THE SUMMER OF ’42

June 10–September 1942

We had no orders, and there was no one waiting to meet us at the dock. I could have caught a ride to Honolulu and just melted into the city until the war was over. The thought did cross my mind. I don’t know where the other survivors went: Everybody took off in different directions. I walked over to the submarine base alone. I had no reason to believe that I belonged there, but that was the last place I’d been before I boarded the Yorktown. I couldn’t think of anywhere else to go.

The administration building looked about the same—I noticed they had a few more machine guns on the roof—but there was not one familiar face inside. The radio gang at CinCPac headquarters must have had another complete turnover since February. Even the communications officer was new again, and I had no papers to prove I was me. I just told him what happened, and I guess he believed me, because he let me stay. He took me in like a stray pup.

The sub base barracks were a lot more crowded than I remembered. 1 I got the last empty bunk on the second floor. I wandered

around, looking for Scoop and Spic. Nobody had ever heard of either of them. It was like my best friends in the Navy never existed. I had a real hard time with that. Everybody probably thought I was a little crazy because I kept asking, “Are you sure?” But I think I was even lonelier for my shipmates from the Yorktown. When you’ve been at sea for as along as I was, the ship is your home and the guys you work with are your family. I had one required counseling session with the sub base chaplain, right after my postcombat physical, also required. I wouldn’t be surprised if a lot of Yorktown survivors had to have major psychiatric treatment. In my case, the chaplain said I just needed time. He cleared me for duty at CinCPac headquarters in less than a week.

I was still lonely and a little depressed, but I did go to the party that Admiral Nimitz had promised. Boy, did he ever follow through. Toward the end of June, the Navy sent buses to pick up all the Yorktown survivors at Pearl Harbor. They took us to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu and wined and dined us all night. We even had an open bar, with all the fancy tropical drinks and cocktails you could imagine—anything you wanted, with or without alcohol—and it was all free. Two or three different bands took turns playing for us, and then here came the girls in the grass skirts, and we took turns with them, dancing in the sand. I was kind of looking forward to the fights. What else would you expect from a few hundred sailors, and all that free booze, and maybe one girl for every ten guys? But would you believe it, nobody threw a single punch. Not that night. It seemed like everybody just had this real mellow attitude toward the whole human race. We knew we’d beaten the Imperial Japanese Navy at Midway, and we thought that was the end of the war in the Pacific.2 I never saw so many guys hugging each other. I actually saw sailors hugging Marines. I thought that was going a little too far, myself.

I stayed out pretty late that night—okay, I partied ’til dawn—but I swear it wasn’t for the free mai tais, or the hula girls. I didn’t want to leave because I knew this was probably the last

time I would ever see most of those guys. Oh, there was lots of scuttlebutt to the contrary. Everyone was talking about the Navy’s new aircraft carrier. We heard they were going to name it after our Yorktown, and wouldn’t it be great if we could be her first crew.3 I would have liked that. I just didn’t think it was very realistic. Some of the radiomen and gunners I talked to that night already had orders to other ships in the fleet, and I was sure Japan would surrender long before the new carrier was ready to go to sea. If not, it wouldn’t matter to me, because I only signed up for four years in the Navy. My biggest concern at that time was, how much more education can I possibly get out of the Navy before I’m out on the street in a few months, looking for a job in the civilian world.

The radio gang at the submarine base advised me to try for Radio Materiel School in Washington, D.C. That was the most advanced training a Navy radioman could get. You didn’t just learn how to repair radio equipment, they taught you how to build a whole radio station from the ground up. All I had to do was get past the entrance exam, which was pretty funny, because you had to know a whole lot of geometry and trig, and I didn’t. Basic algebra, yes. I took that before I dropped out of high school after tenth grade. But there was this one chief radioman at the sub base: He’d just come out Radio Materiel School himself. He had all the books. He even promised to help me study for the exam. I had a thirty-day leave coming—that was Admiral Nimitz’s other promise to everybody on the Yorktown—but I was afraid to take it. As fast as the Navy moved guys around, I knew that chief radioman might not be there when I got back. And I wasn’t all that sure where I stood with my girlfriend at that time.

I didn’t get a single letter from Adeline while I was on the Yorktown, and there were none waiting for me when I got back to Pearl Harbor after Midway. I didn’t know she’d been writing to me all along. The letters just piled up at the Fleet Post Office in San Diego for months and months. When the Navy finally got around to telling the FPO where I was, I got about twenty letters all in one day. She wrote numbers on the envelopes, so I knew in

what order I was supposed to read them. That was scary. Every time I opened the next letter in the sequence, I thought, okay, this must be the one that says she’s tired of waiting for me. But she never said that. From first to last, every letter said she still loved me. I wanted to write back and explain why she hadn’t heard from me for such a long time, but I knew better. The censors would have cut out anything about what happened on the Yorktown. Shoot, I couldn’t even say what happened to my wallet. I just told her it got wet, and could she please send more pictures.

There was another big stack of letters from my mother. She didn’t number hers, so it was a little harder to follow all the news from home. My two older brothers were joining the Army, which was no surprise. Mom said practically all the guys in my hometown were either drafted or volunteered for some branch of the military right after the attack on Pearl Harbor.4 What shocked me was the women, especially my mother. She had always been a prayer warrior. That’s what we called the folks that prayed for everybody in the military, right on up to the Commander in Chief of the whole country, which was President Roosevelt. Now she tells me it’s also her patriotic duty to get on the bus to Little Rock every day, along with all the other ladies in the church. Most of those women had never worked outside their homes in their entire lives, and now they’d all got jobs in a factory. I couldn’t believe it when my mother told me she was making airplane parts for the military.5

I was still going through my mail when a Yorktown survivor dropped by the barracks. He was a yeoman, one of the guys that helped salvage the ship’s files before it went down at Midway. He brought me my liberty card from the Yorktown, and we both had a good laugh about that. I never had a liberty while I was on the carrier, so this was the first time I’d ever seen the thing. If I had, I would have told them to fix the mistakes. The most obvious was my rating: I was not an RM3c on that ship; I was an RM2c. I’d been wearing two stripes and drawing the higher pay of a second class radioman and petty officer for almost a year before I boarded the Yorktown. The second error was my date of

birth. I guess the Navy hadn’t got around to correcting the lie I told on my application. They still had me a year older than I really was. But I knew my mother would like the picture, so I signed the card and put it in the mail. I told her to keep it as a souvenir from her son in the U.S. Navy. That’s about all a canceled liberty card is good for.

I could have been assigned to another submarine crew. I didn’t ask for that, and, quite frankly, I hoped I wouldn’t get those orders. I think there were at least two submarines that never came back that summer.6 The sub crews that did survive their missions were generally disgusted and discouraged. According to them, about every other torpedo they fired was a dud. Some said it was because the explosive chemicals were old; others claimed there was something wrong with the firing mechanism.7 The worst story I heard was from a guy who’d been on a mission with the Perch. He said they fired twelve torpedoes and never got a single kill.8 I don’t know if all the submarines had such bad luck. I didn’t get to talk to those guys as much as I did before the war, because they weren’t around the pool much anymore. The Navy was putting them up at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel instead. I thought that was great. As far as I was concerned, submariners deserved every bit of pampering they got between missions. I just wish the Navy had done that a little sooner. I would have loved to spend a week or so at the Royal Hawaiian after that hellish mission on the Dolphin.9

I did see a lot of Admiral Nimitz that summer. He had to walk past the radio shack to get to his office in the administration building. Sometimes he poked his head in and spoke to our communications officer. The civilian press reporters were always asking for interviews. He didn’t grant very many while I was there. He didn’t much care for the photographers either. When Admiral Nimitz did consent to a picture, more often than not he wanted it taken with a few enlisted men. I think all of us who worked at CinCPac headquarters got called for that kind of duty at least once. But the main thing I remember about him is the two times he spoke to me, and both times he called me “son.”

My first conversation with Admiral Nimitz was in his office. I’m not sure why he was moving his desk and generally sprucing up the place. It may have had something to do with the rumors. We heard President Roosevelt was planning a visit to Pearl Harbor, maybe even that summer.10 Whatever the reason, Admiral Nimitz wanted his desk in the center of his office, and the cord on his telephone was too short to reach it. It was a very simple job. The only reason it took me more than a few minutes was that I wanted to wrap the extra cord around the leg of the desk. I was afraid he or the President might trip over it if I didn’t. I was still on my knees behind the desk when the admiral returned with his coffee. He watched me finish up, and then he said, “Son, that’s a mighty fine piece of work.” He thanked me several times while I gathered up my tools, and he was still thanking me when I left. I was so embarrassed. All I did was install a longer cord on his telephone. The way he carried on, you’d have thought I won the war.

The second time Admiral Nimitz spoke to me, I thought he was going to throw me in the brig for assaulting an officer. I didn’t mean to scare him, and I wasn’t trying to knock him on his keister. It was an accident. I was just running errands around the submarine base, and for some stupid reason, I decided to take a short cut by jumping off the torpedo loading dock. It was about a six-foot drop. I really should have looked to see if there was anyone on the sidewalk below. I landed on my haunches, right in the middle of three admirals. Two of them came up cursing. I didn’t know who they were. The only one I recognized was Admiral Nimitz. I thought I was dead meat, and I probably would have been if not for him. He just chuckled and said, “That’s all right, son. Were you in a hurry to get to the mess hall before they close for lunch?” I said, “Yes, Sir. I’m sorry, Sir.”

Everyone at CinCPac headquarters thought Admiral Nimitz was a genius. I don’t know of anyone at Pearl Harbor who didn’t admire the way he was running the war in the Pacific.11 But, in my experience, he was also the kindest man in the world, and he had the bluest eyes you ever saw. I will never forget how they sparkled in the sun that day. He winked at me and told me to keep running.

Everyone at the submarine base was good to me that summer. I could have made a lot of close friends there, but I didn’t want to. It seemed like every guy I ever really cared about in the Navy either disappeared or got killed during the first six months of the war. I didn’t want to go through that kind of grief again. The radiomen at headquarters did invite me to the beach with them once or twice. All I remember is the rolls and rolls of barbed wire all along the shore. I guess the Army and the Navy in Hawaii was still thinking Japanese troops might try to land on Waikiki.

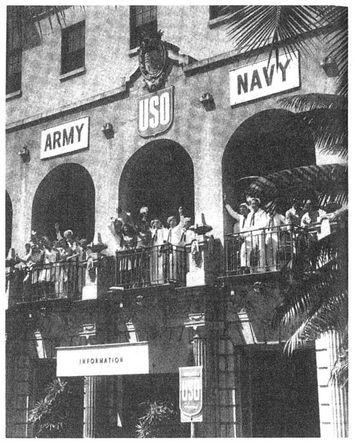

The nights in Honolulu were pretty strange, too. The whole city was blacked out. The military and civilian police could write tickets and fine anybody who showed a light from their houses or businesses after dark, so a lot of the stores locked their doors at sunset. Of course, the bars and the taverns never closed. They just boarded up the windows and lit candles. That didn’t bother the sailors any. Some thought it actually enhanced the nightlife. Candlelight is more romantic, I guess. The USO clubs were always open, too. That was really the best and cheapest entertainment there was for guys in the military.12 Whenever I went to the USO in Honolulu, I tipped my cap back like everybody else. Two fingers above the eyebrows was regulation; beyond that it was a signal that you were single and available. But I hardly ever asked the USO girls to dance. Where I came from, most churches considered dancing a sin, so I never learned how. I just listened to the bands. There weren’t enough girls to go around anyway.

The USO center in Honolulu served up to 250 gallons of ice cream per day to American military personnel. This and 75 other USO centers and mobile units in the Hawaiian Islands provided entertainment and services to 2.25 million troops in one month during World War II. COURTESY OF THE USO.

I took the entrance exam for Radio Materiel School in August. Glory be, and thanks to the chief radioman’s tutoring, I passed it. All I had to do was get the communications officer to put through my application, which turned out to be an even bigger challenge. Every other day, I asked him if he’d done the paperwork yet. He was a patient man, but he finally blew his stack: “Sailor, don’t you know we’re in the middle of a war here?” Well, no, I didn’t know that. I thought we were at the end. I mean, good grief, we sank four Japanese aircraft carriers in one day at Midway. I didn’t think they had anything left to fight us with. I was not aware that Japan also had a powerful Army.13 I didn’t know there were Japanese troops on islands all over the Pacific, and I most certainly did not understand how hard they intended to fight to keep them. None of that was really clear to me until I saw the lists of casualties from Guadalcanal and other islands in the Solomons.14 The Marines were obviously in heavy combat on the ground, and I was so sorry for all the times I called them seagoing bellhops on the Yorktown. It was only after I saw the reports from Guadalcanal that I understood what the Marines really were. Those guys were warriors. Incredibly brave warriors.

I don’t recall what was going on with the war in Europe that summer. We didn’t get much news from there at Pearl Harbor. All I remember is the long lists of Merchant Marine ships that

were reported sunk by German submarines in the Atlantic. The lists were shorter in August than they were in June.15 According to the scuttlebutt at CinCPac headquarters, this was due to all the new destroyers the Navy was getting. I heard a lot of them went right to convoy duty. They were protecting the troop and supply ships that were going to England.

Toward the end of the summer, it was beginning to dawn on me that the war might last another year or two, and, yes, I did feel a little bit guilty for wanting more education instead of another tour of duty on a warship. But not that guilty. The minute I found out I was accepted into Radio Materiel School in Washington, D.C., I put in my request for a thirty-day leave and shot off a letter to Adeline. I told her I was on my way back to the States.