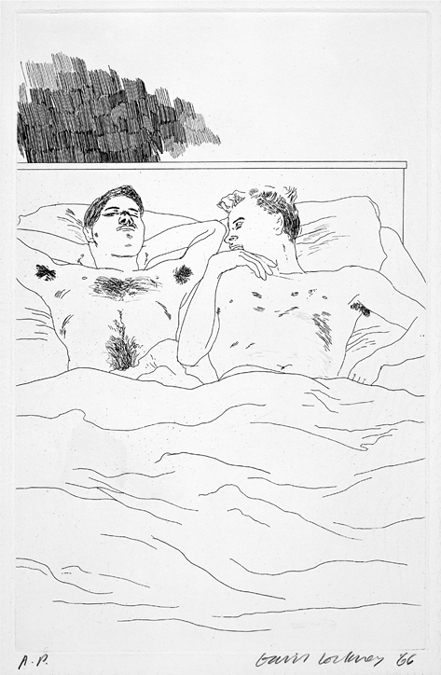

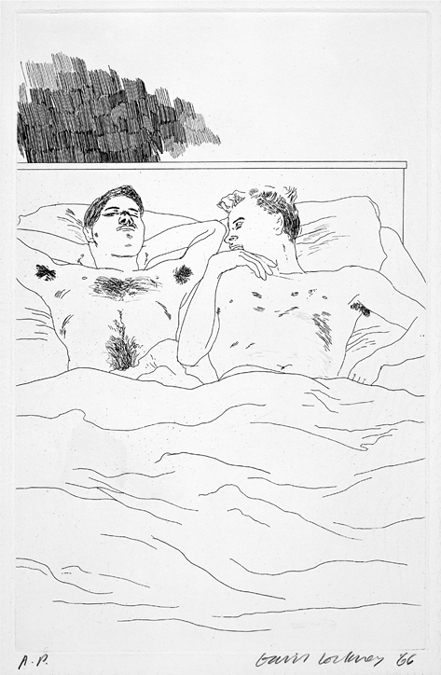

In the Dull Village, 1966–67 (illustration credit 7.1)

In the Dull Village, 1966–67 (illustration credit 7.1)

“POP ARTIST POPS OFF” ran the headline in the Atticus column in the Sunday Times on 9 January 1966, followed by the story that “David Hockney, Britain’s brightest young artist, has decided to leave Britain.” It described him wandering around his flat deciding whether or not to sound off about his feelings in a letter to the Daily Mirror.

I want to know why the Government is trying to get everybody into bed by eleven o’clock. Why else do all the pubs close at eleven and the telly shuts down at twelve? It makes me fed up, so I’m going to America. Life should be more exciting, but all they have is regulations stopping you from doing anything. I used to think London was exciting. It is compared to Bradford. But compared with New York or San Francisco it’s nothing. I’m going in April. I’m going to teach for two months in Los Angeles, then I’ll just stay on and paint. I’ll come back now and again to see my dealer and my parents, but I doubt if I’ll ever stay here again. I feel more lively there so I work better. That’s all it is.1

That Hockney’s outwardly sunny nature concealed a streak of rebellious anger did not come as a surprise to his mother, though she confessed to having been “rather shocked” by this outburst when she read it. “I know it is the side of David we do not see,” she wrote, “but he does not hide it. So different from our way of life. I should like to talk with him about it.”2 In spite of the fact that he was living in a period when class barriers were beginning to break down among the young, when fashion designers and pop stars, photographers and artists, largely from the working class, were mixing freely with the upper and middle classes, dining with lords and ladies and partying with royalty, Hockney felt a strong solidarity with his working-class roots. He was angry for the workers. “It’s … to do with the class system; it’s still to do with the fact … that drinking after eleven costs more because you have to join a club,” he wrote. “The poor workers, they’re supposed to go to bed and get up to work. It’s very undemocratic.”3

It was this sense of righteous indignation that Hockney put to good use when it came to propaganda on behalf of gay rights. In September 1957, Sir John Wolfenden’s famous report had recommended that homosexual behaviour between two consenting adults should no longer be considered a crime, a suggestion that had earned it the nickname the “Pansy’s Charter” from the Daily Express. Yet the Macmillan government had chosen to ignore its advice, despite a plea in a letter to The Times signed by thirty-three eminent public figures from the worlds of politics, the Church and the arts, including Lord Attlee, J. B. Priestley, Bertrand Russell, the Bishops of Birmingham and Exeter, and Stephen Spender, that the government should “introduce legislation to give effect to the proposed reform at an early date.”4 Even Hugh Gaitskell, leader of the Labour Party, and Harold Wilson, the man who was to succeed him, were nervous of supporting the Wolfenden Committee’s recommendations, believing that to do so would cost them six million votes. They may have had a point. When a proposal was made in Burnley, Lancashire, that the town should allow the opening of a club for homosexuals, a leading Labour activist commented, “There’ll be no buggers club in Burnley.”5 On the whole in 1966, public attitudes to homosexuality were still largely hostile, and sex between men was illegal and punishable with a prison sentence, which made David’s openness about his sexuality all the more courageous. He just didn’t care. “I don’t think,” wrote Roy Strong after first meeting him, “that I’d ever before encountered anyone so overtly homosexual.”6

Among the young, however, whose attitudes to sex were becoming more liberal, tolerance was generally more widespread, as it was among the upper echelons of society where it was often openly tolerated and defended. Indeed, it was the House of Lords which first declared in favour of reform, when in October 1965 it passed the Sexual Offences Bill, introduced by the Liberal peer the Earl of Arran, though not without some opposition from peers like Lord Dilhorne, who thundered that such a bill would not only legalise sodomy, but encourage male prostitution. It was a brave move on Arran’s part, who, like many social reformers before him, was to be the victim of abuse, contempt and ridicule. The bill suffered a stormier ride through the Commons, steered by the maverick Labour MP Leo Abse, and it was to be nearly two years before it passed on to the statute books.

It was against this background that Hockney began work on his next project, a series of etchings based on the work of Constantine Cavafy, whose poems had previously inspired several paintings—Waiting for the Barbarians, Kaisarion with All His Beauty and Mirror, Mirror on the Wall. Ever since his Egypt trip in 1963, Hockney had harboured a secret desire to illustrate a series of Cavafy’s poems, an ambition he mentioned to Paul Cornwall-Jones, who immediately encouraged him to go ahead. Discovering that Cavafy’s translator, John Mavrogordato, was still alive and living in London, Hockney went to visit him in Montpelier Walk, behind Harrods. A pacifist, like Hockney, he was described as “a generous, courteous, charming, and modest man … a philanthropist, genial companion, conversationalist, connoisseur, talented amateur artist … and collector of books and art.”7 It was a fruitless trip, however, because by the time of the visit the former professor of Byzantine and Modern Greek Language and Literature at Oxford was eighty-four years old, suffering from dementia and had completely lost his memory.

When Hockney recounted this tale to Stephen Spender, asking for his advice, he introduced him to a young Greek poet called Nikos Stangos, and it was decided that the two of them should provide a new translation of the poems to go with Hockney’s drawings. A year younger than Hockney, Stangos had studied philosophy at Harvard University and was working as a press officer at the Greek Embassy in London; as a fellow homosexual who shared Hockney’s socialist principles, and who spoke perfect English, he was the perfect collaborator.

On his Egypt trip in 1963, Hockney had visited Alexandria, the home city of Cavafy, who had lived in a second-floor apartment above a brothel in the Rue Lepsius. From the balcony Cavafy could see both a hospital and the Church of St. Saba, which had prompted him to comment, “Where could I live better? Below, the brothel caters for the flesh. And there is the church which forgives sin. And there is the hospital where we die.”8 Hockney’s mind had been alive with the descriptions he had read of Alexandria in Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet, but instead of the bustling cosmopolitan and bohemian city of his imagination, where generations of immigrants from Greece, Italy and the Levant had settled to take advantage of its position as a centre of commerce, he found a dull modern port almost totally devoid of any Europeans. Realising that he would get no inspiration there, he decided instead to travel to Beirut, then considered the Paris of the Middle East. “I didn’t know anybody there,” Hockney remembers, “but I thought I’d just go there to get atmosphere. I went for about a week. I carried a sketchbook wherever I went, drawing the buildings, the Arabic signs and exploring the seedy parts. It was a good destination then, a stopover if you were heading to the east, and a very cosmopolitan city, much more cosmopolitan than Cairo or Alexandria, and it also had a reputation for being rather racy.”9 On his return he called his mother to tell her about it. “David phoned in the evening,” she wrote in her diary. “He has had a marvellous time as usual and done a lot of work. Visited Damascus and Lebanon. Lucky boy! How wonderful.”10

Cavafy’s poems can be divided into two categories: the poems about historical Alexandria and mythology, and the sensual poems set in modern Alexandria, lyrical musings on love and eroticism, mostly concerned with furtive and often doomed love between young boys. “I suppose that because I know more about love than about history, I chose to do those,” says Hockney. “Of course they are about gay love, and I was quite boldly using that subject then. I was aware that it was illegal, but I didn’t really think much about that at the time. I was living in a bohemian world, where we just did what we pleased. I wasn’t speaking for anybody else. I was defending my way of living.”11 In creating the illustrations for the book, Hockney worked from three sources: his own drawings, photographs which he had either taken or bought, and drawings which he etched straight onto the plate from life. Two Boys Aged 23 or 24, for example, is based on a photograph of Mo McDermott and Dale Chisman lying in bed, while According to the Prescriptions of Ancient Magicians was copied onto the plate from Boys in Bed, Beirut, an ink drawing made in London using two more friends as models.

The etchings made for Illustrations for Fourteen Poems from C. P. Cavafy, rather than being exact illustrations of the contents of each poem, were largely intended to parallel them, suggesting to the reader an experience similar to that described. Whereas Cavafy’s young men were often tormented and fugitive, David’s had a defiance about them, a feeling of indifference to what the world might think. As they climb into bed and prepare to make love they look the viewer straight in the eye. With “his etchings for the Cavafy poems,” wrote his contemporary Derek Jarman, “he produced vital new images that pulled away the veil behind which the work of older painters had had to hide. The Cavafy etchings were particularly powerful. With his fine line he produced images of boys in bed that resembled Cocteau—but without a trace of the sentimentality which so often bedevils gay art.”12

In October 2010, Neil McGregor, the director of the British Museum, included in his radio series A History of the World in a Hundred Objects the Hockney etching In the Dull Village as an example of art as propaganda. The figures, he commented, “could be American or British, but they inhabit the world of the poem, which is about a young man trapped by his circumstances, and who escapes his dreary surroundings by dreaming of the perfect love partner … a boy imagined rather than actually present in the longed-for flesh. Cavafy’s poem reads as modern verse, but looks back to an ancient Greek world in which love between men was an accepted part of life. They are poems of longing and loss, of the first meetings of future loves, and of intoxicating passionate encounters and they were exciting fodder for Hockney, material that he could use for his own art as an example of how an artist could make a public statement out of such private experience.”13

in the boring village where he’s waiting out the time–

he goes to bed tonight full of sexual longing,

all his youth on fire with the body’s passion,

his lovely youth given over to a fine intensity.

And in his sleep pleasure comes to him;

in his sleep he sees and has the figure, the flesh he longed for…

Hockney took a deliberately realistic approach in making these etchings, which he felt suited the subject matter, and they were among his first ventures into line drawing with ink, an enterprise whose sheer difficulty excited him. “I never talk when I’m drawing a person,” he wrote, “especially if I’m making line drawings. I prefer for there to be no noise at all so I can concentrate more. You can’t make a line too slowly, you have to go at a certain speed; so the concentration needed is quite strong. It’s very tiring as well. If you make two or three line drawings, it’s very tiring in the head, because you have to do it all at one go, something you’ve no need to do with pencil drawing … you can stop, you can rub out. With line drawings you don’t want to do that. You can’t rub out line, mustn’t do it. It’s exciting doing it, and I think it’s harder than anything else; so when they succeed they’re much better drawings, often.”14 Unlike his previous etchings, which relied much more on the use of aquatint, the Cavafy illustrations are almost entirely line drawings and they are undoubtedly one of his greatest achievements. “I have just seen the first pulls from some of the plates,” wrote Edward Lucie-Smith in The Times, “and thought them not only the best work I have seen by the artist, but probably the finest prints seen in England since the war.”15

Alecto Editions was by now operating out of premises in Kelso Place, South Kensington, which was large enough to incorporate the entire production process. Along with Mike Rand, an assistant in the etching studio at the Royal College, they took on Maurice Payne, with whom Rand had studied at Ealing Art School. Payne was young and eager to learn and, equally important, took to Hockney and his coterie from the very start. “It was a fun and interesting time,” he recalls. “What interested me in meeting this gay crowd was that people could be so different. Personally I found straight guys boring to be with because it was all about who’s got the girls and who hasn’t, that whole competitive thing. When I was at school I was very good at sports and football and things like that, and I remember when I met Mo and Ossie the first time, there was an occasion when they were crying together about something, and I remember thinking, ‘Straight guys would never show any emotion. Great, it’s OK to cry.’ ”16 Payne was to be David’s assistant on the Cavafy project and for many years to come.

Since Hockney was already a skilled printer himself, most of the initial work was done at Powis Terrace. This consisted of preparing the copperplates by covering them with a film of wax, drawing onto them with a sharp steel-tipped “pen,” and the actual etching process itself, in which the completed plate is placed in a bath of acid, mixed with potassium chlorate to speed up the process. Because the acid bath produced such strong unpleasant fumes, this procedure took place on the balcony where most of the vapours would blow away into the street. It proved impossible to eradicate all traces of the stink, however. “The fumes creep everywhere,” Hockney told James Scott, who was making a film about the Cavafy etchings for the Arts Council, “and I couldn’t sleep so well because of them, so I had to keep getting up early and keep working on them. That was very good really.”17 When the plate had been in the bath long enough, it was then washed under the shower until all traces of the acid were washed away. Once the plates were cleaned up and polished they were ready to be taken over to Kelso Place to be pressed in one of their huge cast-iron printing presses.

At the same time that he was working on these etchings and beginning to develop a more naturalistic way of realising the human figure, Hockney was approached by the actor Iain Cuthbertson, an associate director of the Royal Court Theatre, to design a play which he was about to direct. The suggestion had come from the artistic director of the Royal Court, Bill Gaskill, a founding director of the National Theatre and a fellow Yorkshireman, born in Shipley. “I had never done anything in the theatre,” Hockney recalls, “but I was consciously interested, and had seen a lot of theatre in the early sixties. I remember seeing Waiting for Godot, and stage versions of Under Milk Wood, and Mo knew the theatre and he might get us tickets for things. I didn’t know the play but I was sympathetic to it immediately.”

The play was Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, one of the first works of the Theatre of the Absurd, which at its premiere in Paris in 1896 had so offended the audience with what they saw as its vulgar and obscene nature that they almost rioted. The version that was to play at the Royal Court had been translated by Cuthbertson and was to be co-directed by him and Gaskill. It was the first time it had ever been performed in England, and it was to be presented as a comedy, with the lead being taken by the great music-hall star Max Wall.

Initially Hockney was resistant to the idea. “After all,” he said, “in paintings before that, I had been interested in what you might call theatrical devices, and I thought that in the theatre, the home of theatrical devices, they’d be different, they wouldn’t have quite the same meaning as they do in painting, they wouldn’t be contradictory—a theatrical device in the theatre is what you’d expect to find.”18

Fear of failure, however, was not something that was ever to loom large in Hockney’s life, and his eventual decision to take on the project was indicative of a lifelong willingness to try out new mediums. He was attracted by the surreal humour of the play, by the way the action raced along, but most of all by the written instructions of the playwright to eschew traditional scenery. “I designed it based on Alfred Jarry saying ‘Don’t bother with the scenery,’ ” he recalls, “ ‘just put a notice up saying Parade Ground.’ So I took that up and for the Parade Ground people just walked on with a letter in their hands, and put it down and when they walked off it just read Parade Ground, and things like that.” The Polish Army was represented by two people with a banner tied round them, which simply read “Polish Army.”

In the end Hockney had a lot of fun working on Ubu Roi, designing both the sets and the costumes, which were painted on sandwich boards and carried around by the actors. Jack Shepherd, as Mère Ubu, had bosoms sewn onto the outside of his dress, with red nipples which lit up, while Max Wall wore a pear-shaped body suit and sported a green bowler hat. “My own first entrance in the play,” Wall reminisced, “was made from beneath the stage as I was hauled up to stage level on a lift while sitting on a toilet that matched up with the backdrop on which was painted a cistern and lavatory chain.”19 The sets themselves were like large paintings, a garish series of poster-paint backdrops, suspended from the flies by ropes, which dropped down when required, “like a joke toy theatre” as Hockney remembered it. “Hockney’s hair was bleached,” wrote Bill Gaskill in his memoirs, “and with his huge glasses and not dissimilar features he looked like the ghost of George Devine as he peered from the back of the circle at the re-creation of his brushstrokes on the backcloth. ‘I didn’t think they’d copy it exactly.’ ”20

Polish Army from Ubu Roi, 1966 (illustration credit 7.2)

In June 1966, as soon as his work on Ubu was completed, Hockney set off for California, where he had been asked to teach for six months at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He left England with one major worry on his mind: his father’s health. Kenneth had been diagnosed with diabetes three years previously and had twice recently gone into diabetic comas—a problem of his own making, as he had stopped taking the pills that had been prescribed for his mild form of the disease. This led to him being taken into hospital just before Christmas, where, refusing even to contemplate taking insulin, he was put back on his tablets and after two weeks spent as a “difficult” and “aggressive” patient, signed himself out of the hospital against the opinion of five doctors.

“Kenneth is very confident he can cure himself,” wrote Laura on 17 January 1966, “and is taking tablets regularly.” But ten days later, he began to deteriorate again, mulishly refusing, day after day, to see a doctor. “And so it went on,” wrote Laura in despair, “he getting worse and worse—yet fighting against it with all his might—so sure he could cure himself right up to Sunday morning when he had to give in.” He “gave in” only because he had fallen into a coma, and had to be rushed to hospital where they eventually managed to bring him round. Within a fortnight, however, he was in a coma again, this time for twenty-four hours, an event that finally left him in no doubt that he had to follow doctor’s orders. On 10 February, Laura was able to observe: “Now getting proud of the fact that he can inject himself—a good sign he is better.”21

In New York, meanwhile, Hockney picked up his new car, an open-topped Triumph which had been shipped over from England, and drove it across America to California, fantasising all the way about his forthcoming job. “… as I got further and further West,” he wrote, “I became more and more excited, imagining my class would be full of young blond surfers.”22 When he finally arrived in LA, he went to stay in a small apartment in Larabee Drive, off Sunset Boulevard, belonging to a young dealer, Nick Wilder, whom Hockney had met the previous year.

Openly gay when he first set up shop on La Cienega, the 28-year-old Wilder stood out from the rest of the leather-jacketed, macho art types because of his preppy appearance. “He seemed like a Yale man in a suit,” Jack Larson recalls, “very proper and reserved, but he wasn’t like that at all.”23 The youngest of three children of a scientist who had been one of the inventors of Kodachrome, Wilder had attended Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he got himself a job at the university museum as projectionist for art history slide lectures, and had graduated at Stanford in art history. Bitten, like so many of his contemporaries, by the California bug, he had opened his gallery on La Cienega after establishing a reputation as a wunderkind dealer at the Lanyon Gallery in Palo Alto, which was regarded as the leading Bay Area gallery. Rumours were soon flying around that he was heir to the Kodak film fortune and had bottomless funds to support and promote artists. “In fact, I started the gallery by leaping in, in this naive, monomaniacal, underfunded way,” Wilder recalled. “I often didn’t know where the rent was coming from. I didn’t have enough money but people thought I was rich because of the way I looked.”24

Hockney and Wilder shared a passion both for art and the bohemian way of life. “Nick was about my age, quite intellectual,” Hockney recalls, “and I instantly got on with him. He was only just opening his gallery, where he showed very radical artists for the time. He was a bit disorganised, but very driven, and he loved the arts and the artists.”25 Wilder was to discover many great, then unknown, local talents, like Ron Davis, Bruce Nauman, Robert Graham and Tom Holland, and the Nicholas Wilder Gallery soon flourished, with a number of big-name East Coast painters like Kenneth Noland, Helen Frankenthaler, Cy Twombly, Jules Olitsky and Barnett Newman eventually joining. Despite Wilder’s conventional appearance, he remained an out-and-out bohemian, the large living room at his West Hollywood apartment furnished solely with a huge yellow sculpture by John McCracken that was often draped with his underwear. “The tiny kitchen,” Hockney remembers, “contained a refrigerator which never had anything in it other than pickles and sauces because if we wanted food, we would just call up Chicken Delight and somebody would deliver chicken or pizza or stuff like that. There were just mattresses on the floor for sleeping, and you would have gone to bed and some boy would come in and get on the mattress with you. It was a life that we liked. You never knew what was going to happen any night and I thought it was terrific. I was young and free and this is what we all did.”26

The class at UCLA to which Hockney had been assigned turned out to be a disappointment, because far from being full of the young blond surfers, it was, just like in Iowa, peopled with would-be teachers who were there solely to get credits that would give them better pay. There were not even any keen students of art whom it might have been a pleasure to teach. Then, just as he was beginning to despair, in walked a young student who was to be one of the great passions of Hockney’s life, Peter Schlesinger. “I took one look at him,” Hockney remembers, “and I thought, ‘That looks like a real young Californian.’ He was just the kind of person I’d been hoping to meet in my class.”27

Schlesinger was the eighteen-year-old son of a life-insurance salesman, the second of three brothers from the San Fernando Valley, better known to Angelenos as “the Valley.” The family had moved when he was ten to Encino, a small town which lies on the northern slopes of the Santa Monica Mountains, where they lived an ordinary middle-class life, and the boys had a liberal Jewish upbringing. From the age of seven or eight, Schlesinger had known that he wanted to be an artist, an ambition in which he was encouraged by his parents, and every Saturday during his high-school years, his father used to drive him all the way to UCLA to take art courses. In 1965, a dreamy time when the hippy movement was just beginning, he was enrolled at the University of California in Santa Cruz. It had no art classes, however, so in the summer of 1966 he came back down to live with his parents and take a drawing course at UCLA. “On the first day of class,” he recalled, “the professor walked in—he was a bleached blond; wearing a tomato-red suit, a green and white polka-dot tie with a matching hat, and round black cartoon glasses; and speaking with a Yorkshire accent. At that time, David Hockney was only beginning to become established in England, and I had never heard of him.”28

It could be said that fate threw them together, since it later turned out that Schlesinger shouldn’t have been in the Hockney class, which was for advanced students only. Hockney, however, assured the faculty that in his opinion Schlesinger was quite advanced and showed considerable talent, and so he was allowed to keep him. “I could genuinely see he had talent,” says Hockney, “and on top of that he was a marvellous-looking young man. I was always looking for lively young people and he was intelligent and he was curious, and a far cry from Bobby Earles.”29 Schlesinger was equally taken with Hockney. “I was drawn to him because he was different,” he remembers. “He was teaching life drawing. He was a good teacher who loved teaching and giving his opinion. He was also fun and lively and amusing and I was quite shy in those days and I liked hanging out with older people rather than my own age group.”30

Peter Schlesinger and David Hockney (illustration credit 7.3)

It wasn’t long before Schlesinger was spending all his spare time away from class with Hockney, who couldn’t wait to introduce him to his friends. “One day David came by,” Jack Larson recalls, “and he brought this young student, Peter. He was very sweet, and quite observant, but I suppose he was very innocent. We all went out to dinner, and there was no doubt in my mind that David was absolutely smitten with this wonderful-looking, quite charming young boy who wasn’t a Beverly Hills swinger, but a boy from the Valley.”31 That Hockney was in love was equally clear to Don Bachardy, who recalls that “it was clear right away that there was something going on between them.”32

Owing to Schlesinger’s shy nature and an innocence about his sexuality, what was actually going on at this stage was nothing physical, merely the gradual process of them falling in love. “I didn’t really consider whether or not I was gay at that time,” says Schlesinger, “because I guess I didn’t really know what it was. I didn’t identify it till I actually did it. We just hung out together and nothing else happened for two or three months.”

Schlesinger was still living with his parents, and he waited till they were away for a weekend before asking Hockney over to the house. They spent the day by the pool, where he did some drawings of Schlesinger sitting in a deckchair in his swimming trunks reading a book. The moment that the affair was finally consummated took place just before the end of term, when Schlesinger was faced with having to return to Santa Cruz and the realisation that this would take him away from David, who had to stay in LA. For David, to have finally found a soulmate was the realisation of a dream. “It was incredible to me,” he later told the art historian Marco Livingstone, “to meet in California a young, very sexy, attractive boy who was also curious and intelligent. In California you can meet curious and intelligent people, but generally they’re not the sexy boy of your fantasy as well. To me this was incredible.”33

When the term was over, Hockney flew to London for a few days, courtesy of the Royal Court, to attend the opening of Ubu Roi on 21 July. Unable to find the time to get to Bradford, he persuaded his parents to come to London to see the play. “Ken and I … went to the Royal Theatre to see the play,” wrote Laura in her diary. “Not quite our cup of tea—tho’ we knew what to expect.”34 Critically, too, the show had a lukewarm reception, the main gripe being that in choosing to present it as “something between a Christmas pantomime and an exhibition of child’s art,”35 Iain Cuthbertson had deprived the play of its main virtue, which was to outrage the public. Max Wall was criticised for simply playing himself. “Ubu may be an international figure,” wrote the drama critic of The Times, “but wherever he goes and however he changes his appearance, he must remain unmistakably a monster … Of this there is not a trace in Mr. Wall’s performance.”36 It was generally agreed that “visually, at any rate, it is great fun,”37 though Hockney was not asked to do theatre design again for about ten years, leading him to assume that he was simply no good at it; the Ubu sets represented a last gasp for his working in a highly stylised and artificial manner.

To tie in with the Royal Court opening, Kasmin put on a show of the original drawings for the sets and costumes, described by Paul Overy in the Listener as being “gay, witty and lightweight.”38 He combined it with the first exhibition of the Cavafy etchings, which certain people found perplexing. Hockney was in the gallery one day when two old ladies came in, and they asked him to explain to them why two men were sitting on the bed in the same room. “The thing is,” Hockney replied mischievously, “they are very hard up and they have to share a room.” The Cavafys were generally admired, although, given the subject matter, they were slow to sell, but, as Overy pointed out, “Hockney concentrates on presenting homosexual liaisons as something completely normal and acceptable. To do this requires a courage one must admire …”39 It was to be Hockney’s last show with Kasmin for a while, because when he flew back to California at the end of the month he was not to return to England for a whole year.