You are villains not to share your apples with the worms. Bite the worms. They won’t hurt nearly as much as the insecticide does.

DAVID BROWER, IN RICHARD SEVERO, “DAVID BROWER, AN AGGRESSIVE CHAMPION OF U.S. ENVIRONMENTALISM, IS DEAD AT 88”

In 1959, the Sierra Club board ordered David Brower to be polite to public officials. Richard Leonard and Ansel Adams had consistently defended Brower’s increasingly sharp language, but others on the board were uncomfortable with his tactics. They worried that he was causing more harm than good. The board adopted a resolution that said that employees needed to be cordial in dealing with or discussing public officials and issues.

1 Brower called the resolution a gag rule. To him, he was being told that he could no longer criticize any government official or agency. His supporters questioned how an environmental activist could be tactful in defending the environment. One could not be both polite and aggressive in making a point, said Hugh Nash, a Brower staffer and editor of the

Sierra Club Bulletin. There was no way anyone should delude themselves in thinking Brower could do both, he said. If an individual rarely offended anyone, Nash felt that individual should be fired.

2For those with a cause, this debate is endless—violence versus pacifism, ultimatums or compromise, hostility as opposed to conciliation. For years, the Sierra Club debated what tactic is best. At one board meeting, Brower argued that open hostility with government officials worked, and being polite did not. Some of this debate was with the old guard, the conservatives of the past, but some was also with the new generation that took over in the 1950s, some of whom did not want to go as far as Brower. Edgar Wayburn responded at that same meeting that scathing criticism was warranted only when “we have reason to be scathing.”

3It was not just tactics, however, that concerned many of these board members. They worried that Brower plunged into controversy less for the cause and more for personal attention. “He coined the phrase ‘No blind opposition to progress but opposition to blind progress,’ ” said Wayburn. “He was impatient: the earth was in a state of crisis; the time for action was always now. Nor was he above using guilt as a primary motivator for preservation. ‘If enough people care’ was one of his pet phrases in ads and books. Brower displayed no reservations about saying he was against anything or anyone.”

4Such resolutions precipitated the beginning of a rift between Brower and the Sierra Club board. He felt that he was always several steps in front of them. “It was such a severe restriction that that was the main thing that drove me to the publications program,” he said later. “I couldn’t do what I was doing in speeches and articles, and I tried to get this general attitude out in books.”

5Was Brower tiring of the job and the organization that he loved so much? In January 1961, he responded to a request by the newly appointed secretary of the interior, Stewart Udall, to name potential candidates to become Udall’s director of information and associate director of the National Park Service. In an eleven-page letter, he offered a number of names, and the last one for each post was named Brower. Brower said that he was not looking for a new job; he already had one that was increasingly challenging. But the opportunity to work with Udall inside government, instead of outside, was irresistible.

6A month earlier, Ansel Adams had also written to Udall urging that he hire Brower. He said Brower was not aware of his proposal, and he praised Brower’s “amazing courage and tenacity” in protecting natural resources and his knowledge and experience in dealing with conservation issues. Surely, said Adams, there was a place for Brower, with his extraordinary talents, in the Kennedy administration.

7When Udall demurred, Brower went to Europe. In the summer of 1961, the Brower family spent three months touring the continent. “My mother had always wanted to go,” recalled Barbara Brower, who was eleven at the time (brother Ken was seventeen; Bob, fifteen; and John, nine). “She did all of the reservations; she planned out every aspect of the trip,” said Barbara. “She figured out where we would stay and how we would acquire a car in Germany and renting out our place here.” They met David’s brother Joe and Joe’s wife, Gayle, in Zurich, where Joe was stationed as a commercial airline pilot. Brower and his brother hiked in the Italian Alps, rediscovering some of the places he had been during the war, while Anne and Gayle Brower stayed more in town, including making visits to pastry shops.

8 It was Brower’s first real vacation from the Sierra Club in nine years.

When Brower returned to work, he would devote most of his time to the publication program while staying at the Biltmore Hotel in New York. It would become a second home, and when he was not at Barnes Press, he would haunt the jazz clubs. On rare occasions, Anne or one or more of his children would come with him to New York, but he mostly traveled alone. That made liaisons easier, and in New York Brower’s sexual choices were “an open secret,” according to Gary Soucie, a field representative for the Sierra Club based in New York.

9The long absences meant that the four children were growing up without their father. “I have a collection of birthday cards,” said Barbara Brower. “He was often not home for my birthday, but he always called. While he was absent a lot, he was a very loving dad.” The eldest, Ken, described how other children would be confused when he would tell them that his father worked as a conservationist. No one knew what it meant. “It was embarrassing,” said Barbara Brower. “It was hard to explain what he did.”

10Brower was rarely home for dinner, but when he was, Ken recalled, his father often dominated the conversation, turning it into “a discussion of the beauty of the natural world, or the cleverness of evolution, or the obtuseness of humanity, or the task ahead in salvation of the planet.” These intense bursts of energy and domination could be both annoying and exciting. As a teenager, Ken would sometime call his father “the Gee Whiz kid B.”

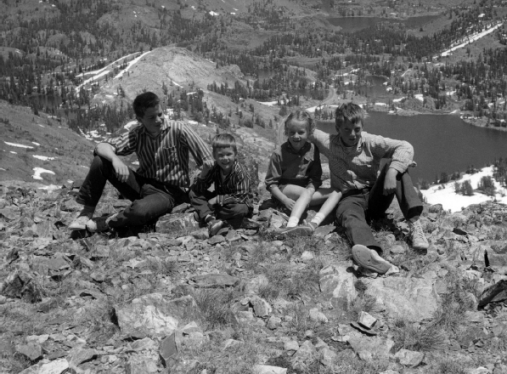

11 Their father was not saddled with the conventional thinking of his generation, and the children found that disconcerting (

figure 12). “As a father, he spoiled the ’60s and the counter-culture for me,” said Barbara. “We were already there, and there wasn’t any place to go.”

12

David and Anne Brower’s four children take a rest (left to right): Kenneth, John, Barbara, and Robert. The two oldest, Ken and Bob, often accompanied Brower on hiking trips in the 1950s. Barbara and John would join their father on a hiking trip on Nepal’s Himalayas many years later, when Brower was sixty-four years old. (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, and the Brower family)

On Sunday mornings when Brower was home, he would host strawberry waffle breakfasts for anywhere from fifteen to forty guests. The crowd would fill the main rooms of the house and spill out into the patio, with Brower in the kitchen, several sets of waffle irons going at once. It was a recipe he perfected, calling for Bisquick, oat bran, milk, eggs, grated zucchini, apple, carrots, and a shot of Worcester sauce. Brower was sometimes asked to write down the recipe. One inquiry came from a book publisher who pointed out that Brower’s recipe did not include strawberries even though he called the dish strawberry waffles.

13If there were rifts in the relationship between Brower and his wife, they kept them to themselves. With four growing children and a monkey for a pet, the house was often less than spotless. Anne Brower had very little use for housecleaning, and Brower was a pack rat, but she was the glue that bound the family.

14 Brower could be trying, such as when he delayed their departure for an engagement by playing the piano. Yet the couple’s intellectual bond remained strong. Barbara Brower remembered her parents reading the

New Yorker series written by Rachel Carson about pesticides to each other in the car in 1962 and talking about it. “They were deeply impressed,” she said.

15The 1960s introduced new ideas about race, sex, music, lifestyles, and even science. Brower mingled with some of the nation’s best and brightest thinkers, who were considering such fundamental issues as how to best protect the earth. Michael McCloskey, who would work closely with Brower and eventually succeed him, could see how this contact was affecting Brower. “It was very clear to me in the ’60s that he was spending more and more of his time in the East and around the world and that he was around great thinkers of the environment that did influence him. They kept broadening his horizon and giving him ideas on how to save the environment. When I would meet with him over lunch he would talk for quite awhile about how he spoke to whomever and got a better idea of this.”

16There was Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas,

New York Times writer John Oakes, editor and author Paul Brooks, and noted University of Pennsylvania anthropologist Loren Eiseley. Brower was on college campuses for speeches, and he enjoyed mingling with students. But he often drew greater satisfaction and intellectual stimulation from the faculty. Barbara Brower said her father was very good at listening. “He was also a very curious person,” she said.

17 In 1962, Douglas forwarded to Brower an inquiry he had received from the Ford Foundation, which was interested in funding work in environmental activism and education. Brower responded by writing a detailed fifteen-page proposal. Although the proposal was never funded, it offered a fascinating blueprint of what was ahead for the American environmental movement. He told the Ford Foundation that two major priorities should be considered: improved environmental education and preserving land of “irreplaceable value.” Government and environmental organizations would eventually embrace the latter concept. Examples range from local land trusts and conservation easements to government and nonprofit organizations such as The Nature Conservancy that have preserved literally hundreds of millions of acres both in the United States and around the globe. His environmental educational ideas ranged from producing more television programming to new curricula in higher education. Television was only beginning to discover wildlife shows, and colleges were still years away from developing environmental studies and conservation biology programs.

18 These ideas are characteristic of Brower, who was a visionary. He was sometimes so far ahead of others that he would grow impatient when they could not keep pace with him.

Brower met Rachel Carson at a banquet in New York. Their friendship would be short, Carson died of cancer only two years after her polemic on pesticides was published. In October 1963, when she took a trip to San Francisco, Brower, Anne, and Barbara accompanied her to nearby Muir Woods National Monument to see the redwoods. Barbara recalled that Carson was somber but very impressed by the behemoth redwoods. She was frail and needed a wheelchair, which they pushed along the park’s paved paths. After Carson’s death, her will provided for a significant financial gift to the Sierra Club.

19Brower had voiced concern about pesticides, especially aerial spraying to control lodge pole beetles in Yosemite, since he had become the club’s executive director. The club struggled with the issue because many members were upset by how an insect infestation could turn green healthy trees into a forest of brown, dead sticks across thousands of acres. Others worried more about the health and safety risks from poisons sprayed in the air. The club’s policy would evolve from conceding to limited spraying in national parks in the 1950s to opposing all pesticide use in 1964.

20The Sierra Club was evolving and expanding. New Sierra Club chapters were at work with new local conservation efforts: Great Lakes, Rocky Mountains, Rio Grande (New Mexico and western Texas), the Lone Star, Grand Canyon, and Mackinac (Michigan). Brower could show up anywhere in the nation to express concerns about an environmental issue. It might be a hearing in New York opposing a hydroelectric plant at Storm King Mountain in the Hudson Highlands, in Hawaii to support the creation of Kauai National Park, or in Missoula, Montana, to explain his developing conservation creed.

21By now he was a polished speaker who was quite skilled in winning over an audience. Part of the attraction came from his tall stature, his broad shoulders, his melodious alto voice. Part came from the eloquence of his encyclopedic recanting of facts and stories—some of which were embellished or not factual. And part was just an intangible, magical trait. Years later, when Barbara Brower was teaching at the University of Texas, she invited her elderly father to talk to a class. Many of the students were not that interested in the environment, and Brower was ill—he looked gray. The talk began poorly, but the more Brower spoke, the more alive he became, the more his color improved, the greater his pace. The reaction from the students was even more intense as he caught their attention and captivated them. “By the end of the talk, they were on the edge of their seats,” Barbara Brower recalled. “That was the night we went out and closed out the bars.”

22Brower was so busy that he often had to delegate important campaigns, even when they were in the Sierra Club’s own backyard. In the 1950s, he had testified against a proposed Trans-Sierra Highway that would have slashed across some of the mountain range’s most isolated and scenic wilderness. But by 1964, he was telling Eunice Elton of San Francisco that local people needed to pick up the fight. Good campaigns win because of individual effort, not because of what the staff at headquarters could do, he said. Ultimately, it was a local coalition that successfully blocked the highway.

23After passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, the club established two top goals: establishing national parks in the North Cascades and the redwoods and blocking dams in the Grand Canyon. Brower assigned McCloskey to head up the North Cascades and redwoods campaigns, although Wayburn eventually took over much of the redwoods project. Brower, even though he was heavily committed to producing more books, assigned himself to lead the Grand Canyon fight.

24 Although those goals were the priorities, other issues were unavoidable, such as the proposed nuclear power plant near San Luis Obispo, California, and a ski resort planned in Mineral King, south of Sequoia National Park.

25By now, Brower had far more resources to call on when an unexpected campaign developed. The staff was growing rapidly. In 1959, the club had twelve employees; by 1963, it had thirty-three.

26 Separate departments were responsible for outings, publications, conservation, membership, and finances. Brower was fully involved in hiring employees in the areas he cared the most about, so loyalty to him was especially high in the publications and conservation departments.

27Yet administration was never one of Brower’s strengths, and the hiring process was confusing. Brower sometimes followed the rules and brought on new employees only with the board’s authorization. Other times he hired employees without consulting his bosses. Sometimes the board told him not to fill a position, but he did it anyway.

Brower was especially interested in adding regional representatives in the Pacific Northwest, the Southwest, the East Coast, and Washington, D.C. There was a clash about whether to have a Washington office, with Brower arguing he could no longer do all the lobbying.

28 The costs of some of these positions were shared with other local environmental organizations. But when Brower wanted to hire an East Coast field representative, the board turned him down.

Brower ignored the order and hired Gary Soucie, although he called him “assistant to the executive director” instead of “East Coast representative.” It would be weeks before Soucie discovered the ruse. “If I had known it, I would have said absolutely no, absolutely no way,” he recalled. But Soucie was talented, especially in dealing with the New York press, so the board eventually relented, and he eventually took the title Brower originally meant him to have.

29Brower often undercut the board’s orders by using his expense account, which would rise to $30,000 a year, 50 percent higher than his annual salary. Brower called the account his mad money, and he would use it for whatever purpose he wanted, an arrangement the board agreed to for years.

30According to Stephanie Mills, his management style was loose, chaotic, and erratic. A former worker at the Sierra Club, she described it as “maddeningly unbureaucratic and refreshingly nonprofessional.”

31Brock Evans was hired as the new Northwest field representative after McCloskey moved to the San Francisco headquarters. Evans described his first trip to San Francisco and going into Brower’s office as if he were a marine private, “reporting for duty as ordered, sir.” It was a joke, but Brower did not laugh. Evans, who was eager to work on the North Cascades campaign, asked about a plan. He wanted to know the priorities, the battle map, the design of the attack. “I’m your chosen instrument,” said Evans. “I’m your spear point. Tell me what to do, and I will do it, sir.”

“What the hell are you talking about Evans?” Brower replied.

Evans persisted, asking about a plan. Finally, Brower told him there was no plan.

“Well, what should I do?”

“I don’t know, Evans. What would you like to do?”

Evans described options for the North Cascades. When he concluded, Brower said, “That sounds great; go ahead and do it.”

32Both Soucie and Evans said they were never quite sure what specific areas their territories entailed. Evans elected to take everything north to the Arctic Circle. Soucie had the entire East Coast, but he was not sure about who was representing places such as Michigan and Kentucky.

Evans remembered that on his first trip to Washington, D.C., Brower told him to do some lobbying. Evans asked how he was supposed to do that. “I don’t know,” replied Brower, “just do it.”

33Soucie said he also never quite knew what to expect from Brower. One day he got a call from Brower cryptically asking that he meet him the next day in Washington, D.C., for breakfast.

“Should I bring a toothbrush?” Soucie asked.

“Probably a good idea,” Brower responded.

The next morning, Brower told Soucie that the Sierra Club was running a newspaper advertisement in the

New York Times and the

San Francisco Chronicle opposing a dam project. Brower wanted a press conference in Washington.

Soucie asked, “We’re not running it in the Washington Post?”

“No, we don’t have the budget for it,” replied Brower.

“How is this newsworthy in Washington?”

“You’ll figure it out.”

Soucie also did not know anyone in the Washington press corps. Brower gave him a name to get started, and Brower was pleased with the resulting press conference.

“He gave subordinates a lot of freedom,” added Soucie. “He would let us have full rein, and I don’t think any of us took advantage of it. We worked very hard.”

34Brower’s most complicated relationship on the staff was with McCloskey. After McCloskey had worked for three a half years as the Northwest field representative, Sierra Club board president William Siri asked him to come to San Francisco as assistant to the president. Brower had repeatedly praised McCloskey, but he opposed this plan. Siri rejected Brower’s objections but wondered why Brower was so opposed. He said that Brower’s arguments disturbed him; if McCloskey was not qualified to come to San Francisco, by extension one could argue that McCloskey also was not fit for what he was currently doing in the Northwest.

35McCloskey was unaware of Brower’s opposition, but when told about it years later, he was not surprised. The board had created the position as an attempt to control Brower. It wanted a full-time employee in the office to gather information and pass it on to the board. From Brower’s standpoint, McCloskey had been brought in as a spy. McCloskey attempted to defuse an uncomfortable situation by consulting with Brower. Brower responded well, and the two got along. But McCloskey never liked the situation, and after a year he proposed a new post for himself as conservation director. With Brower spending so much time in New York, McCloskey coordinated all conservation efforts for the club. Both the board and Brower liked the arrangement.

36The new position gave McCloskey greater freedom, especially in the North Cascades and redwoods campaigns. Although on paper the field and Washington representatives answered to McCloskey, he often felt that Jeffrey Ingram in the Southwest and Soucie in the East ignored him and talked only to Brower.

37 Both Ingram and Soucie deny this claim, and the Sierra Club records do show a trail of correspondence from Soucie to McCloskey.

38McCloskey and Brower worked reasonably well together, considering that McCloskey was the mild-mannered lawyer and Brower the verbal-bomb thrower. “Mike McCloskey and Dave had an odd relationship because their approaches were so different, although they did get along well,” said Soucie.

39 Brower would confide potentially damning information to McCloskey, who never passed it on to board members, even when asked. McCloskey was alarmed by how much Brower drank during the day and turned down Brower’s martini luncheon offers. “I was very abstemious,” McCloskey said. “I did not want to buzz my brain for work.”

40Brower’s sexual relations with men apparently were never raised as a problem in the workplace, but at times it was an issue. Both McCloskey and Ingram said that Brower sexually propositioned them at hotels or resorts where they were attending conferences or other meetings. And McCloskey sometimes worried that Brower was hiring a great number of young men more for their perceived sexual orientation than for their commitment to the environment and that, as a result, their work was not of the highest caliber.

41Brower also struggled with the bookkeepers and accountants, who often produced financial reports bewilderingly different from Brower’s. In 1963, the board reorganized the club’s finances and hired a new financial manager, Clifford Rudden. Brower liked Rudden, and when he was in San Francisco, they would sometimes go out for one of Brower’s long and sometimes tipsy lunches. But Rudden also sized up Brower and decided that to protect his own reputation, he would answer to the board as much as he answered to Brower. The situation was combustible.

42Sierra Club finances rode a roller coaster that was becoming increasingly difficult to control. It was not just that the club teetered between budget deficits and surpluses, but bank loans and book inventories kept growing. Total revenues would increase from $208,000 in 1960 to more than $3 million a decade later, and when the club missed finishing a year in the black, it sometimes missed badly. The good news was that money coming in from new memberships and from the wilderness outings kept growing. The bad news was that the cost of book publications also kept increasing, and between 1963 and 1969 the publications budget always finished in a deficit.

43In budget discussions in the mid-1960s, Brower assured the board that he was deeply concerned. Sometimes he would devote days and weekends struggling through all the numbers. But he rarely wanted to make cuts, no matter how dire the situation. Rampant pessimism, he said, was not wise when the Sierra Club seemed to be achieving so much in the field of conservation.

44Longtime board member Lewis Clark said club leaders knew for years that Brower was financially reckless. “We should have blown the whistle earlier,” he said. “We kept feeling, ‘He is a very valuable person to the club. He’s a good spokesman.’ We didn’t want to stop his good work. So we thought, ‘Perhaps we can reform him.’ ”

45Brower’s generous spending from his expense account did not reassure his bosses. His salary remained comparatively modest for a national leader of his stature, but his lifestyle and his expense account were far richer. Evans remembered staff meetings in San Francisco. “David liked to do things first class,” he said. “Often at the Francis Drake Hotel there were martinis served. He liked good things; that was David’s style.”

46 It was not the smartest message to send, however, when the board worried about budget deficits. “He was running up a $700-a-month bill at the Alley, the little local restaurant,” remembered Adams. “Anybody comes to town, he’d take the whole staff out to lunch, put it on the chit. Dick Leonard was acting treasurer and began to see these things come in.”

47Virtually every club president struggled working with Brower and his difficult personality. The burden may have been the greatest on Wayburn, a physician who led the club twice, from 1961 to 1964 and again in the tumultuous years from 1967 to 1969. Wayburn was often caught in the middle between appeasing a board that wanted to crack down on Brower and his own concern that such discipline would smother Brower’s brilliance. “I would have conflicts with myself as to how this should be handled. In large part, I believed in giving Dave his head and did,” he said. “I had to compromise a number of occasions in trying to bring together the wishes of the directors and the actions of the executive director.”

48Brower first worked with Wayburn when the physician joined the club’s Conservation Committee in the early 1950s. Brower shared many of the same values as Wayburn—their love for the outdoors, their prodigious work habits, and their desire for power. And yet Wayburn was also different, with his Deep South Georgia roots and Harvard medical degree. He had stumbled into the Sierra Club when he was recruited to join the high trips because organizers needed a physician. He stayed with the club until his death at the age of 103. Wayburn claimed that he sometimes worked ninety hours a week between his physician calls and the administrative work he did for a medical society and the Sierra Club. His greatest accomplishments were protecting the redwoods and later protecting the Alaska wilderness, campaigns that his wife, Peggy, joined in an equal partnership.

49Wayburn liked being in power in the club, and he held that power as long as he could. He was elected to the board in 1957, and after he became president four years later, he would often have lunch with Brower, when Brower would complain about how his enemies in government, industry, and even on the Sierra Club board were attacking him. “Dave was always of the opinion that someone was out to get him,” said Wayburn. “Dave had a strong paranoid streak in him, a strong paranoid streak.” For years, Brower threatened to resign each time he hit a new obstacle. The threat would dissipate after he calmed down. But in the mid-1960s, Wayburn warned him that board opposition to his tenure was growing. “Dave, if you resign this time, I think your resignation might be accepted by a majority of the board,” Wayburn told him. Brower wanted a board that advised only, not one that actually set policy, especially if that policy opposed what he wanted to do.

50In the early years of his tenure, Brower had reported on a regular basis to the board and its president. Even then, though, there were lapses, and by the 1960s Brower was seeing very little reason to communicate except when it was in his best interest. “Dave was brilliant but demanded absolute self-rule,” Wayburn commented. “One of his most used expressions was ‘follow me.’ ”

51Theories varied on why Brower was given so much freedom. Glen Dawson, a longtime Sierra Club member, said Brower had too many friends on the board. “I think they gave him too much leeway,” he said. “They had grown up together, known each other, climbed together, and skied together, the whole bunch of them.”

52That was only part of the problem, said Phillip Berry, who was thirteen when he first met Brower and who would eventually serve on the Sierra Club board. “From Dave’s perspective, the expectation was that if you climbed rocks, you loved the mountains, and therefore to save them was good,” he said. The board “had expectations too. They knew more about finance and knew how to deal politely with these outside influences, the Forest Service, the corporations, what have you. As board members they thought he at least ought to listen in the selection of methods. There developed out of all that a kind of a mutual disrespect.”

53To a certain extent, the friction between Brower and his board was mirrored at some other conservation organizations. Historians have pointed out that many conservation organizations, including the Sierra Club, had amateur, volunteer leadership for their first fifty years. By the 1960s, professional staffs were growing not just at the Sierra Club but at other organizations such as the Wilderness Society and the National Parks Association.

54One reason why the situation may have been more corrosive at the Sierra Club was that Brower and many of the allies he recruited to the board had a poor opinion of many of the Californians on the board who had been serving for years. Brower said that Justice Douglas called the Sierra Club board “a combination of a mourner’s bench and ladies’ sewing circle.”

55 Brower once provided a remarkably candid assessment of the board to Paul Brooks. In a letter written in February 1965, he urged Brooks to read it and then burn it. He stated that the current board had six leaders and nine followers. On too many issues, the board was parochial, with all but one representative from California. It was also stagnating because four had been on the board for twenty-four to thirty-nine years. He said that only a handful of board members had a sense of the club’s national role or were on the correct side on issues such as the dangers of pesticides.

56Brower remained protected by many loyal followers on the board, including Martin Litton, Patrick Goldsworthy, Eliot Porter, Ansel Adams, Richard Leonard, Wallace Stegner, and William Douglas.

57 Some would never drop their allegiance. “Brower has great charisma, and he has an army of devotees who think he’s just the second coming,” said Adams.

58 As late as 1965, the majority of board members continued to rally around Brower when he was attacked by former Sierra Club president Joel Hildebrand. A chemist with a national reputation at the University of California, Hildebrand dramatically resigned in May 1965 from the club he had once led because, he said, Brower had made “ridiculous statements” about the dangers of chemical fertilizers in the December 1964 issue of the

Sierra Club Bulletin. Further, Brower and his staff refused to publish Hildebrand’s rebuttal. “The curious result is that the Sierra Club does not permit a member to criticize the published utterances of an officer, utterances that abound in criticisms,” said Hildebrand. Hildebrand said that no one could control Brower and that “the organization that I have served with faith and enthusiasm is operating in ways that I regard as undignified, ignorant, futile, and offensive, ways that may even prove dangerous.” Hildebrand’s resignation surprised Stegner, who wrote a letter of support to Brower. Adams, who by now had begun to harbor increased doubts about the executive director, also defended Brower, but he also worried that such internal clashes “weakened the public image of the club.”

59Soon after the Hildebrand episode, Brower began to lose support from two board members who had long meant the most to him: Adams and Leonard. Brower had hiked, skied, and climbed mountains with Leonard; he had often been in Leonard’s home; and Leonard’s wife, Doris, had been nearly as close to him. The break was not easy.

“We were very close,” recalled Leonard. “Dave was extremely generous with praise. He used to tell the board of directors with great praise how much money Dick Leonard had given to the Sierra Club by his free legal work. Dave was very proud of what I was doing and was very generous with his statements, and I was very proud of Dave. We worked together magnificently all the way through the Dinosaur campaign.”

60But they both slowly changed. The personal friendship drifted, and by the late 1950s the Leonard and Brower families rarely gathered together. Leonard did not always agree with Brower’s tactics, but for a very long time he stood by and defended him. Leonard knew that Brower’s management skills were not strong. “Dave’s weakness was that he was unable to budget either finances or time,” said Leonard. “He was always trying to accomplish too much.” Leonard’s concerns multiplied as the club grew and the financial risks increased. “Dave used to say that the money had always come in and always would and that what we saved today is all that ever will be saved. I used to point out to him yes, but if we had gone bankrupt ten years ago, we wouldn’t be here to fight the Grand Canyon and the other battles at the time.”

61 Leonard worried that Brower could bankrupt the club.

Brower blamed himself in part for the fissure with Leonard. He agreed that there were too many arguments over money. During one board meeting, long before the situation heated up and the break occurred, he was arguing that membership dues would come in and that the club would be financially healthy.

“All we’re trying to do is protect you,” Leonard told him.

“You protect me with the back of your hand,” Brower responded in what he later said was a very abrasive manner. “It really cut him,” he added. “His face just fell. It was quite a shock to him that I would say something like that. It kind of shocked me that I had said it, but I was upset. I would get upset at some of the meetings.”

62The break with Adams was even more emotional and more wrenching. For years, Adams had served as Brower’s confidant. Brower had always believed that he could confide all of his fears and frustrations to Adams. “He had been sort of my father confessor,” he said. “I would take all of my troubles to Ansel.”

63 Adams in turn had staunchly defended Brower. He privately wondered at times if Brower were mentally stable, but he would tell friends that Brower’s only problem was that he was overworked. He seemed tired and, Adams said in one letter in 1959, too sensitive to criticism.

64By late summer in 1966, Adams warned Brower in a letter that he needed to change if he wanted to continue running the Sierra Club. He told him that his extreme reactions to criticism had to stop. Brower was far too paranoid far too often, said Adams. He had a “sense of persecution,” an attitude that was totally baseless. Adams said the solution was up to Brower, that he needed to calm down, but if he did not, he might be fired. Adams told Brower that he truly believed in him and that he was writing because he wanted Brower to keep up the good work in the same position as executive director.

65Two months later, after Brower had not responded. Adams tried again. He feared that Brower now considered him an enemy, part of the old guard, a conservative. Far from it, Adams told Brower, but he added that Brower was often dictatorial and would bypass the board, the Executive Committee, and the Publications Committee. He pleaded with Brower to be more diligent. He said that he was not exaggerating in warning that on the present course Brower was headed for disaster.

66Brower and his supporters would long espouse another reason why Adams “turned on” Brower: jealousy. Brower often described making a remark at a Sierra Club board meeting shortly after two of Porter’s books had been published, which might have produced such a feeling in Adams. “I made the tactless remark in the presence of the directors, including both Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter, that Eliot Porter was our most valuable property,” he said. “I’m sure that offended Ansel no end.”

67 Brower mentioned this comment so often that it gained credence with others.

Clearly, the relationship between Porter and Adams was complex. They were both colleagues in the same field and rivals because they espoused two different approaches. Wayburn believed that Adams never could warm to the color photography in the later books. “He felt that they were too expensive, and from a photographic standpoint he was a black-and-white man,” said Wayburn.

68 But Wayburn dodged the question whether Adams was so jealous that he would turn against Brower. It defies common sense, however, to believe that Adams would feel and react this way. What is clear is that when Adams finally did take a public stand against Brower, it was fueled by vitriolic anger and emotion. It shocked Brower.

In the meantime, Brower was being called on to defend one of the nation’s greatest natural shrines, the Grand Canyon, from his greatest enemies, Floyd Dominy and the dam builders. To win, he would have to gather all of his resources and mount the greatest conservation campaign of his career.