changed it from a national treasure to a recreational resort, they complained. Instead of concentrating on the sheer granite cliffs and lacy cascades of the waterfalls, too many people went there for the swimming, tennis, dining, and dancing.

34 The article was noteworthy because it was here that Brower began laying the foundation for an environmental creed that would grow over the next twenty years.

How tensile that conviction could be was tested around the same time. The National Park Service wanted to build a road into the new Kings Canyon National Park. Ten years earlier Colby had asked powerful political and business forces in the nearby San Joaquin Valley to support creating the new park. In return, he promised that easy access would be provided to get there, potentially opening up new trade for local business. After the park was created, however, the road was delayed by the war. Once the war was over, the new road design plans unveiled in the late 1940s startled Leonard, Brower, and others. The road was wider, more developed, and penetrated deeper into the forest than they had anticipated. But Colby was adamant that it had to be built, that he would not back down on his promise. And Colby prevailed.

35It was one of his last victories. Colby still cared, but he was weary, and he had trouble leading. He would come to a board meeting, make a fiery speech, and then, as the meeting settled, fall asleep.

36 In 1949, Colby and his allies relinquished control of the board presidency, allowing it to go to Lewis Clark, a close friend and confidant of Leonard’s. Four years later Leonard was president. This new leadership was going to be different—still willing to work with government and industry but also far more willing to question, to criticize, and perhaps even to embarrass the other side when necessary. It was that willingness that led the club to take on the Dinosaur fight.

The army had made Brower an officer and thus began the process of making him a leader; now the Sierra Club and the mountains would complete that task. In 1947, the Sierra Club asked Brower to become responsible for its esteemed high trips. It was quite an honor. Muir had first asked Colby to organize a series of trips into the mountains. He wanted to document that the mountains were being used recreationally and to build support for conservation by making members experience it. Colby had developed these high trips, which could last two, four, or even six weeks. Hikers were limited to forty pounds of gear, which was carried by mules along with all of the food and stock required by the commissary staff. Camp would be established for three or four days, and then the hikers, staff, and mules would move on to another site.

37Campers would be awakened by 4:30

A.M. by the cooks calling, “Everybody get up, get up, get up, get up.” Some might take a dip in an icy stream, and everyone lined up for breakfast before they were off on the trails, supplied with box lunches.

38 One of Colby’s duties, or pleasures, was setting the pace on hikes. The tramps were swift and measured by what was called a “Colby Mile.” Hikers on high-trip treks with Brower soon named his measurements “Brower Miles” because of Brower’s pace. Early on Brower brought his two oldest sons, Ken and Robert, on these trips. Ken would start the hike with his father, but he could rarely keep up. He soon found that older hikers had the same handicap. “He could really do it down the trail,” said Ken. “Everyone of his generation said nobody could keep up with him.” The name “Brower Miles” also stuck because it often seemed that the distance traveled was far longer than what Brower had advertised. “The Brower Mile may have been a white lie to keep up the spirits of his flock, or it may simply have been cardiovascular,” said Ken Brower.

39Back at camp, after dinner came the campfires, the daily highlight of the high trip. The campfire was a time to make announcements, sing, tell stories, skits, and give sermons. Colby was always asked one night on each trip to talk about Muir, and that usually led to discussions about the need to preserve the wilderness surrounding them. It was here, around the campfire, that Brower’s reputation for oratory was created, honed, and perfected. Brower had been helping with the high trips since 1939, and that was when he was first asked to speak at the campfires. He had no experience in public speaking. By nature, he was shy. Yet around these campfires Brower discovered his speaker’s voice, the excitement and charisma that would charm audiences for decades to come. “He had a talent for influencing people,” said Lewis Clark. “He had a great repertoire of songs. He used to take his accordion along, give performances at the campfire and entertain people and inspire them” (

figure 6).

40

Brower became an accomplished performer as he spoke and played music on many camping trips organized by the Sierra Club. For years, he led Sierra Club expeditions in California’s Sierra Nevada and beyond, including Dinosaur National Monument on the Colorado–Utah border. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Young Ken Brower would sit on the edges of the campfire and watch the audience watching his father. “For the first time, I sensed his way with words and the power of his presentation,” he said. “And everyone in that circle of the campfire was moved by what he said.” By the time his father was deep into the battle to save Dinosaur, he had become a master of public speaking not just at a campfire but in the halls of Congress. Ken Brower remembered that one time when he was about eight years old and was going to breakfast the morning after his father had given one of these campfire talks, a woman stopped him and exclaimed, “You do realize, don’t you, that your father is a great man?”

41“He was heroic,”

said Phillip Berry, who went on his first high trip in 1950 when he was thirteen. To the young teenager, it seemed that Brower had accomplished more than anyone else he had met. “When he said he liked climbing, it was real. When he ate the fish that you brought him, he genuinely enjoyed it and thanked you. He could climb higher, hike faster, sing as well as anyone and play the accordion, the only musical instrument that made sense in the mountains.” He even looked the part in his mountaineer pants with the many pockets.

42Then in the summer of 1952 everything that Brower had worked for was threatened. He reportedly made sexual advances to a man at the Hearst Gymnasium on the University of California campus. The man not only resisted but also complained to the administration. University officials apparently told the head of the press, August Fruge, to fire Brower.

The most detailed but also probably the most biased account of this situation came from Richard Sill, then a physics professor at the University of Nevada at Reno, who was a Sierra Club board member in the 1960s and 1970s. Sixteen years after the complaint was made, in 1968, Sill made a series of accusations against Brower on why he should be fired as the Sierra Club’s executive director, and among them was this statement: “Dave was discharged in an oblique fashion from the University of California for homosexual attacks on a young negro in the Hurst [

sic] Gymnasium. Dave fought the charge; he was able to keep his job until the end of the contract year, and they did not discharge him in a formal sense; they merely saw to it that no money was available for him to be rehired.”

43Fruge confirmed in his oral history that Brower was in trouble in 1952 and needed a new job. “There was no future for him” at the University of California Press, said Fruge. He would not explain further. Jeffrey Ingram, who worked for Brower, reported many years later that his boss had told him he had gotten into trouble at the campus for making a pass at another man.

44Fortunately for Brower, it was around the same time, according to Fruge, that Richard Leonard told him that the Sierra Club was interested in hiring him and had wondered about his availability. Virginia Ferguson, the part-time secretary for the Sierra Club, overwhelmed by the demands of the club membership, which now numbered seven thousand, had told Leonard she needed help. Fruge wondered later if Brower talked to Leonard about his situation. Board member Lewis Clark remembered Leonard telling him, “I think we can get Dave as our executive secretary.” Brower, however, wanted the title

executive director, a position that went far beyond that of executive secretary, and the idea gathered momentum. The board approved the appointment on December 15, 1952. Club president Harold Crowe announced it in the January 1953 issue of the

Sierra Club Bulletin. Crowe said that the idea for the position recently became “both necessary and practical.” He did not explain what he meant.

45If Leonard, Crowe, and other board members, including Ansel Adams, knew about the incident that had precipitated the University of California Press to force Brower out, they did not talk about it. Nothing positive could be said at the time. Homosexuality in the 1950s (and for years after that) was labeled a perversion in the United States. The Eisenhower administration prohibited the hiring of gay men or women by the federal government or contractors. The Federal Bureau of Investigation spied on the meetings of gay organizations. The U.S. Postal Service traced the mail of those suspected of homosexuality and sometimes passed on evidence to the individual’s employer. Vice squads invaded homes and entrapped homosexuals in public places. It was a witch hunt, and the Sierra Club would gain nothing if it became publicly known that its new executive director had sex with men.

46Ingram, whom Brower had hired to work for the Sierra Club in the late 1960s, had a number of conversations with Brower on this issue, and he is convinced that at least some members of the board had to know. He believed it was a situation in which the friendships Brower had developed over the years overrode any fears of the consequences of America’s homophobic culture. “To me it was an example of the old-boy network where everyone looks out for everyone else,” said Ingram.

47If so, the decision was an act of both courage and friendship by men such as Leonard and Adams. They believed that Brower had the ability to be a good steward, to manage the outings program, to take care of the financial books, and to assist in conservation campaigns. They would come to realize that they had seriously underestimated Brower and his vision. For the next few years especially, though he would vex and frustrate them at times, they would not be sorry they had selected him to lead the Sierra Club.