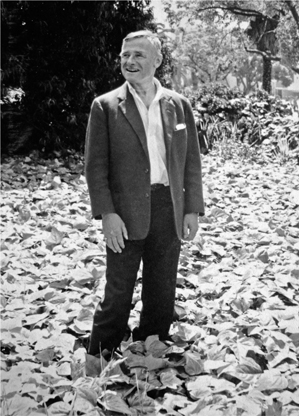

Christopher Isherwood (illustration credit 6.1)

In the autumn of 1963, Hockney had begun an affair with Ossie Clark, Mo McDermott’s friend from Manchester, that was to have huge significance in his life. Extroverted and charismatic, Clark exuded confidence. He was just into his second year and starting to blossom under the tutelage of the brilliant professor Janey Ironside, head of fashion design at the Royal College of Art. Clark had been a precocious stylist even back in Manchester, which in those days was provincial compared to London. “He wore flares he’d made himself and 13-inch winklepickers, a trilby hat and a long black ex-army coat; his hair was dyed black, meticulously cut short in the fashion of the day,” remembers Jane Normanton, a fellow student at the time, who recalls thinking, “ ‘Wow, you can do that in London, but not here! He was determined to go places.’ ”1

Though he was quite openly gay, Clark was in a relationship with Celia Birtwell, who had followed McDermott down from Manchester and was working as a waitress in the Hades coffee bar. Theirs was a friendship which, stimulated by a shared interest in fashion and design, as well as by a certain physical attraction, had drifted into an affair, and they were living together in Notting Hill, in a tiny flat above a bicycle shop on Westbourne Grove. When Clark met Hockney, however, the combination of his sexuality, charm and seeming innocence, not to mention his star being in the ascendant, was too much, and Clark was immediately seduced.

“Taken up seriously by DH,” Clark noted in his diary for 1963. “He was giddy, effeminate, mad and exaggerated,” Hockney recalls, “and I liked the personality immediately. He didn’t have a northern accent because he’d taken elocution lessons.” They were young, free from their parents, ambitious and keen to try out new experiences. “Mo used to organise sexy evenings at Powis Terrace. We enjoyed playing around, we enjoyed sex. When it came to sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll, everybody was at it, though I was never into rock ’n’ roll. Sex and drugs certainly. It was a potent combination.”2

When Hockney embarked on the longed-for U.S. trip at the end of December, flying first to New York, Clark agreed that he would visit during the college holidays. Hockney stayed with Mark Berger and visited the Pratt Institute where he completed and sold two etchings, Edward Lear and Jungle Boy, the latter, which portrays a very hairy man under a palm tree staring at a large snake, being inspired by Mark who was extremely hirsute and kept snakes as pets. These earned him a princely sum, $2,000, good pocket money for his trip to LA. He also visited the New York dealer Charles Alan, who had seen Hockney’s work at the Kasmin Gallery, and was keen to give him a show at his gallery on Madison Avenue. It was agreed that Hockney would exhibit pictures from his California trip in the autumn.

As they discussed the next stage of the trip, Alan discovered how limited Hockney’s knowledge of Los Angeles was. In fact, he was so worried when he found out that not only did Hockney not know a soul in LA, but that he couldn’t drive either, that he tried to persuade him to go to San Francisco instead. But Hockney was adamant he was going to LA. Part of its glamorous appeal was sex, or the perceived availability of it, not just the perfect bodies he had yearned after through the pages of Physique Pictorial, but the sleazy, homoerotic side as portrayed in John Rechy’s City of Night, his novel of hustlers in New York, Los Angeles and New Orleans. It is easy to understand from the vivid LA section how exciting it must have made the city seem to a relatively innocent young man eager to widen his experiences. “This is clip street, hustle street—frenzied-nightactivity street: the moving back and forth against the walls; smoking, peering anxiously to spot the bulls before they spot you; the rushing in and out of Wally’s and Harry’s: long crowded malehustling bars.”3

As Hockney was leaving the gallery, Alan said, “But if you don’t drive, how on earth are you going to get into the city?” When Hockney replied, “I’ll just catch a bus,” Alan realised how clueless he was about the place, with its hundreds of square miles of suburbs, and contacted one of his artists, an LA-based sculptor called Oliver Andrews, to ask if he would meet Hockney at the airport.

Approaching Los Angeles airport Hockney became more and more excited. “I remember flying in on an afternoon, and as we flew in over Los Angeles I looked down to see blue swimming pools all over, and I realised that a swimming pool in England would have been a luxury, whereas here they are not, because of the climate. Because you can use it all the year round, even cheap apartment blocks have pools.”4 Oliver Andrews was waiting for him in his Ford pickup truck, and drove him to the Tumble Inn, a small motel at the bottom of Santa Monica Canyon. “David immediately sent a telegram back to Charles Alan,” Andrews later wrote, “telling him he had safely arrived, and said ‘Venice California more beautiful than Venice Italy.’ ”5

Hockney was even more thrilled arriving in LA than he had been on his first trip to New York. “I was so excited,” he wrote. “I think it was partly a sexual fascination and attraction … I checked into this motel and walked on the beach and I was looking for the town; couldn’t see it. And I saw some lights and I thought, that must be it. I walked two miles and when I got there all it was was a big gas station, so brightly lit I’d thought it was the city. So I walked back and thought, what am I going to do?”6 The solution came to him in a flash—a bicycle—so when Andrews came round the next day to check on him, they went off to a cycle store.

Since the only knowledge Hockney had of Los Angeles was derived from City of Night, he decided to visit Pershing Square to try and experience first hand the sleazy, sexy, hot nightlife so evocatively described by Rechy, the world of “the nervous fugitives from Times Square, Market Street SF, the French Quarter—masculine hustlers looking for lonely fruits to score from … the scattered junkies, the small-time pushers, the queens, the sad panhandlers, the lonely exiled nymphs haunting the entrance to the men’s head, the fruits with the hungry eyes and jingling coins; the tough teenage chicks—‘dittybops’—making it with the lost hustlers … all amid the incongruous piped music and the flowers-twin fountains gushing rainbow colored: the world of Lonely America squeezed into Pershing Square …”7 Checking on a map, Hockney saw that Wilshire Boulevard ran from close to the Tumble Inn, ending a few blocks from Pershing Square, so he jumped on his new bike. There were two things, however, he had failed to take into account. The first was the distance, which was nearly seventeen miles, and the second was the fact that the real Pershing Square might be different from that described in the novel.

“I started cycling,” he later wrote. “I got to Pershing Square and it was deserted; about nine in the evening, just got dark, not a soul there. I thought, where is everybody? I had a glass of beer and thought, it’s going to take me an hour or more to get back; so I just cycled back and I thought, this just won’t do, this bicycle is useless.”8 When Oliver came round the following morning, religiously keeping up his promise to keep an eye on Alan’s protégé, he was lost for words when Hockney told him he had cycled to Pershing Square. Nobody ever went to downtown LA, he told him, and suggested to Hockney that they should go out and buy him a car. The fact that he couldn’t drive would not be a barrier, he promised, as he would give him some lessons. As for the licence, obtaining one in California was easy.

Over the next few days Oliver gave Hockney some instruction in his pickup truck, before taking him off to get a licence. This procedure consisted of filling in a form and answering a simple written test, with questions like “What is the speed limit in California?” whose multiple-choice answers required little more than common sense to answer correctly. In the driving test, when they asked him where his car was, he pointed to the truck. The instructor, who by now thought he was quite mad, drove around with him for an hour or so, failed him on four points, but awarded him a provisional licence anyway. “How easily I got it terrified me actually,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘So this is all they do here to get one?’ I mean, in England they deliberately fail a lot of people. In the end I just thought, ‘Well, that’s the kind of place it is.’ ”9 With plenty of money in his pocket, Oliver then took him to buy a car, and for $1,000 dollars Hockney became the owner of a white Ford Falcon with a bright red stripe down the sides.

He now set out to practise on the local roads, heeding Oliver’s one piece of advice, which was “Avoid the freeways.” Needless to say, on his second day behind the wheel he found himself on a freeway by mistake, an experience that both thrilled and frightened him. “Once I got on,” he remembers, “I didn’t know how to get off it, so I just kept going, and the sign said San Bernadino, and then Las Vegas, another 250 miles, and I thought I might as well just drive through the desert. It would be good practice and it would give me confidence. So I drove to Las Vegas. I even went to the casino there and won some money, about $80, on my first trip to a casino.” Travelling back on the old road through the desert, he passed through the Mojave Desert city of Barstow, and when he stopped for gas they gave him canvas bags full of water in case the car overheated. “Of course I loved all that,” he recalls. “I felt it was like the Sahara I was crossing.”10

Finding a studio and somewhere to live in LA was not difficult in those days. Taking the advice of Oliver Andrews and of Bill Brice, another artist Charles Alan introduced him to, he just drove around looking at “For Rent” signs, and soon found rooms for $90 a month in a Santa Monica apartment house which looked like the superstructure of a 1930s ocean liner, as well as a studio on Main Street in Venice, overlooking the ocean, for $80. Within spitting distance he also discovered a small shop that sold some imported foods, including Marmite and his favourite cereal, Weetabix. When he asked for bloater paste, however, he was told they did not import it since it was not considered fit for human consumption. “Within a week of arriving … in this strange big city, not knowing a soul,” he noted, “I’d passed the driving test, bought a car, driven to Las Vegas and won some money, got myself a studio, started painting all in a week. And I thought: it’s just how I imagined it would be.”11

One day a week, usually on a Monday, he would take out his car and cruise the big wide boulevards of LA, just to look at what was around him. He was endlessly thrilled by what he saw and took inspiration from everything—palm trees, banks, squares and avenues, office blocks, not to mention the weird and wonderful variety of domestic architecture, the Spanish haciendas, the mock-Tudor villas, the castellated mansions, the Swiss chalets, all sitting alongside futuristic buildings like John Lautner’s Garcia House on Mulholland Drive, or his Chemosphere on Torreyson. “Los Angeles is the only place in the world,” he says, “where the buildings actually make you smile when you drive around.”12

“There were no paintings of Los Angeles,” he told Melvyn Bragg, in an interview in the Listener in 1975. “People then didn’t even know what it looked like. And when I was there they were still finishing some of the big freeways. I remember seeing, within the first week, a ramp of a freeway going up into the air, and at first it looked like a ruin and I suddenly thought, ‘My God, this place needs its Piranesi; Los Angeles could have a Piranesi, so here I am!’ ”13 So, rather than his own ideas or things he’d seen in a book, Hockney began to paint the things he saw around him.

The first picture Hockney painted in Los Angeles, Plastic Trees Plus City Hall, shows a large palm tree in front of a cloudy sky with the City Hall skyscraper in the background. It was also the first painting in which he successfully used acrylic paint. This was a medium he had tried once before, back in London, but had abandoned because the textures and colours of the paints he could get hold of were not very good. Finding only American equipment in an LA art store, however, he discovered that their acrylic paints were vastly superior and started to use them. “It was what a lot of the American artists were using,” he remembers. “It is different from oil paint because it dries very quickly, and you have to paint in certain ways with it.”14 Other characteristics of acrylic, such as its regular consistency, allowing it to be applied thinly while retaining its full brilliance of colour, go a long way to explaining the changes in Hockney’s painting style during this period. His paintings became flatter and much more about image and colour than about texture. “When you use simple and bold colours,” he later wrote, “acrylic is a fine medium; the colours are very intense and they stay intense …”15

Until arriving in LA, Hockney had been quite ignorant about the existence of a Californian art scene. Yet he had happened on a golden age in LA, a period when art was all about art and artists, not institutions and money.

There was a thriving scene based in and around La Cienega Boulevard, where Felix Landau, given the title of the “Tastemaker of La Cienega” by the LA Times, had opened his gallery in 1951 to show established greats like Rico Lebrun and Jack Zajac; his was the first Los Angeles gallery to show Francis Bacon. Landau eschewed pop art, leaving that to galleries such as the Rolf Nelson, and the Ferus, the latter where Irving Blum had given Andy Warhol his first solo exhibition, and his first exhibition of the Soup Cans, and among whose leading representatives were Billy Al Bengston, Ed Kienholz and Larry Bell, the self-styled “Studs” who would saunter into Barney’s Beanery, a bar at the top of the street, as if they were members of some Hell’s Angels gang.

The Beanery was the premier LA art-world hangout, as much for the fact that Barney was willing to carry a tab as for its prime location so close to all the galleries. It was dimly lit, the drinks were cheap, the bartenders friendly, and it adjoined an inexpensive diner where artists could afford to eat. It became so popular that in 1965 Ed Kienholz turned it into a work of art, a tableau called The Beanery, which, when you looked into it, gave you the odour of beer, and the sound of clinking glasses and bar-room chatter from an audiotape.

La Cienega Boulevard was also the scene of an LA cultural imperative: the Monday Night Art Walk. This was a tradition that had begun in 1961 when two dealers decided to hold simultaneous openings in the hope of attracting bigger crowds. Other galleries soon joined them, until it became a regular occurrence. “Monday night on La Cienega,” wrote the correspondent for Time magazine in July 1963, “is quite possibly not only the best free show in town but also one of the most popular institutions in Los Angeles County … Last week the 22 exhibitions ran the gamut of modernism, from a show of Arp and Henry Moore sculpture at the distinguished Felix Landau Gallery to paintings by pop artist Billy Al Bengston at the Ferus Gallery.”16 There was op art at the Feingarten Gallery, kinetic art at the Esther Robles Gallery, and if it was the weird and wonderful you were after then you needed to go no further than Cecil Hedrick and Jerry Jerome’s Ceeje Gallery, which showed the work of the renegades and mavericks.

“On a Monday I would go to La Cienega,” Hockney recalls, “and I would walk up and down and I would tell them I was a young artist from England, and like that I got to know artists quickly.”

He soon added Ed Ruscha, one of Irving Blum’s young stars, to his list of new friends. Another friendship he struck up at this time was with Christopher Isherwood, the writer whose Berlin Stories had so intrigued him, and to whom the poet Stephen Spender had given him an introduction. Isherwood had emigrated to the United States at the outbreak of the Second World War, where he had lived happily in California, first with the photographer Bill Caskey, and latterly with the artist Don Bachardy. Bachardy was thirty years younger than Isherwood and had such youthful looks that when they set up home together in 1953, when Bachardy was eighteen, the rumour went round that Isherwood had taken up with a twelve-year-old. In many ways the success of their relationship lay in the father-and-son aspect of it, and Isherwood actively encouraged Bachardy to go to art school to study painting seriously, and was immensely proud when he became successful.

Hockney had found out that the house in which Isherwood lived, 145 Adelaide Drive, was just up the hill from the Tumble Inn. “Stephen Spender had bought etchings off me in 1961,” Hockney remembers, “and he certainly had written to Christopher Isherwood, because he knew that I was coming to LA. So I phoned him up and he simply invited me over for dinner.”17 Bachardy was away so Isherwood, slightly panicked at the idea of having to entertain a complete stranger on his own, rang his close friend Jack Larson, a screenwriter, librettist and actor, and asked him and his lover, the writer and director Jim Bridges, to come over and join them. “David arrived on a bicycle,” Larson remembers, “with this portfolio of drawings from A Rake’s Progress. The work was extraordinary and unlike anything I’d ever seen, and I could see immediately how talented he was. Frank O’Hara used to take me around places and explain in a lucid and dynamic way why Jackson Pollock was extraordinary, or why Kline was extraordinary and it turned out that he was almost right about everything, whether it was poetry and literature or painting. I learned from him to look at something and trust my judgement, and right away I saw that these drawings of the Rake’s Progress were real, and that David was the real thing, original and interesting. They looked like something that could have been on the wall of a pharaoh.”18

Christopher Isherwood (illustration credit 6.1)

Isherwood hit it off with Hockney straight away, initially for the simple reason that he fell in love with the way he spoke. “Chris called me up,” Bachardy remembers, “and told me that he’d met this quite extraordinary young Englishman with bleached blond hair and glasses with a wonderful Yorkshire accent that he fell for immediately because it was the same accent that he would have had if he hadn’t been sent off to public school.”19 Isherwood had been born at Wyberslegh Hall, on the borders of Cheshire and Greater Manchester, where he spent much of his childhood, before being sent off to prep school in Surrey, and then to Repton in Derbyshire. Even after years of living in America, he still had strong feelings of nostalgia for his childhood: meeting Hockney brought back a whiff of home.

A week later, Bachardy also met and immediately liked Hockney. “He was so easy to get to know,” he recalls, “and he and Chris had already established a friendship. And I saw straight away that he was inner-directed. He was a young man with a purpose.”20 Initially a little in awe of Isherwood, Hockney soon relaxed around him and found common ground in their love of reading and literature: it was the beginning of what was to be one of the key friendships of his life. As Isherwood was to tell him later on, “Oh David, we’ve so much in common: we love California, we love American boys, and we’re from the North of England.”21

Scarcely had Hockney settled into his new life than Kasmin arrived from London, another Los Angeles virgin, now looking to his young client to show him the ropes. “David had found me a room in a place which he thought was very swanky called ‘Gene Autry’s Hotel Continental,’ ” Kasmin remembers. “It was on Sunset, very close to Schwab’s Coffee House, where girls used to go for coffee and hope to be picked up by casting directors. David lived in a rented room in Santa Monica, and he decided he would come and share the room with me. To his amazement I had no idea who Gene Autry was, and so it seemed to him a waste that I should be staying there.”22 One thing about the hotel that puzzled Hockney was the fact that the elevators were always filled with serious-looking men in dark suits, a mystery solved when they discovered that the hotel was the business headquarters for the local branch of the Mafia. Any qualms Hockney may have had about the discovery of this piece of information were, however, made up for by the swimming pool on the roof, where he spent many happy hours tanning himself.

Ever since he had arrived in LA, Hockney had been planning to pay a visit to the offices of AMG, the Athletic Model Guild, the publisher of Physique Pictorial. He was intrigued by the fact that though many of the storylines were set indoors, in a bathroom for example, there was often the strong shadow of a palm tree across the bath, suggesting that the pictures were in fact shot outside. He both wanted to see where this happened and buy some of the photographs, so he took Kasmin to the studios, which were on downtown 11th Street in a house which the founder of the AMG, a photographer called Bob Mizer, shared with his mother. The city jail, situated close by, provided quite a few of the models for the magazine, in the way of drunken sailors and similar types who were in the can overnight, while the rest were usually young men who were killing time while searching for the Hollywood Dream. It was their way of earning a quick ten bucks.

“We went down to a suburban backstreet,” Kasmin remembers, “to an innocent-looking house in nowhere-land, and pressed a bell on a door in a sort of privet hedge, and we were let in. David told them he’d come from England and that he was an admirer of the magazine. We found ourselves in a perfectly ordinary house, which had a lean-to in the back garden near a pool.”23

Surrounding the “tacky” swimming pool were a series of Holly-wood ancient-Greek plaster statues, and the lean-to constituted the studio where they would create the shower, bathroom or living room which they needed for their shoots. There were notices everywhere warning people not to touch anything, because Mizer knew that as soon as they weren’t being watched, the models would steal every-thing and run off. “The studio only had two walls,” Kasmin recalls, “so they could move the camera around, and this was where his idea of paradise was created, where the boys stood taking their showers. We both thought it was hilarious and were amazed at the roughness of it all, and the fact that you could make glossy dreams out of such shabby bits of plywood, while they were astonished at the idea of anyone wanting to come to their offices.”24 Mizer’s answer to anyone who criticised the quality of the sets was to say, “Remember we are AMG, not MGM.”25

The photographs which Hockney bought on that first visit to AMG were the inspiration for a series of voyeuristic paintings featuring showers, the first of which was Boy About to Take a Shower, based on a shot of a fourteen-year-old boy, Earl Deane, which had appeared in the April 1961 issue. Standing in a shower cubicle, he is handling the spray with water cascading down his back. The painting omits both his head, which is visible in the photograph, and the water, while emphasising the shower head and the lines of his naked body, creating an overtly sexual image. The shower paintings which followed this, Man in Shower in Beverly Hills and Man Taking Shower, both made much use of the water. “Americans take showers all the time,” Hockney says. “I knew that from experience and physique magazines … Beverly Hills houses seemed full of showers of all shapes and sizes—with clear glass doors, with frosted glass doors, with transparent curtains, with semi-transparent curtains … The idea of painting moving water in a very slow and careful manner was, and still is, very appealing to me.”26

When Hockney returned to London at the end of the year and was asked by Richard Hamilton to give a lecture at the ICA, he chose the subject of gay imagery in America, basing his talk around Physique Pictorial. With enormous glee he regaled his audience with his account of visiting the AMG studio, showing slides from the magazine alongside clips from soft-porn movies with titles like Leave My Ball Alone, in which a Greek statue comes to life and indulges in a bout of nude wrestling with a young boy who has stolen his ball. While delivering a thought-provoking lecture, he also had the audience in stitches with his witty and mischievous comments on the contrived scenarios.

The gay scene in LA may still have been underground, but to Hockney it certainly seemed more accessible. “Nowadays people are used to an organised gay scene,” he says, “but in those days things were very different, and it was only here that I found a scene that did not exist elsewhere. I suppose I was like a child in a sweet shop. The California beach was like heaven. The boys are very good-looking and they look after their bodies.”27 He admits to having been thoroughly promiscuous for the first and only time in his life. “I used to go to the bars in Los Angeles and pick up somebody. Half the time they didn’t turn you on, or you didn’t turn them on, or something like that. And the way people in Los Angeles went on about numbers!”28 One drawing from this period, Two Figures by Bed with Cushions, brilliantly evokes the urgency of such sexual liaisons, showing two men apparently hurriedly undressing in preparation for an encounter of which, after it was over, as Hockney later recalled, the only memory would be the appearance of the bed. Kasmin, a somewhat unwilling companion on these trips to gay bars, often had to be protected from unwanted attention by Hockney saying that he was his date and dragging him onto the dance floor. “Neither of us were very great dancers,” he recalls, “and Californians are all so big. On one occasion David took me to a bar, and they refused to give me a beer because I didn’t have my passport on me and they thought I was underage. I was David’s dealer aged twenty-eight, and David said, ‘Oh, don’t worry! Just give my young friend a glass of milk. He’ll be quite happy.’ ”29

The true reason that Kasmin had come to LA was to further spread the word about Hockney among serious collectors. Meeting people was never a difficulty for Hockney, because they almost always loved him as soon as they met him. He was open and funny and, particularly to the Americans, he was exotic. They loved his clothes and his accent. Likewise, he thought Americans were hilarious, as well as being thrilled to meet actors he had admired since he was a boy, such as Vincent Price, who invited him and Kasmin for a drink at his home, where he had a library built into a disused swimming pool and served them cocktails from a coffin-shaped cabinet.

Most important were collectors such as Betty Asher, the daughter of a wealthy pharmacist, who had been collecting contemporary art since the late fifties and owned important works by Rauschenberg, Warhol, Ruscha and Lichtenstein; and Betty Freeman, who had trained as a concert pianist and who collected abstract expressionist paintings and was a patron to many composers. It was Jack Larson who introduced them to Betty Freeman. “He told me he’d got this new friend,” Kasmin recalls, “who was avant-garde. ‘The stuff on her lawn looks like grass,’ he said, ‘but it’s more like watercress.’ ”30

California Art Collector, which was based on these and other meetings, was the second painting completed by Hockney in LA, and included domestic imagery common to the type of collector he had visited. Since all the houses had big comfortable armchairs, the collector, a woman, is seated in one, on a big fluffy carpet, admiring a sculpture by the Scottish artist Bill Turnbull, then sculptor of choice to the nouveau riche. A striped painting, possibly by Morris Louis, hangs on a pink wall; there is a primitive stone head, while outside there are palm trees, a view of the Santa Monica Mountains—and, most significantly of all, a swimming pool, the first to appear in Hockney’s paintings.

*

Though Hockney had begun Man in Shower in Beverly Hills in Santa Monica, it was actually completed in Iowa City, where, in the summer of 1964, he was offered a six-week job teaching at the University of Iowa, in the heart of the Midwest. The invitation came from Byron Burford, the dean of the university art department, and a painter himself. Never having experienced the American interior, Hockney accepted the post eagerly, and a salary of $1,500. He took the painting off its stretcher, rolled it up, put it in the boot of his car and, deciding to go via Chicago, set off on Route 66. “I drove through Arizona, New Mexico, Kansas, Missouri and Illinois,” he remembers, “picking up hitchhikers all the way. The freeway wasn’t done, so I took the old road. I drove on my own and I stayed in Chicago for five days and looked at the big museums and things, and then drove west to Iowa City.”31 All the while he was nervous about what was in store on his first major teaching post, not just because of what was expected of him, but because of his appearance. Somehow he didn’t feel he looked serious enough. Somewhere en route, he happened to pass an optician’s with a pair of heavy round horn-rimmed spectacles in the window, which he decided were just what was needed to give him a more professorial look. He ditched his National Health spectacles, and wearing his new “owl” pair, he drove confidently into Iowa City, and straight through it from one end to the other, in the mistaken belief that he was just passing through its suburbs.

Iowa was a real culture shock for Hockney. He found it stiflingly dull. The landscape was boring and flat, with mile after mile of identical houses stretching into the distant skyline, and the only occasional excitement was to be found in the form of huge electrical storms and massive fast-moving cloud formations. The faculty was very conservative, and when he took his first drawing class he was shocked to find that most of those attending were doing so not out of a desire to learn to draw, but because they got paid more money as a teacher if they were known to have attended this particular class. “There were three nuns in the class,” he remembers, “and I thought that maybe they were in it for the drawing, but no, it was the same thing. They wanted to get money from teaching.”32

One advantage of the lack of a social life in this small city—there was one bar he liked, but it was as much a bohemian hangout as a gay bar—was that Hockney devoted almost all his spare time to painting. He completed Man in Shower in Beverly Hills, and four other pictures, The Actor, Arizona, Cubist Boy with Colourful Tree and Iowa, a landscape, depicting farm buildings beneath a dramatic cloudscape, to remind him of a place he had little intention of returning to. His routine was to paint at night, and then go swimming in the local pools, which didn’t close till two in the morning. “… perhaps it was three or four till I got to bed,” he told Cecil Beaton, “so I couldn’t get up at eight o’clock, so I’d go in at ten thirty and stay till one, but no one seemed to care.” Because none of the students could paint a sphere, he set his class to paint a door. “They all got canvases the size of a door and painted as realistically as possible, and we had an exhibition of all the doors down a corridor. It looked nice.”33 When Patrick Procktor came to teach in Iowa the following year, Hockney recalls, “he found out that they didn’t consider me as having been too respectable. He was much more willing to spend evenings with the art history faculty after hours. I didn’t really care. I think Patrick was a little more polite than me, and he did tell me later that they wouldn’t employ me there again.”34

When the six weeks were over, Hockney had the paintings all shipped to Charles Alan’s gallery in New York, and set off to meet Ossie Clark in Chicago, the plan being that they would drive together to New Orleans. It turned out to be the beginning of an epic road trip. Clark had won a competition for shoe design and had used the £150 prize money to fly first to New York, where, on a night out on the tiles, he had met Brian Epstein, the manager of the Beatles. “Introduced to Eppie in a gay bar …” he wrote in his diary. “… going down in a lift with BE.” When Clark told him he was heading west to meet Hockney, Epstein had given him a note which he had promised would get them access to the Beatles’ upcoming concert at the Hollywood Bowl in LA. Later that evening, Clark was refused a beer at PJ Clarke’s, as the barman thought he was underage. “ ‘What’s a beer please?’ (I’D AVOID EYE CONTACT.) ‘Alright, you’ve caught me out, I’ll have milk,’ ” and someone took a dislike to his long hair. “ ‘Fucking long-haired faggot! Listen buddy, this is a tough town and if I were you I’d leave.’ ”35

He flew to Chicago to meet Hockney, who was under the impression they were heading for New Orleans. “No, we’re going to California to see the Beatles,” said Clark. “I realised,” Hockney remembers, “that as Ossie couldn’t drive, I would be doing all the driving, and it’s a very long way, about two thousand miles. I remember saying to him, ‘Well, we’ll have to drive long, long hours, so can you keep me entertained?’ In those days you couldn’t pick up that much music on the radio. It was mostly apple pie recipes and things like that so I asked him to make up gossip, anything to keep me awake, which he did for the most part, though there was one moment driving through Nevada when I fell asleep and we ran off the road. Well, we got there and then I found out that he didn’t have tickets, just this note, and I thought, ‘This is the Hollywood Bowl. Will we get in?’ ” Epstein’s note worked: they did get in, and saw the Beatles in style. “We were sitting in the front row, and it was terrific.”36

Derek Boshier was living in San Francisco at the time, and after the show, Hockney called him and asked if he would like to join the trip, to which Boshier readily agreed. While they waited for him to arrive, Hockney showed Clark the sights. “Disneyland,” Clark noted in his diary; “mistaken for a Beatle on a trip to the moon to escape the excitement of the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. Bette Davis in the flesh; Mrs. Dennis Hopper; Beach Boys, Surf City; art hype; The Tumble Inn Motel, Santa Monica; Hard Days Night—6 no 1 hits, The Beatles.”37

Three days later, the trio set off, their first stop being the Grand Canyon, where Hockney did a tiny drawing in a notebook, Ossie and Derek in Grand Canyon, which he gave to Boshier. In 1964, the U.S. counterculture hadn’t spread much beyond the big cities, so both Clark and Hockney had to put up with ridicule throughout the 1,300-mile drive, particularly in the more redneck areas. This was especially true of Clark. “I remember that wherever we went,” says Hockney, “whenever we sat down in a restaurant, everyone thought Ossie was a woman, because he had long hair, and nobody had long hair in those days. None of us really cared when they made fun of us. We thought it was quite amusing and we gave up on it.”38 Clark also had a penchant for wearing crushed-velvet coats and chiffon scarves, and in the Neiman Marcus store in Houston, where the gang had stopped to buy mirrors which looked like the front cover of Time magazine, the assistant who served them said she didn’t need their addresses to ship the mirrors: “Don’t worry, I’ll just send them to Camelot.”

As they drove through the Deep South, they saw another side of life in America. “We passed through terrible areas of rural poverty,” Boshier recalls, “and it was very noticeable that all the blacks we saw had their heads bowed.” When they finally got close to New Orleans, and passed the sign welcoming them to the city, they did what had become routine, which was to switch on the radio to the local station so that they would get the music of the area. “So we turned the radio on when we saw the New Orleans sign,” Boshier remembers, “and the first song that came on, which had just been released that very week, was the Animals singing ‘There is a house in New Orleans,’ the opening lines of Bob Dylan’s ‘House of the Rising Sun.’ I’ll never forget that. The New Orleans sign was there and the record was playing, and I thought that was great.” Here Boshier decided it was time to part company. “I said to the others I was going to go off and find some girls, and I was going to leave them to do whatever they wanted.”39

After a short stay with Ferrill Amacker in New Orleans, Hockney and Clark drove to New York, where Hockney had his first American show at the Alan Gallery, selling all the paintings he had completed in Los Angeles as well as Iowa, Arizona and Cubist Boy with Colourful Tree, which were painted in Iowa. Clark, on a permanent high, was thrilled to meet Paul Newman, Diana Vreeland, then editor of American Vogue, and Andy Warhol at the opening. He also hung out with the band of the moment, the Velvet Underground, got an appointment with John Kloss, one of the hottest young designers in New York, and met the artist Robert Indiana, who gave him a bolt of cloth printed with his own op art design, which he was to use to great effect in his degree show the following summer.

Hockney used the time to consolidate his friendship with Henry Geldzahler, who took him round the galleries and amused him with tales of his various adventures, which had included starring in one of Warhol’s films, in which he had to sit on a sofa in the Factory smoking a cigar and staring at the camera for hours while Andy busied himself making phone calls, occasionally returning to check that the camera was still running.

Yet despite the excitements of the trip, when Hockney and Clark finally returned to London in early October, they were barely speaking. “I think he found David very difficult to be with all the time,” Celia Birtwell recalls. “I think he didn’t like the fact that the trip was very much on David’s terms. He had won £150, and that was all the money he had, so after that ran out he really had to do what he was told.”40 He called Birtwell and begged her to come back to him, telling her how much he had missed her and how tired he was of the lifestyle he had been leading. Within a few weeks he had moved in to the flat she was renting in St. Quintin Avenue, where they were to enjoy their happiest months together. Hockney returned to Powis Terrace, which he set about smartening up in expectation of an imminent visit from his parents, whom he had not seen for nine months.

Kenneth and Laura Hockney had two reasons to visit London in November 1964: firstly to meet Margaret, off the boat from Australia, where she had been visiting Philip, who had emigrated there. Secondly, Ken had a demonstration to attend. “We found David’s flat beautifully decorated,” wrote Laura in her diary on 12 November; “unfortunately heater not fixed in lounge—but kitchen was complete and warm.” Over the next few days, while awaiting Margaret’s arrival, she filled her time shopping in the Portobello Road, visiting the Commonwealth Institute, attending the Lord Mayor’s Show and engaging in her customary maternal tasks. “After meal, gathered up David’s washing & took to launderette—what a wash! Guess he’s been so busy decorating, no time to launder.”41

When Ken and Laura departed to met Margaret at Tilbury Docks, Hockney got back to work in his Powis Terrace studio on a picture that would remind him of what he was missing. It was Picture of a Hollywood Swimming Pool, and was based on drawings that he had done on his return to California after Iowa, when he had become fascinated by the squiggly lines created by the reflections of water in swimming pools and the problems of how to paint water. “It is a formal problem to represent water,” he wrote, “to describe water, because it can be anything—it can be any colour, it’s moveable, it has no set visual description. I just used my drawings for these paintings, and my head invented.”42 He was happy to admit that in these first paintings of water, when struggling to work out the best way to depict it, he was influenced by some of the later work of Dubuffet, and by what he referred to as Bernard Cohen’s “Spaghetti Paintings,” such as Fable and Alonging. This influence is also clearly seen in another pool painting, California, with its squiggles and jigsaw-like shapes.

While his fascination with swimming pools was to become a major theme of Hockney’s work, at this very moment he was temporarily distracted by a niggling anxiety that his work might not be considered sufficiently contemporary. Though this was partly just the insecurity of the young, it was also boosted by the fact that he only had to look at Kasmin’s other artists, such as Kenneth Noland, Frank Stella, Jules Olitski and Anthony Caro, to see that he was the only figurative artist in the stable. “I have never thought my painting advanced,” he commented, “but in 1964 I still consciously wanted to be involved, if only peripherally, with modernism.”43 So he fleetingly flirted with abstraction, beginning with Different Kinds of Water Pouring into a Swimming Pool, Santa Monica and following on with a series of still lifes, such as Blue Interior and Two Still Lifes and Portrait Surrounded by Artistic Devices, in which he explored the different possible interpretations of Cezanne’s famous remark that he wanted to “treat nature by the sphere, the cylinder, the cone.” “The ‘artistic devices,’ ” Hockney wrote, “are images and elements of my own and other artists’ work and ideas of the time … All these paintings were, in a way, influenced by American abstractionists, particularly Kenneth Noland, whom I’d got to know through Kasmin who was showing him. I was trying to take note of these paintings. The still lifes were started with the abstraction in mind, and they’re all done the same way as Kenneth Noland’s, stained acrylic paint on raw cotton duck, and things like that.”44

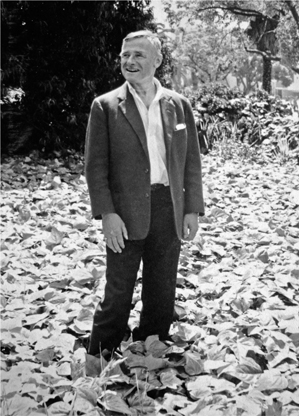

A second series of still lifes, titled A Realistic Still Life, A More Realistic Still Life and A Less Realistic Still Life, was completed in Boulder, Colorado, in the summer of 1965, where Hockney had been invited to teach at the university. He flew first to New York, accompanied by Patrick Procktor, who was fresh from his second one-man show at the Redfern Gallery and on his way to follow in Hockney’s footsteps teaching in Iowa. Patrick was a flamboyant figure, an eighteenth-century dandy transported into the twentieth century. Born in Dublin, the son of an accountant for Anglo-Iranian Oil, he chose to do his national service in the navy, where he learned to speak Russian. He eventually graduated to becoming a Russian interpreter with the British Council, in which post he was quite happy to indulge the fantasies of those of his friends who thought he was a spy. Openly homosexual and a talented artist, who studied at the Slade under the landscape painter Kyffin Williams, he was immensely tall, with gangly legs, a long sensitive face, expressive hands and slim fingers which he used to eloquent purpose, and a sharp fantastical wit. Hockney had found him stimulating company since they first met at the Young Contemporaries show in 1962. They were part of the same bohemian circle, and Procktor was the occasional lover of Michael Upton, now married to Hockney’s great friend Anne McKechnie. “The thing that I loved about Patrick was his flamboyance,” Hockney remembers. “I also liked him because he could mock the art world. He felt he was a bit more outside it than I was, and anybody who mocks pomposity I’m attracted to.”45

It was Patrick’s first trip to New York, which he initially hated. “It seemed hideously ugly, hard and rude,” he later wrote, “and their art was repulsive to me … Apart from looking at art, David and I rushed through a lot of low life, downtown.”46 They stayed with Mark Berger in his apartment in the Bowery, a loft with enormous rooms to paint in, and Hockney gave Procktor a four-day whirlwind tour, visiting all the museums, meeting artists and eating out a lot—they were constantly hungry as Mark had nothing in his refrigerator but macrobiotic food. Hockney sold some etchings to the Museum of Modern Art and used the money to buy another car, a plum-and-cream Oldsmobile Starfire convertible with polychrome metallic plum upholstery, the Falcon having been ditched the previous autumn. “It was about six or seven years old,” Hockney remembers, “an enormous car with a seven-litre engine. It did about twelve miles to the gallon, but since gas was only thirty cents a gallon then, that didn’t matter, and it had an electric roof and electric windows, which in 1965 was very rare.”47 “It was rather an outrageous car,” wrote Procktor, “and got some stares by the time we reached rural Iowa where we were asked, ‘Why are you driving that flash nigra car?’ ”48

Patrick Procktor (illustration credit 6.2)

After dropping Procktor off in Iowa City, Hockney made his way to Boulder, which turned out to be a much bigger and livelier place than Iowa. The university, founded at the same time as the state of Colorado in 1876, had a spectacular setting against the background of the Flatirons, a range of impressive rock formations which run along the eastern slope of Green Mountain, with the Rockies rearing up behind. Though the faculty had given him a large studio in which to work, to Hockney’s amusement it had no windows, something that immediately reminded him of his trip to Italy with Michael Kullman, trapped in the back of a van. “Here I am surrounded by these beautiful Rocky Mountains,” he recalled, “I go into the studio—no window! And all I need is a couple of little windows.”49 His typically witty response was to paint Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians, a picture entirely invented from geological magazines and his own romantic ideas, there being no Indians within three hundred miles of Boulder. The plastic and metal chair in the painting was put in for compositional reasons, and, to explain its presence, he dubbed the Indians “tired.”

Hockney enjoyed his time in Colorado. He found himself a lover, a nineteen-year-old American student called Dale Chisman, who, after a car accident, was lucky enough to have been exempted from the Vietnam draft. This dark cloud hung over all male students of eligible age in 1965, a year in which the number of ground troops deployed to Vietnam rose dramatically from 3,500 to 200,000. “Dale became a friend because he was lively,” Hockney remembers, “and anyone who was lively was someone you hooked up with. Students like Dale made the place, so I would be hanging out with them outside the college.”50 His friend Norman Stevens came to stay, and there was also a visit from another of Kasmin’s artists, Colin Self, who was in the U.S. on a painting trip. When Procktor’s residency in Iowa was over, he too drove over to Boulder, with his own student lover, Dick Mountain, whose ambition was to go to San Francisco and become a drag queen. They spent a few days in Boulder, exploring the Rockies, where Hockney gave Dick the nickname “Pike’s Peak” after one of the higher mountains, and driving up to Central City, an old gold-mining town near Aspen. At the end of the trip, all five, together with Dale Chisman, piled into the Oldsmobile, which had bench seats, making for plenty of room, and drove to San Francisco, a thrilling journey taking in mountainous twisting roads, broad highways and numerous motels. When they reached San Francisco they stayed at the Embarcadero YMCA, which was cheap, if not to the taste of Stevens and Self, who found it much too gay.

After a few days enjoying the sights of San Francisco and its gay bars, Hockney and Procktor left the others and drove down to LA, where Procktor had to fulfil a commission from Joan Cohn, the wealthy widow of Harry Cohn, former head of Columbia Pictures, to paint a mural for the cinema in her home in Beverly Hills. This had come about through his friendship with her lover and soon-to-be husband, the actor Laurence Harvey, star of such films as Room at the Top, Walk on the Wild Side and The Manchurian Candidate. Harvey was a bisexual who strung along his long-term lover and manager, James Woolf, through three career marriages, and once confessed to Jack Larson that he considered women to be “extortionate creatures.” He had befriended Procktor the previous year while he was appearing onstage in London in Camelot at the Drury Lane Theatre, and had bought some of his paintings from the Redfern Gallery. Patrick was suitably impressed. “Laurence Harvey was at the height of his fame,” he wrote, “and a darling.”51

To begin with they stayed at the Tumble Inn, where they were eventually joined by Stevens and Self, who stayed for a few days, dining with Isherwood and Bachardy, going to see Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl and hanging out at the beach. “We didn’t have that much money but it was all very exciting,” Hockney recalls. “I remember we were on this beach in Santa Monica, just up by Santa Monica Canyon. It was a high school beach, and there was this very pretty California girl lying on the sand. Colin was looking at her and he told me that she had inspired him for a work he was going to do called ‘Nuclear Victim.’ I couldn’t see the connection. Anyway, he did her as a shrivelled-up corpse.”52 Eventually Stevens and Self took the Greyhound bus back to New York, leaving Hockney and Procktor to move into a guest house which Joan Cohn had lent them in the grounds of her home. Hockney immediately nicknamed it the “Little Grey Home in the West.” Soon after their arrival there, they were invited up to dinner in the main house, where they enjoyed a real Hollywood evening. “The dining room looked wonderful: the waiter wore white gloves, the knives and forks and even the dishes were gold,” Procktor recalled. “The food was hamburgers. Joan smiled and said she hoped we thought that this was typically American, and she added that the steak had been flown in from Maine. After dinner they played a gramophone record of Larry’s, where he read love poetry over a romantic orchestral accompaniment, for an hour. They were so very much in love.”53

While Procktor was working on his painting, Hockney was approached by Ken Tyler, a printmaker, who had his own atelier, Gemini Ltd., on Melrose Avenue. Tyler had attended the Art Institute of Chicago, and studied lithography at the John Herron School of Art in Indiana, graduating with a master’s degree in 1963 and then studying with the French master printer Marcel Durassier, who had worked with both Picasso and Miró. He opened Gemini in 1965 and his strong emphasis on the importance of technique soon began to attract many of the greats of the American art scene, such as Josef Albers, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. His approach to Hockney was for a series of lithographs with a Los Angeles theme. The only problem was a lack of finance, as his backer had just pulled out leaving him high and dry. Hockney, who had immediately liked Tyler and been greatly impressed by the quality of his work, called Paul Cornwall-Jones in London and had little difficulty in persuading him to agree to pay for and publish the edition.

What Hockney came up with was a typical example of his subversive wit, a set of six prints that poked fun at the kind of Beverly Hills collectors who bought art either for social prestige or financial investment. He called it A Hollywood Collection and it was his idea of an instant art collection, pre-packaged for a Hollywood starlet, and because Gemini was situated behind a framer’s shop, he drew appropriate frames as part of the prints. Each lithograph is an imitation of a framed picture representing a particular genre. The titles speak for themselves: Picture of a Still Life that has an Elaborate Silver Frame, Picture of a Landscape in an Elaborate Gold Frame, Picture of a Portrait in a Silver Frame, Picture of Melrose Avenue in an Ornate Gold Frame, Picture of a Simply Framed Traditional Nude Drawing and Picture of a Pointless Abstraction Framed under Glass. Once again his versatility and his fertile imagination triumphed.

Hockney encouraged Procktor to come up and have a look at Gemini, resulting in him producing his first lithograph, Seated Crowd on the Grass, featuring portraits of himself, Hockney and Rolf Nelson, whose gallery on Santa Monica Boulevard was at the cutting edge of the avant-garde. He also introduced him to Barney’s Beanery, and to his friends Ed Ruscha and Dennis Hopper. When Joan Cohn and Laurence Harvey left on a trip to Europe, Procktor had to move out of the guest house, so Hockney arranged for them both to stay at Jack Larson’s. With A Hollywood Collection finished and delivered to Gemini, he was preparing to return to London for his second show with Kasmin, when he got involved in a fateful distraction. Hanging out in his favourite gay bar, the Red Raven, he was introduced to a boy called Bob, known locally as “Princess Bob.”

“Ten days before leaving for London,” Hockney remembers, “I met this kid who I thought was Mister California Dish. His name was Bobby Earles and I said I was just going back to England, why not come back with me? He was an incredibly sexy boy. He was everything that California was about. But the thing is, it was simply lust on my part, and lust doesn’t work for too long.”54

That night he told Procktor that he was in love, and that he was taking Bob back to England with him. This beautiful blond Californian boy, Hockney’s perfect fantasy made real, had never left California before, so the first thing they had to do was get him a passport. Then the three of them drove to New York, with Procktor and Hockney arguing all the way. “He said, ‘You’ve gone mad,’ ” wrote Hockney, “ ‘you’re crazy.’ I said, ‘Never mind, we’ll make up for it at night, it’s all right.’ ”55 When they reached New York, Earles thought it was a terrible place, but Hockney told him that he was going to love Europe. Leaving Procktor to get to know New York a little better, they boarded the liner SS France, the flagship of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, to sail to Southampton. With an interior designed and built by the finest French craftsmen and artists, and eighty chefs on board, giving its Grill Room the reputation of being the best French restaurant in the world, the France was the fastest and most luxurious ship afloat. All this was wasted on Princess Bob, however, who only wanted to sleep and have sex, a memory of which was beautifully captured in the patently erotic post-coital study Bob, France 1965.

In a postcard to Mo McDermott from LA in early October, Hockney had written, “I will be back in London about noon on November 1 at Waterloo Station from the S.S. France. I am bringing back a marvellous work of art, called Bob.”56 So McDermott, Kasmin, Clark and a few others knew what to expect when they formed a welcome-home committee at Waterloo early that morning, a meeting that was captured on camera by the film director Henry Herbert, who was shooting a film about Kasmin for the BBC.

Unsurprisingly, Earles was less than impressed with London. He thought Powis Terrace was a “dump,” bemoaned the fact that there were no gay bars, and showed no interest in anything other than having sex, and wanting to meet the Beatles and the Queen. “He’s a dumb blonde bleached whore,” said Clark, who gave him the nickname “Miss Boots.”57 The only thing that excited Earles in the ten days he spent in London was sitting at a table next to Ringo Starr at the Scotch of St. James’s nightclub. “He was very dumb,” wrote Hockney. “He’d no interest in anything … After a week I said I think you should go back … And I put him on a plane and sent him back. There is a drawing … of a marvellous pink bottom, and that’s all he had in his favour I suppose.”58 The story of Princess Bob did not end happily. Hockney saw him two years later working as a go-go dancer on Laguna Beach, and a few years after that, he heard that he had died from a drug overdose.

Hockney’s second show at the Kasmin Gallery opened in December 1965, with the title Pictures with Frames and Still-Life Pictures, the prints being shown simultaneously at Alecto Editions. There was the usual opening party attended by the cream of society, and this time enlivened by the arrival of Sheridan Dufferin’s flamboyant mother, Maureen, Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, and her third husband, Judge John Maude, a notoriously old-fashioned and right-wing judge. “He was famously anti-homosexual,” Kasmin recalls, “and was always sentencing gay people to hard labour. There was a lot of activity going on in the back room, boys kissing all over the place and people smoking dope, and he came up to me and asked, ‘Those people down there, aren’t they homosexuals?’ He was in a state of some nervous interest at watching all the forbidden actions going on.”59

The show was a sell-out, the average price for Hockney’s work having risen to £500, with the largest canvas in the exhibition, Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians, going for £750 to the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation.

The critics were unanimous in their praise. “Most of David Hockney’s latest paintings … are the outcome of a trip to California,” wrote John Russell in The Times. “They are certainly among his best so far.”60 Writing in the London Magazine, Robert Hughes noted that “Hockney’s art has lost its exotic heroes. The magicians, generals, hot-gospellers and Ku Kluxers of his earlier paintings have now disappeared; what fascinates him is the face of Los Angeles, which he paints … as a flat, glaring, overlit, antiseptic madhouse in which nothing happens.”61 In Studio International, Edward Lucie-Smith wrote: “The paintings, drawings and prints in the new exhibition are the product of a much longer residence in and around Los Angeles, and are a great commitment to America itself. By comparing them to Hockney’s earlier work, it is possible to see how astonishingly sensitive he is to atmosphere. Chameleon-like, he has become a Californian …”62

Robert Melville, in the New Statesman, pinpointed the swimming-pool painting as being of particular merit. “The best picture in the exhibition is about the best he has ever done. Called Two Men in a Pool, LA, it depicts two sun-bronzed figures with pale bottoms at the far end of a rippling, sunlit pool that is treated as an intricate curvilinear pattern in blue and white, and it is far and away the most imaginative and pictorial use to which Art Nouveau has been put since its revival. I doubt if any artist of his generation has produced a better picture.”63

Once again Hockney waited till after the opening was over to invite his parents to see the show. They arrived on Laura’s birthday, 10 December. “I had asked David on the phone,” she wrote in her diary, “to have his place clean—& it was—but I had a lovely surprise, on turning bed covers down to find new sheets and new blankets. Now! I said it feels like home & hugged him. They were tomato red sheets and p. cases—& next morning David asked if I would like some for my birthday—well of course—so off we went to Barkers & I was presented with two sets.”64 Laura was happy to be introduced to “many artist friends,” who included Patrick Procktor, Michael Upton, Peter Blake and his wife Jan Haworth, and Dale Chisman, who had come over from Colorado, and the show filled her with pride. “I think David’s exhibition was very pleasing & very wonderful,” she wrote, “—some of the drawings I could understand & more so after reading the many write-ups in several papers. I’m glad it is a success—there were many people there when we went. He has done very well indeed.”65 Her joy at having him back in England was, however, to be short-lived.