I hope the American people remember well who the groups are who think so much of their present, and so little of everyone’s future, that they fight and stall this bill—the dammers, the sawlog foresters, the graziers, the miners, and strangely the oil men, who above all should know the importance of keeping America full to beautiful places to drive or to drive near.

DAVID BROWER, TESTIMONY IN U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION ACT

By the early 1960s, David Brower and his allies believed that they were close to getting Congress to pass a wilderness law. The new Kennedy administration strongly supported the bill; events were forcing the Forest Service and the Park Service to end their opposition; the Senate leadership was backing the bill; and even the Outdoor Recreation Resource Review Commission was no longer an impediment.

There was one problem: the congressman from the Western Slope of Colorado, Wayne Aspinall.

Interior Secretary Stewart Udall would call Aspinall “a very crotchety, difficult person to work with.”

1 Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, not only in the wilderness bill debate but also on a range of other issues, Brower and Aspinall would clash. After Aspinall lost the Dinosaur fight, he retaliated by refusing to release a bill making Dinosaur a national park. He was bitter about losing the Dinosaur dams and wary that the wilderness bill was another attempt to rob resources that he felt belonged to the West.

2 So for four years he blocked passage of the bill.

John Kennedy endorsed the legislation in 1960 while running for president; it was part of the conservation plank of the president’s New Frontier agenda; and the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress. Agriculture Secretary Orville Freeman and Interior Secretary Udall were in charge of getting the bill passed, and Udall emphasized the need for the law. “Wilderness preservation is the first element in a sound national conservation policy,” he said. Even after Kennedy’s death in November 1963, conservation and wilderness had a strong supporter in Lady Bird Johnson.

3That level of support made it difficult for the Forest Service and Park Service to oppose the law. But Brower’s increasing outspokenness and criticism of each agency did create some problems for a bill that was going to require compromises to get passed.

The Park Service’s position began to change as it moved away from its construction agenda and more toward the acquisition of new parks, thus earning greater support from most environmental advocates. Unlike the 1950s, the 1960s would be a time of major expansion of the national park system. Mission 66 had set the foundation for some of this change by surveying potential recreational land that might be threatened by development. That survey led to the creation by 1962 of three national lakeshores and three national seashores, including Point Reyes, California (

figure 9). Those parks contained more than 700,000 acres and 718 miles of shoreline.

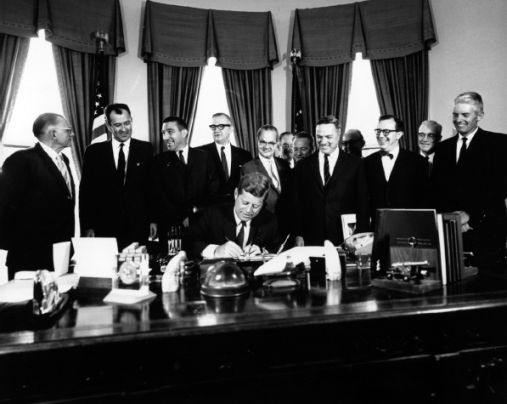

4President John F. Kennedy signs the bill creating the Point Reyes National Seashore on September 13, 1962. Those looking on include Congressman Wayne Aspinall (far left), Interior Secretary Stewart Udall (third from left), and Brower (far right). (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

With Point Reyes so close to Berkeley, Brower worked hard for the new shoreline preserve. He knew it well, having taken his family to the peninsula many times. Much of Point Reyes was cut off from the mainland by a rift in the San Andreas Fault, which ran undersea beneath the narrow Tomales Bay. The beach topography varied from sandy beaches and coastal bluffs to a three-mile long sand spit where herds of elk fed on the high grass that waved in the wind that swept across open meadows and knolls. Despite the Kennedy administration’s support, the campaign for the preserve was not easy; many of the landowners were opposed because property values were rising, and the patches of Douglas fir and pine had value on the timber market. Brower countered by commissioning a twenty-eight-minute film,

An Island in Time; sending out a flurry of press releases and brochures; and organizing a lobbying campaign in Washington, D.C.

5 It helped that the new president had a summer home on Cape Cod near the boundaries of one of the other protected seashores. Other park campaigns were less successful. Local opposition killed the Oregon Dunes and Oregon Cascades national park proposals. But more frequent success was obvious by 1972; by then the government had created eighty-seven parks and protected areas, including historical sites, which consisted of 3.7 million acres.

6Those efforts helped ease Conrad Wirth’s opposition to the wilderness bill. Yet Wirth remained angry at Brower and other conservationists, who he felt were too extreme, especially after Brower’s published critique of Mission 66 came out in 1958. In his autobiography, Wirth denied that the Park Service opposed the wilderness bill, but he also admitted that park support was withheld until Howard Zahniser redrafted some of the language to Wirth’s liking.

7The Forest Service reluctantly agreed to drop its opposition after most conservation organizations supported a separate bill sought by Director Richard McArdle. Brower was virtually the only environmentalist opposed to McArdle’s legislation, and his opposition nearly ended his friendship and alliance with Zahniser.

The legislation in question, the Multiple Use–Sustained Yield Act, had first been introduced in 1953, and it lingered for years until the Forest Service rewrote it in 1958. It was designed to ratify the type of planning that McArdle had already instituted. By 1960, the only foe to it besides Brower was the timber industry, which feared that the bill would dilute logging’s historic priority over other uses in the national forests.

8 Brower worried that this Forest Service legislation would kill the wilderness bill. On June 3, 1960, in a memo addressed to twenty-nine friends and colleagues, including Sierra Club leaders and representatives of other conservation groups, Brower spewed out his frustration with the Forest Service. He said efforts to work with the Forest Service and to protect wilderness were not working. The Forest Service wanted to cut trees; most of its revenue (95 percent) came from timber sales, and the multiple-use act was simply a guise that would allow logging everywhere, including the wilderness. Brower also believed that the bill locked the National Park Service out of acquiring forestland. The bill, he said, threatened the prospects for passing the wilderness bill and could spell further trouble for rounding out the wilderness system in parks and national forests.

9Although the memo was an excellent summary of Brower’s frustration, it came too late to stop the bill. McArdle had sent one of his assistant chiefs to the Sierra Club board meeting on May 7, and there was a long and cordial discussion about both bills. Two motions were officially approved, one urging that the multiple-use legislation allow some single uses in the forests and the other calling on the bill sponsors to ease the transfer of Forest Service land to the national parks. What came out of the meeting unofficially was an understanding that the Sierra Club would not oppose the multiple-use bill. In return, McArdle would soon drop his opposition to the wilderness bill.

10Even more striking than Brower’s refusal to make a deal with the Forest Service was that his position exposed a rift with Zahniser, who had supported the forestry bill. The same day Brower wrote the memo, June 3, he sent a separate note to Zahniser. After working with Zahniser for a decade, he said it was disappointing to see their routes diverging. Not only had Zahniser disagreed with Brower’s opposition, but he had also criticized it privately and publicly in at least two publications. There had been past disagreements, both with Brower’s backing of the North Cascades National Park and with the creation of the Scenic Resources Review. Zahniser had felt both efforts diluted the lobbying needed for the wilderness bill. He quickly responded to Brower’s letter. They had drifted apart, he acknowledged. For whatever reason, the phone calls and the meetings in Washington had virtually stopped, and Zahniser did not understand why. He said that he was no longer sure what Brower was doing, so he had felt it best to go ahead on his own in the public statements about the multiple-use bill. Zahniser added that he was pleased that Brower had sent both letters to him; at least they were talking again, and he hoped it would continue. Brower, who in future years would break so many ties with so many once close friends, did not part here with Zahniser, but the relationship had changed.

11Following Kennedy’s inauguration, the Senate convened, reorganized, and—in a key development for wilderness proponents—named Clinton Anderson of New Mexico the new chairman of the powerful Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. By September 1961, the Senate passed the wilderness bill overwhelmingly, seventy-eight to eight.

12Although support was strong for the bill throughout the nation, Aspinall knew that many in the West resented this intrusion into lands that they had always used. The House Interior Committee scheduled hearings in October and November in McCall, Idaho; Montrose, Colorado; and Sacramento, California. Turnouts were high; nearly five hundred people came to the Colorado hearing, forcing the committee to move into a larger movie theater. For every speaker who favored the legislation, more than two others opposed it. Brower spoke in Sacramento, joking that he had heard people ask what was going to end first, the hearings or the wilderness. The legislative process had already been exhausting, and by the time the bill was approved, it had gone through sixty-five versions and eighteen hearings.

13Brower was critical of those who had held up the bill for so long, declaring “it is high time for the public to blow the whistle on rapacity in its last vestige of the American wilderness.” He continued: “The important thing today is to stop the compromise, the shilly-shally, and hesitation that selfish interests press upon us and get on with the job. Every week of delay brings another short-term profit to a few and forecloses forever on something irreplaceable in the national estate.”

14In February 1962, the long awaited report was issued by the ORRRC, the outdoor commission that Brower had helped create. The ORRRC’s work had taken three and a half years, cost more than $2.5 million, and ultimately was a disappointment to Brower. The ORRRC supported establishing a wilderness bill, agreed that demands on parks and recreation would increase, and called for the creation of what would become the U.S. Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, which would supply federal funds for new parks. The bureau would go on to pave the way for park planning and unleash significant money for recreation in local, state, and national parks and recreation areas. But it also endorsed the multiple-use concept in many areas. “More than recreation is at stake,” Brower would complain later. “What is needed is a broad public understanding of the meaning of wilderness to civilization.” A friend in the Seattle chapter of the Sierra Club, John Warth, was so disappointed that he suggested the best tactic might be to call “the report a sham and use that to arouse public opinion.”

15However, Brower may have been too pessimistic because the report also strongly endorsed the need to establish wilderness areas in federal areas as well as the prohibition of mining, dams and water development, and other uses in these designated areas. To reinforce these endorsements, wilderness bill supporters took to the floor of Congress and read those portions of the report.

16Despite those pleas, the legislation remained locked in a House subcommittee, and by March 1962 many were very worried about its prospects of getting through the second chamber. “I have very grave doubts from the latest reports whether the wilderness bill will pass the House,” Supreme Court justice William Douglas, now a Sierra Club board member, wrote to Brower. “Every special interest seems to be against it. These are indeed very discouraging days.”

17The chief problem now was Aspinall. The Democratic congressman from Colorado had enormous power (

figure 10). Udall would call Aspinall “autocratic,” with the “good and bad traits of an industrious hedgehog.” Aspinall, Udall said, was “one of the last in this century’s chairmen to run his committee as though his vote was the only one that counted.” Aspinall did not like the bill, anymore than he liked the aims of most conservationists. If Brower and Wallace Stegner wanted to talk about spirituality, Aspinall would talk religion. God made the land to be used, Aspinall declared in one newspaper interview. The environmentalists, Aspinall said, were seeking a version of an earthly heaven, “and they expect everyone else to conform to their views.”

18

Wayne Aspinall served as a Democratic congressman from the western portion of Colorado from 1949 to 1973, and during much of that time he chaired the key House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, which oversaw dams, national parks, forests, and wilderness. He was often an irascible foe to Brower. (Courtesy of the Penrose Special Collection, University of Denver)

The western slope in Colorado never generated the political power, the money, and the prestige of Denver and the other big cities on the opposite side of the range. Aspinall would carry that chip on his shoulder, a belief that he was the underdog. He needed somehow to overcome the odds, to show “them”—be they front-range politicians, California environmentalists, or East Coast elitists. He grew up on a ten-acre peach orchard that was nourished by water irrigated from the Colorado. He understood the needs of the ranchers and farmers and how precious and necessary water was in the West. After law school, he ran for the state legislature and won in 1930, rose through the ranks, and wanted to run for governor. In 1948, he had to settle for the Fourth Congressional District. With the aid of Harry Truman’s coattails, he made it. His district covered all of western Colorado, a rugged, high-mountain land good for grazing and mining, with valuable lead, zinc, and silver deposits. He sought out the committee assignments that would protect his district’s water and mineral interests. Then Dinosaur made him a player on the national scene, the go-to authority in the House when it came to dams and water in the West. As he became increasingly powerful, he also grew more conservative. In the late 1960s, Brower and his new employee, Jeff Ingram, encountered Aspinall in a Washington restaurant. After introductions, Aspinall exclaimed to Ingram, “You have more hair on your face than I have on the top of my head.” Ingram knew it was not a compliment. He soon shaved the beard. In the 1960s, after race riots broke out in major cities, Aspinall declared it was time for the white majority to stand up for its rights. “Those who dissent, must dissent within well-defined limits,” he said, “and must not be led by shysters.”

19From 1961 to 1964, Aspinall controlled the fate of the wilderness bill and came under heavy attack from environmentalists and the press.

20 In

Harper’s, Paul Brooks accused Aspinall of singlehandedly thwarting the overwhelming popularity of protecting the wilderness in Congress and the nation. “Aspinall’s chief ally is not so much public apathy as it is the apparent complexity of the problem,” wrote Brooks. “His master plan for 1963 is beautifully designed to confuse the issue to the point where clear judgment becomes impossible.”

21The lead role in lobbying for the bill remained with the gentlemanly but persistent Zahniser. Brower was just too caustic at times to work the deals that needed to happen to get the bill through Congress. Yet Brower could be surprisingly cooperative at times. In a House Subcommittee on Public Lands hearing in May 1962, Brower toned down his criticism of his opponents while urging passage. The wilderness, he warned, was in danger. “It is not reassuring enough to know that excessive damage has not yet been done,” he said. “You can’t claim a dropping egg is safe merely because it hasn’t broken yet. We can measure the need for the wilderness bill by the very intensity of the effort to defeat it.” He was even more conciliatory under questioning from Congresswoman Grace Pfost from Idaho. Roads into wilderness areas should be closed, and new transmission lines rerouted, he said. But livestock ranchers could still graze in the designated wilderness areas, and even dams and reservoirs might be permitted under some circumstances. “We might wish to argue a bit about that,” he said, “but we want to be reasonable.”

22In the spring of 1963, the Senate passed yet another version of the bill and sent it to the House. Aspinall remained maddeningly difficult to pin down on his intentions. One day he was conciliatory, the next he was defiant. A writer for the

Washington Post, Julius Duscha, met Aspinall off the House floor in April 1963 and asked when hearings would occur on the bill. “I don’t plan to hold a thing at the present time,” Aspinall replied. “If by calling names and putting pressures, they think they can move me any faster than I intend to move, they’re mistaken.” The interview ended, and Duscha noticed that Aspinall was hurrying back to the floor. A bill affecting silver mines in Aspinall’s district was under consideration.

23Yet Brower remained committed to the battle. In a letter to an old friend, Ike Livermore, about the need for the bill, he recounted a story. Two weeks earlier, he had been coming back from a ski trip at Squaw Valley with his sons Ken and Bob. They had to slow to pass some road construction. The highway was being widened to four lanes. A moment later, Bob told his father how much better off the older generation had been.

Brower asked his son what he meant.

Bob said his younger generation faced the potential for nuclear war, and now the mountains were going, going, going.

24In the fall of 1963, Brower sent staffer Mike McCloskey to fight Aspinall within his own district. When McCloskey arrived in Grand Junction, Colorado, he literally had no plan and no allies to help him. He walked into a sporting goods store and asked a clerk who in the area might care about wilderness. He was told packers and guides cared, and there was a list, produced by the state Game Department, with names, addresses, and phone numbers. For several weeks, McCloskey tracked down each guide, discussed the need for the wilderness bill, and in most cases got the guide to agree to send a telegram to Aspinall. McCloskey would write down what they wanted to tell Aspinall and then find a telegraph office and wire the message. Aspinall could literally track McCloskey’s work as the telegrams came in, and he complained about how Brower had sent outside agitators into his district. But McCloskey always felt this telegram campaign was a very effective tool in nudging Aspinall toward passing the bill.

25Finally, House hearings were set for December 1963 at the Capitol and in Denver. Brower testified in Washington; he sent McCloskey to Colorado. In the most recent hearings, the number of speakers on each side had come close to splitting even, with opinion clearly tilting toward the wilderness side.

26 It was not yet well known, but Aspinall had had two key meetings and was prepared to stop blocking the bill. One was with Senator Clinton Anderson, the second was with Kennedy, just two days before the president went to Dallas, Texas, and was assassinated. A series of deals were cut; the most important was that Aspinall was able to add a provision allowing mining to continue in the designated wilderness areas for another twenty years.

27A final vote was scheduled for the summer of 1964 when Brower received a telegram the morning of May 5. It said that after a normal day at the office, Zahnie had died in his sleep early the following morning.

28 He had a heart condition, it was well known, and yet his death from a massive heart attack at the age of fifty-eight was still shocking. Brower remembered Zahniser and his family meeting up with the Brower family above Stehekin the summer he did the film on the North Cascades. The film shows Zahnie, who by then knew he had a weak heart, plodding at a slow but measured pace up the trail from White Pass toward Glacier Peak. He may have tired on such trails, but it was where he wanted to be, in the wilderness. In some respects, Brower said in his eulogy of Zahniser, it had been political madness to take on so many opponents in the fight for the wilderness bill, but Zahniser had the political fortitude to preserve. “The hardest times were those when good friends tired because the battle was so long,” said Brower. “Urging those friends back into action was the most anxious part of Howard Zahniser’s work. It succeeded, but it took his last energy.”

29The bill passed in August, and President Lyndon Johnson signed it into law as the Wilderness Act in September in a ceremony attended by Howard Zahniser’s widow, Alice. Days before the bill’s passage, Wirth asked Aspinall if there were any way it could be named after Zahniser. Aspinall said he only knew of bills that could carry the names of legislators, and sometimes they should not have gotten credit. Zahniser was deserving, but nothing could be done.

30Brower and other conservationist were upset with two major amendments to the new law. One, noted earlier, gave miners another twenty years to operate in the designated wilderness areas. A second amendment removed the administration’s authority to create new wilderness areas, leaving it to Congress. “The result was, hardly a compromise—it was, rather, an acceptance of Aspinall’s terms,” wrote James L. Sundquist, a scholar at the Brookings Institution. Despite the flaws and changes, the structure of the bill still incorporated conservationists’ early aim—to protect lands that had been untrammeled. Brower declared that the bill’s “passage was the most significant conservation development in this decade and perhaps the most significant since the National Park Act of 1916.”

31The law designated fifty-four areas in thirteen states as wilderness. They totaled only slightly more than 9 million acres, but the law allowed for other lands to be considered, a provision that resulted in lengthy hearings that went on for years. Ultimately, the provision was a blessing. In the fifty years after the act was adopted, the nation set aside 757 areas in forty-four states, comprising 109,511,966 acres, about 5 percent of the entire United States or an area slightly larger than California. In some respects, the growth in the number of areas set aside reaffirmed the popular support for wilderness preservation in the United States. Fifty years after its passage, the law remains a landmark in conservation and environmental history, establishing statutory protection to wilderness for the first time. It inspired the existing generation of conservationists and launched a new breed who would continue to work for more protection. However, environmentalists and scholars have also criticized it, contending that land undeveloped by roads or other intrusions was far less important than poverty, pollution, and other problems in both rural and urban communities. Others criticized early efforts to remove native peoples from some national parks and wilderness areas and suggested the concept of wilderness preservation was ethnocentric, if not racist, because it benefitted privileged whites primarily. Finally, some ecologists have remarked that land, even when left alone by humans, still undergoes changes over time, which raises the question of what is truly being preserved.

32The bill was designed to protect wilderness in the United States permanently. But one of Aspinall’s amendments that did not survive when the bill was passed demonstrated how protection is never entirely guaranteed. The amendment called for a ski resort to be built in the middle of what would be the San Gorgonio Wilderness in southern California. Developers had not given up. In 1961, a proposal surfaced for a resort with parking for five thousand cars and fifteen ski lifts. The Forest Service rejected the proposal, relying on the decision it made in 1947 when it listened to Brower and the Sierra Club in rejecting a similar plan.

33 The amendment popped up again in a House version of the wilderness bill in 1962. After the Sierra Club and others objected, the amendment was dropped. New special legislation on San Gorgonio was introduced once more in 1965. Congress held new hearings, opposition remained high, and the ski resort was rejected yet again.

Today, many U.S. wilderness areas have geographic names, such as San Gorgonio, which draws a heavy stream of backpackers and day hikers on foot.

34 Other areas have names that are either more or less descriptive, such as the Three Sisters Wilderness in Oregon, the Glacier Peak Wilderness in Washington, and the Inyo Mountains Wilderness in California. A few are named after individuals, and, as Aspinall told Brower, some individuals are less deserving than others in having a landmark named after them. Areas named after dedicated conservationists include the Ansel Adams, Bob Marshall, John Muir, Theodore Roosevelt, and William O. Douglas Wildernesses.

There is no David Brower Wilderness or Howard Zahniser Wilderness, and certainly none was named in honor of Wayne Aspinall.

35