Sunday Lunch, Hutton Terrace (illustration credit 2.1)

On 25 March 1950, at Eccleshill Methodist Chapel’s anniversary concert, the young David Hockney gave a public demonstration of his skills, sitting on the stage and doing lightning sketches of the performers and of various members of the congregation. Hockney was happy, confident both in the knowledge of his headmaster’s recommendation that he should be allowed to transfer to Bradford School of Art, and in his parents’ support. But his wish to leave grammar school early would turn out to be a pipe dream. “May I suggest that in ‘Reasons for Application,’ ” Mr. Graham had written to Kenneth four days earlier, “that you wish the boy to be withdrawn from the school only if he is admitted to the School of Art.”1 On 5 April after Kenneth had submitted the application, and both he and Laura had gone before the Education Committee at the town hall, the Director of Education himself, Mr. Spalding, wrote back: “After careful consideration the Committee believed that your son’s best interests would be served by completion of his course of general education before specialising in Art. They, therefore, were not prepared to grant your request.”2

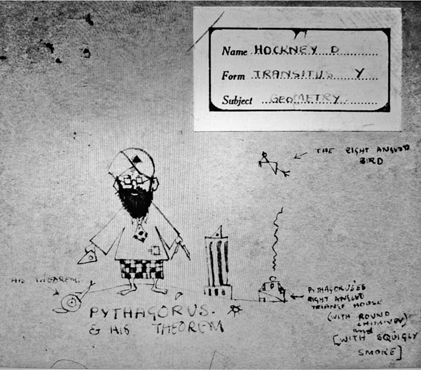

The twelve-year-old Hockney’s disappointment at this blow was deep and bitter. It is something he has never forgotten. He would have liked to go even earlier. “I would have gone to art school at the age of eight,” he says. “You learn a lot when you’re eight. I mean, how old were Rembrandt and Michelangelo when they started art? I don’t think they were much older than twelve.”3 His anger sent his schoolwork into a downward spiral, and he lingered at the bottom of the class. He did virtually no homework, spending most of his time drawing posters for the school societies. “Doing the posters at home,” he later wrote, “did save me from trouble … my mother would say to me, ‘What about your homework? Are you doing it?’ and I’d say, ‘Yes,’ when really I’d be doing a poster. I’d say, ‘This is for the school.’ ”4

Sunday Lunch, Hutton Terrace (illustration credit 2.1)

His form master, Mr. Ashton, was frustrated by his lazy habits and the knowledge that he had real ability. It was as if he couldn’t be bothered. “He still does not really believe,” wrote his loyal supporter, Ken Grose, in his December 1950 English report, “that an artist needs occasionally to use words,” while his report at the end of the Lent term in 1951 was abysmal. His geography was “very lethargic,” “he makes little or no effort with any of his mathematical work,” and even Mr. Grose couldn’t find a good word to say for him, simply writing: “There is no point in his coming to English lessons.” Though he continued to be first in art, even in that subject his teacher reported “little progress,” and the headmaster demanded periodic reports on Hockney during the next term, a sure sign that his future at the school was in doubt. “Is he really silly?” Mr. Graham wrote at the bottom of the December report. “He can’t afford even to pretend to be.”5

The decline in Hockney’s schoolwork did not escape his parents’ notice as he became more and more untidy, his school notebooks increasingly desecrated by doodles. Linking these facts, Laura had the idea of sending him to a neighbour, Mr. Whitehead, a teacher at the Bradford School of Art who gave calligraphy lessons in his spare time. “He obviously thought I was talented,” Hockney recalls, “and people like that, if they find some talented person, will give their lessons for free so my parents didn’t have to pay. I remember he used to chew hard little sticks of Italian liquorice, which made his teeth all black. He was old-fashioned and smoked a pipe, and I used to go to him once a week and be given some exercises to do. He taught me how to use a pen and to make the serif so that the curve was perfect. I liked it because it was teaching me about form, so at least I thought I was learning some skill. He was eager to have a young pupil who was obviously keen and it made the whole business of not being allowed to go to the art school easier to deal with.”6 It was an inspired idea of Laura’s, and Hockney’s schoolwork began to show immediate improvement. “I have been very pleased with his work and his general attitude,” wrote his form master at the end of July, while the headmaster wrote simply: “Most encouraging. His best term so far.”7

“Untitled” (date unknown) (illustration credit 2.2)

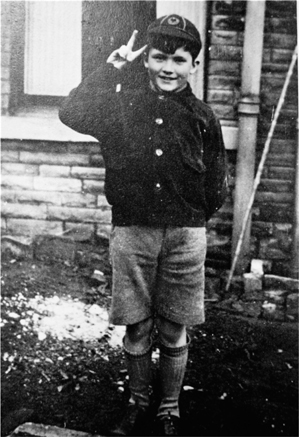

Over the next two years, Hockney managed to keep his head above water, in spite of the fact that his natural desire to clown around often overcame the need to pay attention. He developed a reputation for being funny, and made every effort to live up to it. If this meant tripping over when he came into the classroom, then he would do exactly that. He was an excellent mimic. Nineteen fifty-two was the year of a new radio show that was, the Radio Times announced, “based upon a crazy type of fun evolved by four of our younger laughter-makers.” Their names were Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe, Michael Bentine and Spike Milligan, and the show was called The Goon Show. At a time when almost every family in the country gathered round the radio in the evenings to listen to such programmes, Hockney’s impersonation of Henry Crun, a character played by Peter Sellers, was certain to raise a laugh. A natural anarchist, he would arrive at school without wearing his cap and blazer if he could, which gave him semi-heroic status. “He won the art prize every year,” Laura was to remember, “but at speech days we couldn’t understand the reaction of the other boys when David went up for his award. They stamped their feet, booed, clapped and shouted and made a terrific noise. We spoke to the head about it and he said it was because David was so amusing.”8

“Untitled” (date unknown) (illustration credit 2.3)

At the same time as playing the clown, Hockney was also growing up. When he accompanied Laura every Sunday to Methodist chapel, she may have looked upon him as the perfect son, but there was a lot going on in his life that she didn’t know about, not least his burgeoning sexuality. “There were loads of things I never told my mother,” he remembers. “Actually, I didn’t tell my parents anything that was going on.” One night, for example, he went off on his own to see a film in one of the local fleapits. “I was sitting near the front enjoying the picture when a man sitting next to me suddenly reached over and took my hand and placed it on his erect cock. I remember thinking, ‘I can’t tell my mother about this.’ I enjoyed it and it gave me a lifelong love of cinemas.”9

Sex was simply not discussed in families in the 1950s, and most children found out about it by trial and error, or from dirty jokes and graffiti in public urinals. They learned precious little in school. The novelist Derek Robinson recalled that, at the institution he attended in Bristol, “the two periods of biology scheduled to cover human reproduction left many of us more confused than before. That tangle of plumbing created in chalk on the blackboard; did it really have something to do with our bodies? There was a rumour that sex was supposed to be fun. It didn’t look like fun. The way the biology master described it, it sounded slightly less fun than unclogging a drain with a bent plunger.”10 For Hockney, it was Scout camp that provided the stamping ground for sexual exploration.

He had joined the Cubs at primary school; by the time he went to grammar school he was a member of the Fourth Bradford East Scouts from Eccleshill Church, and celebrated for his very particular participation in the annual gang shows (variety shows at which all the Scouts would sing songs and perform sketches to raise money for local charities) in which, standing onstage with a large easel and a drawing pad, he would do lightning sketches of the Scoutmaster, the vicar and other local people, to great applause. When the group went on camping trips, he would keep the logbook, filling it with drawings and cartoons that depicted their various activities. “David would always make us laugh,” remembers Philip Naylor, a friend of his brother John. “Once at camp he climbed right up into the high branches of a tree and announced that he was the King of the Twigs. Then the branch gave way and he plunged earthwards, and for quite a while after that he was known as ‘Twiggy.’ ”11

“David is off at last with a pack almost as big as himself,” wrote Laura in her diary on 30 December 1952. “… an old Scoutmaster … is allowing the boys to camp in a stable where there is a stove and plenty of coke. They do have good times these days.”12 “When I was in the Boy Scouts,” says Hockney, “I used to be quite naughty, but you’d never talk about it. I mean, you’d put your hand on someone’s cock, but you’d never mention it later. I liked the camping because it was sexy. It was an opportunity to get into someone else’s sleeping bag. We were just kids, teenage boys messing around.”13

Hockney at about ten, in his Cub cap (illustration credit 2.4)

Hockney had a bit of a crush on one of the boys on this trip, David Johnson, who was the captain of the school rugby team. “… they are big pals,” wrote fellow Scout Mike Powell. “… the two Davids found a flooded air-raid shelter and Johnson decided he would dive in and investigate, but he had no swimming kit. It had been raining all week at camp and to minimise the number of soakings we were having, my patrol leader had the idea of making some of us wear swimming trunks. Hockney looked at me and said, ‘Take off your trunks and give them to Johnson.’ I sheepishly did so, quickly slipping into some shorts. David J., school rugby captain, squeezed into my tiny costume and promptly jumped in. The water looked horrible in there and he was soon out, handing back my trunks now stretched to twice the size. The Scoutmaster was so annoyed with the two Davids for being somewhat irresponsible that he ordered them both to take a P B [public bath] in a stream by the camp. They both stripped completely, lay in the stream and the Scouts had to scrub them both with soil-filled turf we had recently dug up during the building of the latrines.”14 On her son’s return from this trip, a week later, on 8 January, Laura noted, “David came home from camp. He has had a fine time and is looking forward to going again. He certainly does get much out of life.”15

The early part of 1953 was clouded for Laura by the sudden death in her sleep of her mother, Mary, on 19 February. “Today seemed strange and empty outwardly,” she wrote the following morning, “—but a strange feeling of calm and quiet within, something I have never experienced before.” The funeral took place on 24 February. “The service at Eastbrook was beautiful—not mournful, but more like an Easter service, as fitted her beautiful life—just called to a Higher service, and quite ready,” and afterwards Laura took Hockney to visit Bradford Regional College of Art. She was armed with a good reference from his headmaster, Mr. Graham, and some of his drawings, and the following Friday she wrote: “I took some of David’s work to the College of Art—and Mr. Rhodes, the Principal, and Mrs. Peters, the head of the Commercial Art department, were very much impressed and assured me that definitely commercial art should be David’s career. We want to give him a chance—but shall have to apply for a grant from the Education department.”16

Hockney sat the all-important GCE exams in July. The papers that have survived give an extraordinary glimpse of a boy sitting in an examination hall, daydreaming and doodling. In his French paper, for example, which required translation of a scene set in a Paris hotel and featuring Madame Noublard, her daughter Jacqueline and the manager, le Gérant, he made no attempt at the work, merely writing, “I’m afraid I know no French but will draw some pictures instead.”17 Caricatures of “Madame Noublard et sa fillette et le Gérant” are drawn at the top of the page; the word “Bluebeard” is mysteriously written at the bottom. Not surprisingly he failed the exam. He did rather better in English literature, which required the design of a stage set for Twelfth Night, and he naturally scored the highest mark for art. He scraped through in most of the other subjects, covering all the exam papers with little sketches.

On his last speech day, when he went to pick up the customary art prize, the whole school gave him a huge cheer. “He has undoubted ability in art,” wrote his form master on his final report, “especially in cartoon and sign-writing work … we have enjoyed his company.” The headmaster bade him best wishes on his new start. “He will be glad to get rid of the figure of fun,” he concluded, “and to establish himself as a sincere and serious person by steady work and merit.”18

Hockney left with a skip in his step only to meet another hurdle—in the previous few months his parents had modified their enthusiasm for his going to art school. This was partly for financial reasons, and partly to be fair to his older siblings, all of whom had left school and gone straight to work. Paul in particular had wanted to be an artist, having got credits in art in his School Certificate, but had failed to find a job in commercial art and had ended up as a clerk in a firm of accountants. Philip had gone to night school to study engineering, and Margaret was training to be a nurse. Encouraged by the views of Mr. Rhodes, the principal of the art college, that their son’s work had commercial potential, Kenneth and Laura now encouraged him to go out and find a job as a commercial artist.

Mr. Graham helped out, arranging an interview with Percy Lund Humphries & Co., a Bradford firm of printers, binders and publishers, and to please his parents Hockney went along with their wishes, putting together a portfolio of lettering and other things he thought commercial artists might do. This included a series of drawings of the various textile processes he had seen—Sorting, Washing, Drying and Carding—on a school visit to the local Airedale Combing Co. He also arranged to take the portfolio round to other studios and advertising agencies in Leeds. Lund Humphries turned him down, saying that he was not suitable for their class of work, while most of the other firms suggested that he return after attending art school. With his heart still set on going there, “I told my parents then,” Hockney remembers, “that it was essential for me to go to art school to get a job. I was determined. I would have cheated and lied and used every trick in the book to get there.”19

Finally convinced, Kenneth and Laura applied for a grant from the Education Committee, and the sum of £35 was awarded, the first instalment of £11 to be paid in November 1953. In the meantime, his rucksack on his back, Hockney set off for a six-week holiday job to earn some money, helping with the harvest on a farm in the East Riding. This was a summer job he had been doing since he was fourteen, a gruelling cycle ride of fifty-four miles to Foxcovert Farm in Huggate, high up on the Yorkshire Wolds. A continuation of the chalk hills of Lincolnshire, the Wolds undulate gently from the River Humber to the coast of the East Riding, occupying an area of about 200,000 acres. Up until the nineteenth century, when they were first cultivated to meet the agricultural needs of the Industrial Revolution, they were little more than a barren wasteland, devoid of trees and vegetation, unvisited by Victorian tourists and largely ignored by artists such as J. M. W. Turner, James Ward and Alexander Cozens, who painted the more romantic grandeur of the West Riding. Yet the summers that Hockney spent working on the land here remain etched in his memory.

“When I first came to the Wolds,” he remembers, “I cycled every-where and I quickly noticed the very beautiful cultivated landscape, so different from West Yorkshire and amazingly unspoiled.”20 There was no farmhouse attached to Foxcovert Farm; the farmer, Mr. Hardy, lived in a house in Huggate. The seasonal workers, all young boys, lodged in outbuildings, the accommodation consisting of a dormitory on the first floor, with three big shared double beds, and a room below for eating and cooking. Across the foal yard was a room known as the “Slum,” which was for recreation and contained a large coke stove, a settle and a dartboard. Each day the boys were out in the fields by seven, helping to bind and stook the corn, and they worked there till seven in the evening, when, exhausted, they would wander down to the local pub, the Huggate Arms. Here the young Hockney, free from parental restraints, tasted his first pint of beer. His mind was never far from home, however. “He once sent us a parcel containing a dead rabbit,” Laura remembered. “The poor postman couldn’t wait to get rid of it. He said, ‘I don’t know what’s in this parcel, but it stinks to high heaven.’ David thought he was sending us a lovely meal!”21

The full-time workers consisted of the foreman, the stockman, a man to look after the horses, and the shepherd, an old man called Tommy Jackson, who never washed and used to chew and spit tobacco. “The thing that struck me,” says Hockney, “was how feudal it all was. The farm labourers all referred to Mr. Hardy as ‘The Master.’ Nobody in Bradford would have called their employer that, not in the mills anyway. It was a terrific experience. The job was boring, but I took home eight pounds at the end and it instilled in me a love of the landscape which I never forgot.”22 After six weeks on the farm he returned to Bradford to prepare for his first term at Bradford College of Art.

Hockney arrived late, his grant having been delayed for two weeks, but his reputation preceded him: his calligraphy tutor, Mr. Whitehead, had told his class that a boy who would soon be joining them could knock spots off the lot of them. Not only that, he cut an intriguingly theatrical figure. After six weeks working in the fields, he was very tanned, in stark contrast to the pale complexions of the other students. He was also eccentrically dressed. Clothes rationing had just come to an end, and he and his father had taken to going to their favourite shop, Sykes Wardrobes, a high-quality second-hand clothes dealer that specialised in acquiring deceased estate wardrobes, including shoes. “You don’t need money for style,” Hockney says. “It’s about an attitude. People dressed pretty conventionally then, but I’d pick up things to make me look a bit different and which I wore out of a sense of mockery.”23 Dave Oxtoby, a painting student who was to become his close friend, remembers sitting with a fellow painter, Norman Stevens, in the life class at the moment when David first came in. “He was wearing a shirt with a high-starched wing collar and a black pinstriped suit with trousers that were far too short. He had on a bowler hat, an incredibly long red scarf, and he was carrying an umbrella. I turned to Norman and I said, ‘Look at this guy, he looks like a Russian peasant. He looks a right Boris.’ ”24 This caused some embarrassment for Hockney, who was already struggling to keep his composure in the face of being confronted with his first ever nude female model. The name stuck, and throughout his time at the college he was always to be known as “Boris.”

Climbing the wide stone steps and entering the pillared portico of the grand old Victorian building that was Bradford College of Art was the achievement of a dream for Hockney. It was all he had thought of for the last three years: to be in an environment where he was going to be learning about nothing except art. “I was interested in everything at first,” he wrote. “I was an innocent little boy of sixteen and I believed everything they told me, everything. If they said ‘You have to study perspective,’ I’d study perspective; if they told me to study anatomy, I’d study anatomy. It was thrilling after being at the Grammar School to be at a school where I knew I would enjoy everything they asked me to do.”25 Mr. Whitehead had told him that quite a lot of students who went to the art school wasted their time there by not doing much work. “I was careful to tell my parents,” he remembers, “that I would not be one of those people, and I did work very hard and quickly noticed all the students who didn’t.”26

The principal of the college in the autumn of 1953 was Fred Coleclough, a bureaucrat who liked every department to be run as though it was the army. So far as he was concerned the business of the college was to turn out commercial artists who would have successful careers in the advertising and printing trades. He had little time for painters, as Hockney was quick to discover. “When I was asked what I wanted to do,” he recalls, “I said that I wanted to be an artist. They didn’t appear to understand what I meant by this, and asked me if I had a private income. They knew I’d been to grammar school and probably thought that I was a bit superior. I said I didn’t know, because the truth is I had absolutely no idea what a private income was. They then told me that if I wanted to do something practical, I would be better off going into the graphics department.”27 Happy at this stage to agree to anything, Hockney lasted just two months in this department, studying commercial art under John Fleming, who supported Coleclough’s views on student training. All the while, however, he had one eye firmly fixed on the painting department.

Once again he approached the principal and asked to be transferred. “They told me that I would have to train to be a teacher, as that was the only living to be got out of painting. I thought to myself that if the only way to get into the painting department was to trick them, then that’s exactly what I would do. So I said, ‘Fine, yes, I really would like to be a teacher.’ ” Agreeing to this meant that so long as he had the required number of GCEs, he could now study painting in order to get a certificate to become a teacher of art. “I sorted this out very quickly,” he says, “because I was a very determined person. I was determined to have a proper art school education, to learn drawing and painting, and I got it, even though it had meant lying to get there.”28

Thus it was that at the beginning of 1954, the sixteen-year-old Hockney joined the painting department of Bradford College of Art. It was tiny, with a core group of five other students: Dave Oxtoby, Norman Stevens, David Fawcett, Rod Taylor and Bernard Woodward. “Dave Oxtoby was a Teddy boy,” Hockney remembers, “who wore a bottle-green suit, so I took one look at him and thought that he was probably one of the ones who didn’t do much work.”29 Because the class was so small, he soon got to know them all well, and his first real friend among them was Norman Stevens. “He came up to me and said, ‘I’ve heard of you. I know you come from the Bradford Grammar School.”30 Stevens’s disability—he had been badly crippled by polio as a child—had given him a determination to succeed at all costs, and this, combined with a wry sense of humour, endeared him to Hockney. They soon became inseparable.

They joked about everything, even Stevens’s limp. One evening, they were out at night in the company of two friends who, along with Hockney, were imitating Norman’s awkward way of walking. Suddenly they saw another genuinely disabled man limping towards them. When they were close enough to him, Hockney said loudly, “All right, Norman, pack it in!” The three friends immediately started walking normally, but of course Norman couldn’t, and as the man passed them he shouted at him, “Cheeky bastard!” This cracked Hockney up.31 The close friendship with Stevens caused a rift at home, in the relationship between Hockney and his younger brother. “I became angry,” John says, “not with David but with Norman, because for the first time ever, David was not mine any more. It was a petty jealousy but I do remember it having a great effect on me. I idolised David. We were buddies, I admired his confidence and openness and we had shared school holidays. We had done so much together. Of course I was the youngest, very immature, and losing him at that time was very difficult.”32 But Hockney was moving ahead, throwing himself into student life, and from now on home and family life were to come second.

Provincial art colleges in the 1950s were for the most part pretty poverty-stricken: drawing from classical casts was still one of the primary modes of instruction, and heraldry was still on the curriculum in many of them. Prime influences were the Euston Road School, formed by William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore and Graham Bell in 1937 to promote naturalism and realism, and Walter Sickert, who had brought the French influence into English art schools. Bradford was little different and the teachers there were struggling to drag it into the modern world. Yet the four-year course that Hockney signed up to, the National Diploma in Design, which was a completely academic training, is now viewed by him as vital to all his later work.

For two years he was to study painting, together with a subsidiary subject, lithography. Then for the last two years, he would concentrate solely on painting and drawing. Two days a week were devoted to life painting, two days to figure composition, again mostly from life, and one day a week to drawing; and during the first two years, one day a week was devoted to either perspective or anatomy. “It meant that for four years,” he later wrote, “all you did was draw and paint, mostly from life.”33

There were two tutors in the painting department whom David found particularly stimulating. Fred Lyle, the senior tutor, was bald, with one eye and a beard, which gave him the appearance of Sinbad the Sailor, but it was the younger of the two who turned out to be the real inspiration. Derek Stafford was twenty-six and a fellow Yorkshireman from Doncaster, though there was no trace of his origins in his accent, as a result of his having attended Stowe School, from where he had been awarded a scholarship to the Royal College of Art. His studies had been interrupted by the war, and in November 1944, with a reasonable knowledge of anatomy from his drawing classes, he was placed in the Royal Army Medical Corps. After eight weeks’ training he ended up in Belgium, just after the Battle of the Bulge, and from there travelled with the medics wherever they went. This included being among the first people into the concentration camp at Belsen, a horrific experience for the eighteen-year-old boy. “For years I never spoke about it to anybody,” he says, “and I still sometimes wake up at night with the smell of it in my nose.”34

Stafford took up his place at the Royal College in 1948, one of a generation of artists cut off from the mainstream of modern art by the experience of war at the crucial stage of their developing careers. The government actively encouraged them to take a patriotic approach to their art, and engage with the English landscape and its monuments, the result being the rebirth of a British Romantic movement. Leading lights among these self-styled neo-Romantics included John Minton, Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun, Keith Vaughan, Eric Ravilious and John Craxton, who were simultaneously forward-thinking and aware of their debt to nineteenth-century artists such as Samuel Palmer and William Blake. Some found a further outlet for their work in another patriotic project, “Recording Britain,” the brainchild of Sir Kenneth Clark, which commissioned artists to paint watercolours that would celebrate the country’s natural beauty and architectural heritage. The nostalgic feel to much British painting in the 1940s was exemplified in the work of artists such as John Piper, Edward Bawden, Kenneth Rowntree and Stanley Spencer.

By the early 1950s, this veneration of the Englishness of English life was being eroded by a new movement celebrating, in the words of one of its leading exponents, the young painter John Bratby, “the colour and mood of ration books, the general feeling of sackcloth and ashes.” “The painting of my decade,” he commented, “was an expression of its Zeitgeist—introvert, grim, khaki in colour, opposed to prettiness, and dedicated to portraying a stark, raw, ugly reality. The word angst prevailed in art talk.”35 In December 1954, in the journal Encounter, the art critic David Sylvester gave the name to this movement which, he wrote, “takes us back from the studio to the kitchen” and featured paintings which included “Everything but the kitchen sink? The kitchen sink too.”36 The Kitchen-Sink movement, which reached its zenith in 1956 when its main practitioners—John Bratby, Derrick Greaves, Edward Middleditch and Jack Smith—represented Britain at the Venice Biennale, echoed the strength of social realism in art at the time, and this was reflected in the work Hockney saw from his tutors, mostly gritty Bradford street scenes in muted colours.

Derek Stafford had joined the staff of Bradford College of Art in 1953, the year before Hockney arrived, fighting off eighty other applicants after a “soul-destroying” year working in a furniture store in Doncaster. He had very quickly found a house and studio only four minutes away from the college. “When I started the job,” he remembers, “I was determined to teach the students my way and not anybody else’s way, and my way was to teach them to think. Drawing is a cerebral process. It is not just imitating what you see, it is understanding what you see. That is what I wanted to put over.”37

From the beginning he fell out constantly with the bureaucratic Fred Coleclough. “I was trying to encourage thinking,” says Stafford, “and getting the students to do things their way, to come into a life class full of energy, to sit down, to examine, to walk up to the model to look, to walk round the model, to see what was taking place outside of their vision, to make them realise that the edge is only the last part you see before it moves out of your vision. This excited them.”38 In his life class, the students would start drawing as soon as they came in, for about half an hour. Then the model would take a rest and Stafford would look at the work individually, sometimes making a comment, sometimes just sitting with them and making them watch him draw. “What I was quick to notice,” Hockney recalls, “was that the teachers were seeing more than I was seeing. I hadn’t looked hard enough, and I quickly saw that, and so I began to look harder myself. And if you are strict with yourself, after a few weeks you begin to get better and better.”39

To begin with, Hockney didn’t show himself as any more or less talented than the other students. What he was good at was drawing Desperate Dan from the Dandy, playing the fool, joking and disrupting the class. “He’d be throwing rubbers about in life drawing,” Stafford remembers, “and then before you got to him he’d turn his life drawing upside down so you’d have to strain your neck to look at it. I had to take him aside and tell him, ‘David, you’ve got to take this seriously.’ He soon showed himself to be the most industrious of students. He was tenacious in his approach and would always stay late, and if we weren’t talking during the lunch hour, then he’d be drawing.”40

Because most of the group’s understanding of art was limited to what they’d seen in newspapers or comic books, Stafford encouraged them to scrimp and save up to travel occasionally to London. David made his first trip on 26 February 1954. “We went to the National Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum and the Tate Gallery, all the obvious places, simply because I’d never been to London before.”41 John Loker, a student who arrived at the college in 1955, recalls how they used to leave school on a Friday night, get themselves down to the Great North Road, the A1, and then hitchhike. When they arrived, in the early hours of the morning, they would buy a ticket on the Circle Line and then sleep on the train until the time the galleries began to open, at which point they would trudge round as many exhibitions as they could fit in.

“The amazing thing is,” says John, “that we would do these trips with virtually no money—we might have half a crown to last us the whole trip. We used to go to the Lyons Corner House café just off Trafalgar Square where they used to have a salad counter at which you could eat as much as you could fit on the plate. We used to get a plate and pile it up so high you had to hold both the top and the bottom of the plate to keep the salad from falling off. We’d stuff all this down us and very little else.” Hitchhiking back on Saturday nights, there were very few cars on the road, mostly just lorries, and they often ended up sleeping in a barn in the middle of nowhere, finally getting home on the Sunday evening. “It was a great thing to do and we always used to have a lot of fun doing silly studenty things. I remember one time in the Tate Gallery Norman Stevens fell asleep on one of the benches, and David took out a page from one of his notebooks, wrote ‘DO NOT DISTURB’ on it in block capitals and propped it up on him, and we just left him there.”42

Derek Stafford considered these trips a vital part of the students’ education. “I encouraged them to go to the National Gallery and look first at the old masters, and then go and look at the new masters, and they would see there was an evolution from one to the other, each demonstrating in their own way something of their own period. That is what they were going to be doing whether they liked it or not. I told them that they could not live outside their own period. I told them that the influences upon them were going to be the influences that were there just before them, and that they should not ignore them. If they rejected what was new, then they were going to become bad artists. They had to look, they had to absorb, and then evolution would take place which is a natural process of life.”43

It was on one of these trips to London that David first saw the work of Picasso, an artist about whom a high degree of philistinism prevailed. This ranged from Sir Alfred Munnings’s comment at a Royal Academy dinner that Picasso deserved to be kicked down the steps of Burlington House to the student at Bradford College nicknamed “Picasso,” because he couldn’t draw. “I was horrified,” says David, “because I knew that Picasso drew beautifully and I just thought to myself, ‘They haven’t been looking at Picasso properly.’ Well, I had, and I thought that whatever you didn’t know about abstraction, you should know that Picasso had done some marvellous paintings. I remember being very struck by Picasso’s painting of the Massacre in Korea which he painted in 1951 and which I saw when I was still at Bradford Grammar School. It was reproduced in all the newspapers and I remember at the time how it was dismissed as being nothing but communist propaganda. I thought to myself that whatever they said, Picasso was better than that.”44

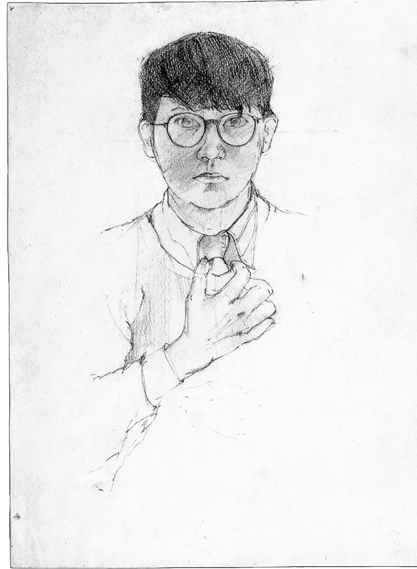

That Hockney absorbed Stafford’s advice is clearly shown in some of his best early work, a series of self-portraits he painted at home. He did a fair amount of work at Hutton Terrace, which was far too small for a studio. “Our front bedroom is in a terrible state,” wrote Laura on 5 April. “What it is to have an artist son!! David thought he should be allowed to use the little bedroom for a studio (just decorated and all) but I positively refused. I need the room, and if David had it he would ruin it. We all appreciate his work, but he is getting to expect all and give nothing in return—his own room was dreadfully untidy. We compromised and as our front bedroom has to be decorated, I said David could finish his portrait in there. He is doing a full-length portrait of himself and has the wardrobe mirror dismantled and propped up where he can see it—a table littered with paints—brushes—etc—but he dropped paint on the carpet just where he hadn’t covered it with newspapers. Kenneth thinks I should let David use the little room, but I still think he should respect other people’s work as well as his own. He is a happy go lucky fellow, a real anarchist—but it just won’t do.”45

Self Portrait, 1954 (illustration credit 2.5)

The portrait Laura was referring to is one of three self-portraits Hockney painted in 1954, the earliest of which shows him three-quarters on, staring intensely into a mirror with a look of both concentration and hesitancy on his face, his hair flopping against his forehead, and a background of the rooftops of Hutton Terrace. It is a remarkably assured portrait of a young man on the threshold of life, a little shy and a little uncertain. While this painting owes much to the traditional academic approach of the Euston Road School, the next self-portrait, painted against a backdrop of newspaper clippings and boldly using blocks of colour to depict his distinctive clothes—a bright yellow tie and long red scarf—takes a much more modern approach. Finally, the third picture—a striking lithograph in five colours, in which he is seated in a chair before a background of yellow wallpaper, the black and white lines in his pudding-basin haircut echoing the stripes of his tie and trousers—is, to quote Mark Glazebrook, “positively prophetic in its fluent line, its bright colour, its technical experimentation and in its direct, confident, quirky self-presentation.”46 Here was the evolution at work that Derek Stafford felt was so important.

By the end of 1954 Hockney was living and breathing the life of an art student, and showing the determination and devotion to work that would characterise his life. “He had this overriding passion for his work and nothing else,” Dave Oxtoby remembers, “and that was a tremendous influence on everybody.”47 Through him they suddenly saw that painting was the centre of their world, and it bound them together closely as a group. “I loved it all,” wrote Hockney, “and I used to spend twelve hours a day in the art school. There were classes from nine-thirty to twelve-thirty, from two to four-thirty; and from five to seven. Then there were night classes from seven to nine, for older people coming in from the outside. If you were a full-time student, you could stay for those as well; they always had a model, so I just stayed and drew all the time right through to nine o’clock.”48

But Hockney also threw himself into the extracurricular activities of the painting department, though he was never without a sketch pad. There were card games in the common room during the lunch hour, where he was likely to be discussing with Stafford subjects varying from vegetarianism and the perils of smoking to the theory of art. In the evenings they would go down to one of several pubs to play darts, sessions that would invariably end up with Hockney singing his favourite song, “Bye Bye Blackbird,” at the piano, or bringing the house down by pulling his face so that he looked exactly like Orson Welles. The games of darts eventually led to them forming a darts team to take on Leeds School of Art at a pub near Leeds Town Hall. During one of these visits, Hockney was introduced to an elderly artist, Jacob Kramer, a former Vorticist and associate of Wyndham Lewis and William Roberts, who had enjoyed a measure of fame in the 1920s but had since fallen on hard times. Often mistaken for a tramp by those who didn’t know of his distinguished past, he was reduced to propping up the bar and telling stories in return for drinks. Nevertheless, he made a powerful impression on the young Hockney. “I had seen some of his work because he had two or three paintings in Leeds City Art Gallery. He had lived and worked in Paris and was living proof to me that it was possible to make a living as an artist. And I thought to myself, ‘This is a real artist, not just a teacher. He may have met Picasso or Braque or any of those people. He’s a real link with bohemian Paris.’ I was a bold little kid and I thought this was really exciting.”49

While Dave Oxtoby, Norman Stevens and John Loker had a skiffle group and played at the occasional college dance—Oxtoby on tea-chest bass, Loker on washboard and Stevens on vocals, alongside three guitarists and a banjo player—skiffle was of little interest to Hockney. He only loved classical music, which he used to play very loudly at home. “When we used to go to the Hockneys’ house,” Philip Naylor remembers, “the lounge was really tiny and David used to like to tuck himself away in there and listen to his music. One day he decided that we were uncultured little oiks, and made us sit in there and he played us his Mozart records on the Deutsche Grammophon label and conducted for us using a pencil as a baton.”50 At weekends, Hockney would go down to St. George’s Hall, where he had secured himself and his fellow students jobs selling programmes in return for free seats to hear the world-renowned resident orchestra, the Hallé, conducted by Sir John Barbirolli. “I had my free seat all the way through my time at college,” he recalls, “and I would just sit and listen and draw. It was lovely.” Pages of drawings in his sketchbooks reflect this, annotated with titles such as “Second Bassoon, Hallé, Saturday 29th,” “Beethoven’s Symphoney [sic] No. 1” and “Listening to Sibelius.” He also designed the occasional poster to advertise a concert.

Even in the hallowed atmosphere of St. George’s Hall, Hockney still developed a reputation for being a “character.” Philip Naylor remembers that “David would somehow always contrive to be late, arriving after the orchestra and sometimes even after the conductor. The audience used to cheer and applaud him because, even if they didn’t know him, he was a feature of the town.”51

The friends also used to regularly convene for parties at Derek Stafford’s new studio in Manningham Lane, just off the main road to Saltaire. Stafford was only ten years older than his students, but they were in awe of his sophistication. “It was like a bolt from the blue, somebody like that turning up at Bradford College,” Dave Oxtoby recalls. “His whole attitude was refined.”52 They discussed the theory of art, and the latest exhibitions, and he introduced them to cheap French wine, which was much harder to come by in those days, and which none of them had ever tasted. “They used to go down and vomit in my bath,” Stafford remembers, “and I would have to clear up the mess the next day, but they were great evenings and we all got on like a house on fire.”53

Occasionally they discussed politics, more likely than not prompted by Hockney’s father sounding off on one of his favourite rants. The figure of Kenneth Hockney preaching anti-war and anti-nuclear sermons from his soapbox was a familiar one in Bradford, particularly in Foster Square, and he got his son and his friends involved in helping with propaganda. Rod Taylor, a textile student, had a cellar with a screen-printing machine which he lent them to print posters. “I once saw David and Kenneth,” Mike Powell, a boyhood friend, remembers, “standing in Bradford’s Town Hall Square during a rag-day parade carrying large placards. David’s read “CHARITY IS HUMBUG IN A WELFARE STATE,” while Kenneth’s read “STOP THE WAR—CHRISTIANS SHOULD NOT BOMB CHILDREN.” Such were David’s leanings at that time. I saw him occasionally sporting a full khaki ‘Castro-style’ combat outfit complete with forage cap and red star, incongruously sitting on the top deck of the Eccleshill trolley bus. He quickly got the nickname ‘Boris’ in the village, Ken being referred to as Commissar Ken after placing the Daily Worker for sale at the local newsagent’s at his own cost.”54 But though Hockney supported his father’s anti-war views and those on nuclear disarmament, he couldn’t go along with his communist sympathies. “I was much more of an anarchist,” he says. “My father had a very rosy view of communism, but of course he’d never been to Russia. He was rather like Mr. Kite in the film I’m All Right Jack who, when Mr. Windrush asks him if he’s ever been to Russia, says, ‘Ah, Russia, all them cornfields and ballet in the evenings.’ That’s what my father thought.”55

With the exception of Hockney, most of the boys had girlfriends, or were looking for girlfriends, and the group tried to set him up with a very pretty girl called Terri MacBride who was a regular at Derek Stafford’s parties. He showed little interest beyond taking her out on the occasional trip to the cinema, which his friends interpreted as being because his passion for his work overrode any interest he might have in sexual activity. It never occurred to any of them that he might be gay. “I probably always knew I was gay,” says Hockney. “I certainly wasn’t interested in girls, and I didn’t really have to pretend to be because there wasn’t much social pressure. I remember that when Paul got engaged, I thought, ‘That’s not for me,’ and I must have known then that I would never marry. If anyone had asked me if I was gay, I would just have got out of it. I didn’t really feel that normal anyway, because I’d begun to realise that my talent made me different.”56

On Christmas Eve 1954, Laura wrote in her diary: “Dad posed for David most of the afternoon.” This was the start of Hockney’s first serious portrait in oils, a painting of his father, which took just under a month to complete. It was painted on an old canvas Kenneth had bought at a jumble sale, so Hockney had to paint over whatever was on it. His father was not an easy subject as he was incapable of sitting still, his insatiable curiosity always getting the better of him and causing him to question and comment on everything that was going on. Since he’d paid for the canvas and bought the easel, he felt he had the right to do this. “My father,” wrote Hockney, “… set the chair up for himself, and he set mirrors around so he could watch the progress of the painting and give a commentary. And he would say ‘Ooh, that’s too muddy, is that for my cheek? No, no, no, it’s not that colour’…and I’d say ‘Oh no, you’re wrong, this is how you have to do it, this is how they paint at the art school, and I carried on.’ ”57 Portrait of My Father is a touching and sensitive work, over which the ghost of Walter Sickert lingers, beautifully executed, painted in muted tones, his father seated in a chair, hands clasped and looking almost sheepishly at the floor.

Hockney worked on the painting at home, mostly on Saturday afternoons when Kenneth had finished work, creating further chaos in the house and upsetting the orderly life of his brother John, who had just started working for Montague Burton, the tailors. “The sharing became difficult when David began painting in the attic,” wrote John. “He was very untidy. Clothes dropped where he got out of them, sometimes hiding a tube of paint which, when accidentally stood on, squelched over whatever had been lying there. This became the topic of typical brotherly arguments, David’s total lack of any consideration except for his painting and my own growing ego about having to look smart. The two opposed. It was never bitter, frustrating perhaps, but Mum and Dad were great moderators. It must have been very difficult for David whose world then was purely focused on painting and drawing, and mine thinking looking good was important.”58

Portrait of My Father was finished towards the end of January 1955, and submitted, along with a small landscape of Hutton Terrace, to Leeds Art Gallery for their biannual Yorkshire Artists Exhibition. This was a prestigious event to which all the staff of the art college sent work, along with teachers from other local art schools. Much to David’s surprise, both pictures were accepted, though he didn’t bother to put a price tag on them as he thought no one would buy them. The exhibition opened on Saturday, 29 January. “Kitchen upset all morning,” Laura wrote that day, “—David sketching in it. He went off soon after lunch for the opening of the Exhibition at Leeds … Ken and I went. We were proud of David’s pictures; they looked quite at home amongst the others.”59 After his parents had gone home, David was approached by a man called Bernard Gillinson, a friend of Fred Lyle’s, who offered him £10 for the portrait, a considerable sum then. After checking with Kenneth that he was happy for the painting to be sold, Hockney accepted the offer and called Laura to tell her. “He rang me up and said, ‘Hello, Mum. I’ve sold my Dad.’ It was so funny the way he said it. He got £10, which was a fortune to him at the time. He was so proud.”60 It was his first sale and to celebrate he took all his friends to the pub. “That probably cost a pound,” he later wrote. “The idea of spending a whole pound in a pub seemed absurd, but with the rest of the ten pounds I got some more canvases and painted some more pictures.”61

After passing the Ministry of Education intermediate exam at the end of 1955, Hockney decided to apply for a place at the Royal College of Art in London, a decision in which he was greatly influenced by Derek Stafford, who believed him to be the most talented student he had ever taught. But he had his own reasons too. “I knew that it would take me out of Bradford, and I wanted to leave Bradford because I scarcely knew of an artist who lived in Bradford.”62 So he devoted his last two summers there, 1956 and 1957, to preparing himself for this important step. He converted one of his father’s prams into a mobile art studio—an idea borrowed from Stanley Spencer, of whom he was a great admirer, aping his appearance, right down to the National Health glasses, fringed haircut and ubiquitous umbrella—and loaded into it all his oils and watercolours, brushes and pencils, his sketchbooks and canvases and his easel, to transport them around Bradford to paint. “I had become quite interested in Stanley Spencer,” he wrote. “… I knew he was regarded as a rather eccentric artist out of the main class of art both by the academics who favoured Sickert and Degas, and by the abstractionists who dismissed him.”63 When Hockney’s brother Paul was doing his national service in 1956, stationed quite close to Spencer’s home in Cookham, Hockney asked him if he would go and ask for the painter’s autograph. So one evening in the early summer Paul set off on the bus from Maidenhead to Cookham, where he was directed by a passer-by to Spencer’s house.

“I knocked on the door,” Paul recalls, “and it was soon answered by this little man wearing round rimless spectacles. He identified himself as Mr. Spencer and I told him that my brother was an admirer of his. He asked me to come in. The house wasn’t scruffy exactly, but there was junk all over the place, piles of papers and books and all sorts of things. I remember there were loads of mugs everywhere with the remains of tea in them, and plates with bits of bun and biscuit on them. He was wearing a little pullover with holes in it and paint all over it. He said, ‘You don’t mind if I carry on with my painting?’ On the wall he had this massive canvas. It was Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta and I remember thinking what a peculiar hat Christ was wearing. It was half finished, and he had these two stepladders and would go up one and put on a little paint and then come down and take a look, and then put some more on. He didn’t say much. Eventually he signed the book I’d brought and I left.”64

Hockney soon became a familiar sight in Bradford, pushing the pram around the city looking for suitable subjects. He painted, among other subjects, street scenes, the interiors of shops, people sitting about in a launderette, a fish and chip shop, and his family sitting down to Sunday lunch in their best suits. “He was the first person I ever saw,” says Derek Stafford, “who painted semi-detached houses. But he took them on and he did remarkably interesting things with them. His subjects were carefully observed. He looked at his own environment and said, ‘This big city I live in may be grey and black, a dirty city, but there is a magic in it if I look at it closely,’ ”65 while Dave Oxtoby recalls, “There was a solidity, a weight, to David’s work at that time. Even his little drawings were very heavy, in particular some pictures of pubs on corners and things like that which were really solid. I remember also he did a painting once of the tram wires and the trees, and the break-up of the trees. He actually painted in between the branches with different colours, slightly different blues so that the branches would disappear and the difference in the blues carried the line of the branch as it went through. I thought the way he handled his paint then was really amazing. He was constantly trying new things.”66

He experimented with colour and developed his own technique for doing his outdoor paintings. He found an unusual colour which he called “Indian yellow,” a synthetic dye that he would wash all over his board and work on while it was still wet, so that the underlying Indian yellow influenced every colour he painted into it. “It created a kind of homogeneous sensation over the landscape he was painting,” says Stafford. “It did work for him and he created some very interesting landscapes.”67

The only restriction was the cost of paint, which was prohibitively high for all the students. When Hockney went to an exhibition of van Gogh at the Manchester City Art Gallery in 1956, what struck him most was how rich the artist must have been, to use a whole tube of blue to paint the sky, something that not even one of Hockney’s teachers could afford. He found novel ways of raising funds to buy paint, which also enhanced his reputation for being an eccentric. These included taking money in return for dares. “We’d go painting round the canal,” Dave Oxtoby remembers, “and come the end of the day David would say, ‘Give me sixpence and I’ll jump in the canal,’ and he’d jump in just to get some money.”68

Depending on how many people were involved, the dares could prove quite lucrative. “David was painting with other students near the canal at Apperley Bridge,” Laura wrote in her diary one day. “During lunch hour they dared him to walk the edge of the Spring Bridge—he did it, but fell in at the end and came home dripping wet—but just in time for the last lot in the washer. He earned 10 shillings with his daring.”69

At the beginning of 1957, Hockney took the Royal College of Art entrance exam and passed with flying colours. “Mr. Coleclough wishes me to convey to you his congratulations,” wrote his deputy. “He is delighted with your success.”70 Then, at the end of the summer term, he sat for the National Diploma in Design. For this he spent a week making a painting of a nude model, and he showed some of the pictures he had made of Eccleshill and its surroundings. The examiners were impressed enough to award him a first-class diploma with honours, and his painting, Nude, was picked for a travelling exhibition of art students’ work. He now waited anxiously for further word from the Royal College, which had required successful applicants to submit a portfolio of drawings, watercolours, lithographs, etc., along with a number of actual paintings. Hockney had sent life drawings, life paintings and figure compositions, and paintings he’d done at the art school and at home during the holidays. Just in case he failed the interview, he had also sent similar work to the Slade School. He was told there were three hundred people applying for the Royal College and thirty places available. He successfully passed the first hurdle, and was selected for interview.

The interview process took two days, so students from the provinces had to stay at least one night in London. Applicants would spend the first day in the Life Room drawing a nude model, and on the second day would show these drawings, along with all the other work they had submitted, to the college professors. “I naturally thought I wouldn’t have much of a chance,” Hockney recalls, “because all the London people would be much better than me. You had to do a life drawing as part of the interview and I remember going round looking at the other people’s drawings and thinking to myself, ‘Well, I can do just as well as that. Maybe I will be OK.’ ”71

At the end of the first day Hockney and Norman Stevens, who had also been selected, returned to the bed and breakfast off the Earls Court Road the college had recommended. In the hall they ran into Derek Boshier, a graduate student from Yeovil College of Art in Somerset and a fellow applicant. “I recognised David straight away from having seen him in the Life Room,” Boshier remembers, “because of his straight jet-black hair and the tweed suit he was wearing. He told me he had his interview the next day, and asked me rather sheepishly in his broad Yorkshire accent, ‘Do you think we’ll get in?’ ”72 Boshier had planned to cruise the streets of Earls Court looking for nightlife, but ended up going up to Hockney and Stevens’s room to discuss the interview and help them drink their way through the crate of Guinness they had bought. The following morning, a little woolly-headed, they walked back to the college buildings in Queen’s Gate to face the selection panel. “You had to lay out all your work on a table,” Hockney recalls, “which consisted of about six paintings, lots of drawings, including the life drawings of a nude, in front of a panel of old people. Actually it was very exciting.”73 The “old people” were the college professors: Carel Weight, the head of the painting department, who took centre stage, with Ruskin Spear, Roger de Grey, Colin Hayes, Ceri Richards and Rodney Burn, all distinguished artists, on either side of him. What Hockney did not know, and which was very much in his favour, was that Carel Weight was becoming increasingly disillusioned by the number of his students, such as Dick Smith and Robin Denny, who were turning to the abstract. He was deliberately looking for young artists who showed the figurative in their work. On the strength of what he saw, Weight decided to offer Hockney a place on the postgraduate course in painting.

Hockney was also offered a place at the Slade, but his heart was set on the Royal College, whose offer he happily accepted.