KODIAK

January Through December 1944

The Algonquin was about half the size and speed of a destroyer, but we still should have made it to Kodiak in two days. I’m sure we would have if we hadn’t run into a storm in the Gulf of Alaska. I wouldn’t call it a typhoon. It wasn’t even as bad as a williwaw, but it was a pretty good storm. The winds really slowed us down, and on a ship that small, you could really feel the waves. I don’t know why I didn’t get seasick. At least ten guys did, and that was over half the crew. The rest of us went belowdeck and played poker with the captain for the next four days and nights.

I’ve never had such good luck at cards in my life. In one hand of five-card draw, I was dealt ace, king, queen, and jack, all in spades. Lo and behold, I drew the joker. That gave me a royal flush, the highest hand you can get in poker. Luckier still, nobody folded. Everybody at the table must have thought he had the winning hand, so the bet came around to me several times. I just kept raising and tried to look worried until they called. There was over eight hundred dollars in the pot. I even got to

keep most of it. We were only a couple of hours out of Kodiak at the time.

The harbor at Kodiak was full of destroyers. I didn’t need to wait for a jeep at that dock, because the base was right on the water. I saw lots of snow on the ground, but none of that awful wind or fog. Compared to Cold Bay, this was the tropics. The base was about ten times bigger, too, with all kinds of shops and stores.1 First thing I did was find the one that sold uniforms. I bought my first chief’s uniform that actually fit. And then I hit the coffee shop. I was surprised at the prices on the menu: A cheeseburger cost thirty-five cents. Everything was about twice as much as you’d expect to pay in a restaurant on the mainland, but even that was okay. I hadn’t had a burger and fries for so long, I would have paid a quarter just for the smell.

The radio shack on Kodiak was next to the runways. All the planes I saw taking off and landing were Navy, but they weren’t carrier bombers or fighters. They were PBYs. I did see a few other planes with Army Air Force markings, all parked in plain sight outside the hangars. The radiomen said they were too damaged or obsolete to fly in combat. They were just decoys, for drawing the first fire from a Japanese carrier attack. No one thought this was very likely, and they didn’t seem too worried about an enemy invasion on the ground either. According to the radio gang at Kodiak, the only major threat to us in Alaska at that time were the Japanese submarines.2 I was kind of looking forward to flying submarine search-and-destroy missions out of Kodiak on a PBY—they were a lot bigger and faster than the Kingfishers at Cold Bay—and I was really disappointed when the communications officer told me I couldn’t. He didn’t need any more gunners. What he needed was an assistant communications officer, and I was it. My official job title was NCOIC, for “noncommissioned officer in charge.”

Lieutenant Commander Meeker was the commissioned officer in charge. Everybody liked him, but we called him “Beeker.” That’s how it sounded when he said his name. He had a chronic sinus condition, from allergies or something. Meeker’s worst

problem was that he didn’t know squat about the latest technology in communications equipment. He’d been in the reserves for years before he got called up to active duty because of the war. I’m guessing the Navy assigned me to assist him because I was less than a year out of Radio Materiel School. I was okay with that. In fact, I liked being Meeker’s right arm. He gave me a lot of authority over the lower-ranking enlisted men, and he seldom interfered with my decisions. We got along just fine.

The one thing Meeker could not give me was a thirty-day leave. Wanting to go home and get married was not an emergency, and those were the only kind of leaves the base commander at Kodiak was approving at that time. I did get the job of escorting a prisoner to Seattle. I don’t know what that poor sailor did, but he was handcuffed to my wrist when we boarded the plane, and the key stayed in my pocket the whole trip. I couldn’t even let him go to the bathroom by himself. We made small talk during the flight; he seemed like a really nice guy. Probably got drunk and hurt somebody in a fight. I didn’t ask. I just turned him over to the Shore Patrol at Sand Point and called Adeline.

Her boss at Fort Wright was even nicer than mine. He gave her three days off, and she caught the next flight to Seattle from Spokane. I was out pacing on the runway when that DC-3 came in with one engine on fire. I will never, ever forget that sight. I truly thought her plane was going to explode before it touched down, and there was absolutely nothing I could do to stop it. I just watched and prayed and praised God when it did not. Adeline asked why I was shaking when she hugged me. I told her I was just nervous. I was afraid she would never fly again if she knew the truth.

We spent the next three days together in Seattle. I would have preferred to spend the nights with her, too, but she said, “No, Ray. We’re not married yet.” So then I offered to buy a marriage license and find a justice of the peace, but she wouldn’t go for that either. Adeline wanted a regular church wedding in her hometown. There was no sense arguing with that girl, especially when I knew she was right. We stayed in separate hotel rooms.

I got another special assignment as soon as I returned to duty in Kodiak. Meeker wanted me to start meeting the planes that brought in the USO entertainers. About once a month, they came and put on a show for us. I never saw any big movie stars like Bob Hope—I heard he was there before I got to Kodiak—but I sure did see a lot of other comedians and pretty girls.3 I helped them get their luggage off the plane, showed them to their quarters, and gave them tours of the base. Sometimes I stayed backstage in case they needed anything during the shows. The way those sailors hooted and whistled, you’d have thought the girls were strippers. They most definitely were not. They were just a bunch of really nice girls who could sing and dance. Not one of them ever acted like she was offended, though. I guess they were used to it. I’m sure the USO girls realized that there were probably a lot of guys in the audience who hadn’t seen their wives or girlfriends since the war started.

Thirty-day leaves were fairly rare during the war, no matter where you were stationed. If you weren’t sick or injured—or lucky enough to survive when your ship went down—you might get a day or two on liberty now and then, and that’s all. So I really don’t know how Meeker managed to get one for me in late February, but he sure did. I grabbed my seabag and caught the next plane out of Kodiak before the base commander could change his mind. I landed in Seattle on a Wednesday night, called Adeline, and asked her if she still wanted to get married. She picked me up from the airport in Spokane on Thursday morning. She said she already had her dress, and she’d already spent most of my poker winnings from the Algonquin on silverware for her hope chest. There wasn’t much left for me to buy her a wedding ring, but she thought it was pretty. If you held it up to the light just right, you could almost see the diamond.

There was considerable discussion about the wedding cake. What with the wartime sugar rationing, Adeline’s mother had to call several bakeries before she found one with enough sugar on hand to make the frosting. I couldn’t understand why she was so riled up. She had all day Friday to phone all the friends and relatives

she wanted to come to the wedding on Saturday. I don’t remember much about the ceremony, but I know that we spent our first night together at a hotel in Spokane and boarded a train in the morning. I did pay extra for a berth in the sleeping car that time, and, oh yes, we had a beautiful trip, all the way to Arkansas. I’m sure the scenery was nice, too.

My parents picked us up at the train station in Little Rock. I thought it might be a little awkward when they met Adeline for the first time, but it really wasn’t. She just melted right into my family. The only thing that made me nervous was when she started talking politics with my dad. I should have warned her about that. Dad was a real strong Democrat, and so was everybody he knew. One of the biggest newspapers in the state was called the Arkansas Democrat, so that tells you something. Well, Adeline thought the Republicans were better. I held my breath when she asked him, “So, A.V., just what would a person do if they weren’t a Democrat in this part of the country?” I was shocked when he said, “You’d keep your damn mouth shut, that’s what!” But then he winked at her, and they both burst out laughing. As far as Mom and I knew, this was the first time anybody had ever disagreed with A. V. Daves on politics and made him laugh at the same time.

We spent the rest of my leave going to one family reunion after another. All of the relatives in Vilonia and Conway and Little Rock wanted to meet Adeline and wish us well. The most special day for my mother was when she had all seven of her kids home at once. Five of us were in uniform. A lot of families had that many or more in the military during the war, so there was nothing unusual about that. It was just rare to see all five of us together in the same place on the same day. Verna was on liberty from the Army hospital in Hot Springs; Lloyd and Velton were in the Army, too. They were both expecting to ship out for Europe in a week or so. Our younger brother Max followed me into the Navy. He was fresh out of boot camp. We all swore not to talk about the war while Mom was around, and we didn’t. But she still cried some that day.

An American family in uniform during World War II. From left, Ray Daves, 23, Navy; Velton Daves, 26, Army Air Force; Verna Daves, 30, Army Nurse Corps; Lloyd Daves, 28, Army; Max Daves, 17, Navy. Vilonia, Arkansas, March 1944. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

Adeline was crying when I left her with her parents on my way back to Kodiak. I thought it would be easier to be away from her after we were married, but it was worse. Much worse. I don’t believe I ever cursed the war as much as I did then. The only thing that kept me from going crazy was the work that piled up on my desk while I was gone. Some of the reports I had to write required the signature of a commissioned officer, so Meeker got the base commander to make me an ensign. He called it a field commission. There was no ceremony, and my job didn’t change. I just got paid more for it. And then I had to go out and buy another set of uniforms. Commissioned officers’ jackets had six buttons instead of eight.4 If you define a mustang

as an enlisted man who gets promoted to commissioned officer, then I guess I was a mustang. I never thought so, because I didn’t take officer’s training and I didn’t go to Annapolis. And, besides that, it was only temporary. Meeker made it real clear to me that I’d get busted right back to chief petty officer if I ever left Alaska. He knew darn good and well that I had already put in a request for transfer to a base on the West Coast.

About a month after I made ensign, Meeker called me into his office and told me to shut the door. That was pretty unusual, so I knew something was up. He said we were getting a new radioman on our staff at Kodiak, and he was colored. “Colored” or “Negro” was how the Navy referred to African Americans at the time. Meeker wanted to know if I had a problem with that. I was shocked. I didn’t know what to say. I couldn’t think what I had ever said or done that would cause my commanding officer to ask me such a question. But then I realized he didn’t really mean to insult me. He just made the mistake of assuming I was prejudiced because I was from the South.

Well, I have to admit, there was such a thing as Jim Crow laws in the southern states.5 We even had one in my hometown. Believe it or not, it was against the law in Vilonia, Arkansas, for “colored” folks to be out on the streets after dark. My dad told me that. But he also said that this law had never been enforced, so far as he knew. If anybody had ever tried to, I think Dad would have organized the protest. My parents didn’t believe in any of that racist nonsense, and they wouldn’t tolerate it from any of us kids. I guess it all depends on how you’re raised.

As far as I know, the newest member of the radio gang at Kodiak was the first and only African American on the whole base, and I was the first to meet with him on the day he reported for duty in the spring of 1944. He was a third class petty officer, just graduated from radio school. He seemed a little nervous about that, too. I told him not to worry. All I cared about was whether he could carry his share of the weight as a Navy radioman. He thought he could. He said he used to be a chef at some fancy restaurant in New York City until he got drafted. We had a

pretty good laugh about that. He knew as well as I did that the Navy was just getting used to training African Americans for something besides cooking.6 So what does the Navy do when they get a really high-class civilian chef? Why, send him off to radio school, of course. We couldn’t either of us figure that out, unless maybe it was because the Navy needed radiomen more than they needed gourmet cooking at the time. Whatever. I gave him a shift, told him to do his job, and let me know if anybody gave him any grief.

I never got to be friends with that man—the Navy frowned on socializing between the commissioned and noncommissioned officers at Kodiak—so I can’t say what it was like for him outside of the radio shack. I do know that he bunked with all the other enlisted radiomen, and I saw him eating and talking with them in the mess hall.7 I heard he wasn’t much of a poker player, but he really was a talented chef. On his days off, he would walk down to the docks and fish for salmon. Whenever he caught one, he cooked it up and shared it with us. The regular cooks let him have the run of the mess hall kitchen any time he felt like it. I suppose they thought it was a privilege to watch how he seasoned all the different dishes. He was a darned good radioman, too.

I was still at the base on Kodiak when we heard about the D-Day in France. To us, this was no more or less important than all the other D-days we’d had with the Japanese all over the Pacific since the attack on Pearl Harbor. The first day of any military offensive was called D-day. I didn’t begin to pay extra attention to this one until I saw the numbers.8 And I just knew my brothers were there. All summer long, I was looking at the casualty reports from Europe, and I was scared to open my mother’s letters. I was afraid that she would tell me Lloyd or Velton had been killed in action. She didn’t know if they were dead or alive for months after D-Day. There was no news from either of them until she finally started getting letters again in the fall. They couldn’t tell her where they were, of course. The family just assumed they were on the move with the Army, somewhere in France or Belgium.9

I wasn’t allowed to tell anyone what I was doing in Kodiak that summer either. Our business with the Russians was still a pretty big secret at the time. I never quite got used to seeing their planes touch down on our runway. There were usually about a dozen Russian pilots on board, and Meeker assigned me to meet them, too. After I showed them to their quarters, we usually had dinner together in the officers’ mess. It was my responsibility to make sure none of those Russian officers walked around the base without an escort. It was an odd situation for them and for us. We knew we were allies against the Germans, but I don’t think either of us knew if we were really “good” allies. I’m guessing their orders were exactly the same as mine: “Be cordial; be careful; make small talk.”

As soon as the Russian pilots were trained to fly our bombers and fighters, somebody painted over the American markings, slapped on the Soviet Union’s red star, and off they went. I have no idea how many planes we handed over to them while I was at Kodiak. Hundreds, at least. Maybe thousands.10

The only Russian officer I got to know fairly well was “Lieutenant B.B.” He wasn’t supposed to give me his full name. B.B. was one of the few who spoke English fluently, and also one of the few who came to Kodiak more than once. It was kind of a strange friendship, I guess. When he and I had dinner together, we talked about our wives and families back home, and how much we wished the war was over so we could see them. I was surprised when he slipped and told me that the Russians knew about our new radar equipment. The Kodiak radar was really state of the art in 1944. We could pick up a formation of planes halfway between Hawaii and Alaska. When my Russian friend asked permission to see it, I had to say sorry. I couldn’t even show him which building it was in. I think I made it up to him, though: I took him backstage after a USO show. He got such a kick out of that, he let me take his picture with the girls. After that, he even told me to go ahead and take one of him with all the other pilots as they were leaving. I have never known if Lieutenant B.B survived the war; I have always hoped that he did.11

I wish I could have gotten a picture of President Roosevelt. My dad would have loved that, but I didn’t even know the President was on Kodiak until after he was gone. He must have come by ship—I’m sure I would have seen him if he’d landed on our runway. Nobody I knew caught so much as a glimpse of him, coming or going, so it must have been a pretty low-key event.12 I never idolized FDR as much as my parents did, but I did think he was a great Commander in Chief during the war. I would have voted for him if I’d had a chance. I don’t believe anyone in the radio gang at Kodiak was a registered voter in the fall of 1944. If it was possible for us to vote in that election, the word never got around.13

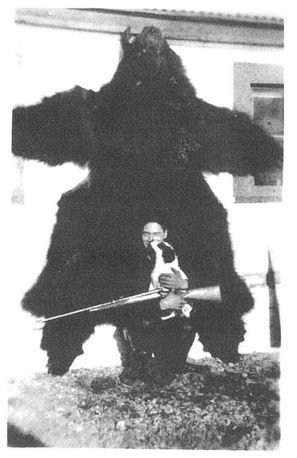

I did do a little bit of sightseeing on Kodiak, thanks to the hunting guides on that island. I got acquainted with several of them while they were out on the runway, waiting for the commercial planes to bring in another batch of tourists. One guide invited me to spend a liberty at his hunting lodge. I wasn’t interested in going out with the tourists that came to hunt the Kodiak bears—never saw the point of killing any animal that I didn’t plan to eat—but I did take advantage of the free room and board, and it was fun to walk around the town. Kodiak Town was very small. It reminded me of my hometown in Arkansas, and so did the school. The children were outside for recess, and they all wanted to come and talk to me. Their teacher was close by. She said it was good for them to practice their English on somebody from the mainland. The kids were very curious. I don’t think they were used to seeing sailors in the residential part of town. When I told them it hardly ever snows in Arkansas, they thought I was joking.

An American bomber, recently painted with the USSR’s red star, was one of thousands transferred to the Soviet Air Force during World War II. All photos of these transactions were forbidden by both countries until July 1944. (In this group of Russian officers and pilots at Naval Air Station Kodiak, Alaska, “Lt. B.B.” is second from right May 1944.) COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.

My request for transfer to the West Coast came through in December.14 The Navy had an opening for an instructor at the radio school in San Diego, and I took it. I knew it meant a cut in rank and pay—from ensign back to chief petty officer—but I didn’t care. If they wanted to bust me down to apprentice seaman, with leggings, I probably would have said okay. It’s not that I didn’t like my job on Kodiak. I really did, and the weather was pretty mild, too, for Alaska. I just wanted to be somewhere closer to my bride. I was in San Diego when I called her on New Year’s Eve.

A hunting guide displays hide of a Kodiak bear at his hunting lodge, Kodiak, Alaska, 1944. COURTESY OF RAY DAVES COLLECTION.