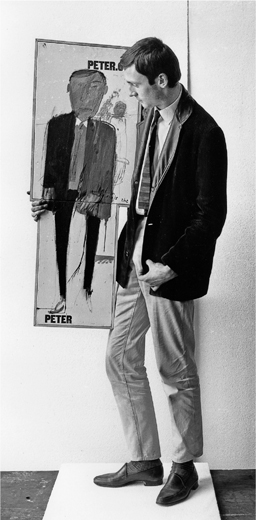

Portrait of John Kasmin (illustration credit 4.1)

Portrait of John Kasmin (illustration credit 4.1)

John Kasmin was the 27-year-old son of a family of Jewish immigrants from Poland. He had grown up in Oxford, where his father ran a garment-manufacturing factory, and had been happily studying classics at Magdalen College School until the business ran into financial difficulties. He was withdrawn from school, put to work in the family business and made to take night classes in accounting, going from a delightful life reading Greek poetry to a miserable one on the factory floor. Determined to escape and get away as far as possible from this dreary existence and a deteriorating relationship with his father, at seventeen he used his bar mitzvah money to travel to New Zealand, where he attended university for a while before dropping out and joining the bohemian fringe of New Zealand life. “I became a sort of roving character,” he recalls. “I made many friends and had a very varied and interesting life, rather like being a character in Kerouac’s On the Road.”1 In 1956 he returned home, calling himself a poet, and settled in London, soon assimilating himself into the artistic life of Soho, where he would take coffee at Torino’s, hang out in David Archer’s poetry bookshop in Panton Street, and drink at the French House pub, the Colony Room or the Cave de France. Among his favourite places to visit, particularly in the afternoons, was an art gallery in D’Arblay Street, Gallery One.

In the art scene of the 1950s, money was never the principal consideration, and many galleries were pretty shambolic, often run by slightly rakish gentlemen who spent as much time on the telephone to their bookmakers as they did in the gallery. Victor Musgrave, the owner of Gallery One, was an eccentric bohemian poet married to the portrait photographer Ida Karr, who was renowned for her pictures of artists. Theirs was an open marriage and the whole set-up at 20 D’Arblay Street, where the gallery was on the ground floor and the basement rented out to a picture framer, reflected the bohemian world that Soho then was. On the first floor, Colin MacInnes, the author of City of Spades and Absolute Beginners, had a room, while Ida had her studio, sitting room and bedroom on the top floor. She and Victor both had very active sex lives, he with a variety of prostitutes who inhabited the neighbourhood, she with lovers of both sexes who would come and go at all hours. “… lovers, lodgers and friends became all mixed up in the sleeping arrangements as those with not enough money to eat stayed to eat, and those with nowhere to stay stayed over, lovers came and went and lodgers brought in their own companions.”2

“I was sitting in my gallery,” Victor Musgrave recalled, “when a small, eager, enthusiastic figure erupted into it and said in this eager breathless way, ‘Hello, hello, are you Victor Musgrave? Where can I meet painters, writers, artists?’ ”3 As a result of this surprising introduction Kasmin soon found himself working as an unpaid assistant to Musgrave, as well as being both lover and studio manager to his wife. He was also paid half a crown a day to do the cooking, and was allowed to sleep in. One room on the top floor served as sitting room, dining room, kitchen, bathroom and bedroom, the last being created by means of a board placed over the bath at night. There was an outdoor lavatory in the backyard. “I liked being there,” Kasmin remembers. “It was one of the hot spots of Soho, a meeting place for writers and artists, and after four or five months I managed to prove my worth in the gallery.”4

The show that finally made Gallery One famous internationally was called Yves le Monochrome and was of the work of the French postmodernist Yves Klein. It took place in 1957, by which time Kasmin had been promoted and was sleeping in the guest bedroom, often with a variety of women. “There was a tremendous amount of sex life that went on in and around the gallery,” he recalls. “Victor was very into prostitutes and had a busy fantasy life, and at that time a lot of the women who went round galleries were very much open to proposition, so there was a lot of action. I would take the under twenty-eights. It was a curious and interesting life.”5

Having cut his teeth at Gallery One and built up a wide range of contacts and friendships, Kasmin moved on in 1959 to work at the Kaplan Gallery in Duke Street, St. James’s, under the distinguished Marxist dealer Ewan Phillips, with whom he shared dalliances with the gallery receptionist, who liked to measure their penises during her coffee break. It was a lively scene, and they put on the first London show of Jean Tinguely, featuring his Meta-Matics, robot-like machines which painted their own pictures, as well as early shows by Leonore Fini and Jean Atlan. During this year, Kaplan also recruited a third employee, a young Jewish refugee of great taste called Annely Juda, who would one day become David Hockney’s dealer.

By now Kasmin had married into art royalty, his wife Jane being the granddaughter of Sir William Nicholson and the niece of Ben Nicholson, and was living in a cold-water flat off Regent Street. He was also the father of a six-month-old son, Paul. The necessity of supporting his family now pushed him in a new direction.

The most commercially minded gallery in London in 1960 was the Marlborough, founded after the war by two Viennese émigrés, Frank Lloyd and Harry Fischer, who were both feared and disliked on the art scene for their habit of poaching artists from other galleries. Their two greatest coups had been to lure Francis Bacon away from his long-standing dealer, Erica Brausen of the Hanover Gallery, who had nurtured him throughout his career, and Lynn Chadwick, Kenneth Armitage and Ben Nicholson from Peter and Charles Gimpel of Gimpel Fils. Among cash-strapped young art lovers, they were also well known for the excellence of the canapés served at their openings. They planned to open a new gallery, across the road from the Marlborough, in Bond Street, to be called the New London Gallery. Its premises were above Lloyds Bank, which appealed to Frank Lloyd, who had anglicised his name from Levy. Though they failed in their attempts to recruit Ewan Phillips to run it, who considered them ungentlemanly and driven by naked greed and power, he did recommend Kasmin for the job. “My instincts told me,” Kasmin remembers, “that it would be dreadful to enter into what was going to be the other side of the art world, the world of money, in which they behaved in a completely contrary fashion to most English art dealers of the time, but I decided to go for the job, and I went along and was interviewed by Mr. Lloyd. My brief was to look for artists as well as to run the shows they sent over to me. They gave me an expense account to take out to lunch people whose goodwill would improve the prospects of the Marlborough Gallery, so I immediately set up accounts in Wilton’s, Prunier’s and a cigar store near Wilton’s. I was constantly looking about for new artists whose work I liked and who might be available.”6

Kasmin worked at the Marlborough for a year, during which time he attempted, with little luck, to promote the work of artists he liked. The problem was that Fischer did not share his taste. Kasmin’s attempt to push John Latham, for example, a conceptual artist who worked in a form of three-dimensional collage called “Assemblage,” was disastrous. Latham’s chosen subject at the time was books, which he would torch and paint, producing walls of burned, blackened and coloured books. “I loved his work and I considered him a visionary,” says Kasmin. “Fischer, on the other hand, who was a lover of books, absolutely hated him, and on the occasion when I took him into Latham’s studio, he was speechless with horror.”7

Kasmin also tried to interest Fischer in David Hockney. As part of his brief to search for new talent, Kasmin had gone to the Young Contemporaries show, and out of the extraordinary and exciting crop showing there had identified Hockney as the best of the bunch. “I liked his touch,” he remembers. “He seemed to have a really original approach to painting that was between figuration and abstraction. It had cheekiness and bravado and it was lively.”8 Of the paintings Hockney was exhibiting, Kasmin particularly loved Doll Boy, which he bought for £40. “I liked the writing, the style, the spirit … and felt very pleased with myself.”9

Keen to get to know the artist better, Kasmin contacted Hockney and invited him to his home in Ifield Road, Fulham, for a cup of tea so that they could talk about the picture. “I told him I’d like to get to know him a bit and talk about possibly buying some more of his work.”10 Late home from the gallery that day, he arrived to find his wife Jane sitting alone with Hockney in the kitchen. “We were both rather shy,” she recalls, “and didn’t know what to say to each other. Our teacups were rattling in their saucers.”11 Kasmin’s first impression was of a rather gauche young man with National Health glasses and crew-cut hair, who was poorly dressed but clean, and spoke with a strong north country accent. Once they got talking and Hockney started to relax, he found him delightful, quickly warming to his open, trusting nature and wry sense of humour. They discussed his lack of money to buy canvas and paint, touched on the subject of what the Marlborough Gallery might be able to do for him, and arranged that Kasmin would look at more of Hockney’s work. He was left with a strong sense of a young artist destined to be a success.

Kasmin’s attempts to sell Hockney as a potential new star to Fischer, however, were a failure. Like most London galleries, the New London Gallery had a room for showing clients pictures that were not hanging up, complete with floor-to-ceiling grey velvet drapes on runners, an armchair, a sofa and an easel that could be lit from a spotlight. It was a style that might have been suited to showing off a van Gogh portrait or a Cezanne watercolour but for contemporary work it was the most inappropriate setting imaginable. Kasmin, however, persuaded Hockney to bring in some more of his pictures, and stored them behind the curtains. “Some were particularly scruffy,” he recalls, “painted on the cheapest canvas with ordinary white household paint, often unfinished, sometimes shaped with bits tacked on. Being so enthusiastic about them, I would have them out quite often, and Mr. Fischer would come in and say, ‘What is all this rubbish? I said you could have it here, but you were to keep it behind the curtains. Get rid of all this stuff!’ ”12 Apart from Kasmin, the only person at the Marlborough who liked the pictures was a fellow employee, James Kirkman, who would later buy several for only a few pounds.

*

If the critics were impressed by the work of the RCA students at the Young Contemporaries show, then their tutors were less so. “The faculty told us, in their own words,” Derek Boshier remembers, “to ‘stop all this pop art nonsense.’ They told us we had to take an old master or classical painting and do a painting based on it. We all thought this was a really boring idea, but in reality we got a lot out of it.”13 Derek chose a painting by William Blake, Elohim Creating Adam, which directly led to him using falling figures in his paintings, while Hockney chose Ford Maddox Brown’s The Last of England, which depicts the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner and his wife emigrating to Australia. Hockney’s version cleverly followed the exercise in hand without slavishly copying it, transcribing it into his own work, complete with coded numbers and letters and turning the figures of the man and woman into two men, their faces smudged in the style of Francis Bacon. His justification for this was that, in real life, no onlooker would ever see from a distance the faces in such razor-sharp detail as they appear in the original painting.

The moment that the RCA faculty ceased to dismiss Hockney’s work was when Richard Hamilton came to the Painting School and awarded him a prize. Often referred to as the father of pop art, the London-born Hamilton had trained at the Slade before joining the Independent Group and becoming a key figure at the ICA. Here he organised a number of influential exhibitions, such as The Wonder and the Horror of the Human Head, curated by Roland Penrose. In 1956 he was a major contributor to This Is Tomorrow, a landmark show at the Whitechapel Gallery, which featured a giant cut-out of Marilyn Monroe, Robbie the Robot from the film The Forbidden Planet and a jukebox; his poster for the show, a collage of 1950s American consumer culture titled Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? has become an iconic image. Hamilton was teaching in the interior design department of the Royal College when the painting students asked him to come and judge their sketch club. “He came and talked about the pictures,” wrote Hockney, “and gave out little prizes of two or three pounds. He gave a prize to Ron and a prize to me, and from that moment on the staff of the College never said a word to me about my work being awful … Richard had come along to the college and seen what people were really doing, and recognized it instantly as something interesting … Richard was quite a boost for students; we felt, oh, it is right what I’m doing, it is an interesting thing and I should do it.”14

Mark Berger continued to be an important influence on Hockney and encouraged him to further develop his burgeoning skill at etching. Berger had written a gay fairy tale, called Gretchen and the Snurl, for his boyfriend in New York. It told the story of an innocent young boy, Gretchen, who goes out into the world fortified only by a cake made by his mother, and meets an alien creature called Snurl. Together they are rescued from a fearsome monster with terrible teeth called the Snatch, which tries to engulf them both. “I think that in my mind David was Gretchen,” Berger remembers, “and Snurl was his boyfriend, and I showed it to David and he really liked it, so I asked him if he would do some illustrations. The interesting thing is that one of David’s best paintings came directly from the final etching in the story, which is a picture of the two boys hugging each other having been saved from what is really a monstrous vagina.”15 The painting to which he refers, and which was to become one of Hockney’s most iconic images, was called We Two Boys Together Clinging.

In his second year at the RCA Hockney was extraordinarily productive, creating a large body of work much of which was of an extremely personal nature. Many of the pictures feature two men embracing, and they manage to be both touching and funny. “Cheeky” is a word that Hockney often uses about himself and it could be said that it was barefaced cheek which enabled him to tackle such material, together with the use of humour. We Two Boys Together Clinging is a perfect example, though when Roger de Grey first saw it, his only comment was: “Well, I hope they don’t get any closer than that!”

The painting was inspired both by a press cutting and by a beautiful poem. On the wall close to where Hockney worked were a number of pin-ups of Cliff Richard, together with a newspaper clipping with the headline “TWO BOYS CLING TO CLIFF ALL NIGHT,” which told the story of a bank holiday mountaineering accident. Hockney’s quirky imagination naturally gave the story another interpretation; it also brought to his mind Walt Whitman’s poem “We Two Boys Together Clinging,” which has the lines:

We two boys together clinging,

One the other never leaving…

Arm’d and fearless—eating, drinking, sleeping, loving…

His painting, which was preceded by an experimental watercolour study, depicts two figures embracing, their bodies bound together by “tentacles” of desire emanating from both of them. In the bottom left-hand corner of the canvas, the numerals 4.2 link the painting to Doll Boy, while the figures are also identified by codes—the left-hand one, 4.8, being a self-portrait, while his partner on the right has both 3.18, for Cliff, and 16.3, for Peter Crutch, a student on whom Hockney had a huge crush. The word NEVER painted across the lips of the Hockney figure, however, hints at the inevitable unrequited passion, in the case of Peter Crutch because he was completely straight.

Peter Crutch with Peter C (illustration credit 4.2)

“David developed this incredible crush on Peter Crutch,” Berger recalls, “which was perplexing for him because he was still quite shy about his emotions.” Crutch was studying design in the furniture department, and had caught Hockney’s eye while in the college bar. “Oh! He’s just so beautiful,”16 Hockney had said to Berger, immediately besotted. They soon became friends and Hockney began to hang out with Crutch and his fashion-student girlfriend, Mo Ashley, who turned out to share Hockney’s love of Cliff Richard. Though Hockney kept his strong feelings of sexual desire strictly sublimated, he transferred them into a number of paintings, notably We Two Boys Together Clinging and The Most Beautiful Boy in the World. In the latter painting, which features a young man naked except for a “baby doll” nightie, made all the rage in 1956 by Carroll Baker in Elia Kazan’s film Baby Doll, he expresses his desire quite openly, using his usual code of numbers and graffiti. “I love wrestling,” he scrawls, and “come home with,” the inferred “me” hidden by a poster for Alka-Seltzer, which also presumably hides the word “love” at the end of “let’s all make,” which is written above a large red heart pushing against the boy’s head. The identity of the figure is made clear by the numbers 16.3 written just above his buttocks. Crutch, whose friendship with Hockney remained entirely platonic, was the subject of a number of pictures, including Cha-Cha-Cha that was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March, 1961 and Peter C, a portrait on a shaped canvas which was Hockney’s first since Portrait of My Father in 1955.

One rainy April morning, Hockney left the garden shed in which he was still living to make his usual journey to Exhibition Road and noticed a taxi dropping off a fare at the Kempsford Gardens boarding house. “I had a ten-shilling note in my pocket,” he remembers, “virtually my last ten shillings, and I thought, ‘It’s pouring with rain. I’ll get a taxi,’ which would have cost about five shillings to the Royal College, rather than 6d on the bus. Anyway I took this taxi, which left me with five shillings to my name, but I knew I could always live on my wits, and cadge a lunch here, a lift there. But that day I received a letter containing a cheque for £100 for winning a prize at some print exhibition, which I hadn’t even known about, and I thought, ‘This is fantastic. That taxi did it!’ ”17

The prize was for an etching which the head of the printing department, Alistair Grant, had discovered in the drying racks of the Print Room and had entered into an exhibition called The Graven Image at the St. George’s Gallery, Cork Street, where a young Cambridge graduate, the Hon. Robert Erskine, was spearheading a revival of English printmaking. He had persuaded the hotel group, Trust Houses Ltd., to donate prize money for the best five prints of the previous year, and Hockney had won for his print Three Kings and a Queen. For him the money seemed like a fortune.

More unexpected money came when the Royal College received a commission from the P&O shipping line, whose chairman, Donald Anderson, was the brother of the RCA’s provost, Sir Colin Anderson. Their new flagship, the SS Canberra, was being built at the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, and Hugh Casson, head of the School of Interior Design, was put in overall charge of this project. He brought in established artists such as Ruskin Spear, Edward Ardizzone, Humphrey Spender and Julian Trevelyan, while his senior tutor, John Wright, offered Hockney the job of decorating a room for teenagers, to be called “The Pop Inn.” “Julian and I decorated the staircase,” remembers Mary Fedden, wife of Trevelyan and one of Hockney’s tutors, “with cut-out metal figures of kings and queens. David decorated a room with an electric poker and most of it was writing, though there were also little pictures, all burnt onto the walls with this red-hot poker.”18

Living in a small hotel in Southampton, Hockney spent five days on this project, filling every inch of wall space with his characteristic graffiti, number codes and childish drawings, the cheeky side of his nature working overtime as he wondered what he might get away with. “Handsome milkman 21,” “Butch is naughty” and “Swing it Auntie” were three typical examples, while he paid homage to the current cool cigarette advertisement, “You’re never alone with a Strand,” with a drawing showing “Maisie” arm in arm with “Jack” and the words “You’re never alone in the Strand or Piccadilly.” “I finished the ‘mural’ on this ship,” he wrote to Berger. “I had a quite crazy ten days down there—the crew continually coming up to see me and watch. As I was working, a cabin boy came up and asked me to write his name up. I agreed and he told me it was ‘Jesse’…Ten minutes later he came back with all his mates (all aged about 16), all wanting their names up—‘Betty,’ ‘Judy,’ ‘Susan’ etc. All in a day’s work, eh?”19 Pathé Pictorial made a newsreel film about the Canberra’s maiden voyage in June 1961, which Hockney caught at the Forum cinema in the Fulham Road. “This is the Pop Inn,” said the veteran commentator, Bob Danvers-Walker, “a Rumpus Room for teenagers, where rock ’n’ roll has definitely replaced the sailor’s hornpipe.”20 Hockney’s idea that the teenagers would add to his graffiti with their own eventually came all too true, the majority of it, unfortunately, being better suited to a gents’ toilet, and the result was that the walls were boarded over and the Pop Inn became a camera shop.

Hockney was paid £100 for the Canberra mural. “With the money I’ll get,” he wrote to his parents, “I can have a cheap return air ticket to New York this summer—this is through the college, and I can stay with an ex-student there. I certainly seem to be getting around.”21 He had been offered a return ticket to New York for £40, and had jumped at it, having been under the impression that a ticket must cost at least a thousand pounds. He arranged to stay with Mark Berger, now back home. “The address I gave you for New York,” he wrote to his mother shortly before leaving, “will only be valid for the first fortnight—after that I will be travelling about, most likely down to New Orleans in the South and back through Texas and Oklahoma to New York … Tell John if I go to New Orleans, I’ll send him some postcards and maybe books from the home of jazz.”22

With the sale of pictures, the Erskine fee and the Canberra mural, Hockney had amassed about £300 by the time he left. “I thought I was absolutely in the money,” he remembers. He flew out on 9 July 1961, his twenty-fourth birthday, with Barrie Bates, another Royal College student, carrying with him, on the advice of Robert Erskine, a number of prints to show to the Museum of Modern Art.

Hockney had fantasised about New York ever since boyhood, when “New York Road” was displayed on the Leeds trams, and more recently, after looking at Mark Berger’s Physique Pictorial magazines, his fantasies had taken on a more sexual tone. The city did not disappoint him. “I was taken by the sheer energy of the place,” he recalls. “It was amazingly sexy, and unbelievably easy. People were much more open, and I felt completely free. The city was a total twenty-four-hour city. Greenwich Village was never closed, the bookshops were open all night so you could browse, the gay life was much more organised, and I thought, ‘This is the place for me.’ ”23 Berger was in hospital with hepatitis when Hockney arrived, but had arranged to come home to Long Beach in Nassau County, where he lived with his rather uptight father Benjamin, a pharmacist, and his glitzy stepmother Helen, who had big eyebrows, wore lots of jewellery and had once harboured ambitions to be an actress. “My father could not figure out David at all,” Berger remembers. “He enjoyed his company, but he just found him so offbeat in many ways. One of the things my father disliked was things being shifted from where they belonged. One day, for example, Hockney was told off for not putting the blueberries back in the refrigerator exactly where he had found them. Later he did a wonderful drawing based on this scene.”

It was not a match made in heaven, particularly because Hockney was still a radical pacifist vegetarian who was shocked by his host’s habit of going round the house killing ants with a spray gun. This oft-repeated scene was the inspiration for both a drawing of the spraying of the insects, and for a painting, The Cruel Elephant, which depicts an elephant treading on the words “crawling insects” and flattening them. Hockney almost fainted one day when Mark’s father returned home carrying a live lobster which he intended to cook for dinner. Helen Berger also had her differences with Hockney. “David didn’t care where he worked,” Berger recalls. “He would work anywhere where he was inspired. My parents had this really nice wall-to-wall white broadloom carpet and David loved to sit on the floor and draw with pen and ink or pencil. One day he was busy drawing when, plop, a big blob of ink dropped on the carpet. My stepmother nearly had a heart attack. ‘Look what David’s done,’ she wailed, ‘he’s messed up my carpet.’ I just said, ‘Look, Mother, cut it out and have him sign it and it’ll be worth couple of hundred thousand in a few years.’ David just laughed, but was so unique in his work and his personality that there was no question to me that one day he was going to be famous.”24

This was a view shared by William S. Lieberman, the legendary curator of the print department at the Museum of Modern Art. He was so impressed by the etchings that Hockney showed him, Kaisarion with All His Beauty and Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, both inspired by Cavafy poems, that he not only bought one of each for the museum, but sold all the rest of the edition on his behalf. Lieberman also sent him to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, one of America’s leading undergraduate art colleges, where Hockney set to work on a new etching, My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean, an expression of his continuing unrequited pining for Peter Crutch. “Dear All,” he wrote to his family on 19 July, “I’m having a fine time here, although the weather is very uncomfortable. (It seems to be always above 90°.) I will be staying in New York for quite a while now, as I am doing some work at the Pratt Institute here … New York is a rather confusing city as all the streets are absolutely straight—there are no curved ones—making it difficult to find your way about … The museums here (and there are many of them) are quite marvellous, and will take some time to absorb. Still I’ve plenty of time left.”25

This New York trip marked another significant moment: the dramatic transformation of Hockney’s appearance. A friend of Berger’s called Ferrill Amacker, “droll, very funny, quite camp and exotic” in Hockney’s words, came over to the Long Beach house one evening when Mr. and Mrs. Berger were out, and the three boys settled down to watch TV. When during one of the commercial breaks there was an advertisement for the hair dye Lady Clairol, with the catchphrase “Is it true blondes have more fun?,” Hockney became very animated. “This completely captivated David,” Berger recalls, “because to him the American image was butch football players and blondes, so he decided he was going to become blonde. We were all very excited and in the end all three of us went out and had our hair dyed. My father nearly had a fit when he came home and saw us all sitting there with our bleached hair.”26

With the $200 he made from the sale of his etchings Hockney bought himself a real American suit. He also moved in with Amacker, who lived in the Fruit Street area of New York in Brooklyn Heights, which was convenient for the Pratt Institute. “Ferrill had lived in New York for two or three years,” Hockney remembers. “He was young and had a bit of money, so he didn’t have to work. He had a proper little apartment with a television and a bathroom, things we certainly didn’t have in London. He was a bohemian and lived a marvellous bohemian life, and we became occasional lovers. People came and went in his apartment. I didn’t quite know who they were. People would get into the bed. It was just like that and I thought it was great. I thought, ‘This is the life.’ It’s a long way from Bradford, and London is dreary by comparison.”27

Hockney drank in everything about the city, staying up all night with Amacker, watching TV, cruising the gay bars, visiting Madison Square Gardens, exploring Harlem and the Bowery, taking part in an anti-nuclear march in Greenwich Village, and visiting all the museums and galleries. He was also thrilled to find plenty of fellow vegetarians, a discovery he enthused about in a letter to Ron Kitaj. “Ron Old Chap,” he wrote soon after his arrival, “I like this town—Vegetarian restaurants on every street corner. I haven’t been in the Empire State Building yet—but I wouldn’t be surprised if the whole of that wasn’t one big Veg restaurant. The funny thing is that New Yorkers don’t look like animal lovers.”28 It was 1961, and New York City seemed like the capital of the world.

When Hockney finally returned to London in early September, “with a yellow crew-cut, smoking cigars and wearing white shoes,”29 he was a different person. Donald Hamilton-Fraser, a landscape artist who taught one day a week at the Royal College, noticed that while previously he had come over as edgy and wanting to plough his own furrow, he was now more relaxed and had definitely found himself. He was also more energised than ever, his head swimming with “thousands of subjects.” Arriving a week before term started, he decided that his first painting was going to be really big, using a large stretcher, eleven feet by seven feet, which he had bought from a fellow student at the end of the summer term. While in New York, all the paintings he had seen had appeared enormous. Another good reason for painting a large picture was the purely selfish one that it would guarantee him a bigger working area in the studio, where people were already beginning to grab places. Among those who saw the work while it was in progress was Grey, 2nd Earl of Gowrie, a student at Balliol College, Oxford, who was brought along by David Bathurst, a former colleague of Kasmin’s at the Marlborough Gallery. “David took me one day to the Royal College of Art,” Gowrie remembers, “and there I saw this very interesting young man in wonderful clothes actually painting a practical joke, and the joke was, he told me, that all the other students were enamoured of large paintings, which was the result of the big backwash of Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still and people like that, so he thought he’d better shape up and do one himself, and I watched him paint A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Manner. It was a wonderful work, a very remarkable picture, and anyone could see that.”30

Once again, a poem by Cavafy, “Waiting for the Barbarians,” was the inspiration for this picture, the first painting of his final year at the RCA. In this, his first ever three-figure composition, he set out to paint a highly theatrical picture, using Egyptian tomb paintings as his stylistic source, depicting three officials—a clergyman, a soldier and an industrialist whose stiff and pompous outward appearance hides the truth that inside they are very small and ordinary. In its use of raw canvas rather than paint to provide background “colour,” it drew on influences ranging from Bacon and Kitaj to American painting. “This painting,” he wrote, “and the big works of 1961 … are the works where I became aware as an artist. Previous work was simply a student doing things.”31

While Hockney was in America, Kasmin had written to tell him that he had left the Marlborough Gallery and was dealing temporarily from home. The Hon. Sarah Drummond, the well-connected debutante who was the receptionist at the New London Gallery, had introduced him to a rich young man who wanted to invest in art, and Kasmin had gone into partnership with him. His name was Sheridan Blackwood, the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, a shy, diffident and immensely charming young man, with a penchant for fast and expensive cars, and one of the heirs to the Guinness fortune. Still a student at Oxford, where he inhabited a vast suite of rooms hung with good pictures in the Christ Church Quad, he dreamed of becoming a serious art collector. “He really wanted to be helped to get deeper into modern art,” Kasmin recalls. “I liked the idea of having someone around who would listen to what I liked and of having someone I could advise, and he liked the idea of being a collector and buying things at a good price.”32 Within a matter of months, Kasmin had told Dufferin that the time had come for him to strike out on his own. In the autumn of 1961, with the sum of £25,000 put up by Dufferin, they started Kasmin Ltd., and among the first artists they approached was David Hockney.

In spite of his recent successes, Hockney was still extremely short of money, and Kasmin decided to take him out for a business lunch to discuss some kind of contract. His years at the Marlborough had given him plenty of experience of expense-account entertaining, but he hadn’t accounted for Hockney being a vegetarian. “ ‘Lunch in the West End?’ said David. ‘Well, there’s a vegetarian place I like very much off Leicester Square called the Vega.’ Well, we went to this restaurant, and when I got the bill at the end it was something like one and ninepence. I couldn’t believe it. I was used to having a very good lunch at Wilton’s with a bill for two people for five quid. David saw me looking at the bill and said, ‘Oh, Mr. Kasmin, is it too much?’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘it’s certainly not, but it is very difficult to explain a bill like this to anybody.’ ”33

The result of the lunch was a contract forward-dated to when Hockney left college, it being illegal for a student to sign a financial contract. Since Kasmin didn’t want him to feel completely signed up, he generously excluded from it the territories of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in the Western Pacific.

The contract with Kasmin opened up a whole new world. “If you have someone who is keen on your work,” says Hockney, “you should follow them. It was exciting for me. He was incredibly energetic and I quickly noticed that he had a good eye, especially for drawings. He was an interesting man, very knowledgeable about pictures, and I was part of his eccentric taste. He used to have a kind of salon every Tuesday night, and this is where I began to meet interesting people. All kinds of people came, and I found myself meeting the art world for the first time.”34

Kasmin’s gatherings were open-house evenings of food, drink and conversation, and the occasional sale of pictures, which would be on show in the ground-floor rooms. These would be anything from traditional “bread and butter” works by Klee, Miró, Léger or Ben Nicholson, to newer work by Ellsworth Kelly, Allen Jones and David Hockney. Hockney drawings cost between £10 and £20 each, sold in these early days on a non-profit-making basis to give Hockney an income.

At the Royal College, people passing through could buy prints directly off Hockney for two or three pounds, with no edition number and often in a pretty grubby condition, sometimes with footprints clearly visible on them where they had been trodden on. There was no sense of things being valuable; they were after all just work in progress. Since his time at the Pratt Institute in New York, however, Hockney’s interest in printing had intensified as he began to discover its power as a means of expression. He put all of himself into these early prints, creating images of his inner life. He cast himself, for example, in the title role in a version of William Hogarth’s celebrated series of paintings and prints, The Rake’s Progress, in which he reimagined the follies of high and low life in eighteenth-century London as a tale of a young gay man trying to find his place in 1960s New York. Thus The Seven Stone Weakling, in America for the first time, visits gay bars and lives the high life until The Wallet Begins to Empty.

“One of the things that struck me in New York,” he remembers, “was that in the Bowery you did see bums on the street, which you didn’t see in London at that time, and of course that was perfect for The Rake’s Progress.” His original plan was to copy Hogarth and produce eight etchings, but when Robin Darwin got wind of this, he approached Hockney with a plan for the Royal College to produce a book of the work for its own imprint, the Lion and Unicorn Press. They would, however, require twenty-four prints. Hockney considered that this would mean padding the story out too much, as well as being far too big a task for a student working without an assistant, and so they compromised on sixteen, some of which would be based on the Hogarth original and some on his own experiences. “The Gospel Singing, with the Good People wearing ties with God is Love on them,” he recalls, “is based on a trip I made to Madison Square Gardens to hear Mahalia Jackson, and there was a choir jumping up and down singing ‘God is Love.’ It was amazing, pure Americana. The Door Opening for a Blonde was the Lady Clairol advert. Receiving the Inheritance was selling etchings to the Museum of Modern Art. Bedlam, right at the end, is when they’re all plugged into the first transistor radio. I’d seen these people with earplugs, and I thought they were hearing aids, like my father used to wear. In fact they were the first transistor radios, which you wouldn’t have got in England then. So it was a combination of things that happened to me.”35

That Hockney was making his mark in more ways than one is clear from a letter the RCA registrar, John Moon, sent to his old head at Bradford College of Art, Fred Coleclough. “I am sorry not to have written to you sooner about David Hockney,” he wrote. “He has become the College’s No. 1 Character, whose influence extends out beyond the Painting School, and his work and doings are watched by all up and coming students. He still spends most of his time painting, but he has done a number of very interesting etchings which have created a great deal of notice.”36 He went on to list a number of Hockney’s achievements: first prize in a student art competition organised by London University Union, a painting being selected for the Arts Council Collection; and three prints being chosen for the Graphic section of the Paris Biennale, suggesting that these “pretty solid and impressive” details should be passed on to the Lord Mayor of Bradford.

Hockney’s growing self-confidence meant that he was less reticent than the previous year about appearing in the 1961 Christmas Revue, and Ferrill Amacker, who was passing through London en route for Italy, persuaded him to do a drag act, in the dress that Janet Deuters had made for her striptease the previous year. “He managed to get David on stage,” Derek Boshier remembers, “wearing a frock and a pair of Yorkshire clogs, and he sang a song from Oklahoma!, ‘I’m Just a Girl Who Can’t Say No,’ changing the words to ‘I’m Just a Boy…,’ and it was the first time that a lot of people realised that he was gay.”37 Amacker was on his way to spend Christmas with Mark Berger, who was living in Florence on a Fulbright scholarship, and when the revue was over he persuaded Hockney to break the habit of a lifetime and accompany him to Italy rather than going home for Christmas. When Michael Kullman, the head of the general studies department, offered them both a lift as far as Switzerland in his little Morris van, they eagerly accepted and set off as soon as term was over.

This was Hockney’s first trip to Europe, made possible because his increasing income from painting meant he no longer had to rely on holiday jobs to get by. He was particularly looking forward to seeing the Alps, but because he had felt it only polite to offer Amacker the front seat, he was squashed in the back of the van, without windows, and saw virtually nothing of the landscape all the way to Berne. “It was Ferrill’s first visit to Europe,” he remembers, “and I was very amused by him referring to the toilets as the ‘restrooms,’ especially in France when they were just those holes in the ground. I thought, ‘I’m not sure you’d call that a restroom.’ It was a long journey and more than a little uncomfortable.”38 When they reached Berne, they bid farewell to Kullman, and took the train to Florence.

Hockney had imagined that Italy would be hot and sunny, but the reality was that the temperatures were below freezing. “It really snowed very heavily,” he wrote, “and the narrow streets of Florence with the snow on them were like a Dickensian London Christmas Card.”39

The trip was primarily an artistic one. Hockney slept on the floor of Mark’s studio in a sleeping bag and spent his days plodding round the city with his guidebooks, looking at galleries and ancient sites. He toured the Uffizi, loving the beauty of the medieval paintings while resisting any influences from them, though he did take in, from looking at a large Crucifixion by Duccio, that artists had been shaping canvases to suit their subjects for centuries. Evenings were spent with Berg and Amacker in the bars and cafes.

This trip became the basis for another delightful and funny autobiographical painting, Flight into Italy–Swiss Landscape, 1962. The fact that Hockney had seen nothing of the Swiss landscape was no barrier, as far as he was concerned, to painting a mountain picture. He would just make it up, incorporating a variety of influences of the time. Thus the main image is taken from a school geography book showing the contours of the mountains and their height, while peeking in from the back are some real mountain tops taken from a picture postcard. The unpainted canvas representing the sky has echoes of Bacon, the multicoloured lines delineating the mountaintops, of Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis. From the back of the Morris van charging across the canvas, with its three blurred and desperate-looking passengers and Hockney himself represented as a witch, come the words “That’s Switzerland that was,” a reference to a current advertising campaign by Shell.

Hockney painted two versions of this picture, the first of which, Swiss Landscape in a Scenic Style, was entered into the 1962 Young Contemporaries exhibition, one of four paintings he chose to demonstrate his versatility as an artist. On sending-in day he consolidated his friendship with Patrick Procktor, who was that year’s treasurer. “We started talking and we just became friends quickly. We simply had a lot of interests in common—painting, literature, and being gay, then. Because most people were in the closet at that time.”40 Patrick also rescued Hockney’s paintings from obscurity in the back room, insisting that they should all be hung together at the front. “Those four pictures I did,” he told the American painter Larry Rivers, in an interview published in the magazine Art and Literature, “were very concocted pictures. I deliberately set out to prove I could do four entirely different sorts of picture like Picasso.”41 The three other entries were A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the Semi-Egyptian Style, Tea Painting in an Illusionistic Style and Figure in a Flat Style, the last consisting of a canvas shaped like a figure, in which the base of the easel on which it sat became the legs of the figure. His choice of long titles for the pictures was by no means random and demonstrates his shrewdness. “By titling the pictures in this way,” he wrote, “in the catalogues there was more space between the lines, so it stood out. I knew all those tricks …”42

The 1962 Young Contemporaries show was an enormous success. “… if this year’s brilliant Young Contemporaries exhibition is any-thing to go by,” wrote the art critic of The Times, “then British Art is in for a healthy, lively period. The exhibition fairly bubbles with bright ideas and visual excitement.” He was impressed by the intelligence of the artists, and singled out “two markedly influential ‘art-school movements,’ the girder-and-iron-plate sculpture at St. Martin’s, and the raspberry-blowing ‘new-surrealist school’ (for want of a better name) at the Royal College of Art. This last dominates the first room, particularly in the person of its present star turn, David Hockney.”43 It is no exaggeration to say that this show, which was widely written about and discussed by the press, set Hockney on the road to fame.

The bright star that was the Young Contemporaries cast its light not just across London, but all over the country, thanks to a touring exhibition sent out by the Arts Council. For this a poster was commissioned from Hockney. “He produced an hilarious image,” said Mark Glazebrook, the Arts Council member who had come up with the idea, “of a scruffy youth being sick over a reproduction of the Leonardo Cartoon, the famous Da Vinci drawing that belonged to the Royal Academy. The Arts Council, out of the profits of its Picasso exhibition at the Tate, had donated a substantial sum to the Leonardo Appeal to save the cartoon for the nation, the Royal Academy being temporarily broke. My colleagues upstairs at 4 St. James’s Square, older, wiser and respected heads, were nervous of the effect of this Hockney image on ‘the provinces’—where David and I had both come from. I didn’t put up much of a fight and David didn’t kick up a fuss. We were forced to subtract the photo of the Leonardo which sadly left the youth just being sick over the blank piece of paper.”44

The exhibition inspired a multitude of ambitious, lively young people to head for the London art world. Among them was a charismatic young textiles student, Mo McDermott, who moved into a flat in Ladbroke Grove, Notting Hill, and found himself a job working for the interior designer Adam Pollock. Mo came from Salford, near Manchester, where he had attended the regional art school and gained a reputation for being both charming and mischievous. His father was away at sea, and he lived most of the time alone with his mother, with whom he had endless rows and who, disapproving both of the art school and his friends, would furiously trawl the local coffee bars looking for him. It was scarcely surprising that he couldn’t wait to get out of Manchester.

Mo quickly established himself at the centre of a lively scene revolving around the Elgin pub in Ladbroke Grove, which included his flatmates, two unknown young musicians, Rod Stewart and “Long” John Baldry, as well as two of his closest friends from Manchester, Ossie Clark and Celia Birtwell, both talented fashion students. At a party given by the Australian artist Brett Whiteley, who was in London on a travelling art scholarship, he was introduced to Hockney, whose work he already loved, and he almost immediately asked him for an etching. “Nobody had asked me for one before,” says Hockney, “and we quickly became friends. He was a little bit younger than me, very lively, very gay, very cocky, and confident. He was funny and he loved London, and moving in all different kinds of milieus. It was a far cry from Manchester.”45

At the time Hockney was desperately looking for a model for the life drawings he was expected to produce for his diploma. His problem was that he found the models provided by the college repulsive. “They really did have old fat women as models,” he wrote, “big tits hanging down; they sit on a chair and their ass goes falling over it … you couldn’t get further away from attractive flesh than this flesh. So I said, ‘Can’t you get some better models?’…but the idea of painting an attractive one they thought was rather wicked.”46 To make his point that all great painters of the nude have always painted models that they liked, he got hold of an American Physique magazine and copied the cover, in addition sticking onto the canvas one of his skeleton drawings as a reminder that he could draw something that was absolutely anatomically correct. To this he gave the title Life Painting for a Diploma. He then invited his new friend Mo to come in and model for him, and the college eventually agreed to pay him the set rate of £12 a week. Typically, Hockney did not do as he was asked, which was to produce a series of three different straight life paintings. Instead, he made one picture featuring Mo in three different poses and wrote “life painting for myself” across the top. When he left the painting on an easel overnight, somebody added the words “Don’t give up yet” at the bottom. “We never found out who did it,” Hockney recalled. “It’s still on the painting … I remember there was a girl opposite, a very, very quiet girl who’d never said a word, and I just couldn’t resist going over to her and saying, ‘How dare you write that?’ And I knew perfectly well that she hadn’t done it. But I laughed and so she saw the joke herself. I’m sure it was Ruskin Spear who wrote on it …”47

His teachers remained distinctly unamused, and the process of completing his diploma turned out to be rather less simple than his extraordinary talent would have suggested. There were other reasons for this, not least of which was the undercurrent of hostility that ran, barely hidden, among certain of the staff. “One of the sadder places I know,” wrote David Sylvester in the New Statesman in March 1962, “is an art school where the usual mistrust and envy between students and staff is engendered not by the students’ resentment of an established order which presents a solid barrier to their fame, but by the staff’s resentment that the students have more fame than they do.”48 Ann Martin, a painting student in the year above Hockney, remembers Carel Weight’s reaction when she showed him one of her abstract paintings for his opinion. “If I were you,” he said with barely controlled sarcasm, “I’d enter it for a competition. It’ll probably win a prize.”49

More serious was Hockney’s running battle with Michael Kullman over the general studies course, which required all students to attend a weekly lecture and produce a 6,000-word thesis in order to gain their diploma. Hockney considered it a complete waste of time. “I pointed out that there is no such thing as a ‘dumb artist,’ ” he recalls. “I was always against it because I thought that if anything was going to be compulsory it should be drawing, not this stuff. I never bothered going to the lectures, not even to sign myself in. I liked Michael Kullman, who was a bit of a mad philosopher, and I got to know him. I just didn’t approve of the system.”50

The result was that Hockney’s hurriedly written thesis on Fauvism was not considered acceptable. “Dear Hockney,” wrote the registrar on 11 April 1962, “You will have noticed from the Results Lists which have been posted on the School’s notice board that you have failed the Final Examination in General Studies which means that irrespective of the result of your professional work you will not be eligible for the award of the College Diploma at the Convocation Ceremony to be held on 12th July.”51 The letter went on to say that if he was prepared to carry out additional work and be re-examined, then it would be possible for him to gain the diploma if the new work was considered satisfactory. Hockney, however, was cocky and confident enough not to care, especially since he now had a dealer. “In a way I was set up professionally even before the diploma show,” he remembers, “so when they were going on about diplomas, I thought, ‘Well, Kasmin isn’t asking to see a diploma.’ I thought, ‘Why bother about all this in painting of all things?’ It just seemed ridiculous. I was confident enough to just simply laugh at it.”52 With characteristic wit and self-assurance, his response to the whole episode was to design his own diploma in the form of a coloured etching depicting, beneath the coat of arms of the college, a seated Robin Darwin holding up a two-faced Michael Kullman. The image is contained within a frame which rests upon the backs of five tiny figures, representing Hockney and four other failed students, bent double beneath its weight, bowing in shame.

When Hockney went home for a few days at Easter, his mother confided to her diary, “He looks well, but I’m not keen on his blond hair.”53 He gave her a cheque for £20 to buy a new sewing machine, the first of his own money that he was able to give her, and the two of them trailed round the Bradford shops in search of a new machine, to no avail as she was unable to make up her mind. “Met Mrs. Todd who was pleased to see David but not keen on the blond hair.”54 When they got home, he filled her in on his plans. “I think he will do very well when he leaves College in July,” she wrote later, “—already has made quite a name for himself. He is to make a 3 years contract with ‘London Art Dealers’ who will pay him a monthly salary—but who also have first preference to buy his pictures. He hopes to have a one-man exhibition at Geneva, Switzerland in 6 months’ time.”55 His mother’s pride was not necessarily shared by the neighbours, however. “I remember … I was walking down the street,” Hockney recalled, “and I overheard one of the neighbours saying to another, ‘Oo, look, ’e’s back again, and ’is brothers did so well, you know.’ Idle Jack back from London. It’s just, I suppose, what little people are like, who live little, ordered, quiet lives …”56

The Diploma, 1962 (illustration credit 4.3)

The diploma fiasco ended in an episode that did not reflect well on the Royal College. It was quite clear to Robin Darwin that, since Hockney was undoubtedly one of the best students they had had for decades, he should be awarded their gold medal, a rare accolade. Much to his horror, he then discovered that this was not possible for a student who had failed the general studies course, so he made it quite clear to the Examinations Board that a sub-committee should be appointed, consisting of himself, Carel Weight and Michael Kullman, to re-examine the results and come up with new ones. This they did, coming to the conclusion that, for some inexplicable reason they must have miscounted the original marks. The committee “therefore ruled that all the results be set aside and that all the students, including David Hockney, be adjudged to have passed the examination.”57 No one was convinced by this “recount” story, which cast a poor light on all the participants, and rankled with Hockney for years after.

The award of the gold medal attracted wider attention for Hockney, and the fashionable men’s magazine Town dispatched one of its star young reporters, Emma Yorke, to interview him. By now he had moved from the shed into a basement flat in Lancaster Road, Notting Hill Gate, or Rotting Hill Gate as it was then nicknamed by some. It was a tiny premises shared with a fellow painting student, Mike McLeod, that consisted of a bedroom with two beds, a small room off it containing a Baby Belling cooker and an outside toilet. They hung their socks out of the window to eliminate their smell, and at the bottom of the steps, in the well, was a small wall with soil in the top of it, which Hockney had attempted to cheer up by planting it with the plastic flowers that came free in packets of Tide washing powder.

“David Hockney is twenty-five years old,” wrote Emma Yorke, “and has just been awarded the Gold medal at the RCA for his painting … His hair is an improbable buttercup yellow and his heavy spectacles give an air of ridiculous seriousness to his face—he looks in fact distinctly like the characters in his paintings which have a quality reminiscent of Dubuffet. ‘I have my melancholic days mind you,’ he said, but looks imperturbable—then a flash of pleasure comes across his face. ‘I wish I could dye the whole of Bond Street blond, every man, woman and child. I don’t really prefer blond people but I love dyeing hair.’ His hair glints in the sun like a newly thatched cottage … This odd Harpo-Marxist swivels his rainbow body in the chair…‘I’ve got to go to Cecil Gee’s now to buy a gold lamé coat. I’m going to wear it when they present me with the gold medal.’ ”58

Bradford, 1962 (illustration credit 4.4)

In the end Hockney was proud to receive the medal, if only for the sake of his parents. “David rang up on Friday evening,” wrote Laura in her diary on 6 July, “to tell us he is being given a GOLD MEDAL & has a First CLASS HONOURS. He is so unconcerned—but it is a wonderful honour & he has evidently been persuaded to attend the ceremony, which previously he had no intention of doing. We are very proud of him & would like to go to London to see the ceremony & share the honours. I’m so glad David is still humble—but he has earned the prize. His only love is to paint, so far.”59

The convocation ceremony, at which various outstanding individuals in the world of the arts had honorary awards and titles conferred upon them, took place annually in the hall of the Royal College of Music, and was attended by all the college students, as well as graduates, family and friends. It was an event that engen-dered some nervousness among the staff, as it was traditionally the occasion for elaborate practical jokes. “When I was awarded my diploma,” Roddy Maude-Roxby recalls, “I organised placards with the words APPLAUSE, LAUGHTER and SILENCE written on them, which the graduates, who were sitting behind the principal and staff on a raked platform, hid under their gowns, only to produce them at the most inappropriate moments possible.”60 On another occasion, at a signal, the graduates all donned heavy-rimmed glasses and moustaches and imitated in unison the gestures of the principal, while perhaps the most outrageous stunt was when the Duke of Edinburgh was giving a lecture on the importance of “Artist-engineers,” and as he took his place on the rostrum, every single student and graduate released a red plastic toy helicopter which rose in unison to the ceiling.

Hockney, watched by his proud parents, shared his day with the distinguished critic and poet Sir Herbert Read, the architect of Coventry Cathedral, Sir Basil Spence, and the designer of the Mini, Alex Issigonis, all of whom were being awarded fellowships. When it came to his turn to be awarded the gold medal for work of outstanding distinction, he went up to collect it, to deafening applause, resplendent in the gold lamé jacket as well as the traditional and requisite academic gown. “David looked fine,” wrote Laura in her diary, “in his gold lamé jacket, and gold-banded black gown and cap—his white (gold) hair to match. The Principal in his speech said that under Hockney’s eccentricities his heart was in his work, & that not only was he honoured by the College, but would he thought be one day an honour to his country. I’m glad David is humble enough not to care too much about the presentation, but realizes that his work alone will get him a place in the world.”61 Laura also recognised that she was witnessing the end of an era and the beginning of a new one: her words were tinged with both pride and regret. “Oh for the happy days,” she wrote, “when we all had such fun at home together. We shall never see those days again, but the memory is a tonic.”62