I probably would have stayed in Little Rock if I hadn’t married a girl from the Northwest. We both wanted to be close to our families, but I’d been away from home for almost ten years. I was used to it. Adeline was not. So that was our first big decision after the war—to settle in Spokane—and I was in a terrific hurry to get there and find a job in the fall of 1945. Everybody knew there were millions of guys on their way home from overseas at that time. You didn’t have to be a genius to figure out what that would do to the competition for jobs in the civilian world.

My oldest brother, Lloyd, beat me home by several months. He was with one of the tank battalions in France until the Army gave him a medical discharge. The Army doctors didn’t know what was wrong with him, and it was years later before we found out that he had leukemia. Lloyd died in 1952. My brother Max got a medical discharge from the Navy. They sent him home with a broken eardrum, from standing around those big guns on the warships a little too long, I suppose. Velton had to

stay in the Army Air Force for another year or so after the war. He was in Tokyo, serving with the occupation forces.1

Civilian air traffic controller Ray Daves, 49, displays a Halloween sense of humor in the control tower at Spokane International Airport, October 31, 1969. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Thanks to Adeline’s connections with the Army in Spokane, I got my first civilian job at Fort George Wright. They hired me to check the pay records for guys who thought the Army owed them more than what they got with their discharge papers. I did the research to prove if they were right or wrong. In the majority of cases I handled, the Army was right. It was not a fun job. I wanted something better, and I found it in the spring of 1946. That’s when I started as an air traffic controller for the CAA.2 No question about it, being a radioman on an aircraft carrier was perfect training for the control tower. I was not at all surprised that so many other civilian air traffic controllers were Navy radiomen during the war. Some of us had more experience with tracking planes on radar than others, but

we all knew how to carry on a conversation with several pilots at once.

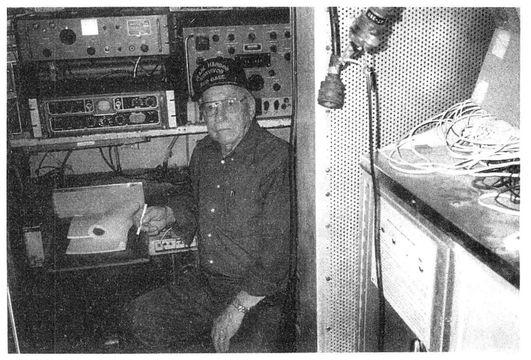

Former Navy radioman Ray Daves, 84, visits the radio room of the restored World War II submarine Cavalla (SS-244), Galveston, Texas, April 2004. (“It’s very similar to the Dolphin’s, ” says Daves.) COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Adeline went back to her old job as a secretary for the Army at Fort Wright. They were glad to have her, but she didn’t stay long. It was her choice to quit working outside the home when we had our first child. Rayma was born in 1946.3 Three years later, we had Janet. She was barely forty when she died of cancer. That was an awful blow to the whole family, especially her husband and children, but the Bible says I’ll see her again in heaven, and I do believe that. In 2007, Adeline and I celebrated our sixty-third wedding anniversary. To me, she is as beautiful as the day we met at the CCC camp in Idaho when I was sixteen. She still has the music box, the compact, the purple velvet bathrobe, and most of the letters I wrote during the war years. We have five grandchildren and five great-grandchildren, so far.

The veterans hospital in Spokane has treated me well. I had

back surgery to fix more of the damage from the accident with the generator at Cold Bay. I’ve also had surgery to remove some precancerous spots on my face and neck. The doctors said I got them from spending too much time in the sun, probably from all those months I was out on the catwalk watching planes take off and land on the Yorktown (CV 5) in the South Pacific. The Navy didn’t issue sunscreen to anybody in the Coral Sea. Other than that, I’m in pretty good health. I’m sure this has a lot to do with the fact that I never smoked while I was at sea. I quit smoking altogether a few years after I got out of the Navy. I haven’t had a cigarette in fifty years.

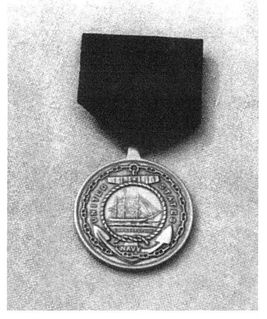

The American Defense Service Medal. All U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine personnel on active duty for any length of time from September 8, 1939, through December 7, 1941, were eligible for this medal. (U.S. Army and Army Air Force personnel who were on active duty for at least 12 months during that period of time were also eligible.) COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION (PHOTO BY TINA McGOVERN).

I bought my first life insurance policy in boot camp. The Navy gave me the option to drop it or convert it to something called twenty-pay life when I took my discharge. All I had to do was keep paying the premium, and after twenty years it would start paying me. Best investment I ever made. Every September for the past forty years or so, I’ve got a check in the mail for $170. I love it. I’ll be eighty-seven in June 2007. I’ve collected thousands of dollars more from that Navy life insurance policy than I ever paid into it.

I retired from the FAA in 1974, but I still copy Morse code.

I have a ten-channel receiver sitting next to the typewriter in my home. About once a week, I sit down and practice typing what I hear. I’m not nearly as fast as I used to be in the Navy, but it’s good brain exercise. And I still like to hunt and fish. Whenever I catch a salmon, I cut that sucker down the middle to see if he’s got the wallet I lost in the latrine on the way to Treasure Island. In the fall, I go deer hunting with some friends along the Canadian border. At the end of the day, we come back to the cabin and play poker all night. I enjoy the game as much as I did in the Navy, but I have never been dealt another royal flush like I got on the Algonquin. I guess that only happens once in a lifetime.

The American Campaign Medal. Eligible recipients included all U.S. military personnel who served for an aggregate period of at least one year—December 7, 1941, through March 2, 1946—within the continental United States. COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION (PHOTO BY TINA McGOVERN).

I would have traveled coast to coast for a reunion with Scoop or Spic after the war, but I never saw either one of them after we parted company at the submarine base after the attack on Pearl Harbor. I did talk to Scoop’s brother. He told me Scoop ended up working for the city of Fresno as an electrical inspector, and that’s where he took up golfing. He was in his sixties when he had a heart attack on the golf course and died. What a way to go. I’m glad he was doing something he loved. His brother didn’t

know how Scoop got his nickname until I told him about the poker games in the barracks at Pearl Harbor. I have no idea what happened to Spic. If he survived the war, I think he would have ended up in one of the technical fields, maybe as a teacher. He had such an analytical mind. Most of my other closest friends in the Navy died in combat.4

The Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal. Most U.S. military personnel who served in this geographic region from December 7, 1941, through March 2, 1946, were authorized to receive this medal. COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION (PHOTO BY TINA MCGOVERN).

I suppose everybody has nightmares from the war. Sometimes I wake up on the floor. Adeline always asks why I’m thrashing around and talking in my sleep, but that particular nightmare doesn’t come with many details. All I know is, I’m inside the Dolphin, and we’re crash-diving. There’s a Japanese destroyer dropping depth charges on us, and the boat is filling up with water, and I can’t get out. Most of my nightmares come from the attack on Pearl Harbor. I’m on the roof of the administration building, the water is on fire, and the air is full of enemy planes and black smoke. I wish I had a nickel for all the times I’ve dreamed about that Japanese pilot. I know he’s dead, but his eyes are open, and he’s coming for me. I try to run away, but I can’t move my legs. I used to wake up screaming from that one at least once a week. It’s been better lately—more like twice a year. I don’t know if the nightmares will ever stop altogether.5

The Navy Good Conduct Medal. This medal was typically awarded to anyone who received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy. (The U.S. Army, Army Air Force, Marines, and Coast Guard issued a similar medal to honorably discharged personnel at the end of World War II.) COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION (PHOTO BY TINA MCGOVERN).

When I first joined the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, there were over a hundred of us in eastern Washington and northern Idaho. In the late fifties, we started getting together for lunch every other month. Our motto is “Remember Pearl Harbor—Keep America Alert—Eternal Vigilance Is the Price of Liberty.” But we never sat around and talked about our memories from December 7, 1941, and we still don’t. For me, it’s just good to be with people who know exactly how I feel about that day. Our chapter’s membership is down to about twenty-five now. In 2005, we started meeting every month instead of every other, and we don’t reserve the banquet room in the restaurants anymore. Six or seven of us is considered a big turnout these days. I’m sure that the rest of the chapters around the country are getting smaller, too. In 2008 our youngest member was eighty-three.6

I never thought anything like the attack on Pearl Harbor could ever happen again, but it did. September 11 hit me like a mule kick in the gut. I could not hold back the tears. I had flashbacks to Pearl Harbor, and all that fear and anger came flooding through me like it happened yesterday. I got on the phone, called some of the other Pearl Harbor survivors and a few close friends from my church. We prayed for the people who survived the attack on the

World Trade Center and the Pentagon. I’m guessing they will have nightmares for the rest of their lives, too.7

I did not cancel my plane reservation to Hawaii after 9/11. It made me more determined than ever to make it to the sixtieth anniversary ceremonies at Pearl Harbor in 2001. I didn’t really want to see my friend George Maybee’s name carved in stone on the Arizona. For all those years, I think I had myself talked into believing that maybe he survived. It was hard to face the fact that he did not. I didn’t cry until somebody handed me a bouquet of roses. One by one, I dropped them all in the water for George. The Arizona was his grave.8

The World War II Victory Medal. All U.S. armed forces personnel (as well as those of the Philippines government) who were on active duty at any time between December 7, 1941, through December 31, 1946, were eligible for this medal. COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION (PHOTO BY TINA MCGOVERN).

After the ceremony on the Arizona, I saw a small group of Japanese men on shore. They appeared to be about the same age as me. I was told that these were some of the pilots and gunners from the six carriers that attacked us. I guess they needed to come back to Pearl Harbor, too. No one introduced me to them. If they had, I would have been cordial. Sixty years ago, Japan was the U.S. Navy’s most powerful enemy, and we would have killed each other on sight. I’m glad that’s History. Japan is one of our best friends and most powerful allies in the whole world

now. I also know that the attack on Pearl Harbor was not the biggest battle of World War II. Far from it. But to me it will always be the worst, because it was the first, and I was there.

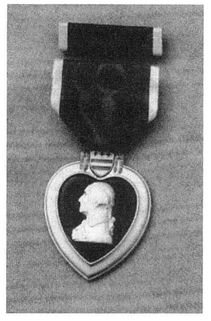

The Purple Heart Medal. Anyone in the U.S. armed forces who was wounded or killed by enemy action, died later from wounds caused by enemy action, or sustained illness or injury while a prisoner of war is eligible for the Purple Heart, the nation’s oldest military medal. At least 800,000 Purple Hearts have been awarded to World War II veterans or their next of kin to date. COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION (PHOTO BY TINA MCGOVERN).

I have never met a Pearl Harbor Survivor who looks forward to December 7 of any year. None of us enjoy recalling what happened that day, but my chapter considers it a duty and a privilege to show up whenever the schools invite us to their assemblies. Sometimes the teachers ask us to come into the classroom and tell the students what we saw. I don’t enjoy that either, but I do it anyway. The kids are always very respectful, and they ask a lot of questions. I tell them what I remember, I tell them I was scared to death, and I tell them not to call me a hero. I’m a survivor, and that’s all I ever claimed to be.

I just hate it when somebody asks me how many enemy soldiers or sailors I killed during the war. I don’t know how to answer that one. I did not pull the trigger on the machine gun on the roof of the administration building at Pearl Harbor. I did locate targets for the Yorktown’s pilots, and, yes, I painted my mother’s name on some of the bombs and torpedoes that our planes used to sink all those Japanese carriers in the Coral Sea and at Midway. But it wasn’t my hand on the release lever that dropped them. And, yes, I flew a lot of search-and-destroy missions in the Aleutian Islands,

but I never found a Japanese sub crew in my gunsights. So, in that sense, I could say that I never killed a single living soul. But that’s not really the truth, and anyone who was there knows exactly what I mean. Every one of us knows that we were partly responsible for killing hundreds or thousands or millions, depending on where you draw the line between direct and indirect action. It’s pretty hard to explain that without telling the whole story of the war.9

Pearl Harbor survivor Ray Daves, March 2008. COURTESY OF ANGELA V. DAVES-BOYETTE.

I never expected any medals from the Navy, and I never filled out any paperwork to get one. But thirty or forty years after I took my discharge, I got a package full of medals in the mail. I have no idea how that happened. I received another medal during the fifty-fifth anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. I didn’t ask for that either. In 2001, I got a letter from President Bush. He was out of office then—his son was in the White House—but it was still pretty nice of him to sit down and write to an enlisted man. I didn’t always agree with his politics, but I always respected the first President Bush because he was a World War II veteran, same as me. I never met the man, but I know that he was

a carrier pilot. That’s what I wanted to be. I have always envied the guys who got to fly more than I did in the Navy.

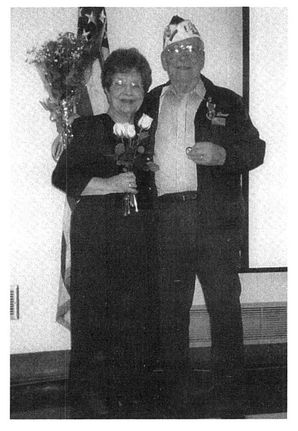

Chief Radioman Ray Daves, 23, and Adeline Bentz, 24, Euclid Baptist Church, Spokane, Washington, February 26, 1944. (The “dress blue” eightbutton jacket indicates chief petty officer; white sparks below eagle on left sleeve indicate specialty is “radioman”; diagonal stripe indicates at least four years’ service in the U.S. Navy.) COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

My last medal did not come in the mail. It was handed to me personally, by the commander of the Navy and Marine Corps Reserve Center in Spokane on December 7, 2002. That was the sixty-first anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. At the end of that ceremony, all of the Survivors were called to step forward. There were over twenty of us that day, and television cameras everywhere. I was embarrassed when the commander called my name. I still have the scar from the shrapnel wound, but I never thought I’d get a medal for it. It would have meant more to me if I’d got the Purple Heart when I was younger. I think that and all the other medals I received from World War II are more important to my grandchildren than they ever were to me.

After a while, you get so you can push it all so far back in your mind, you can almost fool yourself into thinking you don’t have any memories. For a long time, I refused to admit that I did. I was afraid of what people would think if I got all teary-eyed,

like I am now. That’s kind of embarrassing, too, but in a way it’s not. My friends were brave men. They did what had to be done, and they deserve to be remembered as heroes. I don’t understand why they got killed and I survived. I still feel guilty about that, sometimes, but I’m not sorry for telling what happened to them and to me during the war. It’s a relief to pass it on. I don’t have to remember anymore.

Ray and Adeline Daves, December 7, 2002, following presentation of the Purple Heart medal be earned at Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. COURTESY OF CAROL EDGEMON HIPPERSON COLLECTION.