As Rae sat in his tent surrounded by the pitiful remnants of the Franklin disaster, he had a tough choice to make. Should he head back to Britain as rapidly as possible to let the waiting world know that he had discovered Franklin’s fate, or should he wait another winter in Repulse Bay and visit the site of the tragedy the following spring? Rae chose the former course because others were searching for Franklin far to the north, and he felt a responsibility to get word to them as quickly as possible so that no additional lives would be put at risk.

On August 4th, 1854, the ice cleared and John Rae sailed from Repulse Bay. On the 21st of September, he sailed from York Factory aboard the HBC ship Prince Rupert, the vessel that had accompanied him on his first voyage to the wilds of Canada twenty-one years before. In mid-Atlantic they encountered a violent storm that ripped the sails and nearly washed the lifeboat away. But that was nothing compared to the storm that awaited Rae in London. It would be much worse than anything he had faced in the Arctic wilderness.

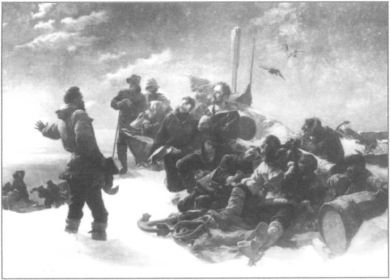

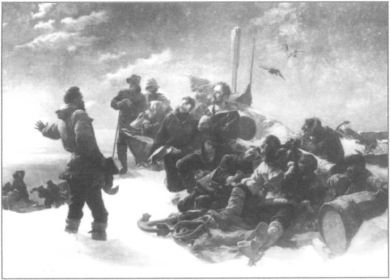

Franklin’s men had been lost unprepared and without hope in a barren land.

The storm Rae was sailing unwittingly towards was triggered by one short sentence in the report of his discoveries that he sent on ahead. It talked of something the Inuit had told him about the camp of dead men they had discovered. It read: “From the mutilated state of many of the corpses, and the contents of the kettles, it was evident that our wretched countrymen had been driven to the last resource—cannibalism—as a means of prolonging existence.”