Adaptation is the catalyst to balance and tranquility. Relationships are always in motion. Successful ones adjust; unsuccessful ones rigidly polarize or just drift apart. In nature, feedback is the mechanism that makes adaptation possible. We call it the acumen of adaption.

Cows lie down long before a storm appears; cats disappear to a quiet corner. Dogs sense variations in barometric pressure, smell changes in the air, and know to get prepared for a tornado. Elephants feel the vibrations of an impending earthquake long before buildings start to topple. The 2004 tsunami that killed thousands of people in Asia killed few wild animals because of their early warning wisdom made possible by feedback. All these examples illustrate the capacity of animals to read environmental feedback in order to adapt and thrive.

Like the weather, customers are constantly changing. It takes feedback to adjust and thrive. The Internet has made the world smaller and faster, accelerating the change process. Today’s fad quickly becomes tomorrow’s antique. Without perpetually updated customer acumen, the covenant gets out of balance and we wake up one day surprised by how much the customer has changed—and we completely missed it! Amazon.com was surprised, for instance, when a computer hiccup on Friday night caused gay and lesbian books to be deemed pornographic and thus excluded from their offerings. By Monday morning Amazon.com got a wake-up call about the importance of monitoring customer feedback over the weekend. A few bloggers had mobilized thousands in protest.1 Had Amazon had a way to rebalance the service covenant early Saturday, they could have completely avoided a PR barn burning.

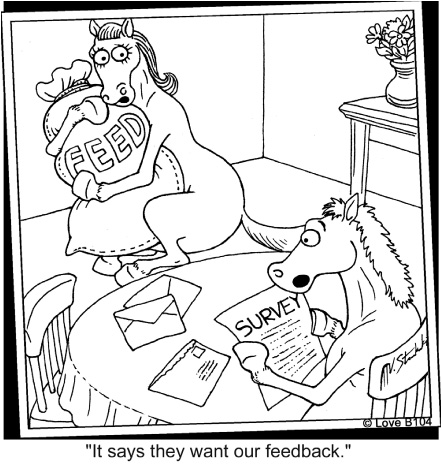

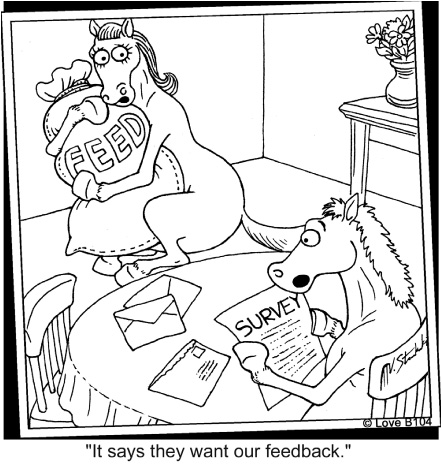

Customer feedback comes in many forms. One type might be gained from examining history. Customer forensics teaches a lot of lessons from the past that can be beneficial in adjusting the present to keep a service covenant strong in the future. We will call this type of feedback “Something Old.”

Real-time feedback ranges from simple devices like asking “What is one thing we could do to improve your experience?” to highly complex means of getting customer evaluation—their assessment of service performance. This is the type of information on which most organizations focus. The good news is it is current; the bad news is that it often can be misinterpreted if not examined with a larger context. We tag this type of feedback “Something New.”

The third type of feedback is customer intelligence derived from a myriad of secondary sources. Reading an article about one of your customer’s plans to downsize might change the tolerance you show for late payments. A study done by your industry association concerning the future of whatevers might suggest a more proactive stance on keeping customers informed. We label this type of feedback “Something Borrowed.”

You already know where this is going! The last category is “Something Blue.” This includes a careful examination of customer complaints and service breakdowns. It could also include asking frontline servers about the things customers seem most anxious about or require more than usual explanation about. All can be information that signals a change in customer requirements.

There are many ways to use customer forensics. The Acme Company (obviously not their real name) uses customer forensics on lost customers, probing for reasons that might disclose lessons learned. When a large customer deserted Acme for a competitor, Acme “deputized” four employees to be service detectives. They sorted through records and interviewed customer contact people. They finally hit pay dirt when one of their security guards solved the mystery: when leaving one of their district offices the customer had complained that his last shipment containing time-sensitive material had arrived one day late, dramatically reducing its usefulness to the customer. So Acme added a question to their order-entry process that determined if “time of delivery” was merely important or absolutely critical. They also added security guards to their list of key sources of customer intelligence. Acme ultimately won back the lost customer.

We were assisting a large construction company with customer forensics on an important, and particularly difficult, customer who had yanked his business from the company in anger and frustration. One of the goals of the customer forensics effort was to equip our client with tools for future customer intelligence efforts. While sifting through correspondence between the departed customer and the construction company, their marketing director suddenly commented, “We have given this poor customer plenty of reasons to keep him up at night. This was a uniquely bad connection. If we had changed the connection early we could have changed everything.”

The comment triggered a renewed look at the data—not as evidence of anger, but as examples of fear. Remember: anger is a secondary behavior and a cover for the fear underneath. The fresh interpretation prompted a deeper, richer understanding of the factors that signaled the customer that his construction project was in jeopardy. Without the project, his business was at high risk of bankruptcy. Without his business, his upwardly mobile wife would likely leave him. With a history of heart problems, such a chain reaction could threaten his life. Thus, his outbursts of anger were actually a cover for his fear-laden cries for help—all misinterpreted by the construction company as simply the grumblings of a high-maintenance customer.

Forensics help solve the mystery of a departed human; customer forensics help solve the mystery of a departed customer. Exits have many meanings. Some are legitimate churn, unrelated to service disappointments; some are at the receiving end of poor service. Unless it happens to be a case of “good riddance,” deep understanding of the departure can help prevent loss of valued customers in the future.

We are both fortunate to have been married a very long time. Like all important relationships, our respective marriages have had their ups and downs, leading us to seek opportunities for more than usual candor. The pace of managing dual, fast-paced professional careers with typical family challenges can work counter to the late-at-night, no-kid-gloves honesty we desire in our marriages.

A week-end couples retreat taken by one of us assigned the couple to write down the limitations each partner saw in the other and then read the list aloud. Such an exercise, done properly, can have a sobering effect. It created a new appreciation for Ted Levitt’s Harvard Business Review article comparing a quality customer relationship with a marriage: “The sale consummates the courtship, at which point the marriage begins. The absence of candor reflects the decline of trust and the deterioration of the relationship.”2

Getting real feedback real-time starts with viewing it like that marriage enrichment exercise—as a valuable tool for insight that can clear up potential blind spots and update understanding of the needs, expectations, issues, and hopes of the ever-changing customer. The means of input are many. Below are seven methods for getting input that we have found to be both simple and fruitful.

Scouts see a lot, hear a lot, and know a lot. Yet they are probably the most under-utilized source of brilliance about what customers really value. Scouts are the frontline people who interact with customers ear-to-ear, face-to-face, or chat-to-chat. It is important for scouts to share their insights and stories about the good, the bad, and the ugly. Invite your organization’s leaders to listen to customer phone calls or ride in the field with frontline servers with the intention of learning, not critiquing. Then, create a way for the collective learnings to move upstream to senior leaders, as well as into the hands of those who can provide a timely response. The more customers see improvement based on their input, the more they share. The more frontline employees are asked for their feedback, the more they listen to and learn from their customers.

Most employees are customers of their own company. As such, they can be a rich source of information about service experiences. Additionally, they talk with neighbors who vocalize praise and protests about the service they receive. This valuable conduit can be an abundant source of feedback. Employees with a company nametag can also serve as a channel for customer feedback simply by standing in the grocery-store line. Smart organizations create forums that enable employees to share their insights from these casual encounters.

John Longstreet, while general manager of the Harvey Hotel in Plano, Texas, held quarterly focus groups with the taxi drivers who frequently transported hotel guests to the airport after their stay. He knew his guests would more likely be candid with the taxi drivers than with the front-desk employee who routinely asked “How was your stay?” The mayor of Santa Clarita, California, holds an annual Hairdressers Luncheon to get input and feedback from people in a role most likely to hear what citizens really think and their suggestions for improving city service.

Many companies have their leaders visit key customers. One company has its leaders visit the customers of their competitors! How do they get in the door? They refuse to turn the meeting into a selling encounter, positioning it instead as a forum to learn what their company lacks that their competitors seem to have. A major hospital had leaders periodically don the uniform of a frontline employee to serve customers personally. These face-to-face learnings are brought back to mahogany row to inform service improvement initiatives.

Customers enjoy service that embodies a sense of agility. Our tolerance for waiting has been dramatically shortened by service providers who make delivery speed part of their core competence. However, customers do not like to feel rushed, especially at the end of their service experience. Ending call center calls with “Is there anything else I can help you with?” signals to the customer that the rep is watching call handle time. We all learned in communications classes what closed questions do to communications. By changing that sentence to an open-ended question (“What else can I help you with today?”) not only alters the experience but it also opens the door for input and feedback while increasing the potential for first-call resolution.

Make it easy to listen to customers by making it easy for customers to contact the organization through email, web-based text chat, toll-free numbers, and more. Many service-focused companies today have webenabled call centers that route, queue, and prioritize incoming email from customers, enabling customer-service reps to handle email and real-time web requests just as efficiently as calls to their 800 numbers. Also, don’t make trying to find an 800 number on your website like a game of “Where’s Waldo?”

Many customers have a good reason for wanting to contact the organization via phone versus sending email or visiting the website’s frequently asked questions (FAQ) page; either they can’t find answers to their questions using those resources or they need more detail and nuance than those avenues provide. Zappos.com puts their phone number at the top of every single page of their website “Because,” says founder and CEO Tony Hsieh, “we actually want to talk to our customers. And we staff our call center 24/7.”3 List your 800 number and email address boldly on every web page. Place large signs in every customer contact area with your toll-free number and email address in bold, and “beg” your customers to call, text, or email. How about a large billboard campaign reminding customers you really do take their input seriously and asking them to call?

Customers often behave in ways very different than they predict. This implies that we must examine more than what they report in an interview or survey. Continuum, a Massachusetts-based consulting firm, was hired by Moen, Inc., to conduct customer research for use in the development of a new line of showerheads. Continuum felt the best way to really understand what customers wanted in a new showerhead wasn’t to ask them via surveys but rather to watch them in action. According to The New York Times, the company got permission to film customers taking showers in their own homes (we just report this stuff) and used the findings in the new design. Among the insights gleaned were that people spent half their time in the shower with their eyes closed and 30 percent of their time avoiding water altogether. The insights contributed to the new Moen Revolution showerhead’s becoming a bestseller.4

A map confiscated from an enemy courier revealed the location of a system of shallow caves, each containing a cache of weapons used to re-supply enemy troops. However, when a wise Army lieutenant sent the captured map to a friend he knew could provide a deeper assessment of the terrain, he learned that each cave was located on a similar site—same type of soil, same topography, same elevation. Checking other areas like the cave sites produced another major discovery: there were many more caves not marked on the map that contained even larger collections of weapons.

The customer intelligence version of the captured map can be productive in unearthing valuable information about customers. The security guard’s assessment of the demeanor of a departing key customer can sometimes be more instructive than forty focus groups and sixty surveys. Talking with a customer you lost last year might be more helpful than talking with the one you acquired last week.

Acquiring customer intelligence is an intentional effort to understand the customer. This search is typically combined with known socioeconomic, demographic, and psychographic data. With contemporary market-research tools, investigators can know the specific buying preferences of a particular zip code. Their forensic techniques can tell you what magazines customers read, the TV shows they watch, and what they name their pets. However, learning such facts is more like searching the caves marked on the map rather than discovering unmarked caves. Understanding customers requires the pursuit of wisdom and insight, not just the quest for information and knowledge.

Customer intelligence is different from market intelligence. Market intelligence teaches us about a segment or group and discerns how they are similar. Customer intelligence informs us about the individuals who make those buying decisions in that market. As you peruse car counts, per capita statistics, and economic projections, it is helpful to remember the words attributed to Neiman Marcus founder Stanley Marcus: “A market never bought a thing in my store, but a lot of customers came in and made me a rich man!”

Knowing what customers are really like starts with the recognition that reviewing the results from customer interviews, surveys, and focus groups is at best like looking in a rear-view mirror. Today’s customers change too rapidly to rely solely on what they reported. Instead it is important to anticipate where they are going. In the words of one infantry captain, “Any military unit can figure out where their enemy is. Victory comes with figuring out where their enemy will be.”

Just as personal relationships have their occasional rough spots, so too will a customer relationship have its ups and downs. If there’s real long-term value in the relationship, both parties will have an incentive to overcome the periodic problems and, through doing so, make the relationship even stronger. In contrast, an absence of candor that causes one partner to gloss over or fail to mention problems reflects declining trust and a deteriorating relationship.

Avoiding complaints, pretending that everything is just peachy (even when you know it isn’t), pretending to assertively solicit customer feedback on the one hand while backhanding the annoying customer for daring to utter a discouraging word on the other are sure signs that the relationship has not achieved enough maturity to weather the candor. That way lies dissolution.

Go to

Staying close to the customer requires never ending learning and update. Customers continually change. Tools #1, 6, and 14 provide extra help on useful ways to increase your customer acumen–focus groups, customer forensics, and surveys.

Accenture’s Global Consumer Satisfaction Survey found that 69 percent of customers have voted with their feet in the past year, moving to a new provider for at least one product or service.5

There are four basic reasons why customers choose to vote with their feet, and go looking for another service provider rather than sticking around and trying to work the problem through with us: they don’t know how to complain or have a way to do it; they don’t want to be made wrong; they don’t believe it will matter; and they worry about retaliation.

A strong, enduring customer service relationship will be founded on clear, open communications, whether the matter at hand is positive or negative. Customers who take the time to bring their problems to us, or offer advice on how we can get better at meeting their needs, are customers who believe we care enough to act on their complaints, not just feel good about their compliments. They’re telling us they still see value in the relationship if, that is, things can get back to a sound and mutually satisfying level. They’re really a golden asset.

Acumen means insight and wisdom. In today’s changing customer world, it is acquired only through continual feedback and current intelligence. The pursuit of feedback serves many purposes. It communicates to employees that the customer is truly important; it telegraphs to the customer that their two-cents-worth really matters; and, for the organization, it keeps the service covenant in balance to maintain a healthy, positively memorable customer experience.

Acumen is a big word with a wide meaning. While the traditional definition is about being smart, it also means shrewdness. Its origin is the Latin word acumere, meaning “to sharpen.” Bestselling author Stephen Covey listed one of his “7 Habits” as “Sharpen the Saw”—his label for continuous learning or, in his words, “the balancing and selfrenewal of your resources.”6 Smart organizations find a myriad of ways to remain smart and shrewd about the ever-changing customer. Growing in a relationship—whether spouse, partner, customer or friend—is vital to growing the benefits of that relationship.

And now, we ride off into the sunset…

The main body of the book is concluding. What follows is an array of resources in a section we call “Flash Drive.” Its intent is to bolster continual learning and renewal.

We hope this has been an insightful (make that an e-sightful!) journey and that the trip has renewed your allegiance to the nobility of service and nurtured your zeal to make customer experiences matter more.

In the face of data overload, cyber-sonic excess, and the grandstanding nature of cynicism, the route to healthy partnerships with customers can seem overwhelming if not impossible. But, we would encourage you to wear your customer challenges like an oyster wears a grain of sand. Be the master choreographer of the customer experience you create. Deliver over-the-top service from your heart, filled with the optimism of a child at the winter holidays as well as the unconditional acceptance of a loved pet. Let it be all about your customer, in word, deed, and symbol.

In this era of the Internet we desperately need partnerships—those neighbor-like relationships that honor service at a caring level. True partners remain loyal through good times and bad, through layoffs and lay-ups, through healthy moments and sickly madness, and through joyful wins and disappointing mistakes. Such relationship commitments start, and continue, with the expression of a partnership orientation: honesty, generosity, curiosity, integrity, balance, and an allegiance to collaboration.

The byproduct of customer partnerships is more than simply loyalty. The deeper consequence is that partnerships foster lives of peace, joy, and contribution. Partnership does not happen solely through good intentions. It starts with the courageous act to invest greater focus and energy on making service a cherished bond, not just an inconsequential business deal. And it starts with a single encounter—your next one.