Conservationists have to win again and again and again. The enemy only has to win once. We are not out for ourselves. We can’t win. We can only get a stay of execution. That is the best we can hope for.

DAVID BROWER, IN JOHN McPHEE, ENCOUNTERS WITH THE ARCHDRUID

In March 1956, David Brower was in Washington, D.C., about to accomplish the greatest victory so far in his career. He would also consider it his greatest defeat.

The triumph was Dinosaur. After years of fighting, dam builders had agreed to capitulate and not erect dams at Echo Park and Split Mountain within the Dinosaur National Monument. They instead accepted Brower’s compromise to build a higher dam downstream on the Colorado in Utah’s Glen Canyon.

For as long as he lived, Brower regretted not fighting harder to prevent the Glen Canyon Dam, which began holding back the Colorado River in 1963. In the foreword to the book

The Place No One Knew: Glen Canyon on the Colorado, by Eliot Porter, he wrote: “Glen Canyon died in 1963 and I was partly responsible for its needless death. So were you. Neither you nor I, nor anyone else, knew it well enough to insist that at all costs it should endure. When we began to find out, it was too late.”

1He traced the failure back to his decision in March 1956 not to oppose legislation authorizing the dam. “My horrible mistake at that time was to have stayed in Washington,” said Brower, “instead of to have grabbed the next plane back and called for an emergency meeting of the Executive Committee or the Sierra Club board to argue why we should have stayed in the battle and stopped the whole thing.”

2 Compromise with his enemies, consultation with his friends, these were the hallmarks of Brower’s Sierra Club administration in the 1950s. Working with allies, he was building the Sierra Club into a national force. His name was taking on meaning, and as the Sierra Club grew, so did Brower’s organizing leadership of the loose confederation of environmental groups. But winning at Echo Park in 1956 by compromising over and losing Glen Canyon in the same year would change him. He would conclude that the policies of compromise and consultation were a mistake. No more would he compromise if it meant losing a unique natural resource. No more would he be bound by anyone who would settle, even if it meant breaking longstanding friendships. Mike McCloskey, who came to the Sierra Club in 1961, saw Brower change. “One reason I realized that he became so disillusioned with compromise was during the ’50s he made a lot of them,” said McCloskey.

3The fight to oppose the two dams in Dinosaur had already been under way for several years when Brower demonstrated in January 1954 the flaws in the Bureau of Reclamation’s math on evaporation. It would take two more years to kill the project, and Brower worked tirelessly to accomplish that aim. The Sierra Club planned another series of rafting trips down the rivers in Dinosaur in the summer of 1954, and the publicity would draw more than seventy thousand visitors for a visit to the national monument.

4Brower also commissioned a second film and a book on Dinosaur. The film, produced and narrated by Brower, was shot in a single day. Called

Two Yosemites, it countered the argument that a reservoir at Dinosaur would make the Green and the Yampa Rivers more accessible to more people. It described the beauty of Yosemite Valley and then showed how the rim around the reservoir at Hetch Hetchy had been denuded into a wasteland. Silt turned to dust that turned to scum in the water. “Where is the pulsating heartland of this place?” asked Brower, the narrator. “It is gone.” The film was only eleven minutes long, but it was effective and was distributed to groups throughout the country. In the summer of 1955, Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society set up a movie projector in the halls of Congress. “You’ve got to see what this does; it’s only eleven minutes,” he would announce to anyone who showed any interest. Passing lawmakers paused, intrigued by Brower’s scenes. Representative Gracie Pfost, who was from Idaho and sat on the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs and the Subcommittee on Irrigation and Reclamation, cried. Others did too.

5Brower convinced the famed Western writer Wallace Stegner to edit a book that would be titled

This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers and New York publisher Alfred Knopf to produce it. It was ninety-seven pages long, thirty-six of them consisting of spectacular photographs, many in color, with chapters from several authors, including Stegner. In the preface, Stegner wrote that the book’s contributors had not chosen “to make this book into a fighting document.”

6 Perhaps not, but that was certainly Brower’s intention. To make sure that everyone got the message, Brower tucked into the back of the book a photo of the ugly mud flats on the shore of Lake Mead. Its caption, a quotation from the Department of the Interior secretary Douglas McKay, read: “What We Have Done at Lake Mead Is What We Have in Mind for Dinosaur.”

Although Brower’s name is never mentioned in

This Is Dinosaur, it was clearly his creation. Said Brower, “I got all the contributors together, I got the photographs together, got the editor—worked with him in laying it out—and got the publisher.” It was a small print run, only five thousand copies, and the book was rushed to ensure that a copy was delivered to every member of Congress. No one had used a book as a political tool to save a pristine natural area. Brower pioneered the technique and would perfect it over the next fifteen years.

7By the spring of 1955, when the book was published, seemingly every major print media outlet was raising concerns about Dinosaur, including

Life,

Time,

Readers Digest,

Collier’s,

Saturday Evening Post,

Harper’s,

National Geographic,

Scientific Monthly,

New Republic, and

Sunset. Brower was sending information out to reporters and, as he described it, running up “enormous telephone bills.” He accompanied John Oakes, the senior editor at the

New York Times who wrote a conservation column, on a trip to Dinosaur. They spent days in a car traveling together, and Brower bragged that he knew more specific details about the Echo Park and Split Mountain dams than Reclamation’s engineers, including his nemesis on the evaporation issue, Cecil Jacobson. He later claimed often that during the trip, when Oakes asked a question, “Mr. Jacobson would turn to me for the answer. I had boned up on that; I knew more about the Colorado River than I ever want to know again, about anything. It was coming out of my ears.” The trip was successful; the

Times published an editorial opposing the dams.

8Although opposition to the dams was growing nationally, the pro-dam opinions in the Rocky Mountains remained firm, and a local public-relations campaign for that side was initiated. The supporters formally created the Upper Colorado River Grass Roots, Inc., but in their literature they called themselves the “Aqualantes.” They raised money, sent volleys of letters to local newspapers, ran newspaper ads, mailed flyers, distributed handbills, and produced their own film,

Birth of a Basin. The film was so bad that some dam opponents suggested making copies and distributing it to help their side.

9The Sierra Club launched its own letter-writing campaign, which was so effective that mail sent to the House of Representatives on the issue was running eighty to one against the Echo Park Dam. As early as winter 1954, President Eisenhower had sought in his State of the Union Address to reassure those with concerns about Echo Park.

10 The letters eventually had a boomerang effect, though—dam opponents began receiving propaganda from pro-dam forces. C. Edward Graves of the National Park Association said that a mailing list had apparently been leaked by someone in the Department of the Interior, a step he called “a decidedly unethical procedure.” The

Christian Science Monitor discovered that Senator Arthur Watkins of Utah had asked for the names from Interior officials, and he allegedly had passed the names on to others.

11Sierra Club board members were pleased with Brower. When they had hired him in December 1952, he was to work out of the Sierra Club offices in Mills Tower, the handsome, Romanesque-style edifice in San Francisco’s financial district. He did not spend much time there. His original responsibilities were to work on membership, run the summer outings, and carry out the club’s conservation priorities. He reversed the prioritization of these tasks, spending much of his time on Dinosaur and other conservation issues. When he was not on conservation trips, he was out each summer on outings. The club was looking beyond California for its trips, which now included rafting down the Green and Yampa Rivers in Colorado and Utah, hiking in the Pacific Northwest Cascades and the Tetons in Wyoming, and boating the Colorado River downstream in Utah and Arizona. There were now so many trips that Brower could not make them all, and sometimes he would meet a trip that was concluding for a day or two and then join a new one at the trailhead, again for only a day or two. Finally, in 1955 the board, concerned about Brower’s long absences from Mills Tower, reluctantly limited his time on outings to two weeks a year.

12Anne Brower and the children would travel with Brower to the trailheads. The two oldest, Ken and Robert, often hiked with their father, but the other two, Barbara and John, were simply too young. Anne Brower was a loyal wife throughout their marriage, but living with her husband was never easy. She once told an acquaintance that when Brower became executive director, she thought that finally he would use his leisure time for something else, such as spending more time with the family. Instead, he was traveling half the year, and being at home simply meant he was in the area. On the rare occasions that he arrived for a family dinner, phone calls often interrupted them. He worked virtually every weekend. The bottom line, she said, was that Brower’s work for the Sierra Club caused damage to the children and the marriage.

13Phil Berry, who was thirteen years old when he met Brower and knew him his entire life, said that much in Brower’s lifestyle was difficult for those who were closest to him, especially Anne. He began to elaborate and then stopped himself. “It was just sad,” he said, “it was just sad.”

14Despite the hardships, she stayed with Brower. She became an intellectual confidante and an adviser, and together they developed a synergy that renewed their strengths and their aspirations. Gayle Brower, a sister-in-law, said the relationship was difficult at times, but it was supportive to both husband and wife. “Anne helped form Dave, but at the same time Dave helped form Anne,” she said.

15Brower had been in the position of executive director for only two months when he made his first pilgrimage to the East Coast in February 1953. He attended the annual meeting of the Natural Resources Council (NRC) in Washington, D.C. The NRC was an unusual organization. It represented forty environmental organizations, from outdoor clubs to hunting and fishing organizations and professional societies such as the American Planning and Civic Organization and the American Society of Mammalogists. Its diversity was as much a hindrance as a benefit. It struggled to agree on anything. Yet it was a great forum for meeting people and sharing views.

16 At that first meeting, Brower was a bit player, almost overwhelmed by the size of the gathering, which drew 1,229 registrants and 870 participants to the banquet in 1953. At the behest of other conservation leaders, he sat in on meetings with Richard McArdle, who headed the U.S. Forest Service, and even had a private meeting with Conrad Wirth, director of the National Park Service. Brower had no audience, however, with Douglas McKay, the Oregon car dealer turned secretary of the interior.

17In a measure of how rapidly his stature was rising, two years later, in 1955, he was elected chairman of the NRC. This time he set up and ran a meeting with McKay. Sierra Club board member Bestor Robinson suggested that Brower not “embarrass” the interior secretary by asking him to reverse his stand on Dinosaur. The meeting was amicable, although McKay rambled at times and complained about distortions perpetuated by the Sierra Club. Brower did not argue with him, and they were able to work out a joint statement indicating that they were striving to work together.

18In New York and Boston, Brower attempted to curry favor with editors and writers. Carl Gustafson of the Council of Conservationists told Brower once that he did not know anyone in the conservation movement who spent so much time with the press. “This shocked me, for I have done so little,” observed Brower. In Boston, he talked books with Paul Brooks, an editor at Houghton Mifflin, and Brooks mentioned that he was working with Rachel Carson, who was writing a book that Brower would find interesting. In New York, Brower offered story ideas about Dinosaur to Raymond Moley, an influential columnist with

Newsweek; Jack Fischer, editor of

Harper’s; and Oakes of the

New York Times. In Washington, Brower persuaded Gilbert Grosvenor, president of the National Geographic Society, to let him write a long piece on the Sierra Club high trips for the magazine.

19In Washington, where the Sierra Club had no lobbyist or even a physical presence, Brower’s tasks were more political. He lobbied on Capitol Hill, going up and down corridors, reaching the people in power who affected conservation in the Eisenhower administration. After making two trips to the East, during which he had seventy different meetings, Brower reported that “the influence of the Sierra Club” was well represented.

20 When testimony was needed before Congress, Brower was usually the first on everyone’s list to represent the conservation side. He noticed that as time went on, his prepared statements kept getting longer and his time testifying also lengthened. During one hearing, he realized he was on the stand for two hours and fifty-seven minutes without a break. “Senators would go off to the library, back to their office,” he said. “They would switch around. They were questioning me quite hostilely for that whole period.” He said he did not mind. “It was fun to go after their economics,” he recalled. “They were really after an extremely crazy project,” the Echo Park Dam.

21On that first trip to Washington, he dined at the Cosmos Club, the Victorian mansion and club off DuPont Circle and tony Embassy Row, with the few other colleagues who worked full-time in the conservation movement. The Cosmos was to become Brower’s Washington home away from home, just like the Biltmore Hotel in New York City and the Parker House in Boston. Brower’s expense account was generous, and he went first class with airfare, hotels, and restaurants. He especially liked lunch. He never wanted to eat alone, and he preferred a dining party of no more than seven because too many diners produced too many discussions. He was the raconteur, the equinox, and, most important, the host at the vortex of each discussion (

figure 7). He selected the restaurant, preferably plush and opulent, with overstuffed leather upholstery and a full bar—a man’s place. On one occasion in the mid-1960s, several junior members of the staff and friends went with Brower to his favorite Manhattan restaurant for lunch. It was his birthday, and they celebrated. They wanted to pay the tab afterward, but Brower would not hear of it. The struggle over the bill, which had begun jokingly, quickly escalated as Brower became noticeably angry. Everyone let him pay the bill.

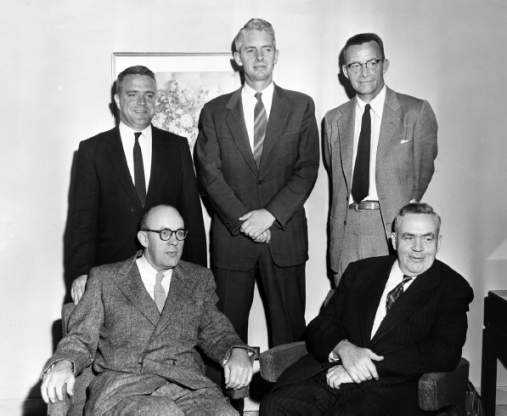

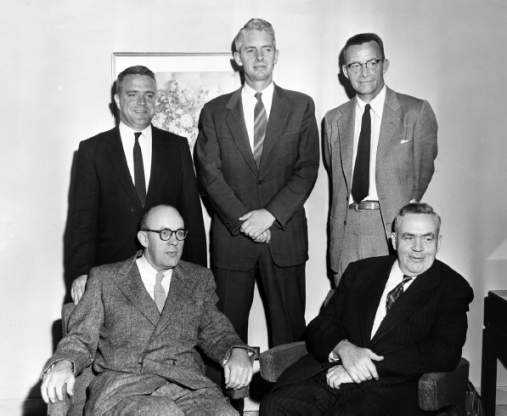

22

Five leaders of the conservation movement in the 1950s (counterclockwise from lower left): Howard Zahniser, Wilderness Society; Carl Gustafson, Conservation Council; Joseph Penfold, Izaak Walton League; David Brower, Sierra Club; and Ira Gabrielson, Wildlife Management Institute. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

Despite his success with the Bureau of Reclamation, the press, and the campaign, Brower throughout 1954 never felt that confident. In June 1954, he was back before the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, which was even more hostile than the House committee. In July, it approved a bill authorizing construction of the five dams by a vote of eleven to one. But it was clear that the issue was bogging down in both branches of Congress. Brower, speaking in August to the Associated Sportsmen of California, said, “We’ve forged together a team for ourselves that has worked together better than any other . . . in conservation history.”

23Brower decided that the Sierra Club needed to become stronger not only to fight the dam in Dinosaur but to tackle the inevitable clashes of the future. To make it stronger, he needed the support of the Sierra Club’s board of directors. In the fall of 1953, he began discussions with them, asking if they wanted the Sierra Club to be a national, regional, or local organization. A good mountaineer, he told them in a prepared statement, always knew when it was time to pause and check the course.

24 In response, board members agreed almost unanimously that the club needed to expand. Even Robinson, more prone to compromise than others, backed him. Only Francis Farquhar, a key member of the old guard, objected, expressing a view that he would hold for the rest of his life. The board agreed to expand, and it set in motion changes that would eliminate the strict membership requirements.

25At the time, the Sierra Club had ten chapters. Nine chapters were in California, and one had been created in New York in 1950, although the Atlantic chapter was designed to represent the entire East Coast.

26 Sierra Club members in the Pacific Northwest wanted to create a chapter, and Brower envisioned others throughout the United States. He played a key role in forcing the club to look outward. Until that night, it had been gliding, so Brower gave it direction. In assessing Brower and his achievements, Carl Pope, executive director of the Sierra Club from 1992 until 2010, believed that the changes Brower made to restructure the club marked his greatest accomplishment. He took what was a club, said Pope, and created an organization. “In the process, what he was doing in creating a new environmental organization was that he was helping create what became the environmental movement.”

27Brower was very much into consulting with the board and communicating exactly what he was doing, especially because he was out of the office so often. From 1953 to 1959, he typed long, detailed reports about his trips, some of them up to forty pages long.

28 What is most remarkable about these reports is Brower’s degree of detail. In a few years, however, Sierra Club Board presidents would claim that Brower rarely told them where he was traveling for the club.

Although some in the Sierra Club worried that Brower was too prone to criticize those who did not agree with him, he had very strong support overall in the early years of his tenure. In 1959, one of his longtime champions, Ansel Adams, wrote Harold Bradley, then the board’s president, and called Brower “the conservationist of the era” and “a creative genius.” Bradley agreed, but he worried that lack of sleep, the travel, and the inevitable frustrations of the work might wear down Brower. At times, he could be difficult to manage. He did not take criticism well, and he occasionally disobeyed orders, such as the time in 1957 he was told not to go to a meeting in Florida but did anyway.

29Brower still supported raising the height of the Glen Canyon Dam, although in October 1954 he wrote that the Bureau of Reclamation might be stupid enough to continue to oppose the higher dam and risk losing support for any dam at Glen Canyon.

30 By 1955, however, he had more doubts about Glen Canyon Dam. “I began to look at it with just an editor’s mind, not an engineer’s,” Brower said. “The main thing I found was that they were overdeveloping the entire river.”

31 He began suggesting that there were other alternatives to building more dams at Dinosaur, Glen Canyon, or anywhere. He argued that coal-powered electric generation was cheaper and could be built closer to power sources than hydropower. And, like many people of this era, he was optimistic that nuclear power within a few short years would be even more competitive. In a talk in 1955 to the Associated Sportsmen of California, he said, “We’re not asking anyone to stop using water, but merely not to store it where it floods dedicated lands, nor to store it for damaging hydro electrical installations that the atomic scientist, with his black magic, will in all probability render obsolete before they can pay for themselves.”

32The politics of water, especially Colorado River water, in the West could be colossally byzantine, often pitting California against everyone else in the region. Some began to suspect that the California-based Sierra Club was only a stalking horse for California’s water barons. In one hearing, Senator Watkins of Utah kept Brower on the stand for ninety minutes grilling him on the Sierra Club’s objectives. “What he was trying to do in any way he could was to prove that I was just the patsy of Southern California,” said Brower. It is true that Brower had joined forces with California’s water interests, especially their lawyer, Northcutt “Mike” Ely. “I’m not sure whether they approached us or I approached them,” recalled Brower. “We certainly saw that we were together. [Ely] was the man that Arthur Watkins was trying to say that I was in collusion with. Indeed we had meetings. We would join anyone who could help us save Dinosaur.”

33By late fall of 1955, the issue of the two Dinosaur dams had stalled in Congress. Flustered by the stand-off, governors, members of Congress, and other dam supporters agreed to meet in Denver on November 1, 1955, to consider their options. It was a critical meeting. But the conservationists trumped it by running a full-page advertisement in the

Denver Post on October 31. Five representatives of conservation organizations, including Brower, signed it, and Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. of Mallinckrodt Chemicals, a Sierra Club member, paid for it.

34 The wording in the ad was less important than its message, which the politicians understood immediately. The Dinosaur dam opponents were not going away, and they would oppose all of the dams in the Colorado River Storage Project. Further, they were in for the long term, no matter how long. Their stance was unacceptable to those who wanted the greater water project. The ad and the warning seemed to have an impact. The day after the ad ran, at the Denver meeting on November 1, a longtime supporter of the Dinosaur dams, Senator Clinton Anderson of New Mexico, announced that the Dinosaur dams must be removed from the bill. By the next day, a resolution was offered agreeing that two Dinosaur projects would not be reinserted into the legislation. As the parties milled around before casting votes in Denver, a longtime dam supporter began congratulating dam opponents. He explained that if they did not like the resolution that proposed removing the Dinosaur dams from the bill, they should offer their own version, and it would be approved.

35The battle was over. On December 2, Secretary McKay announced that the administration would abide by the wishes expressed in Denver. On March 28, 1956, Congress formally authorized the Colorado River Storage Project without the Dinosaur dams. Everyone had to wait almost two weeks for President Eisenhower to return from a trip to the Master’s golf tournament, but he finally signed the bill on April 11, 1956.

36By then, however, Brower was already having misgivings. Years later, he revealed that many congressional insiders told him in the days before the bill was passed that he and his forces “were out of their minds” in not opposing the entire upper-river project.

37 In the Senate, key leaders told him they now had the clout, with the Sierra Club’s support, to kill the entire project. Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois wanted to know why the Sierra Club had bailed out. On the day the House voted, Brower was sitting in the gallery and was spotted by Congressman Wayne Aspinall. Aspinall, a floor leader, approached Brower and asked about the Sierra Club’s plans. Brower told him the club had dropped its opposition, releasing a bloc of more than two hundred votes that had been opposed. Congressman Craig Hosmer, a longtime dam supporter from California, was amazed by the club’s new stand allowing Glen Canyon Dam to be built.

38Brower, the Sierra Club board, and other environmental organizations

had discussed the option of killing the Glen Canyon Dam. Brower had met with the board’s Executive Committee on December 27, 1955, and again with the full board on January 7, 1956. The price of peace, board members declared, was that Congress needed to agree that no dam would be built in a national park or monument.

39 Robinson recalled Brower arguing that the Glen Canyon Dam should not be built. “You see, he [Brower] was the purist who thought that it was important to take a purist stand even though you went down to defeat,” said Robinson. “And we were hinging our whole case on ‘go ahead and use Glen Canyon.’ ” Robinson felt that it was far more important to defend Dinosaur and downstream at the Grand Canyon than it was to protect Glen Canyon.

40 Leonard agreed. “Congress would have been convinced that the preservationists were unreasonable and were urging that the entire Colorado River be unused and just allowed to flood away into the Gulf of Mexico,” said Leonard. “That kind of argument would have been so strong that we would have had both Echo Park Dam and Glen Canyon Dam.”

41Both the Wilderness Society and the National Parks Association, the two other key opponents of the Dinosaur project, also struggled with this issue. Trustees for the Parks Association concluded that they did not want to be accused of “being excessive in [their] demands.” Zahniser at the Wilderness Society concurred.

42What is remarkable about these discussions is the volume of warnings that all these organizations had received up to this point. Historical records, a strong organized effort within Utah, and the advice from some of Brower’s closest associates extolled the beauty of Glen Canyon and urged that it be preserved. The Sierra Club even ran river trips through Glen Canyon before the dam was authorized, and at least some of those passengers afterward resolved to fight the dam. Alice Joy Keith of San Diego toured Glen Canyon on a river trip in the summer of 1955. “In the name of all that America means to us, I beg you to vote against the Glen Canyon Dam,” she wrote to 125 congressional representatives in February 1956. A copy of her letter went to Brower.

43Brower would call Glen Canyon “the Place No One Knew,” and there was certainly truth to that assessment. It was isolated, hundreds of miles from towns, highways, or railroads. The U.S. Geological Society listed the region as the most isolated in the continental forty-eight states. But John Wesley Powell had described the beauty of Glen Canyon, which he named for the verdant emerald groves that often shaded the river, when he took the first of his famous journeys down the Colorado in 1869.

44 In 1940, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes proposed making Glen Canyon part of the Escalante National Monument, which would have covered 280 miles of the Colorado River canyon lands. Utah politicians and merchants, however, saw this proposal as a land grab by the Park Service, and then the outbreak of World War II killed its prospects.

45Wallace Stegner; Charles Eggert, a filmmaker who worked with Brower; and Lewis Clark, a Sierra Club board member, all told Brower about Glen Canyon in the years before the March 1956 vote. At a June 20, 1954, board meeting, Clark described his journey through the canyon and argued that some of the most spectacular features would be destroyed by a dam. Board members agreed that they should try to preserve the region’s scenic values, but their effort would have to be coordinated with whatever Congress did.

46Stegner’s

warnings came during and after his work on the Dinosaur book. Stegner had grown up in Salt Lake City; he had explored the Utah wilds as a youth; and in 1948 he had published an account of his journey down the Colorado and through Glen Canyon in the

Atlantic Monthly. He described his first camp in the canyon as “almost unimaginably beautiful—a sandstone ledge below two arched caves, with clean cliffs soaring up below two arched caves, behind a long green sandbar across the river.” Nearby was a canyon that was commonplace in Glen “but that anywhere else would be a wonder.”

47Eggert wrote to Fred Packard of the National Parks Association in August 1955, exclaiming that the region contained “the most incredible works of Nature I have ever witnessed! I cannot think of the possibility of destroying such magnificent beauty.”

48Utahans mounted at least two concerted campaigns to oppose the Glen Canyon Dam, urging Congress to make Glen Canyon a national park. One effort was organized by a group of river guides, a second by a group of prominent Utah residents. The Utah Committee for a Glen Canyon National Park spent several years campaigning. William Halliday, who headed the group, did not oppose the Echo Park Dams. This stance may have been designed to curry favor from western politicians, but it likely alienated Brower and other conservation groups.

49Brower worried that Echo Park would be put up against Glen Canyon. He told Halliday and an ally, Malcolm B. Ellingson, in a letter on February 7, 1955, that although Glen Canyon sounded beautiful, he did not want to get trapped into comparing it with Echo Park. Conservationists were suspicious of the organizations supporting a national park at Glen Canyon. In December 1955, Congressman William Dawson of Utah mentioned the Glen Canyon national park campaign to Zahniser, who acknowledged that he had been getting letters about it for two years. Zahniser worried that it was part of a disinformation campaign against Dinosaur. “I at first wondered if it might be someone trying to mix me up,” Zahniser told Dawson. The Glen Canyon proponents were political neophytes. “We really did not know how to speak out,” said Ken Sleight, a river guide and member of one of the groups fighting the Glen Canyon Dam.

50Brower’s

support of a larger dam at Glen Canyon was not an aberration; he did at times support dam projects. Such support included campaigns to build bigger dams on the Snake River at Hells Canyon in Oregon and Idaho and on Flathead River in Montana. The alternative to the large dams at each of these sites would have been a string of smaller structures that Brower and the Sierra Club thought would create even more environmental damage. Brower’s willingness to compromise, to allow some dams rather than none, surprised some of his fiercest critics. Ottis Peterson, the public-information officer for the Bureau of Reclamation, was so pleased that he supplied some key details to Brower when he was developing his case for supporting the large Paradise Dam on the Flathead. None of the Flathead dams, including the Paradise, were built. The smaller Hells Canyon dams were constructed, and it appears in hindsight that neither Brower nor the environmental community clearly thought out the ramifications of their Hells Canyon stand. The massive dam they wanted would have presented a far more formidable concrete barrier for the fish that spawn in the Snake. It also might have encouraged federal dam builders to erect even more dams on the rich fishing grounds of the nearby Salmon River.

51Brower stressed to friends and colleagues that he wanted to be a pragmatist, not an extremist, and that small victories and compromises were worth the price. About the Paradise Dam, he wrote in October 1956, “Merely to say ‘we’re against all dams until . . .’ does nothing but lump us as aginners [

sic] with no specific alternative. It’s a sure formula for being ignored by all hands, including other conservationists.” McCloskey, whom Brower hired in 1961, said Brower taught him about compromise. “He emphasized when he first oriented me that the park system had been built incrementally, that it did not happen overnight with one big victory, but that it was systematic.” Brower told him he believed in incremental victories. That belief would later change.

52Brower finally got to the Colorado and into Glen Canyon, but not until after Congress had authorized the huge dam. It was an unforgettable trip, one he repeated for several years until the reservoir finally submerged most of the canyon’s beauty. “The river itself was a spectacular sight,” he said. “But the side canyons are beyond belief.”

53This was slick rock country, at times Navajo Sandstone, stained in vertical stripes. Elsewhere it was a vivid pink, the same rock, according to Stegner, as the intricate formations at nearby Zion and Capitol Reef. “It is surely the handsomest of all the rock strata in the country,” Stegner continued. “The pockets and alcoves and glens and caves which irregular erosion has worn in the walls are lined with incredible greenery, redbud and tamarisk and willow and the hanging delicacy of maidenhair around springs and seeps.”

54 Brower visited side canyons that carried names such as “Music Temple,” “Hidden Passage,” “Mystery Canyon,” “Twilight Canyon,” “Forbidden Canyon,” and “Labyrinth Canyon.” Water had undercut Twilight Canyon and created a cave so large, according to various reports, that it could accommodate either Madison Square Garden or the Hollywood Bowl. Mystery Canyon ended in another domed cavern, with a very large pool. The narrow walls of Labyrinth Canyon were so high that it was not possible to see the sky. Visitors seemed to favor Music Temple more than any other place. It was yet another domed chamber, 500 feet long and 200 feet high, of Navajo Sandstone. A break in the roof allowed a spool of creek water to pour down into a clear pool. The roof fissure served as a skylight. Stegner wrote, “The shadows in a chamber like this, the patterns of light and shadow, are miraculous and utterly unphotographable, and the walls re-echo with the slightest sound.” Alice Joy Keith, the San Diego woman who had visited Glen Canyon, said her party arrived “on a Sunday morning, as did John Wesley Powell, and like him, we held an impromptu service of song and praise to God.”

55Downstream there was one last spectacular rock formation seven miles east of the river, Rainbow Bridge. It was a sandstone arch 309 feet high with a span of 278 feet. The Navajos considered the natural rock bridge sacred, and a 160-acre parcel containing it had been declared a national monument in 1910. It was so isolated that only a few hundred visitors took the trouble each year to hike in to see it, but the reservoir meant that water would potentially be lapping at its footings.

56 Brower and his allies made sure that the legislation authorizing the entire Colorado River Storage Project, including Glen Canyon, would specifically indicate that no dam or reservoir could intrude into a national park or monument, including Rainbow Bridge. Perhaps, thought Brower, he could use Rainbow Bridge to stop the water from rising too high. Perhaps he could even use it to stop the Glen Canyon Dam altogether.

It has been more than half a century since Echo Park Dam was stopped and Glen Canyon Dam was authorized. Yet the victory at Dinosaur has been obscured by the loss of Glen Canyon, and Brower is more responsible for that loss than anyone else. Yet his martyrdom, his continued lament about his failure, obscures a central point; the clash over the Echo Park Dam was a historic milestone that could not have happened without his daring leadership. He succeeded where John Muir had failed. Never again would the federal government build a dam or other major invasive structure in a national park. Never again would the conservation community be as powerless as it had been in the past.

A major reason opponents of the Dinosaur dams organized was that many remembered how Muir had lost the fight at Hetch Hetchy. He had been unable to convince the federal government of the travesty of building a dam in such a beautiful sanctuary as Yosemite National Park. Dinosaur opponents began their campaign to protect the sanctity of national parks and to uphold the protections provided for in the National Park Service Act of 1916. Protecting those provisions became, in early 1956, more important than Glen Canyon, which did not have national park recognition. Historians have called this recognition that national parks can no longer be violated a watershed in both the history of the parks and the conservation movement. Bureau of Reclamation officials would attempt later to build more dams, including two at the Grand Canyon, but both of those projects as well as the others were outside of what was then the established park boundaries, so they required a different kind of fight. For environmentalists, the two proposed Dinosaur dams crossed a line, a national park and monument boundary line. The tragedy was that there was no such line around Glen Canyon, although there should have been.

Another difference from the Hetch Hetchy campaign was in the scale of the campaign mounted by conservationists. Muir had likewise run a nationwide campaign, but only a handful of conservation organizations joined him, and even the Sierra Club was divided. In contrast, historians have count at least seventy-eight organizations in the Dinosaur campaign. Most joined because they wanted to protect a national monument.

57 Would they have fought to stop the plan to enlarge and build Glen Canyon, the alternative that Brower himself had pushed to replace the Dinosaur projects? Brower maintained later that he did have the votes to end the entire Colorado River Storage Project. Yet the man who was developing a reputation for taking rash and reckless gambles fatally paused in the spring of 1956 when he had the opportunity to prevent Glen Canyon. We have only his regrets as an explanation of why he did not act.