THE SUBMARINE

December 24, 1941–February 3, 1942

I did not know where the Dolphin was going until we cleared the channel out of Pearl Harbor. That’s when the captain picked up the microphone and spoke to the crew. I didn’t need a loudspeaker to hear him, because the command center was less than ten feet from the radio room. There wasn’t even a door between us. If the senior officers didn’t want the radiomen to know what they were saying around the periscope, I think they would have had to pass notes. But the captain’s mission announcement was for everybody. He told us we had orders to spy on the Japanese bases in the Marshall Islands. 1 I didn’t know where that was, other than somewhere in the South Pacific. He also said that we would attack any enemy ships we found along the way, especially the ones that might be bringing soldiers to Hawaii. There was still considerable worry that the Japanese might try to invade and capture our base at Pearl Harbor.

The rules of engagement were “unrestricted submarine warfare.” I didn’t get the significance of that until we started talking

among ourselves. The Dolphin’s communications officer explained to all of us radiomen that any ship flying a Japanese flag was a target, including their supply ships. They could even be civilian-owned cargo vessels, like our Merchant Marine. The Japanese called them “maru.” We all knew these kinds of ships were mostly unarmed, totally defenseless against a submarine, and I remember thinking, Whoa now. Wait a minute. You mean we’re actually going to kill people? Hundreds, maybe thousands of them? On an unarmed ship? The more we talked about it, the more it bothered me. Finally, somebody said, “Well, yeah. But look what they did to us at Pearl Harbor.” And that’s how I got past it. From then on, I knew I was going to follow orders. It wasn’t my job to press the button that fired the torpedoes, but I’m sure I would have done that, too. We never talked about it again.2

I was one of six radiomen on the Dolphin. Submerged or on the surface, we spent most of our time trying to locate enemy ships. I didn’t have much experience with sonar, but I understood the principle. Sonar was just a variation of a radio transmitter. I never actually saw the device because it was underwater, hanging like a gallon milk jug from the belly of the submarine. When we turned it on, it sent out a constant radio signal for about a hundred miles in all directions. Anything that was big and thick enough to bounce the signal back to us showed up in green lights on a screen in the radio room. It made a pinging sound on the headphones, too. The closer the object, the louder the ping, but you couldn’t tell if the ship was friend or enemy without raising the periscope. Sometimes it wasn’t a ship at all. It was a whale. It took a lot of practice to hear the difference. Whenever I said, “I have a ping, Sir,” one of the officers—sometimes the captain himself—would come over and put on the headphones. The radiomen thought that was hilarious. The senior officers on the Dolphin had even less experience with sonar interpretation than we did.3

There was almost no sensation of movement when we traveled underwater. It was like living and working in a building with no windows, and we didn’t have much to do besides eat and

sleep between shifts. We played a lot of board games—mainly acey-deucey—to pass the time. It’s similar to backgammon: you just shake the dice and move your pieces up and down the board. We had acey-deucey and chess tournaments pretty much around the clock on the Dolphin. The highlight of everybody’s day was when we surfaced at night. Anyone could go outside for some fresh air after dark, but never all at once. In case of emergency—if we’d needed to crash-dive for some reason—it would have taken too long to get everybody back inside. The hatch was only big enough for one man at a time. We took turns going outside in small groups of ten or twelve, all night long.

The first few nights were actually quite relaxing. As soon as we were on the surface, the radiomen checked in with headquarters. We could not send or receive any radio messages while we were submerged. After that, the captain let us tune in to a civilian radio station. If we picked up one that was playing big band music, we put it on the loudspeakers. Everybody wanted to hear the latest from Benny Goodman—he was the King of Swing—but some guys thought Glenn Miller’s band was the best there was.4 I never got into those debates, because I frankly didn’t care what was on the radio when it was my turn to go outside. I usually just stood by myself and looked at the stars. In the warm night air, with no other ships around, you could almost forget that we were at war.

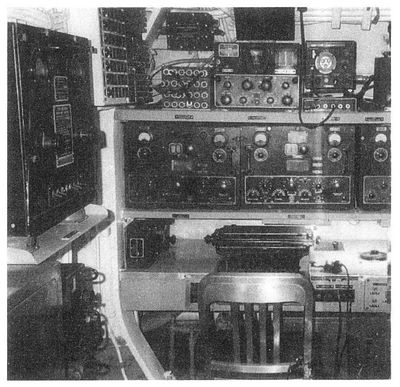

The radio room of a World War II–era submarine contained both transmitters and receivers. The key used to tap Morse code through transmitter is at right of typewriter; headphones for listening to incoming messages are hooked to right of chairback. COURTESY OF C. E. “TED” AND MARIE T. WIGTON COLLECTION.

There were about sixty of us on the Dolphin. It felt more like six hundred when everyone was inside. If you met somebody coming or going, you had to turn sideways and suck in your stomach to let the other guy get by. I began to understand why I hardly ever saw the sub crews inside the barracks at Pearl Harbor. They were always outdoors, around the pool or on the tennis court, even when it rained. I could also see why the Navy didn’t make them live on their subs when they came into port. But I never got why they kept referring to the Dolphin and all the other submarines as “boats.” The way I learned it in boot camp, a boat was something small enough to carry aboard a ship. Well, the Dolphin was nearly as long as a destroyer, and some of the newer submarines were even longer than that. I just chalked it up as one more way of saying sub crews were different from everybody else in the Navy.5

I didn’t know what to think when we started having so many mechanical problems. First it was leaks, and they weren’t just little drips here and there. I’m talking sprays. The boatswains had to run around and patch nearly every pipe and joint just to keep us from sinking while we were submerged. When the fathometer malfunctioned, the captain had to guess how deep we were. The radiomen were guessing, too, because the Dolphin’s radio antenna kept shorting out. We were never sure if our nightly reports to headquarters were getting through. It’s probably a darned good thing that we didn’t locate any enemy ships during that first week out of Pearl Harbor: The captain had too many other problems to deal with.

Every time I turned around, the captain was in conference with the COB, the Chief of the Boat. The COB was the senior enlisted man on the Dolphin. Not only was he the oldest chief petty officer, he was also a boatswain, which probably had something to do with his short temper. And, not only that, the COB was what they called a “plankowner.” He’d been on the Dolphin since it first came into service. If anyone knew what was wrong and how to fix it, it was the COB, and I heard him tell the captain to turn around and go back to Pearl Harbor for repairs. But the captain was also taking advice from the Executive Officer, his second in command. The XO didn’t think the mechanical problems were that serious, and even if they were, we should complete our mission or die trying.

I felt sorry for the captain. He was caught in the middle between the COB and his XO, and I could tell that the stress was beginning to get to him. It was his first wartime mission, too. Personally, I agreed with the XO, and so did all the other enlisted men. We didn’t have a big meeting or take a vote, and nobody asked our opinion. We just talked it over in small groups. As far as I know, the COB was the only one who thought the captain was making a big mistake when he decided to continue the mission.

Shortly after New Year’s Day, the off-duty conversations switched from leaks and mechanical malfunctions to pollywogs. Anyone in the Navy who had never crossed the equator was a pollywog, and there were about ten of us on the Dolphin. War or no war, leaks and all, this called for a ceremony. The Navy was real big on tradition. The older men tried to scare us with stories of what happened to them when they crossed the equator. Some said they had to take off all their clothes and walk past a line of guys with paddles. So, yeah, you could say I was a little nervous when the navigator said we were about to “cross the line.”

The officers went outside first that night. We had to wait until they called for us, one by one. When it was my turn to climb the ladder, I didn’t see any guys with paddles. All I saw were the officers, the COB, the head cook, and a dirty-looking pail with

the word “worms” painted on the lid. Somebody said, “Kneel,” and they tied on a real thick blindfold, so big it covered my nose, too. It smelled like dirt and dead fish. The captain rattled off a bunch of mumbo jumbo about how crossing the equator is when you meet King Neptune in his mysterious, watery realm. It was pretty funny until he got to the part where he said, “and a pollywog’s gotta eat worms.” The cook told me to “open wide and chew ’em up real good.” I should have known it was just that old trick from science class, the one where you close your eyes and hold your nose and try to tell which is the apple and which is the onion. I guess I forgot that lesson. I really believed I’d just eaten a big glob of slimy worms. I didn’t know the bucket was full of cold, cooked spaghetti until they took off the blindfold. I acted like I was gagging and throwing up over the side of the boat for the benefit of the next guy. It was a short ceremony—forty-five minutes or so—but everybody got a good laugh. It relieved some of the tension.

After we crossed the equator, I was getting six or eight pings a day, and none of them were whales. Everybody was waiting for the captain’s order to fire on the Japanese ships. We had twelve torpedoes—six loaded in the tubes and six more in reserve—but he kept saying that the targets were out of range, too far away. Either that, or they were at the wrong angle. I have no doubt that was true. The Dolphin wasn’t fast enough to catch a maru from behind, let alone a warship, and our torpedoes had no guidance system. They were like firing bullets from an underwater rifle. The captain was probably saving his ammunition for the best possible shot, which would be the broad side of a ship crossing in front of us. It reminded me of hunting deer: You have to hide in the meadow and wait for that big buck to walk right past you. Range and angle was everything.

The XO agreed with the captain’s decision to hold his fire—until a big Japanese cruiser came into view. It was well within range of our torpedoes. The only problem was, that cruiser was coming straight toward us. We would have had to aim for the bow, which was a very narrow target. The XO called this a “down-the-throat”

shot, and he was desperate to try it.6 The COB said it was a waste of a torpedo. More than that, he was worried about revealing our position to the cruiser. He was so certain we would miss it, and then they would fire back at us. He advised the captain to let the cruiser go because the Dolphin was too slow and too crippled to get away. They had a three-way shouting match around the periscope, until finally the captain couldn’t take it any more. The Japanese cruiser was passing out of range when he left the command center. Everyone said he had what they called a nervous breakdown. I never saw the captain again. He stayed in his private quarters for the rest of the mission.

The XO took charge of the Dolphin, and all of the other officers accepted him as their unofficial captain. So did the COB, and the rest of the enlisted men followed him. But the XO did not order us to fire on the next Japanese ship that came within range of our torpedoes. At that point, we were too close to the enemy bases in the Marshall Islands. Our orders were to spy on them, and that’s exactly what we did. For the next week and a half, we just sneaked around from one island to another and counted the number and type of ships at each base. Sometimes we were less than two hundred yards offshore. I got to look through the periscope myself. I saw two or three cruisers and several destroyers coming and going, but most of the ships in the Marshall Islands were marus. If I’d known how to read Japanese, I could have reported what was in the boxes and crates they were unloading. We were close enough to read the labels. Every time a ship left the dock and came toward us, we lowered the periscope and prayed they didn’t see it. The XO quit putting on the headphones when I told him I had a ping. He was ordering crash dives on my say-so.

I don’t know how we managed to stay undetected for as long as we did, especially when we started snooping around Kwajalein. 7 That was the biggest and busiest harbor we could find in the Marshall Islands, and that’s where I got the loudest pinging I’d ever heard on sonar. It was a Japanese destroyer. We crash-dived and hoped it was on its way out to sea. But the darn thing just sat there on the surface above us. I was probably more scared

than anybody because I’d been on a destroyer myself. I used to think it was fun to watch the depth charges explode. Now, they were just the deadliest weapon I could imagine. The XO didn’t look scared, but I think he was. He took us deeper than we’d ever been before. I’m sure we were well below two hundred feet that day, because I never saw so many leaks all at once. We had to shut down every system and act dead in the water. If the enemy destroyer’s sonar was anywhere near as sensitive as ours, they could have heard our propeller. Nobody talked above a whisper; we didn’t dare shake the dice for acey-deucey. We even took off our shoes when we walked from one end of the boat to the other. You could smell the fear. I was almost afraid to breathe. I thought I was going to die that day.

The pinging stayed loud for hours and hours, until it finally faded and stopped. I have never known whether that Japanese destroyer was really looking for us or not. If they dropped any depth charges, I did not feel the concussion. They must have exploded more than thirty yards away. When the XO finally brought us closer to the surface, we had so many serious leaks from one end of the boat to the other, he called off the mission. I guess he finally agreed with the COB, and so did I. We probably could not have survived another crash dive. I wasn’t even sure we were going to make it out of the Marshall Islands, let alone all the way back to Pearl Harbor.

We stayed submerged until we were out of enemy territory, and then we started transmitting our reports back to headquarters. That was an adventure, too, because our radio antenna was still shorting out. We didn’t know if any of our information was getting through.8 For incoming messages, we relied on the Fox Schedule. That was a system where each transmission from CinCPac was numbered and broadcast over and over again. If you didn’t get it the first time, you might pick it up the next day, or the day after that. You have no idea how relieved I was when I copied the message that said the Dolphin had permission to return to base. We were about halfway back to Hawaii when we got that one.

We did not see any enemy ships after we crossed the equator on the way back to Pearl Harbor, but we did see some of our own. One was the carrier Enterprise. There were several cruisers and destroyers around it, and the whole task force was headed south. I knew better than to ask where they were going. The movements of the carriers were always highly classified.9 What I mainly remember about returning from that mission is the crew’s low morale. Everyone on the Dolphin felt like a failure. We didn’t sink a single enemy ship. We didn’t even fire any of our torpedoes. All we had to show for over a month at sea was something like thirty-five “deficiencies.” I saw the XO’s checklist. I also saw that he’d marked over half of those mechanical problems as “serious.” I have no idea if the Dolphin was ever repaired enough to go out again, and I never heard what happened to the captain. He was still holed up in his quarters when we pulled up to the docks.10

I was grateful to come back from that mission alive. I can’t remember a time when it felt so good to walk on solid ground. As soon as I got to the barracks, I went looking for Scoop and Spic, but I couldn’t find them anywhere. Their bunks were empty, and their seabags were gone. All of the radiomen at headquarters were new. I’d only been gone for a month or so, but nothing at the submarine base was the same. Even Lt. Commander Guenther was gone, and there was a new admiral in charge of the Pacific Fleet.11 It felt so strange, I requested sea duty again. I thought they’d put me on another submarine, and that was okay with me, as long as it wasn’t the Dolphin. I couldn’t believe it when I saw my orders. I’d never even been close to an aircraft carrier before. I thought I was lucky to get the Yorktown.