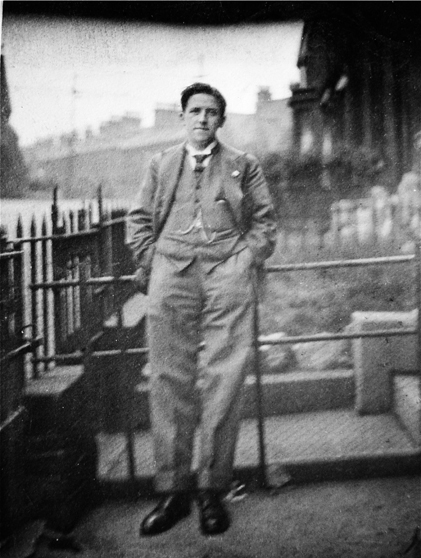

Kenneth and Laura Hockney’s wedding, 1929 (illustration credit 1.1)

The life of David Hockney almost ended when it had barely begun. Sometime in the small hours of 31 August 1940, a German bomber on a raid over Bradford in West Yorkshire released a stick of bombs, one of which fell on Steadman Terrace, a steeply inclined street on its northern outskirts. In number 61, the second house from the top, the seven members of the Hockney family and their neighbour, Miss Dobson, were huddled in a tiny space beneath the stairs, barely seven foot long. As the bomb came down, filling their ears with its high-pitched whistle and electrifying them with fear, three-year-old David’s older brother Philip clambered over his siblings, threw his arms round their mother and cried out, “Mum, say a prayer for us.” Laura Hockney clutched at a small “promise box” containing verses from the Bible before being hurled forward by the force of the bomb as it exploded, letting out a piercing scream that her children were never to forget. A timber merchant at the bottom of the street had taken a direct hit which all but destroyed it and left the road littered with wood. Every house in the street had its windows broken or the roof damaged. Yet miraculously number 61 was untouched. Forever after Laura was convinced it was the promise box that had protected them.

Kenneth and Laura Hockney’s wedding, 1929 (illustration credit 1.1)

The city in which the family huddled that night, and in which David Hockney had been born three years earlier, on 9 July 1937, was the thriving centre of England’s wool trade, with a population of close to 300,000. Commonly thought of as a Pennine town, like its neighbours Halifax, Wakefield, Dewsbury, Shipley and Huddersfield, Bradford can in fact be considered as part of the Yorkshire Dales, lying as it does in the valley of the Bradford Beck, known locally as Bradforddale. Before the advent of steam, it was a market town with a population who raised sheep, sold home-grown fleeces and made cloth on handlooms. Then came the Industrial Revolution and, benefiting from the water power provided by the many streams rushing down the steep surrounding hillsides, the small town began to grow. As the hills became covered with woollen mills rather than sheep, there was a shortage of local wool, and Bradford looked to the empire for its raw material, importing from South America, India, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia. It was not long before it became one of the world’s central markets for wool and wool products.

The city was immortalised in the popular imagination of the day as “Bruddersford” in J. B. Priestley’s best-selling novels The Good Companions and Bright Day. “Lost in its smoky valley among the Pennine hills, bristling with tall mill chimneys, with its face of blackened stone,” wrote Priestley, “Bruddersford is generally held to be an ugly city; and so I suppose it is; but it always seemed to me to have the kind of ugliness that could not only be tolerated but often enjoyed.”1 Travellers on the London Midland railway, perhaps following in Priestley’s footsteps, would have spilled out of the Exchange Station to find themselves in the heart of the city, in an area dominated by public buildings such as St. George’s Hall, where Dickens gave his first reading of Bleak House; the Wool Exchange, a great Gothic-revival building with a tall clock tower which was the centre of all the wool-trading; and, most striking of all, the Venetian Gothic town hall, with its 200-foot-high tower inspired by the campanile of the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. Whether they would have seen the top of the tower is a moot point, however, for the two hundred or so chimneys of the woollen mills were belching out fumes all day, which sank slowly into the basin in which the city lies, and made Bradford then one of the smokiest cities on earth. “When you come down into the centre of Bradford,” wrote a local author, Lettice Cooper, in 1950, “dipping into that cauldron of smoke, your first impression is that everything is black, everything is solid, every doorway bears some legend connected with wool—‘Wool Merchants,’ ‘Wool Staplers,’ ‘Tops and Noils,’ ‘Textile Machinery,’ ‘Dyers and Spinners Association.’ ”2

Bradford Town Hall (illustration credit 1.2)

Though there was some wool in the blood of David Hockney’s parents, their forebears were engaged in a variety of different professions, beginning with that of agricultural labourer. Robert Hockney, his paternal great-grandfather, was born in Lincolnshire in 1841, one of the twelve children of a farm worker, and his first job was as a carter on an isolated farm at Ottringham in East Yorkshire. By 1881, the agricultural depression had driven him, his wife, Harriet, and their two sons to Hull, where he got himself a job as a “rullyman,” driving a horse and wagon delivering goods to and from the docks. It was a profession he remained in until his death in 1914.

Seeking to better himself, his younger son, James William, David’s grandfather, worked as an insurance agent in Hull, which suggests that he must have been clever as well as ambitious. He also appears to have had little regard for the conventions of the time, since he lived out of wedlock with Louisa Kate Jesney, the daughter of a Lincolnshire farm labourer, for eleven years, during which time she bore him three children. They were finally married in Leeds in November 1903, Louisa being pregnant yet again, and soon after moved to Bradford where their fourth child, David’s father, Kenneth, was born on 9 May 1904.

Everyone who knew Kenneth Hockney had the same thing to say about him, which was that had he had the benefit of further education there was no knowing how far he might have gone. As it was, he was born at a time when the ethos of his class demanded he should get through school and out to work as quickly as possible, and in this the Hockneys were no different from the other families in the neighbouring terraced houses of St. Margaret’s Road. Like his sisters, he left school at fourteen, taking up a job as a telegram boy; it was 1918, and he had already suffered the trauma of seeing his beloved older brother come back from the war a broken man, having been gassed in the trenches.

Kenneth had too much of an enquiring mind to want to spend his life delivering telegrams, and as soon as he was old enough he became a clerk for a local firm, Stephenson Brothers, a company of dry-salters, trading from a large Victorian warehouse, who sold chemical products, and goods such as flax, hemp, glue and dye. His wage was three pounds a week, out of which he paid twenty-five shillings to his mother. One of his first jobs was to sit in a small cubicle at one end of the store and open the container with the money that was catapulted along a wire from one end of the store to the other. It was a mindless activity from which he was able to escape in his spare time when, rather than go drinking down the pub with his father and his brother, who had managed to get a job working in a pawnbroker’s, he pursued artistic hobbies. He took evening classes in art and developed a serious interest in photography, moving on from a box Brownie he had had since childhood to buying a serious quarter-plate camera, complete with tripod and hood, which he took everywhere. He often practised on his colleagues, taking a series of portraits of them at work at Stephenson Bros. The family had moved up in the world, to a more spacious house in St. Andrew’s Villas, Princeville, once a street for the smarter citizens of Bradford; the servants’ bells in the hallway indicated the social standing of its former owners.

Kenneth was carrying his camera when he met Laura Thompson properly for the first time, on a Methodist ramble on the moors. Methodism played an important part in Kenneth’s early life, following his conversion by Rodney “Gipsy” Smith, a celebrated evangelist, at the vast mission, Eastbrook Hall, which was at the centre of the social and religious life of hundreds of local working-class young men. After the Sunday-afternoon meetings, the “Brotherhood,” as they were known, would walk home, crowds of them in their best suits, “their faces radiant with joy, some of them humming over the strains of the last hymn they had been singing, others discussing the address they had heard,”3 a scene that was being repeated outside all of Bradford’s seventy-four Methodist halls and chapels. The Methodist hope was that the experience would have uplifted them so much that it would keep them out of the pubs and clubs that proliferated all over the city, and were the ruin of many poor families, for whom drink obliterated the reality of the appalling conditions in which they worked and lived. Kenneth, a teetotaller, was so inspired by the Brotherhood that he eventually became both a lay preacher and a Sunday school teacher.

Since one of the Brotherhood’s aims was the fostering of a spirit of community, they would organise various social events for this purpose, among the most popular of which were rambles up onto the moors above Bradford. “No Bruddersford man,” wrote Priestley, “could be exiled from the uplands and blue air; he always had one foot on the heather; he had only to pay his tuppence on the tram and then climb for half an hour, to hear the larks and curlews, to feel the old rocks warming in the sun, to see the harebells trembling in the shade.”4 One Saturday afternoon in 1928, Kenneth loaded his camera onto a tram to the Exchange Station, to catch a train up to Ilkley, his intention being to walk to Bolton Abbey, a local beauty spot, to take some photographs. It was pouring with rain when he reached his destination, and as he stood on the platform he noticed a group of four girls laughing and staring at him, two of whom, Laura Thompson and her friend Doris, he recognised from chapel. Realising that they must be on a Brotherhood ramble, he decided to follow them. “He soon caught up with us,” Laura later remembered, “and we all went together. He had this great big box camera which he carried about with him everywhere, and I can remember him putting it down in the wet and taking our photograph, right in front of Bolton Abbey. So he took our photograph and after that he just stayed with us.”5

Laura came from a similar background to Kenneth. Her grandfather, Robert Thompson, was an agricultural labourer at Scarning in Norfolk who fathered eight children and ended up living on poor relief from the parish. His son Charles, Laura’s father, escaped this life of poverty by joining the Salvation Army, and when he was in his early thirties set up as a coal merchant in Bradford. In 1894, he married a fellow Salvationist, Mary Sugden, the daughter of a family of weavers. Laura was the youngest of their four daughters, and by the time she was born, on 10 December 1900, her father was working as a “manufacturer’s carter.” He soon had his own cart and set up as a second-hand furniture dealer. Her earliest memories of home were of a house in Ripon Street. “The house had a central door,” she remembered, “and on one side of it my dad had a second-hand shop, while the other side my mother used as a sweet shop. She made her own jam and sweets and her own bread and she sold them at all hours. There were no opening and closing times, and she did all her baking and cooking in the evenings. Dad was out a lot on his horse and cart, often going to sales out in the country where he would buy furniture. Sometimes he would take me to school on his horse and cart.”6

Naturally clever, Laura won a scholarship to secondary school. She left at sixteen, however, to take up a job as a pattern-maker at Tolson’s, a firm owned by a friend of her father’s. Her sharp mind soon got her promoted to being in charge of the pattern books, earning seven shillings and sixpence a week for an eleven-hour day, from eight thirty in the morning to seven at night. She loved the work, which gave her a wide knowledge about different kinds of cloth, but her happiness was short-lived when a bullying colleague had her pushed out of her job, and put back on to more menial tasks. This deeply undermined her confidence, and the girl’s continuing unkindness became so bad that Laura fell ill with what were then referred to as “nerves,” and she had to leave work. In effect, she had a nervous breakdown and it was a long time before she was able to think about looking for work again.

At the time she and Kenneth met, about eight years later, Laura had returned to work in a draper’s shop in Manchester Road, earning twelve shillings a week. She was happy in the job and it had given her back her confidence. Religion played as important a role in Laura’s life as it did in Kenneth’s. She read the Bible every day, as she had done since she had learned to read, was an active member of the local Methodist chapel and taught beginners’ class at Sunday school. Inspired by seeing her Salvationist parents going out among the slum-dwellers, particularly on Friday and Saturday nights when drunkenness was rife, she harboured a genuine, if secret, ambition to become a missionary. This was forgotten, however, when she met Kenneth and discovered that they had so much in common. Like her, he was an ardent Methodist, and she was impressed at how proud he was to have been converted by “Gipsy” Smith. He too taught at Sunday school, and was a lay preacher to boot. They held the same unswerving views on the perils of drinking and smoking. She decided there and then that she was going to marry him and have a family.

There were, however, one or two problems. To begin with Kenneth’s parents, James and Louisa Hockney, were not religious and were quite unconcerned as to whether or not their children attended chapel on Sundays, a trait she found worrying. Then there was the fact that, while her parents were quite fastidious and kept their house spotlessly clean, the Hockneys were the very opposite. “When I first went to his home,” she later told her youngest son, John, “it was awful. His family lived in St. Andrew’s Villas and we’d been walking out for a while before he took me there. It was a lovely big house, but his mother didn’t see very well and she didn’t hear very well either. I’d never seen anything as grubby and untidy. It was horrible.”7 What she did notice, which confirmed her belief that she had chosen the right man, was how much smarter Kenneth was than the rest of his family, and how much his sisters, Harriet, Lillian and Audrey, admired him. A small man, about five foot four, he was both handsome and dashing, with brown hair and greenish eyes.

Kenneth Hockney was a bit of a dandy, whose strong character was reflected in his clothes. This was the era when Montague Burton stores used to offer a “five-guinea suit for 55 shillings” and every working man had one. The fashion was for three-piece suits, usually worn on a Sunday, but Ken wore his every day. His waistcoats were made with lots of pockets, which were always full of bits and pieces, and he had the knack of brightening up his outfits with his own unique touches, using great ingenuity to look smart on his tiny weekly wage. He bought paper collars from Woolworths, specially manufactured for shirts with detachable collars, and covered them with an adhesive material on which he could paint checks and different patterns, and then easily wipe clean (his white collars, invariably black by the end of the day because of the smog, he used to clean with toothpaste). He would buy plain bow ties, and stick coloured paper dots onto them to add colour to his outfits. His shoes were always beautifully polished, and he never went out without a trilby hat, or a cane, of which he had a large collection, a fashion statement inspired by his great love of Charlie Chaplin.

Laura was soon faced with a dilemma: Ken was somewhat slow in coming forward, a fact that drove her to distraction, and after twelve months of dating and no sign of a proposal, she was unsure of what to do. “There was nothing wrong,” she said, “but there was nothing happening. So one day I went to my mother and said, ‘Is it possible for a girl to say something to a boy rather than for the boy to say something to the girl?’ ”8 Her mother’s advice was that she should write to Kenneth to find out if he felt the same way about her as she did about him. After the letter, things began to move faster, and in June 1929 they became engaged. He bought her a bar of chocolate every week, took her to London to visit the zoo, gave her a leather overnight case and a leather sewing box, and, on 4 August, put down £100 of his savings on a tiny house in Steadman Terrace. They were married on 4 September 1929, at the Eastbrook Methodist Mission, walking down the aisle to the strains of the march from Wagner’s Lohengrin.

Kenneth Hockney, circa 1928 (illustration credit 1.3)

The marriage did not receive the enthusiastic support of Kenneth’s mother, who believed that her elder son, Willie, should have been the first to marry. She was also reluctant to lose the twenty-five shillings she received weekly for Kenneth’s board and lodging. “So because Ken wanted to get married very quickly,” Laura remembered, “she put it around that he’d had to get married because I was pregnant, and there were a lot of people who talked about it.”9 This did little to endear Laura to her new mother-in-law.

Number 61 Steadman Terrace was a typical West Riding working man’s terraced house, in one of row upon row of such houses, built of grey-yellow stone or soot-blackened brick. At the top of a very steep street off Leeds Road, with panoramic views across the city to the Pennines beyond, it was mercifully free from the smog that hung about the lower ground. There was no garden at the front, just steps up to the entrance, while at the back there was a tiny yard, just big enough to hang a washing line and to house a small shed for coal and one for the outside toilet. Laura paid her father a shilling a week to furnish their new home with second-hand furniture from his shop, starting with four dining chairs, two armchairs and a sofa. It was to be their home for the next fourteen years.

David Hockney was Laura’s fourth child, following Paul, born in 1931, when she was thirty (then considered quite old to have a first baby), Philip in 1933 and Margaret in 1935. Four children under seven meant that space was at a premium in the tiny house, a “two-up two-down.” The front room was furnished with the dining chairs, armchairs and sofa, as well as a marble-topped mahogany sideboard and a large glass-fronted bookcase. It also housed a “Yorkist” coal-fired range, upon which water was heated both for washing-up and the weekly bath. There was no bathroom; instead, the kitchen or the back room was dominated by a large wooden board used in the week for storage space and for preparing food, then lifted up on Friday nights to reveal an enamel bath. Friday night was bath night, and wartime restrictions dictated that everyone shared the same water. After Kenneth and Laura, the boys all got in the bath together, while Margaret, being a girl, had the luxury of having it to herself. The waste water was used to flush the outside toilet, known as a “Tippler.” On the upper floor, there were two rooms, one shared by the parents, the other by the children.

Money was as tight as space, the only income in the family now coming from Kenneth’s three pounds a week job at Stephenson Bros., where he had graduated to the accounts department. Every weekday morning he would leave home, walk down the hill to Leeds Road and catch a tram to Listerhills, where the business was based. Laura stayed at home looking after the children, cleaning, cooking and sewing. She made all the children’s clothes. If she took them out to the country at the weekends, she had them all foraging for wild berries and salad leaves, and in the spring she would bring back bundles of young nettles to make non-alcoholic nettle beer. When David once sprained his ankle and had to be off school for a couple of days, a friend came to the house to visit and found him sitting with his foot in a bath of foul-smelling liquid. “If this was in medieval times,” he told him, “your mother would be burned as a witch!”10

In the evening, Kenneth would return home and the family would sit down together for tea. On Saturdays there were trips into town to look at the shops in the Swan Arcade, an elegant Victorian shopping arcade, with stone and ironwork swans incorporated in its Market Street entrance, or a visit to St. John’s Market to watch the salesmen give their various spiels, and eat a plate of peas with mint sauce. For a special treat, they might go to Robert’s Pie Shop on Godwin Street, celebrated for its meat-and-potato pies, and for the giant pie, nicknamed “Bertha,” which was always in the window, and which was, as Priestley wrote, “a giant, almost superhuman meat pie, with a magnificent brown, crisp, artfully wrinkled, succulent-looking crust … giving off a fine, rich, appetising steam to make your mouth water … a perpetual volcano of meat and potato.”11 In the summer, they sometimes took a tram ride to Roundhay Park in Leeds, or went for a picnic at a local beauty spot like Shipley Glen, which had a little funfair with swings. Sundays were reserved exclusively for chapel. With the baby David in a pram, the whole family, in their best clothes, would walk down the hill to Leeds Road, to Eastbrook Hall Methodist Chapel for the Sunday service, and back home for lunch. In the afternoon, Kenneth would attend the Brotherhood.

In spite of their relative poverty, there was never any feeling among the children that they went without. On Sunday afternoons, for example, Laura instituted a tradition whereby, as soon as they went off to junior school, each of them could invite four or five friends for tea. “My mother did all the baking,” remembers Hockney, “and Sunday teas were big, with cakes and buns and jelly all laid out on the table. We thought they were terrific.”12 His brother Paul remembers “this one friend of mine, Duncan. When we used to go to his house, all his mother used to give us was two sardines on a plate on a piece of lettuce, and when he came to our house for tea he thought it was wonderful—it was a real feast. It might have been plain stuff, but there was always plenty of it and she always made it herself.”13 Being a girl, Margaret benefited less from these teas than the boys, as she was always required to help.

What mattered to Kenneth and Laura more than anything, how-ever, was education. The children started their school life aged three in the babies’ class at Hanson Junior School, a ten-minute walk from Steadman Terrace, and were encouraged as they grew up to work hard in order to better themselves, under the close and united eye of their parents. Kenneth and Laura, too, continued to learn from everything they saw around them. They both had a healthy respect for culture. Laura was a keen reader, and there were always books in the house. Kenneth had never stopped educating himself, visiting museums, the theatre and opera, reading anything he could get his hands on and taking advantage of any experience that came his way; in 1927 he travelled to Giggleswick, for example, when the Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Dyson, set up camp in the school grounds to observe the total eclipse of the sun. He was a member of the Bradford Mechanics Institute in Bridge Street, which had a library with a large selection of daily newspapers. Kenneth paid them five shillings a year to let him take away all their papers after two days, and he read these voraciously. The world was in a state of upheaval and being a very religious man with a natural inclination to take up extreme causes—he became a member of the Independent Order of Rechabites, a strict anti-alcohol society—he found himself deeply affected by accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and fearful that the unfolding events in Hitler’s Germany might lead to another world war; his brother Willie was a constant reminder of the horrors that that might unleash. Though he never actually joined the Communist Party, he was fired by its ideals. He stopped attending chapel, and became vehemently anti-war, announcing in September 1939, when war on Germany was finally declared, that he was a conscientious objector and would not fight. He adopted a position of moral absolutism, and refused to engage in any work for the war effort, even working as a fire warden.

This was an impossibly difficult time for Laura, seven months pregnant with her fifth child. As a “conchie,” Kenneth was an outcast in a world that was convinced of the rightness of going to war. He was physically attacked at work, and found himself ostracised wherever he went. People spat at him in the street and scarcely a morning went by without Laura having to scrub away the words YELLOW HOCKNEY painted during the night on the front steps by one of their neighbours, a policeman. Philip began to suffer from recurring nightmares. “I used to dream,” he remembers, “that the Germans had landed and had herded all the children onto a piece of land, and were asking, ‘Who is going to protect the children and who is not,’ and my father would always say, ‘I can’t fight,’ and I thought, ‘We’re not going to be protected,’ and would wake up night after night terrified.”14

It was especially hard for Laura because Kenneth’s refusal to fight meant that she received no war pay, while his rejection of any kind of work connected to the war meant that there was no other money coming in, when they needed it more than ever. A yawning gulf opened up between them. “He refused to do any fire-watching,” she later commented, “which he could have done really even if he was against the war. My way of looking at it then was that he could have been protecting his children, and he would have got five shillings a night, which was a lot of money and would have helped us a lot. He wouldn’t talk about it at home … He didn’t share his troubles, and I think if he had done it would have been much nicer for us. Perhaps I would have understood things better.”15

To begin with, the children were spared the knowledge of what was going on, because, since the authorities were convinced that Bradford was sure to be bombed, it was thought safer to evacuate the family until the new baby was born. While Kenneth remained in Bradford, the heavily pregnant Laura and their four children were sent to Nelson in Lancashire. A bus took them from the train station to a local school, where they waited with hundreds of other evacuees to be allocated to local families. Paul and Philip, dressed in little red blazers, with white shirts and socks, and navy-blue trousers, all made by Laura, went first. “We were sitting on this kind of grass verge,” Paul remembers, “waiting to be allocated somewhere and this lady came by in a car and she said she’d take two little boys. So they gave her Philip and me. She just took us off and that was it. We’d never been in a car before.”16 Nobody wanted a pregnant woman with two small children, so Laura was the very last person to be chosen, and then only reluctantly, by a woman who was mainly interested in the food she had brought with her—a carrier bag given to each family by the authorities and filled with corned beef, cocoa, dried milk and tea. Her name was Mrs. Lund, and she lived across the road from the school with her husband and daughter, both of whom worked in the local woollen mill. “She was a very strict person,” said Laura, “but very kind.”17 The Hockneys were given a room with a double bed for Laura and Margaret, and a cot for David. They sat at the same table as the Lund family, but cooked their own meals, and Kenneth was allowed to visit once a week. It was not mentioned that he was a conscientious objector.

Two weeks after the birth of the new baby, a boy they named John, Laura and the children returned to Bradford and David was enrolled in the babies’ class at Hanson. Because of the blackout, wartime school started late and finished early and it was drummed into the children that if the air-raid sirens started while they were on their way to school or home, then they should run as fast as possible back to whichever was nearest. The school day was also punctuated with routines like the daily gas-mask practice. All the children, of whatever age, had to have a gas mask and know how to put it on, and they were given little cardboard boxes to carry them in. To Laura Hockney, these did not seem quite good enough, so she made her children special leatherette cases to provide adequate protection in the rain. They never actually had to wear one.

With no job and no prospect of any other kind of employment, Kenneth was thrown back on his wits. He had always been good with his hands so he decided to start a little business reconditioning prams, both dolls’ prams and babies’ prams, which he found through the advertisements in local papers, like the Bradford Telegraph and Argus, or the Dewsbury Gazette. Laura put her dressmaking skills to use repairing or remaking the hoods and aprons, while Kenneth put new springs on them and painted the bodies to make them look new. Though this work brought in relatively little money, with careful use of her ration books, Laura was able to make ends meet. A family of seven was allowed one book for each member of the family. She had three books for meat, and since she was a strict vegetarian, all her ration went to the children. With the other four books, she could get plenty of cheese, milk and butter or margarine. “She was very good at feeding us,” Margaret remembers, “and she certainly didn’t expect us to be vegetarians, though she did make very nice vegetarian food.”18

The family had scarcely been back a few months when the bomb struck that nearly annihilated them. It was one of 116 bombs dropped on Bradford that night, doing considerable damage to the city centre and surrounding areas. Lingards, the great department store, took a direct hit and was gutted, as was the adjoining Kirkgate Chapel. Rawson Market was badly damaged, and in Manchester Road a bomb crashed through the roof of the Odeon Cinema, then the largest in Britain, landing in the front stalls and bringing the ceiling and heavy metal chandeliers down onto the seats. Miraculously, the audience for It’s a Date, starring Deanna Durbin and Walter Pidgeon, had left ten minutes earlier. Robert’s Pie Shop had its front blown off, but when Priestley visited the city a month later, at the end of September, just after the Battle of Britain had been won, the giant pie was back in the window, still steaming, “every puff defying Hitler, Goering and the whole gang of them.”19

Then, quite suddenly, in 1943, Kenneth announced that they were moving house, a decision which angered Laura, who had not been consulted. Kenneth’s reasoning was that, with five children, they needed more space, and that it would be good for the whole family to get away, since the cruel taunts of their neighbours in Steadman Terrace were not going to cease. The new house, 18 Hutton Terrace, was in Eccleshill, a suburb high up on the northern outskirts of the city. It had a proper cellar, a kitchen with an open range for cooking, and a separate front room. Upstairs there were two bedrooms on the first floor and two attic rooms, and it had a bathroom and an inside toilet. There was a decent garden at the back, the air was fresh, and the front looked out over green fields, with extensive views across the Aire Valley. It was certainly a good environment and in time, Kenneth believed, Laura would come round to it, but night after night Margaret, who had the room next to them, would hear them arguing into the small hours.

Kenneth set up his pram business in the cellar of the new house, and with the extra space it afforded, he also began to buy and restore bicycles. When work was completed and they were ready to be sold, he would advertise them in the local papers, giving the number of the nearest telephone box and telling prospective buyers to call it between a certain time. Then he would take his favourite chair and set it up outside the box and sit down and wait till somebody called. For the young David, this seemed logical. “People considered him eccentric for doing this,” Hockney says now, “but it just made me think…‘What a sensible man. That’s just what I’d do.’ ”20

It was in his father’s pram workshop, watching him at work, that the seeds of Hockney’s ambition to become an artist were sown. “The fascination of the brush dipping in the paint, putting it on,” he later wrote, “I loved it … it is a marvellous thing to dip a brush into paint and make marks on anything, even on a bicycle, the feel of a thick brush full of paint coating something.”21 And on another occasion he recalled how “he’d put silver paint on the wheels, but the one thing I remember was he’d paint a straight line down the bar. He had a special brush and he would hold his finger along the brush so he could paint a perfect line. I thought: incredible that you can make a straight line like that with just your eye. It’s like watching Michelangelo draw a circle.”22

The young Hockney drew from the moment he was old enough to hold a pencil. “My earliest memory of David drawing,” recalls John, “was when we used to get up in the morning and I used to come down to get my comics or the newspaper. The edge all the way around, where there was no writing, was usually covered in little drawings and cartoons. That was the only paper he could get, and this was before school every day and he’d already be drawing. I used to get annoyed because I was looking forward to getting my own comic and he had already drawn all over it.”23 If he couldn’t get hold of a scrap of paper, he would draw with chalk on the linoleum floor of the kitchen, and when his mother got fed up with the mess she put up a blackboard. The golden rule was “No drawing on the wallpaper!”

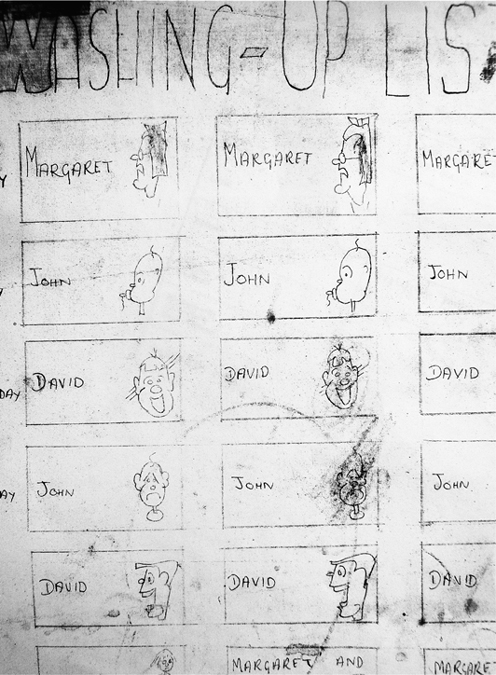

On Saturday mornings Hockney would enter the painting and drawing competitions for children that used to appear regularly in the Daily Express, and when the family went on Sundays to their local Methodist church in Victoria Road, he would doodle away on the fly leaves of the hymn books. After chapel, there would be Sunday school, at the end of which the children were broken up into small classes and asked to do illustrations of what they had learned. Hockney used to draw cartoons of subjects such as “Jesus Walking on the Water,” much to the amusement of the rest of the class. At one point his mother arranged for him and Margaret to have piano lessons. “After the third lesson,” he remembers, “I thought to myself, ‘I’m going to have to put an awful lot of time into this,’24 so I said to my mam, ‘I’d rather put my time into drawing.’ So I gave up. My parents always encouraged me with my drawing.” They also put it to good use. When Laura drew up a washing-up rota, David illustrated it with caricatures of himself and his siblings in various moods, of which he was the eternally cheerful one.

The children’s new school was Wellington Road Primary, and on 8 May 1945, a two-day holiday was announced to the children there—the war was officially over. Hockney rushed home to tell his mother who already knew from listening to the radio, which was kept on permanently. It struck his eight-year-old self, as he looked at the large console and the coloured map of Europe above it, on which they had followed the progress of the war, that from now onwards there would be no more boring news coming endlessly out of the radio, but just music and songs. “When the blackout was over,” he remembers, “and the lights came on again, Bradford Corporation Buses organised a bus route that took you along the hills round the edge so you could see the city lit up. Well, it was probably a pretty miserable sight, but to a small kid this was like Las Vegas.”25

Many of Hockney’s early influences developed during this period. “He always seemed to be worldly-wise at a very young age,” Margaret remembers. “From the age of five or six, he seemed to know what to do in the world. He really enjoyed life.”26 With Eccleshill Library nearby, the house was always full of books and he read a lot, everything from Biggles to the Brontës, the local classics, to Dickens. His father took them all to museums, and to look at the collection of Victorian and Edwardian paintings in Cartwright Hall, the civic art gallery in Lister Park. On Saturday nights they would often go to the Alhambra Theatre in Morley Street, taking fish and chips up to the balcony, where they’d have cheap standing tickets at the back. Though pantomime and music hall were the usual acts, there were the occasional more upmarket evenings, on one of which Hockney saw his first performance of Puccini’s La Bohème, performed by the Carl Rosa Opera Company. “It stuck in my mind,” he recalls, “because it was about artists in Paris, and the music was better than usual and the orchestra was bigger. My father didn’t really care for it. He just said, ‘Well, some nights it’s like that …’ ”27

First and foremost, however, Hockney loved the movies, his early experiences of them being during the war when, because of the blackout, to get to the cinema they had to feel their way down the street by running their hands along the wall. It was a passion he inherited from his father. “I used to say, ‘Can we go to the pictures?’ ” he remembers, “and my dad used to say, ‘You’ll have to ask your mother.’ And we knew that was fatal, because she ran everything and she didn’t like the pictures. She was very much in charge, and if she said no that meant no. I suppose she was worried about the expense.”28 For that reason, on the occasions when Laura relented, they never went in the main entrance of the cinema, but in the side entrance for the cheap seats at the front. And there were ways to get in free. Kids would often manage to push open the exit doors to let in their friends waiting outside, while Hockney remembers learning “that if you walk in backwards, people think you’re coming out.”29

“Untitled” (date unknown) (illustration credit 1.4)

In the 1940s Bradford had more than forty cinemas, or “picture houses.” The Arcadian and the Empress, the Odeon and the Coliseum, and the New Victoria, which stood next to the Alhambra and had the third largest auditorium in the country, showed first-run films. Then there were the “fleapits” like the Oxford, the Elysian and the Idle, which had a sheet for a screen, and films that were likely to be very scratched and have poor sound. Because by the mid-1940s he was beginning to go deaf, Kenneth sought out cinemas with the state-of-the-art Western Electric Sound System, which gave a sharper sound. The films they showed were invariably American. “I was brought up,” says David, “in Bradford and Hollywood, because Hollywood was the cinema. American films were technically superior, because they had good lighting and good sound.”30

Saturday mornings meant Kids’ Club at the Greengates Cinema on New Line, where David and John watched serials such as Superman, Flash Gordon and Hopalong Cassidy. “There was excitement on that screen,” Hockney later wrote. “The screen, as if by magic, was opening up the wall to you. It showed you another world, even in the dingiest little cinema in suburban Bradford.”31 He also shared his father’s love of what Kenneth referred to as “comical” films, starring Charlie Chaplin or Laurel and Hardy. “He used to laugh so hard,” Hockney remembers, “that it loosened his false teeth.”32

Though Bradford is an industrial city, it is small, and to the north and the west there is beautiful countryside that can be reached very quickly. From an early age, the young David was an avid hiker and cyclist. A tuppenny bus ride would take him to Saltaire where the great mill built by Sir Titus Salt belched out smoke, and from there it was a short walk to Shipley Glen, with its funfair, or a three- to four-hour hike to Ilkley, fifteen miles away and advertised for its “bracing air.” With Kenneth’s help, David and John built themselves a tandem from second-hand parts and they would cycle all over. York was a favourite destination because, once they’d got through the hilly country around Leeds, the journey was all on the flat. They’d set off at eight in the morning and it would take them four hours. Once there, they would climb the tower of the Minster, walk the city walls or visit the railway museum before returning home. Sometimes they went to Leeds where there was a much bigger art gallery that had French paintings, and there were stores such as Woolworths which had modern cafeterias. “Some of the trams in Leeds,” Hockney remembers, “had New York Road written on the front, meaning the new road to York, but I used to think, ‘New York! You’d never see that written in Bradford.’ ”33

Very occasionally Kenneth took the whole family on a summer holiday, but while most people went to Morecambe or Blackpool, for which the Hockney children yearned, they went to Withernsea. There were two reasons for this. First of all it was close to Hull, where they could stay with their Great-Aunt Nell, their father’s aunt, an eccentric woman who adopted an exaggerated “posh” accent. Second, it was cheap, a short bus ride from Hull and there was nothing to spend their money on when they got there. “All Dad had to do was give us a few pennies, because there was just one tiny little arcade. I mean, compared to Withernsea, Bridlington was like Monte Carlo, which is why we weren’t allowed to go there.”34

When he was at home, he was encouraged to study at all times. So far as his parents were concerned, it was Bradford Grammar or nothing, and his school reports show what achievements he made. In February 1946, when he was fourth in his class of thirty-six, his headmaster, Irvine R. Bakes, wrote: “David has shown great interest in his work. He tries at all times.”35 The next term he had reached top place with an overall score for all his subjects of 274 out of a possible 280. “David has done excellent work this year,” wrote Mr. Bakes. “I could do with more like him.”36 This was in spite of the fact that he had had to scold David in front of the whole class for sketching the teacher during the problem exam, something he had been caught doing on several other occasions when he was bored in class. Drawing in class did not stop him soaring ahead, however, and the following year, at the end of the summer term, his work was judged “Excellent throughout the term. All subjects reach a high standard. Outstanding in art.”37 Parents of children at Wellington Road were encouraged to sign off the reports, with a view to encouraging their children in their work at school. “I am very pleased with his progress,”38 wrote Laura Hockney.

This was a time when the education system in Britain was being revolutionised. Hockney and his generation were the first beneficiaries of the 1944 Butler Act, a landmark in English education which greatly expanded access to secondary education by making it free for all pupils. “The throwing open of secondary education to all,” wrote Harold Dent, the editor of the Times Educational Supplement, “[would] result in a prodigious freeing of creative ability, and ensure to an extent yet incalculable that every child shall be prepared for the life he is best fitted to lead and the service he is best fitted to give.”39 Pupils were assessed in a new exam, the eleven-plus, intended to allocate them to schools best suited to their abilities and aptitudes.

All Hockney’s hard work paid off when, in the spring of 1947, like his brother Paul before him, he won a scholarship to Bradford Grammar School, one of the oldest academic institutions in the country, founded in 1548 and granted its charter by Charles II in 1662. For parents like his, with their great ambition for their children, this was manna from heaven. Such schools were known for their high academic standards, emulating the curriculum, ethos and ambitions of the major public schools, and retaining a classical core of Latin and Greek alongside modern subjects. Discipline was rigorous, however, and the naturally rebellious Hockney was not particularly keen on going there. “David very difficult,” Laura wrote in her diary on 7 September 1948. “Does not want to go to Grammar School.”40 He had no choice.

While David’s first term at Bradford Grammar was spent in the old premises near the parish church on Stott Hill, the following term the whole school was moved to a brand-new building in Keighley Road, Frizinghall, opened on 12 January by the Duke of Edinburgh. Hockney’s class were asked to write an essay on the subject of the opening but, because he had been seated far to the right of the stage, and had to crane his neck to see what was going on, instead of handing in an essay on how splendid the whole occasion was, he wrote about his cricked neck. This was typical of the subversiveness that increasingly epitomised his character, along with a quick wit and an ability to answer back. There were times when he just couldn’t resist going too far. “There was a place in the school called the Long Corridor,” he remembers, “and one afternoon I was walking along the corridor and there was this prefect coming towards me. When he passed me, he didn’t say anything, so I turned round to him and said, ‘Less of your cheek!’ He came straight back to me and I got detention, but I thought, ‘It’s worth it.’ ”41

As a scholarship boy, Hockney was expected to work hard and to do well, which would not have been a problem had he been able to study art. But he soon discovered that in the top form, art was only on the syllabus during the first year, and only for one double period of one and a half hours a week. After that there was no more art until the sixth form, when art appreciation was taught. On the other hand, boys who found themselves in the bottom form doing a general course were allowed to study art. “They thought art was not a serious study,” he recalls, “and I just thought, ‘Well, they’re wrong.’ ”42 Taking a conscious decision to do less work, he spent mathematics classes drawing the cacti on the classroom windowsill, doodled endlessly on all his notebooks, and, during a science exam, left the paper blank save for a line of writing which read “am no good at science, but I can draw,” under which was a sketch of the invigilator.43 In his class, Form 3D, which had thirty pupils, he came thirtieth. This infuriated the headmaster, Mr. Graham, who demanded to know why a scholarship boy like him was so lazy, while his form mistress, Margaret Baker, wrote in her report: “He should realise that ability in and enthusiasm for art alone is not enough to make a career for him.”44

As a result of his tactical idleness Hockney achieved his wish to be relegated to the non-academic level of the bottom division, where he was able to continue in the art class. Here he thrived under the genial art teacher, Reggie Maddox, who encouraged him to get involved in creating posters for the various school societies—particularly enjoyable was dreaming up pictures according to the themes of the Debating Society’s debate. These ended up on the school noticeboard, where everybody saw them, and which Hockney began to regard as his own personal exhibition space. It was, he later wrote, “the first time I had the opportunity to carry out my fantasy about being an artist.”45 That people liked them so much was borne out by the fact that they were invariably stolen.

Hockney was also greatly inspired by his English teacher, Kenneth Grose, who recognised that, in spite of his inability to work hard at anything except drawing, he was full of curiosity. He encouraged him to pursue his love of reading, and made no attempt to stifle his artistic ability. “I remember once when I was supposed to have done some essay for my homework,” Hockney recalls, “and I hadn’t done the essay—instead I’d spent all my time doing a collage self-portrait for the art class—and he said to me in front of the whole class, ‘Hockney, can you read your essay?’ So I said to him, ‘Well, I didn’t do the essay, but I did this,’ and showed him the collage. He said, ‘That’s very good,’ and I was quite knocked over. He was a stimulant and he encouraged me in my ambitions to be an artist.”46

Grose also edited the school magazine, the Bradfordian, and often got Hockney to illustrate articles, usually with drawings done on scraperboard, since they required a high degree of contrast and the school block-makers weren’t very sophisticated. A typical cartoon ridiculed compulsory sports, one of the features of school life that Hockney most hated, showing first a caricature of him standing with a crutch, one foot bandaged up, holding a notice reading “Complaint about compulsory running,” and second one of him being pushed in a wheelchair by an able-bodied runner.

It was becoming clear that art really was the only subject at which Hockney excelled. When he discovered that Bradford School of Art had a junior school attached to it, which took students from the age of fourteen, he pleaded and pleaded with the headmaster to let him go there, until Mr. Graham, seeing that he was never going to give up, finally caved in and wrote to his father: “David’s Form Master and those who teach him have been considering his future, and they think it worth while my writing to you to suggest that as his ability and keenness appear to be on the artistic side he might suitably transfer, before long, to a School of Art, and there prepare himself for a career in some branch of drawing or painting.”47 Kenneth and Laura gave him their full support. But they were reckoning without the forces of traditional education in Bradford.