COLD BAY

July Through December 1943

I saw snow on the mountains in the distance, but the sun was shining as we approached the Aleutian Peninsula. Temperature was about sixty degrees. I didn’t think that was bad at all, until the ship’s crew informed me that this was what you called a scorcher at Cold Bay in July. We had to wait outside the harbor entrance for the Coast Guard cutters to lift the sub net.1 It worked sort of like an automatic garage door, except that it was underwater. Pearl Harbor had a sub net, too, for keeping enemy submarines out and away from the warships, but there were no warships inside the harbor at Cold Bay. There wasn’t even a base. All I saw was a few small fishing boats and a tiny little village.

The name of the village was King Cove, and the fishermen were obviously civilians. I was warned not to call them Eskimos. The lumber ship crew referred to them as “Aleuts.” I don’t know what they called themselves.2 What really got my attention was their dock. I’d never seen such a dock—military or civilian—anywhere in the world. It was over eight hundred feet long and

wide enough for trucks, but there was only one jeep on it that day, and the driver was waving and calling to me. I had a lot of questions for that guy.

We drove inland for about fifteen miles, which seemed a little odd for a naval air station. They were usually closer to the water. I thought I would see forests along the way, but there was not a single tree in sight. Not even a bush. It was just grass and moss, as far as the eye could see, all the way to the mountains, and the ground looked kind of wavy, like there was water sloshing below the surface. The jeep driver called it “tundra.” He said it felt kind of squishy when you walked on it. The only animals he’d ever seen on his trips between the harbor and the base were seabirds and caribou.3

There were tanks on the hill above the base. As we got closer to the runway, I saw planes with Army Air Force markings. The jeep driver said they came from Fort Randall, the Army base a few miles farther down the road. He didn’t know why the Army was parking tanks and bombers at a naval air station, but he was able to explain all the strange-looking buildings. “Quonset huts,” he called them.4 They came in all different sizes; the smaller ones were buried in the ground, almost up to the roof. I thought this was probably for extra insulation from the cold, but the driver said, “No, it’s to keep the darn things from blowing over in the wind.” And then he stopped at the hut with a sign over the door. The sign said PARADISE LOST.

Paradise Lost was one of the dozens of Quonset huts that were used for barracks at Cold Bay. It had an oil-burning stove and bunks for about fifteen enlisted men. Half of my bunkmates were radiomen; the rest were torpedomen. I had a lot of questions for them, too. By the time I unpacked my seabag, I thought I knew the score. They told me about the thousands of Japanese troops on the islands west of us. About a month ago, they said, there was a terrible battle with them on the island of Attu. It sounded like a bloodbath. I heard our guys ended up killing every last enemy soldier on that island, because the Japanese Army didn’t believe in the concept of surrender. They didn’t care if

they were outnumbered or outgunned. They would rather die in combat than be taken as prisoners of war.5

According to the radiomen who bunked at Paradise Lost, there was going to be another big battle with the Japanese troops on the island of Kiska. They thought it would be even worse than Attu, because there were even more enemy soldiers on that island. They also believed that Japan would invade us at Cold Bay eventually. Well, that sure explained why the Army had tanks on the hills around us. The torpedomen said that the Navy had all kinds of warships to defend us, too. Whenever they needed more ammunition or supplies, the torpedomen had to haul it across the tundra to that huge dock in the harbor. They hated that job, but I guess that was the Navy’s deal with the Aleuts. The villagers were kind enough to put up with the dock, the sub net, and all the warships that came and went in their fishing waters. They just drew the line at the Navy’s request for an air base next to their homes on shore. I could understand that.

The Aleuts at Cold Bay were clearly on our side. Maybe they were as afraid of the Japanese Army and Navy as we were.6 But I think the main reason we got so much cooperation from the local civilians was our base commander. He was an Aleut. The way I heard it, he used to be a fishing boat captain, until the Navy gave him the rank of commander and put him in charge of this base on the Aleutian peninsula.

For me, being at Cold Bay in the summer of 1943 felt like I was right back at Pearl Harbor in those first few days after the attack in December 1941. There weren’t any palm trees or tourist hotels on the beaches, but the paranoia—the fear of invasion by Japanese soldiers on the ground—was exactly the same. And the radiomen were laughing at me. All I said was “Where’s the radio shack?” They were still laughing when they took me outside and pointed to a big, fresh-dug hole in the ground. The joke was, the Navy did not have a radio station on the base at Cold Bay. We had to build it ourselves, from scratch, in a hurry.

Setting up the Quonset hut was easy: The pieces snapped together like a tinker toy. We had that thing in the hole with the

roof on in a couple of hours. The wiring was something else. It takes a lot of electricity to power a full-blown military radio station. For about a week, we worked day and night. Well, actually, there was no night at Cold Bay. When you’re that close to the Arctic Circle, it doesn’t get dark in the summer. I couldn’t sleep at all for the first couple of days. I finally got so tired, I didn’t care if the sun was up, down, or sideways. There were some advantages to working under the “midnight sun”: You could read a technical manual outside at midnight. We didn’t even need flashlights when we sneaked around the base and stole tools and equipment from the Army at two in the morning.7 The Navy had a special term for this. It wasn’t stealing. It was a “midnight requisition from small stores.”

The only really big thing we filched from the Army was a generator. It took four of us to haul that monster down into the hole. We almost had it through the door when it slipped off the dolly and pinned me against the wall. I woke up in sick bay; the corpsman was standing over me with a bedpan. He said I had three crushed vertebrae, and it might be awhile before I could walk again. When the radiomen came by to see how I was doing, they said I probably did it on purpose, to get out of all the wiring we still had to do. Yeah, right. My back was in traction, I’m sipping dinner through a straw, and all the doctors and nurses had beards. There were no women anywhere on the base at Cold Bay.

The one good thing about being laid up was that it gave me time to study for the GED test. I promised to write and tell my high school principal when I passed it, which I did. A month or so later, here comes this little package in the mail from Vilonia High School. It was my class ring. The note from Mr. Bollen said it was a gift from the class of ’38. I knew better. I’m sure he bought and paid for that ring himself. The stone was a red ruby. I don’t know how much it cost—probably thirty or forty dollars. That was a lot of money for anybody in 1943.

By the time I got out of the base hospital, the new radio shack was up and running, and we were swamped. Some of the messages came from CinCPac at Pearl Harbor, but it was mostly requests

for more torpedoes and supplies from our warehouses. I think every Navy warship in the Aleutians stopped at Cold Bay at least once that summer. We were also functioning as air traffic controllers for all the Army Air Force pilots who were flying in and out of Fort Randall that summer. Whenever their runways were overcrowded or fogged in, they requested clearance to land on the Navy’s runways at Cold Bay.8 On top of that, we were getting all kinds of enemy sightings from the Aleuts. Their fishing boats had radios; some even had sonar. Whenever the Aleut fishermen spotted a Japanese ship or submarine, they called in the location to us. We relayed that information to any Army plane or Navy ship that was close enough to go out and chase it down. The Aleuts were really valuable allies in those waters, but we had to be extra careful whenever we communicated with them on the radio. Very few of the local fishermen were as fluent in English as our base commander.

Radioman (RM1c) Ray Daves, 23, at door to stairs leading to below-ground radio shack (“Navy Radio Communications Duty Office”), Naval Auxiliary Air Field (NAAF) Cold Bay, 1943. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Radioman Ray Daves at work inside the radio shack, NAAF Cold Bay, 1943. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Toward the end of July, I thought the Aleuts were imagining all the Japanese submarine sightings they were calling in. There were so many, I wondered if they were seeing whales. I’d made that mistake on sonar myself, lots of times. But then I started picking up Japanese transmissions on my own headphones, sometimes two or three times a day. It happened so often, I got so I could recognize their fists. The Japanese radiomen’s key taps were every bit as distinctive and individual as ours. One particular Japanese radioman broke into our frequencies so often, I was pretty sure he was doing it on purpose, to disrupt our transmissions. That was only a nuisance: It made me stop and start over from the beginning. It was just scary to think how close he must have been to break in to our military frequencies. And unless Japan’s radio technology was a whole lot better than ours, it meant those submarines were on the surface, too.

There were never enough planes or ships in the area to chase down all the submarine sightings we were getting at Cold Bay that summer, so the base commander ordered us to start flying

search-and-destroy missions ourselves. None of the radiomen had taken the course for aviation gunners, but there was no time for training. We just put on our Mae Wests, climbed in the backseat behind the pilot, and hoped for the best.

Radioman Ray Daves in flight gear, including Mae West life vest and leather helmet, prepares for aerial search and destroy mission. NAAF Cold Bay, 1943. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

The only Navy planes we had on the base at that time were OS2U Kingfishers. It wasn’t much of a sub killer. The Kingfisher was nothing more than a scout plane—the same kind they catapulted off the cruisers, the kind I swore I would never fly in again. But that was before the war. I was pretty relieved when I saw our Kingfishers had wheels instead of pontoons. They could take off and land on a normal runway, like a normal plane. They also had bomb racks—one underneath each wing—but the bombs were only a hundred pounds each. I don’t know what made us think we could do any damage to an enemy ship or submarine with such a small bomb load. The only other armament on that plane was the radioman’s thirty-caliber machine gun, unless you count the two Colt .45 pistols. I carried one in a holster on my right hip; the pilot had the other. I’m sure the Japanese sub crews were real scared of those, too.9

We flew in pairs, but we didn’t always stay together for the

whole mission. Whenever I looked over and saw my wingman, I got a real warm-fuzzy feeling. It was actually kind of fun to fly search-and-destroy missions out of Cold Bay, but the truth is, it’s a wonder any of us ever lived to tell about it. I think we were just lucky. The Japanese submarines were always submerged by the time we got to the Aleuts’ coordinates. We never found any enemy ships on the surface either. They must have been out of our fuel range or hidden in the fog. If we’d ever tried to bomb a Japanese ship or sub on the surface, their antiaircraft guns would have shot us down like a dead duck. Other than that, I suppose the greatest danger was the weather, unless it was your turn to fly with Fish.

Of all the Navy pilots at Cold Bay, Fish was the daredevil. We called him Fish because he flew so low over the ocean that the propeller splashed icy cold water all over the radioman in the backseat. The only reason anybody put up with being his gunner was that he was a darn good pilot, most of the time. Fish liked to fly low over the ground, too. When we saw caribou on the way back to base—and if he had enough fuel to fool around with—he would tell me to take target practice. You don’t have to be a very good shot to bring down a caribou with a thirty-caliber machine gun. I could usually pick off three or four in a single pass over the herd. And then I would get on the radio and tell the cooks where to find them. The meat was a little tough and stringy, but we were glad to get it. Anything was better than Spam.

Fish had this one real nasty habit when the fog rolled in. If we couldn’t see the runway in the fog, he would order me to give him a fix on the homing beacon. He would just dive—nose down, full speed, and blind—and he would not pull up until the very last second before we hit the ground. And then he’d turn around and ask you if you’d wet your pants. Twice he did that to me. I decided he was crazy. I flat refused to fly with him again. It wasn’t very long before all the other radiomen did the same. I have no idea whatever happened to Fish. The base commander had him transferred out of Cold Bay. They could have used him on an aircraft carrier. He would have made a great dive-bomber.

I especially remember coming back from one of those search-and-destroy

missions in the month of August. I was still in the hangar, putting away my flight gear, when I heard another plane approaching our runway. I knew by the sound of the engine that this was no Kingfisher, so I went out to see what it was. I didn’t always recognize the Army Air Force plane types, but I knew this was a P-38 Lightning as soon as I saw the two tails. The pilot made a perfect landing. I thought I was dreaming when he climbed out of the cockpit and hollered my name. It was Gale Stevens. There were only thirteen in my class at Vilonia High School, and he was one of them. We’d known each other since first grade. I heard he’d joined the Army right after graduation. Cold Bay was the last place in the world I ever expected to see him again.

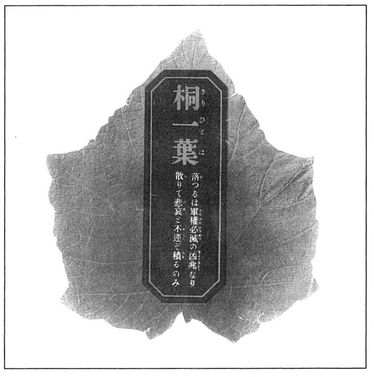

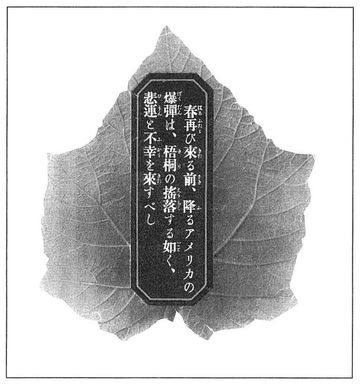

Gale and I didn’t have a lot of time to visit: There was a jeep coming for him from Fort Randall. I know he sure thought a lot of his P-38. He told me he flew it in combat against the Japanese on Attu. He said that was where he learned to fly low and strafe the enemy soldiers on the ground. I did not ask him how many he thought he killed that way or how many Zeroes he shot down over Attu. I assumed he hated those kinds of questions as much as I did, and we were both pretty sick of the war in general. We just talked about old times, and wouldn’t it be great if we could both go back to Arkansas and be kids again. I wished him luck at Kiska. Everybody knew there was going to be a real showdown with the Japanese troops on Kiska Island any day.10 I’m sure the enemy knew it, too, because I saw the leaflets our bombers were dropping on them. One pilot left a whole bundle of those leaflets in the radio shack at Cold Bay. We didn’t know what it said: All the words were in Japanese. I took one for a souvenir.11

Gale never landed his P-38 on our runway again, but a lot of other guys from his squadron did. They told me my friend’s plane was not shot down over Kiska. Nobody was. According to them, the island was totally deserted when our troops landed on the beaches. We didn’t know how the Japanese managed to get that many thousands of soldiers off that island without detection, but I guess they did. Maybe those leaflets did the trick.12

It was a little later in August when another pilot stopped by the

radio shack and showed me a Japanese officer’s diary. He said he found it beside the man’s body after the battle on Attu. It was in Japanese handwriting, of course, but somebody had already translated the whole thing into English, and I typed a copy of that. He must have been a doctor, because I remember the part where he said he used grenades to kill all of his patients. I assumed he did it to prevent them from being captured alive. I don’t know if he committed suicide afterward or if he was killed in combat the next day. All he said was that it was an honor and a privilege to die in service to the Emperor. The pilot who found his diary told me he was sending the translated copy to the War Department in Washington, D.C. The original, he said he was going to keep until the war was over. He swore he was going to take that diary back to Japan and turn it over to the man’s family. I don’t know if he ever found them. I’d bet a month’s pay that he tried.

“Kiri leaflet” dropped on Japanese-occupied Attu and Kiska translates as follows: “This sign tells you the military of Japan is powerless now and only gives you tragedy and misfortune.” Translated by Michiko Takaoka, Director of Japanese Cultural Center, Mukogawa Fort Wright Institute. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Reverse side of “kiri leaflet” reads: “In next spring, the pouring American bombs will give you tragedy and unhappiness like falling down paulownia leaves.” Translated by Michiko Takaoka. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

The Aleuts’ sightings tapered off quite a bit in September. There was very little we could do about them anyway: The fog got thicker and lasted longer in the fall. I doubt if even Fish would have been crazy enough to take off in a williwaw. That was the local word for this peculiar kind of windstorm. It was even worse than the blizzards in the mountains of northern Idaho when I was in the CCC. The williwaws in the Aleutians came swirling in from all directions at once, sometimes with rain, sometimes with snow, always with fog.13 You couldn’t see more than a few feet ahead of you, in the air or on the ground. The thermometer was irrelevant. We didn’t measure windchill. It felt like fifty below when the Navy started issuing these real heavy parkas with no buttons or zippers down the front. You just pulled it over your head like an oversized sweatshirt. On me, it was more like a dress.

From about October on, nobody wanted to go outside. I never missed a meal myself, but there were some who did. They

said they would rather starve than walk the hundred yards to the mess hall in a williwaw. The snow got even deeper in December, and, of course, that whole midnight sun thing reversed itself in the winter. It was dark all the time. We couldn’t fly, and there were hardly any ships coming into the harbor. Nobody had anything to do, and it began to feel like the whole object of being at Cold Bay was to keep warm and stay sane. Some didn’t. I remember one yeoman who developed a weird fixation on his hair. He couldn’t seem to quit combing it. For hours on end, he would part it this way and that way and then back again. He finally got so bad he just stood there and stared at himself in the mirror all day. The base commander had him transferred to a psychiatric hospital on the mainland.

The base recreation officer did the best he could. He got the Navy to bring us some treadmills and weight-room equipment. We even had a hot tub of sorts—it was more like a whirlpool bath—and the corpsmen gave great massages. At night, we had movies in the mess hall. We had to show the same ones over and over until the fog cleared enough for the cargo planes to bring in a fresh batch. I ran the projector—the cooks brought me an extra piece of cake or pie for that—and every movie came with a newsreel. They were usually a week or two out of date by the time we got them, so it was hard to keep up with the war. I was glad when I heard the Italians switched sides and joined the Allies. The bad news was how many of our bombers—they called them Flying Fortresses—were lost over Europe. I could hardly believe the Germans shot down sixty in a single day.14 The newsreels from the Pacific were even worse. The Marines were taking heavy casualties again, only this time it was on Tarawa, in the Gilbert Islands. I never saw the casualty lists from that battle. Based on the newsreel footage, I assumed the numbers were as bad or worse than Guadalcanal.15

There wasn’t quite as much concern about Japanese troops coming ashore at Cold Bay after winter set in, but no one knew if they had really given up on the idea of invading Alaska altogether. Every few days, when the air raid sirens went off, we had to grab our rifles and run to battle stations until we got the all

clear. It was always a false alarm. But I never heard much “woe is me.” I think everybody just accepted where we were, and we all knew it could have been worse. The weather was miserable, but we weren’t dodging any bombs or bullets on the beaches.16

Recreation officer Ensign Bell, left, and radioman. Ray Daves, outside the Navy’s post office at NAAF Cold Bay, 1943. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

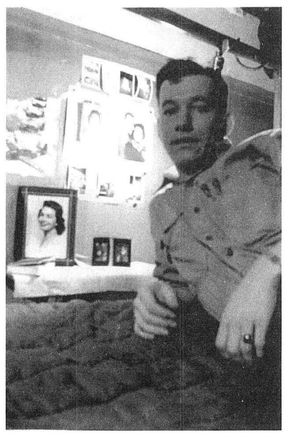

I don’t know how the other barracks passed the time between shifts. I suppose they played cards, the same as we did in Paradise Lost. When I got tired of that, I read books and magazines from the base library. Everyone looked forward to the days when the fog lifted enough for the planes to land with all those sacks of mail from home. It was a special treat to get a letter from your girlfriend with a “kiss” inside. Girls blotted their lipstick on a tissue and put that in the envelope with the letter. I got lots of those from Adeline. Whenever she sent me a picture, I pasted it on the wall next to my bunk. I taped black paper over half of the lightbulb so the other half shone on her, like a spotlight. And I remember how my arms ached—it was a real, physical aching

sensation—when I stared at those pictures. I wanted to hold her again.

Radiomen and torpedomen return with rifles to Paradise Lost barracks after an air raid alarm. NAAF Cold Bay, 1943. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Studying helped. I knew it was probably a waste of time to take the next promotional exam, because I was a first class petty officer. After that, you’re a chief petty officer. Everybody knew it didn’t matter how high you scored on the chief petty officer exam. You couldn’t “make chief” unless there was an opening in your specialty. Besides that, I was only twenty-three, and all the chief petty officers I’d ever known were guys in their forties and fifties. They were like a bridge between the officers and the enlisted men in the Navy. Whenever the officers wanted to know what the enlisted men in any section were thinking or worried about, they depended on the chiefs to give it to them straight. Which is why I had no business taking the chief petty officer exam in December at Cold Bay, but—hey—what else was there to do.

The other radiomen were as bored as I was, so we put together a civilian-type radio show and started broadcasting our own programs. This was totally illegal. You were supposed to get FCC approval

for a new radio frequency in U.S. territory. We never even applied for it. The base commander’s permission was good enough for us. I think that’s one of the reasons everyone at Cold Bay liked him so much. He wasn’t afraid to break the rules. He even signed our supply requests for all the newest records from the big bands. When the Navy sent those, we started taking song requests like disc jockeys. If it had been up to me, we would have played more classical music—I was really getting into it after that concert in Seattle—but most of the guys in the barracks wanted top forty. The only request I dreaded was “Red Sails in the Sunset.” That was Adeline’s favorite; she called it “our song.” I always got depressed when somebody asked for that one.

The torpedomen had absolutely nothing to do. There were so few ships coming in for ammunition or supplies that winter. The only torpedoman who didn’t seem to mind having all that time on his hands was Hector Lebree. Hector was perfectly satisfied as long as he had his sketchbook and pencil. I thought he was a great artist; everything he drew was signed “by Hec.” His dream was to be a cartoonist for the Disney studios, if he survived the war. All the other torpedomen were making trips to the warehouse. They claimed it was part of their job to check on the torpedoes. Everybody knew they were just drinking the fuel. We called it “torpedo juice.” I have no idea what it tasted like—I never touched the stuff—but I know it had a very high alcohol content. The torpedomen were getting snockered on it. We told them it was dangerous. The Navy was sending all kinds of warnings about torpedo fuel. The memos said it could cause blindness, if it didn’t kill you first. Well, the torpedomen in Paradise Lost drank it anyway. One guy got so drunk, he grabbed his rifle and ran outside in his underwear. I guess he got it in his head that we should have an armed guard at the door. He just kept saying, “I are at war!” We wrapped some pants around him before we took his picture. Then his buddies dragged him back inside and tucked him into bed.

Radioman Ray Daves, 23, relaxes on his bunk, NAAF Cold Bay, winter 1943. (Photos on wall are Adeline Bentz, also 23.) COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

The only normal, legal alcohol you could get at Cold Bay was at the Officers Club. Enlisted men could go there, too, if they were guests of an officer. I usually went with Ensign Bell. He was the base recreation officer, and we were friends. The first time he took me to the O Club, I realized officers weren’t that much different from the rest of us. They sat around, played cards, shot pool, and told jokes. I think they also drank a lot, because I remember what happened when I asked the bartender for a 7-Up. He looked at me kind of funny and said, “How do you mix that?” I never was much of a drinker. I just enjoyed the view from where I stood at the bar. The first time I saw that painting of the girl on the beach, I knew it was “by Hec.” I never asked how much the officers paid him for that mural. Knowing Hector, he probably did it for a ham sandwich and a couple of beers.

The Navy did not send any Christmas trees to Cold Bay, but we did get a planeload of Red Cross parcels, enough for everybody on the base. Counting the officers, there were about five or six hundred of us. The boxes were all the same size—about a foot and a half across—but the contents were all different. It was

kind of fun to see what everybody got, and then we swapped with each other. Mine was full of socks and cigarettes. I also got a package from my mother: a fruitcake with no fruit. The card said she was afraid real fruit would spoil by the time it got to me, so she baked it with gumdrop candies instead. Another radioman got a quart-sized jar of his mother’s home-canned cherries. The way he hopped around Paradise Lost that day, you’d have thought it was a fifth of whiskey. He told us he was going to get drunk on Christmas Eve, and, by golly, he did. We thought he’d lost his brains and got into the torpedo juice, but it was his mom’s home-canned cherries. They were preserved, all right—in bourbon. My mother never would have thought of that. The only time she allowed booze in the house was when the doctor prescribed it for my dad: “Two or three straight swallows at night, to improve the appetite.”

A couple of days before New Year’s, the base commander’s yeoman came running into the radio shack. He hollered at me, “Daves! Daves! Guess what! You made chief!” I thought it was a prank until I saw the papers. Everybody said the only reason I got that promotion was because the war was creating so many new openings. They called me a “Tojo Chief.”17 I suppose that was an insult, but—guess what?—I didn’t care. It nearly doubled my pay.

It would have been a lot nicer if I’d had some place to spend all that extra money at Cold Bay, but there were no stores or taverns or anything like that. Heck, I couldn’t even spend my uniform allowance. The Navy gave me a voucher for three hundred dollars, which was enough for several sets of chief petty officer uniforms in all the different colors. The one I really wanted was aviation green. You weren’t entitled to wear that color unless you flew—all those search-and-destroy missions with Fish were good for something—but there were no uniform shops either.

There were only five or six other chief petty officers at Cold Bay at that time. When they heard I made chief, they gathered up all the different pieces of the uniform I needed. It didn’t bother me to wear hand-me-downs, but those guys were so much taller and heavier than I was. The jacket, the pants, the shirt—everything

was two or three sizes too big for me. The only part that fit was the hat. I knew I looked ridiculous; I felt like a little kid playing dress-up. Maybe that’s why I didn’t get the usual initiation for a new chief petty officer. I guess they thought I’d been humiliated enough.

Shortly after I made chief, the base commander called me to his office. This was the first time he’d ever spoken to me, one-on-one. I thought I was in trouble. When he said, “Congratulations,” I thought it was for making chief. That wasn’t it either. He just wanted to tell me that I was leaving Cold Bay. He didn’t know why, but, for some reason, I had orders to report to the naval air station on Kodiak. Immediately. Well, that was funny. Kodiak was an island in the Gulf of Alaska, less than five hundred miles east of us on the Aleutian Peninsula. But there was no way for me to get to Kodiak. Not in January. None of our planes were flying in the fog, and there were no Navy ships in the area at that time. Lucky for me, that base commander at Cold Bay really did have a lot of connections with the civilian boat captains in the Aleutians. He radioed the captain of the Algonquin and called in a favor. I boarded that ship to Kodiak the very next day.18