BASIC TRAINING

Mid-April–August 1939

The first thing they did was cut off all our hair. Then we got our uniforms. The dress whites and dress blues were for Sundays and special occasions. Those had stripes around the collar and two stars in the back. The regular or “undress” uniform—whites or blues—were plainer, for everyday. None of the pants had zippers. Instead, they all had this square flap across the fly, and thirteen buttons. The guys issuing the uniforms told us this was for the thirteen original colonies. If you wanted bell-bottoms, which everybody did because flared legs were the style, you had to take them to a tailor and pay for the alterations yourself.

There was one piece of the uniform everybody hated, and that was the leggings. We were apprentice seamen—lowest there is in the Navy—so we had to wear them every single day. Leggings were these stupid-looking white canvas things that snapped around your pant legs. I have no idea what purpose they served, except to show we were the scum of the base for the next sixteen weeks.1 Oh, we had a lot of choice words for those

leggings. Some guys called them “boots.” Maybe that’s why it was called “boot camp.”2

We couldn’t go to bed at night until we scrubbed our leggings with a brush in a bucket full of soap and water. And every morning before breakfast we had to do the same with our hammocks. We hated those, too. I never understood why we had to sleep in hammocks.3 Maybe it was to teach us discipline, but they were torture. It was like sleeping on a banana. If you heard a big thump in the night, it was some poor guy that made the mistake of turning over in his sleep. You had to stay on your back or the hammock would flip upside down and dump you on the floor.

There were about a hundred of us in Company Nine; our barracks were located in what they called the John Paul Jones section. I didn’t know who John Paul Jones was.4 I thought he was the guy that invented marching drills, because that’s what we did, every day, for hours at a time. The marching field was called “the grinder.” Maybe it was supposed to grind the civilian out of you. The Navy had a lot of weird terms for ordinary things like that. Stairs were not stairs; they were “ladders.” Floors were “decks,” and right is “starboard,” and left is “port,” and it just goes on and on. I felt like I was learning a foreign language. There was no sense trying to figure it out. After a while you just get used to speaking “Navy”; you follow orders, and you don’t ask questions anymore.

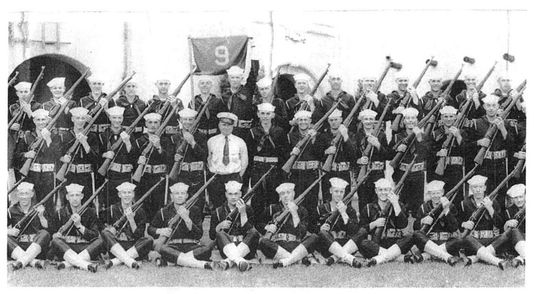

U.S. Navy recruits (also called apprentice seamen) in Company Nine, Naval Training Station, San Diego, California, with John Paul Jones barracks in background, April 1939. Seaman Third Class Ray Daves, 18, is seated, front row, second from right. “Dress blue” uniforms have white markings. The “seaman’s stripe” around right shoulder seam indicates sailor is “unrated,”not yet trained in any Navy specialty. [This is a portion of the original 8″x 39″ print that shows the entire company.] COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Marksmanship was pretty fun. I’d done a fair amount of squirrel and quail hunting with my grandpa’s shotgun, but the Navy issued rifles. Ours were Springfields, thirty-ought-sixes. The shells were about as long as your index finger and as big around as your thumb. It was not an automatic, or even a semiautomatic weapon. Everybody said it was probably left over from World War I. I liked it for target practice, though.5 It even had a bayonet attachment, which was kind of cool. The blade was about twelve inches long and sharp as a razor. We kept that in a leather sheath, clipped onto our ammunition belts.

I only remember one time when we actually used our bayonets, and that was on the dummies—gunny sacks stuffed with straw. When we went out to the shooting range that day, I saw them hanging like a bunch of scarecrows on a line about chest high. The instructor told us to snap the bayonet on the end of our rifle and take turns running up and stabbing the dummies. We had to fire one round before we pulled the blade out. He said that would shatter the enemy’s bones and make it easier to withdraw your bayonet from the “body.” So we all did that, several times apiece, but there was a lot of mumbling up and down the lines. Finally, one of the guys in my company spoke up. He actually had the nerve to ask the question all of us were thinking, which was, “Why do we have to learn all this Army stuff?” The instructor said, “Sailor, if this country goes to war and your ship gets sunk, you might find yourself on a beach in enemy territory.” End of discussion. Well, we didn’t think there was ever going to be a war, and we still thought the bayonet drill with the dummies was lame.6

There was also a swimming pool. It looked Olympic-sized to me—about fifty meters long—and we couldn’t graduate from basic until we could swim the length of that pool three times, without stopping. Well, my dad was right. I really was a rotten swimmer. Would you believe it, I was the only one in my company who did not qualify on the first try. So, every day after that I had orders to report for swimming lessons. The guy in charge of the pool was a boatswain. It’s pronounced bo-sun. Don’t ask me. That’s another one of those Navy words. Anyway, this boatswain was a chief petty officer, which is like a master sergeant in the Army, and he was really old, like in his forties. Every time I showed up for another session with him, he said, “Boy, I’m gonna teach you to swim if it kills you.” He had this long pole with a net on the end, and whenever he caught me dog-paddling, he would reach out with that pole and push my head under the water. I really think he would have liked to drown me if he thought he could get away with it. That chief boatswain was the second meanest guy I ever met in the Navy.

The first meanest was our company commander. He was a chief petty officer, too, but his specialty was torpedoes. You could tell by the insignia on his sleeve. Now, why the Navy would put a chief torpedoman in charge of training a hundred new recruits, I have no idea. I just remember swearing to myself, if I ever got to be a chief of anything in the Navy, I would never be as mean as he was. The man never spoke to us in a normal tone of voice. He just yelled, all the time. One morning, we were all lined up on the grinder, and the chief hollered out, “Davis! Step forward!” Well, we did have a guy named Davis in my company, but the chief wasn’t looking at him. He was looking at me. So I stepped forward. He got right up in my face and started chewing me out for something I had not done. One of the older guys finally spoke up and told him I was “Daves,” not “Davis.” That chief petty officer never once admitted that he’d made a mistake, and he never told me he was sorry. But he did call me into his office a few days later and told me I was now one of his four apprentice petty officers. Maybe that was his way of making it up to me.

Apprentice petty officer was sort of like squad leader in the Army, I think. We got no extra pay, and the title did not exist outside of boot camp. All I got was a square knot insignia on my sleeve and a whole lot of teasing. Everyone called us “the square knot admirals.” It was now my job to enforce lights-out in the barracks by ten o’clock. Real big deal. I was also supposed to report anybody who broke the rules. I never did, and neither did the other apprentice petty officers, as far as I know. Oh, I suppose if a guy came back from a night on the town with his trousers on backward, he might have been reported, but nobody in my company ever stepped that far out of line. We didn’t have much free time to begin with, and there was very little horsing around, because we were all so serious about being in the Navy. Most of us saw it as our one and only chance to learn a trade. We were always talking about what great jobs we were going to get when we got out of the Navy.

The only times I remember just hanging out with the guys in my company was on Sunday afternoons, after church. Church attendance was required in boot camp. I didn’t go around checking everybody else’s dog tag, but if they were anything but Christian, they were out of luck. The only choice we had was Catholic or Protestant. The same Navy chaplain conducted both, one right after the other. I always went to the Protestant service. We had to march to the chapel on Sunday, the same as everywhere else in boot camp. After church, I usually walked over to the channel and watched the ships coming and going in the harbor. I’d never been on anything bigger than a rowboat, so I was just fascinated with the idea of going to sea on a warship.

On the way back to the barracks, my friends and I would stop for a Coke or an ice cream cone at the “gedunk.” This was what they called the little convenience store on the base. It was where you went for stuff like newspapers and shaving cream and snacks. What caught my eye were all the photos of the ships on the walls. Some were just postcards, but they had bigger sizes, too, and they were all for sale. That’s what I was staring at the first time the guy at the gedunk counter asked me if I’d come for

my “pogey bait.” I didn’t know how to answer that until he told me it meant “candy.”

Pogey bait was not one of the Navy words listed in The Bluejackets’ Manual. Almost everything else was. We each got one of those books, and we were supposed to read it on our own in our spare time. It was like going through the Bible; I read a few pages every night. It was mostly rules and regulations. The classroom lessons were a lot more interesting. We got those every day, for about an hour after lunch. That’s where they taught us stuff like the definition of a man-o’-war. That’s a warship; it carries offensive weapons. All the other types of ships, like minelayers and repair ships—they carried weapons, too—but only for defense, like antiaircraft guns.

I also remember learning the Navy’s system for naming all the different types of ships. Some kinds of ships were named after birds, some were rivers, and some were stars. There were about a dozen different name categories like that. If you memorized them all, you could tell what kind of ship it was, just by the name. The only name categories I ever learned were the five types of warships: destroyers, cruisers, aircraft carriers, submarines, and battleships. Battleships were states, cruisers were cities, and submarines were fish. Aircraft carriers were named after famous battles or ships in American history, and destroyers were people. The instructor said the Navy might even name a destroyer after one of us. All we had to do was die like a hero in battle. That got a laugh. Nobody in my company believed that was very likely.

The only other classroom lesson I really remember was the VD movies, and, man, was that ever an eye-opener. Me, a dumb farm kid from Arkansas, I didn’t even know what a venereal disease was, much less how you caught one. But, you know what, it was news to a lot of the city boys, too. I could tell by the expressions on their faces. Most of the guys in my company were under twenty-one. They didn’t know any more about gonorrhea and syphilis than I did. The Navy had a very strict rule about that stuff: If you had any reason to believe you were exposed to an STD, you were supposed

to report to the nearest sick bay, sign your name in the doctor’s book, and get this medicine that you spread on your private parts. If you showed up with any symptoms after that, you were in the clear. The Navy doctors would just treat you and send you on your way. But if you came down with any of those diseases and your name was not in the book, you were in big trouble.

A week or two before we graduated from boot camp, an officer came into our classroom and read off the list of trade schools. After each one, he asked for a show of hands. Most of the guys in my company wanted to be mechanics or electricians. Nobody—I mean nobody—asked for torpedo school. No use for that skill outside of the Navy. I was one of five or six that raised our hands for communications. After that, you had to say which kind: flags or radios. Of course, I picked radios. I had to take the aptitude test, which was to put on headphones and listen to a series of tones. The object was to see if you could tell which tones sounded shorter, like the dots in Morse code, and which were a fraction of a second longer, like dashes. This was easy for me, because I already knew Morse code. I learned it in Cub Scouts. That was how we sent messages back and forth between the tents when we were supposed to be asleep. We usually did it with flashlights, but you could tap it out with sounds just as well.

On graduation day in August, we all got promoted to seaman, second class. That was a huge pay increase, all the way from twenty-one to thirty-six dollars a month, just like that. And most of us also got reclassified as “strikers.” I was very happy when I found out I was now a striker radioman. As it was explained to me, this meant I was accepted into radio school, all right, but, for whatever Navy reason, I had to go to sea for a while first. I was okay with that, especially when I saw the ship’s name on my orders. It was a man-o’-war. I ran right over to the gedunk and bought the biggest picture they had of that ship and mailed it home to my mother. I didn’t know who Flusser was, but he must have been some kind of a hero.7 The Flusser was a destroyer.