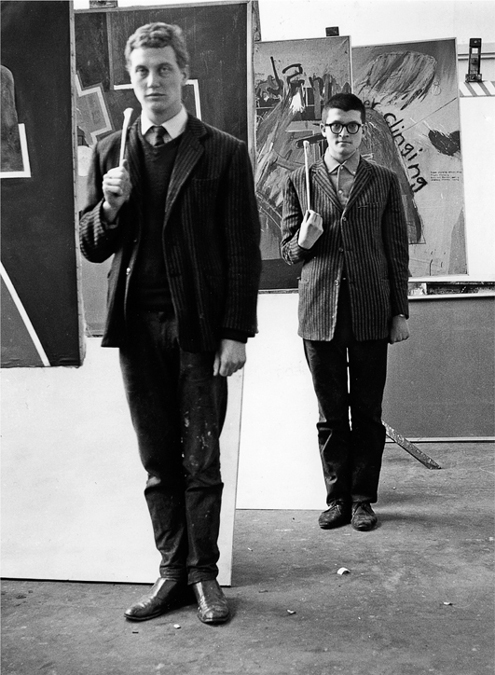

David Hockney and John Loker (illustration credit 3.1)

David Hockney and John Loker (illustration credit 3.1)

“Before university … there was national service to be got through,” says Alan Bennett in his memoir, Writing Home, “regarded at best as a bore, but for me, as a late developer, a long-dreaded ordeal.”1 Just as this compulsory military service, reintroduced in 1947, delayed Bennett’s going up to Oxford for two years, so it delayed David Hockney’s arrival at the Royal College of Art till September 1959. Like his father, Hockney registered as a conscientious objector, at a point when the authorities were taking a more relaxed view of ethical objectors. Hockney was told he would be called for interview in September 1957, and assigned suitable work in the community. But first there was a long summer of painting to enjoy.

In Hockney’s last year at Bradford, he and John Loker decided to enter an annual competition, the David Murray Landscape Scholarship, named after the famous Scottish landscape painter. The prize was £48, and they made a deal that if one of them won it, they would share the prize money and go off painting together for the whole summer. Loker also agreed to put into the pot any winnings from his lunch-hour card games. Luck was with both of them: Hockney won the scholarship and Loker won at cards. With their mutual love of Constable, they settled on Suffolk as the best place to paint, and placed advertisements for accommodation in the local papers. Being young and impatient, however, they decided that they couldn’t waste time sitting around waiting for the replies to come in, but would head straight off for St. Ives in Cornwall, the centre of the thriving colony of artists headed by Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth.

They packed their paints for the journey in a large trunk. “What we used to do,” John Loker remembers, “was buy a half-hundredweight tin of white lead paint. Then we used to buy small tins or big tubes of titanium white and mix the two together for our white paint. We also bought lots and lots of tubes of different-coloured oil paints. We needed an easel, so we smuggled one out of Bradford College and took it with us.”2 When they set off for the south-west from Paddington station, the trunk, which they struggled to carry, went on the scales and weighed in at two hundredweight. Eventually they managed to get all their stuff on the train and set off for Cornwall.

Penniless as they were, the best accommodation they could come up with on arrival was some way out of St. Ives, up a steep hill on the road to Zennor, where a farmer gave them the use of a derelict barn in return for their cleaning it out. “It was chicken droppings on chicken droppings on chicken droppings,”3 says Loker. They spent hours scrubbing it and putting disinfectant down, and finally laid their sleeping bags on the stone floor with every intention of staying there for some time. The following morning, they borrowed a wheelbarrow from the farmer and went down to the station in St. Ives to fetch the trunk, which they then had to push up the hill. While Loker organised setting up the barn into some kind of studio, Hockney went off to the post office in St. Austell, to which they had arranged for their mail to be sent. Events had moved quickly: he returned with a cheque for £24, the first half-payment of the landscape prize, and a letter offering them a cottage in the Suffolk village of Kirton for £3 a week.

“The upshot was that we decided to go to Suffolk there and then,” Loker recalls. “The only problem was we were unable to cash the cheque anywhere because we didn’t have a bank account, so we decided that the best course to take was to go and see Barbara Hepworth, who we knew was rich and who lived nearby. Arrogant as we were, we just turned up on her doorstep, knocked on the door and asked if she could cash a cheque for us. She was very friendly, and organised to have it cashed by the Newlyn Art Society. As it turned out, we didn’t do any painting in Cornwall. All we did was clean out someone’s barn for them. We took the trunk to the station, returned the barrow to the farmer and set off on the train that night.”4

The journey to Suffolk was long and tortuous, involving going through London and changing trains, but when they finally arrived they were delighted with their accommodation: an old horseman’s cottage in the grounds of a much larger house, with an outside lavatory and no bathroom. Their landlords, John and Margaret Burton, lent them bicycles and they became familiar figures cycling around the local countryside looking for suitable views to paint or draw. They worked happily like this for a few weeks, Hockney painting small landscapes, few of which have survived, and Loker slightly larger ones, until they ran out of money, before the second half of the prize money was due. After three days without food, Loker, driven by desperation, went scavenging in the fields and came back with what he thought were some turnips. He scrounged some Oxo cubes from the Burtons’ maid, and boiled up what turned out to be not turnips but sugar beet, which made an inedibly sweet mush.

“It was then that I got a clear notion about life,” says Hockney. “We were on the point of starving, so I rang up my parents, reversing the charges as you could in those days, and I explained to them that we had absolutely nothing, and by that I mean not even threepence. I told them that the second cheque for £24 would be arriving in a few days and could they possibly send something for us. The next day I received a postal order for two and sixpence. When I opened it I spent two shillings of it on a packet of cigarettes, but at that moment I thought to myself, ‘From now on, you’re on your own, David.’ What I didn’t realise at the time was that, aged twenty, that was a very, very useful thing to know. I suddenly felt freer, that I’d finally escaped the family.”5

By this time Hockney and Loker had fallen somewhat out of favour with their landlords who, their novelty value having worn off, now saw them not as tame young artists, but rather as scruffy students who kept an untidy house and cleaned their paintbrushes on their trousers. But in the long hours of painting and cycling around the county, they had made other friends, two of whom, Ken Cuthbert, a local artist, and his friend Denis Taplin, a future gallery owner, invited them to exhibit at the Felixstowe Amateur Arts Show.

“We were a bit arrogant at first,” Loker recalls, “thinking we didn’t really want to show our work in that kind of environment, but we were short of money and he said they would put some screens up and we could have our own exclusive corner, so we decided to do it.”6 The evening of the private view got off to a bad start when Hockney’s cycle light fell off into the front wheel, catapulting him straight over the handlebars and writing off the bike, an incident unlikely to further endear them to their landlords. But when they eventually limped into the show, they were overwhelmed with people rushing up to greet them and demanding to know the prices of their work. “We were selling drawings for two and sixpence, next to nothing really,” Loker remembers. “I even sold a five-foot painting for six or seven pounds. But it was a fortune in those days and we were suddenly rich. We’d made about equivalent to half the value of the scholarship and that meant that we didn’t have to go home. The paintings were mostly landscapes but they were landscapes in which we were trying to do something slightly different. The workings of the paintings were all there to see. They were serious pictures for us. The way we painted was the way Derek Stafford had taught us, which was that unless we were totally committed to our work there was no point in painting at all. And we were willing committers.”7

At the end of this idyllic summer, Loker returned to Bradford College of Art and Hockney reported to the Ministry of Labour and National Service in Leeds to be assigned employment. His first job was as a medical orderly in the skin diseases ward of St. Luke’s Hospital, Bradford. He lived at home and worked long hours at the hospital, a salutary experience. His jobs included putting ointment on the patients, one of whom, a pot-bellied old man whom he particularly loathed, had to be regularly dabbed with calamine lotion. The old man took pleasure in standing stark naked in front of the shy young orderly and reminding him, “Don’t forget the testicles, David.”8 “I swept the floors, put the ointment on, and was the caller in the afternoon bingo games. If the TV broke down, or if you didn’t give them anything to do, they just sat and scratched. I was also the runner. I used to collect all their bets, mostly sixpences and shillings, and take them to a porter who took them to a bookie. I soon knew which patients won regularly, so I backed the same horses and won too.”9 There was no time for painting and Hockney used to scrub the floors singing, “Roll on September 1959!” The one pastime he did indulge in was reading. Even though he’d never been abroad, he decided to take the time to read Proust, because he’d been told that À la recherche du temps perdu was one of the greatest works of art of the twentieth century. He struggled through it, feeling that he wasn’t sure he was getting that much out of it. “I remember that asparagus was mentioned in it,” he says, “but I didn’t even know what an asparagus was.”10

Living at home, Hockney was at close proximity to his father’s increasingly vociferous political views, which had made him a celebrated figure in Bradford. Kenneth left copies of Peace News on Bradford’s buses or on benches in the city parks, and he hired billboards and painted slogans on them in bright colours—BAN THE BOMB or BAN SMOKING or END HANGING NOW—adding fairy-lights during the Christmas period. He worked so hard for Sidney Silverman’s anti-hanging bill that when it was finally passed in June 1956, he was invited down to the House of Commons for the final vote.

None of this carried much weight with Laura, who felt her husband’s role should be supporting the family, not squandering money on such causes. Audrey Raistrick, a fellow Bradfordian and a founder member of CND (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), remembered going round to the house in Eccleshill one winter morning to collect some goods promised by Kenneth for the Daily Worker Bazaar. It was a cold and snowy day and Laura was busy shovelling snow off the front steps. “I greeted her warmly,” she recalled, “and asked if Mr. Hockney was in. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘He’s out doing good!’ ”11

Kenneth’s political campaigning also took the form of enthusiastic letter writing, usually several a day and often using pseudonyms, such as K. Aitch, K. Kenlaw, and the Russian-sounding K. Yenkcoh, which was simply Hockney reversed. He wrote not only to newspaper editors and publishers, but to politicians and world leaders such as Nasser, Stalin and Mao Tse-tung. He encouraged his children and their friends to question everything. “He taught us a lesson,” John Hockney remembers. “He purchased the Soviet Weekly, China News, The Times, Manchester Guardian, Daily Express and Daily Mail, Peace News and the Daily Worker. He then asked Margaret, David and me to read about a particular incident that was reported by all the papers, and asked what we thought. All of us were confused as the reporting varied so much, depending on the persuasion of editorial licence. He told us, ‘That is why you must always find out the truth yourself; you cannot always believe what you read.’ ”12 Into Hockney he drummed the adage “Never mind what the neighbours think.”

Breakdown en route to Aldermaston (left to right: John Loker, David Hockney, unknown) (illustration credit 3.2)

Over the Easter weekend of 1958, CND held the first of its Alder-maston marches, a four-day anti-nuclear protest march from Trafalgar Square in London to the atomic weapons establishment at Aldermaston in Berkshire. Hutton Terrace became a hive of activity, with Kenneth busy painting posters in the attic in his best suit, much to the annoyance of Laura, while Hockney and John Loker sorted out their own posters printed by Rod Taylor. “They were the kind of thing I was doing in graphic design,” Loker recalls, “with big bold letters. I remember one that I particularly liked which just had huge letters filling the whole page saying BAN THE BLOODY BOMB. Bloody was painted in red.”13 Taylor bought a clapped-out old car for a few pounds, and he, Hockney and Loker all piled in and drove down to London for the march, a saga of punctures, changing tyres, bumpers falling off, and cold nights spent in sleeping bags in church halls that was to be repeated over the next few years.

The autumn of 1958 was a happy time for Hockney. John Loker had left Bradford College and, as a fellow conscientious objector, had decided to fulfil his military service in Hastings, doing agricultural work. With Peter Kaye and Dave Oxtoby, he rented a cottage where Hockney joined them at the end of September, and for a while he, Kaye and Loker worked as apple-pickers at an orchard along the coast in Rye, following the itinerant harvesters, and collecting anything they might have missed, such as the fruit from the tops of the trees. Because their names were Hockney, Kaye and Loker, they called themselves Hockeylok Apples Inc.

When the work started to get monotonous, Hockney decided to apply for another hospital job. “We are beginning to get things ship-shape down here,” he wrote to his parents on 10 October. “(That doesn’t mean we’ve moved into the sea.)” On 21 October he told them, “I commenced work at St. Helen’s Hospital Hastings yesterday. It is alright. The ward is rather similar to the one at St. Luke’s … Dad, don’t worry about my appearance at the hospital, we are keeping house very well, and in fact I think we can congratulate ourselves. We even washed some sheets the other day and I ironed them all—and they were ‘Persil White.’ ”14 As an orderly in the heart patients’ ward his jobs included bathing the patients, and occasionally those who had died. Hockney struck up a friendship with the mortuary attendant and on more than one occasion found himself eating his picnic lunch surrounded by the bodies of the dead.

With one year left before starting at the Royal College, Hockney began to think about painting again, and he and his friends enrolled for Monday-evening life-drawing classes at Hastings College of Art. He also wrote to his father on 21 October instructing him to dispose of his surplus pictures. “Dad, if Mr. Ashton is interested in buying pictures cheap, all those stacked in the attic can be sold, apart from the Road Menders. This painting is on a canvas worth at least £5, so that would be ‘cheap’ at anything around say £10.” He was sending paintings to the Yorkshire Artists’ Exhibition, to next year’s Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, and had already started three new pictures and done quite a bit of drawing. He finished the letter by telling him that they had had a visit from David Fawcett, their fellow student at Bradford. “… he was saying that this new school he is teaching at wants some original paintings, and they are interested in young painters, so he’s put our names forward—not bad eh.”15

While Hockney worked out his time in the hospital, John Loker and Peter Kaye were employed on a farm, initially pulling mangles, a really horrible job. On the whole, however, it was a good year. “At weekends,” Loker recalls, “Norman Stevens, who was already at the Royal College, used to come down and bring various students with him. Dave Oxtoby used to visit from the Royal Academy Schools with friends, and we used to go round the countryside seeing things like the Lewes bonfire, where they burn an effigy of the Pope. They were some great times, and it gave us the opportunity to meet some students of the Royal College, and occasionally we used to go up to London and hang out with them, so when we actually got there it wasn’t so strange.”16

When Hockney finally arrived in London in September 1959, he was entering one of the best art schools in the world at a time when it was on the threshold of one of its most productive periods. The Royal College of Art was spread about South Kensington in what the principal, Robin Darwin, described as a series of “shacks and mansions,”17 with some sites a quarter of a mile from each other. While the main premises on Exhibition Road, behind the V&A, housed the School of Painting and Graphic Design, the School of Sculpture was in a shed in Queen’s Gate, the School of Fashion in a large house in Ennismore Gardens, and the Junior and Senior Common Rooms were in the Cromwell Road. However unsatisfactory the set-up, the college’s results spoke for themselves: recent graduates included Peter Blake, Frank Auerbach, Robin Denny, Bridget Riley and Richard Smith.

Robin Darwin had already wrought miraculous changes at the college since arriving, on 1 January 1948, to discover “Morrison Shelters doing duty for printing tables in the Textile Department … no drawing offices anywhere in the College, and only two studios for the whole School of Design; nor was there a lecture theatre. There were virtually no records of any sort, no paintings or other works by former students … A single secretary served the whole of the College …”18 An unconventional figure, Darwin had been secretary to the British Camouflage Committee during the war, where he had brought in artists to work alongside architects, engineers and scientists. Striking in appearance—“brooding with thick dark hair, heavy spectacles underlined by an equally heavy moustache, a piercing eye that stared one down, a merciless tongue, an old Etonian tie and a dark double-breasted business suit, a perpetual cigarette”19—he had become a brilliant administrator as a result of his wartime experience, and by appointing lively professors and letting them manage their own departments in the way they wanted he soon had the place up and running. The senior tutor was Roger de Grey, a distinguished landscape and still-life painter, who was not afraid to speak his mind, and alongside him were Professors Carel Weight, Ruskin Spear, Ceri Richards, Robert Buhler, Colin Hayes and Mary Fedden, the first woman ever to be employed at the college. By the time Hockney arrived the college was thriving, and there was a real buzz about it. He arranged to lodge with Norman Stevens in one tiny room of an Earls Court boarding house, 47 Kempsford Gardens, owned by an actor, John Bennett. Hockney wrote home on 3 October, “Dear all, I have settled down and am working hard. The digs (one room with two beds, gas ring and wash basin, and kitchen, toilet and bath downstairs) are about 10 minutes walk from the college or a 3d ride on the tube …”20

Skeleton, 1959 (illustration credit 3.3)

On his first day at college, Hockney felt like “a little provincial. I thought that, coming from a place like Bradford, everyone else would be much more sophisticated than me.” Though he soon found out that this was not the case, he did suffer from the occasional teasing about his then quite thick Yorkshire accent. “There was quite a lot of ‘trooble at mill’ stuff to begin with, which I’d never really come across before. It didn’t worry me. In fact, it quite amused me, though I did sometimes bite back. I remember saying to someone who was taking the mickey, ‘Well, if I drew as badly as you, I’d keep my mouth shut.’ I wasn’t intimidated at all.”21 It had also occurred to him that going to the Royal College when he was that little bit older was probably a good thing, as he would get more out of it, and he had Norman Stevens to keep an eye on him. “My first impression of David and Norman,” remembers Roddy Maude-Roxby, the editor of the college magazine, Ark, “was of these two northern lads who were like a comic double act, and they both spoke as if each other’s mother had told him to look after the other lad. People used to imitate their accents as well, but I think they were quite at ease with it. They both had a great sense of humour and a lot of rapport with people.”22

The students Hockney met in those first days were an unusual mishmash, most of them stepping out into the world for the first time. Of those his own age perhaps the most sophisticated was Allen Jones, a Londoner, who had not only attended another leading art college, Hornsey School of Art, but had already travelled abroad, in particular to Paris, where he had fallen under the influence of Delaunay and had come back to paint large, colourful, abstract canvases. A jazz lover with a penchant for wearing three-button suits, at first Jones felt a little out of place among his fellow students. “When I arrived at the RCA,” he recalls, “I seemed to be the only person not from the provinces. The only time I had heard north country accents was when I heard comedians, so I was always expecting punchlines every time anyone spoke with a northern accent even though it wasn’t funny.”23

With one exception, the rest of the new intake were pretty green. There was Peter Phillips who came from Birmingham, where he had studied at Birmingham College of Art; Derek Boshier, whom Hockney had befriended at his interview, and who came from Yeovil Art College in Somerset; and Norman Stevens, Hockney’s fellow Bradfordian. In addition, there was also an American ex-serviceman, Ron Kitaj, who was a few years older than the rest of them and correspondingly more worldly.

This was an interesting collection of young men, thrown together at a time when there were stirrings beneath the surface of austerity Britain. “Growing up in the 1950s, we dreamed the American dream,” wrote the film-maker Derek Jarman thirty years later. “England was grey and sober. The war had retrenched all the virtues—Sobriety and Thrift came with the Beveridge plan, utility furniture and rationing, which lasted about a decade after the end of hostilities. Over the Atlantic lay the land of Cockaigne; they had fridges and cars, TV and supermarkets. All bigger and better than ours … Then as the decade wore on, we were sent Presley and Buddy Holly, and long-playing records of West Side Story, and our own Pygmalion transformed. The whole daydream was wrapped up in celluloid … How we yearned for America! And longed to go west.”24

Having spent two years doing relatively little painting, Hockney was determined to make up for lost time. His problem was how to begin. “The first thing I thought,” he says, “was that I had to unlearn everything I’d learned at Bradford, because they didn’t really deal with modern art, and that was something I had become aware of.” A powerful new influence was American painting, which he’d been exposed to for the first time in December 1958, when he went to the Jackson Pollock show put on by Bryan Robertson at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, and realised that here was a modern artist who was part of an utterly different tradition. “I’d become aware of how many artists came out of Picasso—Henry Moore, Francis Bacon and so many others—and suddenly there was this very free-looking art which when you looked closely at it you could see how organised it was. It was not just random splashes of paint. There was order to it. It was because it was so unlike Picasso and so American that young art students found it so lively and fresh.”25 Seeing the Pollock show made Hockney realise that his teaching had never addressed the problems of the modern movement, partly, he suspected, because his teachers didn’t really understand it.

Temporarily at a loss, Hockney threw himself back into drawing. “I hadn’t done any drawing to speak of for a couple of years, so I thought I’d get back into it by drawing something a little bit difficult and complicated. There was a skeleton hanging up in the studio so I decided to draw that. I realised that if I was going to do it properly, drawing in detail the ribcage and the pelvis, etc., then it would take some time and get me back into the routine of work.”26 Establishing a routine was important, and as his living conditions were hardly conducive to work, each morning he would get up at the last possible moment and walk the half-mile to the college from Kempsford Gardens, to be there to start at eight. Invariably he would put his name down on the list to work after hours and stay at the college studios till ten at night, only returning home when he was ready for bed. On Sundays, when the college was closed, he would methodically tour London’s museums and galleries.

Hockney spent six weeks on his two skeleton drawings, executing the first, a vertical study of the skeleton hanging from a rail, in pencil, and the second, a more dramatic study looking down upon it and foreshortening the perspective, in turpentine washes. Because the size of the paper he had access to was limited, as the drawing got bigger, he would just roughly paste on a new piece. Janet Deuters, another painting student, noticing how good the drawings were, told him that because he could draw so well, he should take greater care in the way he glued the paper together. She told her friends about him and word soon began to spread about this extraordinary-looking new student. The drawings rapidly drew praise. “They were a tour de force,” says Allen Jones. “They exhibited so much panache and so much language, but it was done with such authority that you didn’t view it as a trick.”27 The young American, Ron Kitaj, also came to take a look. “During our first days at the Royal College,” he later wrote, “I spotted this boy with short black hair and huge glasses, wearing a boilersuit, making the most beautiful drawing I’d ever seen in an art school. It was of a skeleton. I told him I’d give him five quid for it. He thought I was a rich American. I was—I had $150 a month GI Bill money to support my wife and son. I kept buying drawings from him …”28

Ronald Brooks Kitaj had arrived in England from the United States in 1958 courtesy of the GI Bill, to study art at Ruskin College in Oxford, from where he had graduated to the Royal College of Art. A former merchant seaman, he was five years older than Hockney, and the younger man immediately looked up to him, both for being American and for his experience of the world; Hockney had never been abroad. They discovered a mutual love of reading and Kitaj was able to pass on his knowledge of his favourite American expatriate writers such as T. S. Eliot, Henry James and Ezra Pound; he had also read one of Hockney’s favourite books, George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier. But more than anything it was Kitaj’s attitude to painting that impressed Hockney. He was by far the slowest painter at the college, because he took his time. Painting was something to be studied seriously, he passionately believed, though it was a point of view not held by every student at the college. “There were these two groups of people at the RCA,” Allen Jones recalls, “and the difference between them was noticeable. I was aware that some of the people there were behaving like men. While I was drawing away, it was often a source of wonder to me that some of my fellow students had been digging trenches in Korea only six months previously. These students were men and they handled themselves differently. They all blew their grants immediately and bought Lambrettas and hung out at the Serpentine picking up girls, and I remember thinking, ‘That’s all very well, but what will they do for buying paint?’ ”29

Still finding his way, and not a little spurred on by the large abstract-expressionist-style canvases he saw being worked on by his fellow students Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips, Hockney decided to follow up the skeleton drawings with his own attempts at abstraction. In working on these, he was much influenced by a 1958 show at the Wakefield City Art Gallery, a retrospective of the work of the Scottish artist Alan Davie. Davie’s use of symbols and graffiti in his quite unique paintings seduced Hockney, as did the gaudy colours he employed. The fact that Davie was also a recipient of the Gregory Fellowship in Painting from Leeds University and was working in Leeds at the same time Hockney was at Bradford made him all the more real, and Davie was very much in Hockney’s mind when he started work on a series of large images painted on pieces of four-foot-square hardboard. “Young students had realised,” he later wrote, “that American painting was more interesting than French painting … American abstract expressionism was the great influence. So I tried my hand at it. I did a few pictures … that were based on a kind of mixture of Alan Davie cum Jackson Pollock cum Roger Hilton. And I did them for a while, and then I couldn’t. It was too barren for me.”30

These experiments with abstraction lasted about three months through the winter of 1959–60, and most of what Hockney produced was either destroyed or painted over by him, or by fellow students needing a fresh supply of hardboard. The few that have survived were given proper titles, suggesting a dislike for the fashion set by Pollock of referring to paintings by numbers, which, Pollock claimed, made “people look at a picture for what it is—pure painting.”31 Thus Erection suggested the stirrings of an as-yet-subverted desire to address sexual themes, while Growing Discontent firmly stated Hockney’s ever increasing dissatisfaction with the road he was going along.

Hockney discussed his insecurities in many conversations with Ron Kitaj who, far more than any of the college staff, he came to look upon as his mentor. “He had an incredible conscience about his work,” said Hockney, “which brushed off on other people. He wasn’t flippant or easily put off work … He stood there in front of a canvas from 10:00 a.m. till 5:00 p.m. and worked.”32 Since Kitaj didn’t drink or smoke and liked to be in bed soon after ten, their discussions usually took place over a morning cup of tea or coffee in the cafe of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Hockney confessed that he was so frustrated by what he was doing that it sometimes seemed pointless to go on. “He told me,” Hockney remembers, “that I should look upon painting as a means of exploring all the things that most interested me, and that I should paint pictures that reflected this. This was the best advice he ever gave me.”33 Kitaj probed his interests, discovering them to be politics, literature, relationships, vegetarianism, and encouraged him to consider using these as subject matter for paintings. “I thought it’s quite right; that’s what I’m complaining about, I’m not doing anything that’s from me. So that was the way I broke it. I began to paint those subjects.”34

The first paintings were inspired by vegetarianism. “I was a militant vegetarian at the time, and handed out leaflets about the cruelty involved in making the terrible sausages you got in the common room. At Kitaj’s suggestion I started painting vegetarian propaganda pictures and they became absurd and interesting.”35 Once again painted on hardboard, these were abstract paintings with various vegetables represented by areas of colour—red for tomatoes, orange for carrots, green for lettuce, for example—with the names of the vegetables written on them in paint. The employment of words, an idea that came from the cubists’ use of collage, also forced the spectator to confront the interests of the artist, in the same way that the words on Kenneth Hockney’s posters confronted people with his ideas. “You realise,” says Hockney, “that the moment you put a word on a painting, people do read it. It’s also like an eye. If there’s an eye in a painting, you can’t not look at it, and you can’t not read a word.”36 Using words also helped him solve a problem he had been grappling with for some time, which was his reluctance to use figures in his paintings for fear of being considered “anti-modern.” “When you put a word on a painting,” he wrote, “it has a similar effect in a way to a figure; it’s a little bit of a human thing … it’s not just paint.”37 That the vegetable paintings have long since disappeared seems irrelevant in the light of what Hockney did next, which was finally to address the one, and most important, subject that he had been till now studiously avoiding: his sexuality.

David Hockney in Painting School (illustration credit 3.4)

Space was at a premium in the Painting School. Once the new students had graduated from working in the Life Room and the Still Life Room, which was compulsory in the first six weeks, it was up to them to stake out a space in the studios, which were part of the old V&A. Hockney used to try and grab the biggest area by getting in before anyone else, but those who were not quite so determined ended up in the corridor, where partitions had been erected to take the overflow. It was here that Kitaj worked, in a space he shared with another, older, painter, Adrian Berg, who had previously studied at Chelsea School of Art and had already been at the college for a year. Berg was openly gay, and when Kitaj introduced the two, they immediately hit it off. Just as at Bradford, Hockney’s reputation had preceded him: Norman Stevens had repeatedly warned Berg, “You wait till Hockney arrives.”

Adrian Berg was the first man that Hockney had met for whom being gay was not a problem. “I wasn’t confused about my sexuality,” he recalls, “though I was cautious, because you had to be in those days. I was queer and David was queer, and we were of help to one another.”38 He also appealed to Hockney because he had studied literature at Cambridge and was able to share his great knowledge of books. They discussed poetry, and Berg told him of the work of the homosexual poets Walt Whitman and Constantine Cavafy. “I suddenly felt part of a bohemian world,” Hockney remembers, “a world about art, poetry and music. I felt a deep part of it rather than any other kind of life. I finally felt I belonged. I met kindred spirits and the first homosexuals who weren’t afraid to admit what they were. Adrian Berg lived in a free world, and fuck the rest of it. I thought, ‘I like that. That’s the way I want to live. Forget Bradford.’ Once I accepted all this, it gave me a great sense of freedom, and I started to paint homosexual subjects.”39

Baring his soul on canvas was not easy for Hockney who, though gradually blossoming, was still quite shy. Contemporaries remember him looking at his feet a lot when speaking. Searching for a way of expressing his deepest emotions in his work while retaining some feeling of anonymity, he looked to Jean Dubuffet, whose spindly figures took their inspiration from children’s art. “I got taken with the deliberate childish thing,” he recalls, “and felt I could use this to deal with a lot of subjects and ideas.”40 He also drew on graffiti as an inspiration, and reviewed for the college news-sheet the graffiti in the men’s toilet of the students’ common room, as if it were art hanging in the Latrine Gallery and he was the critic from Art Review. To begin with, he approached the subject of his sexuality in his paintings very tentatively, one of his first paintings about love being simply a picture of a heart with the word LOVE written in small letters along its lower edge. As he developed his technique, however, managing to keep one step away from his subject, he grew gradually bolder and was soon painting the word QUEER on a canvas and using the then explicit word as its title. Graffiti was also the inspiration for a series of “Fuck” drawings he produced during this period.

By the end of his first year at the RCA, Hockney was beginning to find himself. The painting staff, however, seemed to be at a loss as to know how to deal with the class of ’59. To begin with, they didn’t like the students doing enormous paintings, and Peter Phillips, Derek Boshier and Kitaj were all painting pictures of motorcyclists, movie stars and cowboys and Indians on a large scale. Add to this the fact that the painting studio had become so cluttered with big canvases that it was like trying to enter a maze, and it is perhaps understandable that this older, wartime generation of professors came to be so antagonistic towards their charges. “The staff said that the students in that year,” wrote Hockney, “were the worst that they’d had for many, many years. They didn’t like us; they thought we were a little bolshy.”41 Allen Jones remembers the day a warning light came on. “One day Ruskin Spear, who was going round looking at the work of each student, came up to my picture and asked, ‘What’s going on here? What’s all this bright colour?’ Everyone was painting away, secretly listening to me getting a barracking, and I was thinking, ‘He’s just got to be joking.’ But then I realised he was absolutely serious and he could not understand what I was doing, and would not be able to talk about it. I asked him what was wrong and he said, ‘This is a grey day, this is grey South Kensington, this is a grey model, she’s got grey prospects, so what’s all this red and green all over the place?’ ”42

Jones was one of the painters who stayed on regularly to paint after hours, till the doors closed at ten, and one particular evening, when they were all dying for a cup of tea, Hockney said he couldn’t be bothered to walk to the nearest cafe, and in typically anarchic style suggested they should raid the staff common room, where there was a plentiful supply of tea and biscuits. As long as they replaced whatever they used, no one would be any the wiser. “So we started going there to have a quick cup of tea,” Jones recalls, “and David would read the staff memos to all of us, and I kept thinking we were on dangerous ground. I remember there was a memo from Robin Darwin, the principal, to Carel Weight and company just saying ‘Who is running the painting school?’ ”43

The result of the memo was that the painting students who were thought to be out of line were all gathered together and were read the riot act by Carel Weight, who told them that in their first year they were there to observe nature and prove themselves to be proficient, and that they should wait till their third year to experiment. But Darwin wanted more than this. Pour encourager les autres, he wanted a head on the block, and that head turned out to be Allen Jones. “For me it was the end of my world,” says Jones. “I demanded an interview with Robin Darwin and he agreed to see me. He told me he had five minutes because he was going off to a lunch appointment. So I said my piece, and at the end of it he said, ‘Well, I’ve known you for five minutes and I’ve known Prof. Weight for most of my life. So who do you think I should believe?’ and that was that.”44 Most people were baffled by Jones’s dismissal, but his friend Peter Phillips always believed that they singled him out because his determination and independence made him potentially the most dangerous student. As for Hockney, of whom the same might be said, it was the skeleton drawings that had saved him.

By the time Allen Jones learned his fate, it was the last day of term and most of the students had gone home. Hockney had returned to Bradford and a summer job as a caretaker at a school in the centre of the city and next to the library, where he went every day. Remembering his talks with Adrian Berg, he made two literary discoveries there which would inspire future work. First were the poems of the American writer Walt Whitman, many of which had explicit homosexual themes. “In the summer of 1960, I read everything by Walt Whitman. I’d known his poetry before, but I’d never realised he was that good. There are quite a few of my paintings based on his work.”45 He also explored the work of the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, whose work was not put out on the open shelves, being considered unsuitable for the general reader, and which had to be asked for specially. Hockney later admitted that he stole the library’s copy of Cavafy’s poems translated by John Mavrogordato as it was out of print. “I read it from cover to cover, many times, and I thought it was incredible, marvellous.”46

Hockney returned to college that autumn for the start of his second year fired with enthusiasm, and looking forward to the fact that his friends from Bradford Art School, John Loker and Peter Kaye, were taking up places at the Royal College, while Dave Oxtoby was going to the Royal Academy Schools. Since Norman Stevens had now graduated, they all moved into the Kempsford Gardens flat, creating an extra room by erecting a partition across the tiny bedroom. It was horrendously cramped and when the landlord, John Bennett, fresh from playing the part of the Marquess of Queensberry’s Friend in The Trials of Oscar Wilde, wanted to move in an actor friend of his who had fallen on hard times, he offered Hockney the opportunity of sleeping in the shed at the bottom of the garden at a cheaper rent. “I liked being on my own, so I jumped at it,” he recalls. “It was literally a garden shed with one bed and an electric heater. It had to have electricity because I needed a light, but it was probably quite illegal. It really wasn’t very comfortable, and there was no water. Every three weeks I would have a bath in the house. I did everything at the Royal College. I would wash there in the sink, because it had hot water. In fact, Carel Weight once caught me having a bath in the sink! I had my mail delivered there, even my milk.”47

Hockney had a clear two hours before anyone else arrived: people would start coming in and chatting at 10 a.m., and it was then time to have a cigarette. He knew the times when he couldn’t get work done, and which were the good working hours, and he was always making sure that he would have the space to work and the time to work. He also figured out that you could only work for about an hour after lunch. “I noticed that most people began to end the day about three o’clock and then they started to put things away and would go round and talk to the other students. I noticed that they’d come to me at around three for cigarettes, because I always had plenty of cigarettes. So at three o’clock in the afternoon I started to go to the cinema. Anyway, it was the best time to go because the cinemas were empty and I could put my feet up on the seat in front and be quite carried away, and if I wanted an ice cream the usherette would come straight to me. Then when I came out of the cinema at six, I would go back to the college and they had all gone home. I would then have the place to myself again. So I got to see the films and missed the times when they were pulling me away from the easel.”48

The autumn term saw the arrival of another American who was to have a profound influence on Hockney. Mark Berger was a thirty-year-old mature student on a year-long scholarship break from teaching painting at Tulane University in New Orleans. His first day at the college is still etched upon his mind. “I arrived there before the semester began,” he reminisces, “and they gave me a cubicle. I was totally alone in this building, when suddenly this character walks in wearing striped clothing and looking like a prisoner. It was David Hockney and he had been assigned a cubicle right next to me. We were the only two people there.”49 Hockney took to Mark immediately because “he was openly gay, very American and very amusing.” He also had a collection of American “beefcake” magazines such as Physique Pictorial and Young Physique that Hockney picked up on right away. “We never said to each other ‘I’m gay’ and ‘You’re gay,’ ” Mark remembers, “but it was just so obvious we were. It was just never discussed.” Mark saw Hockney as a true English eccentric, a man who liked to be regular, but did the irregular. “One time he went shopping because he needed to buy some socks, and he bought a pair of socks which were in fact women’s leggings and they were bright pink, and he said to me, ‘God forbid I should be in an accident and they find me wearing bright pink stockings!’ But he enjoyed the idea.”50

Before the summer holidays, Hockney had been developing a series of “Love” paintings in which he further explored the theme of homosexuality. “They were inspired,” he recalls, “by the fact that the sex life of London had opened up to me, rather than by any one particular lover.”51 These were not yet figurative pictures, but abstract compositions in which words and phrases were used to help make his meaning clear. While the first two of these feature a large red phallic shape rising from the lower edge and the word “love” prominently displayed, it is the third one, titled The Third Love Painting, that is the most extraordinary, for it brings the subject of homosexual desire to the fore and invites anyone looking at it to become a voyeur. Hockney achieved this effect by scattering the canvas with the kind of crude graffiti he had seen in the public toilets of Earls Court Underground station. “… you are forced to look at the painting quite closely,” he wrote. “… You want to read it … When you first look casually at the graffiti on a wall, you don’t see all the smaller messages; you see the large ones first and only if you lean over and look more closely do you get the smaller more neurotic ones.”52 Thus a close look reveals an invitation to “Ring me anytime at home”; a saucily ambiguous propaganda slogan, “Britain’s future is in your hands”; and the information that “My brother is only seventeen,” while the artist’s inner self calls out, “Come on David, admit it.” Alongside these base sentiments, written on the same phallic shape as appears in the previous works from the series, are the closing lines of “When I Heard at the Close of Day,” a poem by Walt Whitman which celebrates the perfect love that can exist between men:

For the one I love most lay sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night,

In the stillness, in the autumn moonbeams, his face was inclined toward me,

And his arm lay lightly around my breast—and that night I was happy.

The Third Love Painting was completed in the autumn of 1960, a time when Hockney was beginning to show a new self-confidence rooted in the knowledge that he’d finally reached a point at which he could make paintings for himself about the things that excited him. One of his crushes at the time was the young singer Cliff Richard. Though classical music had always been Hockney’s first love, his brother John had given him an early Elvis Presley record, and this had started him off listening first to Elvis, then to Tommy Steele and finally to Cliff Richard, who in 1959 had released his number-one album, Cliff Sings, and starred in the gritty movie Expresso Bongo. With his greased-back hair, leather jackets and skin-tight trousers, Cliff was, Hockney remembers, “a sexy little thing,” a line echoed by a Daily Sketch headline that asked: “IS THIS BOY TOO SEXY FOR TELEVISION?”

Cliff’s latest hit single was the Lionel Bart song, “Living Doll.” In a series of studies and drawings connected to a new painting, Doll Boy, Hockney made Cliff himself the object of adulation rather than the girl implied in the song’s lyrics. Doll Boy is an important picture because it is one of the first of his paintings in which a figure begins to emerge, clothed in a white dress on which is written the word “QUEEN,” leaving one in no doubt as to the meaning of the title. The figure is identifiable as Cliff Richard by the notes emanating from his mouth signifying a singer, and by the figures 3.18, which are written beneath him; these are based on a childish code used by Walt Whitman to disguise the name of his lover, Peter Doyle, in which 1 = A, 2 = B and so on. 3.18 therefore translates as C.R.

This code came into play again in a painting executed at about the same time in which the use of the figure is further explored, and which Hockney referred to as his “first attempt at a double portrait.”53 Its title, Adhesiveness, is a word used by Walt Whitman to describe friendship; in the poem “So Long!,” he writes:

I announce adhesiveness—I say it shall be limitless, unloosen’d;

I say you shall yet find the friend you were looking for.

Adhesiveness is the first picture in which Hockney portrays himself and thus explicitly declares his homosexuality, for it depicts two men engaged in the act of lovemaking, apparently interlocked in the 69 position. One figure is identified by the numbers 4 and 8 for David Hockney, the other by 23 and 23 for his hero, Walt Whitman. “What one must remember about some of these pictures,” Hockney later wrote, “is that they were partly propaganda of something I felt hadn’t been propagandised, especially among students, as a subject: homosexuality. I felt it should be done.”54 It was an attitude that was to establish him as something of a hero to campaigners for gay rights over the next few years.

“David was very erudite,” wrote Peter Adam, a young friend of the artist Keith Vaughan, after a visit to Kempsford Gardens, “and could talk for hours on almost any subject: Walt Whitman, Gandhi, Duccio, Durrell or Cavafy. He struck me as a strange mixture of modesty and self-assurance. He was so intensely alive that ideas just came toppling out, interlacing the most contradictory ideas in a logical pattern.”55

Charged with energy, Hockney was quite happy to draw on an enormous variety of influences. At the time, Ron Kitaj, Peter Phillips and Derek Boshier were all drawn towards pop art, depicting the everyday objects of mass culture. “We weren’t interested in wine bottles and fruit,” Boshier recalls. “We were interested in the world we lived in, in sex and music and culture and advertising. There was a painting by John Bratby which had a cornflakes packet in it, and so I started to paint cornflakes packets and got into pop art.”56

Hockney, too, dipped his toes into these waters, in a series of three “Tea” paintings. Arriving at college before the Lyons Corner House at South Kensington had opened, he always made sure he had a small teapot and a cup, a bottle of milk and plenty of tea—his mother’s favourite variety, Typhoo, “The tea,” as the advertisement ran, “that puts the ‘T’ in Britain.” The distinctive red-and-black packets, piled up on the floor when they were empty along with the tubes and cans of paint, became his inspiration. “This is as close to Pop Art as I ever came,” admitted Hockney,57 whose questing nature would never allow him to become too narrowly concerned with solely contemporary images. These paintings were closely followed by a number of pictures based on playing cards, inspired by a book on the history of cards given to him by Mark Berger.

David Hockney and Derek Boshier in Painting School (illustration credit 3.5)

So prolific was Hockney’s output at this time that he ran out of money to buy paint, the consequences of which proved to be extremely important for his subsequent career. Discovering that the printmaking department—headed by the distinguished Edwin La Dell, a fellow Yorkshireman—gave out free materials to the students, and armed with the knowledge of lithography he had gained in his first two years at Bradford, Hockney decided to try his hand at some printing. Under the tutelage of a fellow student, Ron Fuller, he learned the basic techniques and produced three masterful etchings. The first of these, Myself and My Heroes, shows the figures of Walt Whitman, Mahatma Gandhi and David himself standing against a background of three panels, as though they are figures in a medieval triptych. Whitman and Gandhi both have halos, while Hockney, wearing an army cap, stands admiring them. Once again, words and phrases play an important part. “For the dear love of comrades,” from his poem “I Hear It Was Charged Against Me,” is written on Whitman. Gandhi has the words “Mohandas,” “love,” and “vegetarian as well” around him, while Hockney, at a loss to know what to say about himself, has simply written, “I am 23 years old and wear glasses.” This etching was followed by one based on playing cards, Three Kings and a Queen, and by The Fires of Furious Desire after William Blake’s poem “The Flames of Furious Desire.” The three completed prints demonstrate a mastery of the craft that was to serve him well in the future, even after so short an apprenticeship.

At the end of the autumn term Mark Berger tried to involve Hockney in the annual Royal College Christmas Revue, the idea being to parallel the satirical comedy that was being pioneered by people such as Jonathan Miller, Peter Cook, Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett in Beyond the Fringe, the hit show of the 1960 Edinburgh Festival. The revue was produced by Berger, with the theme of the Hollywood musical, but attempts to persuade Hockney to dress up in drag and sing a number fell on stony ground. This was primarily because only a few weeks previously a young painter called Patrick Procktor, who was studying at the Slade, had talked Hockney into attending their drag ball. “So I went to Woolworths,” Hockney later told Gay News, “and I got these eyelashes and makeup and I had a T shirt printed with Miss Bayswater on it. I had these rubber tits and I shaved my legs. I thought, ‘I’ll swish into the Slade at 9.30.’ I arrived and I was the only one in drag. I thought, ‘Fucking hell, what a terrible dull lot of people. Even Patrick had let me down.’ ”58

The Christmas Revue featured an imaginary conversation in Heaven between Beethoven and Errol Flynn, performed by Roddy Maude-Roxby and Derek Boshier; Janet Deuters, in a costume of her own design, doing a striptease to “You’ve Gotta Have a Gimmick” from Gypsy; and Berger himself, got up in top hat and tails, singing “I’ll Build a Stairway to Heaven” with Pauline Boty, who was studying stained glass, and was known as “the Wimbledon Bardot” because of her resemblance to the French film star. Berg also wrote a skit making fun of the kind of avant-garde theatre that was going on in New York at the time. “I had Janet Deuters sitting up on a chair eating a banana, and someone crawling under her speaking nonsense poetry. David didn’t like it at all. I remember he was up in the balcony drinking beer shouting ‘What a crock of shit! What is this lousy stuff?’ He was definitely not into avant-garde, though strangely enough he began to do things in his paintings that were extremely advanced.”59

The revue also served another purpose in that it brought together students from all the different departments—fashion, graphics and industrial design—creating a great feeling of camaraderie. Favourite out-of-hours haunts included the Hoop and Toy pub round the corner in Thurloe Place, later to feature as a location in Roman Polanski’s film Repulsion, and, once last orders had been called, the Troubadour on the Old Brompton Road, a popular hangout for artists, poets and musicians, or the Hades coffee bar on Exhibition Road. “They served spaghetti in bowls for half a crown,” Hockney remembers. “You had to sit at any table, so if there were six of us and there was a table which already had three people sitting at it, they’d send in me and Norman Stevens to go and sit at it and talk loudly to drive the other people away, so our gang could take it over.”60

Cinema was another uniting influence. The Royal College had its own film club, whose unmissable weekly meetings introduced them to the films of Eisenstein, Buñuel and Renoir. “We used to go to a lot of movies,” Hockney recalls. “As well as the college film club, there was the International Film Theatre in Westbourne Grove, the Classic in Notting Hill and the Paris Pullman in Drayton Gardens. We saw French films, Russian films and Italian films. Though I could be quite dismissive of French pretension, I was very taken with L’Année dernière à Marienbad.”61

In February 1961, Hockney exhibited in the annual “Young Contemporaries” exhibition at the galleries of the Royal Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. Started in 1949 by Carel Weight as a showcase for student work, it was to give successive generations of young artists their first professional outing. Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff, John Bratby, Edward Middleditch, Richard Smith, Robin Denny and Peter Blake had all cut their teeth at it. Peter Phillips was that year’s president, and Derek Boshier, Allen Jones—now doing teacher training at Hornsey College of Art—and Patrick Procktor were on the organising committee. Together they appointed as judges Anthony Caro, Frank Auerbach and the influential critic Lawrence Alloway, who was assistant director of the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts) and the originator of the term “pop art.”

“At first we hung the show like a sketch club,” Allen Jones remembers, “pasting the walls with paintings as best we could. But when it had been hung and everyone had gone home, I was left with Peter Phillips and we looked around and we thought this is not the way to do it. We thought we should put all the pictures that we liked and identified as an idea on one wall, and all the rest on another wall. So we gave Kitaj a complete wall, and then we had the other Royal College paintings facing the Slade. The Slade at the time was all under the influence of Bomberg, so it was all what I called ‘struggled mud,’ while on this other wall there was just this vibrant range of paintings.”62

The paintings chosen by the committee included images of toothpaste tubes by Boshier, fruit machines by Peter Phillips and a big red bus by Allen Jones. Hockney’s work in the show, Jones believes, was particularly inventive. As well as Doll Boy, he showed The Third Love Painting and the first two “Tea” paintings. In the catalogue, Lawrence Alloway drew attention to the group’s use of “the techniques of graffiti and the imagery of mass communication. For these artists the creative act is nourished on the urban environment they have always lived in.” Though he didn’t use his term “pop art” in the introductory essay, this is precisely the label that was given by the press to the work of the Royal College group in this show, and it was one that stuck. Suddenly the attention of the art world was drawn to a collection of young artists who were producing remarkable work while they were still at college, a previously unheard-of phenomenon. “This year’s Young Contemporaries at the RBA,” wrote Keith Sutton in the Listener, “is a particularly good and lively one. The pictures … confirm at least one tentative hope, that things have got better since the war; namely that English artists can cope with scale in painting without diminishing content.”63

This exhibition was the first really significant moment in Hockney’s student career. “It was probably the first time,” he commented, “that there’d been a student movement in painting that was uninfluenced by older artists in this country, which made it unusual. The previous generation of students, the Abstract Expressionists, in a sense had been influenced by older artists who had seen American painting. But this generation was not.”64 People began to beat a path to the Royal College painting studios. “They used to come in and wander round,” Hockney remembers. “You would have finished paintings lying around and people would stroll in and look at them, so it was a bit of an exhibition space. You could show off in it, and I’m sure I did.”65 One person who stopped by was the photographer Cecil Beaton, himself a talented artist. “When I went to the college to take a few lessons,” he wrote in his diary, “David and his friends were referred to by the professors as ‘the naughty boys upstairs.’ I visited them up there and found David at work on a huge Typhoo Tea fantasy. Everyone seemed to be doing what they wanted and loving it … I bought an indecent picture, Homage to Walt Whitman,66 by Hockney who brought it round when Pelham Place [Beaton’s home] was in the throes of building alterations. The workmen were startled at his appearance.”67

By far the most important thing that happened to Hockney, however, as a result of this show was that he attracted the attention of an extraordinary young dealer, John Kasmin, who was to change his life forever.